Abstract

Introduction: Fascioliasis is an infectious disease caused by Fasciola hepatica or Fasciola gigantica. Fasciola hepatica mainly infects livestock, causing fascioliosis by settling in the biliary tract. Humans get infected through contaminated water or by consuming uncooked aquatic plants. While rare, fascioliasis remains a concern, even in developed countries. Turkey, particularly the Van region, is endemic for Fasciolasis, providing a suitable environment for the parasite. In this study, the clinical and laboratory findings of 37 patients diagnosed with fascioliasis categorized according to eosinophil count in Van city of Turkey are summarized.

Method: This retrospective cross-sectional study included 37 patients diagnosed with Fasciola hepatica infection. Patients were categorized based on their eosinophil count: normal (<500/mm3) and eosinophilia (≥500/mm3). Their laboratory data were analyzed separately.

Results: Between January 2017–February 2024, 37 patients (28 females, mean age 44±17 years) were diagnosed with Fasciolasis. The most common symptoms were abdominal pain, fever, and right upper abdominal tenderness. Abnormal liver function tests were frequently observed in laboratory tests. Of the 37 patients, 20 had normal eosinophil counts, while 17 had eosinophilia. The diagnosis was confirmed via Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), live Fasciola hepatica parasites were found in the common bile duct. All patients were treated with triclabendazole, and live parasites were extracted during ERCP.

Conclusion: Peripheral eosinophilia is commonly observed alongside abdominal pain, fever, and liver enzyme elevation in fascioliasis. While eosinophil counts are usually <500/mm3, they can rise significantly. Parasitic infections, especially fascioliasis, should be considered a key cause of eosinophilia, especially in developing countries.

Keywords

Fasciola hepatica, Fasciolasis, Eosinophil, Parasites, Liver trematode, Parasitic infections

Abbreviations

ALP: Alkaline Phosphatase; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; CRP: C-Reactive Protein; ERCP: Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography; GGT: γ-glutamyl Transferase; IHA: Indirect Haemagglutination Test; IQR: Interquartile Range; SD: Standard Deviation

Introduction

Fasciola hepatica is a liver trematode with worldwide animal distribution, most commonly seen in sheep- and cattle-raising areas [1,2]. The flukes are leak-like, flat worms, measuring 2–4 cm [3]. The number of reports of Fasciola hepatica has increased significantly recently, and several geographical areas have been described as endemic for the disease in humans, with prevalence and incidence ranging from low to very high [4,5]. They are widely distributed and infect a wide range of definitive hosts, causing enormous economic loss due to reduced productivity in domestic ruminants [6]. Globally, it is estimated that about 17 million people are infected [7] with severe health consequences [8]. Fasciola hepatica is widely distributed in Europe [9], temperate regions of Asia, Africa, Oceania and America whilst Fasciola gigantica is mainly restricted to Africa and Asia [7].

In humans, the infection begins with the ingestion of watercress or contaminated water containing encysted larva. The larva excyst in the stomach, penetrate the duodenal wall, escape into the peritoneal cavity, and then pass through the liver capsule to enter the biliary tree [3]. Human fascioliasis has two phases. The hepatic phase (other name is acute phase) of the disease begins one to three months after ingestion of metacercariae, with penetration and migration through the liver parenchyma toward the biliary ducts [3,10,11]. Common signs and symptoms of the hepatic phase are abdominal pain, fever, eosinophilia, and abnormal liver function tests [3,10,12,13]. The biliary phase (other name is chronic phase) of the disease usually presents with intermittent right upper quadrant pain with or without cholangitis or cholestasis [14].

The immature larvae crawl through the intestinal wall, peritoneal cavity, liver capsule and liver tissue, eventually reaching the bile ducts. The hepatic phase lasts for about 3 to 4 months, concluding when the larvae reach the bile ducts and mature there. The chronic phase is initiated when the immature larvae reach the bile ducts, develop into adult flukes and begin to produce eggs. The eggs move from the bile ducts to the intestines and are eventually excreted in the feces. During this period, the patient may remain asymptomatic for months, years, or even indefinitely. Routine blood tests may show only peripheral eosinophilia, which is usually less noticeable than during the acute phase [15].

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT), and bilirubin concentration in the blood of patients are often increased during larval migration [16] and during the chronic phase [15].

Eosinophils are very important cells in the response to helminth infections, as they have been shown to cause the death of parasites in vitro [17]. Eosinophilia is defined as a peripheral blood eosinophil count 500/mm3. Causes and associated disorders are myriad but often represent an allergic reaction or a parasitic infection [18]. The degree of eosinophilia can be categorized as mild (500–1,500 cells/mm3), moderate (1,500-5,000 cells/mm3), or severe (>5,000 cells/mm3) [19]. Eosinophilia is often the most apparent hematological abnormality in Fasciola infections [20–21]. Eosinophilia is more prominent and less variable during the acute phase than during the chronic phase [15].

