Abstract

Communication is essential to quality of life, linked to social interactions, employment, and independence. Verbal communication is judged using speech intelligibility, or how well a speaker is understood. When communication is negatively impacted it affects every aspect of an individual's life resulting in smaller social networks, fewer positive interactions, and higher levels of loneliness. This study investigated communication and speech intelligibility in individuals who had previously been treated for cancer. Using a survey to obtain demographic, medical, and patient-reported outcomes, cancer survivors reported the perceived effect of their cancer diagnosis had on their overall communication and the speech-language pathology services they received. Fourteen participants provided speech samples, including the Speech Intelligibility Test phrases and sentences portions. Survey data was analyzed for frequencies and descriptions while unfamiliar listeners provided speech intelligibility ratings. Results demonstrated that participants with cancer in the head and neck region displayed diminished speech intelligibility. Less than half of the participants reported receiving services to support communication and speech. These preliminary data support the need for further research in communication and cancer survivorship. These data align with previous research that suggests cancer survivors, and more specifically head and neck cancer, require speech-language pathology services acutely and throughout survivorship.

Keywords

Cancer survivorship, Speech intelligibility, Communication, Patient-reported outcomes, Rehabilitation

Introduction

Communication is an essential aspect to individuals' everyday lives as it provides a method of conveying wants, needs, thoughts, and emotions. Verbal communication is a complex process which engages the articulatory, auditory, nervous, phonatory, and respiratory systems [1]. These systems must work quickly and precisely in harmony to effectively execute the communicative intent. One way an individual’s verbal communication ability is judged is the evaluation of their speech intelligibility. Speech intelligibility describes how comprehensible an individual's speech is to a listener and/or communication partner. Disruption to the process of verbal communication can lead to decreased speech intelligibility. Reduced speech intelligibility serves as a barrier to employment, education, and social communication [2], affecting self-image and overall quality of life.

Cancer Effects on Communication and Quality of Life

Over 20 million new cancer diagnoses are made annually worldwide [3]. Individuals with a medical diagnosis, such as cancer, have a heightened need for successful communication to actively participate in their care. Unfortunately, cancerous tumors, as well as cancer treatments, can affect the anatomical structures and physiological functions necessary for speech [4,5]. While there are many types of cancer that may result in communication deficits, two of the most common include head and neck cancer, and brain tumors. Research exploring communication and head and neck cancer has concluded differences in vocal quality (e.g., roughness, breathiness), limited speech and articulation, and an overall decrease in communication either acutely or long-term [6,7]. The brain is the control center of the body, supporting all the necessary body systems for communication. Reports suggest that one in five people diagnosed with a brain tumor experience communication deficits [8]. These communication difficulties can be more obvious, based on location (i.e., tumor location in motor speech portion of brain), or less obvious (i.e., tumor location in area inhibiting respiration, which is necessary for verbal communication). Treatment of brain tumors can also leave the individual subject to communication impairments as surgery may cut into or remove vital structures, the radiation field may leave areas damaged, and chemotherapy, with its endless reaching, has the potential to sterilize pathways.

Furthermore, previous research commonly notes that communication difficulties resulting from cancer and its treatment can lead to mental health difficulty (e.g., anxiety, depression) and a decrease in quality of life. Specifically, individuals with cancer have reported aphonia or voicelessness, resulting in dependence on others to communicate on their behalf, and their communication difficulties having a negative impact on their social and professional lives, leaving them feeling unable to participate in activities and experiencing isolation [6,9-11]. In a cross-sectional study completed by Adamowicz and colleagues [12] it was determined that cancer survivors living in rural areas reported more challenges and less support. A different study conducted by Sauder and colleagues [9] noted individuals with lower education levels, who were unemployed, and/or with lower health literacy demonstrated limited communicative participation and decreased quality of life. Both investigations highlight the significant role demographics can play in cancer survivorship. Outside of communication but utilizing similar body systems and therefore also routinely linked during investigations is swallowing. Again, with a substantial portion of the existing data coming from the head and neck cancer population, disruptions in swallowing have also been noted to coexist with cancer diagnoses as well as negatively affect quality of life [6,11,13]. The number of cancer survivors is on the rise and expected to continue to increase in part to the advancements in prevention, early detection, and treatment. This statistic, along with results from previous research, help accentuate the importance of addressing communication in cancer care [14].

