Abstract

Background: Kearns-Sayre syndrome (KSS) is a rare mitochondrial DNA deletion disorder presenting before the age of 20 years, characterized by progressive external ophthalmoplegia, pigmentary retinopathy, and systemic manifestations including cardiac, endocrine, and neurological features. Early recognition remains challenging due to its heterogeneous and evolving phenotype.

Case Presentation: We describe a unique case of an 11-year-old male presenting with progressive ophthalmoplegia, bilateral ptosis, pigmentary retinopathy, sensorineural hearing loss, ataxia, and episodic hypersomnolence. His initial clinical course was marked by aplastic anemia with serious anemia and metabolic acidosis at the age of 9 months, after parvovirus infection. He was initially suspected of having sideroblastic anemia but improved with supportive transfusion. In the following years, he had worsening neurosensory impairment, motor clumsiness, and varying alertness. MRI demonstrated bilateral basal ganglia and brainstem changes. Genetic analysis showed a 7.7 kb mitochondrial DNA deletion covering several respiratory complex genes, in line with the diagnosis of Kearns-Sayre syndrome. Treatment with mitochondrial supplements and folinic acid was commenced on the basis of suspected secondary cerebral folate deficiency. The clinical presentation of the patient has been complicated by cyclical hypersomnolence, hypotonia, and progressive neuromuscular deterioration, for which evaluation was warranted through multidisciplinary assessment involving neurology, ophthalmology, audiology, cardiology, and genetics.

Conclusion: This report documents the extensive phenotypic variability of and diagnostic challenge in Kearns-Sayre syndrome, especially when preceded by hematologic presentation. Awareness of multisystem involvement and early time-of-day molecular diagnosis is necessary for effective management and genetic counseling. Folinic acid may provide symptomatic benefit in patients with suspected cerebral folate deficiency, although objective biomarkers were not available in this case.

Keywords

Kearns-Sayre syndrome, Chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia, Pigmentary retinopathy, Sensorineural hearing loss, Cyclical hypersomnolence

Introduction

Kearns Sayre syndrome (KSS) is a multisystem, mitochondrial cytopathy that is classically diagnosed by the combination of early-onset chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO), pigmentary retinopathy, and presentation within the first 20 years of life. Other associated features include cardiac conduction abnormalities, cerebellar ataxia, and raised cerebrospinal fluid protein, which makes the clinical picture very variable and complex [1].

Its incidence is estimated at between 1 and 3 per 100,000 persons, with initial reports of 1.6 per 100,000 in Finland. Etiologically, KSS results from extensive heteroplasmic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) deletions—usually several kilobases in length—that compromise oxidative phosphorylation [1,2]. More than 80% of patients exhibit such deletions in blood or muscle; the ubiquitous "4.9?kb" deletion is found in approximately one third of cases [3].

Despite well-established diagnostic criteria, early recognition remains difficult because the clinical and radiologic features often evolve gradually and overlap with other mitochondrial disorders.

Clinically, bilateral ptosis and ophthalmoplegia usually precede the disease, followed by pigmentary retinal changes (salt-and-pepper fundus), ataxia, sensorineural hearing loss, endocrinopathies, cardiac arrhythmias, and short stature [1]. Neurological features can involve weakness, CNS dysfunction, and lactic acidosis. Cardiac conduction abnormalities—most commonly heart block—are seen in about one-third of patients, with sudden cardiac death occurring in extreme cases [3]. Sensorineural deafness is "nigh universal" in the survivors into adolescence and adulthood, often necessitating cochlear implants but often also with residual deficits [3]. MRI can show basal ganglia, brainstem, or white matter signal abnormalities in keeping with mitochondrial encephalopathy.

While classically characterized by its neuro-ophthalmologic presentation, hematologic manifestations such as anemia, pancytopenia, or sideroblastic anemia may also occur in Kearns-Sayre syndrome (KSS) or other mitochondrial disorders like Pearson syndrome [4,5]. A seminal case series in 1999 reports aplastic anemia in KSS, illustrating the phenotypic similarity with Pearson syndrome and emphasizing the value of longitudinal assessment in anemia of early onset [5].

Genotype–phenotype correlation in KSS is governed by heteroplasmy and secondary proliferation of deleted mtDNA in tissues. Excessive deletion burden in blood frequently replicates the Pearson phenotype initially, while muscle tissue subsequently demonstrates elevated deletion load progressing to KSS. Heteroplasmy presents tissue-specificity and thereby emphasizes the need for examination of both blood and muscle in suspected cases [6].

