Abstract

Aim: Early identification of mortality risk remains a challenge in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). The Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI), a simple tool reflecting combined nutritional and immunological status (via serum albumin and lymphocyte count), has shown promise across various critically ill populations. This study aims to evaluate the prognostic value of PNI in predicting in-hospital mortality among a cohort of adult patients admitted to a medical ICU, and to assess its clinical utility as an accessible biomarker for risk stratification.

Method: This single-center, retrospective cohort study included 266 patients aged ≥18 years who were admitted to the ICU between November 1, 2023, and November 1, 2024. Data collected included patients' demographic features (age, gender), comorbid conditions (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension, malignancy), clinical outcomes (survival status, ICU length of stay), and laboratory variables, particularly serum albumin concentration and total lymphocyte count, which are essential components of the PNI. PNI = [10 × serum albumin (g/dL)] + [0.005 × total lymphocyte count (cells/mm³)]. Statistical analyses included univariate and multivariate logistic regression models and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

Results: Of the 266 patients included in this study, 117 (44.1%) died during their ICU stay. Non-survivors had significantly lower PNI scores compared to survivors (p=0.001). ROC curve analysis identified an optimal PNI cut-off value of ≤32, with a sensitivity of 43.2%, specificity of 90.3%, and an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.719—indicating moderate discriminative ability. Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that prolonged ICU stay (OR 1.070, 95% CI [1.015–1.125]), hypoalbuminemia (OR 2.670, 95% CI [1.226–3.987]), high serum urea (OR 1.014, 95% CI [1.001–1.027]), and increased lactate levels (OR 1.234, 95% CI [1.012–1.456]) were independent predictors of mortality (all p<0.05).

Conclusion: Given that PNI is derived from routine, readily available laboratory parameters, it stands out as a valuable adjunct to established prognostic models, particularly in resource-limited settings. While its discriminatory power may be limited when used in isolation, PNI contributes meaningfully to multidimensional risk assessments due to its ability to reflect both nutritional and immunological status. In this study, lower PNI values were significantly associated with in-hospital mortality among ICU patients, supporting its role as a clinically relevant marker. Beyond its quantitative value, PNI can facilitate individualized treatment planning, may support individualized monitoring strategies, and enrich multidisciplinary decision-making frameworks. Therefore, it should be regarded not merely as a numerical score, but as a practical and adaptable tool in the complex landscape of intensive care prognostication.

Keywords

Prognostic Nutritional Index, Nutritional status, Intensive Care Unit, Mortality

Introduction

Intensive care units (ICUs) represent one of the most critical environments in modern medicine, where early identification of patients at high risk of mortality is essential for improving outcomes. Malnutrition is a common yet often underestimated prognostic factor associated with increased infection rates, prolonged hospitalization, impaired wound healing, and higher mortality—particularly among elderly or chronically ill individuals [1,2]. Evidence further suggests that improving the nutritional status of critically ill patients may enhance recovery and reduce nosocomial infection risk [3]. The Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI), derived from serum albumin concentration and total lymphocyte count, provides an objective measure of combined nutritional and immunological status. Initially developed for oncologic populations, PNI has gained increasing relevance in critical care due to its association with systemic inflammation, immune competence, and physiological reserve [4]. Previous studies have demonstrated that lymphocytopenia (<800 cells/μL) and hypoalbuminemia (<3.0 g/dL) are independently linked to increased morbidity and mortality across a wide range of medical conditions, including renal failure, heart failure, and malignancies [5,6]. Furthermore, meta-analytical data indicate that patients with low PNI scores (<45) exhibit a 2.3-fold greater risk of postoperative mortality, a 5.2-day longer hospital stay, and a 67% increase in nosocomial infections [5]. These findings highlight the importance of nutritional–immunological indicators in risk assessment and prognostic evaluation. Given this evidence, PNI has emerged as a simple, reproducible, and accessible biomarker with potential value for early risk stratification in critically ill patients. The present study aims to evaluate the prognostic significance of PNI measured at ICU admission in predicting in-hospital mortality among adult medical ICU patients.

