Abstract

We were impressed by the similarity and complementarity between experimental results concerning neurotoxicity induced by prefibrillar oligomers (PFOs) of two different proteins belonging to the “amyloid” family: salmon Calcitonin (sCT) and Amyloid-β1-42 (Aβ1-42). The results were recently published by our group for sCT [1] and by Yasumoto’s group for Aβ1-42 [2]. The comparison is very interesting in the open debate about the intriguing hypothesis of the existence of a “common mechanism” in the pathogenesis of amyloid neurodegenerations. Here we wrote a comment to analyze in detail this parallelism and to suggest a possible interpretation. Briefly, the existence of a “common hydrophobic profile” in the central parts of the primary sequences of the two proteins could lead to the formation of metastable PFOs characterized by a “common hydrophobic outfit” able to damage neurons via a “unified mechanism” we proposed for sCT where “membrane permeabilization” and “receptor-mediated” paradigms coexist.

Keywords

Amyloid neurotoxicity, Amyloid oligomers, Protein aggregation, Salmon calcitonin, β-amyloid

Introduction

Protein misfolding is a common feature in several highly diffused (Alzheimer’s (AD) and Parkinson’s (PD)) or rare (Creutzfeldt–Jacob’s (CJD) or Niemann–Pick’s (NP)) human severe amyloid-related neurodegenerations and results in the formation and deposition of amyloid aggregates [3-6]. The amyloid superfamily is a crowded house, which includes well-known proteins, like Amyloid-b1-42 (Aβ1-42), a-Synuclein (aS), and Prion-Protein (PrP) implicated in AD, PD, and CJD, respectively as well as hormones such as Insulin or Calcitonin (CT) [7]. The exact molecular mechanisms at the base of the amyloid neurotoxicity are still unknown even though the existence of “common mechanisms” focused on low molecular weight Prefibrillar Oligomers (PFOs) and not on Mature Fibers (MFs) or monomers, have been proposed [8,9].

Major efforts have been made to clarify the link between oligomer structures and neurotoxicity, based on the analysis of their effects in vitro [10-12] (neuronal cultures and acute brain slices [13] and in vivo (direct administration in the brain [14,15]. However, the culprit has not yet been identified. As Benilova et al. [16] point out, this can be due to the intrinsic metastability of the aggregates leading to difficulties in the comparison of results from different research groups. However, there is a general agreement that small and soluble PFOs are toxic species [7].

Salmon Calcitonin (sCT) - a 32 amino acid polypeptide hormone used in the treatment of osteoporosis - is neurotoxic in vitro and forms amyloid aggregates at a very low rate [17]. Thanks to this characteristic, we successfully investigated the effects of native sCT-PFOs from the early stages, avoiding any fixing procedure [10,18]. We recently demonstrated that sCT-PFOs, but not MFs, induced abnormal permeability to Ca2+, reduced cellular viability, and impaired Long-Term Potentiation (LTP) and expression of Post-Synaptic Density (PSD-95) protein and pre-synaptic protein Synaptophysin. In our paper, we proposed that the two pre-existing neurotoxicity paradigms used to explain amyloid neurotoxicity, “membrane-permeabilization” and “receptor-mediation”, could not separately explain our data but must coexist, constituting a novel “unified neurotoxicity mechanism” [1].

We recently noticed the paper published by Yasumoto et al. in “The FASEB Journal” concerning High Molecular Weight-Aβ1-42 (HMW-Aβ1-42) and Low Molecular Weight-Aβ1-42 (LMW-Aβ1-42) oligomers inducing neurotoxicity via plasma membrane damage [2]. This paper follows other important papers published by the Ono’s and Teplow’s group in this field, as an example see [19,20].

Interestingly, using a different protein (Aβ1-42), they obtained experimental results very similar to our findings relative to sCT.

