Abstract

Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) are endocrine disruptors that may act as thyroid hormone (TH) analogues/antagonists to alter the homeostasis of the thyroid axis. Recently, we have shown that perinatal exposure to Aroclor 1254 (A1254), a commercial mixture of more than 90 PCB congeners, leads to sex-specific changes of the thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) mRNA synthesis in hypophysiotropic neurons of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN), and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) serum levels in adult rats. As opposed to males, females showed no modifications in gene expression of hypophysiotropic TRH, but serum TSH significantly increased with respect to controls. To examine whether this central interference could be ascribed to specific PCB congeners, Sprague Dawley pregnant dams received 10 mg/kg of a mixture of PCB 138, 153, 180, and 126 every day from E10 to E19, and the same dose twice a week from P1 to P21 while breastfeeding. Both in post-weaned and adult female rats, serum levels of free 3,5,3´-triiodo-L-thyronine and free L-thyroxine remained unchanged with respect to controls. However, in adult females the perinatal treatment significantly increased the integrated optical density of immunoreactive (IR)-TRH prohormone (pro-TRH) in the median eminence (ME), decreased that of IR-TH receptor (THR)-β1 in hypophysiotrophic PVN neurons, and reduced percentage and number of IR-TSH cells in the anterior pituitary. We concluded that accumulation of pro-TRH in the ME was compatible with a reduced release of TRH; this reduction contributed to impair the survival of pituitary TSH cells, and less THR- β1 in the PVN was “compensated” by unchanged THR-α1 and - β2, yielding a stable amount of pro-TRH in the PVN. Collectively, our morphofunctional results suggest that perinatal exposure of female rats to PCBs induces an inadequate adaptation of the TRH-TSH axis in the adulthood, likely leading over time to central hypothyroidism.

Keywords

Endocrine disruptor, TRH, TSH, Central hypothyroidism

Introduction

Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) are industrial chlorinated-halogenated organic chemicals widely used as dielectric fluids or flame retardants due to their inexpensive production cost [1]. However, PCBs are environmental pollutants resistant to metabolic degradation and bio accumulative, causing adverse effects in prenatal, neonatal, young, adult, and aged humans and wildlife [2-4]. Exposure can occur by a number of modalities including inhalation, ingestion, drinking, and skin or eye contact [2,3,5]. They can cross the placental and blood-brain barriers, are found in the blood and breast milk of mothers in proportion to the amount of exposure [6], and are highly transferred through mother’s milk to infants [7]. As lipophilic compounds, PCBs can accumulate in human and animal adipose tissues and be released in circulation during periods of prolonged weight loss like pregnancy-lactation and stress. They can also be absorbed and retained in plastic biomaterials like polyethylene and polystyrene [8] widely used in surgical implants and prosthesis, catheters, and medical tubings giving rise to a reservoir of PCBs potentially releasable as micro plastics in the human body [9]. As a result, PCBs may alter the microanatomy of developing neuroendocrine pathways and give rise to various endocrine derangements in adult life, becoming a paradigm of endocrine disruptors (EDs) [7,10].

Currently, it is well recognized that PCBs can interfere with the activity of thyroid hormone (TH) at various levels [11-13]. In rodents, perinatal or adult exposure to Aroclor 1254 (A1254), a commercial mixture of more than 90 PCB congeners, or to some of its more potent components may reduce free L-thyroxine (FT4) in the presence of inappropriately normal or slightly elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) plasma levels, and decrease total L-thyroxine (T4) while increasing plasma reverse 3,5,3´-triiodo-L-thyronine (rT3), hepatic glucuronidation, sulfation, and biliary elimination of T4 [13-16]. In contrast, T3 and free T3 may remain normal [15,16]. In humans, these effects are consistent with either a non-thyroidal illness (NTI) syndrome [17] or central hypothyroidism (cHYPO) [18,19].

However, in pup rats A1254 may also decrease T3 and synthesis of TH-associated thyroid and hepatic proteins including iodothyroidine 5-deiodinase type 1 (D1) [20], whereas in the hypothalamus of adult animals, PCB 153 may reduce the expression of mRNA for thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) and TSH receptors, and that for deiodinases type 2 and 3 (D2, D3) [13]. In contrast, perinatal administration of A1254 does not affect adult D2 activity in both sexes [21]. Finally, PCBs and their metabolites are structurally related to T3 and T4 [11], can bind to TH receptors (THRs) [7,11,22] in a non-competitive manner [23,24] and may displace THs from their serum transport proteins [25,26]. Thus, acting as biphenyl TH analogues/antagonists, PCBs disrupt central and/or peripheral effects of THs [12,27].

Recently, we have shown that perinatal exposure to A1254 hampers the adult rat, TRH-TSH axis in a sex-specific manner. As opposed to males, females had no changes in TRH gene expression in the PVN, whereas an increase in TSH secretion was observed. This response suggested an alteration of their TRH-TSH axis in the adult life [28]. Since A1254 comprises an enormous number of PCB congeners, we decided to shed light on possible changes in selective components of the female rat, TRH-TSH axis in relation to specific PCBs. We used a mixture of the three most prevalent, heavily chlorinated, non-dioxin-like PCB congeners (noncoplanar 138, 153, 180) and the most potent dioxin-like PCB (coplanar 126) present in humans and wildlife, perinatally administered in a proportion similar to that found in the environment [29,30]. Then, in adult females we immunocytochemically and morphometrically dissected out effects on TRH neurons and THRs-a1, -b1, and -b2 in the hypothalamic tuberoinfundibular axis, and on thyrotrophes in the anterior pituitary, revealing a morphofunctional derangement compatible with cHYPO.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

In all experiments, the PCB mixture used was composed of two hexachlorobiphenyls (PCB138 and PCB153), one heptachlorobiphenyl (PCB180) and one coplanar pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB 126). All these compounds (purity 100%) were supplied by Chemical Research 2000 (Rome, Italy). PCB 138, 153, and 180 represented one third of the total mixture, whereas PCB 126 was added to the mixture in a 1/104 ratio. The dose and route of administration used in the present study has been reported as disruptive for the thyroid hormone homeostasis, in a dose range out of lethality [13,30].

