Abstract

Inflammation is a complex biological process essential for protecting the body from harmful stimuli. However, dysregulated or chronic inflammation can contribute to the pathogenesis of various diseases, including asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, and gout. Pro-inflammatory enzymes, such as arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase (A5-LOX), xanthine oxidase, and hyaluronidase, play key roles in the initiation, progression, and resolution of inflammation. A5-LOX catalyzes the production of leukotrienes, potent mediators of immune cell recruitment and activation, which are implicated in allergic and inflammatory responses. Xanthine oxidase contributes to oxidative stress and inflammation through the generation of reactive oxygen species during purine metabolism, and its inhibition offers therapeutic potential for diseases like gout. Hyaluronidase, by degrading hyaluronic acid, disrupts the extracellular matrix, leading to increased tissue permeability and exacerbating inflammation, as seen in conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis. This review examines the roles of these enzymes in inflammatory diseases and explores their potential as therapeutic targets. Inhibition of A5-LOX, xanthine oxidase and hyaluronidase present promising strategies for managing chronic inflammatory diseases, with ongoing research focused on developing more selective and effective enzyme inhibitors. Understanding the molecular mechanisms behind these enzymes may lead to novel, more precise treatments for inflammatory diseases, improving patient outcomes.

Keywords

Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase, Enzyme inhibitors, Hyaluronidase, Inflammation, Inflammatory mediators, Pro-inflammatory enzymes, Therapeutic targets, Xanthine oxidase

Introduction

Inflammation is a complex biological response of the immune system designed to eliminate harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, allergic or chemical irritants and toxic compounds, as well as to repair tissue damage. It serves as a protective mechanism that involves immune cells, blood vessels and various molecular mediators to neutralize the injurious stimuli and initiate the healing process. Erythema, edema, heat, pain, and altered function are the cardinal signs of inflammation [1-5]. In the absence of inflammation, wounds would fail to heal, infections would persist, and progressive tissue damage would ultimately threaten the survival of the host [2,6]. However, when inflammation becomes uncontrolled, it can lead to excessive tissue damage. If inflammatory proteins continue to accumulate throughout the body, they directly and indirectly cause various diseases. Inflammation is involved in the disease processes of allergies, arteriosclerosis, autoimmune diseases, dementia, eye diseases, and even certain types of cancer [4,5,7].

Pro-inflammatory enzymes play a pivotal role in initiation, progression and resolution of inflammation. These enzymes, including arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase (A5-LOX), xanthine oxidase, and hyaluronidase, are involved in the synthesis of key inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and reactive oxygen species (ROS), which regulate immune responses. Dysregulation or overactivation of these enzymes can lead to chronic inflammation, which is implicated in a wide range of inflammatory diseases [3,4,8,9]. This review explores the roles of A5-LOX, xanthine oxidase, and hyaluronidase in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases. Understanding the multifaceted contributions of these enzymes could provide novel insights into the development of more effective therapeutic strategies for managing inflammatory diseases.

Acute and Chronic Inflammation

Acute inflammation is the immediate biochemical and cellular response of the body to harmful stimuli. At the onset of an infection, burn or other injury, immune cells are activated and inflammatory mediators, which are responsible for the clinical signs of inflammation, are released. Acute inflammation is initiated by resident immune cells already present in the injured tissues and continued with the increased movement of plasma and leukocytes from the blood into the injured tissues. A cascade of biochemical events propagates and matures the inflammatory response, involving the local vascular system, immune system and various cells within the injured tissue [1,2,6]. During acute inflammatory responses, cellular and molecular events and interactions efficiently minimize the impending injury or infection. This mitigation process contributes to restoration of tissue homeostasis and resolution of acute inflammation. However, if uncontrolled, acute inflammation may become chronic, contributing to a variety of chronic inflammatory diseases [3].