The purpose of the current investigation was to explore the effect of cancer and its treatments on communication and speech in cancer survivors. Patient-report in addition to validated tools were utilized. Specifically, we aimed to address speech intelligibility in cancer survivors, the patient-perceived impact cancer and its treatments had on communication and speech, and the rehabilitation support that was received to support communication and speech.

Methods

Participants were recruited via social media postings (e.g., X/Twitter, Facebook), flyers, and through contact with facilities that treat this population. To be included in the study, participants were required to be 18 years of age or older, have access to technology that allowed for participation, adequate vision to see communication prompts or adequate hearing to hear research personnel prompts, diagnosis of cancer at some point during life, and speak American English as this was the version of the standardized protocols being utilized. Potential participants were excluded from the study if they were under the age of 18 years old, were unable to access technology that allowed for participation, had never received a diagnosis of cancer, and/or did not have the necessary vision, hearing or American English skills to participate in the procedures. Procedures were approved by the University of Missouri-Columbia institutional review board. Flyers and electronic postings contained a QR code which potential participants could access to learn more about the study including the consent form. If a potential participant contacted the research personnel directly information was provided via phone or email with a follow-up, as necessary, to provide access to the electronic consent form.

Participants

Twenty-five individuals who had previously been diagnosed and treated for cancer consented to participate in this study. The average age for the participant group was 60.25 years. Sex of participants was a close distribution with 56% being male and 44% being female. More information regarding participant demographics can be found in (Table 1).

|

Variable |

Count (%) |

|

Age (Years) |

M=60.25, SD=13.58 |

|

Sex |

Male=14 (56%) Female=11 (44%) |

|

Education |

HS Diploma/Equivalent=5 (20%) Some college=5 (20%) Associate degree=1 (4%) Bachelor’s degree=8 (32%) Graduate degree=3 (12%) Post-graduate degree=3 (12%)

|

|

Occupation |

Employed=13 (52%) Unemployed=2 (8%) Disabled=2 (8%) Retired=8 (32%) |

|

Time Since Diagnosis (Year) |

M=6.87 |

|

Cancer Diagnosis |

Laryngeal=9 (36%) Oral=2 (8%) Oropharyngeal=7 (28%) Thyroid=4 (16%) Other=3 (12%) |

|

Cancer Treatment |

Surgery=15 (60%) Laryngectomy=6 Thyroidectomy=4 Other=5 Radiation=21 (84%) Chemotherapy=14 (56%) |

Patient-reported outcomes

Electronic surveys were administered via REDCap software. The survey, containing 37 questions, was designed by the authors to obtain demographic information, cancer and cancer treatment history, participant perception regarding communication and speech, and information about speech-language pathology services received.

