Abstract

Unusual presentations of disease states that have been well characterized over the years is key to ensuring the safety of patients and decreasing the overall mortality and morbidity. Patients often present with variations on classical conditions and it is key that providers be able to recognize these variations. This case study presents a 70-year-old female with a complex past medical history with variation of the classical Hakim-Adams triad of Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus. In this case, the patient’s symptoms included an increasingly depressed mood with some suicidal ideation, a potentially difficult to parse out gait disturbance, and urinary incontinence that had to be elucidated through conscious efforts. The patient was ultimately referred to neurosurgery for ventricular-peritoneal shunt placement. This case study includes a differential diagnosis with rationale for the different potential diagnoses, an in-depth look at the pathophysiology of Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus, the major treatment strategies, and highlights some clinical pearls for trainees and practicing providers.

Keywords

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus, Ventricular-peritoneal shunt, Wet, Wacky, Wobbly, Depressed affect

Case Presentation

The patient is a 70-year-old, right-handed female with history of hypertension, type II diabetes mellitus, diabetic neuropathy of the lower extremities, hyperlipidemia, and major depressive disorder (MDD). During her previous primary care appointment, she complained of right arm numbness and neck pain which led the provider to order a Computerized Tomography (CT) head and cervical spine. The CT head demonstrated enlargement of the ventricles of the brain and effacement of the sulci, as noted by the radiologist, leading the team to further inquire about her symptoms.

She reported the following: fatigue (sleeping most of the day), and more importantly, worsening depression and consideration of overdosing on her prescribed opioid medication, resulting in death. She stated these symptoms were worse than her previous depressive episodes. The patient initially denied wanting help, but was amenable to a Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI). She denied further suicidal ideation, aside from the momentary lapse in judgement, and demonstrated future planning.

Upon further questioning, the patient divulged new onset urinary incontinence with nocturnal urinary urgency. She denied burning with urination and changes in the quality or coloration of the urine. She felt unable to fully empty her bladder when urinating. While the patient was multiparous, she reported that she had only developed these symptoms within the last few months. She admitted to altering her diet in order to lose weight by drinking more water; however, the urgency was still greater than expected.

The patient’s neurological deficits were measured using the standardized physical examination skills detailed in Bate’s guide to the physical exam [1]. On physical exam, the patient demonstrated 4/5 strength in the right arm and 5/5 strength in the left arm. The patient demonstrated global slowing of the reflexes and 1/2 pitting edema in the lower extremities. During gait assessment, the patient required the use of a walker and had balance difficulties, however, parsing these gait abnormalities from her diabetic neuropathy disability was difficult to impossible. The remainder of the physical examination was within normal limits.

Differential Diagnosis

Based on the patient’s psychiatric history, the most important diagnosis is MDD with suicidal ideation. However, with the constellation of other symptoms, this was deemed to be less likely than other diagnoses. Based on the constellation of symptoms and the length of time since the onset of the urinary incontinence, Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH) must be considered [2,3]. While the patient did not present with the classical magnetic gait or mental disturbances, this remains high on the differential due to the increased ventricular size and effacement of the sulci as noted by the radiologist.

Two disorders that can present either with depressed mood or with enlarged ventricles are Schizophrenia and Dementia. Schizophrenia is less plausible as the patient did not report any positive symptoms, whereas Dementia is also unlikely due to the lack of memory loss complaints from either the patient or the patient’s family. The patient is still independent and was not struggling with executive functioning, therefore, these two diagnoses are less likely.

The last two major considerations are a urinary tract infection (UTI) and worsening Diabetes Mellitus. While a UTI would cause increased urgency, this is less likely due to the chronic nature of the urgency and the lack of other symptoms such as suprapubic pain or burning with urination. Sadly, the classical symptoms of a UTI can often be missing in the elderly, therefore, as a result, a urinalysis must be run to rule out infection [4]. While worsening Diabetes Mellitus can present with urinary symptoms, with the patient having had stable Hemoglobin A1Cs for several months and without changes in her medications, this diagnosis is also less likely.

Treatment Strategy

Based on the patient’s history, physical examination, and imaging, it was determined that a ventricular-peritoneal shunt was necessary, and the patient was referred to neurosurgery. According to the current literature, the main treatment strategy for patients who experience NPH is the placement of a surgical ventriculoperitoneal or ventriculoatrial shunt [5]. This allows for the excess cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) to be re-entered back into normal bodily circulation [6]. After surgery, and with the help of physical and occupational therapies, a patient can see an improvement in quality of life, including a decrease in fall risks and a return to normal activities of daily living [7]. There are other surgical options; however, they remain under evaluation [8-10].

