Abstract

The escalating prevalence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) Acinetobacter baumannii presents a formidable challenge to global healthcare, necessitating innovative therapeutic strategies. This review explores the critical role of clinical microbiology in the detection, surveillance, and management of MDR A. baumannii infections, underscoring the importance of accurate diagnostics and infection control. Concurrently, the pyrazole heterocyclic scaffold emerges as a promising molecular framework in the development of novel antibacterial agents, owing to its versatile chemical properties and demonstrated bioactivity against resistant strains. MDR A. baumannii has emerged as a major global health threat, with prevalence rates exceeding 60% in many hospital-acquired infections, thereby underscoring the urgent need for novel therapeutic approaches. This review provides a comprehensive analysis of recent advances in the development of pyrazole-based scaffolds, emphasizing structure-activity relationship (SAR) insights that rational design and fine-tuning of antibacterial potency and target selectivity. This integrated perspective highlights the synergy between clinical microbiological approaches and medicinal chemistry advancements, contributing to the design of more effective antimicrobial agents against the increasingly resistant and clinically significant pathogen A. baumannii.

Introduction

The global healthcare community is increasingly imperiled by the rise of bacterial pathogens exhibiting multidrug resistance (MDR), posing an existential challenge to conventional antimicrobial therapy. Central to this crisis are the ESKAPE pathogens-Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter-which are renowned for their ability to "escape" the effects of widely used antibiotics [1,2]. Of these, A. baumannii has emerged as one of the most formidable nosocomial threats, owing to its intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms that render standard treatment regimens increasingly ineffective. The modern era of clinical microbiology thus finds itself navigating a precarious post-antibiotic landscape in which even routine infections may escalate to life-threatening conditions [3,4].

From a microbiological point of view, Gram-negative pathogens of the ESKAPE group, particularly A. baumannii, present unprecedented therapeutic challenges due to their complex resistance mechanism. These bacteria possess efflux pump systems, a robust lipopolysaccharide-rich outer membrane, and a thin peptidoglycan layer (~5–10 nm), all of which confer considerable impermeability to antimicrobial agents [5,6]. In contrast, Gram-positive organisms, with a thicker peptidoglycan layer (~20–40 nm), allow for more facile antibiotic penetration and are therefore more susceptible to treatment [7,8].

Antimicrobial susceptibility data from the Meropenem Yearly Susceptibility Test Information Collection (MYSTIC) surveillance studies conducted across 15 major medical centers in North America highlighted the deteriorating efficacy of critical antibiotics against A. baumannii, with resistance rates exceeding 40% for agents such as aztreonam, ceftazidime, gentamicin, meropenem, and imipenem [9]. Historically, the discovery of penicillin heralded the advent of heterocyclic-based antibiotics, with β-lactams targeting DD-transpeptidase enzymes involved in bacterial cell wall biosynthesis [10]. Nevertheless, the widespread emergence of β-lactamase-producing strains, notably penicillinases, has rendered many of these agents obsolete [11,12]. As antimicrobial resistance continues to advance, the renewed clinical deployment of legacy antibiotics such as polymyxins and colistins-cationic lipopeptides originally introduced in the 1950s has become paramount interest [13]. However, their therapeutic relevance remains limited due to significant nephrotoxicity and the alarming rise of colistin-resistant A. baumannii strains, thereby underscoring the urgent need for novel antimicrobial scaffolds [14]. In this context, pyrazole-based molecular models have garnered substantial attention as promising candidates for next-generation antibacterial agents. The pyrazole moiety is a privileged heterocyclic motif widely used in medicinal, synthetic, and bioorganic chemistry, owing to its tunable electronic properties, chemical versatility, and usual presence in bioactive compounds [15-18]. Numerous synthetic and natural products comprising pyrazole scaffolds (Figure 1) exhibit a broad spectrum of biological activity, including potent antibacterial effects.

Figure 1. Structurally important pyrazole-derived therapeutic agents.

Augmenting pharmacological development, clinical microbiology plays an indispensable role in the containment of MDR A. baumannii within hospital settings. The implementation of proactive surveillance measures to detect colonization by MDR or pandrug-resistant (PDR) strains can inform timely infection control responses. Nevertheless, current methodologies for detecting colonization lack sensitivity and standardization. Initial studies indicate that cultures obtained from sites such as the anterior nares, oropharynx, skin, and rectum-when grown on MacConkey agar enriched with ceftazidime (8 µg/mL) and amphotericin B (2 µg/mL)-yield detection rates as low as 25% per site [19]. These limitations emphasize the necessity for more robust diagnostic tools, such as molecular diagnostics, polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based screening, and multiplexed pathogen panels, to accurately identify colonized individuals and prevent nosocomial dissemination [11,14,15–17]. Furthermore, the impact of such surveillance on clinical outcomes including infection incidence and transmission dynamics remains insufficiently characterized. Future investigations must not only refine the sensitivity and specificity of detection platforms but also rigorously evaluate their integration into infection control protocols and antimicrobial stewardship frameworks. In summary, an integrated strategy combining structure-activity relationship (SAR)-driven development of pyrazole therapeutics with enhanced clinical microbiology surveillance is critical to confronting the escalating threat posed by MDR A. baumannii. Through interdisciplinary alliance, the prospects of restoring effective antibacterial therapy and mitigating the global spread of this resilient pathogen can be meaningfully advanced. While numerous studies have demonstrated the promising pharmacological efficacy of pyrazole-based compounds, notably in antimicrobial and anticancer contexts, their pharmacokinetic properties and toxicological profiles remain underexplored. This gap limits the ability to assess their clinical viability. Comprehensive evaluation of absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion (ADME), and safety are essential for advancing these compounds from preclinical findings to therapeutic application. Future studies should prioritize these aspects to better define the translational potential of pyrazole derivatives. This review aims to underscore the pivotal role of clinical microbiology insights with detailed structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies in advancing pyrazole-based therapeutic targeting multidrug-resistant A. baumannii. By elucidating these aspects, the review seeks to advance understanding and foster innovative strategies to combat this highly resilient pathogen, ultimately contributing to the development of more effective and precise antimicrobial interventions.