Diagnosis is based on clinical phenotypes, corroborated by neuroimaging, increased lactate or CSF protein, and muscle histology showing ragged red fibers. Molecular proof of mtDNA deletions by blood or muscle study confirms the diagnosis. Treatment is still symptomatic and supportive without disease-modifying treatment as of yet. Therapies involve coenzyme?Q?? supplementation, folinic acid for cerebral folate deficiency, pacemaker insertion in case of heart block, and rehabilitative therapy [7,8].

This case is presented due to its rare combination of early aplastic anemia, progressive neuro-ophthalmologic deterioration, and cyclical hypersomnolence—features that expand the recognized clinical spectrum of KSS and may obscure the classical neuro-ophthalmological triad, delaying diagnosis.

Case Presentation

An 11-year-old boy of Romanian descent, living presently in the United States, was seen with a collection of progressive multisystemic symptoms with a view to a mitochondrial disorder. Fluctuating neurological symptoms, visual and auditory impairment, growth retardation, and episodes of hypersomnolence were features of his clinical course. The patient was the second child of parents who were healthy, non-consanguineous, and of Eastern European background, with no major family history for mitochondrial, neurological, or developmental illness. His elder sibling is said to be healthy and neurodevelopmentally normal.

A concise timeline of the patient’s illness is as follows:

• Age 6 years – First episode of severe anemia requiring transfusion.

• Age 7–8 years – Gradual onset bilateral sensorineural hearing loss.

• Age 9 years – Intermittent right-sided ptosis begins.

• Age 10 years – First episode of cyclical hypersomnolence lasting 2–3 days.

• Age 11 years – MRI abnormalities first noted, interpreted externally as possible glioma.

• Age 12 years – Worsening fatigue and recurrent hypersomnolence episodes.

• Age 13 years – Repeat MRI confirms stable symmetric leukodystrophy; genetic testing identifies large-scale mtDNA deletion.

The patient was born by elective cesarean section at 39 weeks of gestation in Romania. Birth parameters were within normal (weight 3.06 kg, length 49 cm, head circumference 33 cm). His neonatal course was significant for a systolic murmur, and interval normalization was diagnosed with follow-up imaging after echocardiography found a bicuspid aortic valve. The cardiac anomaly had been resolved by 9 months of age.

At about 9 months old, the patient was admitted to the hospital after undergoing a full-body immersion baptism. He became hypothermic, had severe metabolic acidosis (venous pH 5.5), and had severe anemia with a hemoglobin concentration of 3 g/dL. Aplastic anemia was diagnosed, and the patient needed two emergent blood transfusions. The anemia was thought to be idiopathic initially but retrospectively suspected to be secondary to parvovirus B19 infection, a recognized cause of transient aplastic crisis, particularly in genetically predisposed individuals [9]. Sideroblastic anemia was also a consideration at the time, but his hematologic parameters returned to normal without prolonged therapy. He did not need chelation or iron supplementation and had no repeated cytopenias.

The patient's neurodevelopment was said to have been normal for the first four years of life, although he was clumsier and less active physically compared to his peers. At age three, he had early-onset myopia, with corrective glasses being necessary. After a move by the family to Mexico, the parents noticed progressive hearing issues. An auditory brainstem response (ABR) test revealed profound bilateral sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL), but inconsistent behavioral responses to sound. He was fitted with hearing aids, which he refused to use, and speech continued relatively well preserved, but with altered voice quality.

At age six, the patient acquired bilateral ptosis and resisted upward gaze. A Mexican neurological workup suggested a mitochondrial disorder, with the suspicion especially for chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO). Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was originally described as abnormal with basal ganglia signal changes, but after it was reviewed by a second radiologist, it was read as normal, a finding due to interpretive variability that often occurs in early mitochondrial encephalopathy [10].

The apparent discrepancy between ‘abnormal’ and ‘normal’ MRI readings reflected interpretive differences rather than interval recovery. The initial MRI showed subtle T2 hyperintensities in the basal ganglia, but these were dismissed as within normal limits by a second radiologist, likely due to their mild and nonspecific appearance. On later re-evaluation by a neurometabolic team using higher-resolution sequences, these same regions clearly demonstrated symmetric metabolic-pattern involvement. Thus, all studies were retrospectively consistent, and the variation arose from differing radiologic thresholds rather than true radiologic change.

