Abstract

Pain is one of the most common symptoms experienced by patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. Adequate pain management is critical to the well-being and overall recovery of these patients. This study aimed to evaluate the effect of preoperative in-person pain education on the pain severity experienced by patients undergoing CABG surgery in Rajaie Cardiovascular, Medical and Research Center in Tehran in 2022. In this quasi-experimental study, 72 patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery were selected and randomly divided into intervention (n=36) and control (n=36) groups. The intervention group received pain control education for 20 to 30 minutes and the control group received only standard preoperative care. The pain severity was measured using the numerical rating scale (NRS) tool at different time points, including before the operation, as well as 2, 5 and 8 hours after the surgery. Based on the results, preoperative pain education did not show a significant difference in pain severity between the intervention and control groups immediately (2 hours) after endotracheal tube removal (P=0.313). However, a significant difference in the pain severity was observed at 5 hours (P=0.006) and 8 hours (P=0.015) after removal of the endotracheal tube. Moreover, the intervention group had lower pain severity when taking analgesics and higher pain severity when using non-pharmacological methods compared to the control group (P=0.046). Preoperative in-person education may be effective in reducing pain severity in patients undergoing CABG surgery, especially when they are not taking analgesics. These findings demonstrate the importance of implementing preoperative education programs to improve patient outcomes and improve postoperative pain management.

Keywords

Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), Preoperative education, Pain severity, Numerical rating scale (NRS) tool, Postoperative pain management

Introduction

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is a common surgery for treating patients with severe coronary artery disease (CAD). CAD occurs when the coronary arteries, the blood vessels that supply oxygen and nutrients to the heart muscle, become narrowed or blocked by plaque buildup [1]. Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is still the most common cardiac surgery worldwide, representing an annual volume of approximately 200,000 isolated cases in the United States and an average incidence of 62 cases per 100,000 in Western European countries [2]. While this surgery has been proven to be effective in improving the health and quality of life of patients, it is often associated with significant postoperative pain. Reports from international organizations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the American Pain Society (APS), have emphasized the importance of postoperative pain management to improve patient outcomes and satisfaction [3].

The severity of pain experienced by CABG surgery patients can vary depending on several factors. These factors include individual pain thresholds, surgical techniques used, and the patient's overall health status [4]. During and immediately following CABG surgery, patients may experience moderate to severe pain due to the nature of the procedure. To manage the severity of pain, patients are usually given a combination of pain relievers [5]. These can include opiates such as morphine or fentanyl, along with non-opioid pain relievers such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [6,7].

In recent years, there has been a growing focus on minimizing the use of opioids for pain management due to their potential for addiction and other side effects [8]. As a result, multimodal pain management approaches are increasingly being used to decrease opioid dependence [9,10]. Proper pain management is critical to ensuring patient comfort, promoting optimal recovery, and reducing the risk of complications associated with inadequate pain control [11]. It is worth noting that the pain experience of each patient is unique, and the severity of pain can be subjective. Effective communication between patients and health care providers is essential for proper pain assessment and management, as patient comfort and well-being are critical during the recovery period following CABG surgery [12].

Preoperative education has emerged as a potential strategy for reducing pain severity and improving postoperative outcomes. In-person preoperative education refers to the education and information provided to patients before a surgical procedure is performed [13,14]. In the context of patients undergoing CABG surgery, preoperative in-person education can specifically focus on the severity of pain they may experience during and after surgery. CABG surgery is associated with postoperative pain, and providing preoperative education to patients on pain management can be beneficial [15,16].

During an in-person or face-to-face education session nurses or anesthesiologists may explain expected pain severity levels, possible sources of pain, and different pain management techniques [17]. Patients are educated on the importance of accurate and prompt reporting of pain, as well as the potential side effects and risks associated with pain management methods [18]. Additionally, preoperative educational sessions may include information about the expected duration of postoperative pain and anticipated improvements over time [19]. The goal of face-to-face preoperative pain education before CABG surgery is to minimize anxiety, improve patient satisfaction, optimize pain management, and ultimately enhance the overall surgical experience and patient outcomes [20].

There are several numerical scales that are commonly used to measure the severity of pain. Some of the most commonly used include Visual Analog Scale (VAS), Verbal Descriptor Scale (VDS), Faces Pain Scale (FPS), Color Analog Scale (CAS), and Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) [21,22]. Several studies have shown that the NRS has good validity to measure subjective experiences such as pain severity, anxiety level or satisfaction. Additionally, the NRS has good test–retest reliability, meaning that subjects tend to provide consistent ratings when the scale is administered at different time points [21].

Various studies have investigated various strategies to reduce pain severity after CABG surgery, including pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. Several studies have also examined the effect of preoperative interventions on postoperative pain severity in CABG patients [23,24]. These interventions included educating the patient, relaxation techniques, and using multimedia tools. In these studies, the results have been reported in general, and the significant effects of face-to-face education interventions have not been presented. Therefore, there is a research gap regarding the effect of preoperative face-to-face education on pain severity in CABG patients. Previous studies have focused mainly on the preoperative application of multimedia tools. However, the effectiveness of face-to-face education, which allows for personal interaction and appropriate instruction, remains relatively unknown. Given the limited evidence on the effect of preoperative face-to-face education on pain severity in CABG patients, conducting a study to fill this research gap is necessary. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of preoperative in-person education on pain severity in patients undergoing CABG surgery. In this study, the NRS tool was used to measure the pain severity of patients.

Materials and Methods

The aim of the study was to evaluate the effect of preoperative face-to-face education on the pain severity experienced by patients undergoing CABG surgery. In order to conduct this study, the steps mentioned below were carried out.