Chemically Diversified Pyrazole Scaffolds as Promising Therapeutics for Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

Thiophene-functionalized pyrazolo [1,5-a]pyrimidines (compounds 1; Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC): 31.25–250μg/mL; Figure 2) demonstrated limited to moderate bactericidal activity against Acinetobacter baumannii. SAR elucidation revealed that halogenation of the phenyl ring significantly augmented activity, whereas aryl substitution at the C-3 amino position exerted negligible influence [20]. Replacing the pyrazole ring with 1,2,4- or 1,2,3-triazoles did not improve antibacterial efficacy [21,22]. Enhanced antibacterial performance was further observed with aminophenyl and arylazo substituents due to increase in the electron density and more solubility. Most derivatives displayed minimal activity against P. aeruginosa and Gram-positive strains, except 1a (Figure 5), which retained efficacy against S. aureus and S. mutans. The substitution of electron-withdrawing groups, significantly enhanced potency, outperforming standard antibiotics in E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and A. baumannii.

In 2022, Sannio et al [23]. investigated pyrazole carboxamides, previously reported by Mugnaini et al [24], for antibacterial activity. While one compound showed pronounced activity against Gram-positive strains, derivatives 2 and 3 in Figure 2 retained activity against Gram-negative bacteria, excluding P. aeruginosa. Compound 2 (Figure 2) had a narrower spectrum with enhanced cytotoxicity toward eukaryotic membranes, whereas 3 (Figure 2) exhibited synergism with colistin and potentiated bactericidal activity against colistin-resistant A. baumannii, most likely due to membrane-disrupting interactions.

Figure 2. Di-, tri, and tetra-substituted pyrazole derivatives (MIC: 1.56–250μg/mL) as antibacterials against A. baumannii.

Pyrazole-imine hybrids (4, Figure 2) exhibited the notable bacteriostatic activity (MIC: 1.56–12.5μg/mL), with halogenated aromatics outperforming other derivatives. Replacing trifluoromethyl groups with carboxylic acids significantly improved potency (MIC: 0.78–3.12μg/mL). A pyrazole–penicillin hybrid restored imipenem efficacy against carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii strains [25,26].

Pyrazole hydrazones (MIC 4μg/mL) exhibited strong anti-A. baumannii properties without cytotoxicity. Further optimization led to compound 5 (Figure 3, MIC: 0.73μg/mL), with analogs also targeting S. aureus and B. subtilis [27]. Structural modifications such as fluorine-to-carboxylic acid preserved the antibacterial activity, while coumarin substitutions (6, Figure 3) attenuated activity [28].

Figure 3. Hydrazone-functionalized pyrazole derivatives (5 and 6; MIC: 0.73–6.25μg/mL) as potential anti-A. baumannii agents and diversified pyrazoles (7 and 8; MIC: 0.31–3.125μg/mL) as antibacterial agents.

Host-directed therapy has also shown promise. Inhibition of the small GTPase ARF6-via genetic ablation or pharmacological blockade-improved survival in murine A. baumannii pneumonia models. Small-molecule inhibitors (7, Figure 3) restored endothelial barrier integrity by disrupting LPS-induced TLR4/MyD88/ARF6 signaling, offering a novel adjunctive strategy against resistant Gram-negative infections [29,30].

In 2020, Mugnaini et al [24]. evaluated various compounds for antibacterial efficiency, identifying only 54% compounds with measurable inhibitor activity (≥4 mm inhibition zone), particularly against Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens [31] such as K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii. Only a few compounds exhibited potent inhibition (≥10 mm), with ethyl ester derivatives demonstrating superior activity. Whitt et al. [32,33] synthesized a library of fluorinated pyrazole-hydrazones (8a–8d, Figure 3), leveraging the metabolic stability of C–F bonds. These analogs were screened against seven Gram-negative strains. While most exhibited limited spectrum, derivatives bearing 3- or 4-fluorophenyl moieties showed modest activity against A. baumannii, with the most active compound achieving a MIC of 3.125μg/mL [34].

In 2022, Ali Mohamed and Ammar [35] synthesized pyrazole derivatives containing thiazol-4-one/thiophene scaffolds, demonstrating potent antibacterial activity with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) as low as 0.78µg/mL. These compounds exhibited low hemolytic activity and significant inhibition of DNA gyrase and dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), with favorable docking scores indicating strong binding affinities. Earlier in 2021, Ahmad et al. [36]. developed pyrazole benzamide derivatives, notably compound 12b (Figure 4), which displayed superior activity against NDM-1-positive A. baumannii. Molecular docking studies revealed stable binding conformations, supporting the compounds' potential as therapeutic agents. In the past, Whitt et al. [32,33]. synthesized pyrazole hydrazone derivatives, identifying compounds 8 (Figure 3) with MICs ranging from 3.125 to 6.25µg/mL against A. baumannii. These derivatives exhibited selective activity against Gram-negative bacteria, with limited efficacy against other strains.s.

Alfei et al. [37]. used pyrazole derivative CB1H into cationic copolymer matrices resulted in CB1H-copolymer nanoparticles, which exhibited potent antibacterial activity against various clinical isolates, including both Gram-positive and Gram-negative MDR strains. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) ranged from 0.6 to 4.M, demonstrating up to a 16.4-fold improvement over unmodified CB1H. Time-kill assays confirmed rapid bactericidal effects, with over a 4-log reduction in bacterial counts within 4 hours for Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, and complete eradication of Pseudomonas aeruginosa within 1 hour. Cytotoxicity evaluations on human keratinocyte cells (HaCaT) indicated selectivity indices up to 2.4, suggesting favorable therapeutic profiles [38].

The synthesis of CR232 (13, Figure 4), a pyrazole derivative with limited solubility, into dendrimer-based G5K nanoparticles (NPs) addressed solubility challenges and enhanced antimicrobial potency. CR232-G5K NPs demonstrated MICs ranging from 0.36 to 2.89µM against various MDR strains, including colistin-resistant P. aeruginosa and carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae. Time-kill studies revealed rapid bactericidal activity, with no significant bacterial regrowth after 24 hours. Cytotoxicity assessments on HaCaT cells indicated selectivity indices between 34.5 and 276.4, underscoring the safety and efficacy of the formulation [37,39].

