Abstract

Background: Poultry is raised globally in both backyard and commercial systems, with fewer social and religious taboos compared to other livestock species. However, the poultry industry faces significant challenges due to gastrointestinal (GI) nematode parasites, which can compromise productivity and health. In Ethiopia, where poultry play a critical role in rural livelihoods, parasitic infections such as Ascaridia galli remain a persistent concern. This study was conducted to estimate the prevalence of GI nematode infections in chicken and to identify associated risk factors in selected poultry farms in and around Ambo, Ethiopia.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was carried out from April to June 2019 using a random sampling technique. A total of 70 fecal samples were collected from chicken of varying body condition scores, ages, sexes, and locations. Standard parasitological techniques were employed to detect the presence of nematode eggs in fecal matter. Data were analyzed to assess the association of infection with potential risk factors, including age, sex, body condition, and farm location.

Results: The overall prevalence of gastrointestinal nematode infections was 60%. Chicken with poor body condition exhibited the highest infection rate (78.57%), followed by those in medium (54.54%) and good (40%) condition, with the difference being statistically significant. Age showed a strong association with infection, as adults had a significantly higher prevalence (92.85%) compared to young chicken (38.09%). Although male chicken had a slightly higher infection rate (61.53%) than females (56.14%), the difference was not statistically significant. Significant variation was also observed across different farm locations: Ambo University Poultry Farm reported the highest prevalence (83.87%), followed by Abebe Private Farm (55%) and Guder Campus Poultry Farm (26.31%) (P<0.05).

Conclusion: The observed findings underscore the significance of implementing routine deworming protocols, optimizing nutritional management, and enhancing biosecurity measures to effectively control gastrointestinal nematode infections. Moreover, further research is essential to examine seasonal dynamics and to develop robust surveillance systems that facilitate sustainable parasite control initiatives.

Keywords

Ambo, Chicken, Cross-sectional study, Gastrointestinal Nematode, Prevalence

Background

Poultry is kept in backyards or commercial production systems in most areas of the world. Compared to a number of other livestock species, fewer social and religious taboos are related to the production, marketing, and consumption of poultry products. For these reasons, poultry products have become one of the most important protein sources for humans throughout the world [1,2]. In developing countries, poultry production offers an opportunity to feed the fast-growing human population and to provide income resources for poor farmers. Moreover, poultry in many parts of the modern world are considered as the chief source of not only cheaper protein of animal origin but also high-quality human food [3].

Among the important species of livestock kept in Ethiopia, poultry production systems are identified in the country. These include backyard poultry production systems, small-scale, and large-scale intensive production systems [4]. The population of poultry in Ethiopia is estimated to be 44.89 million, excluding the pastoral and agro-pastoral areas. With regard to breed, 96.46%, 0.57%, and 2.97% of the total poultry are reported to be indigenous, hybrid, and exotic, respectively [5]. Despite the presence of a large number of Chicken in Ethiopia, the contribution to the national economy or the exploited benefit is very limited due to nutritional limitations and diseases [6].

Among parasitic diseases of poultry, nematode parasites are one of the major problems of the chicken industry worldwide, characterized by riffled feathers, loss of appetite, poor growth, and reduced egg production [7]. Moreover, nematodes (roundworms) are the most important group of helminth parasites of poultry. This is due to the large number of parasitic species that cause damage to the host, especially in severe infections. Most roundworms affect the gastrointestinal tract, with occasional parasites affecting the trachea or eye. Each species of roundworm tends to infect a specific area of the gastrointestinal tract. Different species of the same genus may infect several different areas of the tract. In general, the different species of roundworms have very similar life cycles [8]. Of the helminth parasites of poultry birds, nematodes constitute the most important group of helminth parasites of poultry, both in the number of species and the extent of damage they cause; the main genera include Ascaridia and Heterakis [9].

