Abstract

COVID-19 is a serious global health threat caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The virus enters human host cells through the recognition of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors or cluster of differentiation 147 (CD147) via the virus’s spike glycoprotein. Once inside the cell, SARS-CoV-2 uses its genomic RNA as template to produce the two overlapping polyproteins, pp1a and pp1ab, that are subsequently cleaved into 16 nonstructural proteins (NSPs). NSPs then form a replication–transcription complex (RTC) to generate new viral RNA genomes and the mRNAs essential for viral replication. Thus, NSPs can be good targets for the development of antiviral drugs against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Here, we review the nonstructural proteins of SARS CoV 2, focusing on their protein structure and function.

Keywords

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), COVID-19, Nonstructural proteins (NSPs), Antiviral

Introduction

COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) is a respiratory disease caused by a novel enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA beta coronavirus, denoted as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which belongs to the B lineage of beta-coronavirus.

The main transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is through respiratory droplets and fomites [1]. About 15-20% of infected people develop pneumonia and the lethality in high-risk groups, such as elderly people, immunodeficiency patients and people affected by chronic respiratory disease, obesity, and chronic heart diseases. While respiratory symptoms are recognized as the fundamental feature of the disease, there is abundant evidence that the disease is also associated with coagulation dysfunction leading to both venous and arterial thromboembolism [2]. This causes an increase in heart attacks, strokes, seizures, and Guillain-Barré syndrome including young people and increased mortality risk [3-6], framing SARS-CoV-2 as a serious global health threat.

SARS-CoV-2 enters the host cell through the recognition angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors by the spike glycoprotein present on the surface of the virus envelope. This is similar to SARS-CoV, but SARS-CoV-2 has a higher affinity due to a single N501T mutation in its S protein [7]. After binding with its receptor, the type II transmembrane serine protease (TMPRSS2) and several other lysosomal proteases cleave and activate the S glycoprotein to facilitate SARS-CoV-2 direct entry into the host cell by allow the viral capsid fuse with the host cell membrane [8]. Recently, another human receptor, CD147, has been identified as an additional route of viral entrance, again mediated by the spike protein [9-11].

Once inside the cell, SARS-CoV-2 genomic RNA acts as a messenger RNA (mRNA) that is translated by host ribosomes to produce two overlapping polyproteins, pp1a and pp1ab, from two open reading frames 1a and 1b (ORF1a and ORF1b). pp1a and pp1ab are cleaved into 16 nonstructural proteins (NSPs) by viral proteases NSP3 containing a papain-like protease (PLpro) domain and NSP5 (known as 3C-like main chymotrypsin-like protease—3CLpro, or the main protease—Mpro). After that, NSPs form a replication–transcription complex (RTC) to generate new RNA genomes and the mRNAs for the synthesis of viral components, including 4 structural proteins (spike protein, envelope protein, a membrane protein, and a nucleocapsid protein) and 9 accessory proteins to assemble the new viral particles [12-15].

NSP1 and NSP2 are assumed to play a role in host modulation to suppress the host antiviral response. A complex consisting of transmembrane proteins NSP3, NSP4, and NSP6 induces the formation of double-membrane vesicles (DMV), improving viral replication through membrane-associated replication. In addition to its own NSPs, SARS-CoV-2 recruits host proteins to form RTCs. A core component for the replication of SARS-CoV-2’s single-stranded RNA is RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). RdRp forms the replication complex together with NSP7 and NSP8. Together, they serve as a primase, generate short RNA primers for the primer-dependent RdRp, and increase its processivity. During infection of human cells, SARS-CoV-2 NSP9 was found to be essential for replication. NSP9 prefers ssRNA and is believed to interact with NSP8 in the replication complex. NSP13 and NSP10/NSP16 have helicase/triphosphatase and methyltransferase activity respectively and cap the nascent viral mRNA. The exonuclease (ExoN) of NSP14, endows the replication machinery with a proofreading function, thus increasing fidelity of SARS-CoV-2 RNA synthesis. The last protein of the replication complex is the uridine-specific endoribonuclease NSP15 (EndoU), which cleaves RNA uridylates at the 3′ position to form a 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiester product. It has also been shown to play a role in evading the host’s innate immune system [16-19].

The viral RNA replication machinery of SARS-CoV-2 can be a good target for development of antiviral drugs against SARS-CoV-2 infection through drug repurposing [20-22]. Currently, small-molecule compounds have predominantly targeted two conserved viral enzymes: Mpro [23,24] and RdRp [25]. In a recent study, remdesivir, an adenosine analog, was shown to bind to RdRp and inhibit its activity [26]. On May 1, 2020, FDA issued an emergency use authorization of remdesivir for the treatment of hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 symptoms. Favipiravir is an antiviral approved for pandemic influenza in Japan and was used as an experimental treatment for COVID-19, specifically acting as a broad-spectrum RdRp inhibitor. Hydroxychloroquine was thought to disrupt virus endocytosis, and lopinavir/ritonavir was thought to inhibit SARs-CoV-2 main protease [27]. Considering NSPs have necessary and conserved roles for viral replication within the viral life cycle and influence pathogenesis, such as mRNA capping (NSP14, NSP16), RNA proofreading (NSP14) and uridylate-specific endoribonuclease activity (NSP15) [28], they serve as promising targets for antiviral compounds development for treatment of COVID-19 [29].

Another approach for development of therapeutic interventions against SARS-CoV-2 infection has mainly focused on vaccination, structure-based antibodies strategies such as meplazumab (an anti-CD147 humanized antibody), and neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) from the plasma of recovered SARS-CoV-2 patients (monoclonal antibody 4A8, monoclonal antibody 47D11, monoclonal antibody CR3022, monoclonal antibodies B38 and H4, monoclonal antibodies CA1 and CB6, monoclonal antibody P2B-2F6, and antibody cocktail: REGN10987 and REGN10933) [10,30,31]. In November 2020, FDA issued an emergency use authorization of investigational monoclonal antibody therapy bamlanivimab (the potent anti-spike neutralizing antibody from Eli Lilly) for the treatment of mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in nonhospitalized adult and pediatric patients [32,33].

Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 was discovered to enter the cell through endocytosis with the entire viral particle, avoid confrontation by the host immune system, and multiply in the cytosol. Specifically, after SARS-CoV-2 spike protein binds to the ACE2 receptor, the virus can enter cell via endosomes, then host cysteine protease cathepsin L dependent activates viral spike proteins, the remaining S2 subunit facilitate virus fusion with the endosome membrane , and release its genome to the cytoplasm of the host cell [34]. This method of entry is regulated by many host factors, but most interestingly by cholesterol transporter Niemann-Pick type C (NPC1) [35,36] and two-pore channels (TPCs) [37]. Both NPC1 and TPCs are known to be important parts in CoV infectivity and could be targets for inhibiting SARS-CoV-2. NPC1 is key in SARS-CoV entry because the virus goes to NPC1-positive late endosomes and lysosomes, exploiting the extremely active cathepsin L protease there to trigger fusion mechanisms between itself and the host cell [38]. SARS-CoV-2 uses a similar mechanism [39]. On the other hand, TPCs help SARS-CoV-2 interact with endolysosomes and hasten the release plus transport of viral RNA to replication sites through modification of endolysosomes [40]. Interestingly, TPC inhibitors have been proven to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 entry into the cell and decrease the amount of RNA it releases in the cysotol [40]. Drugs such as chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine that make de-acidify endolysosomes have shown promise in combatting SAR-CoV-2 infection in vitro [41,42]. Thus, targeting the early interactions between the endolysosome pathway and SARS-CoV-2 could be another potential route of treating COVID-19.

Here, we review SARS-CoV-2’s nonstructural proteins’ similarity to their SAR-CoV counterparts [43] (Figure 1) while also focusing on their structure and function which hopefully can be resource for the development of efficient antiviral drugs against SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table 1).

Figure 1: SARS-CoV-2 sequence identity percent with SARS-CoV.

|

NSP |

Protein ID |

PDB Code |

Functions |

|

NSP1 |

YP_009724389.1 |

7K3N [44], 7K7P |

Inhibits the host mRNA translation [36] |

|

NSP2 |

YP_009725298.1 |

N/A |

Suppresses intracellular host signaling [46,47] |

|

NSP3 |

YP_009725299.1 |

Ubl1 domain (aa 1–111) 7KAG, ADRP/MacroD domain (aa 207–379): 6WEY, 6VXS/6W02/6W6Y/6WEN/6WCF [48]. PLpro domain (aa 748–1060): 6W9C/6WRH/6WZU/6XG3/7JIR/7JIT/7JIV/7JIW |

Releases NSP1, NSP2, and NSP3 and Participates host protein post-translation modifications [49,50] |

|

NSP4 |

YP_009725300.1 |

N/A |

Induces rearrangement of host cell membranes as double-membrane vesicles (DMVs) that serve as the scaffold for a viral replication/transcription complex (RTC) [51] |

|

NSP5 |

YP_009725301.1 |

6Y2G/6Y2F/6Y2E/6WQF [52], 6LU7/7BQY [53], 6LZE/6M0K [54], 6M03, 6W63, 6XG2/6XKF/6XKH/6XOA/7JFQ, 6ZRU/6ZRT [55], 6WNP, 7C7P [56], 7BRO [57] |

