Abstract

Solid Papillary Carcinoma (SPC) is a rare sub-type of breast cancer essentially observed in postmenopausal women, accounting for less than one percent of all breast malignancies. It usually presents as a palpable mass or bloody nipple discharge. We report a case of a forty one year old pre-menopausal female presenting with a long-standing lump in the retro-areolar region of the breast. Imaging and biopsy initially suggested invasive ductal carcinoma. The diagnosis of SPC was confirmed with histopathology post modified radical mastectomy. The patient received adjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy and is currently on Tamoxifen. At twelve months follow-up she remains disease free. This case highlights an uncommon presentation of SPC in a pre-menopausal woman and the importance of a panoptic approach in managing SPC with an emphasis on the need to optimize treatment protocols and improve patient outcomes.

Keywords

Solid papillary carcinoma, Rare breast tumor, Pre-menopausal breast cancer, Rare presentation

Introduction

Solid Papillary Carcinoma (SPC) is a rare malignancy primarily affecting elderly post-menopausal women, accounting for less than 1% of breast cancers. The average age of diagnosis is around 70 years. It originates from ductal epithelium and frequently involves the central region of breast. Nearly 95% cases are unilateral and often present with bloody nipple discharge or a palpable mass. Ultrasound with color doppler is the most sensitive imaging modality for breast papillary lesion [1].

Morphologically, SPC is composed of well-circumscribed nodules with fibrovascular cores. This appearance can sometimes mimic other conditions like florid ductal hyperplasia, lobular neoplasia, intra-cystic papillary carcinoma and low nuclear grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) [2].

SPC is considered carcinoma in situ for staging purposes unless definitive or suspected invasive foci are present [3]. While generally indolent, invasive variants may demonstrate aggressive behavior [4]. Upfront metastasis is rare, occurring in only 0.4% of cases, with approximately 90% of lesions being localized [5]. Complete surgical excision or mastectomy is the treatment of choice, but when invasive component is present, adjuvant modalities should be considered [6].

We present here a case of SPC breast highlighting its diagnostic ambiguity, misclassification potential and therapeutic consequences, particularly when invasive components are present. Further rarity is highlighted in terms of its presentation in a premenopausal patient.

Case

A 41-year-old female presented to the Surgery OPD with a painless palpable lump in the retro-areolar region of the right breast for the past 1.5 years. There was no nipple discharge or cyclical variation in lump size. She had no significant past medical history, and her menstrual, reproductive, and family history were all unremarkable. Physical examination revealed a 4 ? 4 cm firm, well-defined lump in the retro-areolar region, without overlying skin changes. There was a 2 ? 2 cm palpable right axillary lymph node. Sono-mammography revealed a solitary BIRADS category 5 solid-hypoechoic lesion in the retro-areolar region, measuring 4.8 ? 3.8 cm, along with an axillary lymph node measuring 2 ? 2 cm, in the anterior axillary fold, firm in consistency and mobile. Biopsy was suggestive of Invasive Ductal Carcinoma and immunohistochemistry (IHC) panel revealed negative immunostaining for Estrogen Receptor (ER), Progesterone Receptor (PR) and Her-2 neu. PET-CT confirmed localized disease.