Method

Study design

This is a retrospective study on patients in the internal medicine ICU between 01.11.2023 and 01.11.2024, the medical records of the patients were examined and obtained through the hospital information management system. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital (Protocol number:2025-01/05). Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data were retrospectively retrieved from the hospital’s electronic health records. Variables included age, gender, comorbidities, length of ICU stay, and laboratory parameters such as serum albumin and lymphocyte count. Demographic data included age, gender status, while clinical data consisted of information about the patients' personal history, treatment duration and current health status. In addition, laboratory test results (hemogram, biochemical analyses, albumin and lymphocyte levels, which are essential for PNI calculation) were collected retrospectively. All data were anonymized and personal information was protected. Within the first 24 hours of ICU admission, serum albumin (g/dL) and total lymphocyte count (/mm³) were obtained to calculate the PNI. Additional laboratory parameters (C-reactive protein (CRP), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), lactate, creatinine, etc.) were recorded for comparative analyses. The PNI was calculated for each patient using the formula PNI= (10 x albumin [g/dL]) + (0.005 x lymphocyte count [per mm3]). Exclusion criteria were being under 18 years of age, being pregnant and lack of data. Two hundred sixty-six patients participated in the study.

Statistical analysis

MedCalc version 14.0 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium) and SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) were used for all statistical analyses. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to evaluate the distribution of continuous variables, and Levene's test was used to evaluate the homogeneity of variances. When comparing two independent groups, normally distributed variables were compared using the Independent Samples t-test with bootstrapping, and non-normally distributed variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test with Monte Carlo simulation. The discriminatory power of the PNI was evaluated using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, which included sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) computations. The Youden index was used to determine the cut-off values. Additionally, univariate logistic regression was used to identify potential predictors of mortality, and variables with p<0.1 were added to a multivariate logistic regression model to identify independent risk factors. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

Results

A total of 266 patients (age range: 18–94 years) were included in the study, and the following results were obtained: of the 266 patients 129 were male and 137 were female. Comparative analyses showed that there was no statistically significant difference between groups based on gender (p>0.05). One hundred forty-nine patients (56%) were discharged from the ICU, while 117 patients (44%) died during their stay in the ICU (exitus). Comparative analysis showed no statistically significant difference between groups by gender (p>0.05). Significant differences in; age distribution (p<0.05), duration of ICU stay (p<0.05).

