Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic presents unprecedented challenges for anesthesia professionals and their surgical patients. Beyond managing infection risk, positive COVID-19 surgical patients add additional challenges to their perioperative care, where its perioperative risk are superimposed onto an already baseline anesthesia risk in real-time with an unknown and unpredictable fashion. Recent evidence suggests that surgical procedures for both current and recovered COVID-19 patients are associated with elevated morbidity and mortality. These risks must be well managed. However, the anesthetic risk aside from transmission is yet to be fully understood. As such, fast dissemination, and effective implementation of the latest evidence into practice is essential. However, the traditional “knowledge to action gap” of 17 years or more in healthcare is a hinderance [1,2]. We herein designed and implemented a new but simple perioperative criterion for previous COVID-19 patients based on the principle of the perioperative surgical home (PSH) within the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). This platform allows us to implement and/or de-implement components of the PSH clinical pathway with ease in accordance with the fast-evolving COVID-19 pandemic knowledge and experience base.

Keywords

COVID-19, Surgery, Evaluation, Implementation, Perioperative surgical Home, Anesthesiology, Sequalae

Core Tip:

With COVID-19 pandemic, multiple physiological systems will have varying long-term effects and sequalae. As such, perioperative considerations and its implementation for the anesthesiologist will be of prime importance. Depending on the symptoms, specific management is prudent. It behooves the anesthesiologists to complete a covid-19 specific review of symptoms as these patients are at higher risk of long-term pulmonary emboli, respiratory fragility, cardiac arrhythmias, hepatic and renal dysfunction, and a generalized inflammatory state. A rapid implementation process through the CFIR for a PSH pathways is simple but crucial to the new post-pandemic healthcare system.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic challenges all aspects of human life physically, psychologically, socially, and further. At the time of this paper’s submission, over 120 million people have confirmed infections, and over 2.5 million people lost their lives [3,4]. While the direct cost related to the acute treatment of Covid-19 patients is enormous, the emerging evidence suggests recovered COVID-19 patients are still in need of continued medical care, which may or may not be directly linked to the acute or chronic sequala of COVID-19 or their synergistic effect. Currently, there are over 80 million recovered COVID-19 patients worldwide, their need for surgical and anesthesia care will grow but optimal and precision perioperative management is yet to be determined based on severity and sequalae of COVID-19 for each individual patient.

Clearly, the treatment of COVID-19 and prevention of its further transmission are of immediate concern and paramount importance. While vaccine efficacy and personal protective equipment (PPE) in preventing transmission are unmistakably important, the significance of COVID-19 RT-PCR screen test in guiding surgical care of recovered or asymptomatic COVID-19 patients is still evolving. The viral kinetic studies suggest that COVID-19 RT-PCR test does not predict COVID-19 transmissibility nor live-viral shedding [5]. Viable virus is rarely detected beyond 9 days of onset of illness symptoms, but Covid RNA shedding as detected by RT-PCR can be persistent ranging from average of 17 days in the upper airway, 14.6 days in the lower respiratory tract, 17.2 days in stool and 16.6 days in serum [6,7]. With exceptions in certain cancer and immunocompromised patients, it is now known that transmittable COVID-19 virus is often short lived inside the human body and positive RT-PCR test result without clinical correlation may have limited value aside from complete protection [8,9].

The above uncertainty of the primary or secondary COVID-19 disease sequalae, when coupled with ongoing vaccine immunization efforts, presents a uniquely difficult challenge to anesthesiologists. The challenges are perpetuated by incomplete knowledge, evidence and experience as the disease is still new, mutating, interacting with treatments, and evolving. On the other hand, the traditional 17-year “knowledge to action gap” is incompatible with the current clinical needs, where fast dissemination of emerging evidence and introduction of frequent new changes are required in dynamic manner. Herein, we reported a program design based on the principle of perioperative surgical home (PSH) and an implementation process based on the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)—a pragmatic framework designed to translate information into real-world application. We highlight the need for a consistent framework where the program or components of the program are subject to frequent modification, upgrade, and implementation in the evolving pandemic.

