Abstract

Introduction: Microsurgical training is an asset for deployed military orthopaedic surgeons who frequently treat hand or nerve injuries in the field. The objective of this study was to evaluate a microvascular surgery simulation model intended to prepare residents prior to their enrolment in conventional microsurgery degree training.

Methods: An experimental study was conducted to evaluate technical progress and satisfaction of military surgical residents using a model based on Japanese noodles with four tests of increasing difficulty. Objective endpoints included instruments handling, distribution, and quality of stitches, as well as anastomoses duration. Responses to the Structured Assessment of Microsurgery Skill self-assessment questionnaire were also analysed.

Results: Nine residents from different specialties participated in the study. Their anastomoses quality and average satisfaction significantly increased between the first and the last session (p<0.05). Conversely, the average operating time decreased significantly over the sessions (p<0.001).

Conclusion: This simulation model seems to constitute a satisfactory initiation to microsurgery and could limit the use of animal models. It could also be included in the continuing education of military surgeons who have an occasional microsurgical practice during deployments.

Keywords

Initiation, Microsurgery, Military, Simulation, Training

Introduction

The teaching of microsurgery is still based on animal models, which is the only way to faithfully replicate real operating conditions, in particular the difficulties of dissection and manipulation of the walls of micro-vessels [1]. On the other hand, initial training in the handling of instruments and anastomosis techniques can be carried out by means of simulation. Many nonbiological simulators have been developed and evaluated in recent years with the aim of limiting the use of animal models due to ethical and financial reasons [1-3].

Such simulation models could be useful for the initial and continuing education of military orthopaedic surgeons, who are occasionally called upon to repair vessels or nerves in the field [1,4,5]. In the French Army Health Service, the validation of a university degree in microsurgical techniques is thus part of the initial training of orthopaedic residents [5]. Prior initiation and regular training on a simulation model would allow them to better develop their technical capacities, dexterity, and self-control [6]. Such a model could also be used to maintain the skills of senior surgeons who do not have regular practice of microsurgery in their daily activity in their country.

We have therefore developed a microsurgical simulation model for military surgical residents that complies with the 3R principle: Reduce the number of animals in experiments, Refine the methodology used and Replace animal models [7]. The objective of this study was to evaluate the relevance of this model. Our hypothesis was that most participants would rapidly improve their performance without using the animal model.

Material and Methods

Study population

An experimental study was conducted among surgical residents assigned to the French Military Health Service Academy, Ecole du Val-de-Grâce, Paris. Included were residents from all specialties who had not yet training in microsurgery. Excluded were residents who had already been enrolled in a university degree in microsurgery.

Experimental protocol

The aim was to simulate the performance of various types of microvascular anastomoses over four training sessions. The simulation model was based on Japanese noodles of the konnyaku shirataki type as described by Prunières et al. [8]. Sutures were performed using standard microsurgical instruments (needle driver, dissecting forceps, double and single clamp), surgical magnifiers with 3.5x magnification (YEARSUN, China), and 10.0 nylon thread.

