Abstract

Background: Equine strongyloidiasis is a widespread parasitic infection that poses a substantial health challenge to equine populations worldwide. This disease adversely affects animal welfare and incurs considerable economic losses, particularly in rural and peri-urban areas of Ethiopia. This study aims to determine the prevalence of Equine Strongyloidiasis and to identify the associated risk factors in and around Guder.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was undertaken from April to June 2018. A total of 420 equines were randomly selected based on species, age, body condition, altitude, and clinical history. Fecal samples were collected and examined for the presence of Strongyle eggs using standard parasitological techniques.

Results: The overall prevalence of Strongyloidiasis was found to be 73.3%, with donkeys exhibiting the highest infection rate (80%), followed by mules (69.5%) and horses (57.1%); however, differences among species were not statistically significant. The prevalence in female equines (65%) was higher than in males (35%), though this difference was not significant. Similarly, infection rates between young (75%) and adult (72.7%) animals did not differ significantly. Body condition showed a strong association with infection, as animals in poor condition had a significantly higher prevalence (96.5%) compared to those in medium (75%) and good (26.6%) condition. Additionally, draft equines had a significantly greater prevalence (80.9%) than transport equines (55.5%).

Conclusion: The observed results emphasize the necessity for targeted interventions aimed at enhancing animal health and management to effectively reduce the burden of strongyle infections. Therefore, it is essential to implement regular deworming programs, especially for equines with poor body condition and those used for draft purposes, along with improving nutrition and management practices. Moreover, raising awareness among owners about risk factors and encouraging proper pasture management are important. Further studies over different seasons are necessary to better understand infection patterns, and stronger cooperation between veterinary services and communities is needed to enhance diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords

Equine Strongyloidiasis, Strongyle infection, Prevalence, Risk factors, Cross-sectional study, Guder

Background

Equines, which include horses, donkeys, mules, and zebras, are large hoofed mammals characterized by long legs, strong hooves, and a diet primarily composed of grasses. These animals play an important role in ecosystems and have been closely connected to human societies throughout history [1]. They are used worldwide for various tasks such as carrying loads, riding, pulling carts, and ploughing fields. Their strength and endurance are especially valuable for transportation in rural and urban areas where road infrastructure is limited [2]. By facilitating the movement of people and goods, equines support the livelihoods of many rural and semi-urban communities, particularly in developing countries. Donkeys, in particular, contribute significantly to food security and social equity in regions experiencing food shortages [3,4].

Globally, the equine population is estimated at approximately 122.4 million animals, with Africa hosting around 17.6 million, including 11.6 million donkeys, 2.3 million mules, and 3.7 million horses [5,6]. Ethiopia has a similarly notable equine population estimated at 8.4 million, consisting of 5.02 million donkeys, 2.75 million horses, and 0.63 million mules [2].

Despite this large population, the productivity of equines in Ethiopia remains relatively low compared to many other countries. This gap is attributed to factors such as poor nutrition, reproductive challenges, management issues, and the prevalence of various diseases. Among the most common health problems are parasitic infections, especially equine Strongyloidiasis, which poses a serious threat [6,7].

Equine Strongyloidiasis is a widespread parasitic infection affecting equine health worldwide. It adversely impacts animal welfare and results in considerable economic losses, especially in rural and peri-urban areas of Ethiopia [8]. In locations with limited modern transportation options, equines remain essential for transporting agricultural and industrial goods [9].

The clinical signs of Strongyloidiasis include poor body condition, anemia, colic, and diarrhea, which can escalate to more severe complications such as arthritis and thrombosis [10–12]. The transmission of Strongyloidiasis is influenced by climatic factors and management practices, which complicates the application of a universal deworming approach [13]. Effective control requires targeted anthelmintic treatments tailored to local environmental and management conditions [6,14–16].

Several studies have documented the widespread prevalence of Equine Strongyloidiasis across Ethiopia. Researchers including Yoseph et al. [3], Fikru et al. [9], Ayele et al. [17], and Mezgebu et al. [8] emphasize the significant presence of this parasitic infection among Ethiopian equines. However, there is limited data regarding the prevalence and risk factors of this infection in Guder, which underscores the need for further research to better understand its local impact. Therefore, this study aims to determine the prevalence of Equine Strongyloidiasis and to identify the associated risk factors in and around Guder.