Main protease (Mpro), or 3C-like protease (3CLpro), cleaves the NSP polyprotein at 11 sites [52, 58,59] |

|

NSP6 |

YP_009725302.1 |

N/A |

Induces autophagosomes from ER, which help viral replication by assembly of replicase proteins in a modified membranous compartment derived from ER [60] |

|

NSP7 |

YP_009725303.1 |

6WQD, 6WTC/6WIQ |

Cofactor of NSP12, forms a hexadecamer with NSP8 as a primase [61,62] |

|

NSP8 |

YP_009725304.1 |

6WQD, 6WTC/6WIQ |

Cofactor of NSP12, forms a hexadecamer with NSP7 as a primase [61,62] |

|

NSP9 |

YP_009725305.1 |

6W4B, 6W9Q/6WC1 [63] |

RNA-binding protein, essential for both viral replication and virulence [64] |

|

NSP10 |

YP_009725306.1 |

6W61, 6W4H/6W75/6WKQ/6WJT/6WVN [65] |

Cofactor of NSP16 and NSP14 [66] |

|

NSP11 |

YP_009725307.1 |

N/A |

Function is unknown [67] |

|

NSP12 |

YP_009725307.1 |

6M71/7BTF [26], 7BV1/7BV2 [68] |

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), involves both replication and transcription of the viral genome [26] |

|

NSP13 |

YP_009725308.1 |

5RL9 |

Helicase |

|

NSP14 |

YP_009725309.1 |

N/A |

Bifunctional enzyme with N-terminal proofreading 3′-5′-exoribonuclease (ExoN) domain and C-terminal S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) dependent N7-methyltransferase domain (5'-cap RNA) [69] |

|

NSP15 |

YP_009725310.1 |

6W01/6VWW/6WLC/6WXC/6X1B |

Endoribonuclease that cleaves RNA at uridylates [28] |

|

NSP16 |

YP_009725311.1 |

6W61, 7C2J, 6W75/6W4H |

m7GpppA-specific, SAM-dependent, 2′-O-MTase [70] |

NSP1

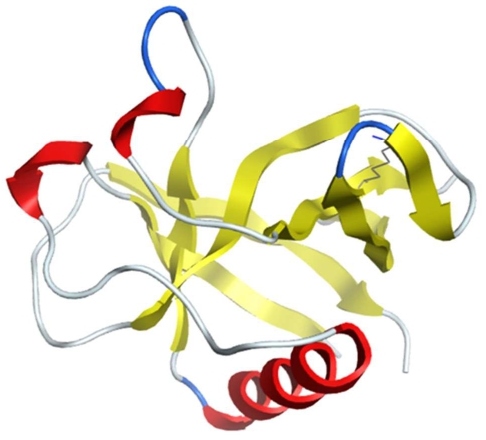

NSP1 of SARS-CoV-2 (PDB IDs: 7K3N/7K7P) has an 84% amino-acid sequence identity with SARS-CoV, suggesting similar properties and biological function of binding to the ribosome small subunit to inhibit the host’s mRNA translation. Figure 2 shows the 3D structure of SARS-CoV-2 NSP1 obtained using cryogenic electron microscopy. Researchers used structural analysis to confirm that SARS-CoV-2 NSP1-ribosome complexes C-terminus can bind to the human 40S ribosomal subunit with great inhibition efficiency, which may explain the enhanced pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2. The K164 was identified to be the key residue to interact with host 40S ribosomal subunits and suppress host gene expression by obstructing the mRNA entry tunnel, thus inactivating host messenger RNA (mRNA) translational activity [45,71]. SARS-CoV-2 NSP1 protein was also found to bind to the host mRNA export receptor NXF1–NXT1 and block nuclear export of cellular poly(A) RNA for translation [72]. Cellular studies show that SARS-CoV-2 NSP1 suppresses the induction of endogenous retinoic acid–inducible gene I (RIG-I) and interferon-stimulated gene product 15 (ISG15) upon IFN-β stimulation, which involves viral infection and pathogenesis [45]. Furthermore, NSP1 inhibits STAT1 phosphorylation leading to hyperactivity of STAT3 which is thought to be the cause of the many symptoms associated with COVID-19 such as lung inflammation [73]. Considering that SARS-CoV-2 NSP1 is one of three notable virulence factors (NSP1, NSP3c, and ORF7) that can inhibit host gene expression and suppress the host innate immune system, it could be a promising target for the development of antiviral therapy.

Figure 2: The structure of SARS-CoV-2 NSP1 (PDB: 7K3N).

A study of Chowdhury and Bagchi that used the 3D structure of SARS-CoV-2 NSP1 to perform in-silico virtual screening of the ChEMBL drug library, molecular docking simulations of the top six screened ligands, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the ligand–NSP1 complexes showed that the compounds named ligand1 (CHEMBL1096281), ligand4 (CHEMBL2022920), and ligand6 (CHEMBL175656) bind to the key amino-acid residues K164 and H165 with the strongest binding affinities to NSP1 apoprotein [74].

NSP2

NSP2 of SARS CoV-2 is a 638-amino-acid-long RNA-binding protein that may be involved in vesicle trafficking and interacts with the Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein and scar homology (WASH) complex component strumpellin [75]. The protein sequence of NSP2 of SARS-CoV-2 is 68% identical to SARS-CoV NSP2. Using tandem mass tag-multiplexed quantitative proteomics, the common NSP2 interactors were identified, including endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ signaling and mitochondria biogenesis [47]. Although SARS-CoV NSP2 can interact with host factors prohibitin 1 and prohibitin 2 to suppress intracellular host signaling [46], a similar function of SARS-CoV-2 NSP2 has not been discovered yet. Due to NSP2’s variability among different CoV strains, NSP2 possibly coevolves with hosts to acquire host-specific functions.

Angeletti and co-authors used the Datamonkey Adaptive Evolution Server and FUBAR (Fast, Unconstrained Bayesian AppRoximation) analysis of SARS CoV-2 ORF1ab containing NSP2 to identify the potential mutation sites under positive selection pressure [76]. The potential stabilizing mutation site was predicted to be at position 321 of the NSP2 protein. They prepared a homology model of SARS-CoV-2 NSP2, using SwissModel and HHPred servers, to map the structural variability and sites under pressure selection of the NSP2 [76]. There is a stabilizing mutation in the endosome-associated-protein-like domain of NSP2 that could explain SARS-CoV-2 high contagiousness. Stabilizing mutations under positive selection pressure in the endosome-associated-protein-like domain of NSP2 could explain SARS-CoV-2 high contagiousness [76]. After analysis of genomes of global SARS-CoV-2 variants, conserved C to U mutation at position 1059 (T85I) in NSP2 was identified to change the secondary structure of NSP2 RNA, resulting in a more stable RNA secondary structure due to an increase in Watson–Crick base pair probability for flanking regions. However, this does not affect interaction with human host miRNA and is involved in escaping human miRNA mediated anti-viral defense mechanism [77].

NSP3

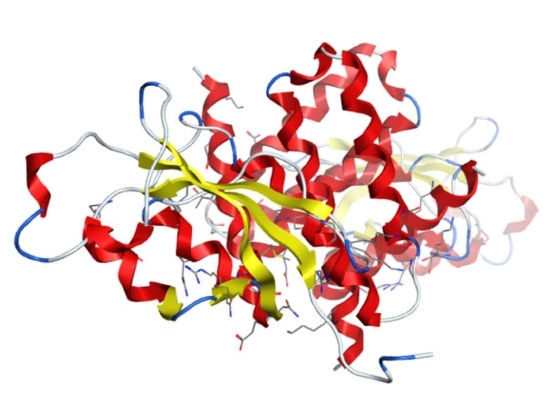

NSP3 is the largest nonstructural protein of SARS-CoV-2 that comprises multiple domains, including the ubiquitin-like domain 1 (Ub1, PDB ID: 7KAG), the acidic domain (hypervariable region), a macrodomain-X (PDB IDs: 6VX5/6W02/6W6Y/6WEN/6WCF/6WEY), SARS unique domains, papain-like protease 2 (PL2pro, includes ubiquitin-like domain 2—Ub2), catalytic core domain, (PDB IDs: 6W9C/6WRH/6WZU/6XG3/7JIR/7JIT/7JIV/7JIW), RNA-binding domain, marker domain, the Y domains, and two conserved transmembrane regions TM1 and TM2 (Figure 3). The PLpro domain can recognize the consensus sequence of LXGG/X to proteolyze the SARS-CoV-2 polyprotein to release NSP1, NSP2, and NSP3. These three NSPs form the replication/transcription complex with other viral NSPs as well as RNA. Other functions of papain-like protease 2 include removal of ubiquitin-like ISG15 that is typically induced upon viral infection and K48-linked polyubiquitin. PLpro also participates in host protein post-translation modifications by deubiquitinating and removing ISG15 through hydrolysis of ubiquitin and ISG15 [50,78,79]. This helps SARS-CoV-2 inhibit the host’s innate immune system through delaying type-I interferon responses and providing a window for the virus to replicate. Recent publication suggests that the macrodomain-X of NSP3 involves ADP-ribosylation of the proteins through its hydrolase activity as part of protein post-translational regulatory modifications [49]. Through these modifications as part of post-translational modification, macrodomain-X suppresses the host’s innate immune response. The multi-spanning transmembrane domains in NSP3 interacts with NSP4 and NSP6 to serve as a scaffold for the assembly of the membrane-associated RTC.

Figure 3: The structure of SARS-CoV-2 NSP3 (PDB 6W9C).

NSP4

NSP4 of SARS-CoV-2 is a 500-amino-acid transmembrane protein with four transmembrane helices and a conserved cytosolic C-terminal domain. It is the only protein of the viral polyproteins produced by both PLpro and Mpro. The protein sequence of SARS-CoV-2 NSP4 is 80% identical to SARS-CoV NSP4. Using tandem mass tag-multiplexed quantitative proteomics, researchers identified ER homeostasis factors as the unique SARS-CoV-2 NSP4 interactors [80]. Common NSP4 interactors include N-linked glycosylation machinery, unfolded protein response (UPR) associated proteins, and antiviral innate immune signaling factors. Considering that NSP4 interactors are localized at mitochondria-associated ER membranes, this suggests that NSP4 may be involved in modulating host calcium homeostasis [47]. SARS-CoV-2 NSP4 was assumed to interact with NSP3 and NSP6 to induce rearrangement of host cell membranes because DMVs serve as scaffolds for RTCs like SARS-CoV NSP4, which has an 80% sequence similarity with SARS-CoV-2 NSP4 [51].

