Abstract

CAR-T cell therapy revolutionized the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell hematologic malignancies, substantially altering their prognosis. Alongside its remarkable efficacy, however, this approach is frequently accompanied by treatment-related toxicities. While cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) are the best characterized and usually manageable with standard interventions, a spectrum of additional, non-canonical complications has gained increasing clinical recognition. These include persistent cytopenias (immune effector cell–associated hematologic toxicity, ICAHT), immune effector cell–associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis–like syndrome (IEC-HS), and coagulopathies. Such events may manifest late, persist for prolonged periods, and significantly compromise patients’ quality of life. In this manuscript, we summarize current evidence and guideline-based recommendations regarding these non-canonical complications, with the aim of providing clinicians a practical framework for their recognition, management, and integration into routine post-infusion care.

Keywords

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell, Cytokine release syndrome, Immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity, Non-canonical toxicity, Immune effector cell -associated hematologic toxicity, Immune effector cell -associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis- like syndrome, Coagulopathy

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy has markedly improved the prognosis of patients with selected B-cell hematologic malignancies, yet its use remains closely linked to treatment-related toxicities [1-5]. The most widely recognized adverse events are cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), both generally manageable with corticosteroids and the anti–IL-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab. Beyond these canonical and well-characterized toxicities, however, additional complications of comparable clinical relevance may occur. These include persistent cytopenias—defined as immune effector cell-associated hematologic toxicity (ICAHT) and the immune effector cell-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis–like syndrome (IEC-HS). Coagulopathy—bleeding and clotting events—has also been described as a non-canonical complication. Such events warrant particular attention and individualized management, as they may persist for months after CAR-T infusion, significantly compromise quality of life, and ultimately diminish the therapeutic benefit of CAR-T cells. In line with the 2023 guidelines, this manuscript seeks to provide a concise overview of these non-canonical post–CAR-T complications, summarizing current management strategies and proposing a practical diagnostic-therapeutic algorithm.

ICAHT: Immune Effector Cell–Associated Hematologic Toxicity

ICATH represents a severe complication, predisposing immunocompromised patients to recurrent infections and prolonged hospitalizations [6].

An international expert panel classified early ICAHT as cytopenias occurring within 30 days after CAR-T infusion, most often related to lymphodepleting chemotherapy, whereas late ICAHT refers to events beyond day +30. A grading system incorporating both depth and duration of neutropenia was proposed, reflecting the associated clinical consequences [2].

Several variables contribute to ICAHT development, including disease characteristics, prior lines of therapy, baseline marrow reserve, systemic inflammatory status, CAR-T product features, and post-infusion complications [7].

Three distinct patterns of neutrophil recovery have been described: a transient, chemotherapy-related “quick” recovery (~40% of cases); an “intermittent” biphasic course (~40%); and a clinically challenging “aplastic” phenotype (~20%), often refractory to G-CSF and associated with high morbidity and mortality [8].

The CAR-HEMATOTOX score was developed to stratify patients at risk of prolonged neutropenia, particularly those prone to the aplastic phenotype [8].The CAR-HEMATOTOX score combines parameters reflecting hematopoietic reserve (absolute neutrophil count [ANC], hemoglobin, platelet count) with markers of baseline inflammation (C-reactive protein and ferritin). It was validated using the occurrence of severe neutropenia (ANC <500/μL for ≥14 days within the first 60 days post–CAR-T infusion) as the primary endpoint. Patients classified as CAR-T Hematotox high-risk (score ≥2) demonstrated higher rates of severe infections—particularly of bacterial origin—along with increased non-relapse mortality and inferior overall outcomes compared with low-risk patients (score 0–1). These findings highlight the prognostic relevance of the score in stratifying infectious risk and treatment vulnerability [8].

The score may further serve as a clinical tool to guide supportive care. In particular, antibacterial prophylaxis and prophylactic G-CSF administration may be selectively targeted to high-risk patients, who derive greater benefit given their elevated incidence of febrile neutropenia and infectious complications. Additionally, the score may identify individuals warranting more comprehensive baseline diagnostic assessments, such as pre-CAR-T bone marrow biopsy [7–9].