Materials and Methods

Study area

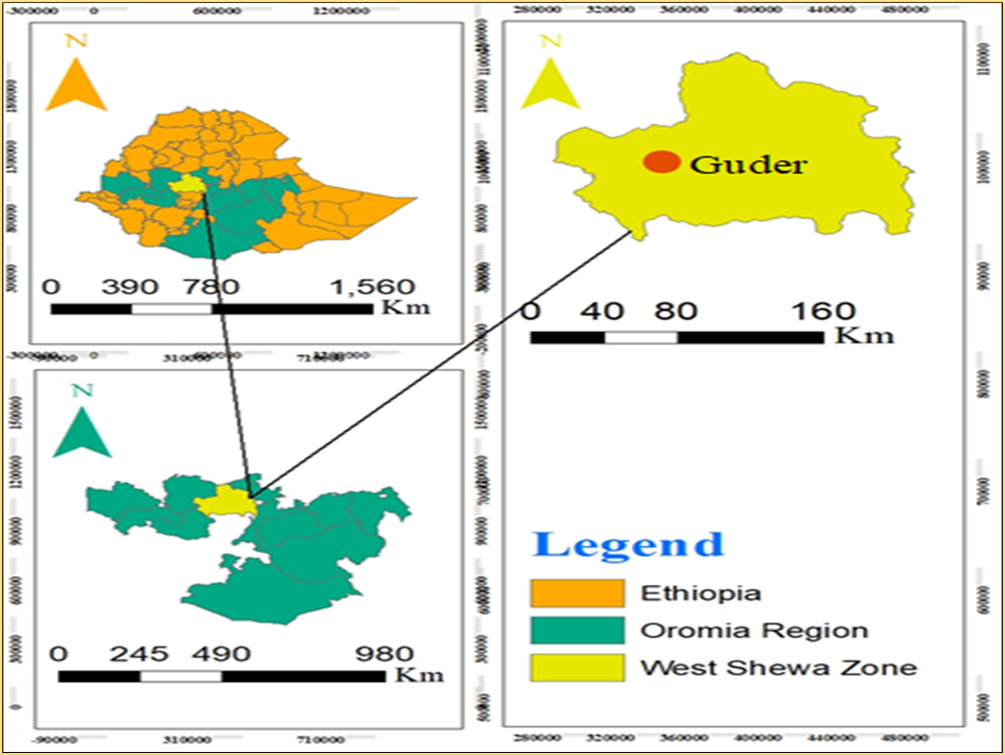

The study was conducted in Guder, located in the West Shewa Zone of the Oromia Regional State, approximately 137 kilometers west of the capital city (Figure 1). The Guder lies at an altitude ranging from 1,250 to 3,200 meters above sea level. The area experiences a bimodal rainfall pattern, with annual precipitation ranging between 800 and 1,100 millimeters. The climate is characterized by temperatures ranging from 16°C to 22°C, with rainfall occurring in two distinct seasons: a short rainy season from February to May and a longer rainy season from June to September. The town supports a diverse livestock population, including 145,460 cattle, 50,413 sheep and goats, 24,772 poultry, and 4,760 equines comprising horses, mules, and donkeys. The human population of the Guder is 134,767, consisting of 66,492 males and 68,275 females [18].

Figure1. Map of the study area.

Study animal and sampling method

The study animals consisted of equine species, including horses, donkeys, and mules, found in Guder. A total of 420 equines representing all age groups and both sexes were randomly selected after considering their history, species, body condition, altitude of the area, and approximate age. The average age of the equines was determined based on dentition and categorized as young or adult according to the method described by Cringoli et al. [19]. Body condition scores were recorded following the guidelines established by Nicholson and Butterworth [20].

Study design and sample size

A cross-sectional study was conducted from April to June 2018 to estimate the prevalence of Equine Strongyloidiasis and associated risk factors in the study area. All horses, mules, and donkeys presented to the clinic exhibiting clinical signs suggestive of strongyle infection were included in the study. Since there was no prior data available on the prevalence of Strongyloidiasis in the study area, the sample size for fecal sample collection was determined according to the guidelines provided by Thrusfield [21]. This calculation used a 95% confidence interval and 5% absolute precision, assuming an expected prevalence of 50%.