There are some issues we would like to address here:

1. Yasumoto’s and our samples can be matched: HMW-Aβ1-42 corresponds to sCT-PFOs.

Yasumoto et al. [2] clearly stated that the HMW-Aβ1-42 sample spans from trimers to Proto Fibrils (PFs), including tetramers, pentamers, and hexamers. We showed exactly the same in our paper for sCT-PFOs. Moreover, Yasumoto’s results concerning the Ca2+-influx (figure 5) and LTP (figure 7) alterations due to HMW-Aβ1-42 sample are very similar to our results obtained by sCT-PFOs (figure 2 and figure 5);

2. The two Yasumoto’s HMW-Aβ1-42 and LMW-Aβ1-42 samples are of the same kind.

This can be deduced from the small difference in the oligomer mean diameters (figure 1F) and by the similar biological effects they induced;

3. Yasumoto didn’t show results concerning Aβ1-42 monomers. This was likely due to the well-known high aggregation rate of Aβ1-42. We presume that Yasumoto et al. didn’t have an actual monomeric sample while the very slow aggregation rate of sCT allowed us to overcome this problem;

4. In both papers, the neuronal membrane disruption was indicated as the trigger event for neurotoxicity. In the title and in figure 8 Yasumoto et al. indicated “neuronal membrane disruption” as the main cause “..of Ab oligomer-induced neuronal injury and death”. This is the same conclusion of our paper dealing with sCT.

5. In both papers, blocking NMDA receptors abolished the neurotoxicity.

In this paper, concerning sCT, we proposed that the triggering event activating a “unified neurotoxicity mechanism” was the membrane permeabilization exerted by PFOs. Amyloid-pores, unable “per se” to heavily raise the intracellular Ca concentration, were capable of triggering “receptor-mediated” excitotoxicity. We based this conclusion on the protective effect obtained by blocking the NMDA receptors by MK-801 [1]. Notably, Yasumoto et al. reported the same result for Aβ1-42 by blocking NMDA receptors by Memantine (figure 5B) [2].

Here we speculate about the surprising similarity and complementarity of our and Yasumoto’s results.

Concerning oligomers, we noticed that our findings relative to sCT-PFOs were very similar (see item 1) to Yasumoto’s results relative to Aβ1-42, LMW, and HMW oligomers (see item 2).

Concerning monomers, we showed in our paper that sCT monomers were unable to activate the proposed “unified neurotoxicity mechanism” [1]. Despite Yasumoto et al. didn’t show results relative to monomers (see item 3), it is known that purified Aβ1-42 monomers are protective and non-toxic [21] and unable to produce “amyloid-pores” in an excised patch of membranes [22].

Based on these considerations, we think that the “unified neurotoxicity mechanism” we proposed for sCT [1] can also be applied to interpret Yasumoto‘s results relative to Aβ1-42.

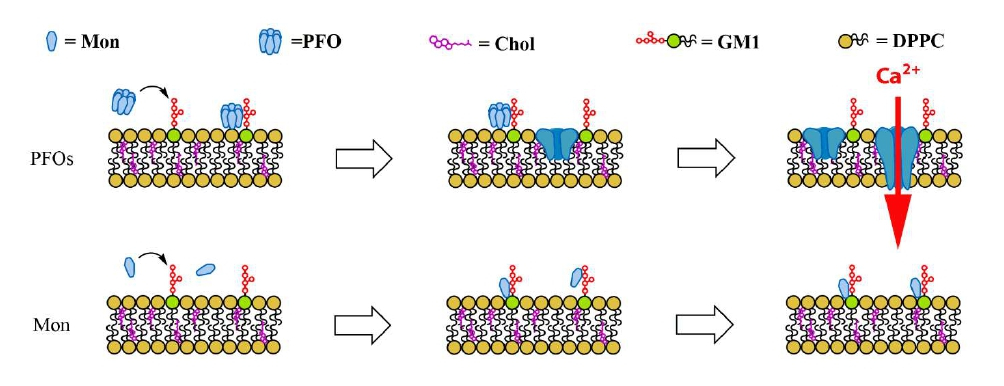

More in particular, in both cases, the triggering event could be the formation of “amyloid-pores” described in the literature for both proteins [22,23]. In a recent paper, we described in detail this mechanism in the case of sCT-PFOs [18]. As summarized in figure 1, after the interaction with particular membrane structures rich in charged lipids as GM1-monosialogangliosides, named “lipid-rafts”, sCT-PFOs were incorporated in the lipid bilayer and formed channels able to permeabilize the neuron membrane. Conversely, monomers interacted with the same structures but, remaining outside the membranes, didn’t affect the ionic permeability (Figure1).