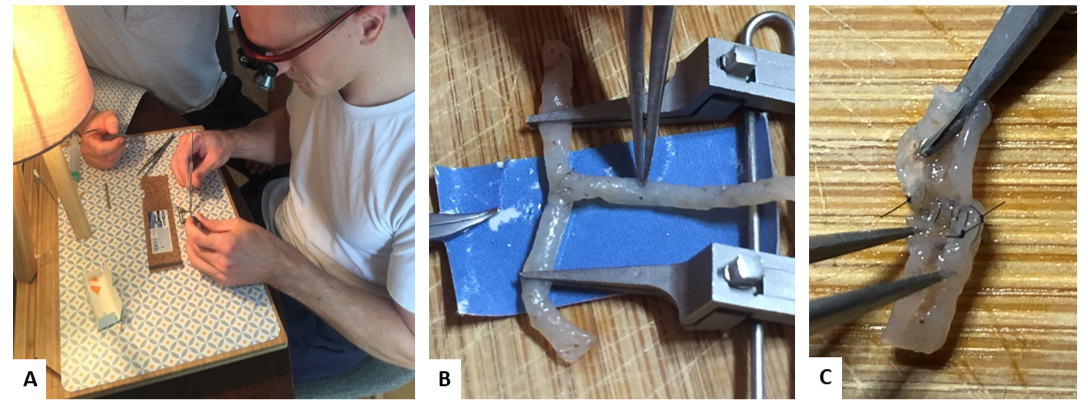

Each session followed the same protocol and was supervised by a qualified microsurgery instructor: 1) The participant adjusted his magnifiers after explanation and demonstration by the instructor (Figure 1A); 2) Each noodle was pierced with an intravenous catheter to provide visible and uniform light [8]; 3) The anastomosis was described by the instructor with the help of an explanatory diagram, then the suture was started after internal understanding of the objectives of the session; 4) The amount of time taken to perform the anastomosis was measured and the handling of the instruments evaluated by the monitor.

Figure 1: Photographs showing the working position of the participants (A), the performance of a lateral anastomosis (B) and the control of the anastomosis by the instructor at the end of the session (C).

At the end of each session, the instructor checked the permeability and quality of the anastomosis while the participant completed a self-assessment questionnaire. Each session consisted of different anastomoses of increasing difficulty: end-to-end anastomosis, end-to-side anastomoses (Figure 1B), and bypass with double end-to-end anastomosis (Table 1).

|

Session |

Anastomosis |

Technique |

Number of sutures |

|

1 |

End-to-end anastomosis |

Symmetrical Bi-angulation |

6 |

|

2 |

End-to-side anastomoses |

Symmetrical bi-angulation |

6 |

|

3 |

End-to-side anastomoses |

Nearby |

6 |

|

4 |

Bypass with double end-to-end anastomosis |

Symmetric bi-angulation |

12 |

Evaluation parameters

The anastomosis patency and the existence of leaks were assessed by injecting physiological saline through a catheter inserted proximally to the model [8]. The anastomosis quality was assessed from the inside after a longitudinal opening of the noodle (Figure 1C). Objective technical assessment was based on an adaptation of the rating scale described by Chan et al. [9] according to three criteria scored from 1 to 5: instrument handling, repair of stitches and quality of stitches (Table 2).

|

Score |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

Use of instruments |

Inadequate |

- |

Clumsy |

- |

Fluid |

|

Suture distribution |

Inadequate |

Poor |

Middle |

Good |

Excellent |

|

Suture performance |

At least one transfixing suture |

At least one wall rupture |

> 2 asymmetrical or undertight sutures |

≤ 2 asymmetrical or undertight sutures |

No or minimal errors |

The criteria for assessing the quality of the stitches were symmetry of the grip of the two edges, the tightness of the knots, the occurrence of a wall tear or a transfixing grip.

The anastomosis duration was also evaluated. It corresponded to the time elapsed between the positioning of the noodle on the double clamp and the section of thread during the last stitch. The amount of time was split in two during session 4 which included two anastomoses.

The subjective end-of-session self-assessment was performed using the Structured Assessment of Microsurgery Skill (SAMS) questionnaire, which has a high inter-rater reliability [9]. Fourteen criteria scored from 1 to 5 were assessed, with a maximum score of 70.

The primary endpoint was the comparison of scores obtained between the first and last session. The secondary endpoint included: 1) an independent assessment of each criterion in our rating scale; 2) a comparison of the participant’s self-assigned scores; 3) a comparison of the length of completion time between anastomoses during the resident’s advancement.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected using Excel software (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) to calculate means and standard deviations. Statistical analysis was performed using R software. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Nine residents with an average age of 28 (range: 24-35) completed all four sessions. There were six orthopaedic residents, two visceral surgery residents, and an ophthalmology resident. Their advancement within their six-year training course was uneven: two were in their first year, three in their second year, and three in their fourth year.

