Abstract

Fasciolosis (fascioliasis) is an important parasitic disease of both animals and humans, caused by Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica. These liver flukes have a complex life cycle involving freshwater snails as intermediate hosts, with infection occurring through ingestion of metacercariae on contaminated vegetation or water. The disease is widely distributed, particularly in regions with wetlands or irrigated pastures that favor snail populations. Clinical outcomes range from acute liver damage during the migratory phase to chronic biliary disease, anemia, and impaired productivity in livestock. Diagnosis is based on coprological, serological, and molecular methods, with copro-antigen and antibody-based assays showing improved sensitivity. Control relies mainly on triclabendazole, although increasing drug resistance highlights the urgent need for integrated management strategies, including snail control and vaccine development. This review summarizes current knowledge on the epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, and control of fasciolosis, emphasizing recent progress and persisting challenges in both veterinary and human contexts.

Keywords

Control, Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Fasciola gigantica, Fasciola hepatica, Fasciolosis

Introduction

Fasciolosis (fascioliasis) is a parasitic disease that affects both animals and humans. It is caused by two trematode liver flukes, Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica [1–3]. F. hepatica occurs mainly in temperate regions but is also found in parts of South America, the Middle East, and Asia. F. gigantica, the major cause of tropical fasciolosis, predominates in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. Together, these parasites infect a wide range of ruminants—including sheep, cattle, goats, buffalo, and camelids—as well as non-ruminant herbivores and humans [4–6].

In livestock, fasciolosis causes significant economic losses due to mortality, reduced weight gain, lower milk yield, decreased fertility, and increased susceptibility to secondary infections [7–10]. For example, studies estimate annual global losses exceeding USD 3 billion, with high condemnation rates of infected livers at slaughter. The disease manifests in two phases. During the migratory (acute) phase, immature flukes traverse the liver parenchyma, causing hemorrhage and tissue destruction. In the biliary (chronic) phase, adult flukes inhabit the bile ducts, leading to fibrosis, cholangitis, and sometimes calcification. Clinical signs vary by stage: acute fasciolosis presents with sudden liver damage, while chronic infection is associated with anemia, hypoproteinemia, weight loss, and progressive hepatic pathology [10,13–15].

Currently, triclabendazole (TCBZ) remains the drug of choice against both immature and adult flukes, but resistance is increasingly reported worldwide [16]. The absence of an effective commercial vaccine further complicates control. Given the zoonotic importance of fasciolosis and its impact on livestock productivity, a synthesis of historical and recent research is crucial to inform prevention and management strategies. This review therefore integrates past and current knowledge on the epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and control of fasciolosis.