Experimental groups

Administration of the PCB mixture (138, 153, 180 and 126) to Sprague Dawley dams (n=5), was given from mid-pregnancy [E15-E19 (Embryonic); 10 mg/kg/day subcutaneously, dissolved in 0.1 ml peanut oil and then left to deliver spontaneously] to the end of lactation [PND1-PND21 (PND, Postnatal day); 10 mg/kg twice a week subcutaneously as above]; control dams (n=5), received 0.1 mL corn oil (vehicle). In accordance with a recent report [31], this PCB mixture did not reduce litter size from PND1 to PND21 (average pups / litter = 11-15). Thus, female pups were separated after this time lag (four rats/cage) for further analysis (n=38 control females, n= 23 PCB-treated females). Control-PND21 and PCB-PND21 pups were allowed to survive 5 more weeks, after which brains and pituitaries were removed and prepared for immunocytochemistry (ICC).

Animals

Sprague Dawley rats (2 months old), were maintained under controlled laboratory conditions with a light-dark cycle (lights between 07:00 h and 19:00 h), in a room with controlled temperature (25 ± 1 °C) and ad libitum access to tap water and regular diet at the vivarium of the University of Parma, Parma, Italy. All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee for Animal Use in Research of the University of Parma, Parma, Italy and in accordance with the guidelines of the European Union and Italian Ministry of Health (approval code 18/2016-PR).

Tissue processing for light microscopic ICC

Light microscopic (LM) ICC of pro-TRH in the PVN and ME, THR-a1, -b1, and -b2 in the PVN, and TSH in the anterior pituitary were performed on free-floating sections, using a method previously described [32]. Briefly, following deep anesthesia with intraperitoneal (i.p) Zoletil (50 mg/kg), animals were perfused through the left heart ventricle with anticoagulant (30s of 0.1 M Phosphate-Buffered Saline-PBS + 10,000 U/L heparin sodium at 37 °C), followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA)-0.2% glutaraldehyde in PBS at 4°C under continuous positive pressure for 20 min. Brains and pituitaries were post-fixed in 4% PFA in PBS at 4°C for 2-3 h, and sectioned coronally at 40 microns on a Lancer Vibratome. After washing, brain tissue sections were processed using well-characterized polyclonal rabbit antisera (Ab) to pre-pro-TRH178-199, recognizing the 2.6 kDa peptide characteristic of pre-pro-TRH178-199 [33], THR-a1, recognizing the carboxy-terminal region of the rat a1 receptor-(402-410), THR-b1, raised against the unique amino-terminal portion of the b1 receptor-(62-92), and THR-b2, raised against the unique amino-terminal portion of the b2 receptor-(131-145) [34]. All antisera were kindly donated by Dr. Ronald M. Lechan, TMC-TUSM, Boston, MA. The following dilutions were used for each antiserum: Ab pro-TRH178-199 1:3000; Ab THR-a1 1:4000; Ab THR-b1 1:3000; Ab THR-b2 1:8000. Anterior pituitary sections were processed using a well-characterized antiserum recognizing the β-subunit of the rat TSH (NIDDK # 30299, kindly provided by the National Hormone and Pituitary Program-NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) diluted to 1: 500.

For ICC, all tissue sections were incubated in a solution containing the primary Ab and 0.2% Triton X-100/Tris-buffered saline-HCL (TBS), pH 7.6, for 36-48 h at 4°C. Then, the sections were washed in several changes of PBS (0.01M phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4), incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG; Vector Labs., Burlingame, CA) at a titer of 1:100 for 2 h, rinsed in two changes of PBS for 1 h and reacted with the avidin-biotin-peroxidase technique (ABC). To reduce background coloration, the sections were washed in 4 M urea (Sigma) in water for 45 min, and rehydrated in PBS for 30 min. The immunoreaction product was developed with 0.025% 3-3'-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB, Sigma) /0.045% hydrogen peroxide in TBS for 6-10 min at room temperature, to yield a brown color. The sections were counterstained with methyl green, and studied at LM using transmission and differential interference contrast, Nomarski optics.

Morphometric quantification of IR-pro-TRH178-199, IR-THRs-a1, -b1, -b2, and IR-TSH β-subunit

Quantification of IR-pro-TRH178-199, and THRs-a1, -b1, and -b2 was focused to the periventricular (pe) and medial parvocellular (mp) subdivisions of the PVN and to the external layer of the ME. pePVN and mpPVN are the source of the hypophysiotrophic TRH neurons [35] whereas the ME is the site of termination of their axon terminals [36]. Anatomical boundaries of the pePVN and mpPVN were established using as a reference the rat brain atlas of Paxinos [37] at stereotaxic coordinates Bregma -1.56 mm to -2.12 mm, whereas those of the ME were chosen at coordinates Bregma -2.56 mm to -3.30 mm. Studies were conducted on two different animals/group (control versus PCB-treated), each animal randomly selected from the original number of female rats/experimental group, using up to four different tissue sections/anatomical area of interest (either PVN or ME)/animal, each anatomical area being screened with up to 18 optical fields. The extent of the immunoreaction product was measured as Integrated Optical Density (IOD) at a fixed optical enlargement, and elaborated using computer-assisted image analysis (see section Image Analysis).