A total of 13 questions were closed-ended or text box completion directed at obtaining demographic information such as age, sex, geographic location, education, occupation, and current medical history. Nine questions pertaining to cancer diagnosis and treatment followed the demographic questions. These questions were mainly closed-ended with opportunities to provide more information, as necessary. For example, one question posed to participants included, Did you receive radiation as part of your cancer treatment? If the participant responded yes, they were directed to a follow-up, text box completion question to Please explain (how many weeks, after surgery, same time as chemotherapy, etc.). The survey included two visual analog scales to gather information on the patient-reported impact on communication and speech. Visual analog scales were used because they have been shown to be reliable measures of subjective information in healthcare fields such as speech-language pathology [15]. Participants were asked to move a cursor along a line that was bookended on the left with Not at all and on the right with A lot to respond to the following two prompts, To what degree has your cancer affected your speech and To what degree has your cancer affected your overall communication. Upon providing a response on the visual analog scale, participants were provided a text box to further explain and provide details. Three questions regarding speech-pathology services related to communication and speech, and the use of any communication assisted devices were included. Three questions regarding swallowing issues and speech-pathology services related to swallowing were also posed. The final five questions of the survey asked participants if they were interested in completing a follow-up virtual data collection session via Zoom where speech samples would be collected. If interest was indicated, along with adequate technology, vision, and/or hearing, participants were asked to provide their availability (e.g., evenings, only Mondays and Wednesday) to support the research personnel in scheduling.

Survey data were extracted, and complete responses were analyzed by calculating the proportion of each response to all responses and reported using a percentage, where appropriate.

Speech sample

Fourteen participants consented to participation in a virtual data collection session that included obtaining a speech sample. Of the participants that provided a speech sample, 64% identified as males and 36% identified as females. The mean age of this group was 61 years, with a range from 36 years-80 years. All but three of these participants received a cancer diagnosis for a type of head and neck cancer. The average time since cancer diagnosis for this group was 10 years, with a range from 2-30 years.

Speech samples were obtained during a during HIPAA-compliant Zoom sessions and recorded for future analysis. Loopback software was used to pass audio between applications onto the computer recording the session to support the filtering of sound and noise. Each participant was shown a screen that contained prompts from the Speech Intelligibility Test phrases and sentences portions [16]. The Speech Intelligibility Test, which has been used for more than two decades in both clinical and research work, is a combination of intelligibility assessments that were extensively utilized on numerous populations including cancer [17,18]. One prompt was provided at a time with the research personnel processing through the prompts at a pace suitable for each participant. During the phrase portion participants were directed to say ten words, each within the carrier phrase, “Say ___ again.” Additionally, participants read aloud ten sentences of varying length and complexity. After speech samples had been obtained, recordings were split into individual audio files, organized using a unique participant identifier, and saved within the participant’s file.

Twelve college-age women ranging in age from 18-21 years who were non-familiar listeners and did not actively participate in any other part of this study served raters for the Speech Intelligibility Test. Speech samples were randomized to raters with each audio file being rated by three different individuals. All ratings were provided in a quiet environment using Apple Air Pod Pros. Raters were permitted to listen to each file twice, totaling approximately 30 minutes per rater session. For the phrases section, raters received a scoring sheet with seven options: the target word, five similar words, and ‘cannot decide.’ Raters were instructed to circle the most appropriate option. For the sentences section, raters were provided with a piece of paper and instructed to write all comprehensible words, even if the entire sentence could not be understood. Ratings were tallied and an intelligible percentage was calculated. Rater reliability was investigated and determined to be greater than 90% on both the phrase and sentence portions.

Results

Patient-reported outcomes

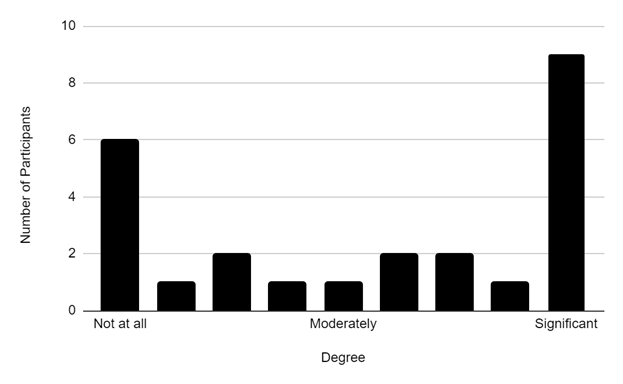

To what degree has your cancer affected your speech: Results demonstrate approximately three-quarters of participants reported their speech being affected to some degree, with 60% of participants providing a rating of 50 or greater on a 100mm visual analog scale. The group mean was 57.2, SD=41.9 (range=0-100). Figure 1 represents the frequency of responses provided with the most prevalent response being 100, from 36% of the participants.