Figure 4. Heterocyclic conjugated pyrazoles (9-11; MIC: 0.97–12.5μg/mL), pyrazole benzamide derivatives (12; MIC: 0.73–6.25μg/mL), and other pyrazoles (13-CR232; MIC: 0.6–4.8μg/mL and 14-CB1H; MIC: 0.72–1.44μg/mL) as anti-A. baumannii agent

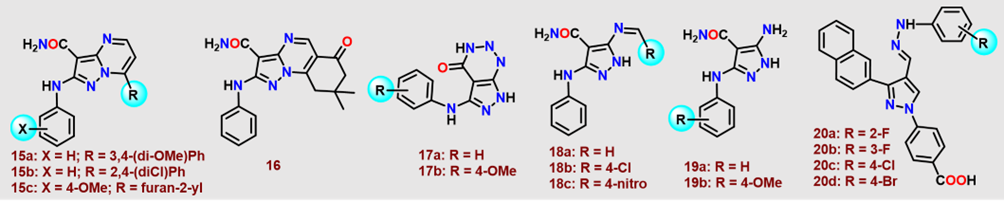

In 2018, Hassan et al. [40]. evaluated the in vitro antimicrobial efficacy of fused pyrazoles (15–17, Figure 5), Schiff bases (18, Figure 5), and 5-aminopyrazoles (19, Figure 5) against multidrug-resistant bacterial strains (MDRB) (Figure 5). Compounds 15a and Schiff base 18c in Figure 5 exhibited pronounced potency against S. aureus (MIC: 7.81μg/mL). For S. epidermidis, 15b (1.95μg/mL), 17a (0.97μg/mL), and 18c (3.91μg/mL) demonstrated significant activity (Figure 5). Compounds 15b, 16, and 17a,b (Figure 5) (3.91μg/mL) displayed unprecedented efficacy against E. faecalis. Compounds 19a and 19b (Figure 5) demonstrated potent inhibitory activity against A. baumannii, with MIC values of 3.91μg/mL. In contrast, compounds 15a, 15c, 16, and 18 (Figure 5) exhibited moderate antibacterial activity, each with MIC values of 7.81μg/mL. Against E. cloacae, compounds 16 (1.95μg/mL), 17a (0.48μg/mL), and 18a (3.91μg/mL) (Figure 5) showed significant efficacy. Additionally, compounds 17a and 17b displayed moderate inhibition of E. coli, each with an MIC of 7.81μg/mL. Subsequent screening of pyrazole derivatives (20, Figure 5) revealed the primarily bacteriostatic effects against A. baumannii. Fluoro-substituted congeners (20a,b, Figure 5) uniformly inhibited all tested strains (MIC 6.25μg/mL), whereas chloro-substituted (20c, Figure 5) exhibited enhanced potency against Ab06 (3.125μg/mL). The 4-bromophenyl analog (20e, Figure 5) demonstrated superior inhibition (MIC 1.56μg/mL) against Ab06, with other analogs exhibiting attenuated or moderate efficacy.

Figure 5. Polysubstituted pyrazole derivatives (15-20; MIC: 1.56–7.81μg/mL) as antibacterial agents against A. baumannii.

Recently, Braun-Cornejo et al. [41]. synthesized a library of eNTRy-rule-compliant derivatives by introducing ionizable nitrogen moieties into a planar, rigid pyrazole-amide scaffold (21–27, Figure 6), thereby enhancing Gram-negative permeability.

Various derivatives (21–27, Figure 6) displayed moderate to robust antibacterial activity against A. baumannii (≥45% inhibition at 50 μM; MIC95 <25μM), with 25 and 27 in Figure 6 achieving MIC95 values of 22 and 17μM, respectively. Their analogous potency against E. coli K12 suggests conserved bioavailability and target engagement. Abu-Zaied et al [42]. also used acrylamide-pyrazole conjugates, compound (28a, Figure 6) which exhibited an inhibition zone of 18 ± 1 mm against A. baumannii, closely rivaled by (28b, Figure 6) (21±1 mm), relative to Tigecycline (23±0.4 mm).

Figure 6. Polysubstituted pyrazoles functionalized with amines/N-alkylated guanidines (21-27) and conjugated acrylamide pyrazoles (28): A promising candidate against A. baumannii infections.

Pyrazole-based scaffolds have emerged as a promising chemotype in the development of novel antibacterial agents, particularly against multidrug-resistant A. baumannii. A comprehensive evaluation of diverse pyrazole derivatives has revealed significant antibacterial potential, driven by specific structural modifications that enhance activity and selectivity. The variations in the pyrazole scaffold-such as halogen substitution, heterocyclic fusion, and hybridization with other pharmacophores-play a critical role in modulating antimicrobial efficacy as shown in Table 1.