Anastomoses were permeable in all cases with constant leaks of various importance. Their quality significantly increased between the first and the last session for each of the three evaluated criteria (Table 3).

|

Session |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

P-value |

|

Use of instruments (max=5) |

2,222 |

2,556 |

3,111 |

3,444 |

2,869E-04 |

|

Suture distribution (max=5) |

2,667 |

2,778 |

3,111 |

3,556 |

1,087E-03 |

|

Suture performance (max=5) |

2,333 |

2,778 |

3,222 |

3,667 |

2.183E-05 |

|

Total, average (max=15) |

7,22 |

8,111 |

9,444 |

10,67 |

8.261E-06 |

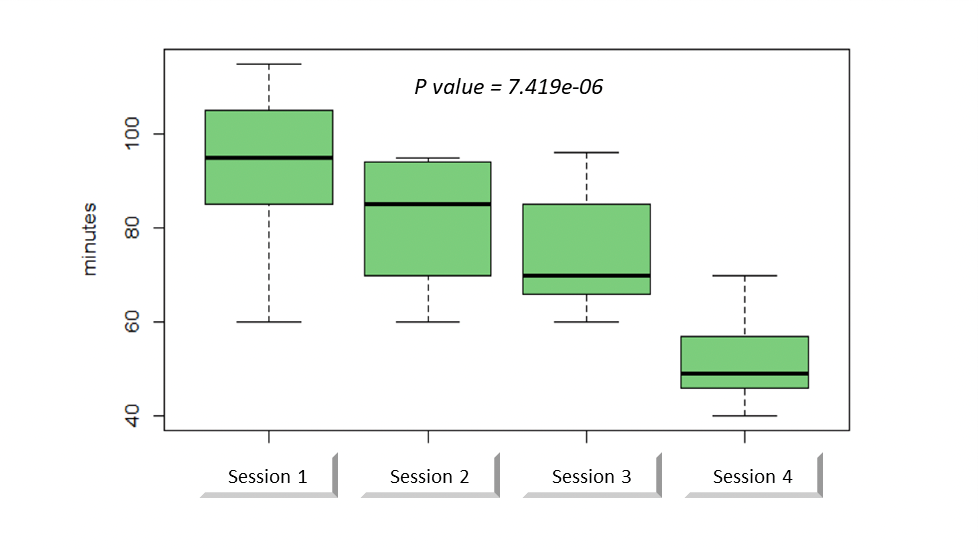

The average length of the procedure was 92 minutes (range: 60-115 minutes) during the first session versus 52 minutes (range: 40-70 minutes) during the last session. There was a significant decrease in anastomosis duration over the sessions (p <0.001, Figur. 2).

Figure 2: Anastomosis duration through sessions.

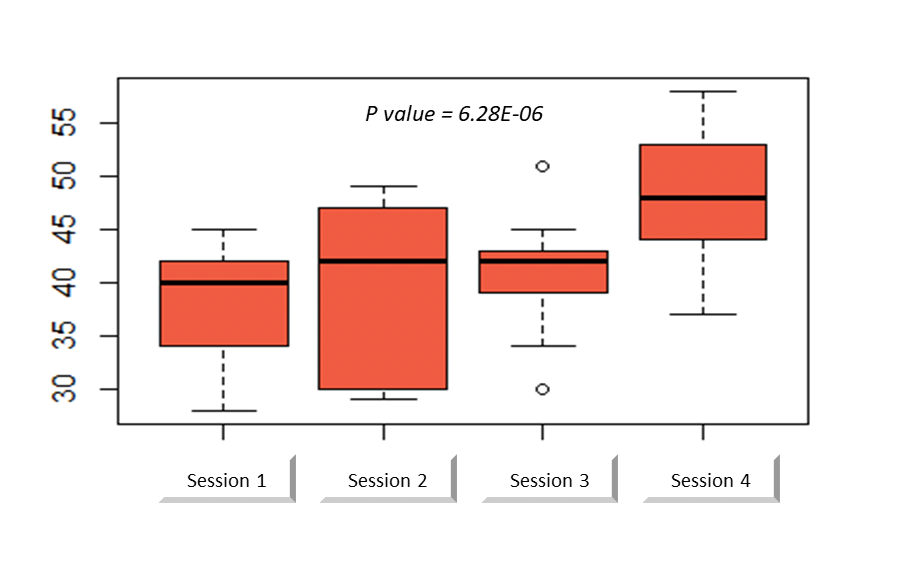

The average SAMS score was 37.5 (range: 28-45) during the first session compared to 47.5 (range: 37-58) during the last session. There was a significant increase in this score over the sessions (p <0.001, Figure. 3). Twelve out of 14 criteria were significantly increased, but two had only a statistical tendency to increase: "atraumatic use of the needle" (p = 0.07) and "section of the thread" (p = 0.052).