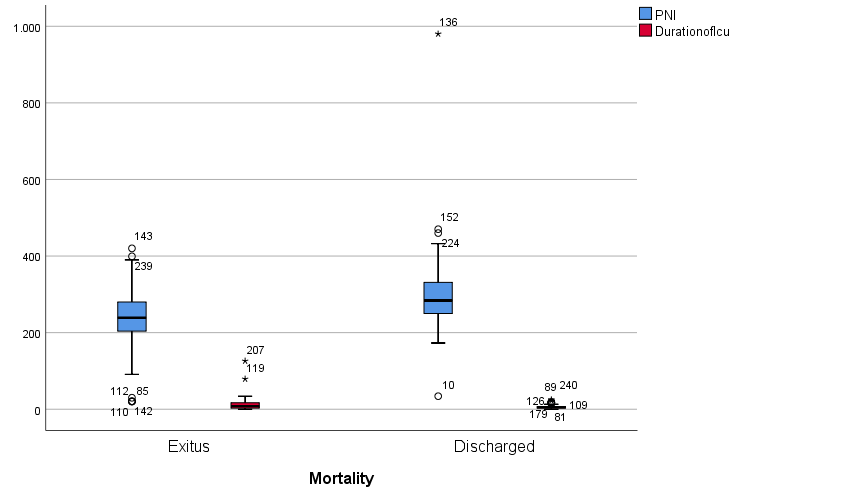

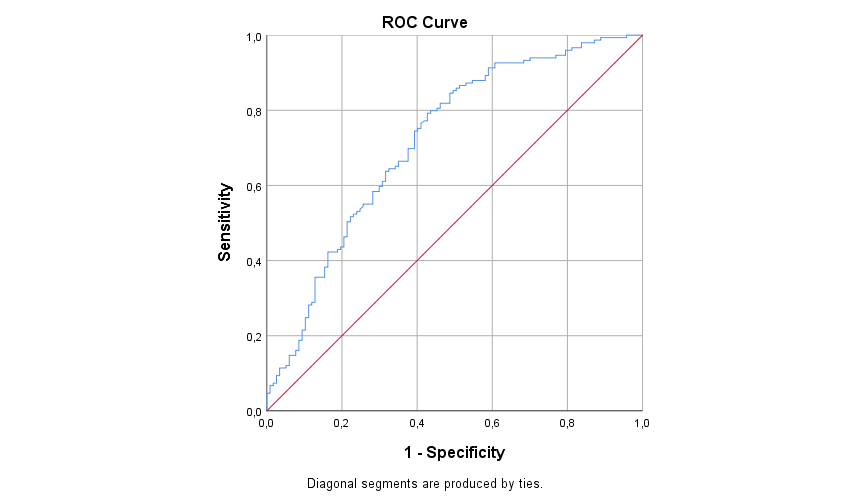

Values for erythrocyte distribution width (RDW), CRP, BUN, creatinine, lactate, and phosphorus were significantly greater in the death group than in the discharged patients (p<0.05). Significantly lower levels of hemoglobin, platelet count, hematocrit, albumin, calcium, and PNI were seen in the mortality group (p<0.05) (Table 2). PNI scores were significantly lower, while ICU length of stay was significantly longer in non-survivors compared with survivors (p=0.001) (Figure 1). ROC analysis demonstrated that PNI exhibited a moderate discriminative capacity for mortality prediction, with an AUC of 0.719 (p<0.001). The optimal PNI cutoff value for mortality prediction was <32, yielding a sensitivity of 43.1% and a specificity of 90.1% (Figure 2).

In the regression model (Nagelkerke R²=0.351, accuracy=74.8%), significant predictors of mortality included intensive care length of stay (OR=1.070), low albumin levels (OR=2.607), elevated urea (OR=1.014), and high lactate levels (OR=1.234) (all p<0.05) (Table 3).