|

Compound No. |

Modification/Type |

MIC (µg/mL) |

Observed Effect |

|

1 |

Thiophene–pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines |

31.25–250 |

Halogenated phenyl ring enhanced activity; some equal to tigecycline |

|

2 |

Pyrazole carboxamide analog |

Moderate |

Narrow spectrum; enhanced membrane damage |

|

3 |

Pyrazole carboxamide analog |

Moderate |

Synergy with colistin; activity against colistin-resistant strains |

|

4 |

Pyrazole-imine hybrids with halogenated aryl rings |

1.56–6.25 |

Comparable to colistin; disrupt membrane integrity |

|

5 |

Pyrazole hydrazones |

0.73–4 |

Active against A. baumannii; non-toxic to HEK cells |

|

6 |

Fluorinated/coumarin-modified pyrazoles |

0.78–6.25 |

Activity depends on substitution; coumarins reduced efficacy |

|

7 |

ARF6 inhibitors (vascular targeting) |

0.31 |

Effective in vivo by restoring host vasculature during infection |

|

8 |

Fluorinated pyrazole hydrazones |

3.125 |

Mild to moderate activity |

|

9–11 |

Thiazol-4-one/thiophene hybrids |

0.97–12.5 |

Dual enzyme inhibition (DNA gyrase, DHFR); biofilm inhibition |

|

12 |

Benzamide derivatives (via Suzuki coupling) |

0.73–6.25 |

12b most active; docking confirmed binding to NDM-1 enzyme |

|

13 (CB1H) |

Nanoparticle-encapsulated pyrazole |

0.6–4.8 |

Strong effect vs. MDR strains; enhanced selectivity indices (SIs) |

|

14 (CR232) |

Dendrimer-based pyrazole formulation |

0.72–1.44 |

Effective vs. colistin-resistant strains; high SI and fast bactericidal effect |

|

15 |

Fused pyrazole derivative |

3.91–7.81 |

Moderate to Good efficacy vs. A. baumannii |

|

16 |

Schiff base pyrazole |

7.81 |

Good activity vs. A. baumannii, E. faecalis |

|

17 |

5-Aminopyrazole |

3.91–7.81 |

Strong activity against S. epidermidis, E. cloacae, and A. baumannii |

|

18 |

Schiff bases |

7.81 |

Moderate effect vs. A. baumannii |

|

19 |

5-Aminopyrazoles |

3.91 |

Strong activity; best among Schiff base and 5-aminopyrazoles |

|

20 |

Fluoro-/chloro-/bromo-substituted pyrazoles |

1.56–6.25 |

Specific strains inhibited; 20d most potent (1.56 µg/mL) |

|

21–27 |

Pyrazole-amides modified to follow eNTRy rules |

17–22 μM (MIC95) |

25 and 27: Best hits; good activity in A. baumannii and E. coli |

|

28a |

Acrylamide–pyrazole conjugate |

Zone: 18±1 mm |

Moderate inhibition; tested by zone of inhibition assay |

|

28b |

Acrylamide–pyrazole conjugate |

Zone: 21±1 mm |

Stronger than 28a; comparable to tigecycline (23±0.4 mm) |

These modifications not only improve membrane permeability but also reduce recognition by bacterial efflux pumps and enhance intracellular target engagement. Consequently, pyrazole-based compounds can potentially overcome resistance mechanisms such as porin loss and efflux pump activity, which are frequently observed in MDR A. baumannii. Beyond the conventional antibacterial action, the strategic design of pyrazole derivatives can also exploit vulnerabilities in bacterial virulence mechanisms. Key virulence factors in A. baumannii, such as outer membrane proteins (OMPs) like OmpA and CarO, contribute significantly to host cell adhesion, immune evasion, and antibiotic resistance. Inhibiting these targets with small molecules may impair bacterial survival and enhance susceptibility to existing antibiotics. Similarly, the quorum sensing (QS) system-which governs biofilm formation, surface motility, and expression of virulence genes-represents another attractive target. Pyrazole scaffolds, owing to their structural adaptability and physicochemical versatility, are particularly well-suited for optimization against such non-traditional targets. Incorporating SAR insights not only from bactericidal activity but also from anti-virulence effects may result next-generation therapeutics that disarm the pathogen without exerting direct selective pressure, thus offering a complementary strategy to traditional antibiotics in the fight against MDR A. baumannii.

However, despite promising in vitro efficacy, the translation of pyrazole-based compounds into viable clinical candidates requires a series of rigorous steps. The development process typically begins with SAR-driven lead optimization to improve potency, selectivity, and safety profiles. In silico ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) predictions are employed to identify pharmacologically viable compounds. Subsequently, in vivo studies in relevant infection models assess pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution, therapeutic efficacy, and systemic toxicity. Given the challenges associated with solubility and bioavailability, advanced drug delivery strategies-such as nanoparticle encapsulation, liposomal formulations, or prodrug design-are often necessary to enhance therapeutic potential.

Prior to entering clinical trials, candidate compounds must pass regulatory preclinical safety assessments, including genotoxicity and organ-specific toxicity studies under good laboratory practice conditions. Those meeting safety and efficacy benchmarks can proceed through the clinical development pipeline, beginning with Phase I trials (focused on safety and tolerability in healthy volunteers), followed by Phase II (dose optimization and preliminary efficacy in patients), and Phase III (large-scale validation of clinical benefit). For A. baumannii infections-especially in critically ill patients-clinical trials must also consider infection complexity, host immune status, and the potential for resistance evolution. In many cases, combination therapy approaches may be evaluated to enhance efficacy and reduce the likelihood of resistance development.

Clinical Significance and Impact of Acinetobacter Baumannii Infections

Acinetobacter baumannii exhibits a notorious propensity to colonize and infect critically ill patients, who inherently possess poor prognoses irrespective of secondary infections, complicating the precise elucidation of its clinical impact and fueling persistent controversy within the literature [43–45]. Pronounced methodological heterogeneity across studies further obfuscates definitive conclusions [19]. Although most investigations employ matched cohort or case-control frameworks, heterogeneity in case definitions and control group criteria is pervasive. Case definitions variably encompass patients with A. baumannii infection alone, combined infection and colonization, single- versus multi-site infections and inclusion of polymicrobial infections. Controls range from uninfected and uncolonized individuals, colonized but uninfected subjects, infection with susceptible isolates only, to infection with any pathogen regardless of specificity. Additionally, inconsistency in severity-of-illness adjustments, comorbidity matching, and species identification methods further undermines outcome reliability. In recent studies, the molecular diagnostics are increasingly relevant for tackling multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and directly support the discovery of new agents such as pyrazole derivatives. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has been used to map hospital transmission events, uncover novel resistance genes, and characterize colistin-resistant strains, thereby providing critical insights into resistance mechanisms [46]. In parallel, rapid PCR-based diagnostics enable same-day identification of pathogens and resistance determinants, facilitating faster clinical decision-making process [47]. The integration of these tools with medicinal chemistry enhances drug discovery by ensuring that new scaffolds, including pyrazoles, are evaluated against genetically defined, clinically relevant isolates. Because pyrazoles can be readily modified to tune their antibacterial activity, aligning SAR data with resistance profiles identified by WGS and PCR accelerates rational design and increases the translational potential of these compounds.

A notable CDC analysis incorporating rigorous confounder adjustment and strict case-control criteria reported no statistically significant increase in mortality among patients with multidrug-resistant A. baumannii compared to uninfected controls (OR 6.6; 95% CI: 0.4–108.3), though prolonged hospital and ICU stays were observed [45]. These findings are consistent with select studies [48,49] but contrast with others linking multidrug or carbapenem resistance to worse outcomes [50–53]. Complementary analyses further suggest that A. baumannii bacteremia may confer higher mortality risk than bacteremia due to other Gram-negative pathogens, including Klebsiella pneumonia [54,55]. Kaplan–Meier analyses have also shown increased mortality in cases of multidrug-resistant A. baumannii compared to multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa [56]. However, these studies often lack standardized severity scoring systems (e.g., APACHE, McCabe, Charlson indices), which may account for conflicting results across the literature.

Geographic clustering of studies raises the possibility that strain-specific virulence contributes to the observed variability in clinical outcomes, a hypothesis supported by disproportionately severe presentations of community-acquired A. baumannii infections in tropical regions [57]. The role of empirical antimicrobial therapy remains similarly contentious: while some studies identify inappropriate initial therapy as an independent predictor of mortality [58,59], others do not [60,61], likely reflecting sample size limitations and insufficient statistical power.

Comparative data between A. baumannii and non-baumannii Acinetobacter species are limited. A Korean cohort study observed no significant mortality difference after adjustment, although A. baumannii was associated with prolonged hospitalization [62]. Nonetheless, limitations in species identification undermine confidence in such findings. Mounting genomic evidence challenges the long-held view of A. baumannii as a low-virulence organism, revealing ongoing acquisition of multidrug resistance and putative virulence factors [63]. These evolutionary adaptations underscore the emergence of a more formidable pathogen with escalating implications for therapeutic efficacy and clinical management.