NSP5

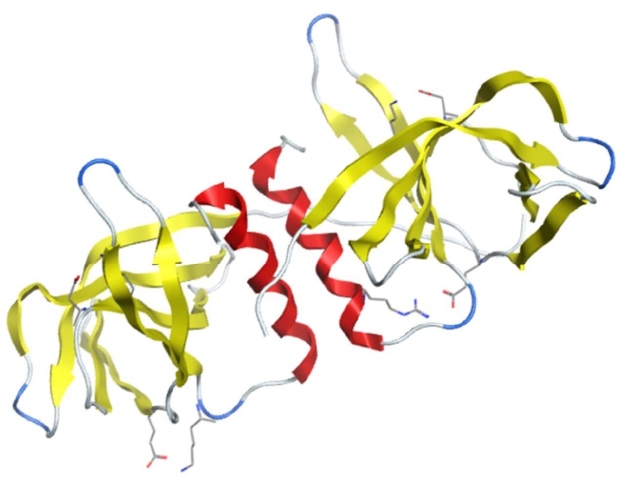

NSP5 is a cysteine protease with 306 amino acids also known as Mpro or 3CLpro. It is conserved among all human coronaviruses. NSP5 recognizes the sequence of LQ/(S/A/G) to proteolyze the SARS-CoV-2 polyproteins and release NSP4–NSP16 [59]. There are no human proteases that have similar cleavage specificity as NSP5, indicating that inhibitors for NSP5 can specifically block viral replication without toxicity. SARS-CoV-2 NSP5 monomer has three domains: domain I (residues 8–101), domain II (residues 102–184) and domain III (residues 201–303). Domains II and III are connected by a long loop (residues 185–200). Domains I and II form a deep cleft at the substrate-binding site that has a Cys–His (conserved residues H41 and C145) catalytic dyad located in the center of the cleft [58]. Through domain III, two monomers form a tight dimer with a higher catalytic activity as the N-finger (residues 1–7) of each protomer interacts with E166 of the other protomer. This shapes the S1 pocket of the substrate binding site that is essential for NSP5 enzyme activity [52].

Recently, the crystal structures of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro in complex with several ligands, including GLY, O6K, DMS (PDB IDs: 6Y2G/6Y2F/6Y2E) [52], N3 (PDB IDs: 6LU7/6M03/7BQY) [53], 11a/11b (PDB IDs 6LZE/6M0K) [54], boceprevir, and telaprevir (PDB IDs: 6ZRU/6WNP/6ZRT/7C7P), were published [81] (Figure 4). SARS-CoV-2 NSP5 is an attractive antiviral target because it is essential for viral replication and there are no similar human proteases.

Figure 4: The structure of SARS-CoV-2 NSP5 (PDB 6LU7).

Several inhibitors of Mpro have been identified through structure-based virtual screening. These include boceprevir, telaprevir (hepatitis C protease inhibitors), GC-376, calpain inhibitors II and XII [24,81], lopinavir, ritonavir, darunavir (HIV-1 protease inhibitors) [82], azithromycin [83], disulfiram, carmofur (pyrimidine analogue), ebselen, shikonin, tideglusib, PX-12, TDZD-8, N3 (an irreversible inhibitor), α-ketoamide inhibitors [53], and two peptide-like compounds (11a and 11b) [54].

Two HIV proteases (indinavir and amprenavir) and two hepatitis C viral protease inhibitors (boceprevir and telaprevir) were identified from FDA-approved drug library as potential inhibitors of Mpro by using a SARS-CoV-2 Mpro pharmacophore model [24]. In addition, several natural compounds plus their derivatives with anti-virus and anti-inflammatory effects exhibited high binding affinity to Mpro [84], including andrographolide derivatives, chrysin-7-O-β-glucuronide, betulonal, 2β-hydroxy-3,4-seco-friedelolactone-27-oic acid, isodecortinol and cerevisterol, hesperidin and neohesperidin, kouitchenside I and deacetylcentapicrin [85], bioflavonoids glycyrrhizic acid, baicalin, and rutin [86] and pentacyclic triterpenoid taraxerol [87]. In-vitro antiviral activity studies demonstrate that boceprevir GC-376, calpain inhibitors II and XII can inhibit replication of SARS-CoV-2 in cell-based assays [81].

NSP6

SARS-CoV-2 NSP6 is a transmembrane protein with six transmembrane domains and a highly conserved C-terminus. It locates to the host ER and is involved in the initial induction of autophagosomes from ER, helping viral replication through assembly of replicase proteins in a modified membranous compartment derived from the ER [60]. Like the Orf9c protein, SARS-CoV-2 NSP6 protein interacts with the Sigma receptor (Sig-1R) at the ER-mitochondrion contact called the mitochondrion-associated ER membrane (MAM), activating the ER’s stress response, which promotes viral replication by blocking ER-induced autophagosome/autolysosome vesicle [75]. In vitro, dextromethorphan (a Sigma-1 benzomorphan agonist) can increase SARS-CoV-2 viral titers, suggesting that Sigma receptors play a role in viral infection [75].

Using multiple SARS-CoV-2 viral assays, Gordon and colleagues (2020) identified two sets of antiviral compounds: inhibitors of the Sigma-1 and Sigma-2 receptors, which include haloperidol, PB28, PD-144418; along with hydroxychloroquine and inhibitors of mRNA translation. All these compounds demonstrate the remarkable reduction of SARS-CoV-2 viral infectivity in in-vitro cell assay [75]. Molecular-docking-based MD simulation studies suggest that strong binding of haloperidol with NSP6 is a possible antiviral mechanism [88]. Sig-1R ligands were found to have antiviral activity against hepatitis C, avian influenza A, and Ebola [89,90]. Inhibiting Sig-1R is a currently proposed mechanism to select the potential effective antiviral drugs to treat COVID-19 patients. Repurposing Sigma-1 receptor ligands through in-vitro screen of library of FDA-approved drugs is a potentially fast method to use antiviral drugs for COVID-19 therapy [91].

NSP7

The SARS-CoV-2 NSP7 protein (PDB IDs: 6WQD/6WTC/6WIQ) is an 83-amino-acid polypeptide with four α-helices: α1 (residues 4 to 19), α2 (residues 28 to 41), α3 (residues 45 to 61), and α4 (residues 68 to 75) (Figure 5). The protein sequence of SARS CoV-2 NSP7 has a 98.8% sequence identity with SARS-CoV NSP7 [43]. By forming a heterodimer with NSP8, NSP7 acts as co-factor of the RdRp NSP12 of SARS-CoV-2. NMR reveals that α2, α3, and α4 form a unique flat up-down-up α-helical in NSP7. NSP7 can form a hexadecameric complex with NSP8 as a dimer and then bind to NSP12’s core catalytic subunit to form the SARS-CoV-2 polymerase complex and stabilize the RNA binding site of NSP12. As a result, NSP12’s polymerase activity is significantly enhanced, although NSP12 itself has a low polymerase activity. A recent report about the crystal structure of the NSP7–NSP8 heterotetramer [61] revealed that the NSP7–NSP8 dimer could act as a primase and also a positively charged groove at the NSP7–NSP8 tetrameric interface serves as an RNA-binding site [62]. The interaction of SARS-CoV-2 NSP7 with Rashomology family member A (RHOA) may downregulate PAK1/2, ROCK1/2, and the phosphorylation of vimentin and stathmin proteins, changing the host cytoskeleton organization upon viral infection [75]. Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 NSP7 suppressed IFN-α signaling in an in-vitro cell study [92].

Figure 5: The structure of SARS-CoV-2 NSP7 (PDB: 6WQD).

NSP8

The SARS-CoV-2 NSP8 is a 198-amino-acid polypeptide that forms a hexadecamer with NSP7 (eight subunits of each). Using hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) and crosslinking mass spectrometry (XL-MS), the SARS-CoV-2 full-length NSP7–NSP8 complex was directly analyzed which suggest that the NSP7–NSP8 complex forms the linear heterotetramer structure in solution and can dissociate into a stable dimer to bind to NSP12 in the RTC [93]. NSP8 may participate in viral replication by acting as a primase. The N-terminal region of NSP8 is responsible for interaction with NSP7 [61] and has primase activity to synthesize complementary short oligonucleotides using ssRNA templates. This is then utilized as primers by NSP12 [62].

NSP9

NSP9 is a 113-amino-acid-long RNA-binding protein (PDB IDs: 6W4B/6W9Q/6WC1) conserved among beta coronaviruses (Figure 6). SARS-CoV-2 NSP9 amino-acid sequences has a 97% sequence identity with that of SARS-CoV [43]. SARS-CoV-2 NSP9 is essential for both viral replication and virulence. The SARS-CoV-2 NSP9 protomer is made up of seven β-strands (β1–β7) flanked by a N-terminal extension and a C-terminal α-helix. The β2–β3 and β3–β4 loops are glycine rich and are assumed to be used for RNA-binding. Predicted RNA-binding sites of the SARS-CoV-2 NSP9 dimer are between the beta strands β2 and β3, β4 and β5, and beta strand β7 and alpha-helix α1 [64]. SARS-CoV-2 NSP9 forms a dimer through an α-helical conserved protein–protein interaction motif G100xxxG104 by van-der-Waals interactions [63]. G100E and G104E mutations were lethal to the virus, indicating that dimerization of NSP9 at the GXXXG interface is required for viral growth. NSP9 K10A/R68A/K69A/R106A mutants reveals a significant loss of ssDNA binding affinity [94]. The crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 NSP9 is a horseshoe-like tetramer with two significant contact surfaces [94]. The structure of SARS-CoV-2 NSP9 in complex with a rhinoviral 3C protease sequence (LEVL) revealed that the extraneous LEVL residues could be accommodated into conserved cavity residues 100–105 (GMVLGS). The significance of this has yet to be established [63].