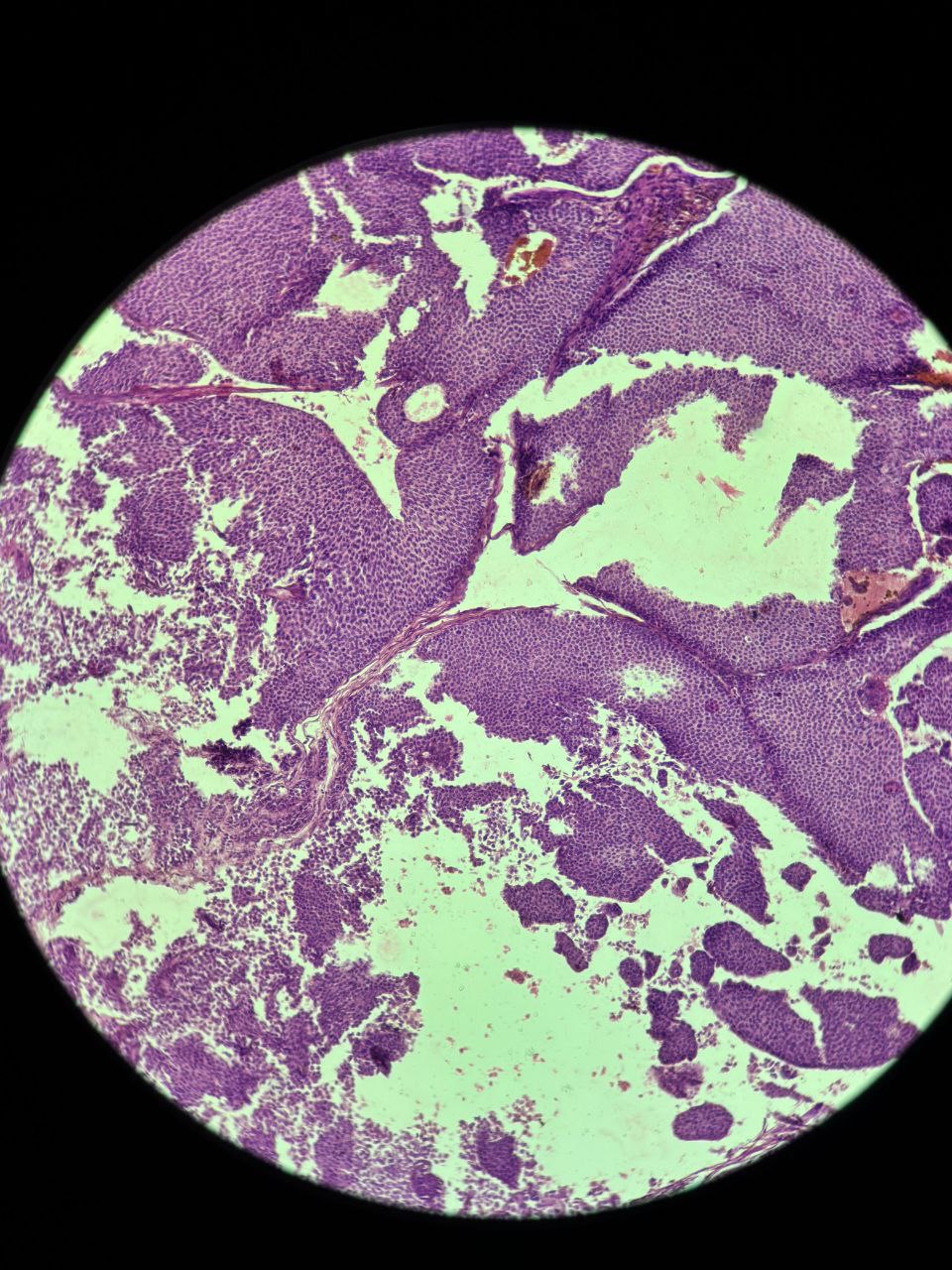

The patient underwent a Modified Radical Mastectomy with axillary dissection. Histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of Invasive Solid Papillary Carcinoma. The tumor was located in the retro-areolar region, measuring 7 ? 5 ? 2.5 cm. Microscopically, expansile nodules composed of a solid epithelial proliferation punctuated by delicate fibrovascular cores were noted (Figure 1). The epithelial proliferation had monomorphic, round to oval and plasmacytoid tumor cells with low to intermediate grade nuclear atypia (Figure 2). Infiltration into the surrounding adipose tissue was noted along with focal lymph vascular space invasion (LVSI). All surgical margins were free of tumor. One out of the twelve resected lymph nodes were positive for tumor cells. IHC revealed strong reactivity for cytokeratin (CK7), Epithelial Membrane Antigen (EMA) and Progesterone Receptor (PR), with negative immunostaining for chromogranin, synaptophysin, p63, CD 56, ER, and Her-2 neu.

After a multidisciplinary tumor board discussion, the patient received six cycles of adjuvant Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) and Carboplatin (AUC-5) every 3 weekly, followed by radiotherapy to the chest wall and axilla. The patient has been on Tamoxifen for the past eighteen months and is currently doing well.