Figure 1. Frequency of responses regarding affected speech. Participant responses to the prompt ‘To what degree has your cancer affected your speech.’ The number of participants is shown on the y-axis with their corresponding agreement on the x-axis. Results demonstrate greater responses at each end, not at all and significant.

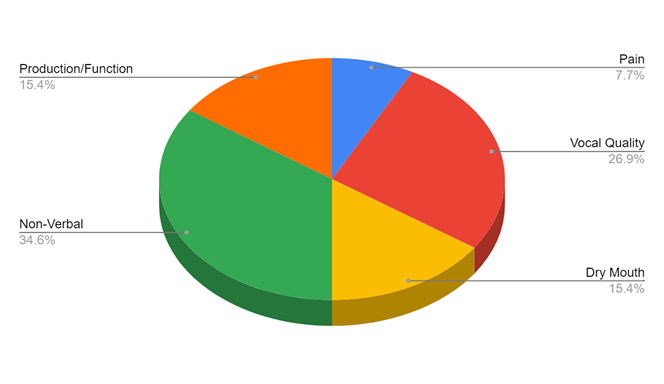

Responses from the text box completion were distributed into five main categories: production/function, vocal quality, pain, non-verbal, and dry mouth (Figure 2). The most common responses, 34.6%, fell into the non-verbal category with participants reporting they “could no longer speak” and “no speech.”

Figure 2. Frequency of category responses to specially how speech was affected. Participant written categorized responses to the prompt ‘To what degree has your cancer affected your speech.’ These responses were provided to further explain the rating response (Figure 1). Participants noted the loss of verbal communication and changes in their vocal quality as main factors.

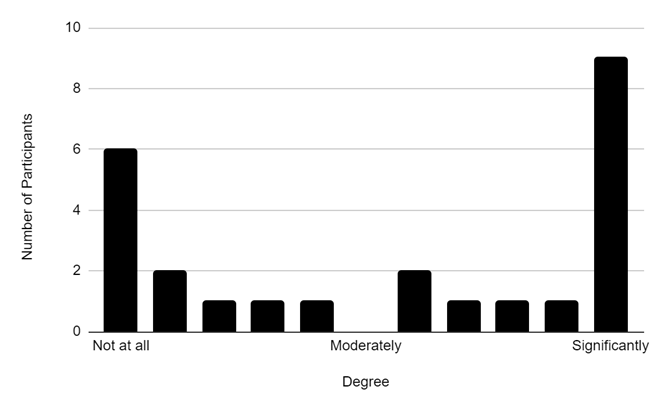

To what degree has your cancer affected your overall communication: Similar to speech, results demonstrate approximately three-quarters of participants reported their overall communication being affected to some degree, with 56% of participants providing a rating of 60 or greater on a 100mm visual analog scale. The group mean was 54.8, SD=43.1 (range=0-100). Figure 3 represents the frequency of responses provided with the most prevalent response being 100, from 36% of the participants.

Figure 3. Frequency of responses regarding affected overall communication. Participant responses to the prompt ‘To what degree has your cancer affected your overall communication.’ The number of participants is shown on the y-axis with their corresponding agreement on the x-axis. Results demonstrate greater responses at each end, not at all and significant.