Figure 6: The structure of SARS-CoV-2 NSP9 (PDB: 6W4B).

A library of immunomodulatory medicinal compounds with antiviral capability were screened against SARS-CoV-2 nonstructural proteins NSP9 and NSP15. Six compounds-arzanol, ferulic acid, genistein, resveratrol, rosmanol, and thymohydroquinone—were identified and showed significant binding with NSP9. These compounds formed hydrogen bonds with R40 and S60 except for genistein, which has a chemical affinity for V42 [95]. Structure-based drug repurposing for targeting SARS-CoV-2 NSP9 identified conivaptan, which is an arginine vasopressin antagonist drug, as a high affinity compound [96]. Virtual screening by docking and MD suggests that lapachol derivatives could be potential antiviral drug through binding SARS-CoV-2 NSP9 [97].

NSP10

NSP10 is 139-amino-acid-long zinc-binding protein and can bind to RNA (PDB IDs: 6W61/6W4H/6W75/6WKQ/6WJT/6WVN) (Figure 7). NSP10 has two subdomains: a helical α subdomain (helices α1–α4 and α6) and a β subdomain (β1 and β2). There are two zinc binding sites; one is located at α-subdomain (helices α2 and α3) formed with residues C74, C77, C90 and a histidine residue (H83) and the other is at the C-terminus formed by residues C117, C120, C128, and Cys130 [66]. NSP10 does not have any specific enzymatic activity. Rather, it functions as a cofactor for NSP14 and NSP16. NSP10 forms the NSP14–NSP10 complex, which is exclusively required for ExoN activity of SARS-CoV-2, but not the guanine-N7-MTase activity of NSP14. Mutation studies suggest residues of F19, G69, S72, H80 and Y96 in NSP10 provide the key interactions to bind NSP10 to NSP14 [69]. NSP10 can stabilize the SAM-binding pockets of NSP16, stimulates its enzymatic activities to methylate the ribose 2′-O of the first nucleotide, and convert viral mRNA from the Cap-0 (me7GopppA1) to the Cap-1 form (me7GopppA1m). Cap-1 allows the viral RNA to mimic cellular mRNA and enhance its translation [70]. The NSP10/NSP16 heterodimer catalyzes methylation of the first nucleotide at the ribose 2′-O position of the viral mRNA cap, preventing the host’s innate immune system from recognizing the virus’s mRNA.

Figure 7: The structure of SARS-CoV-2 NSP10 (PDB: 6W61).

The crystallized structure of NSP10-NSP16 2′-O-methylase suggests that the conserved SAM-binding pocket and the RNA-binding groove could be targeted as a potential treatment for COVID-19 [98]. Sinefungin, a pan-MTase inhibitor, binds to the SAM-binding pocket within NSP16. The residues N99, N101, and D114 form hydrogen bonds with nucleoside and other residues N43, N130, and K170 recognize methionine. All of these six residues are highly conserved [66].

NSP11

NSP11 is a 13-amino-acid-long polypeptide, which is the cleavage product of pp1a by Mpro. Although there is a cleavage site between NSP10 and NSP11 in which pp1a can be recognized by Mpro, no cleavage site between NSP11 and NSP12 was found. Considering that this cleavage site is also between pp1a and pp1b, the missing cleavage site may allow pp1ab to be expressed as a longer polypeptide through ribosomal frameshifting, which is subsequently is cleaved to produce 16 nonstructural proteins [99]. It is identified as an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP). Its function is unknown [67]. A recent publication suggests that NSP11 did not accumulate any mutations [100].

NSP12

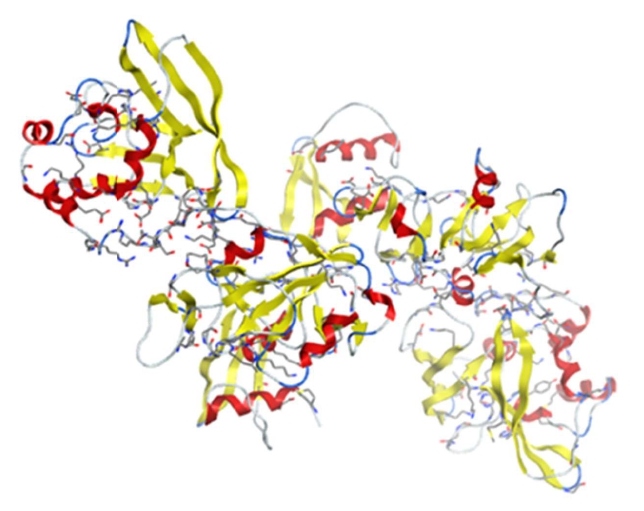

NSP12, also called RdRp, is a 932-amino-acid-long protein (PDB IDs: 6M71/7BTF/7BV1/7BV2) involved in both replication and transcription of the viral genome (Figure 8). SARS-CoV-2 NSP12 amino-acid sequences has an over 95% sequence identity to the SARS-CoV polymerase [43]. NSP12 contains an N-terminal nidovirus RdRp-associated nucleotidyltransferase (NiRAN) domain (residues D60 to R249), an interface domain (residues D29 to K50), and a C-terminal RdRp catalytic domain (residues S367 to F920) that is composed of the finger, palm, and thumb. The NSP12 core catalytic subunit binds with a NSP7-NSP8 heterodimer and also binds to a second NSP8 subunit to form the SARS-CoV-2 polymerase complex. The active site of the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp domain is formed by the conserved motifs A to G in the palm domain. Motif C contains the catalytic residues SDD (residues 759 to 761) [26]. NSP12 itself has extremely low polymerase activity for RNA synthesis. When forming NSP12–NSP7–NSP8 complex, cofactors NSP7 and NSP8 form a heterodimer that binds to the thumb subdomain of RdRp and an additional NSP8 subunit binds to the top region of the finger subdomain of NSP12. RdRp polymerase activity is significantly enhanced as a result [101].

Figure 8: The structure of SARS-CoV-2 NSP12 (PDB: 6M71).

The cryoelectron-microscopy structure of an active form of SARS-CoV-2 RdRp product duplex, including NSP12, NSP8, and NSP7, and more than two turns of RNA template (11 base pairs per turn) revealed a unique feature of NSP12 complex: a long protruding RNA (second turn RNA) binding with extended protein regions (like sliding poles) in two copies of NSP8. Amino acid K58 in this NSP8 extended protein region is critical for binding the exiting RNA, which allows NSP8 slide along exiting RNA and prevents premature dissociation [25]. Residues N691, S682, and D623 in NTP-binding site of NSP12 are responsible for specific synthesis of RNA through recognizing the 2′-OH group of the NTP. Considering that the viral RdRp is essential for replication of SARS-CoV-2, nucleotide analogues like remdesivir could be used as antiviral treatment for COVID 19. In-vitro studies suggested that the remdesivir can efficiently inhibit SARS-CoV-2 RdRp through its triphosphorylated form, competing with ATP to bind to the NTP site (residues N691, S682 and D623) in NSP12, causing RNA-chain synthesis delayed termination at position i+3 [25,102].

NSP13

NSP13 is a 601-amino-acid-long multifunctional protein (PDB ID: 5RL9). SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 amino-acid sequence has 99.8% sequence identity to that of SARS-CoV with the only amino-acid residue different (isoleucine vs. valine), suggesting a high degree of functional conservation [43]. NSP13 has five domains: a zinc-binding domain (residues 1–99), a stalk domain (residues 100–149), a 1B domain (residues 150–260), a 1A domain (“RecA-like” domain residues 261–441), and a 2A domain (“RecA-like” domain residues 442–596) (Figure 9). Domains 1A, 1B, and 2A are responsible for nucleic-acid binding along with ATP hydrolysis. The zinc-binding and stalk domains are essential for the helicase activity. NSP13 belongs to superfamily 1 helicase (SF1) superfamily. It catalyzes the unwinding of duplex RNA and DNA into single strands in the 5′-3′ direction by hydrolyzing NTPs. NSP13’s helicase activity helicase is magnesium dependent [103]. It has been shown that the binding of NSP12 with NSP13 can stimulate the helicase activity of NSP13. SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 is also known to possess 5′-triphosphatase activity, involving the introduction of 5′-terminal caps to the viral mRNA. Considering NSP13 is highly conserved in all coronaviruses and is an essential enzyme in viral replication, this makes NSP13 an ideal target for antiviral treatment.

Figure 9: The structure of SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 (PDB: 5RL9).

The homology model of the SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 predicted six key residues (K288, S289, D374, E375, Q404, and R567) inside the binding pocket of NTP hydrolysis active site, similar to SARS-CoV. Virtual screening identified four compounds—cmp1, cmp3a, cmp11, and cmp15—to significantly bind with those six key residues [104]. Virtual screening and MD based on the homology model of NSP13 revealed potential inhibitors of NSP13, including cepharanthine, cefoperazone, dihydroergotamine, cefpiramide, ergoloid (dihydroergocristine), ergotamine, netupitant, DPNH (NADH), lifitegrast, nilotinib, and tubocurarin [105].

SSYA10-001 (a 1,2,4 triazole) blocks SARS-CoV replication by inhibiting NSP13 helicase activity without affecting ATPase activity. A putative binding pocket, including residues Y277, R507, and K508, for SSYA10-001 was identified via mutation assay [106]. Given the 99.8% sequence homology of helicase in SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, SSYA10-001 should be tested for its inhibition activity against SARS-CoV-2 NSP13.