Figure 3: Structured Assessment of Microsurgery Skill score through sessions [9].

Discussion

Numerous studies have been published in recent years about experimental microsurgery with the objective to test various simulation models and alternative means of magnification under the microscope [1-3,8-10]. The goal is always the same: to facilitate the transmission of microsurgical techniques while limiting the cost and animals use. An ideal training model is a simple, reproducible, and easily accessible tool that also complies with regulations [7]. To our knowledge, this study is the first to report the use of a microsurgical simulation model for military surgeons in training. Although many of them will not have daily practice of microsurgery, they will have to use these skills occasionally within forward surgical units [5]. Thus, this work meets the need for training and regular practice of microsurgery for French military orthopaedic surgeons.

With the suggested model, there was a significant improvement in the technical performance of residents over the sessions, in both anastomosis quality and operating speed. These objective results, in association with a significant increase in the average SAMS score, provided reliable evidence of surgical skills improvement [9]. The presence of an instructor and the constant increase in technical difficulty probably explained this rapid progression from session to session. Such a companionship was similar to that of traditional university training which has proven its efficiency [11]. In fact, our method was based on previous studies and aimed to develop a model to meet the specific needs of military surgeons in terms of initial and continuing training [1,8,10].

The use of surgical magnifiers seemed obvious since they are often the only means of optical magnification available in the theatres of operations [5]. They have been used to perform digital revascularization and nerve repair in local patients managed by forward surgical teams [5]. Magnifiers are also used by experienced microsurgeons for microvascular anastomoses and nerve repairs in their daily practice [12]. They are an easily accessible tool, outside of any university or hospital structure, relatively inexpensive, and adapted to the Japanese noodle model with a diameter of about 1 mm. Ghabi et al. [1] previously demonstrated that they permit to reliably complete vascular anastomoses on the rat abdominal aorta which diameter (about 1 mm as well) is comparable to that of digital arteries.

The konnyaku shirataki noodle model was selected because of its availability, very low cost, and structure close to the animal model [8]. However, although this noodle is suitable for learning how to handle instruments, it does not take into account the difficulties of suturing on real vessels. Anastomosis patency and leakage could not be reliably assessed in this study. Pruniers et al. [8] pointed out that such a model does not reproduce the arterial spasm or thrombosis, nor the platelet deposit that seals the anastomosis in the first few minutes. Unlike them, we did not use a dye in the saline, which could have facilitated the detection of some leaks. The other drawbacks of this model lie in the noodle’s low resistance and high porosity. As Pruniers et al. [8], we observed many wall tears in the first sessions. However, parietal lesions became less frequent over the course of the sessions, indicating a progression of the criterion "atraumatic tissue manipulation". For all these reasons, we did not perform the Acland patency test, which we felt was hazardous and irrelevant [13]. We were therefore forced to limit our objective assessment to instrument handling and stitches quality. However, we found this model suitable for microsurgical initiation in alternative to more elaborate or expensive training simulators [14-16].

The other limitations of this study were related to the small sample size and its purely descriptive nature, without comparison to other simulation procedures, or to the reference training model in rat. Despite these limitations, our model allowed students to become familiar with the handling of microsurgical instruments and prepared them before transitioning on to the animal model. Its main advantage is easy access: any surgeon with magnifying glasses and a set of microsurgical instruments can use it to train alone in all circumstances, including during field deployments.

Conclusion

The proposed microsurgical simulation model appeared to be relevant for the initial training of military surgical residents. It allowed a fast technical advancement which is an excellent groundwork, and even a useful counterpart to classical training on animals. This simple and readily available tool could also be applied to the continuing education of military orthopaedic surgeons who have an occasional microsurgical practice in the field.