Neuroimaging findings

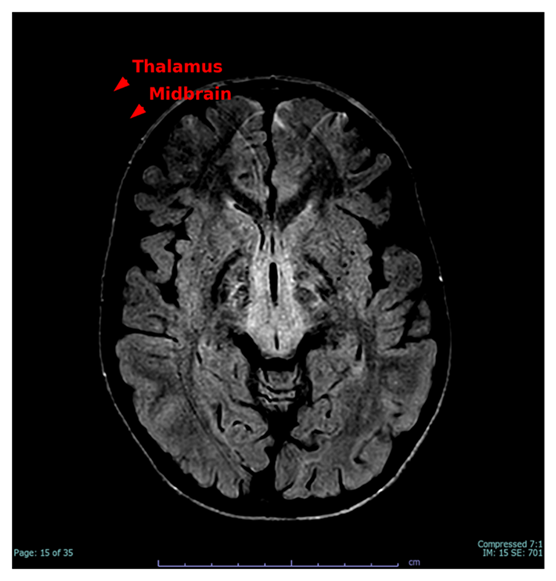

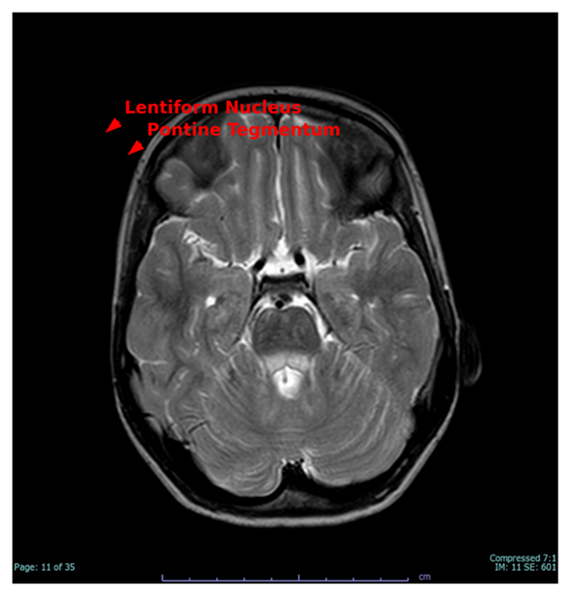

Neuroimaging was instrumental in establishing the diagnosis of mitochondrial encephalopathy. Axial T2-weighted MRI cuts, taken in 2018, showed multiple symmetrical hyperintensities of important brain structures. These, typical of mitochondrial cytopathies like Kearns-Sayre syndrome (KSS) or Leigh's disease, were at first underestimated secondary to varying radiologic interpretation. On re-evaluation by a neurometabolic team, the following were detected:

Figure 1 illustrates hyperintensities in the anteromedial thalamus and dorsal midbrain, indicative of classic mitochondrial tract involvement and consistent with the patient's vertical gaze palsy and central fatigue.

Figure 1. Axial T2-weighted MRI indicating bilateral T2 hyperintensities in the anteromedial thalamus and dorsal midbrain (red arrows), typical of mitochondrial pathology associated with Kearns-Sayre syndrome.

Figure 2 depicts symmetric engagement of the lentiform nuclei and pontine tegmentum, which are metabolically susceptible areas frequently involved in mitochondrial illnesses. Signal changes correlate with motor incoordination, extrapyramidal manifestations, and dysarthria noted in the patient.

Figure 2. T2-weighted axial MRI slice demonstrating bilateral engagement of the lentiform nuclei and pontine tegmentum (red arrows), characteristic features of mitochondrial encephalopathy.

Figure 3 demonstrates dorsal medulla signal alterations and volume loss in the perirolandic area, perhaps indicating a mixture of progressive mitochondrial degeneration and a distant perinatal hypoxic injury. These abnormalities correlate with the patient's dysautonomia, fine motor weakness, and evidence of pyramidal tract dysfunction.

These imaging characteristics, in combination with the clinical presentation and genetic verification of a 7.7 kb mitochondrial DNA deletion, confirm the diagnosis of Kearns-Sayre syndrome. The symmetrically distributed and metabolically active brain areas being

affected are hallmarks of mitochondrial cytopathies and aid in their distinction from demyelinating, neoplastic, or infectious processes.