|

|

Mortality |

N |

Row mean |

Row Total |

u |

z |

p |

|

Gender |

Discharged |

149 |

132,88 |

19798,50 |

8623,500 |

-,173 |

,863 |

|

|

Exitus |

117 |

134,29 |

15712,50 |

|

|

|

|

Age |

Discharged |

149 |

142,27 |

21198,00 |

7410,000 |

-2,098 |

,036* |

|

|

Exitus |

117 |

122,33 |

14313,00 |

|

|

|

|

Duration of ICU stay |

Discharged |

149 |

112,09 |

16141,00 |

5701,00 |

-4,503 |

,000* |

|

|

Exitus |

117 |

154,27 |

18050,00 |

|

|

|

|

ICU: Intensive Care Unit |

|||||||

|

|

Mortality |

N |

Row mean |

Row Total |

u |

z |

P |

|

Hemoglobin (HGB) (g/dl) |

Discharged |

149 |

144,45 |

21522,50 |

7085,500 |

-2,619 |

,009* |

|

|

Exitus |

117 |

119,56 |

13988,50 |

|

|

|

|

Neutrophils (NEU) (10³/mm³) |

Discharged |

149 |

125,83 |

748,00 |

7573,00 |

-1,617 |

,106 |

|

|

Exitus |

115 |

141,15 |

16232,00 |

|

|

|

|

Lymphocyte |

Discharged |

148 |

132,14 |

19557,00 |

8489,00 |

-,034 |

,973 |

|

|

Exitus |

115 |

131,82 |

15159,00 |

|

|

|

|

Platelet (PLT) |

Discharged |

149 |

141,86 |

21137,50 |

7450,500 |

-2,001 |

,045* |

|

|

Exitus |

117 |

122,85 |

14373,50 |

|

|

|

|

Hematocrit (HCT) |

Discharged |

149 |

142,45 |

21224,50 |

7383,500 |

-2,140 |

,032* |

|

|

Exitus |

117 |

122,11 |

14286,50 |

|

|

|

|

Erythrocyte (RDW) |

Discharged |

149 |

116,19 |

17312,50 |

6137,50 |

-4,142 |

,000* |

|

|

Exitus |

117 |

155,54 |

18198,50 |

|

|

|

|

Mean Platelet Volume (MPV) |

Discharged |

149 |

136,84 |

20389,00 |

8219,00 |

-,799 |

,424 |

|

|

Exitus |

117 |

129,25 |

15122,00 |

|

|

|

|

CRP (mg/L) |

Discharged |

149 |

119,90 |

17865,50 |

6690,500 |

-3,253 |

,001* |

|

|

Exitus |

117 |

150,82 |

17645,50 |

|

|

|

|

Albumin |

Discharged |

149 |

159,12 |

23709,50 |

4898,500 |

-6,131 |

,000* |

|

|

Exitus |

117 |

100,87 |

11801,50 |

|

|

|

|

Calcium (mg/dl) |

Discharged |

148 |

142,0 |

21015,50 |

7326,50 |

-2,149 |

,032* |

|

|

Exitus |

117 |

121,62 |

14229,50 |

|

|

|

|

Sodium(mmol/L) |

Discharged |

149 |

132,13 |

19687,00 |

8512,00 |

-,329 |

,742 |

|

|

Exitus |

117 |

135,25 |

15824,00 |

|

|

|

|

Magnesium (mg/dl) |

Discharged |

149 |

126,69 |

18877,50 |

7702,50 |

-1,629 |

,103 |

|

|

Exitus |

117 |

142,17 |

16633,50 |

|

|

|

|

Potassium (mmol/L) |

Discharged |

149 |

125,44 |

18690,50 |

7515,500 |

-1,930 |

,054 |

|

|

Exitus |

117 |

143,76 |

16820,50 |

|

|

|

|

Urea (mg/dl) |

Discharged |

149 |

111,63 |

16632,50 |

5457,500 |

-5,233 |

,000* |

|

|

Exitus |

117 |

161,35 |

18878,50 |

|

|

|

|

Creatinine (mg/dl) |

Discharged |

149 |

122,87 |

18308,00 |

7133,00 |

-2,543 |

,011* |

|

|

Exitus |

117 |

147,03 |

17203,00 |

|

|

|

|

Lactate (mmol/L) |

Discharged |

149 |

105,88 |

15776,50 |

4601,50 |

-6,528 |

,000* |

|

|

Exitus |

116 |

167,83 |

19468,50 |

|

|

|

|

Phosphorus (mmol/L) |

Discharged |

149 |

122,19 |

18207,00 |

7032,00 |

-2,705 |

,007* |

|

|

Exitus |

117 |

147,90 |

17304,00 |

|

|

|

|

Lipase |

Discharged |

146 |

134,28 |

19635,50 |

7623,50 |

-1,740 |

,082 |

|

|

Exitus |

113 |

124,46 |

14064,50 |

|

|

|

|

Amylase |

Discharged |

147 |

132,07 |

19415,00 |

8221,00 |

-,261 |

,794 |

|

|

Exitus |

114 |

129,61 |

14776,00 |

|

|

|

|

PNI |

Discharged |

149 |

159,13 |

23711,00 |

4897,00 |

-6,133 |

,000* |

|

|

Exitus |

117 |

100,85 |

11800,00 |

|

|

|

|

CRP: C-reactive Protein; PNI: Prognostic Nutritional Index |

|||||||

Figure 1. Box plot of PNI and duration of ICU according to mortality status. ICU: Intensive Care Unit; PNI: Prognostic Nutritional Index.

Figure 2. ROC curve of PNI for predicting in-hospital mortality. ROC: Receiver Operating Characteristic; PNI: Prognostic Nutritional Index.

|

|

95% CI |

|||

|

|

OR |

Lower |

Upper |

p |

|

Duration of ICU |

1,070 |

1,015 |

1,125 |

0,002* |

|

Albumin |

2,670 |

1,226 |

3,987 |

0,001* |

|

Urea |

1,014 |

1,001 |

1,027 |

0,020* |

|

Lactate |

1,234 |

1,012 |

1,456 |

0,038* |

|

CI: Confidence Interval; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; OR: Odds Ratio |