Key Messages

- Microsurgical practice in the combat theatre has been occasionally reported on in modern armed conflicts

- Field microsurgery is usually performed by trained orthopaedic surgeons with limited equipment

- We have developed and evaluated a microsurgical simulation model designed to meet the specific needs of military surgeons in terms of initial and continuing training

- This tool appeared to be an excellent groundwork for beginners and a useful counterpart to classical training on animals

Contributorship Statement

SABATE-FERRIS, Alexandre: Collected the data with me and contributed to their analysis.

CHAPON, Marie-Pauline: Contributed to the use of the analysis tools.

PFISTER, Georges: Wrote the abstract.

LEGAGNEUX, Josette: Provided us with the instruments and helped during the sessions.

DE GOEFFROY, Bernard: Reviewed the article and helped with the design of the analysis.

HARION, madeleine: did the translation.

MATHIEU, Laurent: Proofread the article, edited it and designed and produced the analysis.

GHABI Ammar: Did the manipulation with the residents and wrote the article.

Funding

No funding.

Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest for this study

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Nathalie de Garambé (Société EligiX - statistical reporting, Paris, France) for her assistance in the statistical analysis.

Availability of Data and Materials

Data are available and submitted only to this review.

References

2. Abi-Rafeh J, Zammit D, Mojtahed Jaberi M, Al-Halabi B, Thibaudeau S. Nonbiological microsurgery simulators in plastic surgery training: A systematic review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144:496–507.

3. Javid P, Aydın A, Mohanna PN, Dasgupta P, Ahmed K. Current status of simulation and training models in microsurgery: A systematic review. Microsurgery. 2019; 39:655–68

4. Mathieu L, Ghabi A, Amar S, Murison JC, Boddaert G, Levadoux M. Digital replantation in forward surgical units: Cases report. SICOT-J. 2018;4:9.

5. Mathieu L, Ghabi A, Amar S, Murison JC, Boddaert G, Levadoux M. The state of microsurgical practice in French forward surgical facilities from 2003 to 2015. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2019;38:358–63.

6. Vinagre G, Villa J, Amillo S. Microsurgery training: Does it improve surgical skills? J Hand Microsurg. 2017; 9:47–8.

7. Bulger RE. Use of animals in experimental research: A scientist’s perspective. Anat Rec. 1987;219: p. 215–20.

8. Prunières GJ, Taleb C, Hendriks S, Miyamoto H, Kuroshima N, Liverneaux PA, et al. Use of the Konnyaku Shirataki noodle as a low fidelity simulation training model for microvascular surgery in the operating theatre. Chir Main. 2014;33:106–11.

9. Chan W-Y, Matteucci P, Southern SJ. Validation of microsurgical models in microsurgery training and competence: A review. Microsurgery. 2007;27:494–9.

10. Malik MM, Hachach-Haram N, Tahir M, Al-Musabi M, Masud D, Mohanna PN. Acquisition of basic microsurgery skills using home-based simulation training: A randomised control study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:478–86.

11. Bergmeister KD, Kneser U, Kremer T, Harhaus L, Daeschler SC, Pierer G, et al. New concept for microsurgical education: The training academy of the German Working Group for Microsurgery of Peripheral Nerves and Vessels: Results of a 4-year evaluation. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2019;51:327–33

12. Stanbury SJ, Elfar J. The use of surgical loupes in microsurgery. J Hand Surg. 2011;36:154–6.

13. Acland RD. Signs of patency in small-vessel anastomosis. Surgery. 1972;72:744–8.

14. Hüsken N, Schuppe O, Sismanidis E, Beier F. MicroSim - a microsurgical training simulator. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;84:205–9.

15. Hayashi K, Hattori Y, Yii Chia DS, Sakamoto S, Marei A, Doi K. A supermicrosurgery training model using the chicken mid and lower wing. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2018;71:943–5.

16. Lovato RM, Campos Paiva AL, Pesente FS, de Oliveira JG, Ferrarez CE, Vitorino Araújo JL, et al. An Affordable stereomicroscope for microsurgery training with fluorescence Mode. World Neurosurg. 2019;130:142–5.