NSP14

SARS-CoV-2 NSP14 is a 527-amino-acid-long bifunctional enzyme, which has a N-terminal proofreading 3′-5′ ExoN domain (the amino acids 1–290) and a C-terminal S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) dependent N7-methyltransferase domain (the amino acids 291–527). Its amino-acid sequences have a 99.1% sequence homology with SARS-CoV NSP14, suggesting a high degree of functional conservation. Along with the cofactor NSP10, NSP14’s ExoN activity is metal-dependent (Mg2+ and Mn2+) and acts on both ssRNA and dsRNA in a 3′ to 5′ direction to remove mismatches during RNA replication. NSP14’s ExoN activity depends on the conserved DEED motif with conserved residues D90/E92 (motif I), D243 (motif II), and D273 (motif III) [69]. Specifically, residues E92, D243 and D273 are important for substrate binding and its catalytic activity. E92 was also found to form a hydrogen bond with residue H268, anchoring the substrates and facilitating the second Mg2+ ion for catalytic reaction. Furthermore, compared to other coronaviruses, motif I of the SARS-CoV-2 NSP14 ExoN domain is required for its function [69].

Using SARS-CoV-2 N7-methyltransferase homology model based on crystal structure of the SARS-CoV NSP14–NSP10 complex (PDB ID: 5C8S), then above-mentioned paper showed that the residue Asn388 is highly conserved and core residue for guanosine-p3-adenosine-5′,5′-triphosphate (G3A) binding and that Asn306, Arg310, and Trp385 are additional residues for substrate reaction [107].

Sinefungin, a dinucleotide, was identified as a more potent and specific SARS-CoV-2 NSP14 N7-MTase inhibitor compared to other broad-spectrum MTase inhibitors. Molecular docking suggests that it binds to a pocket formed by the SAM and cap RNA binding sites. N-adenosine at the 2′-O position can form hydrogen bonds with G333 (3′-OH), I338 (5′-OH), K336 (N7), and H424 (N1) residues [108]. Another virtual screening of SARS-CoV-2 NSP14 using SARS-CoV NSP14 (PDB: 5NFY) homology model as a template identified four drugs—saquinavir, hypericin, baicalein, and bromocriptine—as potential inhibitors of NSP14. They could bind to key amino-acid residues in both active centers of the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of NSP14 [109].

Additional virtual screening based a homology model of SARS-CoV-2 NSP14 was performed on 10 427 approved drug conformers. Three known antivirals—conivaptan, hesperidin and glycyrrhizic acid, were identified. These drugs have known inhibitory effects on beta coronaviruses in vitro and in patients. Hesperidin is the only drug that interacts with all five catalytic residues [110]. Recent in-silico screening of NSP14 inhibitor suggest that ritonavir can bind to the exoribonuclease active site through interaction with three catalytic residues: D90, E92, and H268. This suggests that it may serve as an effective inhibitor of the ExoN activity of NSP14 [111]. By using an in-vitro radiometric methyltransferase assay, seven SAM competitive methyltransferase inhibitors were identified. Compound SS148can inhibit NSP14 MT activity with low IC50 [112]. By using a mass-spectrometry-based high-throughput screen, 12 SARS-CoV-2 NSP14 N7-MTase inhibitors were identified from 1771 FDA-approved small-molecule drugs library. Nitazoxanide (anti-infective drug) was confirmed as a selective methyltransferase inhibitor of NSP14 and is in a clinical trial for treatment of COVID 19 [113].

NSP15

NSP15 is a 346-amino-acid-long uridylate-specific endoribonuclease that cleaves RNA at uridylates at the 3′ position (PDB IDs: 6W01/6VWW/6WLC/6WXC/6X1B) (Figure 10). Mn2+ is required as a cofactor for NSP15 to cleave RNA through the transesterification reaction [114]. Its amino-acid sequences have 97.7% similarity with NSP15 from SARS-CoV. NSP15 is conserved in all coronavirus family members, suggesting that its function is critical for the viral life cycle [28]. Studies showed that NSP15 deficient coronavirus could replicate well in host cells, indicating that NSP15 is not essential for viral RNA synthesis. Instead, it is suggested that NSP15 can suppress the host protective innate immune response by evasion of host pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) detecting viral dsRNA through controlling the length of polyuridines at the 5′ end of negative-strand viral RNA [115]. Through these mechanisms, NSP15 is essential for coronavirus replication in host cells [116].

Figure 10: The structure of SARS-CoV-2 NSP15 (PDB: 6W01).

NSP15 is active as a hexamer consisting of a dimer of trimers. Its monomer has three domains: a N-terminal domain that is responsible for oligomerization to form trimer, a middle domain, and a C-terminal domain that is an endonuclease (EndoU) domain containing the active site residues responsible for uridylate-specific cleavage [117]. Recent publication revealed the first two crystal structures of SARS-CoV-2 NSP15 with 1.90 Å and 2.20 Å resolution. The active site in the C-terminal EndoU domain of SARS-CoV-2 NSP15 has six key residues: H235, H250, K290, T341, Y343, and S294. H235, H250, and K290 are suggested to be a catalytic triad for their nuclease activity [28,117]. S294 and Y343 determine uridine specificity [117]. In crystal structure of NSP15 citrate-bound form (NSP15/cit), the citrate ion was revealed to stabilize the active site residues by forming hydrogen bonds with active site residues, H235, H250, K290, and T341 [28]. In new crystal structures of NSP15 in complex with uridine-5′-monophosphate (5′-UMP); uridine-3′-monophosphate (3′-UMP); 5′-GpU RNA dinucleotide; uridine 2′,3′-vanadate; and tipiracil (synthetic uracil analog), the active site of NSP15 can bind all five ligands through active site residues of each monomer independently [118]. Tipiracil was also found to competitively inhibit NSP15 RNA nuclease activity and modestly decreases SARS-CoV-2 virus replication in vitro without affecting viability of host cells [118]. Using a virtual screening method, six compounds-arzanol, ferulic acid, genistein, resveratrol, rosmanol, and thymohydroquinone—were suggested to possess strong binding affinity for NSP15 [119]. Using a pharmacophore model of the functional centers of SARS-CoV-2 NSP15, 21 compounds from an FDA-approved drug database were identified as potential antiviral NSP15 inhibitors. These compounds are already used in treatment for a range of viruses, including HIV, hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV), influenza and herpes simplex virus (HSV). Some of the compounds even demonstrated inhibition activity for MERS, SARS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2. Specifically, amprenavir, antiretroviral protease inhibitor, showed activity against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro (Manuscript in preparation).

NSP16

NSP16 is a 298-amino-acid-long m7GpppA-specific, SAM-dependent, 2′-O-MTase (PDB IDs: 6W4H/ 6W61/6W75/7C2J) (Figure 11). NSP16 together with NSP10 can recognize the N7-methylated RNA cap and methylates its 2′-hydroxy group of adenines using SAM as donor of methyl for further methylation at the 2′-O position of mRNA and generates the cap-1 and cap-2 structures. This methylation protects viral mRNA from being recognized by intracellular pathogen recognition receptors such as IFIT and RIG-I. SARS-CoV-2 NSP16 amino-acid sequences were 99% identical with SARS-CoV NSP16 [43]. Cofactor NSP10 promotes opening of NSP16’s SAM and RNA binding pockets, stimulating NSP16’s enzymatic activity [70].

Figure 11: The structure of SARS-CoV-2 NSP16 (PDB: 6W4H).

The crystal structure of the SARS-CoV-2 NSP10–NSP16 heterodimer in complex with SAM revealed that the SAM binding pocket is formed by three loops (residues 71–79, residues 100–108, and residues 130–148), the cap-binding groove is composed of two flexible loops (residues 26–38 and residues 130–148), and that the 2′-O-MTase catalytic core includes a Rossmann-like β-sheet fold decorated by eleven α-helices, seven β-strands, and loops. Residues K46, D130, K170, E203 comprises a motif for methyl-transfer and mRNA binding near the SAM methyl group is catalytically transferred to the 2′-O sugar [65]. Residues contributing to SAM binding with NSP16–NSP10 complex heterodimer include N43, Y47, G71, S74, D99, L100, D114, C115, M131, Y132, and F149 through hydrogen bonds and water-mediated interactions. SAM forms stable H-bond with residues Y47, G71, D99, and D130, which are attractive targets for SAM competitive inhibitors like sinefugin [98,120]. Through a high-resolution structure of SARS-CoV-2 RNA cap/NSP10/NSP16 complex, an additional SARS-CoV-2 specific ligand-binding site was identified which can accommodate small molecules outside of the catalytic pocket [70].

The crystal structure of the NSP10–NSP16 complex with sinefungin revealed that the nucleoside part of sinefungin forms hydrogen bonds with residues D99, N101, and D114 while the amino-acid part is recognized by N43, D130, and K170 [66]. These six residues—D99, N101, D114, N43, D130, and K170—are highly conserved among SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV. Previous research used the DoGSiteScorer software [121]. to analyze the druggability of all binding sites of SARS-CoV-2 NSP10–NSP16; SAM pocket has the highest score. Further virtual screening identified several top hits for potential NSP16 2′-O-MTase inhibitors, including MK3207, rebastinib, hesperidin, entrectinib, and osi-027. Among them, the most promising drug is hesperidin, an antiviral against influenza A virus (H1N1), and EV-A71 (enterovirus) [121].