Inflammation becomes chronic due to the persistence of the initiating factors and to a failure of mechanisms required for resolving the inflammatory response. Thus, chronic inflammation promotes whether directly or indirectly an increase in cell proliferation, an enhancement of inflammatory cell recruitment and excessive production of ROS, reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and active proteolytic enzymes [10]. Chronic inflammation leads to a progressive shift in the type of cells which are present at the site of inflammation and is characterized by simultaneous destruction and healing of the tissue from the inflammatory process [2,5]. It can lead to a multitude of diseases, including hay fever, periodontitis, atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, gout, Alzheimer’s disease and obesity, and can even cause cancers such as gallbladder carcinoma [11].

As a result of the local immune, vascular, and inflammatory cell responses to the infection or injury, clinical signs of inflammation including redness, increasing temperature, swelling, pain, and loss of function are emerged. However, not all five signs occur in every inflammation as some inflammations do not cause any symptoms. These clinical signs reflect the increased blood flow and capillary permeability, release of inflammatory mediators and leukocyte migration to the site of inflammation. Many different immune cells can take part in inflammation and they release different inflammatory mediators causing the narrow blood vessels in the tissue to expand and increase the blood flow to the inflamed area. Consequently, the inflamed area turns red and becomes hot. The inflammatory mediators increase the permeability of the narrow vessels, allowing more defense cells to enter the site of inflammation. The defense cells also carry more fluid into the inflamed tissue and swelling occurs due to the accumulation of fluid. Inflammatory mediators stimulate nerve endings and increase the sensitivity to pain. When an inflamed limb can no longer be moved properly or when the sense of smell is worse during a cold or when it is more difficult to breathe while having bronchitis, it is known as loss of function and it occurs due to a combination of factors [1,3,12,13].

Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase Enzyme

Lipoxygenases are a family of non-heme, non-sulphur, iron cofactor containing dioxygenases (oxidoreductase enzymes) that are widely distributed in animals and plants. In human tissues, lipoxygenases are expressed in platelets, eosinophils, synovial fluids, neutrophils, colonic tissues, lung tissues, monocytes, and bone marrow cells [14]. Lipoxygenases catalyze the addition of molecular oxygen to polyunsaturated fatty acids, containing a cis, cis-1,4-pentadiene, such as linoleic, linolenic and arachidonic acid to yield unsaturated fatty acid hydroperoxides which can act as cell signaling agents [14-16]. In mammalian cells, lipoxygenases are the key enzymes which are involved in the biosynthesis of a variety of bioregulatory compounds such as hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids, leukotrienes, lipoxins, and hepoxylines [15,17]. Lipoxygenases are capable of generating lipid mediators such as leukotrines and prostaglandins, which are capable of inducing inflammation and allergic symptoms. Lipoxygenase products play a key role in a variety of diseases such as bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular diseases, tumor angiogenesis, and certain types of cancer [5,14,15,17,18]. Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase (EC 1.13.11.34) is a member of the lipoxygenase family of enzymes. It involves in the biosynthesis of potent mediators of inflammatory disorders and allergic reactions. It is the key enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of leukotrienes and catalyzes the initial steps in the conversion of arachidonic acid to biologically active leukotrienes by introducing an oxygen molecule at the fifth carbon of the arachidonic acid chain [4,18,19].