The initial sample size was calculated to be 384 using the formula where ???? represents the sample size, ????exp denotes the expected prevalence, and ???? stands for the desired absolute precision. To improve the accuracy of prevalence estimation, the sample size was increased to 420.

Fecal examination

Fecal samples were collected directly from the rectums of 420 suspected equines, including donkeys, mules, and horses, at the Guder Veterinary Clinic and surrounding areas. Each animal was properly restrained by its owner, and the examiner used disposable arm-length gloves to maintain hygiene. Veterinary-approved lubricant was applied before gently inserting gloved fingers into the rectum to minimize discomfort and prevent mucosal damage. A sufficient fecal sample was carefully obtained and placed into sterile, airtight vials to avoid contamination. Each sample was labeled with relevant information and promptly transported to the veterinary parasitology laboratory under optimal conditions to preserve parasite viability. Samples were processed on the same day; those requiring delayed examination were preserved in 10% formalin. The flotation technique was employed to separate parasitic elements, and microscopic examination at 10x and occasionally 40x magnification was performed to detect Strongyle eggs.

Data analysis

The raw data collected during the study were systematically organized and entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for efficient management and initial processing. Subsequent statistical analyses were performed using STATA Version 14.0. Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize the prevalence of equine Strongyloidiasis. The chi-square test was applied to assess associations between infection rates and various risk factors. A significance level of P<0.05 was adopted to determine statistical significance, indicating that observed differences were unlikely to occur by chance.

Result

Among the 420 equine fecal samples examined in the study, 308 tested positive for Strongyle eggs, resulting in an overall prevalence of 73.3% for Strongyle infections in the study area.

When stratified by species, donkeys exhibited the highest prevalence rate, with 80% of samples testing positive for strongyle eggs. This was followed by mules at 69.5%, and horses, which showed the lowest prevalence among the species at 57.1%. However, despite these apparent differences, statistical analysis revealed no significant differences in infection rates between donkeys, mules, and horses, indicating that species does not significantly influence the prevalence of strongyle infection (Table 1).

|

Species |

Examined |

Positive (%) |

χ² |

P-value |

|

Donkey |

210 |

168 (80%) |

2.22 |

0.330 |

|

Horse |

49 |

28 (57.1%) |

||

|

Mule |

161 |

112 (69.5%) |

||

|

Total |

420 |

308 (73.3%) |

Sex-based differences were also assessed, with female equines showing a prevalence rate of 65%, while male equines had a lower rate of 35%. However, the difference in prevalence between sexes was not statistically significant (Table 2).

|

Sex |

Examined |

Positive (%) |

χ² |

P-value |

|

Female |

280 |

182 (65%) |

1.26 |

0.262 |

|

Male |

140 |

49 (35%) |

||

|

Total |

420 |

308 (73.3%) |

Age appeared to be another less influential factor, as young equines had a prevalence rate of 75%, compared to 72.7% in adults. Statistical analysis also found no significant difference in infection rates between young and adult equines (Table 3).

|

Age |

Examined |

Positive (%) |

χ² |

P-value |

|

Adult |

308 |

224 (72.7%) |

0.032 |

0.857 |

|

Young |

112 |

84 (75%) |

||

|

Total |

420 |

308 (73.3%) |

Body condition was identified as a key factor in the prevalence of Strongyle infections. Equines in poor body condition had a significantly higher prevalence rate of 96.5%, compared to those in medium body condition (75%). Equines in good condition showed a markedly lower prevalence of 26.6%. The differences in infection rates between these body condition categories were statistically significant (Table 4).

|

Body Condition |

Examined |

Positive (%) |

χ² |

P-value |

|

Good |

105 |

28 (26.6%) |

10.44 |

0.000 |

|

Medium |

112 |

84 (75%) |

||

|

Poor |

203 |

196 (96.5%) |

||

|

Total |

420 |

308 (73.3%) |

Additionally, the type of work performed by equines was found to be associated with significant variations in infection rates. Draft (working) equines had a prevalence rate of 80.9%, whereas transport equines had a lower rate of 55.5%. The observed difference between these two groups was statistically significant (p<0.05), suggesting that the type of work performed may influence the likelihood of Strongyle infection (Table 5).