Review

Parasitism and its taxonomy

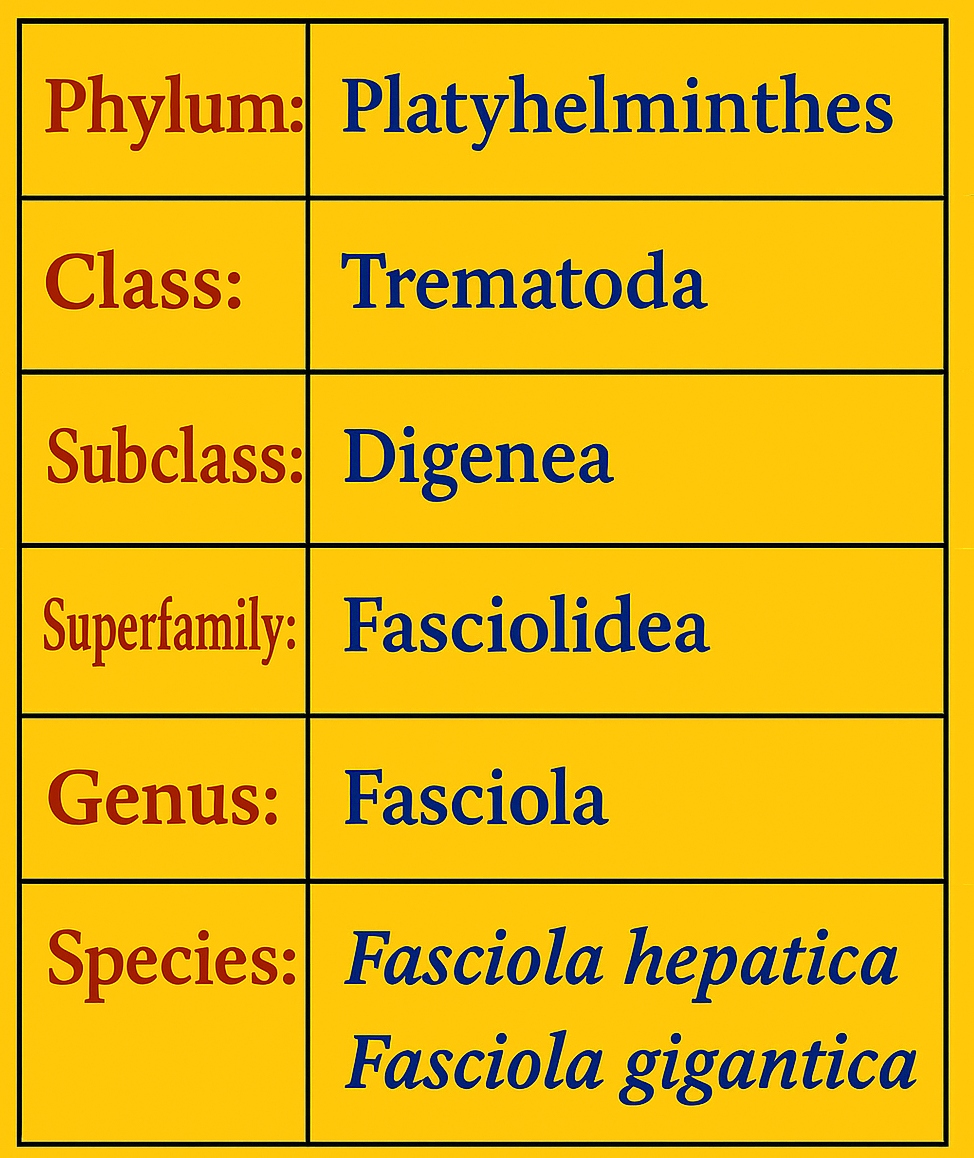

Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica are the primary species of Fasciola responsible for fasciolosis in domestic animals, particularly ruminants, owing to their indiscriminate feeding habits [17]. The taxonomic classification of the causative parasite is presented in Figure 1 [18].

Figure 1. Taxonomic Classification of Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica.

Morphology

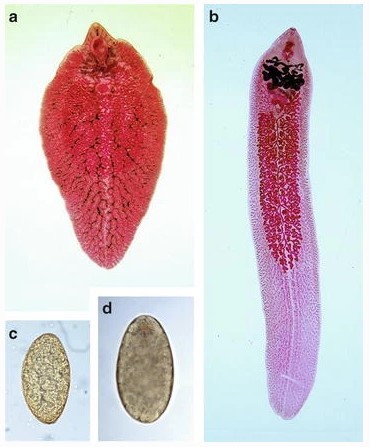

The distinct morphological characteristics of Fasciola species enable their differentiation. Fasciola hepatica (Figure 2a) has a leaf-shaped body with a broad, cone-shaped anterior projection and sharp tegumental spines. Adult flukes reach lengths of up to 3.5 cm, and their eggs (Figure 2c) measure approximately 150×90 µm, typically lacking a prominent operculum. In contrast, Fasciola gigantica (Figure 2b) is larger, measuring up to 7.5 cm in length, with a narrower shoulder, blunt posterior end, and a longer, more extensively branched ovary. Its eggs (Figure 2d) are about 190×100 µm and bear a distinct operculum [18].

Figure 2. Adult and egg morphology of Fasciola species. (a) F. hepatica shows two prominent shoulders, converging lateral margins, simple medial branches of the intestinal caeca, and a smaller body size. (b) F. gigantica lacks distinct shoulders, has parallel lateral body borders, and is larger. (c) Eggs of F. hepatica are large, ovoid, operculated, bile-stained, and unsegmented. (d) Eggs of F. gigantica are similar in appearance but larger [19].

Etiology and life cycle

Fasciolosis is caused by flukes of the genus Fasciola, commonly referred to as liver flukes [17,20]. The two primary species are Fasciola hepatica, predominant in temperate climates, and Fasciola gigantica, more common in tropical regions. In regions where their distributions overlap, hybrid forms have been reported [21,22]. Molecular techniques—particularly real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) assays targeting ITS1 rDNA, ITS2 rDNA, and 28S rDNA—are used to differentiate the genetic profiles of these species [23–25]. The epidemiological implications of hybridization and introgression remain unclear; therefore, precise and consistent use of species terminology is essential, and the names should not be used interchangeably [26].