When the literature was analyzed, no study investigating the relationship between the degree of eosinophil count and Fasciola hepatica infection in any country was found before. Eastern Anatolia region of our country is a region where animal husbandry is developed and parasite infections are common. Fasciola hepatica cases are encountered more frequently during ERCP in Gastroenterology Clinic compared to other regions. In our study, which included the highest number of patients in the literature, we aimed to see the relationship between the degree of eosinophil count in Fasciola hepatica cases.

Materials and Methods

In our retrospective cross-sectional study, we analyzed electronic or record-based medical data of 37 patients who were diagnosed with Fasciola hepatica infection were included in this retrospective cross-sectional study. They were referred to our hospital with suspicion of choledocolithiasis between January 2017 and February 2024. In all patients, Fasciola hepatica parasite was detected on ERCP, and the diagnosis was made. No Fasciola eggs or larvae were found in the stool examination of any patient. The demographic characteristics such as age, gender, clinical symptoms and diagnosis were recorded. In the patients with eosinophilia, routine blood tests such as complete blood cell counts, acute phase reactants [C-reactive protein (CRP)], liver and kidney function tests were measured. According to the count of eosinophils in peripheral blood, patients divided into 2 categories—normal eosinophil count <500/mm3 and eosinophilia (≥500). Demographic and laboratory data of the groups were analyzed separately.

This work has been carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) of the World Medical Association. This retrospective study was approved by local ethics committee (decision number: GOKAEK-2024-01-12), and all patients provided informed written consent for participation.

Statistical analysis

It was done using SPSS software (version 21.0 for Windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Parametric variables were expressed as means with standard deviations, while non-parametric variables were reported as medians along with interquartile ranges (IQR). For categorical variables, the number of cases and percentages were reported. When comparing numerical variables, the Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test was applied, depending on the distribution of the variables. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 37 patients, 73.7% (n=28) of patients were female and a median age (interquartile range) was 44±17 years. Baseline demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics of the patients are given in Table 1. All patients had chronic phase. The clinical presentations and general conditions of the cases were fairly similar. The patients main complaints were severe jaundice and pain in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Abdominal ultrasound revealed minimal intrahepatic and mild extrahepatic biliary dilatation while other organs were normal, and no stones were observed. Twelve patients were found to have leukocytosis at the beginning of disease.

|

|

n:37 |

|

Age, years mean ± SD

|

44±17 |

|

Gender, female/male n (%)

|

28/9 (73.7/26.3) |

|

CRP, mg/dL median (IQR)

|

8.4 (16.31) |

|

Leukocyte /mm³ mean±SD

|

13.94±1.47 |

|

Neutrophil mcL mean±SD

|

5070±3053 |

|

Lymphocyte mcL mean±SD

|

2176±1049 |

|

Hemoglobin g/dL mean±SD

|

13.94±1.47 |

|

Eosinophil /mm3 median (IQR)

|

390 (1,195) |

|

AST, U/ L median (IQR)

|

47 (84) |

|

ALT, U/L mean±SD

|

120±91 |

|

GGT, U/L mean±SD

|

272±237 |

|

ALP, IU/L median (IQR)

|

222 (188) |

|

Total bilurubin, mg/dL median (IQR)

|

0.70 (1.38) |

|

Direct bilurubin, mg/dL median (IQR)

|

0.23 (1) |

|

Abbreviations: ALP: Alkaline Phosphatase; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; CRP: C-Reactive Protein; ERCP: Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography; GGT: γ-glutamyl Transferase; IQR: Interquartile Range; SD: Standard Deviation |

|

Blood tests revealed normal eosinophil count in 20 cases, mild eosinophilia in 9 cases, moderate eosinophilia in 6 cases, severe eosinophilia in only 2 cases. The laboratory findings before treatment elevations in the CRP in 25 (68%), ALT in 21 (57%), AST in 19 (51%), ALP in 14 (38%), GGT in 30 (81%), and serum total bilirubin in 12 (32%) serum direct bilurubin in 14 (38%) patients. In 19 patients ALT was higher than AST. In 3 patients AST was higher than ALT. Nine patients had cholestasis enzyme (GGT, ALP) dominance compared to AST and ALT. Eosinophilia was present in 17 (46%), leukocytosis was present in 12 (32%), anemia was in 2 (5%) patients. Platelet counts were normal in all patients.