Practice Environment

As the largest integrated delivery system (IDS) in the United States, Kaiser Permanente (KP) is composed of 3 distinct yet fully integrated entities: Kaiser Foundation Health Plan (insurance), Kaiser Foundation Hospitals (hospitals), and Permanente Medical Groups (physicians). Because these 3 entities are bound together financially and operationally, it is vital for each of them to align with others to provide the highest possible quality of care consistently at an affordable cost, which is critically important for the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic today. Kaiser Permanente Baldwin Park (KPBP) Medical Center is one of 13 KP medical centers located in Southern California. KP Baldwin Park is in the greater Los Angeles area and serves a community of approximately 300,000 members, to which we managed one of largest density of COVID-19 population. As of today, we managed over 31,716 COVID-19 positive patients as of March 29, 2021 both on an inpatients or outpatient basis. Before COVID, KPBP managed approximately 75,000 emergency department visits, 13,000 hospital admissions, >3,500 inpatients surgery, and 9,000 outpatient surgeries annually. The department of anesthesiology and perioperative medicine is a physician only group practice with physician assistant (PA) support for our dedicated anesthesia preoperative clinic.

PSH Protocol Design

By using the development of KPBP guidelines for post COVID-19 surgical patients as an example (Figure 1), we illustrated here the steps and process on the development of perioperative guidelines for our hospital. In our Risk-Recovery Assessment tool (Figure 1), the primary focus was on creating a practical guide that could be used by all perioperative team members regardless of their COVID-19 knowledge and professional background. This includes staff and implementation leaders amongst schedulers, surgeons, anesthesiologists, perioperative staff, and administrators. With expedient implementation and wider adoption as an objective, we opted for a simple, user-friendly approach to stratifying these patients. For more complicated cases or case scenarios that did not fit guidelines, we depended on our champions, integral members of our design team, in each respective specialty for customized expert care.

Figure 1: Perioperative management for previously COVID+ patients.

Preoperative phase

For urgent and emergent surgery, the focus is on balancing transmissibility risk, sequalae risk and associated surgical risk. Given the tremendous overlap in illness severity, symptom profile, and confounding factors such as pre-existing comorbidities for elective surgery, the focus was on typical recovery times for upper respiratory illnesses, pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, myocardial infarctions, and cerebrovascular accidents. We proposed a 2-week delay of urgent surgery following any Covid vaccination (single dose, 1st dose or 2nd dose). This would allow for full benefit of the recently administered vaccination dose and reduce the potential of immunomodulation from perioperative steroid use, NSAID use, or a surgical stress response. Given the innumerable variables, we split the evaluation into a universal evaluation and an individualized evaluation that should be guided by an in-depth directed system review as per Figure 1 and directed detailed management and work-up.

Intraoperative phase

The physiologic effects of COVID-19 lead to a cascade of different complications that could manifest at any time during their illness or after their illness, particularly pulmonary fibrosis and pneumothorax. Realizing that it would be impossible to encompass the complexity and dynamics of all sequelae in a user-friendly manner, the chart serves as a checklist through which one can prepare for possible perioperative complications and maintain a higher level of vigilance. Although simple and basic, we intend for this guide to aid our clinical decision making rather than replace it, such that we continue to tailor our care for these patients on a case-by-case basis.

Postoperative phase

Our immediate concerns for COVID patients in the postoperative phase are adequate ventilation and oxygenation. Critical illness myopathy leads to a concern for muscle relaxant dosing and respiratory muscle weakness. It is also worrisome for the potential existence of V-Q mismatch due to pulmonary fibrosis, central and peripheral causes of apnea and other elevated risk for comorbidities and complications. As well as overall pulmonary tissue frailty. While oxygenation measurement by continuous pulse oximetry is routine, ventilation measurements are not common aside from respiratory rates. Given that inadequate ventilation often precedes inadequate oxygenation, implementation of noninvasive respiratory monitoring via Exspiron 1xi (Respiratory Motion Inc, Boston, MA), which provides tidal volumes (Tv), minute ventilation (MV), accurate respiratory rate (RR), and a percent of MV calculated with measured MV over patient’s ideal minute ventilation based on height, weight and gender (Predictive Minute ventilation – MVpred), was able to give us an early warning sign. ExSpiron was adopted through our previously validated protocol for postoperative obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and a protocol for COVID-19 triaging (Figure 2) [10-12].

Figure 2: COVID-19 protocol.