Conclusion

The majority of SARS-CoV-2 nonstructural proteins have the essential role in viral RNA replication and transcription through complex RNA replication/transcription machinery. Some NSPs also participate in blocking expression of the host gene and suppressing the host innate immune responses, key for SARS-CoV-2 to safely multiply inside the body. NSP5, NSP9, NSP12, NSP13, NSP 14, NSP15, and NSP16 can be used as the targets for antiviral treatment due to their importance for the virus’s lifecycle which is suggested by the high sequence similarity of these NSPs and their counterparts in SARS-CoV-1. Specifically, the targeting above proteins is important because inhibiting NSP5 could lead to the body more readily recognizing and destroying the virus and inhibiting the other NSPs could lead to a halt in SARS-CoV-2’s viral replication cycle, both of which would stop the virus from multiplying. Remdesivir, a drug currently approved to treat hospitalized COVID19 patients, targets NSP12 and NSP14 with its antiviral activity. Other nucleoside analogs like ribavirin, favipiravir, and favilavir are being tested for inhibition of SARS-COV 2 NSP12 [122].

With more of these NSPs crystal structural released and function understood, we can use structural based approach on virtual screening to efficiently identify and repurpose FDA-approved antiviral inhibitors for COVID-19 treatment.

Funding Information

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ Contributions

JYT: Collection and analysis of information, writing of the review. IFT and VLK: Outlining the structure of the article, review, supervision, and revision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The author(s) declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

2. Malas MB, Naazie IN, Elsayed N, Mathlouthi A, Marmor R, Clary B. Thromboembolism risk of COVID-19 is high and associated with a higher risk of mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 Dec;29:100639

3. Hassett CE, Frontera JA. Neurologic aspects of coronavirus disease of 2019 infection. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2021 Jun 1;34(3):217-27.

4. Hsu A, Ohnigian S, Chang A, Liu Y, Zayac AS, Olszewski AJ, et al. Thrombosis in COVID-19: A narrative review of current literature and inpatient management. Rhode Island Medical Journal. 2021 Jun 1;104(5):14-9.

5. Khryshchanovich VY, Rogovoy NA, Nelipovich EV. Arterial thrombosis and acute limb ischemia as a complication of COVID-19 infection. The American Surgeron. 2021 May 28; 31348211023416.

6. Nejad JH, Heiat M, Hosseini MJ, Allahyari F, Lashkari A, Torabi R, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with COVID-19: A case report study. Journal of Neurovirology. 2021 May 27;1–4.

7. Zhang H, Penninger JM, Li Y, Zhong N, Slutsky AS. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: Molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Medicine. 2020 Apr;46(4):586-90.

8. Shang J, Wan Y, Luo C, Ye G, Geng Q, Auebach A, et al. Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2020 May 26;117(21): 11727-34.

9. Wang K, Chen W, Zhang Z, Deng Y, Lian JQ, Du P, et al. CD147-spike protein is a novel route for SARS-CoV-2 infection to host cells. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2020 Dec 4;5(1):283.

10. Helal MA, Shouman S, Abdelwaly A, Elmehrath AO, Essawy M, Sayed SM, et al. Molecular basis of the potential interaction of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to CD147 in COVID-19 associated-lymphopenia. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020 Sep 16:1-11.

11. Faghihi H. CD147 as an alternative binding site for the spike protein on the surface of SARS-CoV-2. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020 Dec;24(23):11992-11994.

12. Kim D, Lee JY, Yang JS, Kim JW, Kim VN, Chang H. The Architecture of SARS-CoV-2 Transcriptome. Cell. 2020 May 14;181(4):914-921.

13. Wu A, Peng Y, Huang B, Ding X, Wang X, Niu P, et al. Genome Composition and Divergence of the Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Originating in China. Cell Host Microbe. 2020 Mar 11;27(3):325-328.

14. Naqvi AAT, Fatima K, Mohammad T, Fatima U, Singh IK, Singh A, et al. Insights into SARS-CoV-2 genome, structure, evolution, pathogenesis and therapies: Structural genomics approach. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020 Oct 1;1866(10):165878.

15. Astuti I, Ysrafil. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): An overview of viral structure and host response. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020 Jul-Aug;14(4):407-412.

16. Finkel Y, Mizrahi O, Nachshon A, Weingarten-Gabbay S, Morgenstern D, Yahalom-Ronen Y, et al. The coding capacity of SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2021 Jan;589(7840):125-130.

17. V’Kovski P., Kratzel A., Steiner S., Stalder H., Thiel V. Coronavirus biology and replication: Implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19:155–170.

18. Sola I., Almazán F., Zúñiga S., Enjuanes L. Continuous and Discontinuous RNA Synthesis in Coronaviruses. Annu Rev Virol. 2015;2:265–288.

19. Yadav R, Chaudhary JK, Jain N, Chaudhary PK, Khanra S, Dhamija P, et al. Role of Structural and Non-Structural Proteins and Therapeutic Targets of SARS-CoV-2 for COVID-19. Cells. 2021 Apr 6;10(4):821.

20. Drożdżal S, Rosik J, Lechowicz K, Machaj F, Kotfis K, Ghavami S, et al. FDA approved drugs with pharmacotherapeutic potential for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) therapy. Drug Resistance Updates. 2020 Dec; 53:100719.

21. Eydoux C, Fattorini V, Shannon A, Le TTN, Didier B, Canard B, et al. A fluorescence-based high throughput-screening assay for the SARS-CoV RNA synthesis complex. Journal of Virological Methods. 2021 Feb;288: 114013.

22. Zhou Y, Hou Y, Shen J, Huang Y, Martin W, Cheng F. Network-based drug repurposing for novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2. Cell Discovery. 2020 Mar 16;6(1):14.

23. Goyal B, Goyal D. Targeting the dimerization of the main protease of coronaviruses: A potential broad-spectrum therapeutic strategy. ACS Combinatorial Science. 2020 Jun 8;22(6):297-305.

24. Kouznetsova VL, Huang DZ, Tsigelny IF. Potential SARS-CoV-2 protease M(pro) inhibitors: Repurposing FDA-approved drugs. Physical Biology. 2021 Feb 9:18(2):025001.

25. Hillen HS, Kokic G, Farnung L, Dienemann C, Tegunov D, Cramer P. Structure of replicating SARS-CoV-2 polymerase. Nature. 2020 Aug;584(7819):154-6.

26. Gao Y, Yan L, Huang Y, Liu F, Zhao Y, Cao L, et al. Structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from COVID-19 virus. Science. 2020 May 15;368(6492):779-82.

27. Magro G. COVID-19: Review on latest available drugs and therapies against SARS-CoV-2. Coagulation and inflammation cross-talking. Virus Research. 2020 Sep;286:198070.

28. Kim Y, Jedrzejczak R, Maltseva NI, Wilamowski M, Endres M, Godzik A, et al. Crystal structure of NSP15 endoribonuclease NendoU from SARS-CoV-2. Protein Science. 2020 Jul;29(7):1596-605.

29. Liu XH, Zhan X., Lu ZH, Zhu YS, Wang T. Potential molecular targets of nonstructural proteins for the development of antiviral drugs against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Biomed. Pharmacotherapy. 2021 Jan;133: 111035.

30. Le TT, Andreadakis Z, Kumar A, Gómez Román R, Tollefsen S, Saville, M, et al. The COVID-19 vaccine development landscape. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2020 May;19(5):305–6.

31. Le TT, Cramer JP, Chen R, Mayhew S. Evolution of the COVID-19 vaccine development landscape. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2020 Oct;19(10):667-8.

32. Gottlieb RL, Nirula A, Chen P, Boscia J, Heller B, Morris J, et al. Effect of Bamlanivimab as Monotherapy or in Combination with Etesevimab on Viral Load in Patients with Mild to Moderate COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021 Feb 16;325(7):632-644.

33. Mahase E. Covid-19: FDA authorises neutralising antibody bamlanivimab for non-admitted patients. BMJ. 2020 Nov 11;371:m4362.

34. Liu T, Luo S, Libby P, Shi GP. Cathepsin L-selective inhibitors: A potentially promising treatment for COVID-19 patients. Pharmacol Ther 2020 Sep;213:107587.

35. Lim CY, Davis OB, Shin HR, Zhang J, Berdan CA, Jiang X, Counihan JL, Ory DS, Nomura DK, Zoncu R. ER-lysosome contacts enable cholesterol sensing by mTORC1 and drive aberrant growth signalling in Niemann-Pick type C. Nat Cell Biol. 2019 Oct;21(10):1206-1218.

36. Höglinger D, Burgoyne T, Sanchez-Heras E, Hartwig P, Colaco A, Newton J, et al. NPC1 regulates ER contacts with endocytic organelles to mediate cholesterol egress. Nat Commun. 2019 Sep 19;10(1):4276.

37. Khan N, Halcrow PW, Lakpa KL, Afghah Z, Miller NM, Dowdy SF, et al. Two-pore channels regulate Tat endolysosome escape and Tat-mediated HIV-1 LTR transactivation. FASEB J. 2020 Mar;34(3):4147-4162.

38. Zheng Y, Shang J, Yang Y, Liu C, Wan Y, Geng Q, et al. Lysosomal Proteases Are a Determinant of Coronavirus Tropism. J Virol. 2018 Nov 27;92(24):e01504-18.

39. Ballout RA, Sviridov D, Bukrinsky MI, Remaley AT. The lysosome: A potential juncture between SARS-CoV-2 infectivity and Niemann-Pick disease type C, with therapeutic implications. FASEB J. 2020 Jun;34(6):7253-7264.

40. Ou X, Liu Y, Lei X, Li P, Mi D, Ren L, et al. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat Commun. 2020 Mar 27;11(1):1620.

41. Gao J, Tian Z, Yang X. Breakthrough: Chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Biosci Trends. 2020 Mar 16;14(1):72-73.

42. Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell. 2020 Apr 16;181(2):271-280.