Generally, nematode infections in poultry are widely distributed in different parts of the world, and numerous research efforts have been undertaken to prevent poultry mortality from parasitic diseases. The prevalence of two nematode genera, Ascaridia and Heterakis, has been extensively studied [10]. Among diseases, internal parasites are known to reduce the productivity of poultry kept under various management systems. Infection by parasites occurs after ingestion of nematode eggs or intermediate hosts such as cockroaches, grasshoppers, ants, and earthworms. Nematode infection results in a reduction in food intake, injury to the intestinal wall, and hemorrhage, leading to poor absorption of nutrients and weight loss [11].

Gastrointestinal parasite infestation is a common problem in poultry, especially when nematode infections occur in high proportions in animals reared in intensive management systems. In Ethiopia, the poultry industry is developing for both local and exotic Chicken, but only a few surveys have been carried out to determine the burden of nematode parasites in Chicken in this country [12,13]. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to estimate the prevalence of major gastrointestinal nematode parasites in poultry and to assess the risk factors associated with the incidence of the parasites in the study area.

Materials and Methods

Study area

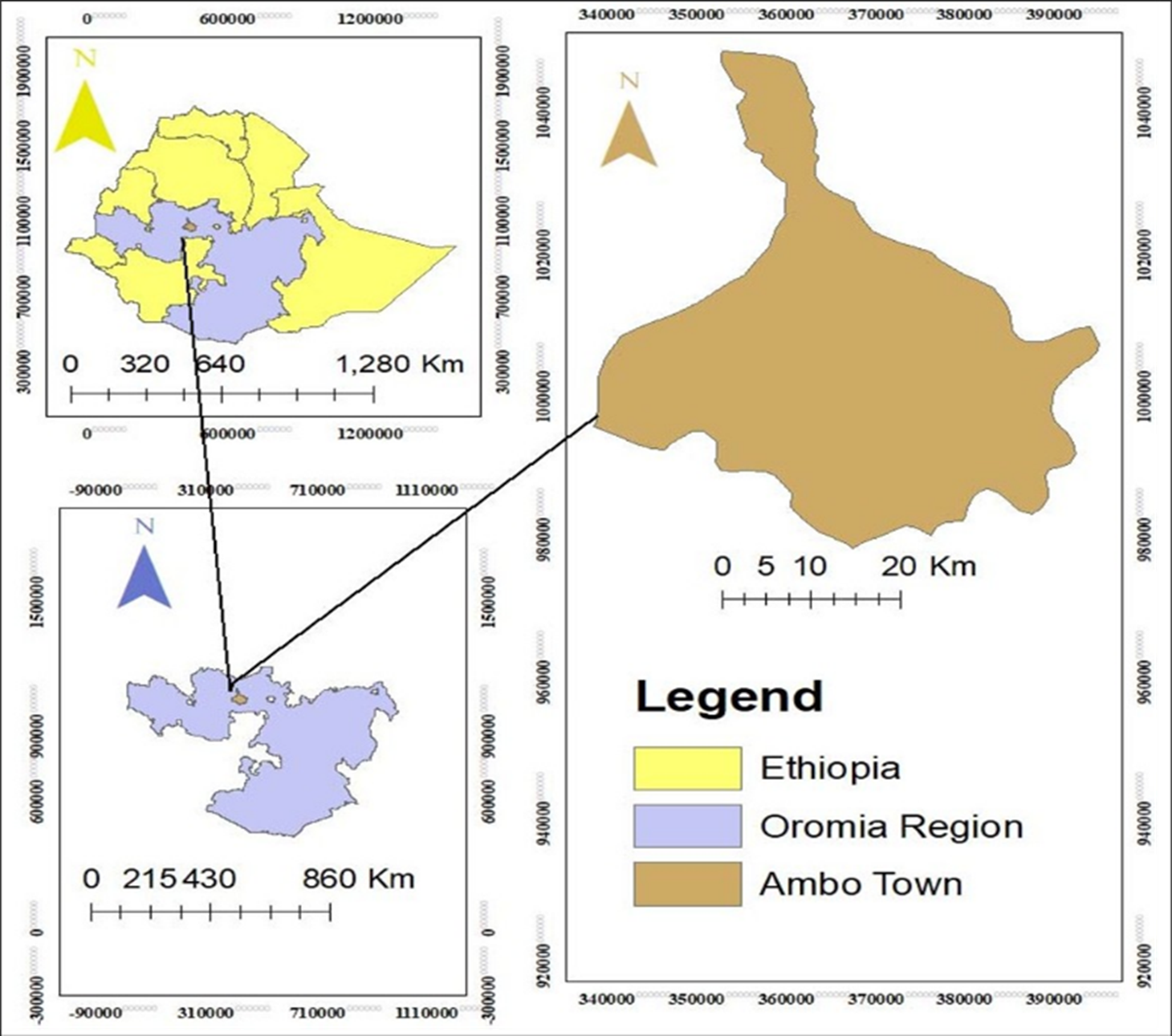

The study was conducted on selected poultry farms in and around Ambo, Ethiopia, from April to June 2019. Ambo, the administrative center of the West Shewa Zone, is situated at 8°59′N latitude and 37°51′E longitude, at an altitude of 2,101 meters above sea level and approximately 114 km west of Addis Ababa (Figure 1). Ambo Woreda comprises 34 administrative kebeles. The agro-ecology of the area is characterized by 23% highland, 60% midland, and 17% lowland zones. The region experiences an annual rainfall of 800–1,000 mm and a temperature range of 20–29°C. The livestock population includes approximately 145,371 cattle, 50,152 sheep, 27,026 goats, 105,794 chicken, 9,088 horses, 2,914 donkeys, and 256 mules [14].

Figure 1. Map of the study area.

Study population

The study populations included all exotic breeds’ Chicken of both sexes and all age groups that were kept under intensive management systems from the selected intensive farms. The birds were categorized into two age groups: Young (under 12 months) and adult (above 12 months of age). The age of the birds was determined from records found on the farm and subjectively based on the size of the crown, length of the spur, and so on [15].