Diagnostic Work-up of ICAHT

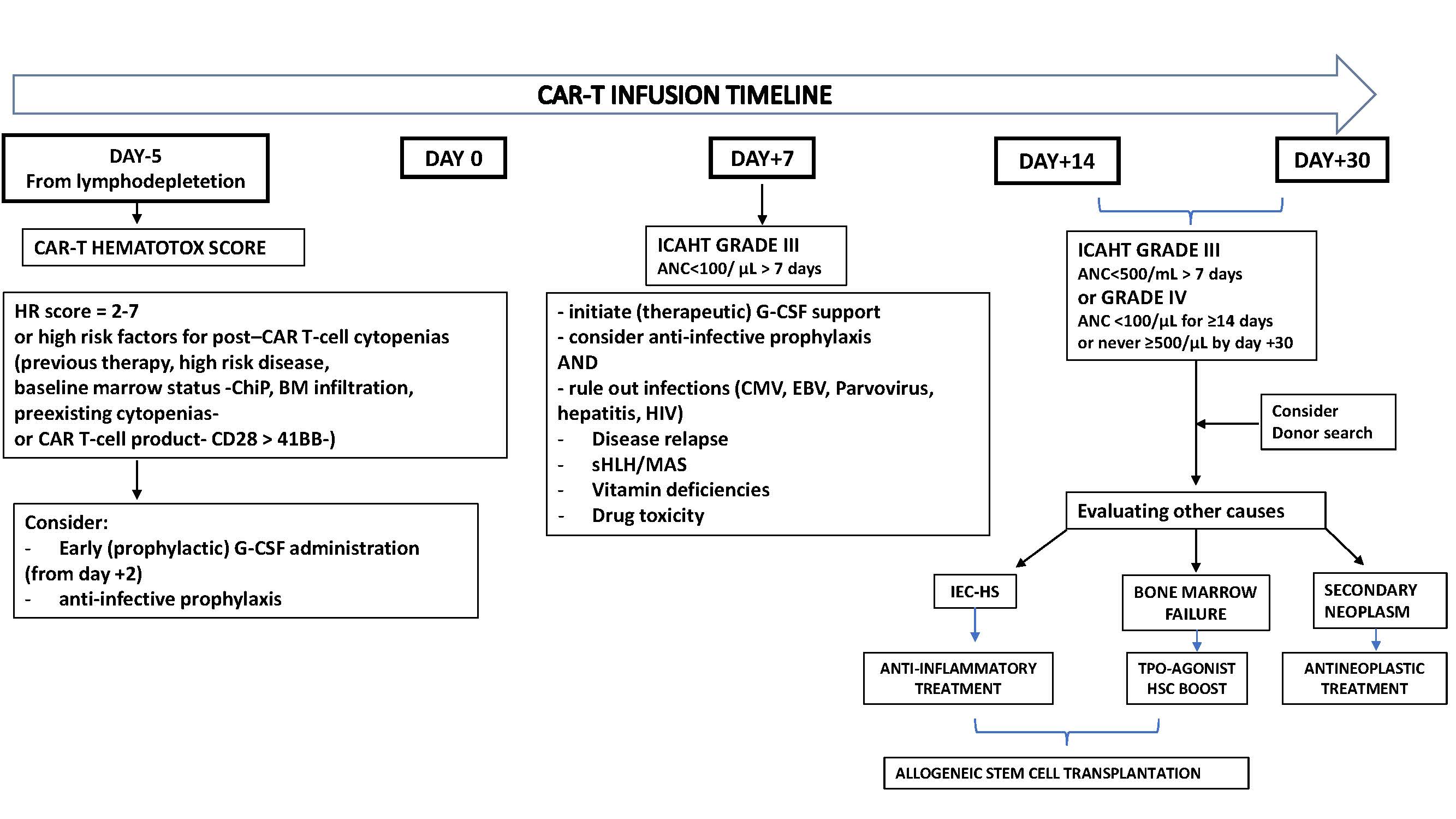

The diagnostic work-up of post-CAR-T cytopenia follows a stepwise approach. In patients with cytopenia persisting beyond the expected 2-3 weeks after infusion, the initial evaluation should exclude common and potentially reversible causes such as drug-induced myelosuppression, nutritional deficiencies, infections, ongoing inflammatory stress, disease relapse, or active bone marrow involvement. If these investigations remain inconclusive, second-line assessments are recommended in cases of grade ≥3 ICAHT or G-CSF–refractory cytopenia. These include viral studies and bone marrow aspiration with biopsy. In selected patients with profound and persistent marrow aplasia, cytogenetic analyses and next-generation sequencing may be warranted to rule out an underlying myeloid malignancy [7,8]. Figure 1 provides a concise diagnostic algorithm for the treatment and management of post-CAR-T cell cytopenia.