Anterior pituitary sections were examined with a Zeiss Axiophot LM equipped with 10 X 10-mm ocular grid. The number of cells/optical section, and the percentage of cells in comparable regions of the adenohypophysis were estimated using the optical dissector principle [38], based on a so-called 'systematically random sampling' (i.e., with a fixed and known periodicity of tissue section from a random starting point), and differential interference contrast, Normarski optic. Studies were conducted on two different animals/group (control versus PCB-treated), each animal randomly selected from the original number of female rats/experimental group, using four different tissue sections. Under a Plan Achromat objective at medium power (×40, N.A. 0.65), a starting optical field (so-called 'reference plane') was chosen for each section, and using the frame of the ocular grid (unbiased counting frame) the number of IR-TSH cells and nuclei of unlabeled cells coming into focus within the area of the ocular grid and the depth of 10 microns optical section (so-called 'optical dissector or look-up section') were counted with unbiased rules [38]. This procedure was repeated for the entire planar extension of the section, resulting in an equal number of measurements/section, for a total of 50 optical sections both in controls and PCB-treated rats. The percentage of IR-TSH cells was calculated by counting nuclei of labeled and unlabeld cells. Using a systematically random sampling, the estimate of the morphometric parameters in each animal was considered reliable if proportional to the systematic random sampling of a total of ~ 100 cells on an average of 10 tissue sections or 70 optical dissectors [38]. In our study, we evaluated between 192 and 575 cells on an average of 4 sections or 50 dissectors. This allowed relative quantitative conclusions, but was adequated for a comparison between controls and PCB-treated animals, as we previously showed with a lower number of counted cells and optical dissectors in the rat hypothalamus [39]. All images were captured using a Zeiss digital camera Axiocam MRc5, and Axiovision Rel 4.8 software.

Image analysis

Image analysis was performed thanks to the courtesy of Dr. Ronald M. Lechan, at the Tupper Research Institute-TMC-TUSM in Boston, MA, USA using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope under light transmission. Images were acquired using a COHU 4912 video camera, and analyzed with a Macintosh G4 computer using Scion Image software. Background ICC staining was removed by thresholding the image, and IOD values (density of staining x stained area) of IR-neurons in the pePVN/mpPVN and IR-axon terminals in the external layer of the ME were measured adding together the IODs of the different optical fields/stained area at constant optical enlargement. Values corresponding to the content of IR-pro-TRH and IR-THRs-a1, -b1, and -b2 were calculated for each section, and values of all sections used to yield a mean ± SEM IOD/anatomical area of interest.

Hormone determinations

Blood samples were collected from trunk blood after decapitation. To separate and collect the serum, blood was centrifugated at 8,000 rpm for 10 min. Serum concentrations of FT3 and FT4 were measured at PND21 and 5 weeks later using a commercial kit (MP Biomedicals, Asse-Relegem, Belgium). Assay sensitivity for FT4 and FT3 was 0.4 and 0.05 pg/ml, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Differences in serum concentrations of FT3 and FT4, IODs of IR-pro-TRH, and IR-THRs-a1, -b1, and -b2 in the ME and PVN, and linearized (by arcsin transformation) percentages and number/optical section of pituitary TSH cells between control and PCB-treated female rats were evaluated using the unpaired Student´s t-Test. Proportion of stained versus unstained pituitary TSH cells was also assessed using a chi-squared, 2x2 contingency table. All differences were considered significant if p<0.05.

Results

Respect to controls, continuous gestational (E10- E19) and postnatal (P1-P21) exposure to the PCB mixture lowered the mean levels of FT3 and FT4 of 25% and 13%, respectively in female rats. Similar, in adult females mean levels of FT3 and FT4 were reduced of 14% and 13%, respectively. Nevertheless, these changes did not reach statistical significance (Figures 1A and 1B).

Figure 1. A) Serum TH levels of post-weaned female rats, whose mothers received a mixture of PCBs 138, 153, 180, and 126 from mid-pregnancy to the end of lactation and, B) the same female rats at adult age (two months’ old). Control rats were born from dams receiving only vehicle. No statistically significant difference occurred at any age with respect to controls. Values are expressed as the mean ± SEM and refer to 10-12 animal/experimental group. NS: not statistically significant with respect to controls (Data were provided by the courtesy of Daniela Cocchi as a part of the collaborative Project MIUR PRIN04, and can also be found at Cocchi et al. [40]).

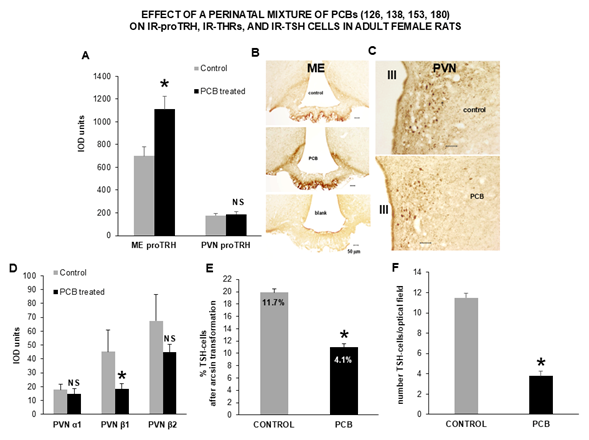

However, compared to controls, adult females showed a statistically significant increase (p=0.003802) in the mean IOD for IR-pro-TRH in axon terminals of the external layer of the ME (Figures 2A and 2B). In contrast, no change occurred to the mean IOD of IR-pro-TRH in cell bodies, dendrites and neuropil fibers of the pePVN and mpPVN (Figure 2A and 2C). A statistically significant decrease (p = 0.038527) also occurred to the mean IOD of IR-THR-b1 in cell nuclei of the pePVN and mpPVN. In contrast, no statistically significant changes occurred to the mean IOD of IR-THRs-a1 and -b2 in the cell nuclei of the same anatomical areas (Figure 2D).