Figure 1. Microscopic histopathological appearance showing expansile nodules composed of a solid epithelial proliferation, punctuated by delicate fibrovascular cores.

Figure 2. Histopathological features demonstrating an epithelial proliferation composed of monomorphic, round to oval and plasmacytoid tumor cells with low to intermediate–grade nuclear atypia.

Discussion

Papillary lesions of the breast represent a heterogenous spectrum, ranging from benign intraductal papillomas to malignant papillary carcinomas. In 1956, Maluf and Koerner [7] introduced the term "Solid Papillary Carcinoma" to describe a distinct entity of papillary breast lesions, most commonly found in elderly women. The prolonged 1.5-year duration in our case aligns with the indolent, minimally symptomatic nature of SPC, which is known to cause delayed presentation in similarly slow-growing papillary lesions

No specific etiological factors are known [5]. It typically originates from the ducts and is considered a variant of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) by some experts [4]. Average age of presentation is in the 7th decade of life; however, our case involved a 41 year old pre-menopausal woman, which makes it an unusual presentation and emphasizes the importance of considering SPC in younger patients as well.

Clinically, 95% of these tumors are unilateral, often presenting as a centrally located breast lump with nipple discharge [8]. In this case, patient presented with a retro-areolar mass but did not report nipple discharge. Mammography detects approximately 50% of SPC cases, whereas ultrasound is more sensitive and is the preferred imaging modality for these cases [1]. Ultrasonographic characteristics typically include a “frond-like” mass, either solid or complex cystic, within a dilated duct [9]. In this case, mammography demonstrated a suspicious BIRADS 5 lesion, but SPC was not suspected preoperatively, reflecting its well recognized tendency to mimic invasive ductal carcinoma on imaging.

Histopathologically, SPCs are characterized by multiple circumscribed nodules of monomorphic tumor cells arranged around fibrovascular cores [2,3]. Neuroendocrine differentiation demonstrated by chromogranin or synaptophysin positivity is reported in more than 50% of cases and is regarded as a diagnostic rather than a prognostic feature [3,8]. This feature is valuable for distinguishing SPC from other conditions, such as papilloma with florid ductal hyperplasia, which shows well-formed fibrovascular cores and high molecular weight cytokeratin, features absent in SPC. Interestingly, the tumor in our patient lacked neuroendocrine marker expression, which diverges from typical reported profile. Immunohistochemically, SPC usually demonstrate a luminal phenotype with ER, PR positivity and HER 2 negativity [8,10]. SPC typically shows a luminal (ER/PR-positive) profile; isolated PR positivity with ER loss is rare and creates uncertainty about endocrine responsiveness and its prognostic significance is not yet established. ER–/PR+ tumors often behave closer to ER–/PR– cancers and may carry a less favorable prognosis. Given the PR expression and invasive, node-positive disease, endocrine therapy was still offered, with longer follow-up needed to understand its true biological behavior [10].

Key to distinguishing SPC from ductal carcinoma in situ is the loss of the myoepithelial layer, which is identified by the absence of p63 staining on IHC, which further raided in diagnosis.

In terms of invasion, SPC is generally regarded as carcinoma in situ for staging purposes unless stromal invasion is evident [3]. There are two primary invasion patterns observed. The first pattern involves SPC associated with conventional invasive carcinoma which may consist of pure invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) or exhibit a mixed morphology that includes mucinous, neuroendocrine-like or less frequently, lobular and tubular subtypes.

The second pattern features predominant SPC with stromal invasion, often associated with desmoplastic stroma [8]. Our case demonstrated stromal invasion with focal LVSI.

Generally, SPC has a favorable prognosis, with limited lymph node metastasis typically seen only in cases with invasion [8]. Axillary lymph node is present in approximately 3–5% cases. Distant metastasis is rare, occurring in around 2–3% of patients and can be found without the involvement of axillary nodes [2]. Our case demonstrated one positive axillary lymph node. Important gaps still persist in the SPC literature, particularly regarding the inconsistent presence and prognostic value of neuroendocrine differentiation. Hormone-receptor variability further complicates biological interpretation.