||||

Discussion

Early identification of mortality risk remains a central priority in critical care practice. In this study, we evaluated the prognostic value of PNI measured within the first 24 hours of ICU admission. Our findings demonstrated that lower PNI values were significantly associated with in-hospital mortality, supporting its potential role as a simple and readily obtainable marker of early physiological deterioration in critically ill patients. Previous studies have reported PNI as a prognostic factor for malignancies, infections, and cardiovascular diseases, with deceased patients consistently exhibiting significantly lower PNI scores [9,10]. Serum albumin, as the initial component of the PNI, fulfills several roles in critically ill patients. Besides sustaining intravascular oncotic pressure and fluid equilibrium, albumin modulates the transport of hormones, pharmaceuticals, and electrolytes through cellular membranes. This serves as a sensitive indicator of overall health, attributed to its immunomodulatory, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties. Hypoalbuminemia in critical care settings is frequently linked to malnutrition, systemic inflammation, heightened vascular permeability, and poorer clinical outcomes. Consequently, serum albumin functions as a nutritional biomarker and a dynamic indicator of disease severity and prognosis. The lymphocyte count, the second component in the PNI formula, is essential for host immunological response. Lymphocyte counts are also negatively correlated with disease severity in critically ill patients [10]. The pathophysiological basis of lymphopenia in critically ill patients may be due to the migration of lymphocytes from peripheral circulation to areas of infection and inflammation. Consequently, reduced lymphocyte counts indicate immunosuppression and act as a prognostic indicator of heightened mortality risk in critically ill patients [10-12]. Although lymphocyte count did not remain significant in the multivariate model, this does not diminish the clinical relevance of PNI. Albumin and lymphocyte count are biologically interrelated and may exhibit collinearity in multivariable analyses. Albumin, reflecting systemic inflammation, capillary leakage, and nutritional reserve, may exert a stronger independent effect on mortality, causing lymphocyte count to lose significance when both are included simultaneously. PNI, however, integrates both parameters into a single composite index and therefore captures broader nutritional–immunological dysfunction than albumin alone. This integration may explain its better discriminatory performance in ROC analysis despite albumin being the stronger independent predictor. A cut-off value of 30-35 was established, suggesting that PNI may serve as a valuable prognostic biomarker for critically ill patients [7]. According to a review of the literature, mortality rates in various nations range from 31.4% to 44.4% [10,11]. Mortality rates in Turkey's intensive care units (ICUs) range from 20.5% to 60.4%, according to studies (9,12-14). Disparities in patient age groups and clinical diagnoses could be the cause of these discrepancies [15]. A complex population, elderly ICU patients are frequently admitted for acute flare-ups of multiorgan dysfunction or underlying chronic conditions. Elderly ICU patients represent a complex population, often hospitalized due to underlying chronic conditions or acute exacerbations of multiorgan dysfunction. Consequently, advanced age has been identified as a significant risk factor for mortality [12]. This study further supports the finding that age is the most critical factor influencing mortality. Age is not only easily measurable and comparable but also an unmodifiable risk factor. Prior to ICU admission, parameters such as general health history, inflammatory and immune status, and physiological reserve are essential for assessing mortality risk [12,16]. A review of the literature showed consistent outcomes for different patients, Keskin et al. [7] demonstrated that PNI served as an independent predictor of mortality in coronary artery bypass surgery patients. Similarly, Hayashi et al. [6] reported that higher PNI scores correlated with shorter mechanical ventilation durations, reduced infection rates, and decreased ICU length of stay. In oncology research, Ofluo?lu et al. [8] identified PNI as a valuable biomarker for predicting surgical complications in locally advanced rectal cancer cases. These collective findings suggest that preoperative nutritional optimization may enhance treatment outcomes. Our research indicates a significant correlation between PNI values and mortality, reflecting underlying immunosuppression and malnutrition. This relationship has been shown as a strong indicator of systemic inflammation, nutritional deficiencies, and hypoalbuminemia [10,11]. Reduced lymphocyte counts likely contribute to immune dysfunction, leading to compromised inflammatory responses [9]. Consistent with these findings, regression analysis revealed that hypoalbuminemia increased mortality risk by 2.60-fold. Arslan et al. found lower PNI levels in those who did not survive, but these were not identified as an independent predictor. The findings highlighted the relationship between PNI, nutritional status, and immune function, particularly in elderly patients, and it was observed that PNI scores were significantly lower in deceased cases. This supports the role of PNI as a strong nutritional indicator for elderly intensive care patients [12]. Similarly, Taskin et al. reported that preoperative PNI scores were significantly lower in patients with non-surviving femur fractures (six-month mortality rate 22.4%) and set 29 as a threshold value [13]. There were 1,115 cases included in a more extensive study, Ushirozako et al. identified low preoperative PNI values as a risk factor for surgical site infections after spinal surgery [14]. Hu et al. verified that low PNI is a significant risk factor for postoperative infections, indicating that PNI more effectively predicted than CRP levels after gastrointestinal fistula surgery [15]. Therefore, we think it is essential to further elucidate the correlation between the PNI as a supportive, non-invasive biomarker for prediction mortality in ICU patients. By integrating PNI assessments into routine clinical practice, healthcare providers may enhance their ability to identify high-risk patients and implement timely interventions. Furthermore, the relationship between changes in PNI’s components during therapeutic effects could be investigated in future enhanced treatment strategies.