Study design and sample size determination

A cross-sectional study design was used for this study. Sex, different age groups, body condition, breed, and management systems were recorded as test variables during the data collection of target Chicken. A random sampling technique was used to recruit animals for the study. The required sample size for this study was estimated according to the formula of [16], with an expected prevalence of 68.5% from a previous study conducted by [13] in a comparable agro-ecological area, and a desired absolute precision (d) of 0.05 at a 95% confidence level.

Where ???? represents the required sample size, ????exp denotes the expected prevalence, and ???? stands for the desired absolute precision. Using this formula, the sample size was calculated to be 332. However, only 70 Chicken were selected purposefully due to a shortage of time.

Data collection

After examining the selected Chicken for general body condition and clinical signs indicative of gastrointestinal nematodes, samples were taken and entered into the Ambo University Department of Veterinary Laboratory Technology laboratory for parasitological examinations. Fecal samples were collected using hand gloves directly from the vent or top surface of freshly voided feces and placed in airtight screw-cap universal bottles. The samples were transported to the Parasitology laboratory of Ambo University, College of Veterinary Laboratory Technology, and stored at 4°C until examination. During sample collection, information about risk factors such as body condition, sex, age, and all other management systems were recorded for each collected sample. Samples were processed using the floatation technique as described by [17].

Data management and analysis

The raw data gathered for the study were entered into a Microsoft Excel database and organized using the Excel spreadsheet program. Subsequently, the data were imported into STATA Version 18.0 for analysis. A chi-square (χ2) test was employed to evaluate the statistical association between infection rates and various factors. A significance level of p<0.05 at a 95% confidence interval was used to determine statistical significance between variables.