Study design

This study was a quasi-experimental study, which was conducted in the adult cardiovascular surgery service and Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of a hospital between January and October of 2022 in the Rajaie Cardiovascular, Medical and Research Center. In this study a randomized controlled trial design was employed. The participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention or control group. The intervention group received preoperative face-to-face education, while the control group received standard care.

Participants

The participants of this study were patients undergoing elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery admitted to the surgical department of Rajaie heart center in Tehran in 2022. Participants who met the inclusion criteria were included in the study. In order to conduct this study, 72 patients were selected, of which 36 were male and 36 were female. The participants were between 30 and 65 years old. The studied patients were randomly divided into two intervention (36 patients) and control (36 patients) groups. The patients were admitted to the department one day before surgery. In addition, the patients were evaluated in terms of speech ability, presence of mental illness, and visual and hearing impairment. The patients with chronic pain, visual and hearing impairments, and those with a recent history of opioid use were excluded from the study.

Factors such as history of chronic pain, use of painkillers, social and economic status were also considered when recruiting participants for the study. The participants with a history of chronic pain or those who regularly used painkillers were included in the study, as these factors can influence the severity of pain after surgery. Additionally, the socio-economic status of the participants was taken into account, as these factors can also influence pain intensity. The participants from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds were also included in this study to ensure that the results are applicable to a wide range of individuals.

Sample size

Based on the results of the study by (Tavakoli et al.), the average pain score in the patients of the control group was 3.5 [25]. Considering the median of 3 for the intervention group and using the Mann-Whitney U test and using the G Power 3.1 statistical software, the sample size was calculated at least 36 people in each group (α=0.05, β=0.1).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study have been described in Table 1.

|

Inclusion criteria |

Exclusion criteria |

|

Patients scheduled to undergo coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. |

Patients scheduled for emergency CABG surgery. |

|

Age between 30 and 65 years. |

Age below 30 or above 65 years. |

|

Able to comprehend and communicate in the local language. |

Inability to comprehend or communicate in the local language. |

|

Willing to participate and provide informed consent for the study. |

Refusal to participate or provide informed consent for the study. |

|

No known history of psychiatric disorders. |

History of psychiatric disorders or significant psychological distress.

|

|

No history of previous CABG surgery. |

Previous CABG surgery. |

|

No previous experience with the use of preoperative face-to-face training.

|

Previous experience with preoperative face-to-face training. |

|

There are no contraindications for participating in the study, according to the doctor's diagnosis. |

Contraindications to participating in the study as determined by the attending physician (such as severe cognitive impairment, uncontrolled medical conditions, etc.). |

Sampling method

In this study, simple sampling was used. For this purpose, patients who were admitted to the surgical department of Rajaei Heart Center one day before surgery for elective coronary artery bypass surgery and had all the characteristics of entering the study were considered to participate in the study after obtaining informed consent. Since there were two control and intervention groups in the study, the samples were randomly assigned to the control and intervention groups. In order to prevent the samples from meeting together, the first month of sampling was randomly assigned to the intervention group and then, considering the two-week interval of the second month of sampling, it was assigned to the control group. In the same way, the sampling continued in both groups, and considering the sample size of 76 people, the sampling took 2 months [26].

Intervention and control group

The intervention group received a face-to-face education session conducted by ICU nurses. This educational session was conducted with the aim of educating patients about surgical procedures, post-operative pain management strategies, and relaxation techniques to reduce pain. The session also provided an opportunity for patients to ask questions and address any concerns. Furthermore, the control group received standard care, which included routine preoperative counseling and information provided by ICU nurses.

Outcome measurement

The primary outcome of this study was the severity of pain experienced by patients after surgery, measured using a numerical rating scale (NRS). The NRS is a reliable and valid tool commonly used to assess pain severity on a scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable). The secondary outcome was also the amount of pain medication.

Data collection tools

The method of data collection was self-reporting of patients, file review and obtaining information through a questionnaire. In this study, patient selection questionnaire, demographic characteristics questionnaire, non-pharmaceutical and pharmaceutical methods questionnaire and pain severity measurement questionnaire were used.

The numerical rating scale (NRS) tool

In the study, the pain severity was measured using the numerical rating scale (NRS) tool. The tool is an instrument commonly used in psychometric assessment to measure the intensity or severity of a particular symptom or experience. The NRS usually includes a scale of numbers from 0 to 10, where 0 represents no symptoms and 10 represents the most severe symptoms imaginable. Participants are asked to rate their symptoms or experiences on a scale, usually by choosing a number or pointing to the number on the scale that best represents how they feel. The NRS is often used to assess pain levels but can also be used to assess other symptoms such as anxiety, depression, fatigue, or nausea. The NRS has been found to be a reliable and valid measure of symptom severity, with good sensitivity and responsiveness to changes in symptoms over time. It is a quick and simple tool to administer, which makes it widely used in clinical practice and research settings. The NRS is a valuable tool for assessing symptom severity and monitoring treatment progress in different populations and settings [27].

This questionnaire included information about the pain severity of the patients within 8 hours after being fully awake after the surgery, which was completed in the form of self-reporting by the patients based on the numerical scale of pain intensity. The rating scale of pain intensity was considered as no pain (score 0), mild pain (score 1-3), moderate pain (score 4-6) and severe pain (score 7-10) [28].