Figure 1. Diagnostic and therapeutic approach to prolonged cytopenias following CAR-T cells.

Management of ICAHT

Transfusion

Transfusional support is considered a cornerstone of post-infusion care. Supportive transfusions may include packed red blood cell concentrates to address anemia, as well as platelet concentrates to prevent or manage bleeding complications.

To minimize transfusion-related complications, the expert panel recommends that all cellular blood products be irradiated, starting 7 days before leukapheresis and continuing for at least 90 days after CAR T-cell infusion. Extension of this period may be required in selected patients, depending on conditioning regimens, underlying disease, or prior therapies that confer long-term immunosuppression [9,11].

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)

Initially, the use of G-CSF in the management of early post-CAR-T-cell therapy neutropenia was approached with caution, given concerns that it might exacerbate immune-mediated toxicities such as CRS or ICANS [12,13]. Subsequent evidence, however, has helped to clarify this issue [14]. For example, Miller et al. demonstrated that patients receiving prophylactic G-CSF before CAR-T infusion (predominantly pegylated formulations) achieved faster neutrophil recovery without compromising overall treatment outcomes or increasing the incidence of severe ICANS [15]. Importantly, in cases of low-grade CRS, G-CSF administration did not result in worsening severity. Similarly, Lievin et al. reported that early G-CSF administration (initiated on day +2) was associated with reduced rates of febrile neutropenia, again without a corresponding rise in high-grade CRS or ICANS [16]. Based on these data, early G-CSF (day +2) may be considered in high-risk patients to shorten the duration of severe neutropenia, while therapeutic G-CSF remains an option in cases of prolonged neutropenia (ANC<500/μL). Moreover, a lack of response to G-CSF may provide diagnostic insight into the aplastic recovery phenotype, whereas the majority (>80%) of patients ultimately respond to growth factor support. Nevertheless, recurrent or biphasic neutropenia may require repeated courses of therapeutic G-CSF.

Thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO)

The use of TPO, such as eltrombopag and romiplostim, has been explored as a therapeutic strategy for patients experiencing persistent or late-onset thrombocytopenia after CAR T-cell therapy, a complication most often observed during the second month following infusion [17]. Current evidence in this setting is extremely limited, being restricted to a few small case series from individual centers. In these reports, treatment with TPO agonists not only resulted in increased platelet counts but was also associated with improvements in hemoglobin levels and absolute neutrophil counts, enabling some patients to achieve independence from both platelet and red blood cell transfusions [18]. These findings mirror observations in acquired bone marrow failure syndromes, where TPO agonists have been shown to enhance multilineage hematopoiesis. In view of the absence of robust prospective data, expert recommendations suggest aligning the use of TPO agonists in the post-CAR T setting with practices established in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation, including consideration for patients with G-CSF-refractory cytopenias [9].

Infection prophylaxis

Infection prophylaxis after CAR-T therapy should be conducted in accordance with current EHA/EBMT guidelines [9]. These recommend antiviral prophylaxis and Pneumocystis jirovecii prophylaxis, as well as the administration of intravenous immunoglobulins in cases of clinically significant hypogammaglobulinemia. For antibacterial prophylaxis, the expert panel supports a risk-adapted approach, taking into account the individual patient’s infection risk profile, which is defined by the CAR-HEMATOTOX score, the depth and duration of neutropenia, and the local epidemiology and institutional protocols [8]. Specifically, patients with ANC below 500/µL and classified as high-risk according to the CAR-HEMATOTOX score are recommended to receive fluoroquinolone prophylaxis. Antifungal prophylaxis (e.g., with micafungin or posaconazole) is indicated in patients with grade 3 neutropenia, those with a history of allogeneic transplantation, prior invasive aspergillosis, or prolonged corticosteroid exposure.