|

Purpose |

Examined |

Positive (%) |

χ² |

P-value |

|

Draft |

294 |

238 (80.9%) |

5.76 |

0.016 |

|

Transport |

126 |

70 (55.5%) |

||

|

Total |

420 |

308 (73.3%) |

Discussion

The study examined the prevalence of Strongyle infections in 420 equine fecal samples, revealing an overall prevalence of 73.3%, which is higher than those reported by Molla et al. [22] and Addis et al. [23], but lower than rates recorded in some earlier studies. For instance, Ayele and Dinka [24] reported Strongyle prevalence rates of 93% in Bereh, 87% in Boset, and 95% in Adaa, while Getachew et al. [2] observed even higher rates, including 100% in East Shewa and 99% in Adaa, Akaki, and Bost of East Shewa. These discrepancies across studies may stem from differences in environmental conditions (e.g., altitude, temperature, and rainfall), sample sizes, seasonal variation in sampling, management systems, access to veterinary services, and the use of anthelmintic treatments [25].

In terms of species-specific prevalence, donkeys had the highest infection rate at 80%, followed by mules at 69.5%, and horses at 57.1%. Although variation was observed among the three species, statistical analysis revealed no significant difference, suggesting that species alone is not a major determinant of infection risk. These findings are comparatively lower than those reported by Yoseph et al. [3], Ayele et al. [17], Fikru et al. [9], and Mezgebu et al. [8], who documented prevalence rates of up to 100% in donkeys from different regions of Ethiopia, including Wonchi, Wollo, and the western highlands of Oromia and Gonder. Such differences are likely due to agro-ecological variation, differences in animal husbandry, and the implementation of deworming programs [26,27].

The prevalence of Strongyle infection was also assessed by sex. Female equines exhibited a prevalence rate of 65%, while male equines showed 35%. Although the prevalence was higher in females, the difference was not statistically significant. These findings are consistent with studies by Fikru et al. [9] and Yoseph et al. [3], which also reported no significant sex-based differences. However, they contrast with the findings of Saeed et al. [28] and Basaznew et al. [29], who found significantly higher prevalence in females. The variation might be due to gender-specific management practices, where males often perform heavier work and receive supplementary feeding, while females may graze more frequently and receive less consistent deworming, thereby increasing their risk of exposure to infective larvae [27,30].

With respect to age, young equines had a prevalence of 75%, slightly higher than 72.7% in adults. However, this difference was also not statistically significant. This supports the findings of Soulsby [31], who noted that younger animals are typically more susceptible to parasitic infections due to their developing immune systems. Nevertheless, studies such as Getachew et al. [2] reported notable variation in prevalence across age groups. These inconsistencies could be due to management differences, such as age-based separation during grazing, or improved health interventions and deworming protocols targeted at younger animals in certain regions [32].

Body condition emerged as a major risk factor for Strongyle infection. Equines in poor condition showed a substantially higher prevalence at 96.5%, compared to 75% in those with medium condition, and only 26.6% in animals with good condition. The differences in prevalence based on body condition were statistically significant, indicating a strong association between poor physical status and increased risk of infection. This finding aligns with Ayele et al. [17], who demonstrated that equines in poor nutritional and physical status are more susceptible to parasitic infections. Malnutrition, overwork, and insufficient veterinary care compromise the animal’s immune response, increasing vulnerability. In contrast, equines in good body condition, likely benefiting from better feeding and regular deworming, exhibited significantly lower infection rates [33,34].

Finally, the purpose of equine use influenced infection prevalence. Equines used for draft work exhibited a higher prevalence of 80.9%, whereas those used for transport showed a lower prevalence of 55.5%. This statistically significant difference suggests that working conditions and management practices play a key role in exposure risk. This observation agrees with Addis et al. [23], who also reported higher infection rates in working equines. Draft animals are generally more exposed to unsanitary environments, communal grazing, and prolonged outdoor activities, increasing their contact with infective larvae. In contrast, transport animals may experience more regulated workloads, better housing, and more frequent veterinary attention, including deworming, which can contribute to reduced infection rates [35,36].