The NRS has been shown to have high internal consistency, indicating that the items within the scale are highly correlated with each other. This suggests that the NRS is a reliable tool for measuring subjective experiences. The validity of this questionnaire was calculated by Tavakoli et al. using the Delphi method and its value was reported to be more than 90%. Moreover, the reliability was also confirmed by the same authors and they reported Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.7 [25]. Therefore, the NRS is a valid and reliable tool for evaluating subjective experiences such as pain, anxiety, or satisfaction.

The NRS tool has been shown to have good concurrent validity compared to other pain assessment tools such as visual analogue scales. In addition, the NRS has been shown to have good discriminant validity in differentiating between levels of pain intensity. It has shown good internal consistency and test-retest reliability in previous research. It is a reliable tool for assessing pain intensity over time and has been used in a variety of clinical settings [22].

Study procedure

The study participants were patients undergoing elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery admitted to the surgical departments of Rajaei Heart Hospital in Tehran. The patients who met all the inclusion criteria were included in the study after obtaining informed consent. The participants were divided into intervention and control groups by simple random sampling. The day before surgery, the demographic characteristics questionnaire was completed by the patients of both groups, and then the intervention group received face-to-face education interventions on pain control and management. In this way, during two-way communication for 20 to 30 minutes, explanations that include the reason for performing coronary artery transplant surgery, how to perform coronary artery transplant surgery, conditions after the surgery, explaining the factors that cause pain and uncomfortable symptoms. What happened after the surgery, how to control the pain after the surgery and introducing some non-pharmacological pain relief methods were presented to the patient. Non-pharmacological methods of pain relief included prayer, massage, distraction methods such as mental imagery, and muscle relaxation. Along with the explanations, an educational pamphlet containing a summary of the verbal conversation about pain was given to the patient to remind him of the contents. The patients of the control group did not receive any intervention. After the operation, when the patient was transferred to the cardiac ICU and the effects of the anesthetics, analgesics, and narcotics used in the operating room wore off, and the patient was fully awake and extubated, the pain severity was measured with a 3-hour interval at 2-hour time points. 5 hours and 8 hours were evaluated and measured by NRC questionnaire. This measurement was repeated 3 times for each of the studied patients. In addition, the patient was asked about the non-pharmacological methods used to control pain, and the analgesics received during the days of the patient's hospitalization in the ICU were also checked by checking the patients' files. The patients that had acute complications after surgery, such as bleeding and returning to the operating room or other complications were excluded from the study. In the current study, 38 patients were studied in each of the two groups, and two patients from the intervention group were excluded from the study, one due to post-operative bleeding and returning to the operating room, and the other due to post-operative cardiac arrest. Furthermore, in the control group, two patients were excluded from the study, one due to postoperative bleeding and the other due to long-term intubation (more than 10 hours).

Statistical analysis

The descriptive statistics of mean and standard deviation as well as frequency distribution and percentage were used for general data analysis. In order to accurately analyze the data, chi-square test, independent t-test and regression were used. In addition, for the variables that more than 25% of the cells had a frequency of less than 5, Fisher's exact test was used instead of chi-square test [29]. The data was statistically analyzed using SPSS software version 21 with a significance level of 0.05 and 95% confidence interval.

Ethical considerations

The study adheres to ethical guidelines, ensuring participant confidentiality, voluntary participation, informed consent, and protection of their rights. Moreover, the confidentiality of participant data was ensured, and the study was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and regulations. The study received approval from an ethics committee before initiation.