Results

In this study, a total of 70 chicken fecal samples were analyzed for gastrointestinal (GI) nematode infections, and the results revealed that 42 (60.0%) were positive for nematode eggs. The prevalence of infection varied significantly with body condition. Chicken in poor body condition had the highest prevalence at 78.57%, followed by those in medium condition at 54.54%, and those in good condition at 40% (Table 1). A statistically significant difference in prevalence was also observed among different locations, with the highest prevalence at Ambo University Poultry Farm (83.87%), followed by Abebe Private Farm (55%), and Guder Campus Poultry Farm (26.31%) (Table 1).

|

Factors |

Category |

Examined |

Positive |

χ2 |

P-value |

|

Sex |

Female |

57 |

34 (59.64%) |

0.016 |

0.900 |

|

Male |

13 |

8 (61.53%) |

|||

|

Age |

Young |

42 |

16 (38.09%) |

20.992 |

0.000 |

|

Adult |

28 |

26 (92.85%) |

|||

|

Abebe private |

20 |

11 (55%) |

|||

|

Place (Farm) |

Ambo university |

31 |

26 (83.87%) |

16.55 |

0.000 |

|

Guder campus |

19 |

5 (26.31%) |

|||

|

Body condition |

Poor |

28 |

22 (78.57%) |

7.630 |

0.022 |

|

Medium |

22 |

12 (54.54%) |

|||

|

Good |

20 |

8 (40%) |

|||

|

Total |

|

70 |

42 (60.0%) |

|

|

The overall prevalence of Ascaridia galli was 57.1%, and Heterakis gallinarum was 2.9%. The infestation rates of these nematodes varied significantly with sex, age, location, and body condition. Males had a slightly higher infestation rate of Ascaridia galli (61.53%) compared to females (56.14%), while Heterakis gallinarum was only observed in females (3.51%) (Table 2). In terms of age, adults exhibited a significantly higher infestation rate of Ascaridia galli (85.71%) compared to younger Chicken (38.09%). Adults also showed some infestation of Heterakis gallinarum (7.14%), which was absent in young Chicken (Table 2).

|

Factors |

Category |

Examined |

Nematode spp |

χ2 |

P-value |

|

|

Ascaridia galli |

Heterakis Gallinarum |

|||||

|

Sex |

Female |

57 |

32 (56.14%) |

2 (3.51%) |

0.520 |

0.771 |

|

Male |

13 |

8 (61.53%) |

0 (0%) |

|||

|

Age |

Young |

42 |

16 (38.09%) |

0 (0%) |

22.262 |

0.000 |

|

Adult |

28 |

24 (85.71%) |

2 (7.14) |

|||

|

Place (Farm) |

Abebe private |

20 |

11 (55%) |

0 (0%) |

17.853 |

0.001 |

|

Ambo university |

31 |

24 (77.41%) |

2 (6.45%) |

|||

|

Guder campus |

19 |

5 (26.31%) |

0(0%) |

|||

|

Body condition |

Poor |

28 |

20 (71.42%) |

2 (7.14%) |

9.632 |

0.047 |

|

Medium |

22 |

12 (54.54%) |

0 (0%) |

|||

|

Good |

20 |

8 (40%) |

0 (0%) |

|||

|

Total |

|

70 |

40 (57.1%) |

2 (2.9%) |

|

|

Location also played a significant role in the prevalence of these nematodes. Chicken from Ambo University Poultry Farm had the highest infestation rates for Ascaridia galli (77.41%) and Heterakis gallinarum (6.45%), while those from Guder Campus had the lowest rates for both parasites (26.31% and 0%, respectively) (Table 2). Chicken in poor body condition were the most affected, showing the highest infestation rates for both Ascaridia galli (71.42%) and Heterakis gallinarum (7.14%), while Chicken in good condition had the lowest rates for both nematodes (Table 2).

Discussion

The present study revealed that the overall prevalence of gastrointestinal (GI) nematode infection in Chicken was 60.0%, indicating a high burden of parasitic infestation in the study area. This prevalence was slightly higher than previous reports by [9], who found a prevalence of 59.64% in Ethiopia and 53% in Nigeria. However, it was lower than findings from [18] and [19], who reported rates of 61.9% and 64.7% in Nigeria and the Oromia region of Ethiopia, respectively. Furthermore, the result was lower than the 68.5% prevalence reported by [13] from the same area (Ambo, West Shoa Zone, Oromia Regional State). These variations in prevalence may be attributed to differences in management systems, study methodologies, sample size, environmental factors, and control practices.