Host-pathogen Dynamics Involving Acinetobacter

Relative to other Gram-negative pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the host-pathogen dynamics of A. baumannii remain scarce. Recent whole-genome sequencing has revealed an extensive arsenal of antibiotic resistance genes coupled with numerous pathogenicity islands within A. baumannii [63]. Intriguingly, many resistance determinants targeting antibiotics, heavy metals, and antiseptics appear horizontally acquired from highly virulent bacteria like Pseudomonas, Salmonella, and Escherichia coli, suggesting a parallel potential for the horizontal transfer of virulence factors [63].

Random mutagenesis studies in A. baumannii American Type Culture Collection (ATCC-17978) identified mutants with attenuated virulence localized to six pathogenicity islands, encoding transcriptional regulators, multidrug efflux pumps, and urease, although these phenotypes were characterized only in non-mammalian models [64]. Comparative genomics with the non-pathogenic A. baylyi revealed various unique gene clusters in A. baumannii, many of which are implicated in virulence, including 133-kb island harboring type IV secretion system homologs akin to those in Legionella and Coxiella. Additional virulence-related genes encode cell envelope components, pilus biogenesis machinery, and iron acquisition systems [64].

Focused studies have illuminated critical virulence mechanisms, including siderophore-mediated iron sequestration [65,66], biofilm formation [67], adherence via outer membrane proteins [68] (OMPs), and the immunostimulatory role of lipopolysaccharide [69] (LPS). To circumvent host-imposed iron limitation, A. baumannii secretes structurally diverse low-molecular-weight siderophores [65,66] whose expression exhibits pronounced strain variability and shares homology with siderophores from aquatic pathogens [66] such as Vibrio anguillarum. Its proclivity for biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces-aided by exopolysaccharide synthesis and type I pili encoded by the csu operon homologous to chaperone-usher pilus systems underpins its resilience in nosocomial environments [67]. Adherence to human bronchial epithelial cells and erythrocytes is mediated by pilus-like appendages, with notable clonal variation, including heightened adhesion among European clone II strains [68]. Subsequently, A. baumannii induces apoptosis via Omp38, an OMP targeting mitochondria and triggering both caspase-dependent and independent apoptotic cascades, though partial attenuation in Omp38 mutants suggests auxiliary cytotoxic effectors [70]. Moreover, A. baumannii harbors up to four quorum-sensing systems orchestrating diverse virulence gene expression, underscoring the sophistication of its regulatory networks.

Infection Control Perspective: The Persistence of Acinetobacter Baumannii as a Nosocomial/Hospital Pathogen

A. baumannii’s tenacity as a nosocomial pathogen is underpinned by a triad of critical factors: pervasive multidrug resistance, extraordinary desiccation resilience, and partial tolerance to commonly employed disinfectants [71,72]. Epidemic strains exhibit elevated resistance profiles, particularly against fluoroquinolones and carbapenems, granting them a pronounced selective advantage in antimicrobial-saturated environments such as intensive care units [72]. This selective pressure fosters the persistence and clonal expansion of multidrug-resistant lineages over prolonged periods [72]. Furthermore, A. baumannii demonstrates an exceptional capacity to survive desiccation, with average survival times on dry surfaces approaching a month, markedly surpassing that of many other gram-negative bacteria. This prolonged viability on fomites and inanimate surfaces significantly contributes to its environmental persistence and facilitates indirect transmission within healthcare settings.

Although comprehensive resistance to disinfectants has not been conclusively established as a primary driver of outbreaks, suboptimal disinfection practices such as insufficient contact times or diluted biocide concentrations, may enable survival of viable bacteria, thus promoting nosocomial dissemination [71,72]. Current evidence suggests that minor procedural lapses rather than intrinsic biocide resistance are responsible for persistence post-cleaning. These intertwined factors multidrug resistance, desiccation endurance, and adaptive tolerance to disinfection synergistically fortify A. baumannii’s ability to persist and propagate in clinical environments, posing significant challenges to infection control and outbreak mitigation [19,71,72]. Despite the growing threat posed by multidrug-resistant A. baumannii, routine diagnostic methods in clinical microbiology laboratories often lag behind technological advances. Traditional culture-based identification, although reliable, is time-consuming and lacks resolution in differentiating between closely related Acinetobacter species, which can lead to diagnostic ambiguity and delayed treatment decisions.

In recent years, several modern tools have enhanced diagnostic precision and turnaround time. Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization–Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) has become a cornerstone in clinical microbiology for rapid species-level identification of A. baumannii. This technology offers high-throughput, accurate, and cost-effective identification within minutes, significantly reducing diagnostic delays. However, its ability to distinguish A. baumannii from other members of the A. calcoaceticus- A. baumannii complex remains limited without additional confirmatory testing. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has also emerged as a powerful tool, particularly for outbreak investigations, antimicrobial resistance gene profiling, and high-resolution strain typing. Whole genome sequencing enables precise phylogenetic analysis, identification of resistance determinants, and epidemiological tracking of MDR clones in healthcare settings. Although NGS is not yet routine in most diagnostic laboratories due to cost, infrastructure, and turnaround time, its clinical utility is increasingly recognized. In contrast, metagenomic sequencing approaches have the potential to identify pathogens and resistance mechanisms directly from clinical specimens, bypassing culture altogether. Integrating these advanced diagnostics into routine clinical practice would not only enhance pathogen detection and resistance profiling but also inform more targeted therapeutic interventions and infection control strategies which could be the key elements in managing MDR A. baumannii infections effectively.