Results

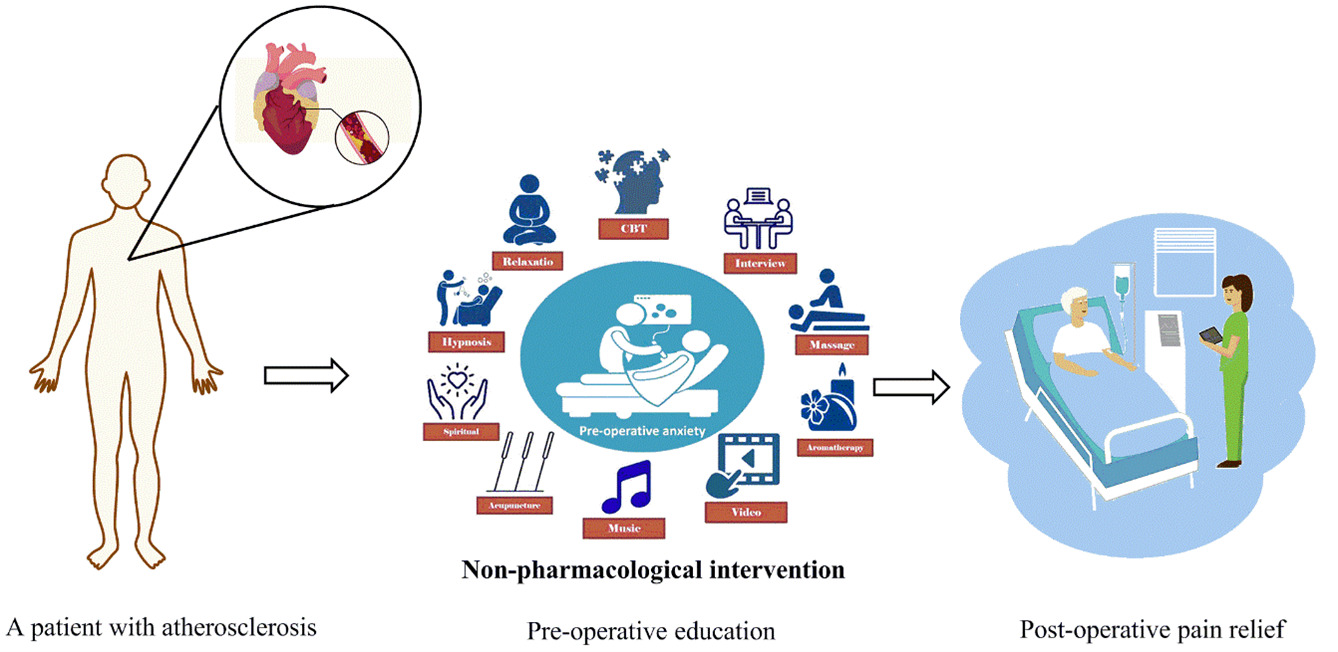

The study investigated the effect of pre-operative in-person education on the pain severity of patients undergoing CABG surgery (Figure 1). In this study, 72 patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery (36 patients in the intervention group and 36 patients in the control group) were evaluated. The demographic characteristics examined in this study included age, gender, place of residence, marital status, education level, and employment status. The characteristics of the participants and a description about their characteristics have been provided in Table 1. Furthermore, the demographic characteristics of both study groups are described in Table 2. In the study, pain severity was reported by patients in 4 rates of no pain, mild, moderate and severe. Two hours after the removal of the endotracheal tube in the intervention group, the frequency of each of 4 rates was 0%, 8.3%, 61.1%, and 30.6%, respectively. In the control group the frequencies were reported as 0%, 5.6%, 52.8%, and 41.7%, respectively (Table 3). Additionally, five hours after the removal of the endotracheal tube in the intervention group, the frequency of each of 4 rates was 2.8%, 55.6%, 41.7%, and 0%, respectively. In the control group the frequencies were 0%, 25%, 58.3%, and 16.7%, respectively (Table 3). Furthermore, eight hours after the removal of the endotracheal tube in the intervention group, the frequency of each of 4 rates was obtained 25%, 55.6%, 19.4%, and 0%, respectively. In the control group the frequencies were 11.1%, 38.9%, 44.4%, and 5.6%, respectively (Table 3). The comparison of pain severity in intervention and control groups with and without taking analgesics in patients has been shown in Table 4. The frequency of pain severity with taking analgesics (narcotic and non-narcotic) in the intervention and control groups was 55.56% and 77.77%, respectively (Table 4). The statistical results indicated a significant difference in the mean score of the pain severity (p=0.046) between the two groups of intervention and control (Table 4). Moreover, the frequency of pain severity without taking analgesics (non-pharmacological methods) in the intervention and control groups was 44.44% and 22.23%, respectively (Table 4).

Figure 1: Schematic illustration of individual preoperative pain education for patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery.

|

Characteristic |

Description |

|

Nationality |

The nationality of the participants who referred to the study hospital were Iranian, and these people had referred to this hospital from different cities of Iran. |

|

Age |

The participants included people of a wide age range, but they were mostly older people, because CABG surgery is usually performed in people with advanced coronary artery disease. The patients were in the age range of 30 to 65 years. |

|

Gender |

The participants included both men and women, as both sexes can develop coronary artery disease and undergo CABG surgery. |

|

Medical history |

The participants were screened for a history of cardiovascular disease such as myocardial infarction (heart attack), angina pectoris, or previous coronary interventions. They underwent diagnostic tests such as angiography to identify blockages in their coronary arteries. |

|

Comorbidities |

The participants were assessed for other comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and smoking. These conditions can contribute to the development or progression of coronary artery disease. |

|

Medications |

The participants were evaluated for taking various medications to manage their cardiovascular conditions, such as antiplatelet agents, cholesterol-lowering medications, beta-blockers, or antihypertensive medications. |

|

Psychological factors |

The participants were assessed for varying levels of anxiety or fear related to the impending surgery and the potential pain associated with it. Their mental health status, including any history of depression or anxiety disorders, may affect the severity of their pain. |