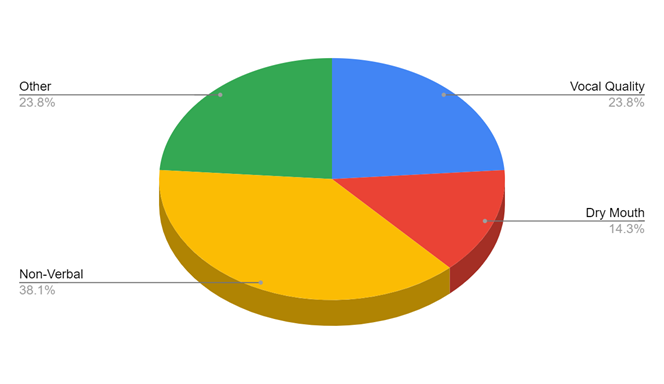

Responses from the text box completion providing specifics on the effect on overall communication were divided into four main categories: vocal quality, non-verbal, dry mouth, and other (Figure 4). The most common responses, 38.1%, once again fell into the non-verbal category with participants reporting things such as they “stopped communicating with others altogether.” Vocal quality (e.g., hoarseness, no longer able to hold a tune) and Other (e.g., chemo brain, it is very difficult to communicate with others, loss of job and taken away only source of making money) received the same number of responses.

Figure 4. Frequency of category responses to specially how overall communication was affected. Participant written categorized responses to the prompt ‘To what degree has your cancer affected your overall communication.’ These responses were provided to further explain the rating response (Figure 3). Participants noted the loss of verbal communication as the main factor but also reported changes in their vocal quality and other items (loss of income, cognition).

Speech-language pathology services and related identified areas: Results demonstrated that less than half, 40%, of participants reported receiving speech-language pathology services to support speech and communication, while slightly fewer, 36%, reported receiving services related to swallowing. Eight participants reported utilizing a device to support their communication including a type of application on their phone (e.g., text to speech) or an alaryngeal device (e.g., electrolarynx, tracheoesophageal speech). Most notably, however, is that 64% of participants reported experiencing swallowing issues at the time of data completion.

Speech intelligibility

Speech intelligibility ratings for individual participants are in Table 2. Overall, the group mean was 89% for the phrases section and 80% for the sentence section.

|

Participant |

Phrases |

sentences |

|

1 |

40% |

3% |

|

2 |

100% |

92% |

|

3 |

90% |

87% |

|

4 |

73% |

44% |

|

5 |

73% |

56% |

|

6 |

96% |

98% |

|

7 |

93% |

63% |

|

8 |

100% |

89% |

|

9 |

100% |

99% |

|

10 |

96% |

96% |

|

11 |

100% |

100% |

|

12 |

96% |

96% |

|

13 |

96% |

98% |

|

14 |

93% |

98% |

Given the previous research conducted around head and neck cancer, speech intelligibility data was divided into two groups, participants with head and neck cancer and those with a cancer diagnosis outside of the head and neck region, for further investigation. The mean speech intelligibility ratings for both sections of the Speech Intelligibility Test were lower for participants with head and neck cancer (phrases: 87%, 97%; sentences: 75%, 98%). Participants with a cancer diagnosis outside of the head and neck region scored above 95% on both Speech Intelligibility Test sections.

Discussion

Communication has a direct link to quality of life. It is also essential for active participation in one’s activities of daily living and healthcare. The purpose of this study was to examine communication and speech intelligibility in individuals who had previously been treated for cancer. Participants reported varying degrees of impact on their communication and speech. Of note is that three participants diagnosed with laryngeal cancer rated the effect on their speech and overall communication to be 100. These same participants also had some of the lowest ratings on the Speech Intelligibility Test. These findings are similar to a previous study investigating head and neck cancer which concluded that lower intelligibility ratings were associated with decreased quality of life [19]. Six participants diagnosed with non-head and neck cancer reported having no difficulties or effect on their speech and communication. The combination of these results demonstrates the potential influence cancer region and treatment has on communication and speech. These findings align with previous research that concluded the cancer site was associated with the type of speech function impairment [20]. While participants did report their speech and communication being directly affected (e.g., not being able to say certain sounds, vocal quality), participants also reported their diminished or inability to communicate caused them to lose their job, affecting their source of income. As employment is another highly linked variable to quality of life in adults it should not go without mentioning that these participants are now identifying two quality of life areas (communication and employment) that are negatively affected by their cancer and cancer treatment. These findings align with previous research that linked objective deficits to concerns in areas such as communication, eating, and social-emotional [19]. Further investigations exploring and understanding quality of life and specific attributed variables in individuals with cancer, both acute and long-term, are needed. This is particularly pertinent as mental health rates increase nationwide, particularly among individuals diagnosed with cancer and cancer survivors.