Hematopoietic cell boost (HCB) and allogeneic stem cell transplantation (Allo-SCT)

Patients who remain unresponsive or refractory to G-CSF beyond day +14 following CAR-T cell infusion constitute a clinically challenging subgroup, as they are at high risk of developing severe and potentially fatal infections. In cases of severe ICAHT where an inflammatory trigger is suspected (such as concomitant CRS/ICANS or CRS/MAS), anti-inflammatory approaches including pulse-dose corticosteroids and/or cytokine-directed therapies (eg, tocilizumab or anakinra) may be warranted. An additional therapeutic option involves the use of cryopreserved autologous or allogeneic CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells collected prior to therapy (either before auto- or allo-HCT) [19]. Early administration of a readily available hematopoietic cell boost (HCB) has been associated with improved survival outcomes. Accordingly, the expert panel recommends considering HCB infusion without preceding conditioning chemotherapy in patients with grade ≥3 ICAHT persisting beyond day +14, provided that (1) a suitable boost is available and (2) refractoriness to G-CSF has been confirmed [20]. If the aforementioned strategies prove ineffective or unavailable and grade 4 ICAHT persists beyond day +30, the expert panel advises initiating a donor search for a potential allo-SCT as an ultima ratio. The decision to proceed with allo-HCT should be individualized and discussed on a case-by-case basis [21]. A time window between months 3 and 6 after CAR-T cell infusion was considered reasonable, balancing the elevated risk of infectious complications against the possibility of spontaneous hematologic recovery [9]. Once the decision to pursue allo-SCT has been made, critical aspects such as donor selection, conditioning regimens, and immunosuppressive strategies must be carefully evaluated. Given the paucity of experience and the scarcity of supporting evidence in this setting, only general considerations can currently be provided.

Immune Effector Cell-Associated Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis-Like Syndrome (IEC-HS)

The American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT) expert panel defines IEC-HS as a pathological and biochemical hyperinflammatory syndrome that occurs independently of CRS and ICANS [22]. Its diagnostic hallmarks include: (1) clinical and laboratory features consistent with macrophage activation or HLH; (2) attribution to immune effector cell therapy; and (3) association with progressive or new-onset cytopenias, hyperferritinemia, coagulopathy with hypofibrinogenemia, and/or elevated liver transaminases. In the setting of CAR-T cell therapy, the reported incidence of HLH-like manifestations ranges between 1% and 3.4%. In patients where ICAHT presents with HLH-like features, prompt initiation of anti-inflammatory therapy is essential to mitigate cytokine storm and its clinical consequences. First-line management should include anakinra, a recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, combined with high-dose corticosteroids. In refractory cases, additional interventions such as ruxolitinib, cytokine adsorption, or emapalumab—an interferon-γ–targeting antibody may be considered, although supporting evidence remains limited [23,24].

Coagulopathy

CAR-T cell recipients are susceptible to a spectrum of coagulation disorders, ranging from asymptomatic laboratory abnormalities to overt disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [25,26]. CRS and ICANS contribute through systemic inflammation and endothelial injury, favoring consumptive coagulopathy. More than half of patients may develop coagulation changes within the first month, with activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) prolongation and D-dimer elevation peaking around days 6–9, and fibrinogen nadir occurring around days 12–14. Despite frequent hypofibrinogenemia, major bleeding remains uncommon (~1.4%). Monitoring practices vary widely, and the utility of DIC scoring systems is uncertain. Current expert opinion supports testing at baseline and repeating only in cases of severe CRS or bleeding. Fibrinogen replacement with cryoprecipitate should be reserved for grade 3–4 CRS with fibrinogen <1 g/L, targeting >1.5 g/L until CRS resolution [27].

Bleeding and thrombosis

Bleeding events after CAR-T therapy occur most commonly within the first 30 days. In a retrospective series of patients with Large B-cell Lymphoma (LBCL), bleeding was reported in 11%, though severe cases were uncommon [28]. Risk was higher among older patients, those with prior bleeding history, baseline or concomitant thrombocytopenia, and in the presence of ICANS, consistent with its established link to endothelial dysfunction. Reports of cerebral hemorrhage, particularly during CRS or ICANS, may similarly reflect underlying endothelial injury.