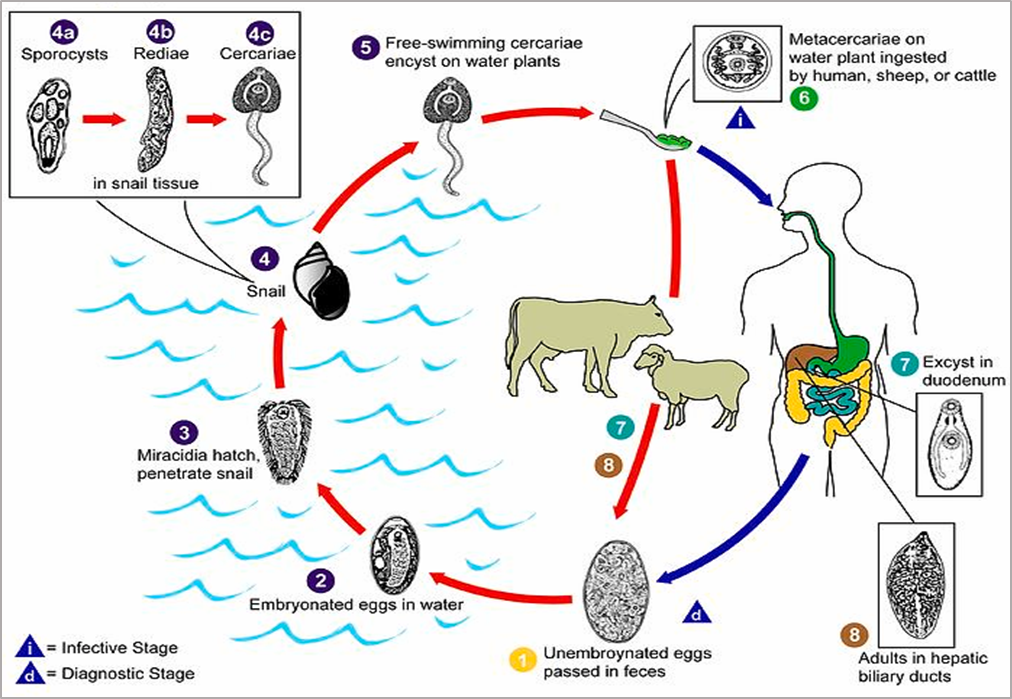

The life cycle begins when adult flukes residing in the bile ducts of the definitive host produce eggs that are excreted in feces [27]. In aquatic environments, miracidia hatch from the eggs and infect freshwater snails as intermediate hosts. Within the snail, the parasites develop sequentially into rediae and then cercariae. The cercariae emerges, encyst as metacercariae on aquatic vegetation, and are ingested by the definitive host. In the small intestine, the metacercariae excyst, penetrate the intestinal wall, migrate through the peritoneal cavity to the liver, and mature in the bile ducts approximately three months post-infection, thereby completing the cycle [11,28–30].

Prevalence and epidemiology

Fasciolosis is a globally prevalent disease [32–34]. The snail intermediate hosts typically inhabit stagnant ponds, marshes, and ditches, increasing the risk of infection for animals that graze or drink in such environments [1,35,36]. Geographical factors such as elevation, along with climatic variables including rainfall, temperature, and humidity, play key roles in the distribution and transmission of the disease. These environmental conditions directly affect the development and survival of parasite eggs and determine the distribution of snail hosts essential to the life cycle. Furthermore, improper use of anthelmintics has contributed to the emergence of drug-resistant strains, making disease control increasingly challenging. Seasonal variations in prevalence are closely associated with environmental patterns that favor parasite transmission, with rainfall and temperature fluctuations strongly influencing snail population densities [14,15,37–41].

Figure 3. Life cycle of Fasciola spp. The cycle begins when eggs are excreted in the feces of the definitive host (1), embryonate in water, and hatch into miracidia (2). The miracidia infect freshwater snails—typically Galba truncatula—serving as intermediate hosts (3) and develop sequentially into sporocysts (4a), rediae (4b), and cercariae (4c). Cercariae are released from the snail (5) and encyst on aquatic vegetation as metacercariae (6), the infective stage. After ingestion by the definitive host (7), metacercariae excyst in the small intestine, migrate to the liver (8), and mature into adult flukes within the bile ducts [31].

Clinical signs

The clinical manifestations of bovine fasciolosis vary depending on the form of the disease. Acute fasciolosis, although uncommon, can lead to sudden death and is typically associated with marked weight loss, anemia, and hypoproteinemia. Subacute cases present with anemia, jaundice, and poor body condition. Chronic fasciolosis—the most common form—is characterized by submandibular edema (“bottle jaw”) resulting from hepatic bile duct obstruction, and may occasionally be accompanied by bacillary hemoglobinuria. In the absence of re-infection, spontaneous recovery usually occurs within six months post-infection [7,42].

Transmission and pathogenesis

Fasciolosis is transmitted primarily through two routes: ingestion of herbage or hay contaminated with metacercariae, and consumption of water containing the intermediate host snails. Humans can also become infected by eating aquatic plants harboring infectious larvae or by consuming raw liver from infected animals [43]. After ingestion, the metacercariae excyst in the small intestine, and the newly excysted juveniles (NEJs) penetrate the intestinal mucosa. Within 72 hours, they can be detected in the abdominal cavity, from which they migrate across the peritoneum to the liver surface without initially producing noticeable clinical signs [44,45]. NEJs typically target the left hepatic lobe, likely due to its anatomical proximity to the duodenum and ease of access. In heavy infections, however, aberrant migration may occur, with juveniles invading other organs such as the diaphragm and lungs, leading to complications including pneumonia and fibrinous pleurisy [46].

The disease progresses through two distinct phases: the parenchymal phase and the biliary phase. The parenchymal phase begins when NEJs penetrate Glisson’s capsule and migrate through the liver parenchyma, causing mechanical injury via their spined tegument and possibly through secreted products that exacerbate tissue damage. This migration produces necrotic and hemorrhagic lesions, triggering inflammation and activating host immune responses [47]. Parasite excretory–secretory products persist within the tissue, continuing to attract immune cells and reflecting the dynamic interplay between parasite activity and host defenses [48].

The biliary phase commences when the parasites enter the bile ducts. Adult flukes inflict mechanical damage with their oral suckers while feeding on blood and surrounding hepatic tissue, sometimes ingesting macerated hepatocytes visible within the sucker or pharynx. This feeding causes epithelial erosion, trauma, and rupture of small blood vessels [44]. In addition to mechanical injury, chemical factors contribute to pathology; for instance, bile duct dilation may be associated with parasite-derived proline, an amino acid essential for collagen synthesis by fibroblasts [49–51]. The combined mechanical and chemical insults elicit marked eosinophilic and granulomatous inflammation, particularly when eggs penetrate the hepatic parenchyma [52], and induce pronounced bile duct hyperplasia [53].