Finally, with respect to controls, a statistically significant decrease (p<0.00001) in the mean percentage (Figure 2E) and number (Figure 2F) of IR-TSH cells was observed in the anterior pituitary of adult females. Differences in percentages were doubly checked through both a linearized, arcsin transformation of the original percentage values for their use as means, and a contingency table confronting the original number of stained versus unstained cells (chi-squared=186.159; p=0.0001). Remarkably, using the same number of optical fields (50 samples), no statistically significant difference emerged in the mean number of unstained cells between adult control and PCB-treated female rats (4340 vs 4477 cells, p=0.17105), suggesting a specific effect of the treatment on TSH cells.

Figure 2. A) Compared to control rats, adult females from mothers treated with the PCB mixture during pregnancy and lactation showed a statistically significant increase in the IOD of IR-proTRH in axon terminals of the ME. In contrast, no changes in IOD occurred to IR-proTRH in neuronal cell bodies and dendrites of the pePVN and mpPVN. This was readily apparent at the LM level, where B) the external layer of the ME revealed a brown staining much more intense than that of controls (blank signifies absence of primary antibody against proTRH). This contrasted with C) neuronal cell bodies and fibers in the PVN, that stained at comparable visual intensity; D) a statistically significant decrease occurred to the IOD of IR-THR-β1 in nuclei of neurons of the pePVN and mpPVN. In contrast, in the same area no changes were revealed for IR-THRs-α1 and -β2; finally, a statistically significant decrease occurred to E) the percentage of IR-TSH cells and, F) number of IR-TSH cells in the anterior pituitary. Percentages are shown as arcsin-transformed values, whereas the original cell proportions are reported inside the bars, and their statistically significant difference established with a chi-squared 2x2 contingency table. Each graphic depicts the results of independent measurements on two different, control and PCB-treated rats. Each image was selected from an index animal, and from an average of three different optical fields. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM; *: p<0.05; NS: not statistically significant with respect to controls; III: third ventricle; PVN: Paraventricular Nucleus; ME: Median Eminence.

Discussion

Recently, we showed that perinatal exposure of rats to Aroclor 1254 (A1254), a mixture of more than 90 polychlorinated biphenils (PCBs) hampered the TRH-TSH axis in their adulthood, and in a sex-specific manner [28]. In particular, no changes occurred to the gene expression of hypophysiotrophic TRH, whereas serum levels of pituitary TSH increased at a statistically significant level in females with respect to controls [28]. To elucidate which specific PCB of that mixture could have exerted such a disrupting effect at central level, in the present experiments we chose the three most prevalent, heavily chlorinated, non-dioxin-like PCB congeners found in humans and wildlife (noncoplanar 138, 153, 180), and the most potent dioxin-like, lesser chlorinated PCB (coplanar 126) administered to dams during pregnancy and lactation, in a proportion similar to that found in the environment [29,30].

With this protocol, we tried to mimic an environmental contamination by specific PCBs during prenatal and first stages of neonatal life, with the intent to unravel effects in the adult life at the level of the hypothalamic and pituitary cells regulating the thyroid axis. In humans, data of this type are lacking: recent clinical/epidemiological studies have suggested that potential long term and subliminal central effects of PCBs on the thyroid axis run largely unrecognized in offsprings [41,42], especially with non-dioxin PCB congeners and in females [43], though infants of both sexes have also been reported to display primary HYPO (pHYPO) [44] and euthyroid hyperthyroxinemia by increased thyroxin-binding globulin (TBG) in males [45]. In contrast, contradictory and inconsistent results have been reported in pregnant mothers, ranging from euthyroidism to pHYPO [42,44,46], the latter belived to contribute to neurodevelopmental disturbances observed in their kids [46]. Thus, evidence for a disruptive effect of PCBs on the cellular components of the TRH-TSH axis in an animal model might provide suggestions on still poorly appreciated alterations in the central thyrotrophic axis of children born in polluted areas. Examples of this reasoning concerns the inhibitory effects of PCBs on liver D1 synthesis in rats [20], whose genetic polymorphism in pregnant women has been suggested as an explanation for their variable levels in circulating T4 in response to PCB pollution [42] or the low levels of T4 and FT4 in pregnant rats exposed to PCBs [47] that replicate the pHYPO observed in pregnant women living in contaminated areas [44].

To improve the reliability of our results, we decided to reduce the exposure dosage of PCBs to an average of one third with respect to our previous study [28]. In fact, current data in humans suggest that exposure to low-level PCBs during pregnancy would be the most insidious modality for reproductive impairment, including long term disturbances in children [48]. Unfortunately, nothing is known about in vivo low-doses PCBs on the thyroid axis, although our group recently tackled a research program to in vitro test effects of subliminal PCBs on the rat thyroid gland [49]. Preliminary results showed that PCB 153 in a dose-range very similar to that used in the current in vivo experiments, can in vitro inhibit key transduction molecules of the acute inflammatory response network in rat thyroid cells including STAT3, Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist, and ICAM1 likely favoring disruption of immune surveillance in the thyroid gland [50]. In addition, since two of the PCBs (153 and 180) used in the present experiments were shown to accumulate in the fetal rat hypothalamus [51] when administered perinatally at a dose lower than the current one, we concluded that evidence of an even subtle effect on central components of the thyroid axis in adult female rats from contaminated dams might encourage prevention of similar central disorders in female adolescents born from mothers living in polluted areas. Indeed, gestational administration of a mixture equivalent to that we used (PCBs 138, 153, 180) but 10 times lower in dosage was shown to acutely disrupt the neuroendocrine development of the gonadal axis in rat pups [52], reasonably suggesting similar expectations in the neuroendocrine development of the thyroid axis both in rats and humans [46,47].