Clinical suspicion of a mitochondrial disorder was maintained, and the patient was referred to a geneticist. Although muscle biopsy had been offered for diagnostic confirmation, it was deferred because of its invasive nature. Ophthalmologic examination instead found moderate bilateral ptosis, slow pupillary reactions, and diffuse pigmentary retinopathy, satisfying the cardinal clinical features of Kearns-Sayre syndrome (KSS) [11]. The combination of CPEO, pigmentary retinopathy, and onset of symptoms before 20 years of age led to a high level of clinical suspicion for KSS, especially with progressive systemic features.

Although muscle biopsy remains the historical gold standard for diagnosing mtDNA deletion disorders, it was not performed because genetic testing had already confirmed a pathogenic large-scale deletion. Current consensus guidelines state that when a causative mtDNA deletion is identified in blood, muscle biopsy adds little diagnostic value and exposes the patient to an unnecessary invasive procedure.

Genetic testing was finally conducted and validated the diagnosis. Mitochondrial DNA analysis revealed a heteroplasmic 7.7 kb deletion (m.7849_15601del7753) covering a number of vital mitochondrial genes such as MT-CO2, MT-ATP6, MT-ND4, and MT-CYB. The level of heteroplasmy was approximated at 55%, which is in line with a mitochondrial deletion syndrome spectrum, mostly KSS (GeneDx Laboratories, 2018). This genomic profile supported the clinical diagnosis and accounted for the progressive multi-organ compromise since mitochondrial deletions with these gene profiles affect respiratory chain function in different tissues [12]. A heteroplasmy level of 55% is considered moderately high and is compatible with symptomatic disease. In single large-scale mtDNA deletion syndromes, the threshold for clinical expression varies across tissues, with neurologic tissues typically showing manifestations once heteroplasmy surpasses 40–60%. The patient’s clinical profile corresponds well with this range.

Since the age of 9, the patient has had cyclic periods of hypersomnolence, which became one of the most troubling and limiting functions of his illness. Each attack took 2 to 3 weeks and was defined by excessive daytime sleepiness, severe fatigue, ataxia, tremor, and almost complete abolition of spontaneous movement. In between these episodes, the patient would sleep for over 20 hours a day and needed help with walking, eating, and bathing. His speech was slurred and balance was severely impaired, and he needed physical assistance to walk. These would then suddenly remit, with the patient recovering to near-baseline function for variable periods of time.

Differential diagnoses considered included non-convulsive seizures, hypothalamic dysfunction, sleep disorders such as Klein-Levin syndrome, medication effects, and episodic metabolic decompensation—each previously reported in mitochondrial cytopathies. Although EEG and sleep studies were pending, the pattern of reversible episodes with profound lethargy is compatible with intermittent central nervous system energy failure.

Three significant episodes were recorded within a four-month timeframe. The first episode occurred concurrently with relocation to a new house and was caused by environmental stress and irregular supplementation. The second episode occurred after routine vaccination and resulted in an emergency department visit where no acute pathology was found. The third episode occurred spontaneously and resulted in urgent outpatient assessment due to the severity of lethargy and motor impairment.

Neurological examination on the third episode of hypersomnolence showed extreme ptosis, ophthalmoplegia with the loss of vertical and horizontal eye movements, bradykinesia, ataxic wide-based gait, and dysarthria. Ophthalmologic examination established legal blindness in the left eye. The right eye had some central vision. Sensory responses were normal, but coordination tests like rapid alternating movements and mirror testing showed dyspraxia. There were no signs of seizures or autonomic instability. The patient was cooperative but needed repeated questioning to answer, showing profound central nervous system involvement.

|

Investigation |

Result |

Interpretation |

|

CBC during anemia episode |

Hb 3 g/dL |

Severe aplastic anemia |

|

ABR (2016) |

Absent bilateral response |

Sensorineural hearing loss |

|

Ophthalmology exam (2018) |

Bilateral ptosis, pigmentary retinopathy |

Meets KSS criteria |

|

Brain MRI (2018) |

Basal ganglia and brainstem abnormalities |

Suggestive of mitochondrial encephalopathy |

|

Mitochondrial DNA testing |

7.7 kb mtDNA deletion, heteroplasmic (55%) |

Confirms KSS diagnosis |

|

Lactate (2020) |

3.3 mmol/L (normal <2.2) |

Suggests impaired mitochondrial metabolism |

|

Cardiology (2020) |

Normal ECG, no heart block |

No cardiac conduction defect |

|

EEG |

Pending |

Rule out non-convulsive seizures |

|

CSF testing |

Not performed |

Deferred due to anesthesia risks |

During presentation, the patient's growth parameters were well below the first percentile (height 123 cm, weight 22.9 kg, BMI 15.11 kg/m²). He was alert mentally but exhibited cognitive slowing, most likely exacerbated by language change and potential mild intellectual disability. He was a student and received an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) with frequent academic evaluations.