Conclusions

In light of the escalating threat posed by MDR Acinetobacter baumannii, the development of novel therapeutic strategies has become an urgent priority in clinical microbiology and pharmaceutical research. This review highlights the structural versatility and pharmacodynamic adaptability of pyrazole derivatives as promising antimicrobial candidates, capable of circumventing conventional resistance mechanisms. Pyrazoles exhibit notable structural versatility, which facilitates targeted modifications to enhance bioactivity, selectivity, and pharmacological profiles. Integrating structure–activity relationship (SAR) insights with microbiological data enables rational design of potent analogs with improved efficacy against resistant strains. Moreover, understanding microbiological perspective and molecular interactions at the pathogen interface particularly with regard to membrane permeability, efflux evasion, and target engagement offers critical advantages in guiding compound optimization. While initial in vitro and preliminary in silico studies underscore the efficacy of various pyrazole derivatives, translation into clinical utility demands further in vivo validation and comprehensive toxicological assessments. Thus, the adaptability of pyrazole derivatives positions them as strategic candidates for hybrid drug design and combinatorial regimens aimed at overcoming complex resistance mechanisms. The rigorous in vivo validation establishes their clinical relevance, while solubility optimization overcomes the limitations associated poor aqueous solubility that often hinder oral absorption and systemic availability. Likewise, nanoparticle-based formulations can protect the drug from premature degradation, enhance controlled release, and improve tissue targeting, thereby maximizing bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy. Further, by integrating SAR-driven therapeutic discovery with modern diagnostic capabilities offers a promising path forward in combating A. baumannii. As rapid diagnostic platforms-such as MALDI-TOF MS, PCR panels, and next-generation sequencing-enable timely species identification and resistance profiling, they can be leveraged to guide the clinical deployment of rationally designed pyrazole derivatives. SAR data not only inform lead optimization but also allow for targeted therapeutic design against resistance mechanisms identified through molecular diagnostics. Embedding SAR-guided molecules within diagnostic-informed treatment algorithms could facilitate precision therapy, reduce empirical antibiotic use, and improve patient outcomes. The synergistic integration of medicinal chemistry, advanced microbiological diagnostics, and computational biology is crucial for advancing pyrazole-based therapeutics as potent and reliable agents in the emerging post-antimicrobial era.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges Kyoto University and Indian Institute of Technology Jammu for literature access. The author is also thankful to the reviewers for their suggestions at the revision stage of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

The literature search was conducted using PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus. Data sharing is not applicable to this study, as no new data were generated or analyzed.

References

2. Verma SK, Rangappa S, Verma R, Xue F, Verma S, Sharath Kumar KS, et a. Sulfur (SⅥ)-containing heterocyclic hybrids as antibacterial agents against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and its SAR. Bioorg Chem. 2024 Apr;145:107241.

3. Ahmed SK, Hussein S, Qurbani K, Ibrahim RH, Fareeq A, Mahmood KA, et al. Antimicrobial resistance: Impacts, challenges, and future prospects. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health. 2024 Apr 1;2:100081.

4. Zhao X, Verma R, Sridhara MB, Sharath Kumar KS. Fluorinated azoles as effective weapons in fight against methicillin-resistance staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and its SAR studies. Bioorg Chem. 2024 Feb;143:106975.

5. Mulani MS, Kamble EE, Kumkar SN, Tawre MS, Pardesi KR. Emerging Strategies to Combat ESKAPE Pathogens in the Era of Antimicrobial Resistance: A Review. Front Microbiol. 2019 Apr 1;10:539.

6. Silhavy TJ, Kahne D, Walker S. The bacterial cell envelope. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010 May;2(5):a000414.

7. Tavares TD, Antunes JC, Padrão J, Ribeiro AI, Zille A, Amorim MTP, et al. Activity of Specialized Biomolecules against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020 Jun 9;9(6):314.

8. Wang J, Long S, Liu Z, Rakesh KP, Verma R, Verma SK, et al. Structure-activity relationship studies of thiazole agents with potential anti methicillin-resistance Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) activity. Process Biochemistry. 2023 Sep 1;132:13–29.

9. Rhomberg PR, Jones RN. Summary Trends for the Meropenem Yearly Susceptibility Test Information Collection Program: A 10-Year Experience in the United States (2015–2024). Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2025;93:114–21.

10. Verma R, Verma SK, Verma S, Vaishnav Y, Banjare L, Yadav R, et al. Azole and chlorine: An effective combination in battle against methicillin-resistance staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and its SAR studies. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2024 Mar 15;1300:137283.

11. Abraham EP, Chain E. An enzyme from bacteria able to destroy penicillin. 1940. Rev Infect Dis. 1988 Jul-Aug;10(4):677–8.

12. Kumar KS, Ananda H, Rangappa S, Raghavan SC, Rangappa KS. Regioselective competitive synthesis of 3, 5-bis (het) aryl pyrrole-2-carboxylates/carbonitriles vs. β-enaminones from β-thioxoketones. Tetrahedron Letters. 2021 Oct 12;82:153373.

13. Falagas ME, Kasiakou SK. Colistin: the revival of polymyxins for the management of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 May 1;40(9):1333–41.

14. Cai Y, Chai D, Wang R, Liang B, Bai N. Colistin resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii: clinical reports, mechanisms and antimicrobial strategies. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012 Jul;67(7):1607–15.

15. Ananda H, Sharath Kumar KS, Sudhanva MS, Rangappa S, Rangappa KS. A trisubstituted pyrazole derivative reduces DMBA-induced mammary tumor growth in rats by inhibiting estrogen receptor-α expression. Mol Cell Biochem. 2018 Dec;449(1-2):137–144.

16. Kapri A, Gupta N, Nain S. Therapeutic potential of pyrazole containing compounds: an updated review. Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal. 2024 May;58(2):252–67.

17. Mortada S, Karrouchi K, Hamza EH, Oulmidi A, Bhat MA, Mamad H, et al. Synthesis, structural characterizations, in vitro biological evaluation and computational investigations of pyrazole derivatives as potential antidiabetic and antioxidant agents. Scientific Reports. 2024 Jan 15;14(1):1312.

18. Rehman MU, He F, Shu X, Guo J, Liu Z, Cao S, et al. Antibacterial and antifungal pyrazoles based on different construction strategies. Eur J Med Chem. 2025 Jan 15;282:117081.

19. Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008 Jul;21(3):538–82.

20. Eldaly SM, Metwally NH. Green synthesis of some new azolopyrimidines as antibacterial agents based on thiophene-chalcone. Synthetic Communications. 2024 Mar 3;54(5):348–70.

21. Amin NH, El-Saadi MT, Ibrahim AA, Abdel-Rahman HM. Design, synthesis and mechanistic study of new 1,2,4-triazole derivatives as antimicrobial agents. Bioorg Chem. 2021 Jun;111:104841.

22. Pokhodylo N, Manko N, Finiuk N, Klyuchivska O, Matiychuk V, Obushak M, et al. Primary discovery of 1-aryl-5-substituted-1H-1, 2, 3-triazole-4-carboxamides as promising antimicrobial agents. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2021 Dec 15;1246:131146.