In our experiments, no statistically significant changes occurred to free TH levels in either pups and young adult female rats, excluding pHYPO. However, a reduction in FT3 of 25% of control values was early recorded, similar to a reduction in FT4 previously reported in female rats of the same age, perinatally treated with A1254 at a dosage similar to our PCB mixture [21]. Since in human’s fluctuations to lower limits of normality in free THs may be indicative of cHYPO [18,19], we raised the possibility that perinatal PCB treatment had induced an inadequate central adaptation of the thyroid axis in our adult female rats. Indeed, when we focused on the content of pro-TRH in the pePVN, mpPVN, and external layer of the ME, we found its statistically significant accumulation in the latter, as in the case of reduced release of hypophysiotrophic TRH. To our knowledge, this is the first experimental observation that links perinatal PCB treatment to the restraint of TRH in the ME. Consistently, glycosilation of pituitary TSH would be impaired [53], and less effective synthesis of TH hormone would occur, like in human cHYPO [19].

Support to this possibility is offered by the knowledge that PCBs may act as TH analogues [7,11,22]. By binding to THR-b2 in the end-feet processes of tanycytes in the ME, PCBs might favor tanycytic encasement of TRH axon terminals [54], thus impeding TRH to enter the portal blood. Similar, very high doses of T3 in the ME reduce access of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) axon terminals to portal capillaries, as a result of impinging tanycyte end-feets that prevent photoperiodic release of GnRH and pituitary gonadotropins [55]. A PCB action as TH-analogues on tanycytes seems further feasible by recent investigations on the role of tanycytic THR-a1 in regulating the morphology of tanycyte end-feets in the ME for the release of TRH [56]. Additionally, we cannot exclude that increased level of TH-related signaling by PCBs to ME tanycytes would trigger degradation of portal TRH through activation of the tanycyte pyroglutamyl petidase II, as observed in the course of hyperthyroidism [57].

Finally, the non-dioxin-like PCBs of our mixture might have also influenced the molecular machinery related to the histone deacetylase, anti-aging, and energy-sensing gene product SIRT1 [58,59] in hypophysiotrophic TRH neurons. Indeed, the biosynthesis of this protein is inversely regulated by circulating levels of THs in peripheral tissues of adult male mice [60], and SIRT1 favors TSH release from adult male rat and human pituitary cells in culture, whose in vivo meaning is likely to balance modifications in energy intake [61]. Since reduction of SIRT1 signaling may lead to a condition of cHYPO in adult male rats through inhibition of hypophysiotrophic TRH biosynthesis [62], it is reasonable to believe that a PCB-related, low SIRT1 levels in developing female pups might have contributed to derange hypophysiotrophic TRH neurons in our adult female rats. The exact mechanism, however, remains to be determined.

By conveying hypophysiotrophic TRH to the portal blood, the PVN-ME tuberoinfundibular system controls the pituitary TSH set-point for negative feedback regulation by THs [35,54]. Efficiency of this tuberoinfundibular control depends on regulation of tuberoinfundibular pro-TRH transcription and translation by THRs-a1, -b1, and -b2 [35,53] in hypophysiotrophic TRH neurons [34]. Therefore, we measured the content of these THRs in the pePVN and mpPVN. In adult females, perinatal PCB treatment reduced the content of THR-b1 while leaving unaltered that of THR-a1 and -b2. Since the inhibitory control of hypohysiotrophic pro-TRH biosynthesis is primarily provided by THR-b2, whereas THR-b1 contributes to a lesser extent, and THR-a1 would exerts an opposite effect [53,63-65], we concluded that loss of THR-b1 could have been “compensated” by unaltered levels of the other two THRs. This seems feasible also by the fact that PCBs of the same type of those of our mixture may interact with THRs without preventing the action of THs, i.e. in a non-competitive manner [23,24]. As a result, no changes to pro-TRH translation would occur in the PVN reached by control TH levels, a possibility consistent with our previous evidence of unchanged pro-TRH transcription in the PVN of adult female rats perinatally-treated with PCBs [28].

Support to the development of a cHYPO in our adult female rats was also offered by the observation that perinatal PCB treatment induced a reduction in the proportion and number of their pituitary thyrotrophs. Since TRH is essential to survival and growth of TSH-cells, and its deprivation reduces their number in the anterior pituitary [66] while hampering TSH glycosilation [67], we concluded that diminished release of hypophysiotrophic TRH could have been a primary cause for the observed pituitary cell loss. We can not exclude also a direct proapoptotic effect of the non dioxin-like PCBs of our mixture on thyrotrophs [68], however, this possibility seems unlikely as a result of absence of statistically significant changes in the number of all the remaining unstained pituitary cells, supporting a role for the reduced TRH as a key factor. This would also be consistent with our previous observation of increased TSH secretion in adult female rats having a similar treatment protocol [28], likely due to a compensation for the impaired TSH glycosilation. Whether this compensation would involve a reduced activity of the pituitary D2, and/or a xenoestrogenic effect of the dioxin-like PCB 126 to increase TBG and thus, to sequester circulating free THs leading to a minor negative feedback on the pituitary, remains to be determined.

In conclusion, our morphofunctional results suggest that perinatal exposure of female rats to relatively low dose of PCB congeners largely diffused in the environment induces an inadequate adaptation of their TRH-TSH axis in the adulthood, possibly leading over time to a condition compatible with cHYPO. Translating this awareness to the clinical side, it would mean favoring alertness on the development of subtle and unrecognized central derangement of the thyroid axis in adolescent females born in geographic areas polluted with these EDs, and in pregnant women bearing prosthesis with plastic biomaterials, that represent an unexpected and surreptitious reservoir of PCBs. Whether rescue of the scavenger-like, SIRT1 intracellular signaling with specific nutritional interventions [58,69,70] might represent a new therapeutic strategy to counteract the disrupting effect of subliminal PCB levels on the TRH-TSH axis of these patients is an exciting perspective that awaits further studies.

Financial Support

This study was supported by funds of Conacyt 107109 (to ESJ), the Research Fund from INPRFM to ESJ (México), MUR PRIN 2002 P20224TAETP, MUR PRIN-PNNR 2023 P2022H74YP, FIL UNIPR 2023, Giovani Ricercatori UNIPR 2023 (Italy), and EU Horizon SCREENED 2020-2024 #825749 to RT and FB (Italy). Part of these data were preliminarly presented at the 97th Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society, San Diego, CA., March 5-8, 2015.