|

Parameter |

Group |

Chi-square test P-value |

|

|

Intervention Number (%) |

Control Number (%) |

||

|

Gender |

|||

|

Man |

10 (27.8) |

13 (36.1) |

0.448 |

|

Woman |

26 (72.2) |

23 (63.9) |

|

|

Location |

|||

|

City |

30 (83.3) |

27 (75) |

0.384 |

|

Village |

6 (16.7) |

9 (25) |

|

|

Marital status |

|||

|

Single |

0 (0) |

1 (2.8) |

|

|

Married |

32 (88.9) |

33 (91.7) |

0.674 |

|

Widow |

4 (11.1) |

2 (5.6) |

|

|

Education level |

|||

|

Illiterate |

2 (5.6) |

2 (5.6) |

|

|

Elementary |

9 (25) |

10 (27.8) |

|

|

Guidance school |

9 (25) |

10 (27.8) |

0.983 |

|

High school |

8 (22.2) |

8 (22.2) |

|

|

University |

8 (22.2) |

6 (16.7) |

|

|

Employment status |

|||

|

Employee |

4 (11.1) |

4 (11.1) |

|

|

Simple worker |

0 (0) |

2 (5.6) |

|

|

Jobless |

12 (33.3) |

10 (27.8) |

0.772 |

|

Retired |

12 (33.3) |

10 (27.8) |

|

|

House keeper |

8 (22.2) |

10 (27.8) |

|

|

Removal time of endotracheal tube |

Pain severity |

Intervention group Number (%) |

Control group Number (%) |

Mann–Whitney U test P-value |

|

Two hours after removing the endotracheal tube |

No pain |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.313 |

|

Mild |

3 (8.3) |

2 (5.6) |

||

|

Moderate |

22 (61.1) |

19 (52.8) |

||

|

Severe |

11 (30.6) |

15 (41.7) |

||

|

Five hours after removing the endotracheal tube |

No pain |

1 (2.8) |

0 (0) |

0.015 |

|

Mild |

20 (55.6) |

9 (25) |

||

|

Moderate |

15 (41.7) |

21 (58.3) |

||

|

Severe |

0 (0) |

6 (16.7) |

||

|

Eight hours after removing the endotracheal tube |

No pain |

9 (25) |

4 (11.1) |

0.006 |

|

Mild |

20 (55.6) |

14 (38.9) |

||

|

Moderate |

7 (19.4) |

16 (44.4) |

||

|

Severe |

0 (0) |

2 (5.6) |

Discussion

This study found that preoperative face-to-face education had a positive effect on reducing pain intensity after CABG surgery, potentially reducing the need for pain medication. The characteristics of the participants in the present study have been described in Table 1. The results demonstrated no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of age, gender, place of residence, marital status, education level, and employment status (p>0.05). It showed that the two groups were comparable in terms of age, gender, place of residence, marital status, education level, and employment status (Table 2).

The preoperative educational intervention in the intervention group included face-to-face training sessions with a special focus on pain management strategies and techniques. The group received information on how to manage pain through non-pharmacological methods such as relaxation techniques, distraction techniques, and deep breathing exercises and guided imagery. The intervention group also received information about the importance of pain management for recovery and was provided with resources for further support. On the other hand, the control group did not receive any specific educational intervention regarding preoperative pain management. They received standard preoperative training on surgical procedure, postoperative care, and anesthesia, but received no additional information or training on pain management strategies.

The results of the study demonstrated that the intervention group had significantly lower pain intensity scores compared to the control group at all stages after the operation. Also, the intervention group had a higher frequency of using non-pharmacological methods for pain management compared to the control group.

In terms of pain severity, the frequency of each category of pain was recorded at different time points after endotracheal tube removal. Two hours after endotracheal tube removal, the intervention group reported a frequency of 0, 8.3, 61.1 and 30.6% for each level of pain. In comparison, the control group reported a frequency of 0, 5.6, 52.8 and 41.7%, respectively (Table 3). However, there was no statistically significant difference in the mean score of pain intensity between the two groups at this time point (p=0.313). Five hours after removal of the endotracheal tube, the intervention group reported a frequency of 2.8, 55.6, 41.7, and 0% for each pain measure. In contrast, the control group reported the frequency of 0, 25, 58.3 and 16.7 percent, respectively (Table 3). The statistical analysis demonstrated a significant difference in the average score of pain severity between the intervention and control groups at this time point (p=0.015). Eight hours after removal of the endotracheal tube, the intervention group reported a frequency of 25, 55.6, 19.4 and 0% respectively for each level of pain. The control group reported 11.1%, 38.9%, 44.4%, and 5.6%, respectively (Table 3). The statistical analysis showed a significant difference in the average score of pain intensity between the two groups at this time point (p=0.006).

Ertürk et al. showed that there was a statistically significant difference between the mean pain intensity scores of the intervention and control groups. The results of their study showed that individual education before open heart surgery had favorable effects on the pain severity of patients after the surgery [30]. Khalid et al. also indicated that in the intervention group that received pre-operative pain education compared to the control group, the severity of postoperative pain decreased significantly and this decrease in pain level was reported to be statistically significant (p<0.001) [31]. As well as Yuksel et al. indicated that patients who received preoperative education had significantly lower pain severity scores and anxiety levels compared to those who did not receive this intervention. The authors concluded that preoperative education is beneficial in alleviating pain severity and anxiety in CABG patients [32]. The results of their study were in accordance with the results obtained from the present study. In another study, Sinderovsky et al. reported that mean cumulative pain scores 48 hours after surgery were lower in those who received the intervention compared to the control group. The results of their study showed that participants who received the intervention had fewer pain improvements compared to the control group. There was no significant difference in the consumption of analgesics in both groups. In their study, postoperative pain severity was reduced in participants who received preoperative pain education compared to the control group [24]. The results of their study were similar to the results obtained from the present study. Similarly, Ng et al. in a review study demonstrated that preoperative education had significant effects on post-intervention anxiety reduction (P=0.02), ICU length of stay (P=0.02) and knowledge improvement (P<0.00001). But it had a small significant effect on reducing postoperative anxiety (P<0.0001), depression (P=0.03) and increasing satisfaction (P=0.04). Their review indicated the feasibility of preoperative education in clinical use to improve the health outcomes of patients undergoing cardiac surgery [13]. The findings of their review confirmed the results of the present study.

Preoperative education can include information about the procedure, what to expect during recovery, and how to better care after surgery. This education can help patients feel more prepared and informed which may lead to better adherence to postoperative care instructions and better outcomes [33]. This training shows that there may be some hesitation or uncertainty about the idea of implementing preoperative training in clinical settings. Further evaluation may be needed to determine the effectiveness of this approach and to address possible barriers to its implementation. Overall, the concept of preoperative education as a tool to improve health outcomes for patients undergoing cardiac surgery deserves further investigation to determine its potential benefits [34].