Diagnosis

Traditional diagnosis of fasciolosis relies on detecting Fasciola eggs in feces or identifying specific antibodies against F. hepatica in serum. More recently, copro-antigen detection assays have been developed, offering improved sensitivity and specificity [54]. These assays, validated in both experimental infections [55] and field studies in endemic and non-endemic areas [56], enable more accurate identification of infected animals. However, most diagnostic tools in cattle remain qualitative, despite the importance of infection intensity in predicting production losses [57].

To support large-scale monitoring without disturbing animals, milk-based testing is increasingly used. The MM3-SERO Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) has demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for serodiagnosis, and bulk milk testing allows estimation of within-herd prevalence [58–60]. Immunoassays such as indirect ELISA are favored for their ability to process large sample numbers and detect antibodies early in infection, particularly during the parasite’s migratory phase. Antigens can be detected during early infection using sandwich-ELISA; however, once the parasite establishes in the bile ducts, antigen levels decline, making fecal or bile samples more suitable for detection [61].

Post-treatment, antibody levels may remain elevated for extended periods, complicating interpretation. This limitation reinforces the value of combined approaches—such as pairing indirect and direct ELISA—for more accurate assessment [42,61]. Similar immunodiagnostic strategies have been developed for F. gigantica, with validation based on sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy [10,62].

Fasciolosis is frequently associated with anemia, reflected by reduced hemoglobin levels, packed cell volume (PCV), and total erythrocyte count (TEC). Red blood cell indices and PCV values can help characterize the type of anemia. Leukocytosis—particularly eosinophilia and neutrophilia—typically indicates the host’s immune response. Biochemical indicators of hepatic damage include elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total bilirubin, and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT). Reduced serum total protein, albumin, and globulin concentrations further suggest impaired hepatic function and protein metabolism [63–69].

Necropsy remains the gold standard for confirming fasciolosis [62]. Gross lesions often include enlarged bile ducts containing adult flukes or eggs, discoloration and nodularity of the liver parenchyma, and fibrosis indicative of chronic infection. Hemorrhage and necrosis may appear as reddish-brown discoloration or focal necrotic spots. Periportal fibrosis, characterized by collagen deposition around bile ducts, contributes to a firm liver texture. Chronic inflammation can result in thick fibrous bands and adhesions between liver lobes or adjacent tissues. In severe cases, flukes may aberrantly migrate to extrahepatic sites such as the lungs or abdominal cavity, producing nodules or cystic lesions [70–78].

Microscopic examination reveals a progression from acute to chronic inflammatory changes. Early lesions are dominated by neutrophils and eosinophils, progressing to chronic inflammation with lymphocyte and macrophage infiltration. Fibrosis, with collagen deposition around bile ducts and periportal areas, is often accompanied by granuloma formation around degenerating parasites or eggs. Migration of immature flukes produces hemorrhage, necrosis, and focal lesions, while bile duct epithelium undergoes hyperplasia and hypertrophy as part of tissue repair. Long-standing inflammation and fibrosis can lead to bile stasis, cholangitis, and ultimately biliary cirrhosis, markedly impairing liver function [70,74–76,78,79].

Prevention and control

Effective prevention and control of fasciolosis require integrated strategies targeting both the parasite and its intermediate hosts [33,56,80,81]. One key approach involves eradicating snail intermediate hosts using molluscicides or biological control agents such as competitor snails like Marisa cornuarietis. Chemical molluscicides—including niclosamide and copper sulfate—can be effective when applied seasonally and in targeted habitats. However, their practical application is often limited by labor intensity, cost, environmental pollution, and rapid recolonization of snail habitats. Moreover, chemical interventions may adversely affect non-target species [81–85]. Biological control methods employing snail predators and parasites show promise but remain challenging to implement at scale [86–89].Grazing management practices that restrict animal access to contaminated pastures effectively reduce infection risk. Additionally, improving drainage in wetlands limits snail habitats and curtails their population growth [36,90,91].

Vaccine development efforts have shown potential; experimental vaccines using irradiated metacercariae or parasite extracts have induced partial resistance in ruminants. Nonetheless, commercially viable vaccines remain elusive due to challenges in efficacy and limited funding [5,92–95]. Currently, anthelmintic drugs are the primary means of treatment, targeting flukes at various life stages [96–98]. Effective chemotherapy is essential to reduce environmental contamination by interrupting egg shedding. Albendazole is commonly used in dairy herds infected with F. hepatica, offering broad-spectrum activity against gastrointestinal nematodes but with possible impacts on milk production. Oxyclozanide is effective against mature flukes older than 14 weeks [99,100], while triclabendazole remains the drug of choice due to its efficacy against all parasite stages [16]. However, widespread and indiscriminate use has led to emerging resistance, complicating control efforts. Combination therapies involving older drugs have demonstrated high efficacy against both immature and mature flukes [35,101–104].

Conclusion

Fasciolosis is a globally distributed parasitic disease affecting diverse hosts and resulting in significant economic losses. Its complex life cycle, coupled with profound impacts on liver function, underscores the challenge it poses to animal health and productivity. Advances in diagnostic techniques have improved detection and surveillance, yet control remains hindered by emerging drug resistance and environmental factors. Integrated prevention strategies—targeting snail intermediate hosts, optimizing grazing management, and advancing vaccine development—are essential for sustainable control. Addressing these challenges is critical to mitigating the burden of fasciolosis in both livestock and human populations worldwide.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

2. Behm CA, Sangster NC. Pathology, pathophysiology and clinical aspects. Fasciolosis. 1999;185:217.

3. Mas-Coma S, Valero MA, Bargues MD. Human and Animal Fascioliasis: Origins and Worldwide Evolving Scenario. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2022 Dec 21;35(4):e0008819.