Author Contributions

E. Sánchez-Jaramillo and R. Toni were involved in conceptualizing the study, designing the experiments, and writing-editing the manuscript; F. Barbaro. G. Di Conza, F. Quartulli, and Y. Gzara performed the experiments and statistical analyses, S. Sprio and A. Tampieri provided key insights in medical applications of the results, including the role of biomaterials as sources of EDs contamination. All authors participated in the discussion and approval of the manuscript.

Disclosure Summary

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

2. Loganathan BG, Ahuja S, Subedi B. Synthetic Organic Chemical Pollutants in Water: Origin, Distribution, and Implications for Human Exposure and Health. In: Loganathan BG, Ahuja S, Eds. Contaminants in our water: identification and remediation methods. United States: American Chemical Society; 2020. p. 13-39.

3. Carlson LM, Christensen K, Sagiv SK, Rajan P, Klocke CR, Lein PJ, et al. A systematic evidence map for the evaluation of noncancer health effects and exposures to polychlorinated biphenyl mixtures. Environ Res. 2023 Mar 1;220:115148.

4. Costa LG, Aschner M, Kodavanti PR. Neurotoxicity of Halogenated Organic Compounds. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2023.

5. Carpenter DO. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs): routes of exposure and effects on human health. Rev Environ Health. 2006 Jan-Mar;21(1):1-24.

6. Jensen AA. Chemical contaminants in human milk. Residue Rev. 1983;89:1-128.

7. Gore AC, Zoeller RT, Currás-Collazo M. Neuroendocrine effects of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). Advances in Neurotoxicology. 2023;10:81-135.

8. Pascall MA, Zabik ME, Zabik MJ, Hernandez RJ. Uptake of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) from an aqueous medium by polyethylene, polyvinyl chloride, and polystyrene films. J Agric Food Chem. 2005 Jan 12;53(1):164-9.

9. Zhou T, Wu J, Hu X, Cao Z, Yang B, Li Y, et al. Microplastics released from disposable medical devices and their toxic responses in Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ Res. 2023 Dec 15;239(Pt 1):117345.

10. Waye A, Trudeau VL. Neuroendocrine disruption: more than hormones are upset. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2011;14(5-7):270-91.

11. McKinney JD, Waller CL. Polychlorinated biphenyls as hormonally active structural analogues. Environ Health Perspect. 1994 Mar;102(3):290-7.

12. Kodavanti PR, Curras-Collazo MC. Neuroendocrine actions of organohalogens: thyroid hormones, arginine vasopressin, and neuroplasticity. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2010 Oct;31(4):479-96.

13. Liu C, Wang C, Yan M, Quan C, Zhou J, Yang K. PCB153 disrupts thyroid hormone homeostasis by affecting its biosynthesis, biotransformation, feedback regulation, and metabolism. Horm Metab Res. 2012 Sep;44(9):662-9.

14. Collins WT, Capen CC. Ultrastructural and functional alterations of the rat thyroid gland produced by polychlorinated biphenyls compared with iodide excess and deficiency, and thyrotropin and thyroxine administration. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1980;33(3):213-31.

15. Seo BW, Li MH, Hansen LG, Moore RW, Peterson RE, Schantz SL. Effects of gestational and lactational exposure to coplanar polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) congeners or 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) on thyroid hormone concentrations in weanling rats. Toxicol Lett. 1995 Aug;78(3):253-62.

16. Liu J, Liu Y, Barter RA, Klaassen CD. Alteration of thyroid homeostasis by UDP-glucuronosyltransferase inducers in rats: a dose-response study. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995 May;273(2):977-85.

17. Chopra IJ. Clinical review 86: Euthyroid sick syndrome: is it a misnomer? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997 Feb;82(2):329-34.

18. Alexopoulou O, Beguin C, De Nayer P, Maiter D. Clinical and hormonal characteristics of central hypothyroidism at diagnosis and during follow-up in adult patients. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004 Jan;150(1):1-8.

19. Beck-Peccoz P, Rodari G, Giavoli C, Lania A. Central hypothyroidism - a neglected thyroid disorder. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017 Oct;13(10):588-98.

20. Giera S, Bansal R, Ortiz-Toro TM, Taub DG, Zoeller RT. Individual polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) congeners produce tissue- and gene-specific effects on thyroid hormone signaling during development. Endocrinology. 2011 Jul;152(7):2909-19.

21. Morse DC, Wehler EK, Wesseling W, Koeman JH, Brouwer A. Alterations in rat brain thyroid hormone status following pre- and postnatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls (Aroclor 1254). Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1996 Feb;136(2):269-79.

22. You SH, Gauger KJ, Bansal R, Zoeller RT. 4-Hydroxy-PCB106 acts as a direct thyroid hormone receptor agonist in rat GH3 cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006 Sep 26;257-258:26-34.

23. Bogazzi F, Raggi F, Ultimieri F, Russo D, Campomori A, McKinney JD, et al. Effects of a mixture of polychlorinated biphenyls (Aroclor 1254) on the transcriptional activity of thyroid hormone receptor. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003 Oct;26(10):972-8.

24. Gauger KJ, Kato Y, Haraguchi K, Lehmler HJ, Robertson LW, Bansal R, et al. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) exert thyroid hormone-like effects in the fetal rat brain but do not bind to thyroid hormone receptors. Environ Health Perspect. 2004 Apr;112(5):516-23.

25. Cheek AO, Kow K, Chen J, McLachlan JA. Potential mechanisms of thyroid disruption in humans: interaction of organochlorine compounds with thyroid receptor, transthyretin, and thyroid-binding globulin. Environ Health Perspect. 1999 Apr;107(4):273-8.

26. Liu C, Ha M, Li L, Yang K. PCB153 and p,p'-DDE disorder thyroid hormones via thyroglobulin, deiodinase 2, transthyretin, hepatic enzymes and receptors. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2014 Oct;21(19):11361-9.