43. Yoshimoto F. The proteins of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS CoV-2 or n-COV19), the cause of COVID-19. The Protein Journal. 2020 Jun;39(3):198-216.

44. Semper C, Watanabe N, Savchenko A. Structural characterization of nonstructural protein 1 from SARS-CoV-2. iScience 2021 Jan 22;24(1):101903.

45. Thoms M, Buschauer R, Ameismeier M, Koepke L, Denk T, Hirschenberger M, et al. Structural basis for translational shutdown and immune evasion by the NSP1 protein of SARS-CoV-2. Science, 2020 Sep 4;369(6508):1249-55.

46. Cornillez-Ty C, Liao LJ, Yates J, Kuhn P, Buchmeier M. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nonstructural protein 2 interacts with a host protein complex involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and intracellular signaling. Journal of Virology. 2009 Oct;83(19):10314-8.

47. Davies JP, Almasy KM, McDonald EF, Plate L. Comparative multiplexed interactomics of SARS‑CoV‑2 and homologous coronavirus nonstructural proteins identifies unique and shared host-cell dependencies. ACS Infectious Diseases. 2020 Dec 11;6(12):3174–89.

48. Michalska K, Kim Y, Jedrzejczak R, Maltseva NI, Stols L, Endres M, et al. A crystal structures of SARS-CoV-2 ADP-ribose phosphatase: from the apo form to ligand complexes. IUCrJ. 2020 Jul 17;7 (Pt 5): 814-24.

49. Alhammad YMO, Fehr AR. The viral macrodomain counters host antiviral ADP-ribosylation. Viruses. 2020 Mar 31;12(4):384.

50. Freitas BT, Durie IA, Murray J, Longo JE, Miller HC, Crich D, et al. Characterization and noncovalent inhibition of the deubiquitinase and deISGylase activity of SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease. ACS Infectious. Diseases. 2020 Aug 14;6(8):2099-109.

51. Sakai Y, Kawachi K, Terada Y, Omori H, Matsuura Y, Kamitani W. Two-amino acids change in the NSP4 of SARS coronavirus abolishes viral replication. Virology. 2017 Oct;510:165-74.

52. Zhang L, Lin D, Sun X, Curth U, Drosten C, Sauerhering L, et al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science. 2020 Apr 24;368(6489):409–12.

53. Jin Z, Du X, Xu Y, Deng Y, Liu M, Zhao Y, et al. Structure of Mpro from SARS‑CoV‑2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020 Jun;582(7811):289–93.

54. Dai W, Zhang B, Jiang XM, Su H, Li J, Zhao Y, et al. Structure-based design of antiviral drug candidates targeting the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Science. 2020 Apr 22; 368(6497):1331-5.

55. Oerlemans R, Ruiz-Moreno AJ, Cong Y, Velasco-Velazquez MA, Neochoritis CG, Smith J, et al. Repurposing the HCV NS3-4A protease drug boceprevir as COVID-19 therapeutics. RSC Medicinal Chemistry. 2021;12:370-9.

56. Qiao J, Li YS, Zeng R, Liu FL, Luo RH, Huang C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors with antiviral activity in a transgenic mouse model. Science. 2021 Mar 26;371(6536):1374-8.

57. Fu L, Ye F, Feng Y, Yu F, Wang Q, Wu Y, et al. Both boceprevir and GC376 efficaciously inhibit SARS-CoV-2 by targeting its main protease. Nature Communications. 2020 Sep 4;11(1):4417.

58. Kneller DW, Phillips G, O’Neill HM, Jedrzejczak R, Stols L, Langan P, et al. Structural plasticity of SARS-CoV-2 3CL M proactive site cavity revealed by room temperature X-ray crystallography. Nature Communications. 2020 Jun 24;11(1):3202.

59. Ziebuhr J, Snijder EJ, Gorbalenya AE. Virus encoded proteinases and proteolytic processing in the Nidovirales. The Journal of General Virology. 2020 Apr;81(Pt 4):853-79.

60. Zhang C, Zheng W, Huang X, Bell EW, Zhou X, Zhang Y. Protein structure and sequence reanalysis of 2019-nCoV Genome refutes snakes as its intermediate host and the unique similarity between its spike protein insertions and HIV-1. Journal of Proteome Research. 2020 Apr 3;19(4):1351-60.

61. Kirchdoerfer RN, Ward AB. Structure of the SARS-CoV NSP12 polymerase bound to NSP7 and NSP8 co-factors. Nature Communications. 2019 May 28;10(1):2342.

62. Konkolova E, Klima M, Nencka R, Boura E. Structural analysis of the putative SARS-CoV-2 primase complex. Journal of Structural Biology. 2020 Aug 1;211(2):107548.

63. Littler DR, Gully BS, Colson RN, Rossjohn J. Crystal structure of the SARS-CoV-2 non-structural protein 9, NSP9. iScience. 2020 Jul 24;23(7):101258.

64. Buchko GW, Zhou M, Craig JK, Van Voorhis WC, Myler PJ. Backbone chemical shift assignments for the SARS-CoV-2 non-structural protein NSP9: Intermediate (ms - μs) dynamics in the C‑terminal helix at the dimer interface. Biomolecular NMR Assignments. 2021 Apr;15(1):107–16.

65. Rosas-Lemus M, Minasov G, Shuvalova L, Inniss NL, Kiryukhina O, Brunzelle J, et al. High-resolution structures of the SARS-CoV-2 2'- O -methyltransferase reveal strategies for structure-based inhibitor design. Science Signaling. 2020 Sep 29;13(651):eabe1202.

66. Krafcikova P, Silhan J, Nencka R, Boura E. Structural analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 methyltransferase complex involved in RNA cap creation bound to sinefungin. Nature Communications. 2020 Jul 24;11(1):3717.

67. Gadhave K, Kumar P, Kumar A, Bhardwaj T, Garg N, Giri R. Conformational dynamics of NSP11 peptide of SARS-CoV-2 under membrane mimetics and different solvent conditions. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2021 Jun 10;158:105041.

68. Yin W, Mao C, Luan X, Shen DD, Shen Q, Su H, et al. Structural basis for inhibition of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from SARS-CoV-2 by remdesivir. Science. 2020 Jun 26;368(6498):1499-504.

69. Saramago M, Bárria C, Costa VG, Souza CS, Viegas SC, Domingues S, et al. New targets for drug design: importance of nsp14/nsp10 complex formation for the 3′-5′ exoribonucleolytic activity on SARS-CoV-2. The FEBS Journal. 2021 Mar 11.

70. Viswanathan T, Arya S, Chan SH, Qi S, Dai N, Misra A, et al. Structural basis of RNA cap modification by SARS‑CoV‑2. Nature Communications. 2020 Jun 24:11(1):3718.

71. Shen Z, Zhang G, Yang Y, Li M, Yang S, Peng G. Lysine 164 is critical for SARS-CoV-2 NSP1 inhibition of host gene expression. The Journal of General Virology. 2020 Jan;102(1):001513.

72. Zhang K, Miorin L, Makio T, Dehghan I, Gao S, Xie Y, et al. Nsp1 protein of SARS-CoV-2 disrupts the mRNA export machinery to inhibit host gene expression. Science Advances. 2021 Feb 5;7(6):eabe7386.

73. Matsuyama T, Kubli SP, Yoshinaga SK, Pfeffer K, Mak TW. An aberrant STAT pathway is central to COVID-19. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2020 Dec;27(12):3209-25.

74. Chowdhury N, Bagchi A. Identification of the binding interactions of some novel antiviral compounds against NSP1 protein from SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) through high throughput screening. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics. 2021 Feb 22:1-8.

75. Gordon DE, Jang GM, Bouhaddou M, Xu J, Obernier K, White KM, et al. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature. 2020 Jul;583(7816):459-68:

76. Angeletti S, Benvenuto D, Bianchi M, Giovanetti M, Pascarella S, Ciccozzi M. COVID‑2019: The role of the nsp2 and nsp3 in its pathogenesis. Journal of Medical Virology. 2020 Jun;92(6):584–88.

77. Hosseini Rad Sm A, McLellan AD. Implications of SARS-CoV-2 mutations for genomic RNA structure and host microRNA targeting. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020 Jul 7;21(13):4807.

78. Barretto N, Jukneliene D, Ratia K, Chen Z, Mesecar AD, Baker SC. The papain-like protease of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus has deubiquitinating activity. Journal of Virology. 2005 Dec;79(24): 15189-98.

79. Rut W, Lv Z, Zmudzinski M, Patchett S, Nayak D, Snipas SJ, et al. Activity profiling and crystal structures of inhibitor-bound SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease: A framework for anti-COVID-19 drug design. Science Advances. 2020 Oct 16;6(42):eabd4596.

80. Sicari D, Chatziioannou A, Koutsandreas T, Sitia R, Chevet E. Role of the early secretory pathway in SARS-CoV-2 infection. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2020 Sep 7;219(9):e202006005.

81. Ma C, Sacco MD, Hurst B, Townsend JA, Hu Y, Szeto T, et al. Boceprevir, GC-376, and calpain inhibitors II, XII inhibit SARS-CoV-2 viral replication by targeting the viral main protease. Cell Research. 2020 Aug; 30(8):678-92.

82. Mahdi M, Mótyán JA, Szojka ZI, Golda M, Miczi M, Tőzsér J. Analysis of the Efficacy of HIV Protease Inhibitors Against SARS-Cov-2′S Main Protease. Virology Journal. 2020 Nov 26;17(1):190.

83. Braz HLB, Silveira JAM, Marinho AD, de Moraes MEA, Moraes Filho MO, Monteiro HAS, et al. In silico study of azithromycin, chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine and their potential mechanisms of action against SARS-CoV-2 infection. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2020 Sep;56(3):106119.