If the patient is against surgical intervention or there is a wait time until surgery, then medical management is necessary. The major medications for the medical management of NPH include carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and loop diuretics [11-14]. Acetazolamide works as a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor preventing the creation of CSF and Furosemide prevents reabsorption of fluid into the body at the level of the kidneys, decreasing the amount of fluid available for the creation of the CSF [11-14]. Due to differences in patient physiology, body habitus, and hydration status, the exact amount of fluid that is decreased is not clear, however, these medications have been shown to cause clinical improvement in patients [11-14]. The current dosing recommendation for Acetazolamide is 125–375 mg/day and for Furosemide it is 1 mg/kg/day [12,15,16]. Other medications have also been used to decrease the fluid build-up in the skull cavity to a lesser extent, but are still under study and not recommended for use at the time of writing [17]. Nevertheless, regardless of the method by which the fluid buildup decrease, these medications are not curative treatment, but instead a short-term solution until neurosurgical intervention [11-17].

Pathophysiology

The central nervous system (CNS) is completely enveloped by a solute-dense CSF which acts as a suspension liquid for the brain and provides hydro-mechanical protection [18]. CSF is produced by the choroid plexuses, a specialized brain epithelium that facilitates organic solute transport within the interstitial fluid of the blood-brain-barrier (BBB). The CSF travels within cerebral ventricles to descend along the spinal cord and then be reabsorbed by the arachnoid granulations within the subarachnoid space. Mean CSF volume is 150 ml, with the majority (125 ml) sequestered into the subarachnoid space and the remaining 25 ml within ventricular circulation [18]. CSF is renewed roughly four times daily, with other extracranial influences on circulation including the dynamic pressure of the venous system, posture, and respiration-dependent wave forms [19].

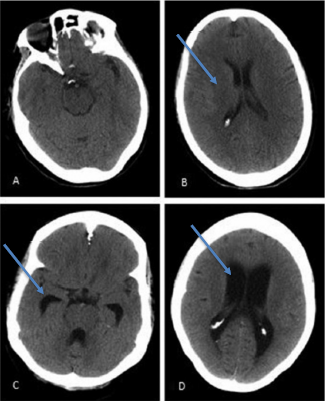

Dysfunction with secretion, circulation or reabsorption of CSF, and its subsequent build-up, could lead to presenting symptomatology of primary idiopathic NPH known as the Hakim-Adams triad [11]. The Hakim-Adams triad typically presents with gait abnormalities first. Nevertheless, like was seen in our patient case, gait can be difficult to gauge due to the patient’s medical history or ambulatory status. Gait abnormalities manifest as the CSF accumulation applied pressure to medial somatomotor pathways of the lower extremities [11,18,19]. Cognitive impairment soon manifests as the build-up of CSF impacts the anterior aspects of the brain via enlargement of the anterior horn of the lateral ventricle, leading to multiple mental impairments (Figure 1) [19]. As accumulation of CSF continues, the pressure on cerebral capillaries leads to ischemic damage, resulting in Dementia [11]. Other cognitive impairments include emotional lability, apathy, and mood dysregulation due to subcortical damage [6]. Finally, incontinence and nocturia set in as pressure upon thalamic projections accrue, completing the triad.

Figure 1: A and B: CT Scan of 71-year old female presenting with normal cognitive function with normal ventricular size whereas C and D are a CT scan of that of a 68-year old female with NPH with visible enlarged ventricles [14].

Discussion

The major clinical pearl was the lack of the classical triad. The patient demonstrated urinary incontinence and a decreased mood. However, she did not have the classical magnetic gait abnormalities. Whether this lack of gait abnormalities was a result of the diabetic neuropathy of the lower extremity, or the recency of the development of the NPH, is hard to distinguish. Had this patient only presented with her depressive symptoms and not received the CT as a result of another complaint, the potential for an NPH diagnosis would have been minimal, and she would have been solely treated with SSRIs for the depressive symptoms. While the patient was given a prescription of 10 mg of escitalopram, the standard starting dose for MDD, to be taken once a day by mouth [20], this was a temporary medication as the depression symptoms were most likely caused by the NPH [19]. Therefore, this case study is a lesson on the importance of having a wide differential and ensuring that all options are ruled out before jumping to conclusion.

The team wants to emphasize the importance of patient centered history taking. For example, as seen with our patient, she struggled with urinary incontinence. This was not something that she verbalized until asked. This exemplified a clear need to ask tailored questions to the patient’s condition and subsequent treatment, even if those questions seem to be too “normal” or of a taboo subject. According to nursing literature, assessment of urinary incontinence is a very private matter and often has cultural implications, therefore, it is up to the provider to acknowledge a patient frame of reference [21,22]. The team wants to highlight the imperative need for physicians to assess for individualized patient understanding of their condition and subsequent treatment.

Finally, special attention needs to be placed on suicidal ideation and its treatment. The patient demonstrated future planning with wanting to visit her granddaughters, as well as insight into her condition with statements of, “I gave away all the firearms in my home because I did not trust myself,” and was desirous for treatment. Had the patient demonstrated a lack of future planning or insight, this would have prompted emergent hospitalization.