27. Duntas LH. Chemical contamination and the thyroid. Endocrine. 2015 Feb;48(1):53-64.

28. Sánchez-Jaramillo E, Sánchez-Islas E, Gómez-González GB, Yáñez-Recendis N, Mucio-Ramírez S, Barbaro F, et al. Perinatal exposure to Aroclor 1254 disrupts thyrotropin-releasing hormone mRNA expression in the paraventricular nucleus of male and female rats. Toxicology. 2024 Nov;508:153935.

29. Gladen BC, Doucet J, Hansen LG. Assessing human polychlorinated biphenyl contamination for epidemiologic studies: lessons from patterns of congener concentrations in Canadians in 1992. Environ Health Perspect. 2003 Apr;111(4):437-43.

30. Kodavanti PR. Neurotoxicity of persistent organic pollutants: possible mode (s) of action and further considerations. Dose-Response. 2006 May 1;3(3):273-305

31. Colciago A, Casati L, Mornati O, Vergoni AV, Santagostino A, Celotti F, et al. Chronic treatment with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB) during pregnancy and lactation in the rat Part 2: Effects on reproductive parameters, on sex behavior, on memory retention and on hypothalamic expression of aromatase and 5alpha-reductases in the offspring. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009 Aug 15;239(1):46-54.

32. Toni R, Jackson IMD, Lechan RM. Neuropeptide Y-immunoreactive innervation of thyrotropin-releasing hormone- synthesizing neurons in the rat hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Endocrinolgy. 1990;26:2444-53.

33. Nillni EA, Aird F, Seidah NG, Todd RB, Koenig JI. PreproTRH(178-199) and two novel peptides (pFQ7 and pSE14) derived from its processing, which are produced in the paraventricular nucleus of the rat hypothalamus, are regulated during suckling. Endocrinology. 2001 Feb;142(2):896-906.

34. Lechan RM, Qi Y, Jackson IM, Mahdavi V. Identification of thyroid hormone receptor isoforms in thyrotropin-releasing hormone neurons of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Endocrinology. 1994 Jul;135(1):92-100.

35. Lechan RM, Fekete C, Toni R. Thyroid Hormone in Neural Tissue. In: Pfaff DW, Arnold AP, Etgen AM, Fahrbach SE, Rubin RT, Eds. Hormones, brain, and behavior. Netherlands: Academic Press; 2009. p.1289-330.

36. Lechan RM, Nestler JL, Jacobson S. The tuberoinfundibular system of the rat as demonstrated by immunohistochemical localization of retrogradely transported wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) from the median eminence. Brain Res. 1982 Aug 5;245(1):1-15.

37. Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Netherlands: Elsevier Academic Press; 2005.

38. West MJ, Gundersen HJ. Unbiased stereological estimation of the number of neurons in the human hippocampus. J Comp Neurol. 1990 Jun 1;296(1):1-22.

39. Toni R, Mosca S, Ruggeri F, Valmori A, Orlandi G, Toni G, et al. Effect of hypothyroidism on vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-immunoreactive neurons in forebrain-neurohypophysial nuclei of the rat brain. Brain Res. 1995 Jun 5;682(1-2):101-15.

40. Cocchi D, Tulipano G, Colciago A, Sibilia V, Pagani F, Viganò D, et al. Chronic treatment with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB) during pregnancy and lactation in the rat: Part 1: Effects on somatic growth, growth hormone-axis activity and bone mass in the offspring. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009 Jun 1;237(2):127-36.

41. Matsuura N, Uchiyama T, Tada H, Nakamura Y, Kondo N, Morita M, et al. Effects of dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) on thyroid function in infants born in Japan--the second report from research on environmental health. Chemosphere. 2001 Dec;45(8):1167-71.

42. Berlin M, Barchel D, Brik A, Kohn E, Livne A, Keidar R, et al. Maternal and newborn thyroid hormone, and the association with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) burden: the EHF (Environmental Health Fund) birth cohort. Front Pediatr. 2021 Sep 13;9:705395.

43. Baba T, Ito S, Yuasa M, Yoshioka E, Miyashita C, Araki A, et al. Association of prenatal exposure to PCDD/Fs and PCBs with maternal and infant thyroid hormones: the Hokkaido study on environment and children’s health. Sci Total Environ. 2018 Feb 15;615:1239-46.

44. Koopman-Esseboom C, Morse DC, Weisglas-Kuperus N, Lutkeschipholt IJ, Van der Paauw CG, Tuinstra LG, et al. Effects of dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls on thyroid hormone status of pregnant women and their infants. Pediatr Res. 1994 Oct;36(4):468-73.

45. Su PH, Chen HY, Chen SJ, Chen JY, Liou SH, Wang SL. Thyroid and growth hormone concentrations in 8-year-old children exposed in utero to dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls. J Toxicol Sci. 2015 Jun;40(3):309-19.

46. Chevrier J, Eskenazi B, Holland N, Bradman A, Barr DB. Effects of exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and organochlorine pesticides on thyroid function during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 2008 Aug 1;168(3):298-310.

47. Naveau E, Pinson A, Gérard A, Nguyen L, Charlier C, Thomé JP, et al. Alteration of rat fetal cerebral cortex development after prenatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls. PLoS One. 2014 Mar 18;9(3):e91903.

48. Di Renzo GC, Conry JA, Blake J, DeFrancesco MS, DeNicola N, Martin JN Jr, et al. International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics opinion on reproductive health impacts of exposure to toxic environmental chemicals. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015 Dec;131(3):219-25.

49. Moroni L, Barbaro F, Caiment F, Coleman O, Costagliola S, Conza GD, et al. SCREENED: A multistage model of thyroid gland function for screening endocrine-disrupting chemicals in a biologically sex-specific manner. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 May 21;21(10):3648.