Leukotrienes

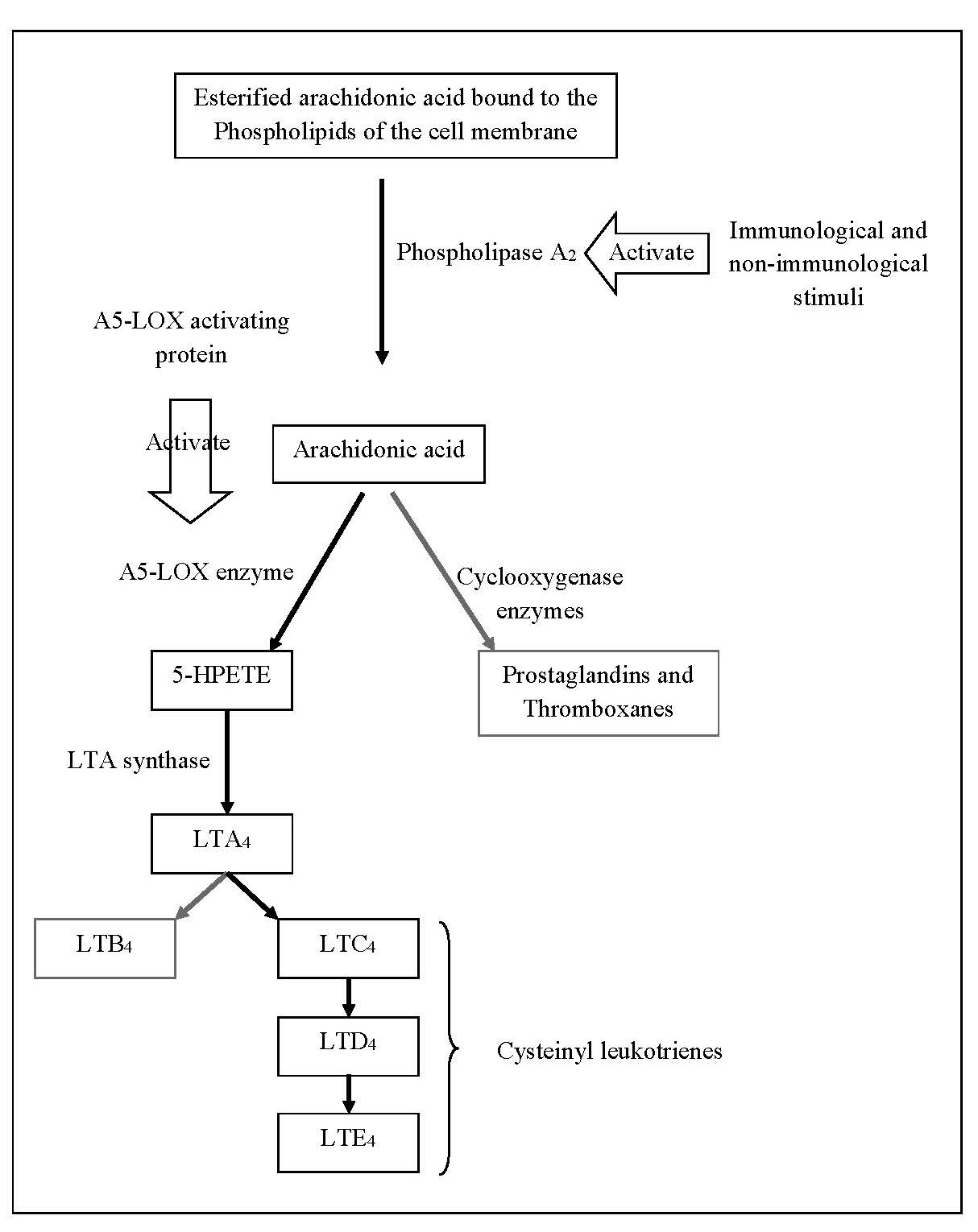

Leukotrienes are lipid mediators that play a central role in the recruitment and activation of immune cells such as neutrophils, eosinophils and macrophages, at the sites of inflammation. They are a group of signaling molecules produced in white blood cells (leukocytes) by the oxidation of arachidonic acid which is a polyunsaturated, 20-carbon fatty acid [19,20]. However, the over activity of A5-LOX or excessive production of leukotrienes is linked to the pathogenesis of a number of inflammatory diseases including asthma, allergic rhinitis, chronic bronchitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease as well as allergic reactions. Leukotrienes contribute to vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and the promotion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. They contribute to the signs and symptoms seen in inflammatory responses [14,19,20]. The esterified form of arachidonic acid is bound to the phospholipids of the cell membranes. Both immunological and non-immunological stimuli can activate the enzyme phospholipase A2 and release arachidonic acid from the membrane phospholipids. The released arachidonic acid is oxidized by several distinct enzyme pathways including the cyclooxygenase pathway, which produces prostaglandins and thromboxanes, and the lipoxygenase pathway, which produces leukotrienes and other intermediate compounds. In the lipoxygenase pathway, a nuclear membrane protein, A5-LOX activating protein, activates A5-LOX enzyme to oxidize arachidonic acid to 5 hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid (5-HPETE) which is the precursor of the leukotrienes.. Then 5-HPETE is converted into a series of leukotrienes and the nature of the final product varies according to the tissue. The enzyme LTA synthase catalyze the conversion of 5-HPETE to unstable leukotriene A4 (LTA4) which is then converted to either leukotriene B4 (LTB4) or leukotriene C4 (LTC4). LTC4 is actively transported out of cells and metabolized rapidly to leukotriene D4 (LTD4) and then to leukotriene E4 (LTE4). LTC4, LTD4 and LTE4 are referred to as the cysteinyl (Cys) leukotrienes because of their chemical structure. LTE4 is either excreted in the urine or metabolized to a variety of biologically less active or inactive metabolites, including leukotriene F4 (LTF4) [14,20]. The main pathways of formation of leukotrienes are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Main pathways involved in the formation of leukotrienes.

Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase Inhibitors

Since leukotrienes are considered as potent mediators of inflammatory and allergic reactions, inhibition of the lipoxygenase pathway is important in the prevention and treatment of a variety of inflammatory diseases. Therefore, A5-LOX is a potential target for the rational drug design to discover mechanism-based inhibitors for the treatment of inflammatory diseases [4,17,20]. Using A5-LOX inhibitors such as Zileuton and Montelukast in the treatment of asthma and allergies confirms the therapeutic significance of blocking the biosynthesis of the leukotrienes by the inhibition of A5-LOX, in the treatment of inflammatory diseases [20,21].

Xanthine Oxidase Enzyme

Xanthine oxidase (EC 1.17.3.2) is a member of the oxidoreductases class of enzymes. It is a molybdoflavin enzyme responsible for catalyzing the terminal two reactions in purine degradation in primates; oxidation of hypoxanthine to xanthine and subsequently oxidation of xanthine to uric acid [5,22,23]. Uric acid undergoes no further metabolism in humans due to the absence of urate oxidase and is excreted by the kidneys and gastrointestinal tract [24,25]. Excessive production and/or inadequate excretion of uric acid results in hyperuricemia leading to the deposition of monosodium urate crystals in joints or kidneys causing gouty arthritis or uric acid nephrolithiasis [26,27]. Therefore, urate-lowering treatments either increasing the excretion of uric acid or reducing the uric acid production are required for the prevention and treatment of conditions associated with hyperuricemia. Urate-lowering agents include xanthine oxidase inhibitors, uricosuric agents and uricase agents [24,25].

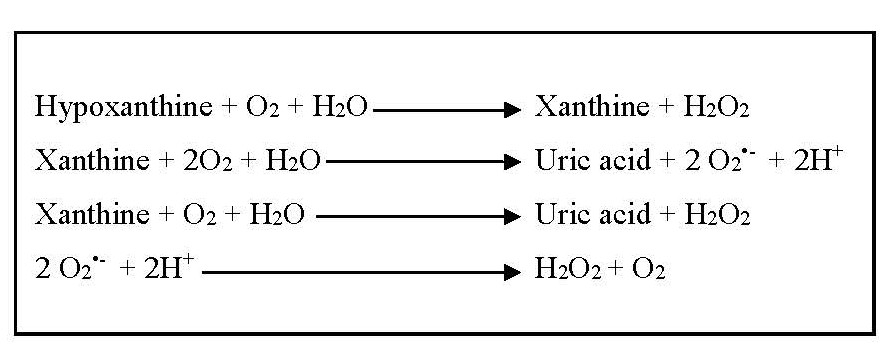

During the oxidation of hypoxanthine and xanthine, and then xanthine to uric acid, superoxide anions and hydrogen peroxide, which are considered as ROS, are formed. Spontaneously or under the influence of superoxide dismutase enzyme, superoxide anions are converted into hydrogen peroxide and oxygen [24]. Due to the formation of ROS during the catalytic action (Figure 2), xanthine oxidase contributes to oxidative stress and plays a pathogenetic role in various forms of inflammatory diseases other than gout, several types of tissue and vascular injuries, and chronic heart failure [4,21,22].