Conclusion

This study revealed a high overall prevalence of Equine Strongyloidiasis (73.3%) in the study area, showing that the infection is a significant health concern for the local equine population. Although there were no statistically significant differences in prevalence among species, sex, and age groups, body condition and the purpose of the equines were significantly related to infection rates. Equines in poor body condition and those used for draft work had notably higher prevalence, indicating that these factors play an important role in susceptibility. The observed results emphasize the necessity for targeted interventions aimed at enhancing animal health and management to effectively reduce the burden of Strongyle infections. Therefore, it is essential to implement regular deworming programs, especially for equines with poor body condition and those used for draft purposes, along with improving nutrition and management practices. Moreover, raising awareness among owners about risk factors and encouraging proper pasture management are important. Further studies over different seasons are necessary to better understand infection patterns, and stronger cooperation between veterinary services and communities is needed to enhance diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff members of the Guder Veterinary Clinic and those in the surrounding area. Their unwavering support was instrumental in the successful completion of this study.

Author Contributions

Z.G.W: Writing the original draft, resources, methodology, validation, visualization, investigation, conceptualization, reviewing and editing, and formal analysis. A.B.T: Writing the original draft, resources, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, validation, visualization, reviewing and editing, supervision, and data curation. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

None.

References

2. Getachew M, Feseha G, Trawford A, Reid SW. A survey of seasonal patterns in strongyle faecal worm egg counts of working equids of the central midlands and lowlands, Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2008 Dec;40(8):637–42.

3. Yoseph S, Smith DG, Mengistu A, Teklu F, Firew T, Betere Y. Seasonal variation in the parasite burden and body condition of working donkeys in East Shewa and West Shewa regions of Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2005 Nov;37 Suppl 1:35–45.

4. Woodford MH. Veterinary aspects of ecological monitoring: the natural history of emerging infectious diseases of humans, domestic animals and wildlife. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2009 Oct;41(7):1023–33.

5. Abayneh T, Gebreab F, Zekarias B, Tadesse G. The potential role of donkeys in land tillage in Central Ethiopia. Bull Anim Health Prod Afr. 2002;50:172–8.

6. Chapman MR, French DD, Klei TR. Gastrointestinal helminths of ponies in Louisiana: a comparison of species currently prevalent with those present 20 years ago. J Parasitol. 2002 Dec;88(6):1130–4.

7. Stratford CH, McGorum BC, Pickles KJ, Matthews JB. An update on cyathostomins: anthelmintic resistance and diagnostic tools. Equine Vet J Suppl. 2011 Aug;(39):133–9.

8. Tola Mezgebu TM, Ketema Tafess KT, Firaol Tamiru FT. Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites of horses and donkeys in and around Gondar town, Ethiopia. Open J Vet Med. 2013;3(6):267–1.

9. Fikru R, Reta D, Teshale S, Bizunesh M. Prevalence of equine gastrointestinal parasites in Western highlands of Oromia. Bulletin of Animal Health and Production in Africa. 2005 Oct 11;53(3):161–6.

10. Miller WC. The general problem of parasitic infestation in horses. CABI Databases. 1953:213–6.

11. Duncan JL. The life cycle, pathogenisis and epidemiology of S. vulgaris in the horse. Equine Vet J. 1973 Jan;5(1):20–5.

12. Drudge JH, Lyons ET. Pathology of infections with internal parasites in horses. CABI Databases. 1977:267–75.

13. Dunsmore JD, Jue Sue LP. Prevalence and epidemiology of the major gastrointestinal parasites of horses in Perth, Western Australia. Equine Vet J. 1985 May;17(3):208–13.

14. Dennis VA, Klei TR, Miller MA, Chapman MR, McClure JR. Immune responses of pony foals during repeated infections of Strongylus vulgaris and regular ivermectin treatments. Vet Parasitol. 1992 Apr;42(1-2):83–99.

15. Eysker M, Boersema JH, Grinwis GC, Kooyman FN, Poot J. Controlled dose confirmation study of a 2% moxidectin equine gel against equine internal parasites in The Netherlands. Vet Parasitol. 1997 Jun;70(1-3):165–73.