50. Quartulli F, Di Conza G, Barbaro F, Sprio S, Tampieri A, Toni R. A bioinformatic interactomic analysis of “high-dimensional data” from proteome functional clusters: innovations from the Horizon Project SCREENED #825745 based on rat thyroid stem cells tested in an EU Joint Research Centre-submitted in vitro assay. Abstracts Research Day DIMEC - UNIPR, October 4, 2024. Available from: https://www.unipr.it/sites/default/files/2024-10/AGENDA_Research%20Day_2024_finalissimo.pdf

51. Pravettoni A, Colciago A, Negri-Cesi P, Villa S, Celotti F. Ontogenetic development, sexual differentiation, and effects of Aroclor 1254 exposure on expression of the arylhydrocarbon receptor and of the arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator in the rat hypothalamus. Reprod Toxicol. 2005 Nov-Dec;20(4):521-30.

52. Dickerson SM, Cunningham SL, Gore AC. Prenatal PCBs disrupt early neuroendocrine development of the rat hypothalamus. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011 Apr 1;252(1):36-46.

53. Persani L. Hypothalamic thyrotropin-releasing hormone and thyrotropin biological activity. Thyroid. 1998 Oct;8(10):941-6.

54. Fekete C, Lechan RM. Central regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis under physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Endocr Rev. 2014 Apr;35(2):159-94.

55. Yamamura T, Yasuo S, Hirunagi K, Ebihara S, Yoshimura T. T3 implantation mimics photoperiodically reduced encasement of nerve terminals by glial processes in the median eminence of Japanese quail. Cell Tissue Res. 2006 Apr;324(1):175-9.

56. Chandrasekar A, Abele S, Fahnrich A, Spiecker F, Mittag J, Schwaninger M, et al. Tanycytic thyroid hormone signalling in the regulation of hypothalamic functions and hormone uptake. In Endocrine Abstracts 2023 Aug 24 (Vol. 92). Bioscientifica.

57. Sánchez E, Vargas MA, Singru PS, Pascual I, Romero F, Fekete C, et al. Tanycyte pyroglutamyl peptidase II contributes to regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis through glial-axonal associations in the median eminence. Endocrinology. 2009 May;150(5):2283-91.

58. Guida N, Laudati G, Anzilotti S, Secondo A, Montuori P, Di Renzo G, et al. Resveratrol via sirtuin-1 downregulates RE1-silencing transcription factor (REST) expression preventing PCB-95-induced neuronal cell death. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015 Nov 1;288(3):387-98.

59. Quitete FT, Teixeira AVS, Peixoto TC, Martins BC, Atella GC, Resende AC, et al. Long-term exposure to polychlorinated biphenyl 126 induces liver fibrosis and upregulates miR-155 and miR-34a in C57BL/6 mice. PLoS One. 2024 Aug 12;19(8):e0308334.

60. Cordeiro A, de Souza LL, Oliveira LS, Faustino LC, Santiago LA, Bloise FF, et al. Thyroid hormone regulation of Sirtuin 1 expression and implications to integrated responses in fasted mice. J Endocrinol. 2013 Jan 18;216(2):181-93.

61. Akieda-Asai S, Zaima N, Ikegami K, Kahyo T, Yao I, Hatanaka T, et al. SIRT1 regulates thyroid-stimulating hormone release by enhancing PIP5Kgamma activity through deacetylation of specific lysine residues in mammals. PLoS One. 2010 Jul 23;5(7):e11755.

62. Hasegawa K, Kawahara T, Fujiwara K, Shimpuku M, Sasaki T, Kitamura T, et al. Necdin controls Foxo1 acetylation in hypothalamic arcuate neurons to modulate the thyroid axis. J Neurosci. 2012 Apr 18;32(16):5562-72.

63. Abel ED, Ahima RS, Boers ME, Elmquist JK, Wondisford FE. Critical role for thyroid hormone receptor beta2 in the regulation of paraventricular thyrotropin-releasing hormone neurons. J Clin Invest. 2001 Apr;107(8):1017-23.

64. Abel ED, Moura EG, Ahima RS, Campos-Barros A, Pazos-Moura CC, Boers ME, et al. Dominant inhibition of thyroid hormone action selectively in the pituitary of thyroid hormone receptor-beta null mice abolishes the regulation of thyrotropin by thyroid hormone. Mol Endocrinol. 2003 Sep;17(9):1767-76.

65. Dupré SM, Guissouma H, Flamant F, Seugnet I, Scanlan TS, Baxter JD, et al. Both thyroid hormone receptor (TR)beta 1 and TR beta 2 isoforms contribute to the regulation of hypothalamic thyrotropin-releasing hormone. Endocrinology. 2004 May;145(5):2337-45.

66. Nikrodhanond AA, Ortiga-Carvalho TM, Shibusawa N, Hashimoto K, Liao XH, Refetoff S, et al. Dominant role of thyrotropin-releasing hormone in the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis. J Biol Chem. 2006 Feb 24;281(8):5000-7.

67. Taylor T, Weintraub BD. Thyrotropin (TSH)-releasing hormone regulation of TSH subunit biosynthesis and glycosylation in normal and hypothyroid rat pituitaries. Endocrinology. 1985 May;116(5):1968-76.

68. Raggi F, Russo D, Urbani C, Sardella C, Manetti L, Cappellani D, et al. Divergent effects of dioxin- or non-dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyls on the apoptosis of primary cell culture from the mouse pituitary gland. PLoS One. 2016 Jan 11;11(1):e0146729.

69. Martins IJ. Anti-aging genes improve appetite regulation and reverse cell senescence and apoptosis in global populations. Advances In Aging Research. 2016;05(01):9-26.

70. Martins IJ. Increased risk for obesity and diabetes with neurodegeneration in developing countries. In: Top 10 contributions on Genetics. Avid Science; 2018. p. 1-35.