The patient was treated symptomatically with mitochondrial cocktail therapy consisting of coenzyme Q10 (1200 mg/day), vitamin E, calcium-magnesium-D3, and omega-3 fatty acids. Folinic acid (leucovorin) 25 mg/day was recently started on the basis of reports of cerebral folate deficiency in KSS patients as a result of defective ATP-dependent transport of folate across the blood-brain barrier [13,14]. The dosage was titrated to 50 mg/day over two weeks. Even though CSF 5-MTHF levels were not quantified definitively because of risks of sedation, empiric therapy was considered appropriate. Differential causes of the cyclic hypersomnolence were non-convulsive seizures, sleep disorders (e.g., Klein-Levin syndrome), and mood disorders like mitochondrial-associated depression. An urgent routine EEG was prescribed to exclude electrical seizure activity. Cardiac causes were reconsidered as well, although previous studies were negative for arrhythmia or conduction defects.

The patient was also under consideration for inpatient admission to hasten investigations, such as sleep studies, prolonged EEG monitoring, and psychiatric assessment. Referral to a specialist in mitochondrial disorders was done, and the family sought expert advice at tertiary centers, including Cleveland Clinic and Johns Hopkins, actively.

In the face of progressive multisystem participation, the patient had a fairly good quality of life between attacks. The patient had resilience and ability to adapt, acquiring the ability to read in Spanish and starting English language learning. Socially, he remained well integrated with family and school friends, and there was active parental participation in his management.

Discussion

Kearns Sayre syndrome (KSS) is the prototype for the complexities of mitochondrial medicine, especially in children with multisystem overlap and changing clinical courses. Our case highlights this diagnostic challenge with a distinctive presentation of early onset aplastic anemia, progressive ophthalmoplegia, sensorineural hearing loss, pigmentary retinopathy, and cyclical hypersomnolence that ended in a genetically proven diagnosis of KSS.

Aplastic anemia and overlap with Pearson syndrome

Perhaps the most striking feature of this case is the ninth-month diagnosis of severe anemia that was first diagnosed as aplastic anemia and subsequently retrospectively reviewed as secondary to parvovirus B19 infection. Although parvovirus is a recognized cause of transient aplastic crises, especially in patients with pre-existing red cell pathology, its presence in the setting of an extensive mtDNA deletion suggests a more general pathophysiological mechanism [9].

Aplastic anemia in KSS is infrequent but has been reported in patients with overlapping features of Pearson marrow pancreas syndrome, which is also due to large-scale mtDNA deletions [5]. Leung et al. originally reported instances of KSS with hematologic presentation, speculating that such cases might be a phenotypic continuum but not discrete syndromes [5]. This is evidenced by longitudinal studies in patients who first present marrow dysfunction during infancy (Pearson phenotype), to progress to KSS in adolescence as hematology abnormalities improve [15].

As similarly emphasized in previous literature (Kanani, 2025), rare neurological conditions can present with misleading or fluctuating clinical and radiologic features that delay diagnosis, underscoring the need for broad differentials and repeated re-evaluation [26].

Phenotypic development is determined by tissue-specific heteroplasmy—the level of mutant mtDNA in a tissue—which can change over time as a result of differing replication dynamics and cell selection pressures [4]. The normalization of our patient's hematologic parameters following short-term therapy against classical Pearson syndrome. But the reported 7.7?kb mtDNA deletion spanning MT CO2, MT ATP6, and MT CYB gives a molecular explanation for early marrow suppression consistent with reports implicating large-scale mtDNA deletions in hematologic dysfunction through compromised oxidative phosphorylation [16].

Progressive external ophthalmoplegia and pigmentary retinopathy

The characteristic findings of KSS—chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO) and pigmentary retinopathy—were both present by the age of six in our patient, to further confirm the diagnosis. CPEO is usually the first and most striking sign of KSS, an expression of mitochondrial impairment in extraocular muscles, which are extremely reliant upon oxidative metabolism [2]. Histologically, such muscles are often found to have ragged red fibers.