In the present study, the comparison of the severity of pain in the intervention and control groups with and without taking analgesics was also evaluated (Table 5). The frequency of pain severity with the use of analgesics (narcotic and non-narcotic) in the control group (77.77%) was higher than the intervention group (55.56%). The statistical analysis also indicated a significant difference in the mean pain severity score between the two groups (p=0.046). Similarly, the frequency of pain severity without taking analgesics (non-pharmacological methods) was higher in the intervention group (44.44%) than in the control group (22.23%). In the intervention group, the severity of pain without taking analgesics was higher compared to the control group, and again, the statistical results demonstrated a significant difference (p=<0.001) in the mean pain severity score between the intervention and control groups in this comparison. In a study, Kol et al. reported that the severity of pain, which was defined as sharp, throbbing and excruciating, was higher in the control group than in the intervention group, and the difference between the two groups was statistically significant (p<0.05). In their study, the doses of analgesics used for pain control were compared in both groups. The results of their study showed that the consumption of painkillers in the intervention group was lower than the control group and this difference was statistically significant (p<0.05). It was found that preoperative education reduced the consumption of analgesics in the first 48 hours after surgery [35]. Furthermore, O'donnell et al. revealed that patients who received the preoperative education intervention reported less pain in the first 24 hours after surgery, took less pain medication, and returned to normal activities sooner. In their study, the intervention group used more non-pharmacological pain management methods after the operation compared to the control group patients [36].

|

Pain treatment method |

Intervention group Number (%) |

Control group Number (%) |

Chi-square test P-value |

|

With analgesics (Narcotic and non-narcotic)

|

20 (55.56) |

28 (77.77) |

0.046

0.001>

|

|

Without analgesics

(Non-pharmacological methods)

|

16 (44.44) |

8 (22.23) |

Preoperative education plays an important role in improving patient outcomes and experiences in various surgical procedures. For patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), preoperative education can help manage their pain severity and speed up their overall recovery [37,38]. Pain is a significant concern for patients undergoing CABG surgery, as it is a major surgical procedure that involves opening the chest and manipulating the heart [39]. Preoperative education aims to provide information to patients about surgery, expectations during surgery, and how to effectively manage pain. One of the components of preoperative education is providing information to patients about the surgery itself [40,41]. This includes an explanation of the rationale behind the surgery, its benefits, and potential risks or complications. By giving patients a clear understanding of what will happen during surgery, it can reduce their anxiety and help them mentally prepare for the procedure [42]. Another key aspect of preoperative education is teaching patients pain management strategies. This can include educating them about the different types of pain medications that may be prescribed, how to take them, and any possible side effects [43]. Patients can also be taught non-pharmacological pain management techniques, such as relaxation exercises, breathing techniques, and the use of heat or cold therapy. By empowering patients with knowledge about their pain management options, they can actively participate in their care and feel more in control of their pain [44,45].

In general, the results indicated that preoperative pain education had no significant effect on the reduction of pain intensity immediately after coronary artery bypass grafting. However, the intervention group showed a significant decrease in pain severity at 5 and 8 hours after the removal of the endotracheal tube compared to the control group. In addition, the use of analgesic drugs was associated with greater pain severity in both groups, while non-pharmacological methods were associated with a lower frequency of pain intensity, especially in the intervention group. Preoperative pain management education is an essential component of the overall postoperative care plan. This includes providing patients with comprehensive information and strategies for understanding, predicting and managing pain before surgery. Through this educational intervention, health care professionals can bridge the knowledge gap that often exists between patients and nurses regarding preoperative pain management. By promoting effective communication and shared decision making, patients will have a clear understanding of what to expect before, during, and after surgery, enabling them to actively participate in their pain management.

Several potential confounding variables were identified in this study. These confounding variables included surgical and anesthetic factors that may have influenced the study results. One potential confounding variable was the type of anesthesia used during surgery. The choice of anesthesia, such as general anesthesia or epidural anesthesia, can affect the perception of postoperative pain. General anesthesia may result in greater pain intensity compared to regional anesthesia because it affects the entire body and can lead to systemic inflammation and postoperative pain. Therefore, the type of anesthesia used in surgery should be considered as a potential confounding variable in this study. Another confounding variable was the surgical technique used during CABG surgery. The method of surgical incision, the use of minimally invasive techniques, or the complexity of the surgical procedure can all affect the severity of postoperative pain. For example, patients undergoing off-pump CABG surgery may experience less pain than patients undergoing traditional on-pump CABG surgery. Besides, the use of analgesics during and after surgery may have confounded the study results. The time, dose, and type of pain medication prescribed can affect the perception of pain in patients. The patients who receive adequate pain management during and after surgery may report less pain intensity compared to patients who do not receive adequate analgesia.

Research strengths

In this study, a gold standard randomized controlled trial was considered in the research, and this provided the possibility of random assignment of participants to different groups. This helped to minimize bias and ensured that any observed effect could be attributed to the intervention and no other factors. In addition, the focus on patients undergoing CABG surgery allowed for a targeted and homogeneous study population. This increased the internal validity of the results of the study. This study also focused on the effect of face-to-face training on pain severity. This intervention was both applicable and related to the pre-CABG surgery phase. Face-to-face education has the potential to provide important information and skills to patients for pain management. Collecting objective data on pain severity, such as using standard numerical rating scales, increased the reliability and validity of the study findings.

Research limitations

The patients studied in this research were only patients after CABG surgery and limited to one center, so the results are assigned to this group of patients. Moreover, some behaviors that were caused by anxiety or stress may have been considered in the assessment of pain severity. Considering that the pain tolerance threshold is different in different people, these factors affect the findings of the research. Another limitation of this study was that a number of patients in the sampling stage were asleep at the time determined to measure pain severity, so the researcher had to change the timing of recording information related to pain severity in these patients.