PSH protocol implementation

Implementation framework: This was a framework-driven implementation by following a modified CFIR pathway [13]. This is a simultaneous bottom up and top-down approach previously described by our team [14,15]. The bottom up aspect was characterized by the proactive engagement of anesthesiologists who actively managed intensive care unit and perioperative COVID-19 patients. These strategically placed providers identified care gaps for the patients, set up goals for improvement and jointly formulated a plan of approach. The top-down methods include the early engagement of senior leaders in our hospital, key stockholders’ discussions and development of policy and procedures which was called the OR committee meeting.

Dynamic modelling: This modeling allowed us to analyze multiple, simultaneous and complex interactions over time [16]. This model addresses the dynamic nature between the COVID-19 pandemic, PPE strategies, vaccine rollout, and perioperative care of the surgical patients. KP Health connect is a well-established EMR that was an integral in-patient evaluation and was previously validated.

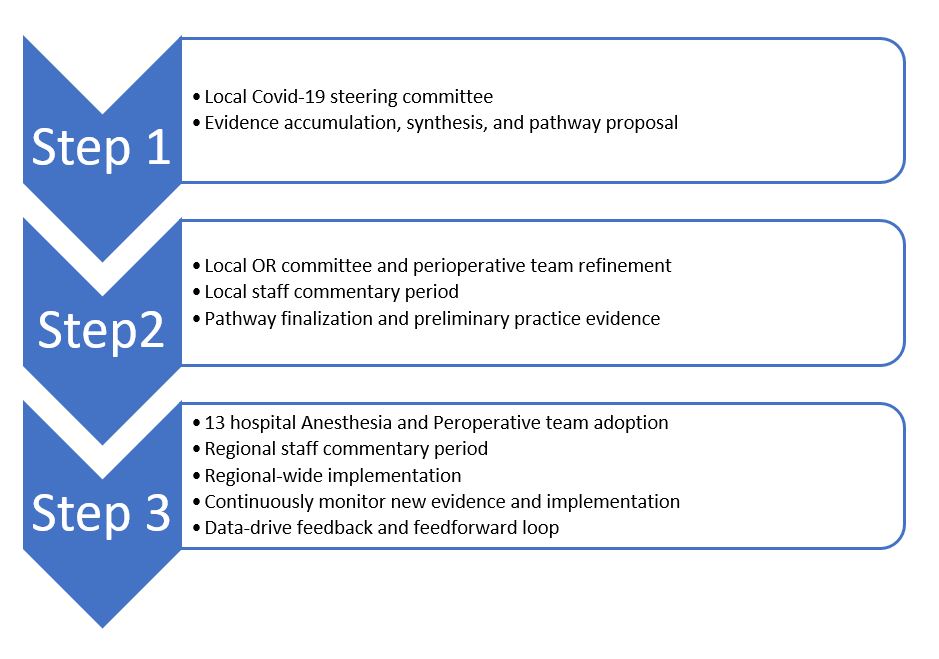

Implementation process (Figure 3): The bottom-up grassroot work was started with the realization that there was a vacant need for individualized surgical care for the increasing population of previously COVID-19 patients.

Figure 3: Step implementation process buttom up top down.

First a steering committee was formed to gather evidence, identify practice gaps, and design pathways. We designed our initial guideline and initial pathway in October 2020 based on the limited scientific evidence coupled with a vast ICU practice experience gained from independent ICU care for COVID-19 patients.

Secondly, we formulated the guideline with frequent and continued improvements biweekly, which was materialized through a unique implementation process. The burden of implementation was complex and had a steep adoption and learning curve. However, all stake holders soon became accustomed to the frequent updates.

Finally, after initial implementation success in our local hospital, the value of this guideline was quickly recognized and spread amongst 13 of our hospitals by our regional perioperative leadership. This top down approach enabled the quick spread of new pathways and understanding across KP Southern California region which reached out to all surgeons, anesthesiologists, certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs), surgery schedulers, and perioperative leaders. At the time of the publication of this paper, implementation data and impact of its applications are accumulating.

Discussion

Over 40 million, elective surgeries have been impacted by the pandemic and that number is growing rapidly [17,18]. The decision making to provide the right care at the right time for post COVID-19 surgical patients continues to evolve. Under current conditions, how to conduct “evidence-based practice” when evidence is limited, and how to overcome “knowledge to action gap” when evidence emerges is an overwhelming undertaking for our already stressed perioperative services. While delivering safe, high quality, and personalized perioperative care remains our goal. We sought an innovative pathway that can fulfill our need for current pandemic and future clinical practice not by rigid guidelines but dynamic and continued implementation.