The pigmentary retinopathy seen in KSS is distinct from classical retinitis pigmentosa. It is characterized by a "salt and pepper" fundus from atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium intermixed with pigment clumping—a description described by Paulus and Wenick [Paulus & Wenick, 2016; Retin Cases Brief Rep] and by Kozak et al. in their 2018 case series highlighting broad heterogeneity and necessity for serial ophthalmologic evaluation [17].

Sensorineural hearing loss and multisystem decline

Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) is a virtual universal finding in patients with KSS living into adolescence and adulthood [2]. It is caused by degeneration of cochlear hair cells and auditory neurons as a secondary result of impaired mitochondrial energy production. In our patient, bilateral SNHL was present at age five and prompted audiologic management. Hearing aids were poorly tolerated, a frequent problem in mitochondrial SNHL.

The sequential evolution of KSS is variable but usually includes neurological, cardiac, and endocrine systems. Our patient presented with cerebellar ataxia, motor incoordination, and developmental retardation—characteristics of mitochondrial encephalopathy [2].

Cyclical hypersomnolence: Extending the neurological spectrum

Cyclic hypersomnolence, as seen in this patient, is a rare and incapacitating presentation in mitochondrial illness, with sparse representation in current KSS literature. Nonetheless, an 11-year-old case was once reported with hypersomnia and bithalamic lesions as well as disturbances of sleep architecture [18]. Hypothalamic dysfunction has also been shown to be associated with MELAS and Leigh syndrome. CNS involvement including hypothalamic pathways was discussed by El Hattab and Scaglia in their 2016 review [19].

Sleep disorders in mitochondrial disease are underdiagnosed. Basu et al. (2020) described sleep-disordered breathing—particularly obstructive and central sleep apnea—as the most common type in mitochondrial disorders, highlighting the use of EEG and polysomnography in the differentiation of true hypersomnolence from seizure activity or encephalopathy?[20].

Genetic confirmation and heteroplasmy issues

Molecular diagnosis through detection of the 7.7?kb heteroplasmic mtDNA deletion yielded irrefutable proof of KSS. In about 90% of KSS cases, large scale mtDNA deletions are responsible; the common deletion can vary from 1.1 to 10?kb [2]. The clinically relevant heteroplasmy level of 55% in peripheral blood has been reported. Deletion load is tissue-specific and muscle tends to carry higher mutant loads than blood in older individuals; this concurs with reported tissue patterns of distribution in large mtDNA deletions?[21].

Management: Supportive interventions and folinic acid therapy

Today's standard treatment in KSS is symptomatic and supportive. Our patient was given a mitochondrial cocktail of coenzyme Q10, vitamins, and antioxidants—now extensively utilized despite the limited evidence [7]. CoQ10, especially when supplemented with creatine and alpha-lipoic acid, has shown mild but detectable clinical improvement in patients with mitochondrial DNA deletion syndromes (including KSS) and other mitochondrial cytopathies—e.g., decreased resting lactate, increased strength, and reduced oxidative stress markers in a randomized crossover trial [22].

Folinic acid in cerebral folate deficiency (CFD) and KSS

CFD has been excellently characterized in KSS, typically as a result of defective folate receptor-α transport across the blood–brain barrier. Ramaekers et al. (2013) discussed the syndrome and indicated that folinic (leucovorin) acid treatment may correct CSF 5-MTHF levels and create clinical improvements in patients with mitochondrial disease, including those affected by KSS [23]. Empiric therapy resulted in clinical improvement in our patient, attesting to its value in presumptive cases [24].

The worth of multidisciplinary and longitudinal care

KSS requires a multidisciplinary effort between specialties with its changing multisystemic presentation—neurology, ophthalmology, audiology, cardiology, endocrinology, and genetics. Consensus guidelines recommend annual CBCs and regular monitoring in at-risk patients for anemia or marrow suppression [25]. Cardiac monitoring is also needed because of the possibility of conduction abnormalities and sudden death. Educational and psychosocial support are also essential, since learning problems and mood disturbances ensue.

The patient’s initial hematologic crisis, evolving neurosensory deficits, and characteristic neuroimaging abnormalities can be unified under a single pathophysiologic mechanism: impaired oxidative phosphorylation from a large-scale mtDNA deletion. Tissues with high metabolic demand—bone marrow, extraocular muscles, cochlear hair cells, and deep gray matter nuclei—are disproportionately affected, resulting in early aplastic anemia, progressive ophthalmoplegia, sensorineural hearing loss, and episodic CNS decompensation. This integrative perspective helps reconcile the wide phenotypic variability observed in mtDNA deletion syndromes.