Conclusion

This study revealed that in-person preoperative pain education is effective in reducing the pain severity of patients undergoing CABG surgery. The results of this study indicated that two hours after removing the endotracheal tube, there was no statistically significant difference in pain severity between the intervention and control groups. However, at time points five and eight hours after endotracheal tube removal, the intervention group had significantly less pain severity than the control group. Moreover, the comparison of pain severity in patients who used analgesics (narcotic and non-narcotic) and those who used non-pharmaceutical methods demonstrated that the intervention group had significantly less pain severity in both cases. These findings suggest that while preoperative in-person exercise may not immediately reduce pain severity after the surgery, it may have a beneficial effect after several hours. In addition, the use of pain relievers in low doses as well as non-pharmacological methods by nurses can help in pain management in patients undergoing CABG surgery.

Acknowledgments

This study has been funded by the Iran University of Medical Sciences. Furthermore, we appreciate the collaboration of the Rajaie Cardiovascular, Medical and Research Center and the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery of the Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this article declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

2. Melly L, Torregrossa G, Lee T, Jansens JL, Puskas JD. Fifty years of coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Dis. 2018 Mar;10(3):1960-67.

3. Wang H, Sherwood GD, Liang S, Gong Z, Ren L, Liu H, et al. Comparison of Postoperative Pain Management Outcomes in the United States and China. Clin Nurs Res. 2021 Nov;30(8):1290-300.

4. Tüfekçi H, Akansel N, Sivrikaya SK. Pain Interference with Daily Living Activities and Dependency Level of Patients Undergoing CABG Surgery. Pain Manag Nurs. 2022 Apr;23(2):180-7.

5. Small C, Laycock H. Acute postoperative pain management. Br J Surg. 2020 Jan;107(2):e70-e80.

6. Alorfi NM. Pharmacological Methods of Pain Management: Narrative Review of Medication Used. Int J Gen Med. 2023 Jul 31;16:3247-56.

7. Huang C, Azizi P, Vazirzadeh M, Aghaei-Zarch SM, Aghaei-Zarch F, Ghanavi J, et al. Non-coding RNAs/DNMT3B axis in human cancers: from pathogenesis to clinical significance. J Transl Med. 2023 Sep 13;21(1):621.

8. Borujeni ET, Yaghmaian K, Naddafi K, Hassanvand MS, Naderi M. Identification and determination of the volatile organics of third-hand smoke from different cigarettes and clothing fabrics. J Environ Health Sci Eng. 2022 Feb 22;20(1):53-63.

9. Genova A, Dix O, Thakur M, Sangha PS. Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management and Addiction: A Review. Cureus. 2020 Feb 12;12(2):e6963.

10. Mahmoodi Chalbatani G, Gharagouzloo E, Malekraeisi MA, Azizi P, Ebrahimi A, Hamblin MR, et al. The integrative multi-omics approach identifies the novel competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) network in colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2023 Nov 9;13(1):19454.

11. Aroke EN, McMullan SP, Woodfin KO, Richey R, Doss J, Wilbanks BA. A Practical Approach to Acute Postoperative Pain Management in Chronic Pain Patients. J Perianesth Nurs. 2020 Dec;35(6):564-73.

12. Brescia AA, Piazza JR, Jenkins JN, Heering LK, Ivacko AJ, Piazza JC, et al. The Impact of Nonpharmacological Interventions on Patient Experience, Opioid Use, and Health Care Utilization in Adult Cardiac Surgery Patients: Protocol for a Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2021 Feb 16;10(2):e21350.

13. Ng SX, Wang W, Shen Q, Toh ZA, He HG. The effectiveness of preoperative education interventions on improving perioperative outcomes of adult patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2022 Aug 29;21(6):521-36.

14. Baxter SN, Johnson AH, Brennan JC, Dolle SS, Turcotte JJ, King PJ. The Efficacy of Telemedicine Versus In-Person Education for High-Risk Patients Undergoing Primary Total Joint Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2023 Jul;38(7):1230-7.e1.

15. Bjørnnes AK, Parry M, Lie I, Fagerland MW, Watt-Watson J, Rustøen T, et al. The impact of an educational pain management booklet intervention on postoperative pain control after cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2017 Jan;16(1):18-27.

16. Darville-Beneby R, Lomanowska AM, Yu HC, Jobin P, Rosenbloom BN, Gabriel G, et al. The Impact of Preoperative Patient Education on Postoperative Pain, Opioid Use, and Psychological Outcomes: A Narrative Review. Can J Pain. 2023 Nov 28;7(2):2266751.

17. Cravero JP, Agarwal R, Berde C, Birmingham P, Coté CJ, Galinkin J, et al. The Society for Pediatric Anesthesia recommendations for the use of opioids in children during the perioperative period. Paediatr Anaesth. 2019 Jun;29(6):547-71.

18. O'Brien T, Christrup LL, Drewes AM, Fallon MT, Kress HG, McQuay HJ, et al. European Pain Federation position paper on appropriate opioid use in chronic pain management. Eur J Pain. 2017 Jan;21(1):3-19.

19. Horn A, Kaneshiro K, Tsui BCH. Preemptive and Preventive Pain Psychoeducation and Its Potential Application as a Multimodal Perioperative Pain Control Option: A Systematic Review. Anesth Analg. 2020 Mar;130(3):559-73.

20. Ebrahimnejad M, Azizi P, Alipour V, Zarrindast MR, Vaseghi S. Complicated Role of Exercise in Modulating Memory: A Discussion of the Mechanisms Involved. Neurochem Res. 2022 Jun;47(6):1477-90.

21. Begum MR, Hossain MA. Validity and reliability of visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain measurement. Journal of Medical Case Reports and Reviews. 2019;2(11).