We introduced a guideline for post COVID-19 surgical patients based on the principle of the Perioperative Surgical Home (PSH). Although different from our previous reported PSH program [14,15], this new version was based on the need of a consistent implementation platform that can simultaneously accommodate through frequent updates or component changes. This novel workflow can effectively facilitate both feedback and feedforward mechanism for a robust dynamic PSH program. Our PSH protocol was first originated from the members of a multidisciplinary surgical team with combined expertise in surgery, anesthesia, hospital medicine and ICU COVID-19 care. The team members not only kept pace with the expanding COVID-19 knowledge but was also responsible for disseminating latest scientific evidence and subsequently designed the practical clinical pathways. After approval by the steering committee, senior leadership and chief of service, the implementation process was initiated in synchronization with all perioperative services including surgery schedulers, surgeons, anesthesiologist, perioperative nursing and other ancillary services such as our laboratory and sterile processing department. One of the unique features of this pathway was that not only did the design team contribute to the original idea and pathways, they also functioned as the implementation champions in their respective specialties where their knowledge and expertise can be fully leveraged. This feature allowed us to formulate a practical and actionable plan quickly without the consideration of completeness due to the ever-changing nature of the pandemic. Due to this historical pandemic, this bottom up and top down approach allowed us to meet the unprecedented and monumental challenges in real time and improve our surgical care in a more precise, productive, and efficient fashion. Moreover, this process instantly brought our leaders and frontline worker together as a team to conquer the common threats of COVID-19. However, our readers should interpret the result about our current PSH program with caution because of incomplete knowledge about optimal COVID preoperative optimization and postoperative functional recovery. Our result demonstrated the efficacy of PSH principle in fulfilling the vacant need for rapid implementation and de-implementation due to the developing nature of COVID pandemic.

We designed our program with the realization that post COVID-19 surgical patients are different from the non-COVID patient in many ways.

1. Multiorgan and multisystem disease - Potential unrecognized functional compromise of vital organs such as brain, heart, lung, liver and kidney and systems such as the neuromuscular.

2. Exposure- History of extensive exposure to sedatives and narcotics during their hospital stay especially ICU stays.

3. Unknown - Unknown changes of stress response and immune reaction due to surgery and anesthesia.

Even after initial COVID-19 infection and hospitalization, our understanding continues to evolve about this multisystem immune and partially auto-immune disease. Available evidence suggests that even mild or non-symptomatic infection may carry some long-term sequelae [19]. Currently, there are more than 50 identified long-term effects of COVID-19. Of hospital discharged patients, 76% continue to experience symptoms which was dominated by fatigue, muscle weakness, sleep disturbance, anxiety and depression. In these “long haulers” as defined by Dr. Fauci or Post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), demonstrated 52% abnormalities in lung CT and functional test (LEFT) including ground glass opacity, irregular lines, consolidations and fibrosis [20]. Other organ abnormalities such as cardiovascular, renal, liver and neurocardiac abnormalities are also common [21]. This fluid nature of COVID-19 influenced our design philosophy: to form a reliable solid implementation framework that can accommodate the frequent component changes.

Even though our intention focused on the implementation of a dynamic COVID-19 PSH program, lack of clinical outcome data is an obvious limitation. Considering the needed for frequent updates for the pathway or pathway components during the current COVID-19 pandemic, our outcome data can neither be easily interpreted nor can it be the main objective of this report. The framework we used to create our pathways comes from the field of implementation research which arose to study barriers to bridging the gap between knowledge and clinical care and therefore poised to help solve this time lag experienced in medicine to implement positive changes based on research. This framework, the built-in feedback (bottom-up) and feedforward (top-down) mechanisms as well as our exciting implementation team are the pivotal essentials. We believe the development and optimization of this science-based approach will have implications long after this pandemic and have wider implications for improving overall anesthesiology and perioperative medicine in the future.

Author Contributions

Shah N, Chung E, Chunyuan Qiu conceived the idea for the manuscript; All authors reviewed the literature and draft, and provided critical review of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g., consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Funding Statement

There are no disclosures for any external sources of funding for this manuscript.