23. Sannio F, Brizzi A, Del Prete R, Avigliano M, Simone T, Pagli C, et al. Optimization of Pyrazole Compounds as Antibiotic Adjuvants Active against Colistin- and Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022 Dec 16;11(12):1832.

24. Mugnaini C, Sannio F, Brizzi A, Del Prete R, Simone T, Ferraro T, et al. Screen of Unfocused Libraries Identified Compounds with Direct or Synergistic Antibacterial Activity. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2020 Mar 6;11(5):899–905.

25. Alkhaibari I, Kc HR, Angappulige DH, Gilmore D, Alam MA. Novel pyrazoles as potent growth inhibitors of staphylococci, enterococci and Acinetobacter baumannii bacteria. Future Med Chem. 2022 Feb;14(4):233–44.

26. Delancey E, Allison D, Kc HR, Gilmore DF, Fite T, Basnakian AG, et al. Synthesis of 4,4'-(4-Formyl-1H-pyrazole-1,3-diyl)dibenzoic Acid Derivatives as Narrow Spectrum Antibiotics for the Potential Treatment of Acinetobacter Baumannii Infections. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020 Sep 28;9(10):650.

27. Allison D, Delancey E, Ramey H, Williams C, Alsharif ZA, Al-Khattabi H, et al. Synthesis and antimicrobial studies of novel derivatives of 4-(4-formyl-3-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)benzoic acid as potent anti-Acinetobacter baumannii agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2017 Feb 1;27(3):387–92.

28. Alnufaie R, Raj Kc H, Alsup N, Whitt J, Andrew Chambers S, Gilmore D, et al. Synthesis and Antimicrobial Studies of Coumarin-Substituted Pyrazole Derivatives as Potent Anti-Staphylococcus aureus Agents. Molecules. 2020 Jun 15;25(12):2758.

29. Jagadish S, Hemshekhar M, NaveenKumar SK, Sharath Kumar KS, Sundaram MS, Basappa, et al. Novel oxolane derivative DMTD mitigates high glucose-induced erythrocyte apoptosis by regulating oxidative stress. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2017 Nov 1;334:167–79.

30. Gebremariam T, Zhang L, Alkhazraji S, Gu Y, Youssef EG, Tong Z, et al. Preserving Vascular Integrity Protects Mice against Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacterial Infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020 Jul 22;64(8):e00303–20.

31. Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards JE, Gilbert D, Rice LB, et al. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Jan 1;48(1):1-12.

32. Whitt, J., C. Duke, M. A. Ali, et al. 2019. “Synthesis and Antimicrobial Studies of 4-[3-(3-Fluorophenyl)-4-Formyl-1H-Pyrazol-1-Yl]Benzoic Acid and 4-[3-(4-Fluorophenyl)-4-Formyl-1H-Pyrazol-1-Yl]Benzoic Acid as Potent Growth Inhibitors of Drug- Resistant Bacteria.” ACS Omega 4: 14284–93.

33. Whitt J, Duke C, Sumlin A, Chambers SA, Alnufaie R, Gilmore D, et al. Synthesis of Hydrazone Derivatives of 4-[4-Formyl-3-(2-oxochromen-3-yl) pyrazol-1-yl] benzoic acid as Potent Growth Inhibitors of Antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Acinetobacter baumannii. Molecules. 2019 May 29;24(11):2051.

34. Shah P, Westwell AD. The role of fluorine in medicinal chemistry. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2007 Oct;22(5):527–40.

35. Ali Mohamed H, Ammar YA, A M Elhagali G, A Eyada H, S Aboul-Magd D, Ragab A. In Vitro Antimicrobial Evaluation, Single-Point Resistance Study, and Radiosterilization of Novel Pyrazole Incorporating Thiazol-4-one/Thiophene Derivatives as Dual DNA Gyrase and DHFR Inhibitors against MDR Pathogens. ACS Omega. 2022 Feb 3;7(6):4970–90.

36. Ahmad G, Rasool N, Qamar MU, Alam MM, Kosar N, Mahmood T, et al. Facile synthesis of 4-aryl-N-(5-methyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl) benzamides via Suzuki Miyaura reaction: antibacterial activity against clinically isolated NDM-1-positive bacteria and their Docking Studies. Arabian Journal of Chemistry. 2021 Aug 1;14(8):103270.

37. Alfei S, Caviglia D, Zorzoli A, Marimpietri D, Spallarossa A, Lusardi M, et al. Potent and Broad-Spectrum Bactericidal Activity of a Nanotechnologically Manipulated Novel Pyrazole. Biomedicines. 2022 Apr 15;10(4):907.

38. Schito AM, Caviglia D, Brullo C, Zorzoli A, Marimpietri D, Alfei S. Enhanced Antibacterial Activity of a Cationic Macromolecule by Its Complexation with a Weakly Active Pyrazole Derivative. Biomedicines. 2022 Jul 6;10(7):1607.

39. Lusardi M, Rotolo C, Ponassi M, Iervasi E, Rosano C, Spallarossa A. One-Pot Synthesis and Antiproliferative Activity of Highly Functionalized Pyrazole Derivatives. ChemMedChem. 2022 Mar 4;17(5):e202100670.

40. Hassan AS, Moustafa GO, Askar AA, Naglah AM, Al-Omar MA. Synthesis and antibacterial evaluation of fused pyrazoles and Schiff bases. Synthetic Communications. 2018 Nov 2;48(21):2761–72.

41. Braun-Cornejo M, Platteschorre M, de Vries V, Bravo P, Sonawane V, Hamed MM, et al. Positive Charge in an Antimalarial Compound Unlocks Broad-Spectrum Antibacterial Activity. JACS Au. 2025 Feb 21;5(3):1146–56.

42. Abu-Zaied MA, Elgemeie GH, Mohamed-Ezzat RA. Novel Acrylamide-Pyrazole Conjugates: Design, Synthesis and Antimicrobial Evaluation. Egyptian Journal of Chemistry. 2024 Dec 1;67(13):529–36.

43. Falagas ME, Bliziotis IA, Siempos II. Attributable mortality of Acinetobacter baumannii infections in critically ill patients: a systematic review of matched cohort and case-control studies. Crit Care. 2006;10(2):R48.

44. Falagas ME, Kopterides P, Siempos II. Attributable mortality of Acinetobacter baumannii infection among critically ill patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2006 Aug 1;43(3):389; author reply 389–90.

45. Sunenshine RH, Wright MO, Maragakis LL, Harris AD, Song X, Hebden J, et al. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter infection mortality rate and length of hospitalization. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007 Jan;13(1):97–103.