ERCP was performed in all patients because there were clinical and laboratory findings of extrahepatic biliary obstruction. Before ERCP, we considered the diagnosis of Fascioliasis in 17 (46%) patients with eosinophilia. Cholangiography showed slight extrahepatic and intrahepatic biliary dilatation in 2 (5%) patients. In the remaining 35 (95%) patients, the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary systems were within normal diameter. ERCP demonstrated a radiolucent, roughly crescent-shaped shadow in the common bile duct in all patients. After standard sphincterotomy, live Fasciola hepatica was removed using a balloon catheter from the extrahepatic bile ducts. We routinely administered 1 gram ceftriaxone at least one hour before ERCP to prevent post-ERCP cholangitis. We did not administer antibiotics to any patient after ERCP. After diagnosis of fascioliasis, triclabendazole was administered at a dose of 10-12 mg/kg for 1 day to all patients. We did not observe any side-effects related to triclabendazole administration.

Discussion

Fasciolasis is an emergeing disease and becoming a public health problem in many developing countries [19]. While Fasciola hepatica is widespread in the world, Fasciola gigantica is more common in tropical regions. Fasciola hepatica is endemic to Europe and Asia [22]. In studies reported from different regions of Turkey, the prevalence of Fasciola hepatica varies between 0.79–10.3%, which proves that Fasciola hepatica infection is not rare in Turkey [23–28]. Our hospital is a tertiary care center in the east of Turkey that serves approximately 2 million people. Most of the patients in this study resided in rural areas and had a history of consuming watercress grown in areas where sheep were raised.

Patients with fascioliasis were referred our hospital for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. In our study, we analyzed the eosinophil count, which should be considered in the diagnostic criteria in patients with fasciolasis. There is no previous study in the literature including such a large number of fascioliasis patients. Our country can be considered as one of the endemic regions due to parasitic diseases, socioeconomic conditions and hygiene problems.

The distribution of fascioliasis by sex presents inconsistent results. A large study by Parkinson et al. in the Bolivian Altiplano, involving approximately 8,000 people of all ages, found no significant association with sex [4]. However, studies in other regions have shown a higher prevalence in females, especially among children [29]. In a study of more than 21,000 cases in Egypt, Curtale et al. reported that females had a significantly higher prevalence of fascioliasis and passed more eggs in faeces than males [30]. In our study, we observed that the majority of cases were female (73.7% n:28).

In our study, 20 patients had chronic phase. In this phase; the main laboratory findings are cholestasis including predominantly elevated serum ALP, GGT and total bilirubin [14,21,29]. The patients’ main complaints were severe jaundice, pain in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Parasitic infections can cause secondary eosinophilia that can be of the moderate to severe level [31]. There is marked eosinophilia in the acute period, while the number of eosinophils decreases in the chronic period [32]. Demirci et al. found 46 seropositive fasciolasis patients 756 eosinophilic patients and 320 non-eosinophilic patients and when they looked at the eosinophil counts, they reported that the most common eosinophilia was mild (350-1,500/mm3) (n:38 %83), then moderate (1,500-5,000/mm3) (n:7, 15%) and the least severe eosinophilia (>5000/mm3) (n:1, 2%) [27]. Similarly to the literature, we reported in patients with fasciolasis, the eosinophil count can increase up to severe eosinophilia. In this study, there were seen normal eosinophil count in 20 cases (54%), mild eosinophilia in 9 cases (24.3%), moderate eosinophilia in 6 cases (16.2%), severe eosinophilia in only 2 cases (5.5%).

Fascioliasis is contracted through the consumption of contaminated freshwater vegetables or water. Patients typically present with fever, leukocytosis, high-grade eosinophilia, and right upper quadrant pain [33–35]. Our clinical and laboratory examination data are in accordance with the literature. In countries like Turkey where serologic tests were not routinely used, Fasciola hepatica infection was diagnosed with obstruction of the extrahepatic bile ducts, biliary colic, jaundice and cholangitis [3,5].

The diagnosis of fascioliasis may be delayed due to the broad spectrum of differential diagnosis and the rarity of Fasciola hepatica infection [36]. Abnormal laboratory and radiological findings in Fasciola hepatica infection may represent infection with parasites such as liver abscess, malignancy, cholecystitis, sclerosing cholangitis, ruptured hydatid cyst, and ascariasis [37,38]. There is no definitive test for the diagnosis of fascioliasis. In the serological diagnosis of Fasciola hepatica infection, the specificity of the indirect hemagglutination test (IHA) using purified adult Fasciola hepatica antigen F1 is 96.9% [39]. Sometimes the diagnosis can be made during unnecessary surgery, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and ERCP [40]. In our study, adult Fasciola hepatica parasites were detected in the biliary tract by ERCP without serological diagnosis.

The intricate pathophysiology of fascioliasis can pose diagnostic challenges for clinicians. The presence of risk factors such as exposure to endemic areas, raw water plants, or untreated water may raise the clinical suspicion [41].