References

2. Morris ZS, Wooding S, Grant J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: understanding time lags in translational research. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2011 Dec;104(12):510-20.

3. Prescott HC. Outcomes for patients following hospitalization for COVID-19. JAMA. 2021 Apr 20;325(15):1511-2.

4. World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. 26 March 2021. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/ Cited 26 March 2021.

5. Sun K, Wang W, Gao L, Wang Y, Luo K, Ren L, et al. Transmission heterogeneities, kinetics, and controllability of SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2021 Jan 15;371(6526).

6. Perera RA, Tso E, Tsang OT, Tsang DN, Fung K, Leung YW, et al. SARS-CoV-2 virus culture and subgenomic RNA for respiratory specimens from patients with mild coronavirus disease. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2020 Nov;26(11):2701.

7. Cevik M, Tate M, Lloyd O, Maraolo AE, Schafers J, Ho A. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV viral load dynamics, duration of viral shedding, and infectiousness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Microbe. 2020 Nov 19.

8. Avanzato VA, Matson MJ, Seifert SN, Pryce R, Williamson BN, Anzick SL, et al. Case study: prolonged infectious SARS-CoV-2 shedding from an asymptomatic immunocompromised individual with cancer. Cell. 2020 Dec 23;183(7):1901-12.

9. Choi B, Choudhary MC, Regan J, Sparks JA, Padera RF, Qiu X, et al. Persistence and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in an immunocompromised host. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020 Dec 3;383(23):2291-3.

10. Qiu C, Cheng E, Winnick SR, Nguyen VT, Hou FC, Yen SS, et al. Respiratory Volume Monitoring in the Perioperative Setting Across Multiple Centers. Respiratory Care. 2020 Apr 1;65(4):482-91.

11. Desai VN, Shah DH, Cohen JM, Winnick SR, Gonzalo C, Naughton J, et al. Triaging Covid-19 Patients in The Emergency Room Using A Respiratory Volume Monitor. Proceedings of the American Society of Anesthesiology Conference; 2020 Oct 2-5

12. Desai VN, Shah DH, Mobassery H, Winnick SR, Thomas S, Custodio G, et al. Early Prediction of Covid-19 Patient Deterioration Utilizing Non-Invasive Respiratory Volume Monitoring. Proceedings of the American Society of Anesthesiology Conference; 2020 Oct 2-5; Washington DC

13. Saluja S, Silverstein A, Mukhopadhyay S, Lin Y, Raykar N, Keshavjee S, et al. Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to implement and evaluate national surgical planning. BMJ Global Health. 2017 Jul 1;2(2):e000269.

14. Qiu C, Cannesson M, Morkos A, Nguyen VT, LaPlace D, Trivedi NS, et al. Practice and outcomes of the perioperative surgical home in a California integrated delivery system. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2016 Sep 1;123(3):597-606.

15. Qiu C, Rinehart J, Nguyen VT, Cannesson M, Morkos A, LaPlace D, et al. An ambulatory surgery perioperative surgical home in Kaiser Permanente settings: practice and outcomes. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2017 Mar 1;124(3):768-74.

16. Peters DH. The application of systems thinking in health: why use systems thinking?. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2014 Dec;12(1):1-6.

17. "Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans." Journal of British Surgery 107, no. 11 (2020): 1440-1449.

18. Ljungqvist O, Nelson G, Demartines N. The post COVID-19 surgical backlog: Now is the time to implement enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS). World Journal of Surgery. 2020 Oct;44(10):3197-8.

19. Lopez-Leon S, Wegman-Ostrosky T, Perelman C, Sepulveda R, Rebolledo PA, Cuapio A, et al. More than 50 Long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Available at SSRN 3769978. 2021 Jan 1.

20. Truffaut L, Demey L, Bruyneel AV, Roman A, Alard S, De Vos N, et al. Post-discharge critical COVID-19 lung function related to severity of radiologic lung involvement at admission. Respiratory Research. 2021 Dec;22(1):1-6.

21. Lechowicz K, Drożdżal S, Machaj F, Rosik J, Szostak B, Zegan-Barańska M, et al. COVID-19: the potential treatment of pulmonary fibrosis associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Journal of Cinical Medicine. 2020 Jun;9(6):1917.