Regarding the sex of the Chicken, females showed a prevalence of 59.64% while males had a slightly higher rate of 61.53%. Despite this, the difference was not statistically significant (χ²=0.016, P>0.05). This observation aligns with findings from [9,20], who also reported higher infection rates in female Chicken, potentially due to their increased feeding behavior during egg production. Conversely, this result contradicts the study by [21] in Haromaya, which reported a higher prevalence in males (52.1%) than in females (39.9%). Such discrepancies could be related to differences in nutritional status and sample size. Supporting this view, [22] indicated that GI nematode species typically do not show a specific affinity to either sex.

The study also demonstrated a statistically significant difference (P<0.05) in infection rates between age groups. Adult Chicken had a markedly higher prevalence of 92.85% compared to 38.09% in younger Chicken. This might be due to the prolonged exposure of adult Chicken to infective larval stages over time. This finding is consistent with the report of [23], whereas [17] and [24] reported a higher prevalence in younger Chicken, possibly due to their underdeveloped immune systems.

Among the identified nematode species, Ascaridia galli was the most prevalent, with a rate of 57.1%. This prevalence was higher than the 55.26% and 38.0% reported by [25] and [21] from central Ethiopia and Haromaya, respectively. The observed difference could be due to variations in deworming frequency, environmental hygiene, and agro-ecological conditions. The high prevalence might also be linked to the timing of the study during the wet season, which favors parasite survival and transmission. In contrast, Heterakis gallinarum was found at a lower prevalence of 2.9%. This was lower than the 4.3% reported by [26] in Ethiopia but higher than the 1.43% reported in Kenya [27]. Nevertheless, the current prevalence was significantly lower than the 51.6% reported by [28], likely due to agro-ecological differences.

Conclusion

This study identified a substantial prevalence of gastrointestinal nematodes, particularly Ascaridia galli, in chicken in the study area. The occurrence of infection was significantly associated with body condition, age, sex, and farm location. The observed findings underscore the significance of implementing routine deworming protocols, optimizing nutritional management, and enhancing biosecurity measures to effectively control gastrointestinal nematode infections. Moreover, further research is essential to examine seasonal dynamics and to develop robust surveillance systems that facilitate sustainable parasite control initiatives.

Author’s Contribution

SA: writing the original draft, resources, methodology, validation, visualization, investigation, conceptualization, reviewing and editing, and formal analysis; ZGW and TS: contributed to writing the original draft, resources, methodology, validation, visualization, investigation, reviewing and editing; ABT: contributed to writing the original draft, resources, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, validation, visualization, reviewing and editing, supervision, and data curation.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

None.

References

2. Simon MS, Emeritus S. Enteric diseases. In: ASA handbook on poultry diseases. 2nd ed. American Soybean Association; 2005. p. 133–143.

3. Central Statistical Agency (CSA). Volume II: Report on livestock and livestock characteristics (private peasant holdings) (Statistical Bulletin 468). Addis Ababa: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia; 2009. Available from: http://www.csa.gov.et/.

4. Yami A, Tadella D. The status of poultry research and development in Ethiopia. DZARC Res Bull. 1997;4:40–46.

5. Central Statistical Agency (CSA). Volume II: Report on livestock and livestock characteristics (private peasant holdings) (Statistical Bulletin 570). Addis Ababa: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia; 2012. Available from: http://www.csa.gov.et/.

6. Smith AJ. Poultry. The tropical agriculturalist. Hong Kong: Macmillan publisher; 1990. pp. 162–78.

7. Aiello S, Mays A. The Merck veterinary manual. 8th ed. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck and Co. Inc.; 1998.

8. Belete A, Addis M, Ayele M. Review on major gastrointestinal parasites that affect chickens. Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare. 2016;6(11):11–21.

9. Matur BM, Dawam NN, Malann YD. Gastrointestinal helminth parasites of local and exotic chickens slaughtered in Gwagwalada, Abuja (FCT), Nigeria. New York Science Journal. 2010;3(5):96–9.