Anamnesis, laboratory and imaging methods have important clues for the diagnosis of Fasciola hepatica. Fasciola hepatica should be suspected if patients have a history of eating watercress in their anamnesis [42]. In our cases, all patients reported eating watercress or other grass-like cresses. The presence of eosinophilia is an important finding for fasciolasis. In the study by Ülger et al. the frequency of eosinophilia was found to be 79% [41]. In the study by Akpinar et al. the frequency of eosinophilia was found to be 82% [42]. In our study, the frequency of eosinophilia was 46%. Imaging methods are also very important for the diagnosis of fascioliasis. ERCP is the preferred method for patients in the chronic phase. ERCP enables both definitive diagnosis and treatment of the parasite [43,44]. In our study, all patients were diagnosed and treated with ERCP.

When the fasciolasis patient groups were analyzed, we found that the mean age and male/female ratio of the group with eosinophilia were higher than the group with normal eosinophil count [51±17 vs 38±15 p=0.039, 18/2 (90/10 %) vs 10/7 (59/41 %) p=0.028] (Table 2).

|

|

Normal eosinophil (<500/mm3) n:20 |

Eosinophilia (≥500/mm3) n:17 |

p value |

|

Age years mean±SD

|

51±17 |

38±15 |

0.039 |

|

Gender female/male n (%)

|

18/2 (90/10) |

10/7 (59/41) |

0.028 |

|

CRP mg/dL median (IQR)

|

10 (40) |

20 (28) |

0.293 |

|

Hemoglobin g/dL mean±SD

|

13.4±1.7 |

14.3±1.0 |

0.088 |

|

Leukocyte/mm³ mean±SD |

7,250±1615 |

9,540±664 |

0.325

|

|

Neutrophil mcL mean±SD

|

4,384±1,538 |

4,864±1,658 |

0.318 |

|

Lymphocyte mcL mean±SD

|

2,022±619 |

2,228±732 |

0.110 |

|

Eosinophil/mm3 median (IQR)

|

245 (212) |

1,470 (2,610) |

<0.001 |

|

AST U/L median (IQR)

|

22 (104) |

55 (74) |

0.046 |

|

ALT U/L mean±SD

|

79 ±102 |

133±84 |

0.543 |

|

GGT U/L mean±SD

|

162±201 |

307±249 |

0.046 |

|

ALP IU/L median (IQR)

|

95 (445) |

224 (294) |

0.247 |

|

Total bilurubin mg/dL median (IQR)

|

0.4 (0.7) |

1.3 (2.2) |

0.033 |

|

Direct bilurubin mg/dL median (IQR)

|

0.2 (0.3) |

0.8 (2.2) |

0.192 |

|

Abbreviations: ALP: Alkaline Phosphatase; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; CRP: C-Reactive Protein; ERCP: Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography; GGT: γ-glutamyl Transferase; IQR: Interquartile Range; SD: Standard Deviation |

|||

A recent analysis from the Austria population cohort [45] showed that younger individuals have much higher blood eosinophil counts, which is similar to our findings. In addition, in a cohort study conducted in Austria [45], eosinophil counts were higher in male gender than in female gender, which supports our study.

There are few studies showing the relationship between fasciolasis and eosinophil count in our country. Demirci and colleagues investigated fascioliasis in a group of eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic patients in the Isparta region of Turkey. According to the results of their study, the prevalence of fascioliasis was higher among patients with eosinophilia [27].

Tissue damage in fascioliasis may result from the proteolytic enzymes secreted by the parasites, immune responses to the parasites' excretory/secretory products and tegument, as well as the mechanical effect of the parasites on the tissue [46].

Frigerio and colleagues showed the beneficial immunomodulatory roles of eosinophils during Fasciola hepatica infection by limiting IL-10 production and enhancing the capacity of specific antibodies to induce eosinophil degranulation, thus contributing to the understanding of eosinophil function during helminth infections [47].