Figure 2. Formation of reactive oxygen species due to the catalytic actions of xanthine oxidase.

Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors

Since xanthine oxidase plays an important role in the pathogenesis of inflammation via different pathways, inhibiting xanthine oxidase is considered as a target for the management of diseases associated with oxidative stress and inflammation [18]. Xanthine oxidase inhibitors are recognized as appropriate candidates for various therapeutic indications accompanied by the function of xanthine oxidase [5,21]. Inhibition of xanthine oxidase blocks the biosynthesis of uric acid and consequently reduces circulating levels of uric acid and reduces vascular oxidative stress. Xanthine oxidase inhibitors have been used as treatments for gout and uricemia. Inhibiting xanthine oxidase also has therapeutic potential for other inflammatory diseases where oxidative stress is a contributing factor. Allopurinol, oxypurinol, febuxostat, and probenecid are among the many known xanthine oxidase inhibitors [5,25]. However, they have side effects such as induction of drug resistance, inhibition of anticancer drug metabolism, and aplastic anemia [5]. Although allopurinol is the most commonly prescribed synthetic xanthine oxidase inhibitor widely used in the management of conditions associated with hyperuricemia and related inflammatory diseases, it is associated with several side effects including allergies, gastrointestinal distress, liver function abnormalities, and a fatal complication known as “allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome” [22]. Therefore, there is an increasing demand for alternative xanthine oxidase inhibitors.

Hyaluronic acid

Hyaluronic acid is a mucopolysaccharide composed of D-glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine linked via the hexosaminidic bonds in β (1→4) linkages. It usually consists of 2,000 to 2,500 disaccharides to give a molecular mass between 106 and 107 Da and extended lengths of 2 to 25 µm. It is generally found in the extracellular matrix, especially in soft connective tissues, skin, cartilage and in the capsule of some bacteria [5,28]. Hyaluronic acid plays an important role in several biological processes such as cellular adhesion, water balance and osmotic pressure regulation, mobility differentiation processes, where it acts as a lubricant and a shock absorber, and maintenance of tissue architecture [28,29]. It can regulate inflammatory responses by inhibiting the phagocytosis of macrophages [5].

Hyaluronidase Enzyme

Hyaluronidase (EC 3.2.1.35) is one of the lysosomal enzymes which hydrolyzes mucopolysaccharides including hyaluronic acid [5,30]. Hyaluronidase cleaves the β-1,4-glycosidic bonds in hyaluronic acid, breaking it down into smaller oligosaccharides. This alters the structure and function of the extracellular matrix. Hyaluronidase involves in a number of physiological regulatory processes and pathological conditions including increased vascular permeability, destruction of extracellular matrix, embryogenesis, angiogenesis, inflammation, disease progression, wound healing, bacterial pathogenesis, diffusion of systemic venoms, and invasion of tumors. Hyaluronidase usually exists in an inactive form and is activated by antigens, compound 48/80 and certain metal ions including calcium ions [31]. The in vivo activation of hyaluronidase by metal ions leads to degranulation of mast cells, causing the release of inflammatory mediators. In inflammatory conditions, excessive hyaluronidase activity can promote tissue breakdown, increase vascular permeability, and facilitate the migration of inflammatory cells into tissues. Hyaluronidase also enhances the spread of infection by breaking down tissue barriers and facilitating the movement of pathogens. Hyaluronic acid is present in synovial fluid in joints as a viscous lubricating agent and hyaluronidase degrades it by lowering its viscosity and increasing the permeability. The degradation of hyaluronic acid by hyaluronidase results in changes to tissue hydration, viscoelasticity, and cell signaling. Hyaluronidase is involved in conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, where its activity contributes to the breakdown of cartilage and the spread of inflammation. In rheumatoid arthritis, excessive degradation of hyaluronic acid by hyaluronidase causes depletion of its amount and molecular weight consequently producing arthritic symptoms [18,21,30].