4. Parkinson M, O'Neill SM, Dalton JP. Endemic human fasciolosis in the Bolivian Altiplano. Epidemiol Infect. 2007 May;135(4):669–74.

5. Spithill TW, Carmona C, Piedrafita D, Smooker PM. Prospects for immunoprophylaxis against Fasciola hepatica (liver fluke). Parasitic helminths: targets, screens, drugs and vaccines. 2012 Jul 18:465–84.

6. Zeng M, Wang X, Qiu Y, Sun X, Qiu H, Ma X, et al. Metabolomic and systematic biochemical analysis of sheep infected with Fasciola hepatica. Vet Parasitol. 2023 Jan;313:109852.

7. Abebe K, Tsegaye G. A Review on Bovine Fasciolosis. Global Veterinaria. 2021;23(3):134–41.

8. Ashrafi K, Bargues MD, O'Neill S, Mas-Coma S. Fascioliasis: a worldwide parasitic disease of importance in travel medicine. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2014 Nov-Dec;12(6 Pt A):636–49.

9. Ibrahim N. Fascioliasis: systematic review. Adv Biol Res. 2017;11(5):278–85.

10. Phiri AM, Phiri IK, Monrad J. Prevalence of amphistomiasis and its association with Fasciola gigantica infections in Zambian cattle from communal grazing areas. J Helminthol. 2006 Mar;80(1):65–8.

11. Jones RA, Williams HW, Dalesman S, Brophy PM. Confirmation of Galba truncatula as an intermediate host snail for Calicophoron daubneyi in Great Britain, with evidence of alternative snail species hosting Fasciola hepatica. Parasit Vectors. 2015 Dec 23;8:656.

12. Mehmood K, Zhang H, Sabir AJ, Abbas RZ, Ijaz M, Durrani AZ, et al. A review on epidemiology, global prevalence and economical losses of fasciolosis in ruminants. Microb Pathog. 2017 Aug;109:253–62.

13. Costa M, Saravia A, Ubios D, Lores P, da Costa V, Festari MF, et al. Liver function markers and haematological dynamics during acute and chronic phases of experimental Fasciola hepatica infection in cattle treated with triclabendazole. Exp Parasitol. 2022 Jul;238:108285.

14. Fatima M, Chishti MZ, Ahmad F, Lone BA. Epidemiological study of fasciolosis in cattle of Kashmir valley. Advances in Biological Research. 2012;6(3):106–9.

15. Rana MA, Roohi N, Khan MA. Fascioliasis in cattle-a review. JAPS: Journal of Animal & Plant Sciences. 2014 Jun 30;24(3):668–75.

16. Fairweather I. Reducing the future threat from (liver) fluke: realistic prospect or quixotic fantasy? Vet Parasitol. 2011 Aug 4;180(1-2):133–43.

17. Shafi W, Shafi W. Prevalence of bovine fasciolosis in and around Bedelle. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Res. 2021;7:13–23.

18. Soulsby EJ. Helminths, arthropods and protozoa of domesticated animals. 7th ed. Bailliere Tindall; 1982.

19. Mas-Coma S, Valero MA, Bargues MD. Fascioliasis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;766:77–114.

20. Alemu B. Bovine fasciolosis in Ethiopia-a review. Journal of Veterinary and Animal Research. 2019;2(2):202.

21. Agatsuma T, Arakawa Y, Iwagami M, Honzako Y, Cahyaningsih U, Kang SY, et al. Molecular evidence of natural hybridization between Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica. Parasitol Int. 2000 Sep;49(3):231–8.

22. Lotfy WM, Brant SV, DeJong RJ, Le TH, Demiaszkiewicz A, Rajapakse RP, et al. Evolutionary origins, diversification, and biogeography of liver flukes (Digenea, Fasciolidae). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008 Aug;79(2):248–55.

23. Marcilla A, Bargues MD, Mas-Coma S. A PCR-RFLP assay for the distinction between Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica. Mol Cell Probes. 2002 Oct;16(5):327–33.

24. Alasaad S, Soriguer RC, Abu-Madi M, El Behairy A, Jowers MJ, Baños PD, et al. A TaqMan real-time PCR-based assay for the identification of Fasciola spp. Vet Parasitol. 2011 Jun 30;179(1-3):266–71.

25. Calvani NED, Ichikawa-Seki M, Bush RD, Khounsy S, Šlapeta J. Which species is in the faeces at a time of global livestock movements: single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping assays for the differentiation of Fasciola spp. Int J Parasitol. 2020 Feb;50(2):91–101.

26. Calvani NE, Šlapeta J. Fasciola gigantica and Fasciola hybrids in Southeast Asia. In: Fasciolosis. Wallingford UK: CABI; 2021. pp. 423–60.

27. Zachary JF, McGavin MD, editors. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012.

28. Wilson RA, Pullin R, Denison J. An investigation of the mechanism of infection by digenetic trematodes: the penetration of the miracidium of Fasciola hepatica into its snail host Lymnaea truncatula. Parasitology. 1971 Dec;63(3):491–506.