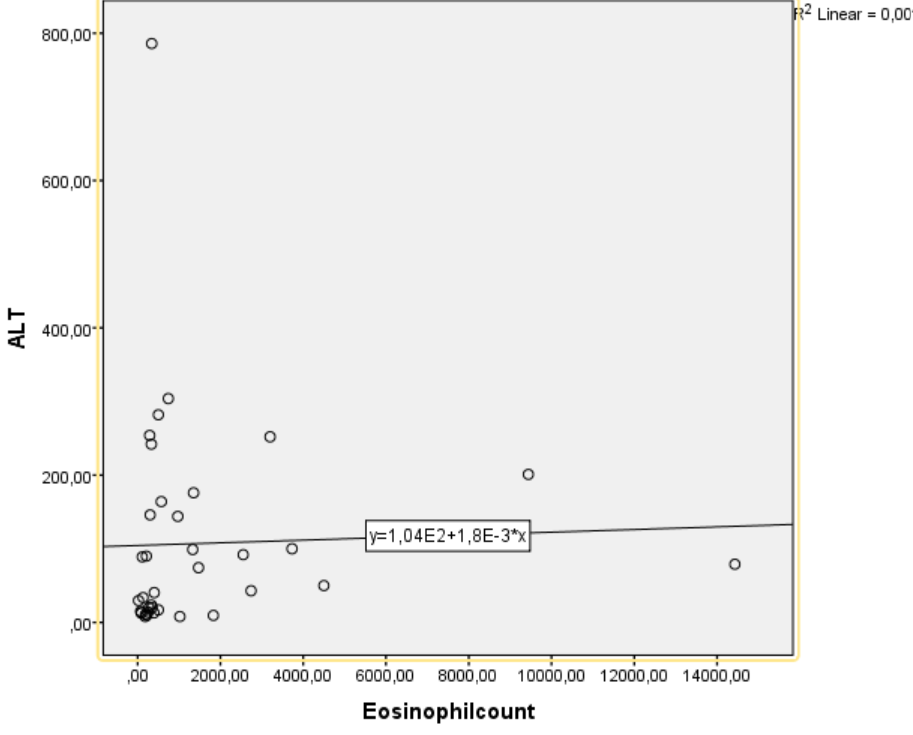

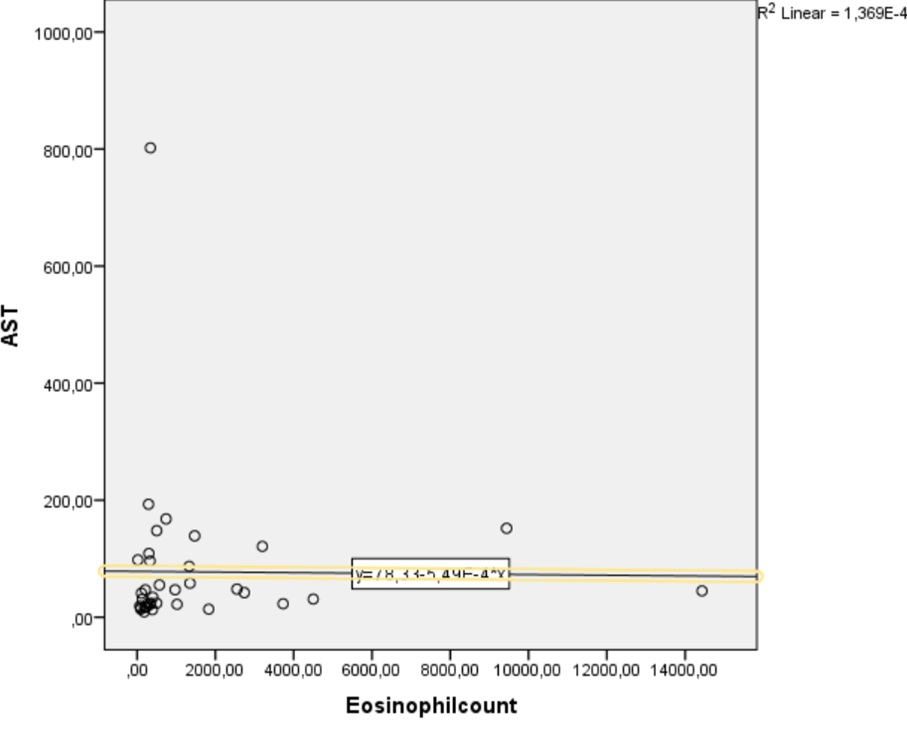

Eosinophils could also derive from the blood due to portal hypertension produced by fibrosis in livers [48]. When compared of characteristics of fascioliasis in eosinophil groups; AST, GGT, total bilurubin levels were higher in the eosinophilia group compared to the group with normal eosinophil count (p=0.046 vs. p= 0.046 vs. p=0.033 respectively). In addition, we have shown that eosinophil count is weakly but significantly correlated with ALT and AST (r=0.335, p=0.043 vs. r=0.387, p=0.018 respectively) (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. The relationship between eosinophil count and ALT was measured by Spearman correlation. A weak but significant positive correlation was found between these parameters [r=0.387, p=0.018].

Figure 2. The relationship between eosinophil count and AST was measured by Spearman correlation. A weak but significant positive correlation was found between these parameters [r=0.335, p=0.043].