This case broadens the recognized clinical spectrum of KSS by identifying early onset aplastic anemia and cyclical hypersomnolence as progressive features of a massive mtDNA deletion. It emphasizes diagnostic difficulties due to tissue-specific heteroplasmy and progressive phenotypes. Early genetic testing, even in the absence of classical triads, is mandatory. The possible pathogenic role of folinic acid in cerebral folate deficiency deserves investigation. Future studies should emphasize biomarkers of disease progression and therapeutic responsiveness, preferably via multicenter longitudinal trials.

Overall, this case reinforces the importance of maintaining diagnostic vigilance when evaluating children with unexplained multisystem involvement. Early genetic testing, structured multidisciplinary follow-up, and awareness of atypical features—such as early marrow failure and cyclical hypersomnolence—can substantially improve diagnostic efficiency and guide long-term care.

Conclusion

This case highlights the remarkable phenotypic variability and diagnostic subtlety of Kearns-Sayre syndrome (KSS), especially when early hematologic disturbance obfuscates identification of the classic neuro-ophthalmologic findings. The initial infancy presentation of severe anemia and metabolic acidosis—followed years afterward by progressive ophthalmoplegia, sensorineural hearing loss, pigmentary retinopathy, and cyclical hypersomnolence—illustrates the dynamic course of large-scale mitochondrial DNA deletion disorders. The ultimate diagnosis of a heteroplasmic 7.7?kb mitochondrial DNA deletion highlights the importance of early genetic testing in facilitating diagnosis and management, particularly when invasive diagnostic tests such as muscle biopsy can be circumvented.

Our case highlights the value of longitudinal, multidisciplinary assessment, especially in children presenting with unexplained multisystem symptoms. Use of empirical folinic acid treatment on the basis of suspected cerebral folate deficiency is consistent with new evidence that it has a place in mitochondrial encephalopathies and presents a potential therapeutic option for symptomatic relief, even when definitive CSF studies are unavailable.

Clinically, our case reaffirms three points

1. Infantile marrow failure syndromes should raise suspicion of mitochondrial cytopathies, especially if later on systemic manifestations occur.

2. Cyclical hypersomnolence could be an underdiagnosed manifestation of central nervous system abnormality in KSS, deserving of increased attention and investigation by clinicians.

3. Genetic testing for mtDNA deletions allows for definitive diagnosis, guides family counseling, and allows for personalized therapeutic management.

Ultimately, this paper adds to the body of literature favoring a wider phenotypic range of KSS, such as transient aplastic anemia and episodic hypersomnolence. It also emphasizes the paramount importance of early diagnosis, thorough evaluation, and individualized management plans in mitochondrial illness. Multicenter research should consider investigating atypical symptom pathophysiology and reviewing long-term efficacy of folinic acid and other adjunctive treatments on neurological and functional status in the future and the reports aim to further characterize sleep-related manifestations in mtDNA deletion disorders, as they remain under-recognized and often misattributed.

References

2. Shemesh A, Margolin E. Kearns-Sayre Syndrome. [Updated 2023 Jul 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482341/.

3. Basu AP, Posner E, McFarland R, Turnbull DM. Kearns-Sayre Syndrome: Practice essentials, pathophysiology, epidemiology. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/950897.

4. DiMauro S, Schon EA. Mitochondrial disorders in the nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:91–123.

5. Leung TF, Hui J, Shoubridge E, Li CK, Chik KW, Shing MM, et al. Aplastic anaemia ETin association with Kearns-Sayre syndrome. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1999 Feb;22(1):86–7.

6. Larsson NG, Holme E, Kristiansson B, Oldfors A, Tulinius M. Progressive increase of the mutated mitochondrial DNA fraction in Kearns-Sayre syndrome. Pediatr Res. 1990 Aug;28(2):131–6.

7. Pfeffer G, Majamaa K, Turnbull DM, Thorburn D, Chinnery PF. Treatment for mitochondrial disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Apr 18;2012(4):CD004426.

8. Parikh S, Goldstein A, Koenig MK, Scaglia F, Enns GM, Saneto R, et al. Diagnosis and management of mitochondrial disease: a consensus statement from the Mitochondrial Medicine Society. Genet Med. 2015 Sep;17(9):689–701.