Limitations and Future Directions

The limitations of the current study must be acknowledged. First, the concept of 'general patients' needs clarification. While the unit is officially designated as the Internal Medicine ICU, it functionally serves a wide array of critically ill patients from various non-surgical specialties. Nevertheless, the study population was derived from a single center and confined to this specific institutional setting, which inherently limits the generalization of our findings (particularly the PNI cutoff value) to specialized ICUs, such as surgical or neurosurgical units. Second, the retrospective, single-center design inherently introduces the risk of selection bias and unmeasured confounding variables. Although multivariate logistic regression was used, no specific advanced methods for confounding adjustment (e.g., propensity score matching) were employed, which is a significant constraint of this study. Third, the reliance on a single PNI measurement taken within the first 24 hours of ICU admission fails to capture the subsequent temporal changes in the patient's condition. The prognostic utility of dynamic PNI changes over the course of the ICU stay should be investigated in future prospective studies. Fourth, the claim that PNI can facilitate 'optimization of resource allocation' remains speculative, as this study provided no data on cost-effectiveness, clinical decision changes, or length of stay modifications based on PNI scores. Future prospective studies should incorporate dynamic PNI measurements to assess trends, compare PNI head-to-head with standard severity scores using incremental value metrics (NRI/IDI), and include diverse ICU populations to solidify its role in critical care prognostication.

Conclusion

PNI is a practical parameter derived from readily available routine laboratory parameters, which allows for rapid and integrated risk stratification in the ICU. Prediction of disease severity and mortality is essential to evaluate patients more precisely and to plan an appropriate treatment strategy.

Declarations

Ethics committee approval

Ethics committee number: 2025-01/05.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Financial disclosure

The authors received no financial support for this study.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study's design, execution, and data analysis, and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the study participants for their contributions.

References

2. Ceylan E, Itil O, Arı G, Ellidokuz H, Uçan ES, Akkoçlu A. Factors affecting mortality and morbidity in patients monitored in the internal medicine intensive care unit. Thoracic Journal. 2001;2:6–12.

3. Cevik MA, Yilmaz GR, Erdinc FS, Ucler S, Tulek NE. Relationship between nosocomial infection and mortality in a neurology intensive care unit in Turkey. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2005 Apr 1;59(4):324–30.

4. Unal AU, Kostek O, Takir M, Caklili O, Uzunlulu M, Oguz A. Prognosis of patients in a medical intensive care unit. North Clin Istanb. 2015 Dec 31;2(3):189–95.

5. Buzby GP, Mullen JL, Matthews DC, Hobbs CL, Rosato EF. Prognostic nutritional index in gastrointestinal surgery. Am J Surg. 1980 Jan;139(1):160–7.

6. Hayashi J, Uchida T, Ri S, Hamasaki A, Kuroda Y, Yamashita A, et al. Clinical significance of the prognostic nutritional index in patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020 Aug;68(8):774–9.

7. Keskin M, İpek G, Aldağ M, Altay S, Hayıroğlu Mİ, Börklü EB, et al. Effect of nutritional status on mortality in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Nutrition. 2018 Apr;48:82–6.

8. Ofluoğlu CB, Mülküt F, Aydın İC, Başdoğan MK, Aydın İ. Prognostic Nutritional Index as a Predictor of Surgical Morbidity in Total Neoadjuvant Therapy for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. J Clin Med. 2025 Mar 13;14(6):1937.

9. Huang Z, Fu Z, Huang W, Huang K. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in sepsis: A meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 Mar;38(3):641–7.

10. Eckart A, Struja T, Kutz A, Baumgartner A, Baumgartner T, Zurfluh S, et al. Relationship of Nutritional Status, Inflammation, and Serum Albumin Levels During Acute Illness: A Prospective Study. Am J Med. 2020 Jun;133(6):713–22.e7.

11. Sheinenzon A, Shehadeh M, Michelis R, Shaoul E, Ronen O. Serum albumin levels and inflammation. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021 Aug 1;184:857–62.

12. Arslan K, Celik S, Arslan HC, Sahin AS, Genc Y, Erturk C. Predictive value of prognostic nutritional index on postoperative intensive care requirement and mortality in geriatric hip fracture patients. North Clin Istanb. 2024 Jun 26;11(3):249–57.

13. Taşkın Ö, Demir U, Yılmaz A, Özcan S, Doğanay Z. Investigation of the relationship between prognostic nutrition index and mortality in patients with femur fracture. Journal of Contemporary Medicine. 2023;13(1):60–5.

14. Ushirozako H, Hasegawa T, Yamato Y, Yoshida G, Yasuda T, Banno T, et al. Does preoperative prognostic nutrition index predict surgical site infection after spine surgery? Eur Spine J. 2021 Jun;30(6):1765–73.

15. Hu Q, Wang G, Ren J, Ren H, Li G, Wu X, et al. Preoperative prognostic nutritional index predicts postoperative surgical site infections in gastrointestinal fistula patients undergoing bowel resections. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Jul;95(27):e4084.

16. Bion JF. Susceptibility to critical illness: reserve, response and therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26 Suppl 1:S57–63.