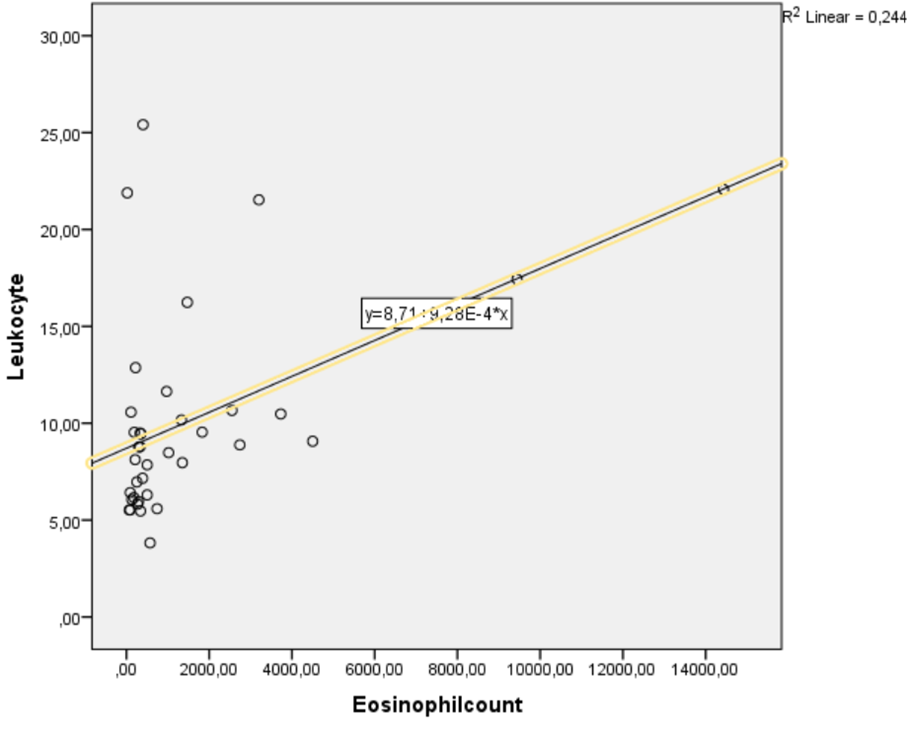

In the acute phase of fasciolasis, elevated eosinophils are observed [49]. In Demirci et al. study; retrospective evaluation of 14 patients found to have leukocytosis at the beginning of fasciolasis [27]. In our study, eosinophil count was found to be weakly but positively correlated with leucocytes (r=0.494, p=0.002) (Figure 3). This suggests that the patients were in the acute period of fasciolasis.

Figure 3. The relationship between eosinophil count and leukocyte was measured by Spearman correlation. A weak but significant positive correlation was found between these parameters [r=0.494, p=0.002].

In our study, we demonstrated a significant association between Fasciola hepatica infection and eosinophilia. Our study has certain limitations; due to operational constraints, serological tests could not be performed for all patients. Existing literature includes various biomarker studies focusing on the relationship between eosinophilia and tissue or cellular injury. In mouse models, SIRT1 inhibition reduced asthma-like inflammation (airway inflammation) and decreased the number of eosinophils in bronchoalveolar lavage [50]. This suggests that SIRT1 has a functional role in eosinophil migration and the inflammatory process. Given the role of eosinophils in helminth-related immune responses, recent evidence suggesting that the anti-aging gene Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) plays a critical role in immune regulation and eosinophil control is noteworthy [51]. Inactivation of SIRT1 has been linked to autoimmune conditions and multi-organ disease syndromes [52–54]. Therefore, assessing plasma SIRT1 levels in patients with fascioliasis may help clarify the underlying immune mechanisms and offer insight into the prevention of programmed cell death and immune dysregulation in these cases.

Conclusion

As seen from these results, although the eosinophil count is usually <1500/mm3 in patients with fasciolasis, the eosinophil count can increase up to severe eosinophilia. Parasitic infections especially fasciola should be considered as an important cause of eosinophilia, particularly in developing countries.

References

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fascioliasis—DPDx: laboratory identification of parasites of public health concern. 2 May 2019. Accessed 1 April 2023.

3. Lim JH, Mairiang E, Ahn GH. Biliary parasitic diseases including clonorchiasis, opisthorchiasis and fascioliasis. Abdom Imaging. 2008 Mar-Apr;33(2):157–65.

4. Parkinson M, O'Neill SM, Dalton JP. Endemic human fasciolosis in the Bolivian Altiplano. Epidemiol Infect. 2007 May;135(4):669–74.

5. Mas-Coma MS, Esteban JG, Bargues MD. Epidemiology of human fascioliasis: a review and proposed new classification. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77(4):340–6.

6. Haridwal S, Malatji MP, Mukaratirwa S. Morphological and molecular characterization of Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica phenotypes from co-endemic localities in Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal provinces of South Africa. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2021 Feb 3;22:e00114.

7. Mas-Coma S, Valero MA, Bargues MD. Chapter 2. Fasciola, lymnaeids and human fascioliasis, with a global overview on disease transmission, epidemiology, evolutionary genetics, molecular epidemiology and control. Adv Parasitol. 2009;69:41–146.