84. Khan SA, Zia K, Ashraf S, Uddin R, Ul-Haq Z. Identification of chymotrypsin-like protease inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 via integrated computational approach. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics. 2020 Apr;39(7):2607-16.

85. Wu C, Liu Y, Yang Y, Zhang P, Zhong W, Wang Y, et al. Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020 May;10(5):766-788.

86. Patil R, Chikhale R, Khanal P, Gurav N, Ayyanar M, Sinha S, et al. Computational and network pharmacology analysis of bioflavonoids as possible natural antiviral compounds in COVID-19. Inform Med Unlocked. 2021;22:100504.

87. Kar P, Sharma NR, Singh B, Sen A, Roy A. Natural compounds from Clerodendrum spp. as possible therapeutic candidates against SARS-CoV-2: An in silico investigation. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021 Aug;39(13):4774-4785.

88. Pandey P, Prasad K, Prakash A, Kumar V. Insights into the biased activity of dextromethorphan and haloperidol towards SARS-CoV-2 NSP6: in silico binding mechanistic analysis. Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2020 Dec;98(12):1659-73.

89. Gastaminza P, Whitten-Bauer C, Chisari FV. Unbiased probing of the entire hepatitis C virus life cycle identifies clinical compounds that target multiple aspects of the infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010 Jan 5;107(1):291-6.

90. Johansen LM, DeWald L.E, Shoemaker CJ, Hoffstrom BG, Lear-Rooney CM, Stossel A, et al. A screen of approved drugs and molecular probes identifies therapeutics with anti-Ebola virus activity. Science Translational Medicine. 2015 Jun 3;7(290), 290ra89.

91. Vela JM. Repurposing Sigma-1 receptor ligands for COVID-19 therapy? Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2020 Nov 9;11:582310.

92. Xia H, Cao Z, Xie X, Zhang X, Chen JY, Wang H, et al. Evasion of type I interferon by SARS-CoV-2. Cell Reports. 2020 Oct 6;33(1):108234.

93. Courouble VV, Dey SK, Yadav R, Timm J, Harrison JJEK, Ruiz FX, et al. Resolving the dynamic motions of SARS-CoV-2 NSP7 and NSP8 proteins using structural proteomics. BioRxiv. 2021 Mar 6.

94. Zhang CH, Chen YP, Li L, Yang Y, He J, Chen C. et al. Structural basis for the multimerization of nonstructural protein NSP9 from SARS-CoV-2. Molecular Biomedicine. 2020 Aug 20:5.

95. Salman S, Shah FH, Idrees J, Idrees F, Velagala S, Ali J, et al. Virtual screening of immunomodulatory medicinal compounds as promising anti-SARS-COV-2 inhibitors. Future Virology. 2020 May;15(5):267-75.

96. Chandel V, Sharma PP, Raj S, Choudhari R, Rathi B, Kumar D. Structure-based drug repurposing for targeting NSP9 replicase and spike proteins of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics. 2020 Aug 24:1-14.

97. Junior NN, Santos IA, Meireles BA, Nicolau MSP, Lapa IR, Aguiar RS, et al. In silico evaluation of lapachol derivatives binding to the Nsp9 of SARS-CoV-2. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics. 2021 Jan 22: 1-15.

98. Lin S, Chen H, Ye F, Chen Z, Yang F, Zheng Y, et al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 nsp10/nsp16 2'-O-methylase and its implication on antiviral drug design. Signal Transduction and Target Therapy. 2020 Jul 29:5 (1):131.

99. Yan S, Wu G. Potential 3-chymotrypsin-like cysteine protease cleavage sites in the coronavirus polyproteins pp1a and pp1ab and their possible relevance to COVID-19 vaccine and drug development. FASEB Journal. 2021 May;35(5):e21573.

100. Kaushal N, Gupta Y, Goyal M, Khaiboullina SF, Baranwal M, Verma SC. Mutational frequencies of SARS-CoV-2 genome during the beginning months of the outbreak in USA. Pathogens. 2020 Jul 13;9(7):565.

101. Peng Q, Peng R, Yuan B, Zhao J, Wang M, Wang X, et al. Structural and biochemical characterization of the NSP12-NSP7-NSP8 core polymerase complex from SARS-CoV-2. Cell Reports. 2020 Jun 16;31(11):107774.

102. Gordon CJ, Tchesnokov EP, Woolner E, Perry JK, Feng JY, Porter DP, et al. Remdesivir is a direct-acting antiviral that inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 with high potency. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2020 May 15;295(20):6785-97.

103. Shu T, Huang M, Wu D, Ren Y, Zhang X, Han Y, et al. SARS-coronavirus-2 NSP13 possesses NTPase and RNA helicase activities that can be inhibited by bismuth salts. Virological Sinica. 2020 Jun:35(3):321-9.

104. Mirza MU, Froeyen MJ. Structural elucidation of SARS-CoV-2 vital proteins: Computational methods reveal potential drug candidates against main protease, Nsp12 polymerase and Nsp13 helicase. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis. 2020 Aug;10(4):320-8.

105. White MA, Lin W, Cheng X. Discovery of COVID-19 inhibitors targeting the SARS-CoV-2 Nsp13 helicase. The Journal of Physical Chemistry letters. 2020 Nov 5;11(21):9144-51.

106. Adedeji AO, Singh K, Kassim A, Coleman CM, Elliott R, Weiss SR, et al. Evaluation of SSYA10-001 as a replication inhibitor of severe acute respiratory syndrome, mouse hepatitis, and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronaviruses. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2014 Aug;58(8):4894-8.

107. Selvaraj C, Dinesh DC, Panwar U, Abhirami R, Boura E, Singh SK. Structure-based virtual screening and molecular dynamics simulation of SARS-CoV-2 guanine-N7 methyltransferase (nsp14) for identifying antiviral inhibitors against COVID-19. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics. 2020 Jun 22:1-12.

108. Ahmed-Belkacem R, Sutto-Ortiz P, Guiraud M, Canard B, Vasseur JJ, Decroly E, et al. Synthesis of adenine dinucleosides SAM analogs as specific inhibitors of SARS-CoV NSP14 RNA cap guanine-N7-methyltransferase. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2020 Sep 1;201:112557.

109. Liu C, Zhu X, Lu Y, Zhang X, Jia X, Yang T. Potential treatment of Chinese and Western Medicine targeting NSP14 of SARS-CoV-2. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis. 2020 Sep 7.

110. Khater S, Dasgupta N, Das G. Combining SARS-CoV-2 proofreading exonuclease and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitors as a strategy to combat COVID-19: A high-throughput in silico screen. OSF Preprints. 2020 Jun 24.

111. Narayanana N, Naira DT. Ritonavir may inhibit exoribonuclease activity of NSP14 from the SARS CoV 2 virus and potentiate the activity of chain terminating drugs. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2021 Jan 31;168:272-8.

112. Devkota K, Schapira M, Perveen S, Yazdi AK, Li F, Chau I, et al. Probing the SAM binding site of SARS-CoV-2 NSP14 in vitro using SAM competitive inhibitors guides developing selective bi-substrate inhibitors. BioRxiv. 2021 Feb 19.

113. Pearson LA, Green CJ, Lin D, Petit AP, Gray DW, Cowling VH, et al. Development of a high-throughput screening assay to identify inhibitors of the SARS-CoV-2 guanine-N7-methyltransferase using RapidFire mass spectrometry. SLAS Discovery. 2021 Jul;26(6):749-56.

114. Bhardwaj K, Sun J, Holzenburg A, Guarino LA, Kao CC. RNA recognition and cleavage by the SARS coronavirus endoribonuclease. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2006 Aug 11;361(2):243-56.

115. Deng X, Hackbart M, Mettelman R, O’Brien A, Mielech A, Yi G, et al. Coronavirus nonstructural protein 15 mediates evasion of dsRNA sensors and limits apoptosis in macrophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2017 May 23;114(21):E4251–60.

116. Hackbart M, Deng X, Baker SC. Coronavirus endoribonuclease targets viral polyuridine sequences to evade activating host sensors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2020 Apr 7;117(14):8094–103.

117. Pillon MC, Frazier MN, Dillard LB, Williams JG, Kocaman S, Krahn JM, et al. Cryo-EM structures of the SARS-CoV-2 endoribonuclease NSP15. bioRxiv. 2020 Aug 11.

118. Kim Y, Wower J, Maltseva N, Chang C, Jedrzejczak R, Wilamowski M, et al. Tipiracil binds to uridine site and inhibits NSP15 endoribonuclease NendoU from SARS-CoV-2. Communications Biology. 2021 Feb 9;4(1):193.

119. Naik B, Gupta N, Ojha R, Singh S, Prajapati VK, Prusty D. High throughput virtual screening reveals SARS-CoV-2 multi-target binding natural compounds to lead instant therapy for COVID-19 treatment. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2020 Oct 1;160:1-17.

120. Sk MF, Jonniya NA, Roy R, Poddar S, Kar P. Computational investigation of structural dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 Methyltransferase-stimulatory factor heterodimer NSP16/NSP10 bound to the cofactor SAM. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences. 2020 Nov 24;7:590165.

121. Jiang Y, Liu L, Manning M, Bonahoom M, Lotvola A, Yang Z. Repurposing therapeutics to identify novel inhibitors targeting 2′-O-ribose methyltransferase NSP16 of SARS-CoV-2. ChemRxiv. 2020 May 11.

122. Nguyen HL, Thai NQ, Truong DT, Li MS. Remdesivir Strongly Binds to Both RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase and Main Protease of SARS-CoV-2: Evidence from Molecular Simulations. J Phys Chem B. 2020 Dec 17;124(50):11337-11348.