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the interaction of amyloid Pre-Fibrillar-Oligomers (PFOs) or Monomers (Mon) with neuron membranes, rich in charged lipids as GM1-monosialogangliosides. The formation of the “amyloid-pore” is the trigger for the Ca2+ homeostasis unbalance [1].

However, this phenomenon is only the trigger for the Ca2+ homeostasis unbalance and is not able “per se” to damage neurons without the involvement of the MNDA-receptors. This is demonstrated by the inhibition of the Ca2+-influx achieved by MK-801 for sCT [1] and Memantine for Aβ1-42 [2].

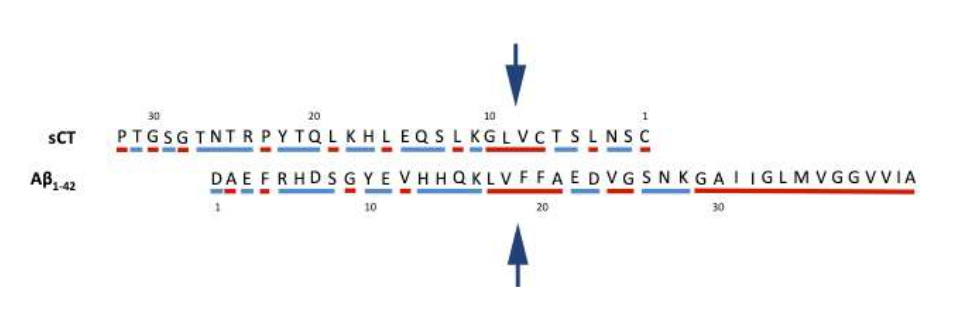

Thus, we wonder how it was possible to obtain such comparable results with such different proteins. We speculate that some common features in the hydrophobic profiles of the two proteins could be the structural basis for the assembly of PFOs with a similar hydrophobic “outfit”. We can see in Figure 2 that the two peptides are similar in dimension (32 and 42 residues) and that the reversed sequence of sCT and the normal sequence of Aβ1-42, show a core (highlighted by arrows) of about five highly hydrophobic residues (red) enclosed within mixed hydrophobic and polar segments (blue). Notably, the reversed sequence of sCT looks like to the specific segment of Aβ1-42 exposed to the medium. Consider that the last set of ten hydrophobic C-terminus residues of Aβ1-42, tend to be excluded by the medium while the remaining part tends to be exposed.

Figure 2: Reversed sCT (top) and normal Aβ1-42 (bottom) sequences, shifted of 6 residues. Hydrophobic (red) and polar/charged (blue) residues are highlighted. Arrows indicate the common hydrophobic central part.