8. Mas-Coma S, Bargues MD, Valero MA. Diagnosis of human fascioliasis by stool and blood techniques: update for the present global scenario. Parasitology. 2014 Dec;141(14):1918–46.

9. Robinson MW, Dalton JP. Zoonotic helminth infections with particular emphasis on fasciolosis and other trematodiases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009 Sep 27;364(1530):2763–76.

10. Koç Z, Ulusan S, Tokmak N. Hepatobiliary fascioliasis: imaging characteristics with a new finding. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2009 Dec;15(4):247–51.

11. Kabaalioğlu A, Cubuk M, Senol U, Cevikol C, Karaali K, Apaydin A, et al. Fascioliasis: US, CT, and MRI findings with new observations. Abdom Imaging. 2000 Jul-Aug;25(4):400–4.

12. Teichmann D, Grobusch MP, Göbels K, Müller HP, Koehler W, Suttorp N. Acute fascioliasis with multiple liver abscesses. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000;32(5):558–60.

13. Aksoy DY, Kerimoğlu U, Oto A, Ergüven S, Arslan S, Unal S, et al. Fasciola hepatica infection: clinical and computerized tomographic findings of ten patients. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2006 Mar;17(1):40–5.

14. Ozer B, Serin E, Gümürdülü Y, Gür G, Yilmaz U, Boyacioğlu S. Endoscopic extraction of living fasciola hepatica: case report and literature review. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2003 Mar;14(1):74–7.

15. Harrington D, Lamberton PHL, McGregor A. Human liver flukes. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Sep;2(9):680–689.

16. Espino AM, Duménigo BE, Fernández R, Finlay CM. Immunodiagnosis of human fascioliasis by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using excretory-secretory products. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1987 Nov;37(3):605–8.

17. Klion AD, Nutman TB. The role of eosinophils in host defense against helminth parasites. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004 Jan;113(1):30–7.

18. Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilia. N Engl J Med. 1998 May 28;338(22):1592–600.

19. Falchi L, Verstovsek S. Eosinophilia in Hematologic Disorders. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2015 Aug;35(3):439–52.

20. Mas CS, Bargues M. Human liver flukes: a review. Res. Rev. Parasitol. 1997 Jan 1;57:145–218.

21. Gulsen MT, Savas MC, Koruk M, Kadayifci A, Demirci F. Fascioliasis: a report of five cases presenting with common bile duct obstruction. Neth J Med. 2006 Jan;64(1):17–9.

22. Good R, Scherbak D. Fascioliasis. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537032/

23. Ozturhan H, Emekdaş G, Sezgin O, Korkmaz M, Altintaş E. Seroepidemiology of Fasciola Hepatica in Mersin province and surrounding towns and the role of family history of the Fascioliasis in the transmission of the parasite. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2009 Sep;20(3):198–203.

24. Şahin İ, Yazar S, Yaman O. KAYSERİ-KARPUZSEKİSİ HAVZASINDA YAŞAYAN İNSANLARDA FASCİOLA HEPATİCA PREVALANSI. Sağlık Bilimleri Dergisi. 2008;17(2):97–103.

25. Yilmaz H, Gödekmerdan A. Human fasciolosis in Van province, Turkey. Acta Trop. 2004 Oct;92(2):161–2.

26. Şeker Y. Çukurova Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilimleri Enstitüsü; 2005. [The investigation of Fasciola hepatica antibodies with serological method on human who live in Residental Area of Adana] Turkish.

27. Demirci M, Korkmaz M, Kaya S, Kuman A. Fascioliasis in eosinophilic patients in the Isparta region of Turkey. Infection. 2003 Jan;31(1):15–8.

28. Kaplan M, Kuk S, Kalkan A, Demirdağ K, Ozdarendeli A. Fasciola hepatica seroprevalence in the Elaziğ region. Mikrobiyoloji Bulteni. 2002 Jul 1;36(3-4):337–42.

29. El-Sahn F, Farghaly A, El-Masry A, Mandil A, Gad A, El-Morshedy H. Human fascioliasis in an Egyptian village: prevalence and some epidemiological determinants. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 1995;70(5-6):541–57.

30. Curtale F, Hassanein YA, Barduagni P, Yousef MM, Wakeel AE, Hallaj Z, et al. Human fascioliasis infection: gender differences within school-age children from endemic areas of the Nile Delta, Egypt. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007 Feb;101(2):155–60.

31. Kuang FL. Approach to Patients with Eosinophilia. Med Clin North Am. 2020 Jan;104(1):1–14.

32. Bogoch ıı (author), Ryan ET (section editor), Baron EL (deputy editor). ınfectious causes of peripheral eosinophilia. upToDate. 2023.