Thrombotic events after CAR-T occur in 2–11% of patients, typically up to day +90, and are associated with ICANS and elevated D-dimer [29]. They can be safely managed with prophylactic or therapeutic anticoagulation, which is generally not linked to increased bleeding risk, with caution if platelet counts fall below 50,000/μL.

Conclusion

Taken together, these non-canonical toxicities share systemic problems: they tend to manifest late, persist for prolonged periods, and significantly impair quality of life, yet there are no standardized diagnostic frameworks, severity grading systems, or evidence-based interventions comparable to those available for CRS/ICANS. Current practice relies heavily on individualized risk assessment and extrapolation from transplantation guidelines, underscoring the urgent need for prospective multicenter studies, harmonized definitions, and robust management algorithms tailored to these distinct post–CAR-T complications. Multicenter collaborations, together with research incorporating in-depth molecular studies, will be essential to optimize resources, validate grading systems across diverse patient populations, and ultimately improve outcomes for patients experiencing these complex post–CAR-T toxicities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

References

2. Locke FL, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, Perales MA, Kersten MJ, Oluwole OO, et al. All ZUMA-7 Investigators and Contributing Kite Members. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel as Second-Line Therapy for Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2022 Feb 17;386(7):640–54.

3. Abramson JS, Solomon SR, Arnason J, Johnston PB, Glass B, Bachanova V, et al Lisocabtagene maraleucel as second-line therapy for large B-cell lymphoma: primary analysis of the phase 3 TRANSFORM study. Blood. 2023 Apr 6;141(14):1675–84.

4. Shah BD, Ghobadi A, Oluwole OO, Logan AC, Boissel N, Cassaday RD, et al. KTE-X19 for relapsed or refractory adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: phase 2 results of the single-arm, open-label, multicentre ZUMA-3 study. Lancet. 2021 Aug 7;398(10299):491–502.

5. Wang M, Munoz J, Goy A, Locke FL, Jacobson CA, Hill BT, et al. KTE-X19 CAR T-Cell Therapy in Relapsed or Refractory Mantle-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 2;382(14):1331–42.

6. Fried S, Avigdor A, Bielorai B, Meir A, Besser MJ, Schachter J, et al. Early and late hematologic toxicity following CD19 CAR-T cells. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019 Oct;54(10):1643–50.

7. Rejeski K, Subklewe M, Aljurf M, Bachy E, Balduzzi A, Barba P, et al. Immune effector cell-associated hematotoxicity: EHA/EBMT consensus grading and best practice recommendations. Blood. 2023 Sep 7;142(10):865–77.

8. Rejeski K, Perez A, Sesques P, Hoster E, Berger C, Jentzsch L, et al. CAR-HEMATOTOX: a model for CAR T-cell-related hematologic toxicity in relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2021 Dec 16;138(24):2499–513.

9. Hayden PJ, Roddie C, Bader P, Basak GW, Bonig H, Bonini C, et al. Management of adults and children receiving CAR T-cell therapy: 2021 best practice recommendations of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) and the Joint Accreditation Committee of ISCT and EBMT (JACIE) and the European Haematology Association (EHA). Ann Oncol. 2022 Mar;33(3):259–75.

10. Kopolovic I, Ostro J, Tsubota H, Lin Y, Cserti-Gazdewich CM, Messner HA, et al. A systematic review of transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2015 Jul 16;126(3):406–14.

11. Foukaneli T, Kerr P, Bolton-Maggs PHB, Cardigan R, Coles A, Gennery A, et al. Guidelines on the use of irradiated blood components. Br J Haematol. 2020 Dec;191(5):704–24.

12. Sterner RM, Sakemura R, Cox MJ, Yang N, Khadka RH, Forsman CL, et al. GM-CSF inhibition reduces cytokine release syndrome and neuroinflammation but enhances CAR-T cell function in xenografts. Blood. 2019 Feb 14;133(7):697–709.