46. Jinadatha C, Smith J, Patel R. Whole-genome sequencing of Acinetobacter baumannii isolates: Insights into hospital transmission and resistance mechanisms. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2025;63:e01234.

47. Dung TTN, Phat VV, Vinh C, Lan NPH, Phuong NLN, Ngan LTQ, et al. Development and validation of multiplex real-time PCR for simultaneous detection of six bacterial pathogens causing lower respiratory tract infections and antimicrobial resistance genes. BMC Infect Dis. 2024 Feb 7;24(1):164.

48. Garnacho J, Sole-Violan J, Sa-Borges M, Diaz E, Rello J. Clinical impact of pneumonia caused by Acinetobacter baumannii in intubated patients: a matched cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2003 Oct;31(10):2478–82.

49. Loh LC, Yii CT, Lai KK, Seevaunnamtum SP, Pushparasah G, Tong JM. Acinetobacter baumannii respiratory isolates in ventilated patients are associated with prolonged hospital stay. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006 Jun;12(6):597–8.

50. García-Garmendia JL, Ortiz-Leyba C, Garnacho-Montero J, Jiménez-Jiménez FJ, Monterrubio-Villar J, Gili-Miner M. Mortality and the increase in length of stay attributable to the acquisition of Acinetobacter in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 1999 Sep;27(9):1794–9

51. Kwon KT, Oh WS, Song JH, Chang HH, Jung SI, Kim SW, et al. Impact of imipenem resistance on mortality in patients with Acinetobacter bacteraemia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007 Mar;59(3):525–30.

52. Lortholary O, Fagon JY, Hoi AB, Slama MA, Pierre J, Giral P, Rosenzweig R, Gutmann L, Safar M, Acar J. Nosocomial acquisition of multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii: risk factors and prognosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1995 Apr;20(4):790–6.

53. Playford EG, Craig JC, Iredell JR. Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in intensive care unit patients: risk factors for acquisition, infection and their consequences. J Hosp Infect. 2007 Mar;65(3):204–11.

54. Jerassy Z, Yinnon AM, Mazouz-Cohen S, Benenson S, Schlesinger Y, Rudensky B, et al. Prospective hospital-wide studies of 505 patients with nosocomial bacteraemia in 1997 and 2002. J Hosp Infect. 2006 Feb;62(2):230–6.

55. Robenshtok E, Paul M, Leibovici L, Fraser A, Pitlik S, Ostfeld I, et al. The significance of Acinetobacter baumannii bacteraemia compared with Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteraemia: risk factors and outcomes. J Hosp Infect. 2006 Nov;64(3):282–7.

56. Gkrania-Klotsas E, Hershow RC. Colonization or infection with multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii may be an independent risk factor for increased mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2006 Nov 1;43(9):1224–5.

57. Leung WS, Chu CM, Tsang KY, Lo FH, Lo KF, Ho PL. Fulminant community-acquired Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia as a distinct clinical syndrome. Chest. 2006 Jan;129(1):102–9.

58. Lin SY, Wong WW, Fung CP, Liu CE, Liu CY. Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-baumannii complex bacteremia: analysis of 82 cases. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 1998 Jun;31(2):119–24.

59. Rodríguez-Baño J, Pascual A, Gálvez J, Muniain MA, Ríos MJ, Martínez-Martínez L, et al. Bacteriemias por Acinetobacter baumannii: características clínicas y pronósticas [Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia: clinical and prognostic features]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2003 May;21(5):242–7.

60. Grupper M, Sprecher H, Mashiach T, Finkelstein R. Attributable mortality of nosocomial Acinetobacter bacteremia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007 Mar;28(3):293–8.

61. Sunenshine RH, Wright MO, Maragakis LL, Harris AD, Song X, Hebden J, et al. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter infection mortality rate and length of hospitalization. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007 Jan;13(1):97–103.

62. Choi SH, Choo EJ, Kwak YG, Kim MY, Jun JB, Kim MN, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of bacteremia caused by Acinetobacter species other than A. baumannii: comparison with A. baumannii bacteremia. J Infect Chemother. 2006 Dec;12(6):380–6.

63. Fournier PE, Vallenet D, Barbe V, Audic S, Ogata H, Poirel L, et al. Comparative genomics of multidrug resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS Genet. 2006 Jan;2(1):e7.

64. Smith MG, Gianoulis TA, Pukatzki S, Mekalanos JJ, Ornston LN, Gerstein M, et al. New insights into Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenesis revealed by high-density pyrosequencing and transposon mutagenesis. Genes Dev. 2007 Mar 1;21(5):601–14.

65. Dorsey CW, Beglin MS, Actis LA. Detection and analysis of iron uptake components expressed by Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2003 Sep;41(9):4188–93.

66. Dorsey CW, Tomaras AP, Connerly PL, Tolmasky ME, Crosa JH, Actis LA. The siderophore-mediated iron acquisition systems of Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606 and Vibrio anguillarum 775 are structurally and functionally related. Microbiology (Reading). 2004 Nov;150(Pt 11):3657–67.

67. Tomaras AP, Dorsey CW, Edelmann RE, Actis LA. Attachment to and biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces by Acinetobacter baumannii: involvement of a novel chaperone-usher pili assembly system. Microbiology (Reading). 2003 Dec;149(Pt 12):3473–84.

68. Lee JC, Koerten H, van den Broek P, Beekhuizen H, Wolterbeek R, van den Barselaar M, et al. Adherence of Acinetobacter baumannii strains to human bronchial epithelial cells. Res Microbiol. 2006 May;157(4):360–6.

69. Haseley SR, Holst O, Brade H. Structural studies of the O-antigen isolated from the phenol-soluble lipopolysaccharide of Acinetobacter baumannii (DNA group 2) strain 9. Eur J Biochem. 1998 Jan 15;251(1-2):189–94.

70. Choi CH, Lee EY, Lee YC, Park TI, Kim HJ, Hyun SH, et al. Outer membrane protein 38 of Acinetobacter baumannii localizes to the mitochondria and induces apoptosis of epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol. 2005 Aug;7(8):1127–38.

71. Jawad A, Seifert H, Snelling AM, Heritage J, Hawkey PM. Survival of Acinetobacter baumannii on dry surfaces: comparison of outbreak and sporadic isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998 Jul;36(7):1938–41.

72. Koeleman JG, van der Bijl MW, Stoof J, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Savelkoul PH. Antibiotic resistance is a major risk factor for epidemic behavior of Acinetobacter baumannii. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001 May;22(5):284–8.