33. Fica A, Dabanch J, Farias C, Castro M, Jercic MI, Weitzel T. Acute fascioliasis--clinical and epidemiological features of four patients in Chile. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012 Jan;18(1):91–6.

34. Kayabali I, Gokcora IH, Yerdel MA, Ormeci N. Hepatic fascioliasis and biliary surgery. Int Surg. 1992 Jul-Sep;77(3):154–7.

35. Bengisun U, Ozbas S, Sarioglu U. Fascioliasis observed during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 1999 Feb;384(1):84–7.

36. Kabaalioğlu A, Cubuk M, Senol U, Cevikol C, Karaali K, Apaydin A, et al. Fascioliasis: US, CT, and MRI findings with new observations. Abdom Imaging. 2000 Jul-Aug;25(4):400–4.

37. Azab M el-S, el Zayat EA. Evaluation of purified antigens in haemagglutination test (IHA) for determination of cross reactivities in diagnosis of fascioliasis and schistosomiasis. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1996 Dec;26(3):677–85.

38. Mas-Coma S, Bargues MD, Valero MA. Human fascioliasis infection sources, their diversity, incidence factors, analytical methods and prevention measures. Parasitology. 2018 Nov;145(13):1665–1699.

39. Ashrafi K, Bargues MD, O'Neill S, Mas-Coma S. Fascioliasis: a worldwide parasitic disease of importance in travel medicine. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2014 Nov-Dec;12(6 Pt A):636–49.

40. Ergönül Ö. Enfeksiyon hastalıkları epidemiyolojisi. Okmeydanı Tıp Dergisi. 2016;32(ek):1–7.

41. Ulger BV, Kapan M, Boyuk A, Uslukaya O, Oguz A, Bozdag Z, et al. Fasciola hepatica infection at a University Clinic in Turkey. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014 Nov 13;8(11):1451–5.

42. Akpınar MY, Ödemiş B, Dişibeyaz S, Öztaş E, Kılıç ZM, Kuzu UB, et al. Fasciola hepatica: tanısında endoskopik retrograd kolanjiyopankreatografi: tek merkez deneyimi. Endoskopi Gastrointestinal. 2016 Aug 8;24(2):47–50.

43. Lazo Molina L, Garrido Acedo R, Cárdenas Ramírez B, Torreblanca Nava J. Extracción endoscópica por CPRE de Fasciola hepática viva: reporte de dos casos y revisión de la literatura [Endoscopic removal by ERCP of Fasciola hepatica alive: two case reports and review of the literature]. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2013 Jan-Mar;33(1):75–81.

44. Sayilir A, Ödemis B, Köksal AS, Beyazit Y, Kayacetin E. Image of the month: Fasciola hepatica as a cause of cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 May;107(5):655.

45. Hartl S, Breyer MK, Burghuber OC, Ofenheimer A, Schrott A, Urban MH, et al. Blood eosinophil count in the general population: typical values and potential confounders. Eur Respir J. 2020 May 14;55(5):1901874.

46. Tanabe MB, Caravedo MA, Clinton White A Jr, Cabada MM. An Update on the Pathogenesis of Fascioliasis: What Do We Know? Res Rep Trop Med. 2024 Feb 13;15:13–24.

47. Frigerio S, da Costa V, Costa M, Festari MF, Landeira M, Rodríguez-Zraquia SA, et al. Eosinophils Control Liver Damage by Modulating Immune Responses Against Fasciola hepatica. Front Immunol. 2020 Sep 18;11:579801.

48. Sauerbruch T, Schierwagen R, Trebicka J. Managing portal hypertension in patients with liver cirrhosis. F1000Res. 2018 May 2;7:F1000 Faculty Rev–533.

49. Caravedo MA, Cabada MM. Human Fascioliasis: Current Epidemiological Status and Strategies for Diagnosis, Treatment, and Control. Res Rep Trop Med. 2020 Nov 26;11:149–58.

50. Wu Y, Li W, Hu Y, Liu Y, Sun X. Suppression of sirtuin 1 alleviates airway inflammation through mTOR‑mediated autophagy. Mol Med Rep. 2020 Sep;22(3):2219–26.

51. Martins IJ. Anti-aging genes improve appetite regulation and reverse cell senescence and apoptosis in Global Populations.

52. Martins IJ. Single gene inactivation with implications to diabetes and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Journal of Clinical Epigenetics. 2017 Aug 1;3(3):1–8.

53. Martins IJ. Nutrition therapy regulates caffeine metabolism with relevance to NAFLD and induction of type 3 diabetes. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2017;4(1):019.

54. Martins I. Sirtuin 1, a diagnostic protein marker and its relevance to chronic disease and therapeutic drug interventions. EC Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2018;6(4):209–15.