Conclusion

This case study presented a variation of the classical Hakim-Adams triad. The patient demonstrated a depressed mood with some suicidal ideation, a difficult to parse out gait disturbance, and urinary incontinence that had to be elucidated through conscious efforts. The authors want to highlight the importance of patient history. Through careful questioning of the patient and ensuring that all systems have been checked during a clinic visit, the patient was saved from enduring the long-lasting effects of Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus. It is the team’s highest recommendation that practitioners ensure that they are taking a rich patient history to meet the patient’s needs.

References

2. Williams MA, Malm J. Diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Continuum: Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 2016 Apr;22(2 Dementia):579-599.

3. Andersson J, Rosell M, Kockum K, Lilja-Lund O, Söderström L, Laurell K. Prevalence of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: a prospective, population-based study. PloS One. 2019 May 29;14(5):e0217705.

4. Nicolle LE. Asymptomatic bacteriuria in the elderly. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 1997 Sep 1;11(3):647-62.

5. Andersson J, Rosell M, Kockum K, Lilja-Lund O, Söderström L, Laurell K. Prevalence of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: a prospective, population-based study. PloS One. 2019 May 29;14(5):e0217705.

6. Peterson KA, Mole TB, Keong NC, DeVito EE, Savulich G, Pickard JD, Sahakian BJ. Structural correlates of cognitive impairment in normal pressure hydrocephalus. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2019 Mar;139(3):305-12.

7. Modesto PC, Pinto FC. Home physical exercise program: analysis of the impact on the clinical evolution of patients with normal pressure hydrocephalus. Arquivos De Neuro-Psiquiatria. 2019 Dec;77(12):860-70.

8. Rendtorff R, Novak A, Tunn R. Normal pressure hydrocephalus as cause of urinary incontinence–a shunt for incontinence. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde. 2012 Dec;72(12):1130.

9. Tudor KI, Tudor M, McCleery J, Car J. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) for idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 Jul 29;(7):CD010033.

10. Balevi M. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy in normal pressure hydrocephalus and symptomatic long-standing overt ventriculomegaly. Asian Journal of Neurosurgery. 2017 Oct;12(4):605.

11. Gavrilov GV, Gaydar BV, Svistov DV, Korovin AE, Samarcev IN, Churilov LP, Tovpeko DV. Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (Hakim-Adams syndrome): clinical symptoms, diagnosis and treatment. Psychiatr Danub. 2019 Dec 1;31(Suppl 5):737-44.

12. Chang CC, Kuwana N, Ito S, Ikegami T. Response of cerebral blood flow and cerebrovascular reactivity to acetazolamide in patients with dementia and idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgical Focus. 1999 Oct 1;7(4): e10.

13. Del Bigio MR, Di Curzio DL. Nonsurgical therapy for hydrocephalus: a comprehensive and critical review. Fluids and Barriers of the CNS. 2015 Dec;13(1):1-20.

14. Nassar BR, Lippa CF. Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: a review for general practitioners. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine. 2016 Apr 19;2:2333721416643702.

15. Lorenzo AV, Hornig G, Zavala LM, Boss V, Welch K. Furosemide lowers intracranial pressure by inhibiting CSF production. Zeitschrift fur Kinderchirurgie: organ der Deutschen, der Schweizerischen und der Osterreichischen Gesellschaft fur Kinderchirurgie= Surgery in Infancy and Childhood. 1986 Dec 1; 41:10-2.

16. Gul F, Arslantas R, Kasapoglu US. Hydrocephaly: Medical Treatment. In: Gürer B, editor. Hydrocephalus: Water on the Brain. Intech Open Books. 2018. p. 77.

17. Chang CC, Kuwana N, Ito S, Ikegami T. Impairment of cerebrovascular reactivity to acetazolamide in patients with normal pressure hydrocephalus. Nuclear Medicine Communications. 2000 Feb 1;21(2):139-41.

18. Sakka L, Coll G, Chazal J. Anatomy and physiology of cerebrospinal fluid. European annals of otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Diseases. 2011 Dec 1;128(6):309-16.

19. Damulin IV, Oryshich NA. Normotensive hydrocephalia and dementia. Zhurnal nevrologii i psikhiatrii imeni SS Korsakova. 2005 Jan 1;105(1):78-82.

20. Wade AG, Crawford GM, Yellowlees A. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of escitalopram in doses up to 50 mg in Major Depressive Disorder (MDD): an open-label, pilot study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011 Dec;11(1):1-9.

21. Debus G, Kästner R. Psychosomatic aspects of urinary incontinence in women. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde. 2015 Feb;75(2):165-9.

22. Thompson DL. Urinary Elimination. In: Ostendorf WR, Editor. Fundamentals of Nursing. Elsevier. 2017. p. 1101-47.