22. Karcioglu O, Topacoglu H, Dikme O, Dikme O. A systematic review of the pain scales in adults: Which to use? Am J Emerg Med. 2018 Apr;36(4):707-14.

23. Mohamed RM, Taha NM, Moghazy NA. Nursing practices regarding non-pharmacological pain management for patients with the cardiothoracic surgery at Zagazig University Hospitals. Zagazig Nursing Journal. 2022 Jan 1;18(1):16-28.

24. Sinderovsky A, Grosman-Rimon L, Atrash M, Nakhoul A, Saadi H, Rimon J, et al. The Effects of Preoperative Pain Education on Pain Severity in Cardiac Surgery Patients: A Pilot Randomized Control Trial. Pain Manag Nurs. 2023 Aug;24(4):e18-e25.

25. Tavakoli A, Norouzi M, Hajizadeh E. Patients' satisfaction from pain soothing after the surgery in Kerman Hospitals (2005). Journal of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. 2007 Sep 20;11(2).

26. Moradi M, Alimohammadi M, Naderi M. Measurement of total amount of volatile organic compounds in fresh and indoor air in four kindergartens in Ahvaz City. Iranian South Medical Journal. 2016 Nov 4;19(5):871-6.

27. Chiarotto A, Maxwell LJ, Ostelo RW, Boers M, Tugwell P, Terwee CB. Measurement properties of visual analogue scale, numeric rating scale, and pain severity subscale of the brief pain inventory in patients with low back pain: a systematic review. The Journal of Pain. 2019 Mar 1;20(3):245-63.

28. Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, Rosseland LA, Romundstad L, Hals EK, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008 Jul;101(1):17-24.

29. Gholami S, Naderi M, Moghaddam AM. Investigation of the survival of bacteria under the influence of supporting electrolytes KCl, CuI and NaBr in the electrochemical method. Mental Health. 2018 Jan 1;4(2):104-11.

30. Ertürk EB, Ünlü H. Effects of pre-operative individualized education on anxiety and pain severity in patients following open-heart surgery. Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2018 Jul-Aug;12(4):26-34.

31. Khalid A, Kausar S, Sadiqa A, Abid A, Jabeen S. Relevance of Preoperative Pain Education To The Cardiac Patients on Their Response To Postoperative Pain Therapy: Preoperative Pain Education to the Cardiac Patients. Pakistan BioMedical Journal. 2022 Feb 28:147-51.

32. Nargiz Koşucu S, Şelimen D. Effects of Music and Preoperative Education on Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery Patients' Anxiety. J Perianesth Nurs. 2022 Dec;37(6):807-14.

33. Blöndal K, Sveinsdóttir H, Ingadottir B. Patients' expectations and experiences of provided surgery-related patient education: A descriptive longitudinal study. Nurs Open. 2022 Sep;9(5):2495-505.

34. Kalogianni A, Almpani P, Vastardis L, Baltopoulos G, Charitos C, Brokalaki H. Can nurse-led preoperative education reduce anxiety and postoperative complications of patients undergoing cardiac surgery? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016 Oct;15(6):447-58.

35. Kol E, Alpar SE, Erdoğan A. Preoperative education and use of analgesic before onset of pain routinely for post-thoracotomy pain control can reduce pain effect and total amount of analgesics administered postoperatively. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014 Mar;15(1):331-9.

36. O'Donnell KF. Preoperative pain management education: a quality improvement project. J Perianesth Nurs. 2015 Jun;30(3):221-7.

37. Kim N, Yang J, Lee KS, Shin IS. The Effects of Preoperative Education for Patients With Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Cancer Nurs. 2021 Nov-Dec 01;44(6):E715-26.

38. Noor Hanita Z, Khatijah LA, Kamaruzzaman S, Karuthan C, Raja Mokhtar RA. A pilot study on development and feasibility of the 'MyEducation: CABG application' for patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. BMC Nurs. 2022 Feb 4;21(1):40.

39. Jarrah MI, Hweidi IM, Al-Dolat SA, Alhawatmeh HN, Al-Obeisat SM, Hweidi LI, et al. The effect of slow deep breathing relaxation exercise on pain levels during and post chest tube removal after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Int J Nurs Sci. 2022 Mar 15;9(2):155-61.

40. Bleicher J, Esplin J, Blumling AN, Cohan JN, Savarise Md M, Wetter DW, et al. Expectation-setting and patient education about pain control in the perioperative setting: A qualitative study. J Opioid Manag. 2021 Nov-Dec;17(6):455-64.

41. Giardina JL, Embrey K, Morris K, Taggart HM. The Impact of Preoperative Education on Patients Undergoing Elective Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: The Relationship Between Patient Education and Psychosocial Factors. Orthop Nurs. 2020 Jul/Aug;39(4):218-24.

42. Khoo ST, Lopez V, Ode W, Yu VSH, Lui JN. Psycho-social perspectives of nonsurgical versus surgical endodontic interventions in persistent endodontic disease. Int Endod J. 2022 May;55(5):467-79.

43. Nasir M, Ahmed A. Knowledge about postoperative pain and its management in surgical patients. Cureus. 2020 Jan 17;12(1).

44. Abimbola OE. A survey of nurses knowledge and utilization of non-pharmacological methods of pain control at two selected hospitals in Ibadan, OYO State. International Journal. 2021;2(3).

45. Lin I, Wiles L, Waller R, Caneiro JP, Nagree Y, Straker L, et al. Patient-centred care: the cornerstone for high-value musculoskeletal pain management. Br J Sports Med. 2020 Nov;54(21):1240-2.