The treatment protocols for SPC are still evolving and vary widely, ranging from breast-conserving surgery to mastectomy, guided primarily by the extent of the invasive component [6]. Adjuvant treatment is tailored according to stage and molecular classification, mainly in the invasive tumor. Given her tumor size (7 cm), invasive component, focal LVSI and nodal involvement and PR positive status, post operative chemotherapy, radiotherapy and endocrine therapy were planned for this patient. Since there are no concrete follow up guidelines, our case was followed up as any other breast cancer with clinical examination, mammography and endocrine therapy monitoring. Keeping in mind the rarity of the cancer, the patient was counselled for recurrent symptoms, stringent follow ups and compliance with endocrine therapy. At 18 months of follow up, our patient remains disease free, which aligns with published reports describing good outcomes even in invasive cases [5,6].

We are aware of the short follow-up duration, absence of genomic profiling and limitations inherent to single-case reports. Still, this case contributes to existing literature by highlighting three distinct features. First, the premenopausal age of onset which contrasts the typical postmenopausal demographic profile. Second, the tumor exhibited unusual IHC, being only PR positive and lacking neuroendocrine differentiation. Third, the presence of nodal metastasis and focal LVSI, although rare, underscores the malignant potential of invasive SPC. Together these features emphasize the complexity of SPC and the importance of meticulous clinical, radiological and histopathological assessment as the tumor can mimic various solid growth patterns.

Conclusion

SPC of the breast is a rare but well defined entity that generally carries a favorable prognosis, especially when diagnosed at an early stage. Its close morphological resemblance to several benign and malignant mimics underscores the need for a meticulous, multimodal diagnostic approach incorporating clinical assessment, imaging and effective treatment planning.

This case highlights the importance of maintaining diagnostic vigilance, especially in younger patients particularly in the presence of atypical IHC or invasive features, which may influence management decisions and long-term outcomes.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Arun Kumar Rathi - Head of Unit.

Dr. Savita Arora - General support.

Authors Contributions

Conceptualization: Wineeta Melgandi, Faiz Akram Ansari

Investigation: Tanshi Daljit, Saarthak Miglani

Writing – original draft: Tanshi Daljit, Saarthak Miglani

Writing – review & editing: Wineeta Melgandi, Faiz Akram Ansari, Tanshi Daljit, Saarthak Miglani

Statement

Manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors, and the requirements for authorship have been met and each author believes that the manuscript represents honest work.

References

2. Lin X, Matsumoto Y, Nakakimura T, Ono K, Umeoka S, Torii M, et al. Invasive solid papillary carcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation of the breast: a case report and literature review. Surg Case Rep. 2020 Jun 19;6(1):143.

3. Tan PH, Ellis I, Allison K, Brogi E, Fox SB, Lakhani S, et al. The 2019 World Health Organization classification of tumours of the breast. Histopathology. 2020 Aug;77(2):181–5.

4. Nassar H, Qureshi H, Adsay NV, Visscher D. Clinicopathologic analysis of solid papillary carcinoma of the breast and associated invasive carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006 Apr;30(4):501–7.

5. Mac Grogan G, Collins L, Lerwill M, Pakha E, Tan B. Breast tumors. WHO Classification of Tumors. (2019): 63–5.

6. Saremian J, Rosa M. Solid papillary carcinoma of the breast: a pathologically and clinically distinct breast tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012 Oct;136(10):1308–11.

7. Ahn S, Woo JW, Lee K, Park SY. HER2 status in breast cancer: changes in guidelines and complicating factors for interpretation. J Pathol Transl Med. 2020 Jan;54(1):34–44.

8. Jadhav T, Prasad SS, Guleria B, Tevatia MS, Guleria P. Solid papillary carcinoma of the breast. Autops Case Rep. 2022 Jan 13;12:e2021352.

9. You C, Peng W, Shen X, Zhi W, Yang W, Gu Y. Solid Papillary Carcinoma of the Breast: Magnetic Resonance Mammography, Digital Mammography, and Ultrasound Findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2018 Sep/Oct;42(5):771–5.

10. Bogina G, Munari E, Brunelli M, Bortesi L, Marconi M, Sommaggio M, et al. Neuroendocrine differentiation in breast carcinoma: clinicopathological features and outcome. Histopathology. 2016 Feb;68(3):422–32.