13. Barreto JN, Bansal R, Hathcock MA, Doleski CJ, Hayne JR, Truong TA, et al. The impact of granulocyte colony stimulating factor on patients receiving chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Am J Hematol. 2021 Oct 1;96(10):E399–E402.

14. Galli E, Allain V, Di Blasi R, Bernard S, Vercellino L, Morin F, et al. G-CSF does not worsen toxicities and efficacy of CAR-T cells in refractory/relapsed B-cell lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020 Dec;55(12):2347–9.

15. Miller KC, Johnson PC, Abramson JS, Soumerai JD, Yee AJ, Branagan AR, et al. Effect of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on toxicities after CAR T cell therapy for lymphoma and myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2022 Nov 1;12(10):146.

16. Liévin R, Di Blasi R, Morin F, Galli E, Allain V, De Jorna R, et al. Effect of early granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor administration in the prevention of febrile neutropenia and impact on toxicity and efficacy of anti-CD19 CAR-T in patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2022 Mar;57(3):431–9.

17. Beyar-Katz O, Perry C, On YB, Amit O, Gutwein O, Wolach O, et al. Thrombopoietin receptor agonist for treating bone marrow aplasia following anti-CD19 CAR-T cells-single-center experience. Ann Hematol. 2022 Aug;101(8):1769–76.

18. Drillet G, Lhomme F, De Guibert S, Manson G, Houot R. Prolonged thrombocytopenia after CAR T-cell therapy: the role of thrombopoietin receptor agonists. Blood Adv. 2023 Feb 28;7(4):537–40.

19. Rejeski K, Burchert A, Iacoboni G, Sesques P, Fransecky L, Bücklein V, et al. Safety and feasibility of stem cell boost as a salvage therapy for severe hematotoxicity after CD19 CAR T-cell therapy. Blood Adv. 2022 Aug 23;6(16):4719–25.

20. Gagelmann N, Wulf GG, Duell J, Glass B, van Heteren P, von Tresckow B, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell boost for persistent neutropenia after CAR T-cell therapy: a GLA/DRST study. Blood Adv. 2023 Feb 28;7(4):555–9.

21. Lipsitt A, Beattie L, Harstead E, Li Y, Goorha S, Maron G, et al. Allogeneic CD34+ selected hematopoietic stem cell boost following CAR T-cell therapy in a patient with prolonged cytopenia and active infection. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2023 Mar;70(3):e30166.

22. Sandler RD, Tattersall RS, Schoemans H, Greco R, Badoglio M, Labopin M, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Secondary HLH/MAS Following HSCT and CAR-T Cell Therapy in Adults; A Review of the Literature and a Survey of Practice Within EBMT Centres on Behalf of the Autoimmune Diseases Working Party (ADWP) and Transplant Complications Working Party (TCWP). Front Immunol. 2020 Mar 31;11:524.

23. McNerney KO, DiNofia AM, Teachey DT, Grupp SA, Maude SL. Potential Role of IFNγ Inhibition in Refractory Cytokine Release Syndrome Associated with CAR T-cell Therapy. Blood Cancer Discov. 2022 Mar 1;3(2):90–4.

24. La Rosée P, Horne A, Hines M, von Bahr Greenwood T, Machowicz R, Berliner N, et al Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2019 Jun 6;133(23):2465–77.

25. Dong R, Wang Y, Lin Y, Sun X, Xing C, Zhang Y, et al. The correlation factors and prognostic significance of coagulation disorders after chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy in hematological malignancies: a cohort study. Ann Transl Med. 2022 Sep;10(18):975.

26. Johnsrud A, Craig J, Baird J, Spiegel J, Muffly L, Zehnder J, et al. Incidence and risk factors associated with bleeding and thrombosis following chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Blood Adv. 2021 Nov 9;5(21):4465–75.

27. Buechner J, Grupp SA, Hiramatsu H, Teachey DT, Rives S, Laetsch TW, et al. Practical guidelines for monitoring and management of coagulopathy following tisagenlecleucel CAR T-cell therapy. Blood Adv. 2021 Jan 26;5(2):593–601.

28. Hashmi H, Mirza AS, Darwin A, Logothetis C, Garcia F, Kommalapati A, et al. Venous thromboembolism associated with CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy in large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2020 Sep 8;4(17):4086–90.