9. Young NS, Brown KE. Parvovirus B19. N Engl J Med. 2004 Feb 5;350(6):586–97.

10. Mancuso M, Orsucci D, Coppedè F, Nesti C, Choub A, Siciliano G. Diagnostic approach to mitochondrial disorders: the need for a reliable biomarker. Curr Mol Med. 2009 Dec;9(9):1095–107.

11. Khambatta S, Nguyen DL, Beckman TJ, Wittich CM. Kearns-Sayre syndrome: a case series of 35 adults and children. Int J Gen Med. 2014 Jul 3;7:325–32.

12. Gómez-Naranjo HJ, Espinosa-García E, Ardila S, Echeverri-Peña OY, Barrera-Avellaneda LA. Síndrome de Kearns Sayre: reporte de dos casos. Acta Neurológica Colombiana. 2017 Mar;33(1):32–6.

13. Ramaekers VT, Sequeira JM, Quadros EV. The basis for folinic acid treatment in neuro-psychiatric disorders. Biochimie. 2016 Jul;126:79–90.

14. Quijada-Fraile P, O'Callaghan M, Martín-Hernández E, Montero R, Garcia-Cazorla À, de Aragón AM, et al. Follow-up of folinic acid supplementation for patients with cerebral folate deficiency and Kearns-Sayre syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014 Dec 24;9:217.

15. Muraki K, Nishimura S, Goto Y, Nonaka I, Sakura N, Ueda K. The association between haematological manifestation and mtDNA deletions in Pearson syndrome. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1997 Sep;20(5):697–703.

16. Obara-Moszynska M, Maceluch J, Bobkowski W, Baszko A, Jaremba O, Krawczynski MR, et al. A novel mitochondrial DNA deletion in a patient with Kearns-Sayre syndrome: a late-onset of the fatal cardiac conduction deficit and cardiomyopathy accompanying long-term rGH treatment. BMC Pediatr. 2013 Feb 20;13:27.

17. Kozak I, Oystreck DT, Abu-Amero KK, Nowilaty SR, Alkhalidi H, Elkhamary SM, et al. NEW OBSERVATIONS REGARDING THE RETINOPATHY OF GENETICALLY CONFIRMED KEARNS-SAYRE SYNDROME. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2018 Fall;12(4):349–58.

18. Kotagal S, Archer CR, Walsh JK, Gomez C. Hypersomnia, bithalamic lesions, and altered sleep architecture in Kearns-Sayre syndrome. Neurology. 1985 Apr;35(4):574–7.

19. Reimann J, Kornblum C. Towards Central Nervous System Involvement in Adults with Hereditary Myopathies. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2020;7(4):367–93.

20. Brunetti V, Della Marca G, Servidei S, Primiano G. Sleep Disorders in Mitochondrial Diseases. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2021 May 5;21(7):30.

21. Houshmand M, Gardner A, Hällström T, Müntzing K, Oldfors A, Holme E. Different tissue distribution of a mitochondrial DNA duplication and the corresponding deletion in a patient with a mild mitochondrial encephalomyopathy: deletion in muscle, duplication in blood. Neuromuscul Disord. 2004 Mar;14(3):195–201.

22. Pfeffer G, Majamaa K, Turnbull DM, Thorburn D, Chinnery PF. Treatment for mitochondrial disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;2012(4):CD004426.

23. Rodriguez MC, MacDonald JR, Mahoney DJ, Parise G, Beal MF, Tarnopolsky MA. Beneficial effects of creatine, CoQ10, and lipoic acid in mitochondrial disorders. Muscle Nerve. 2007 Feb;35(2):235–42.

24. Ramaekers V, Sequeira JM, Quadros EV. Clinical recognition and aspects of the cerebral folate deficiency syndromes. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2013 Mar 1;51(3):497–511.

25. Ormazabal A, Casado M, Molero-Luis M, Montoya J, Rahman S, Aylett SB, et al. Can folic acid have a role in mitochondrial disorders? Drug Discov Today. 2015 Nov;20(11):1349–54.

26. Parikh S, Goldstein A, Karaa A, Koenig MK, Anselm I, Brunel-Guitton C, et al. Patient care standards for primary mitochondrial disease: a consensus statement from the Mitochondrial Medicine Society. Genet Med. 2017 Dec;19(12):10.1038/gim.2017.107.

27. Kanani J. Diagnostic challenges in hemangioblastoma: lessons from a rare case presentation. Egypt J Neurosurg. 2025 Aug 22;40(1):115.