29. Thomas AP. The Life History of the Liver-Fluke (Fasciola hepetica). Journal of Cell Science. 1883 Jan 1;2(89):99–133.

30. Correa AC, Escobar JS, Durand P, Renaud F, David P, Jarne P, et al. Bridging gaps in the molecular phylogeny of the Lymnaeidae (Gastropoda: Pulmonata), vectors of Fascioliasis. BMC Evol Biol. 2010 Dec 9;10:381.

31. Daramola OO. Bioinformatic analysis of Fasciola hepatica genome. The University of Liverpool (United Kingdom); 2023.

32. Maqbool A, Arshed MJ, Mahmood F. Epidemiology & Chemotherapy of Fascioliasis in Buffaloes. Assiut Veterinary Medical Journal. 1994 Jan 1;30(60):115–23.

33. Admassu B, Shite A, Kinfe G. A review on bovine fasciolosis. Eur. J. Biol. Sci. 2015;7(3):139–46.

34. Rizwan M, Khan MR, Afzal MS, Manahil H, Yasmeen S, Jabbar M, et al. Prevalence of fascioliasis in livestock and humans in Pakistan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2022 Jul 7;7(7):126.

35. Boray JC. Drug resistance in Fasciola Hepatica. In: Boray JC, Martin PJ, Rew RS, editors. Resistance of Parasites to Antiparasitic Drugs MSD. AGVET. 1990. p.151-158.

36. Fairweather I, Boray JC. Fasciolicides: efficacy, actions, resistance and its management. The Veterinary Journal. 1999 Sep 1;158(2):81–112.

37. Ollerenshaw CB. Some observations on the epidemiology of fascioliasis in relation to the timing of molluscicide applications in the control of the disease. Vet Rec. 1971 Feb 6;88(6):152–64.

38. Wamae LW, Ongare JO, Ihiga MA, Mahaga M. Epidemiology of fasciolosis on a ranch in the central Rift Valley, Kenya. Trop Anim Health Prod. 1990 May;22(2):132–4.

39. Thompson SN. Physiology and biochemistry of snail-larval trematode relationships. In: Advances in trematode biology. CRC Press; 1997. pp. 149–96).

40. Garg R, Yadav CL, Kumar RR, Banerjee PS, Vatsya S, Godara R. The epidemiology of fasciolosis in ruminants in different geo-climatic regions of north India. Tropical animal health and production. 2009 Dec;41(8):1695–700.

41. Mas-Coma S, Valero MA, Bargues MD. Fasciola and Fasciolopsis. Biology of Foodborne Parasites. 2015 Apr 6:371–404.

42. Ame MM, Mohammed A, Mohammed K. Review on ovine fasciolosis. Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. 2023;10(3):161–70.

43. Spithill TW, Dalton JP. Progress in development of liver fluke vaccines. Parasitology Today. 1998 Dec 1;14(6):224–8.

44. Dawes B, Hughes DL. Fascioliasis: the invasive stages of Fasciola hepatica in mammalian hosts. Advances in Parasitology. 1964 Jan 1;2:97–168.

45. Dow C, Ross JG, Todd JR. The histopathology of Fasciola hepatica infections in sheep. Parasitology. 1968 Feb;58(1):129–35.

46. Boray JC. Experimental fascioliasis in Australia. Adv Parasitol. 1969;7:95–210.

47. Zafra R, Pérez-Écija RA, Buffoni L, Moreno P, Bautista MJ, Martínez-Moreno A, et al. Early and late peritoneal and hepatic changes in goats immunized with recombinant cathepsin L1 and infected with Fasciola hepatica. J Comp Pathol. 2013 May;148(4):373–84.

48. Molina-Hernández V, Mulcahy G, Pérez J, Martínez-Moreno Á, Donnelly S, O'Neill SM, et al. Fasciola hepatica vaccine: we may not be there yet but we're on the right road. Vet Parasitol. 2015 Feb 28;208(1-2):101–11.

49. Isseroff H, Sawma JT, Reino D. Fascioliasis: role of proline in bile duct hyperplasia. Science. 1977 Dec 16;198(4322):1157–9.

50. Modavi S, Isseroff H. Fasciola hepatica: collagen deposition and other histopathology in the rat host's bile duct caused by the parasite and by proline infusion. Exp Parasitol. 1984 Dec;58(3):239–44.

51. Lopez P, Tuñon MJ, Gonzalez P, Diez N, Bravo AM, Gonzalez-Gallego J. Ductular proliferation and hepatic secretory function in experimental fascioliasis. Exp Parasitol. 1993 Aug;77(1):36–42.

52. Pérez J, Ortega J, Moreno T, Morrondo P, López-Sández C, Martínez-Moreno A. Pathological and immunohistochemical study of the liver and hepatic lymph nodes of sheep chronically reinfected with Fasciola hepatica, with or without triclabendazole treatment. J Comp Pathol. 2002 Jul;127(1):30–6.

53. Zafra R, Pérez-Écija RA, Buffoni L, Pacheco IL, Martínez-Moreno A, LaCourse EJ, et al. Early hepatic and peritoneal changes and immune response in goats vaccinated with a recombinant glutathione transferase sigma class and challenged with Fasciola hepatica. Res Vet Sci. 2013 Jun;94(3):602–9.