Half of the participants who provided speech samples reported receiving speech-language pathology services to support speech and/or overall communication. Interestingly, these seven samples compromised the lower two-thirds of the speech intelligibility ratings. While there were participants with head and neck cancer with high speech intelligibility ratings, as a group these participants were rated lower than individuals with other cancer diagnoses. Every participant who received a head and neck cancer diagnosis over ten years ago reported receiving speech-language pathology services. However, less than half of the participants with a head and neck cancer diagnosis within the last decade reported receiving speech-language pathology services. Given the recent advancements in head and neck cancer care and rehabilitation, this highlights the potential lack of speech-language pathologists trained or available to support this population. Of the participants who reported receiving speech-language pathology services many noted that these were provided acutely and during their inpatient hospital stay. Furthermore, of the participants with head and neck cancer who reported receiving speech-language pathology services, only one reported such services being currently active. Likewise, the participant with the lowest speech intelligibility ratings reported not receiving speech-language pathology services. This highlights the need for continued research and education around cancer survivorship and the long-term communication needs of individuals diagnosed with cancer. Lastly, only six of the 64% of participants currently experiencing swallowing issues reported receiving swallowing related support either currently or in the past. Similar to communication, this was noted as an interesting finding given the increased focus of research on swallowing and the impact swallowing has on health.

The authors recognize the limitation of a small sample size within the current investigation. Future studies should include more participants which will allow for further analysis of factors including geographical region and cancer treatment. One suggestion for future research that can enhance analysis and also increase sample size is to expand protocol use beyond American English. While the participants in the current study were only required to have American English communication skills that allowed for participation within the procedures, incorporation of more versions of the protocols would support an increased sample size. Another limitation acknowledged in this study is the use of participant self-reporting. Given that some of the participants underwent medical treatment more than a decade ago, and that their cancer treatment and aging could have affected their recall, participant recall must be noted as a limitation. Future investigations should consider either use of medical records to verify participant report and/or include an interview portion that allows for recall checking and follow-up questions.

Clinical implications

The field of speech-language pathology has a main purpose of supporting individuals with communication and swallowing impairments. The field is divided into nine categories which encompass communication, speech, language, cognition, communication modalities and swallowing, among others. Data from this, and previous investigations, note the difficulties within these areas faced by people diagnosed with cancer. While more research is needed, there is some evidence to support that these needs extend well into cancer survivorship care and potentially are life-long. To support this growing population, it is imperative that speech-language pathologists receive the necessary education and skill development to provide both acute and long-term services to individuals diagnosed with cancer. This could include courses and clinical training within academic programs, continuing education courses for current professionals, and access to mentoring from professionals currently providing services to support those new to the area.

Conclusion

Cancer and cancer treatment can significantly affect speech and overall communication. Studies demonstrate that communication is linked to quality of life as well as vital quality of life variables such as employment. Communication impairments have been linked to depression, anxiety, loneliness, and decreased quality of life. More information from people with cancer that directly affects the body systems involved in verbal communication, or that results in cancer treatment that involves the body systems involved in verbal communication is needed. Also needed is access to speech-language pathology services by individuals with cancer to support their needs both acutely and through survivorship.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript to disclose.

References

2. Coppens-Hofman MC, Terband H, Snik AF, Maassen BA. Speech Characteristics and Intelligibility in Adults with Mild and Moderate Intellectual Disabilities. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2016;68(4):175-82.