16. Eysker M, Jansen J, Kooyman FN, Mirck MH, Wensing T. Comparison of two control systems for cyathostome infections in the horse and further aspects of the epidemiology of these infections. Vet Parasitol. 1986 Nov;22(1-2):105–12.

17. Ayele G, Feseha G, Bojia E, Joe A. Prevalence of gastro-intestinal parasites of donkeys in Dugda Bora District, Ethiopia. Livestock Research for Rural Development. 2006 Nov 8;18(10):14–21.

18. Deresa F, Legesse T. Cause of land degradation and its impacts on livelihoods of the population in Toke Kutaye Woreda, Ethiopia. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications. 2015 May;5(5):1–9.

19. Cringoli G, Rinaldi L, Capuano F, Baldi L, Veneziano V, Capelli G. Serological survey of Neospora caninum and Leishmania infantum co-infection in dogs. Vet Parasitol. 2002 Jul 2;106(4):307–13.

20. Nicholson MJ, Butterworth MH. A guide to condition scoring of zebu cattle. ILRI (aka ILCA and ILRAD); 1986. pp. 3–31.

21. Thrusfield M. Veterinary epidemiology 2nd ed. Black Well Science Ltd. UK. 1995. pp. 312–21.

22. Molla B, Worku Y, Shewaye A, Mamo A. Prevalence of strongyle infection and associated risk factors in equine in Menz Keya Gerbil District, North-Eastern Ethiopia. Journal of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Health. 2015 Apr 30;7(4):117–21.

23. Addis H, Gizaw TT, Minalu BA, Tefera Y. Cross-sectional study on the prevalence of equine strongyle infection Inmecha Woreda, Ethiopia. Int J Adv Res Biol Sci. 2017;4(8):68–77.

24. Ayele G, Dinka A. Study on strongyles and parascaris parasites population in working donkeys of central Shoa, Ethiopia. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2010;22(12):1–5.

25. Nielsen MK, Branan MA, Wiedenheft AM, Digianantonio R, Scare JA, Bellaw JL, et al. Risk factors associated with strongylid egg count prevalence and abundance in the United States equine population. Vet Parasitol. 2018 Jun 15;257:58–68.

26. Sallé G, Cabaret J. A survey on parasite management by equine veterinarians highlights the need for a regulation change. Vet Rec Open. 2015 Sep 14;2(2):e000104.

27. Thamsborg SM, Ketzis J, Horii Y, Matthews JB. Strongyloides spp. infections of veterinary importance. Parasitology. 2017 Mar;144(3):274–84.

28. Saeed K, Qadir Z, Ashraf K, Ahmad N. Role of intrinsic and extrinsic epidemiological factors on strongylosis in horses. J Anim Plant Sci. 2010;20(4):277–80.

29. Basaznew Bogale BB, Zelalem Sisay ZS, Mersha Chanie MC. Strongyle nematode infections of donkeys and mules in and around Bahirdar, Northwest Ethiopia. CABI Databases. 2012:497–501.

30. Esatgil MU, Efil II. A coprological study of helminth infections of horses in Istanbul, Turkey. Kafkas Univ Vet Fak Derg. 2012 May 1;18:1–6.

31. Soulsby EJ. Helminths, arthropods and protozoa of domesticated animals. 7th ed. 1982. pp. 809.

32. Bogale B, Sisay Z, Chanie M. Strongyle nematode infections of donkeys and mules in and around Bahirdar, Northwest Ethiopia. Glob Veterinaria. 2012;9(4):497–501.

33. Karki S, Chetri DK. Prevalence of Gastrointestinal Helminths in Equines of Chitwan District. Nepalese Vet J. 2013;32:134–40.

34. Maria A, Shahardar RA, Bushra M. Prevalence of gastrointestinal helminth parasites of equines in central zone of Kashmir Valley. Indian J Anim Sci. 2012 Nov 1;82(11):1276–80.

35. Nielsen MK, Fritzen B, Duncan JL, Guillot J, Eysker M, Dorchies P, et al. Practical aspects of equine parasite control: a review based upon a workshop discussion consensus. Equine Vet J. 2010 Jul;42(5):460–8.

36. Nielsen MK, Pfister K, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G. Selective therapy in equine parasite control--application and limitations. Vet Parasitol. 2014 May 28;202(3-4):95–103.