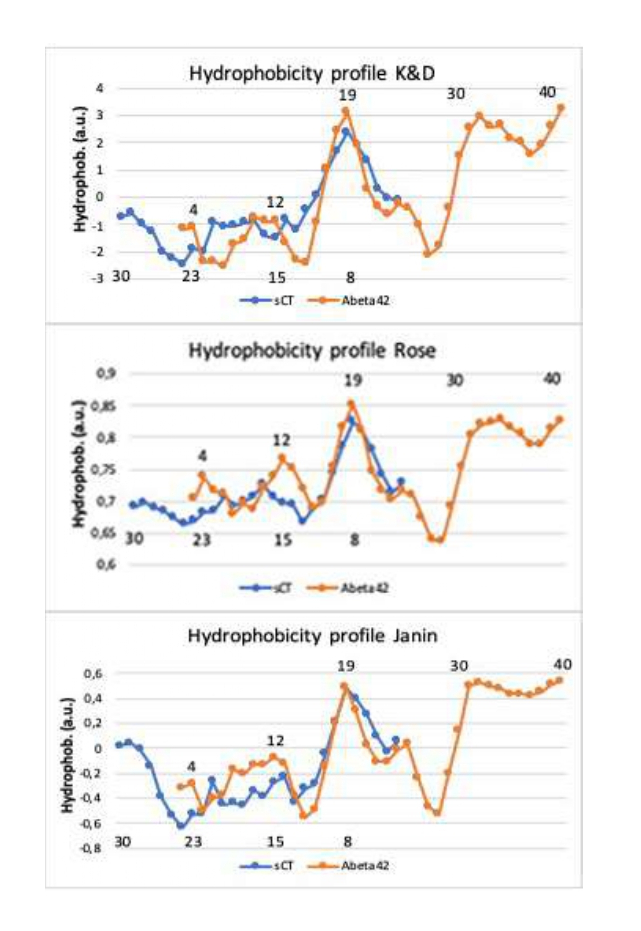

To better investigate the similarity in the sequences highlighted in figure 2, we simulated the hydrophobic profiles by means of three hydrophobicity scales. In particular, the hydrophobic value of the single amino acid residue is linearly averaged with respect to the ±2 nearest residues (window size of 5 with a weight of 50% at the edge). The results are reported in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Hydrophobic profiles of the reversed sequence of sCT and the normal sequence of Aβ1-42, shifted of 6 residues, obtained by three different hydrophobic scales: Kyte & Doolittle’s, Rose’s and Janin’s scale. Numbers above and below indicate the aminoacid positions in the sCT and Aβ1-42 primary sequences.

In the Kyte & Doolittle’s (K&D) scale [24] the hydrophobic character is derived from the physicochemical properties of the amino acid side chains and results mainly from the inspection of the amino acid structures. In the Rose’s [25] and Janin’s [26] scales, starting from the protein 3-D structures, the hydrophobic character is defined as the tendency for a residue to be found inside of a protein rather than on its surface.

Notably, the hydrophobic profiles of the two proteins, obtained using all scales after a shift of 6 residues, showed a “common profile” in the central part.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our idea is that this “common hydrophobic core” leads, under similar chemical-physical conditions, to a “common PFOs structure” characterized by a common hydrophobic/polar “outfit” able to activate the “unified neurotoxicity mechanism”, described for sCT [1]. Moreover, in our opinion, the fast aggregation of Aβ1-42, concerning the slow sCT could be due to the long hydrophobic tail of Aβ1-42 missing in the sCT (see figure 2). The hydrophobic force occurring between the tails of the Aβ1-42 constituting the aggregate would at the basis of the faster formation of the β-sheet configuration in the core of PFOs and eventually in the MFs.

The research into the existence of this “common outfit” in the amyloid family, performed by molecular dynamics simulations combined with biophysical techniques, would be very useful to elucidate this outstanding similarity and to design innovative strategies to counteract the adverse effects exerted on cellular membranes at the basis of such important diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Italian “Ministero della Salute” with the “Progetto Ordinario di Ricerca Finalizzata (RF-2013-02355682)” entitled: “Calcitonin oligomers as a model to study the amyloid neurotoxicity: the focal role played by lipid rafts in the prevention and cure”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

2. Yasumoto T, Takamura Y, Tsuji M, Watanabe‐Nakayama T, Imamura K, Inoue H, Nakamura S, et al. High molecular weight amyloid β1‐42 oligomers induce neurotoxicity via plasma membrane damage. The FASEB Journal. 2019 Aug; 33(8):9220-34.

3. Dobson CM. Protein misfolding, evolution and disease. Trends in biochemical sciences. 1999 Sep 1; 24(9):329-32.

4. Dobson CM. Protein folding and misfolding. Nature. 2003 Dec; 426(6968):884-90.

5. Schnabel J. Protein folding: The dark side of proteins. Nature. 2010; 464:828–829.

6. Dobson CM. Principles of protein folding, misfolding and aggregation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2004.

7. Chiti F, Dobson CM. Protein misfolding, amyloid formation, and human disease: a summary of progress over the last decade. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2017 Jun 20; 86:27-68.

8. Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, et al. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003 Apr 18; 300(5618):486-9.

9. Glabe CG. Common mechanisms of amyloid oligomer pathogenesis in degenerative disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2006 Apr 1; 27(4):570-5.

10. Diociaiuti M, Macchia G, Paradisi S, Frank C, Camerini S, Chistolini P, et al. Native metastable prefibrillar oligomers are the most neurotoxic species among amyloid aggregates. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease. 2014 Sep 1; 1842(9):1622-9.

11. Pellistri F, Bucciantini M, Relini A, Nosi D, Gliozzi A, Robello M, et al. Nonspecific interaction of prefibrillar amyloid aggregates with glutamatergic receptors results in Ca2+ increase in primary neuronal cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008 Oct 31; 283(44):29950-60.

12. Kritis AA, Stamoula EG, Paniskaki KA, Vavilis TD. Researching glutamate–induced cytotoxicity in different cell lines: a comparative/collective analysis/study. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2015 Mar 17; 9:91.

13. Lee MC, Yu WC, Shih YH, Chen CY, Guo ZH, Huang SJ, Chan JC, Chen YR. Zinc ion rapidly induces toxic, off-pathway amyloid-β oligomers distinct from amyloid-β derived diffusible ligands in Alzheimer’s disease. Scientific Reports. 2018 Mar 19; 8(1):1-6.

14. Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002 Apr; 416(6880):535-9.

15. Hong S, Ostaszewski BL, Yang T, O’Malley TT, Jin M, Yanagisawa K, Li S, Bartels T, Selkoe DJ. Soluble Aβ oligomers are rapidly sequestered from brain ISF in vivo and bind GM1 ganglioside on cellular membranes. Neuron. 2014 Apr 16; 82(2):308-19.

16. Benilova I, Karran E, De Strooper B. The toxic Aβ oligomer and Alzheimer's disease: an emperor in need of clothes. Nature Neuroscience. 2012 Mar; 15(3):349-57.

17. Diociaiuti M, Gaudiano MC, Malchiodi-Albedi F. The slowly aggregating salmon Calcitonin: a useful tool for the study of the amyloid oligomers structure and activity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2011 Dec; 12(12):9277-95.

18. Diociaiuti M, Bombelli C, Zanetti-Polzi L, Belfiore M, Fioravanti R, Macchia G, et al. The Interaction between Amyloid Prefibrillar Oligomers of Salmon Calcitonin and a Lipid-Raft Model: Molecular Mechanisms Leading to Membrane Damage, Ca2+-Influx and Neurotoxicity. Biomolecules. 2020 Jan; 10(1):58.

19. Ono K, Condron MM, Teplow DB. Structure–neurotoxicity relationships of amyloid β-protein oligomers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009 Sep 1; 106(35):14745-50.

20. Ono K. Alzheimer's disease as oligomeropathy. Neurochemistry International. 2018 Oct 1; 119:57-70.

21. Hoffman KB, Kessler M, Lynch G. Sialic acid residues indirectly modulate the binding properties of AMPA-type glutamate receptors. Brain Research. 1997 Apr 11; 753(2):309-14.

22. Bode DC, Baker MD, Viles JH. Ion channel formation by amyloid-β42 oligomers but not amyloid-β40 in cellular membranes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2017 Jan 27; 292(4):1404-13.

23. Diociaiuti M, Polzi LZ, Valvo L, Malchiodi-Albedi F, Bombelli C, Gaudiano MC. Calcitonin forms oligomeric pore-like structures in lipid membranes. Biophysical Journal. 2006 Sep 15; 91(6):2275-81.

24. Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1982 May 5; 157(1):105-32.

25. Rose GD, Geselowitz AR, Lesser GJ, Lee RH, Zehfus MH. Hydrophobicity of amino acid residues in globular proteins. Science. 1985 Aug 30; 229(4716):834-8.

26. Janin JO. Surface and inside volumes in globular proteins. Nature. 1979 Feb; 277(5696):491-2.