3. World Health Organization. Global cancer burden growing, amidst mounting need for services. 2024. https://www.who.int/news/item/01-02-2024-global-cancer-burden-growing--amidst-mounting-need-for services#:~:text=The%20IARC%20estimates%2C%20based%20on,women%20die%20from%20the%20disease, amidst mounting need for services

4. Grusdat NP, Stäuber A, Tolkmitt M, Schnabel J, Schubotz B, Wright PR, et al. Routine cancer treatments and their impact on physical function, symptoms of cancer-related fatigue, anxiety, and depression. Support Care Cancer. 2022 May;30(5):3733-44.

5. Nia HT, Munn LL, Jain RK. Physical traits of cancer. Science. 2020 Oct 30;370(6516):eaaz0868.

6. Grattan K, Kubrak C, Caine V, O'Connell DA, Olson K. Experiences of Head and Neck Cancer Patients in Middle Adulthood: Consequences and Coping. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2018 Mar 15;5:2333393618760337.

7. Nund RL, Rumbach AF, Debattista BC, Goodrow MN, Johnson KA, Tupling LN, et al. Communication changes following non-glottic head and neck cancer management: The perspectives of survivors and carers. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2015 Jun;17(3):263-72.

8. The Brain Tumour Charity. (n.d.). Communication difficulties. https://www.thebraintumourcharity.org/living-with-a-brain-tumour/side-effects/communication-difficulties/

9. Sauder C, Kapsner-Smith M, Baylor C, Yorkston K, Futran N, Eadie T. Communicative Participation and Quality of Life in Pretreatment Oral and Oropharyngeal Head and Neck Cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021 Mar;164(3):616-23.

10. Sharpe G, Camoes Costa V, Doubé W, Sita J, McCarthy C, Carding P. Communication changes with laryngectomy and impact on quality of life: a review. Qual Life Res. 2019 Apr;28(4):863-77.

11. Rathod S, Gupta T, Ghosh-Laskar S, Murthy V, Budrukkar A, Agarwal J. Quality-of-life (QOL) outcomes in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) treated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) compared to three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT): evidence from a prospective randomized study. Oral Oncol. 2013 Jun;49(6):634-42.

12. Adamowicz JL, Christensen A, Howren MB, Seaman AT, Kendell ND, Wardyn S, et al. Health-related quality of life in head and neck cancer survivors: Evaluating the rural disadvantage. J Rural Health. 2022 Jan;38(1):54-62.

13. Wu YS, Lin PY, Chien CY, Fang FM, Chiu NM, Hung CF, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with head and neck cancer: 6-month follow-up study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016 Apr 27;12:1029-36.

14. National Cancer Institute. Cancer statistics. 2024. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/statistics

15. Baylis A, Chapman K, Whitehill TL; The Americleft Speech Group. Validity and Reliability of Visual Analog Scaling for Assessment of Hypernasality and Audible Nasal Emission in Children With Repaired Cleft Palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2015 Nov;52(6):660-70.

16. Dorsey M, Yorkston K, Beukelman D, Hakel M. Speech intelligibility test for windows. Institute for Rehabilitation Science and Engineering at Madonna. 2007.

17. Yorkston KM, Beukelman DR. Communication efficiency of dysarthric speakers as measured by sentence intelligibility and speaking rate. J Speech Hear Disord. 1981 Aug;46(3):296-301.

18. Yorkston KM, Beukelman DR, Traynor C. Assessment of intelligibility of dysarthric speech. Austin, TX: Pro-ed; 1984.

19. Meyer TK, Kuhn JC, Campbell BH, Marbella AM, Myers KB, Layde PM. Speech intelligibility and quality of life in head and neck cancer survivors. Laryngoscope. 2004 Nov;114(11):1977-81.

20. McKinstry A, Perry A. Evaluation of speech in people with head and neck cancer: a pilot study. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2003 Jan-Mar;38(1):31-46.