54. Abunna F, Asfaw L, Megersa B, Regassa A. Bovine fasciolosis: coprological, abattoir survey and its economic impact due to liver condemnation at Soddo municipal abattoir, Southern Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2010 Feb;42(2):289–92.

55. Cornelissen JB, Gaasenbeek CP, Borgsteede FH, Holland WG, Harmsen MM, Boersma WJ. Early immunodiagnosis of fasciolosis in ruminants using recombinant Fasciola hepatica cathepsin L-like protease. Int J Parasitol. 2001 May 15;31(7):728–37.

56. Salimi-Bejestani MR, Daniel RG, Felstead SM, Cripps PJ, Mahmoody H, Williams DJ. Prevalence of Fasciola hepatica in dairy herds in England and Wales measured with an ELISA applied to bulk-tank milk. Vet Rec. 2005 Jun 4;156(23):729–31.

57. Vercruysse J, Claerebout E. Treatment vs non-treatment of helminth infections in cattle: Defining the economic value. In: Kennedy MW, editor. Veterinary Parasitology. Elsevier; 2001. pp. 53–9.

58. Mezo M, González-Warleta M, Ubeira FM. The use of MM3 monoclonal antibodies for the early immunodiagnosis of ovine fascioliasis. J Parasitol. 2007 Feb;93(1):65–72.

59. Martínez-Sernández V, Orbegozo-Medina RA, González-Warleta M, Mezo M, Ubeira FM. Rapid Enhanced MM3-COPRO ELISA for Detection of Fasciola Coproantigens. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016 Jul 20;10(7):e0004872.

60. López Corrales J, Cwiklinski K, De Marco Verissimo C, Dorey A, Lalor R, Jewhurst H, et al. Diagnosis of sheep fasciolosis caused by Fasciola hepatica using cathepsin L enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). Vet Parasitol. 2021 Oct;298:109517.

61. Abdel-Rahman SM. Immunodiagnosis of fasciolosis by detection of coproantigen. Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College; 1996.

62. Adamu M, Wossene A, Tilahun G, Basu AK. Comparative diagnostic techniques in ruminant fasciolosis: Fecal sedimentation, indirect ELISA, liver inspection and serum enzyme activities. Ethiopian Veterinary Journal. 2019 Oct 8;23(1):42–58.

63. Ahmed MI, Ambali AG, Baba SS. Haematological and biochemical responses of Balami sheep to experimental Fasciola gigantica infection. Journal of Food Agriculture and Environment. 2006 Apr;4(2):71–4.

64. Singh P, Verma AK, Jacob AB, Gupta SC, Mehra UR. Haematological and biochemical changes in Fasciola gigantica infected buffaloes fed on diet containing deoiled mahua (Bassia latifolia) seed cake. Journal of Applied Animal Research. 2011 Sep 1;39(3):185–8.

65. Abd Ellah MR, Hamed MI, Ibrahim DR, Rateb HZ. Serum biochemical and haematological reference intervals for water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) heifers. Journal of the South African Veterinary Association. 2014 Jan 1;85(1):1–7.

66. Anita Ganguly AG, Bisla RS, Chaudhri SS. Haematological and biochemical changes in ovine fasciolosis. Haryana Vet. 2016;55:27–30.

67. El-Aziem Hashem MA, Mohamed SS. Hazard assessments of cattle fascioliasis with special reference to hemato-biochemical biomarkers. Vet Med Open J. 2017;2(1):12–8.

68. Gattani A, Kumar A, Singh GD, Tiwary R, Kumar A, Das AK, et al. Hematobiochemical Alteration in Naturally Infected Cattle With Fasciola Under Tropical Region. Journal of Veterinary Science and Technology. 2018;4:20–3.

69. Brahmbhatt NN, Kumar B, Thakre BJ, Bilwal AK. Haemato-biochemical characterization of fasciolosis in Gir cattle and Jaffrabadi buffaloes. J Parasit Dis. 2021 Sep;45(3):683–8.

70. Masuduzzaman M, Raman ML, Hossain MA. Incidence and pathological changes in fascioliasis (Fasciola gigantica) of domesticated deer. Bangladesh Journal of Veterinary Medicine. 2005;3(1):67–70.

71. Affroze S, Begum N, Islam MS, Rony SA, Islam MA, Mondal MM. Risk factors and gross pathology of bovine liver fluke infection at netrokona district, bangladesh. J. Anim. Sci. Adv. 2013;3(2):83–90.

72. Chiezey NP, Adama JY, Ajanusi OJ, Lawal IA. Distruption of estrus in the acute phase of Fascila gigantica infections in Yankasa ewes. 2013.

73. Abraham JT, Jude IB. Fascioliasis in cattle and goat slaughtered at Calabar Abattoirs. 2014.

74. Kitila DB, Megersa YC. Pathological and serum biochemical study of liver fluke infection in ruminants slaughtered at ELFORA Export Abattoir, Bishoftu, Ethiopia. Global J Med Res. 2014;14:6–20.

75. Salmo NA, Hassan SM, Saeed AK. Histopathological study of chronic livers Fascioliasis of cattle in Sulaimani abattoir. AL-Qadisiyah Journal of Veterinary Medicine Sciences. 2014;13(2):71–80.

76. Okoye IC, Egbu FM, Ubachukwu PO, Obiezue NR. Liver histopathology in bovine Fascioliasis. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2015 Aug 31;14(33):2576–82.