10. Mulugeta A, Chanie M, Bogale B. Major constraints of village poultry production in Demba Gofa District of Southern Region, Ethiopia. British Journal of Poultry Sciences. 2013;2(1):1–6.

11. Soulsby EJ. Helminths, arthropods and protozoa of domesticated animals. 7th ed. London: Bailliere Tindall; 1986.

12. Oljira D, Melaku A, Bogale B. Prevalence and risk factors of coccidiosis in poultry farms in and around Ambo Town, Western Ethiopia. American-Eurasian Journal of Scientific Research. 2012;7(4):146–9.

13. Shiferaw S, Tamiru F, Gizaw A, Atalel D, Terfa W, Dandecha M, et al. Study on prevalence of helminthes of local backyard and exotic chickens in and around Ambowest Shoa Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. J Veter Sci Med. 2016;4(2):4.

14. Ambo Town Ministry of Agricultural Office (ATMA). Annual report. Ambo, Ethiopia; 2010.

15. Damerow G. Storey’s guide to raising chicken. USA: Storey Books; 1995.

16. Thrusfield M. Veterinary epidemiology. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1995.

17. Permin A, Hansen JW. Epidemiology, diagnosis and control of poultry parasites. 1998.

18. Luka SA, Ndams IS. Short communication report: Gastrointestinal parasites of domestic chicken Gallus-gallus domesticus linnaeus 1758 in Samaru, Zaria Nigeria. Science World Journal. 2007;2(1):27.

19. Tolossa Y, Shafi Z, Basu A. Ectoparasites and gastrointestinal helminths of chickens of three agro-climatic zones in Oromia Region, Ethiopia. Animal Biology. 2009 Jan 1;59(3):289–97.

20. Sonaiya EB. The context and prospects for development of smallholder rural poultry production in Africa. In: Proc CTA Int Sem Small Holder Rural Poultry Prod. Thessaloniki, Greece; 1990. Vol. 1. p. 35–52.

21. Tesfaheywet Z, Amare E, Hailu Z. Helminthosis of chickens in selected small scale commercial poultry farms in and around Haramaya Woreda, Southeastern Ethiopia. Journal of Veterinary Advances. 2012;2(9):462–8.

22. Hassouni T, Belghyti D. Distribution of gastrointestinal helminths in chicken farms in the Gharb region—Morocco. Parasitology Research. 2006 Jul;99(2):181–3.

23. Mekuria S, Bayessa M. Gastrointestinal helminths and their predisposing factors in different poultry management systems; Haromaya, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Veterinary Journal. 2017 Sep 11;21(1):40–53.

24. Mungube EO, Bauni SM, Tenhagen BA, Wamae LW, Nzioka SM, Muhammed L, et al. Prevalence of parasites of the local scavenging chickens in a selected semi-arid zone of Eastern Kenya. Tropical Animal Health and Production. 2008 Feb;40(2):101–9.

25. Ashenafi H, Eshetu Y. Study on gastrointestinal helminths of local chickens in Central Ethiopia. J Vet Med. 2004;155:504–7.

26. Eshetu Y, Mulualem E, Ibrahim H, Berhanu A, Aberra. Study of gastrointestinal helminths of scavenging chicken in four rural districts of Amhara. Ethiopian Agricultural Research Organization (EARO), National Poultry Research Program: Strategy Document. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 1999.

27. Kaingu FB, Kibor AC, Shivairo R, Kutima H, Okeno TO, Waihenya R, et al. Prevalence of gastro-intestinal helminthes and coccidia in indigenous chicken from different agro-climatic zones in Kenya. African journal of Agricultural Research. 2010 Mar 18;5(6):458–62.

28. Berhanu Mekibib BM, Haileyesus Dejene HD, Desie Sheferaw DS. Gastrointestinal helminthes of scavenging chickens in outskirts of Hawassa, Southern Ethiopia. Glob Vet. 2014;12:557–61.