77. Lamb J, Doyle E, Barwick J, Chambers M, Kahn L. Prevalence and pathology of liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica) in fallow deer (Dama dama). Veterinary Parasitology. 2021 May 1;293:109427.

78. Ashoor SJ, Wakid MH. Prevalence and hepatic histopathological findings of fascioliasis in sheep slaughtered in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Sci Rep. 2023 Apr 24;13(1):6609.

79. Al-Mahmood SS, Al-Sabaawy HB. Fasciolosis: grading the histopathological lesions in naturally infected bovine liver in Mosul city. Iraqi Journal of Veterinary Sciences. 2019 Jun 1;33(2):379–87.

80. Roberts JA, Suhardono. Approaches to the control of fasciolosis in ruminants. Int J Parasitol. 1996 Aug-Sep;26(8-9):971–81.

81. Charlier J, Höglund J, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G, Dorny P, Vercruysse J. Gastrointestinal nematode infections in adult dairy cattle: impact on production, diagnosis and control. Vet Parasitol. 2009 Sep 16;164(1):70–9.

82. Crossland NO. The effect of the molluscicide N-tritylmorpholine on transmission of Fasciola hepatica. Vet Rec. 1976 Jan 17;98(3):45–8.

83. Wilson RA, Smith G, Thomas MR. Fascioliasis. In: Anderson RM, editor. The population dynamics of infectious diseases: Theory and Applications Boston, MA: Chapman and Hall. 1982. pp. 262–319.

84. Combes C. Trematodes: antagonism between species and sterilizing effects on snails in biological control. Parasitology. 1982 Apr;84(4):151–75.

85. Dalton JP, Mulcahy G. Parasite vaccines—a reality?. Veterinary Parasitology. 2001 Jul 12;98(1–3):149–67.

86. Levine ND. Integrated control of snails. American Zoologist. 1970 Nov 1;10(4):579–82.

87. Gordon HM, Boray JC. Controlling liver-fluke: a case for wildlife conservation? Vet Rec. 1970 Mar 7;86(10):288–9.

88. Pointier JP, McCullough F. Biological control of the snail hosts of Schistosoma mansoni in the Caribbean area using Thiara spp. Acta Trop. 1989 May;46(3):147–55.

89. Madsen H. Biological methods for the control of freshwater snails. Parasitol Today. 1990 Jul;6(7):237–41.

90. Osborne HG. Control of fascioliasis in sheep in the New England district of New South Wales. Australian Veterinary Journal. 1967;43:116–7.

91. Mahato SN, Harrison LJ, Hammond JA. Overview of fasciolosis an economically important disease of livestock in Nepal. Int J Food Microbiol. 2000;7:45-51.

92. Nansen P. Resistance in cattle to Fasciola hepatica induced by gamma-ray attenuated larvae: results from a controlled field trial. Res Vet Sci. 1975 Nov;19(3):278–83.

93. Piacenza L, Acosta D, Basmadjian I, Dalton JP, Carmona C. Vaccination with cathepsin L proteinases and with leucine aminopeptidase induces high levels of protection against fascioliasis in sheep. Infect Immun. 1999 Apr;67(4):1954–61.

94. Guasconi L, Serradell MC, Masih DT. Fasciola hepatica products induce apoptosis of peritoneal macrophages. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2012 Aug 15;148(3-4):359–63.

95. Toet H, Piedrafita DM, Spithill TW. Liver fluke vaccines in ruminants: strategies, progress and future opportunities. Int J Parasitol. 2014 Oct 15;44(12):915–27.

96. Srikitjakarn L. Strategic treatment of Fasciola gigantica in the northeast of Thailand. Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Livestock Production and Diseases in the Tropics. 1986;142–4.

97. Over HJ, Jansen J, Van Olm PW. Distribution and impact of helminth diseases of livestock in developing countries. Food & Agriculture Org.; 1992.

98. Webb CM, Cabada MM. Recent developments in the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of Fasciola infection. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2018 Oct 1;31(5):409–14.

99. Boray JC. Trematode infections of domestic animals. InChemotherapy of Parasitic Diseases. Boston, MA: Springer US; 1986 Mar 19. pp. 401–25.

100. Babiker AE, Osman AY, Azza AA, Elmansory YH, Majid AM. Efficacy of Oxyclozanide against Fasciola gigantica Infection in sheep under Sudan condition. Sudan J Vet Res. 2012;27:43–7.

101. Overend DJ, Bowen FL. Resistance of Fasciola hepatica to triclabendazole. Aust Vet J. 1995 Jul;72(7):275-6.

102. Oliveira DR, Ferreira DM, Stival CC, Romero F, Cavagnolli F, Kloss A, et al. Triclabendazole resistance involving Fasciola hepatica in sheep and goats during an outbreak in Almirante Tamandare, Paraná, Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2008 Sep;17 Suppl 1:149–53.

103. Olaechea F, Lovera V, Larroza M, Raffo F, Cabrera R. Resistance of Fasciola hepatica against triclabendazole in cattle in Patagonia (Argentina). Vet Parasitol. 2011 Jun 10;178(3-4):364–6.

104. Sanabria R, Ceballos L, Moreno L, Romero J, Lanusse C, Alvarez L. Identification of a field isolate of Fasciola hepatica resistant to albendazole and susceptible to triclabendazole. Vet Parasitol. 2013 Mar 31;193(1-3):105–10.