Hyaluronidase Inhibitors

Inhibition of hyaluronic acid degradation is critical and imperative in controlling hyaluronidase mediated pathological conditions. Hyaluronidase inhibitors serve as anti-inflammatory agents as well as anti-aging, antimicrobial, anticancer, antivenom/toxin, and contraceptive agents. Hyaluronidase inhibitors have therapeutic potential in limiting tissue destruction and inflammatory responses. The search for hyaluronidase inhibitors is important to identify new potent antiallergic and anti-inflammatory compounds which can serve as effective therapeutic agents [4,5,21,32].

Conclusion

A5-LOX, xanthine oxidase and hyaluronidase are critical enzymes in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases, playing essential roles in the initiation, progression, and resolution of inflammation. These enzymes mediate inflammatory responses through the production of inflammatory mediators, such as leukotrienes and reactive oxygen species, and the degradation of extracellular matrix components. Dysregulation of these enzymes leads to the persistence and escalation of chronic inflammation, contributing to diseases such as asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, and gout. The therapeutic potential of targeting A5-LOX, xanthine oxidase, and hyaluronidase has already been demonstrated with inhibitors like zileuton, allopurinol, and various hyaluronidase inhibitors. These therapies have shown efficacy in reducing inflammatory symptoms and improving patient outcomes in certain conditions. However, there remains a void to be filled with more selective inhibitors which minimize side effects and enhance therapeutic benefits. Future research is crucial for further elucidating the complex mechanisms underlying these enzymes' roles in inflammation and for discovering novel compounds that can better control their activity. By advancing our understanding of these enzymes, we may be able to provide more effective, targeted treatments that not only manage inflammation but also offer long-term solutions for patients suffering from chronic inflammatory diseases.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

2. Gajendra NJ, Madhavi E, Konda VG, Venkata RY, Rajeshwaramma G. Comparative study of anti-inflammatory activity of newer macrolides with etoricoxib. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences. 2014 Mar 10;3(10):2413-20.

3. Chen L, Deng H, Cui H, Fang J, Zuo Z, Deng J, et al. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget. 2017 Dec 14;9(6):7204-18.

4. Jayawardana SAS, Samarasekera JKRR, Hettiarachchi GHCM, Gooneratne J, Choudhary MI, Jabeen A. Anti-inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of Finger Millet (Eleusine coracana (L.) Gaertn.) Varieties Cultivated in Sri Lanka. Biomed Res Int. 2021 Oct 1;2021:7744961.

5. Moon SH, Lim Y, Huh MK. Lipoxygenases, Hyaluronidase, and Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitory Effects Extracted from Five Hydrocotyle Species. Biomedical Science Letters. 2021 Dec 31;27(4):277-82.

6. Neeraja K, Nimmagada R, Remella SKDS, Manasa RV. Comparision of anti-inflammatory effect of newer macrolides with etoricoxib in 0.1ml of 1% carrageenan induced rat hind paw oedema by digital plethysmograph. IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences. 2016;15(12):25-8.

7. Sagnia B, Fedeli D, Casetti R, Montesano C, Falcioni G, Colizzi V. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of extracts from Cassia alata, Eleusine indica, Eremomastax speciosa, Carica papaya and Polyscias fulva medicinal plants collected in Cameroon. PLoS One. 2014 Aug 4;9(8):e103999.

8. Mbhele N, Ncube B, Ndhlala AR, Moteetee A. Pro-inflammatory enzyme inhibition and antioxidant activity of six scientifically unexplored indigenous plants traditionally used in South Africa to treat wounds. South African Journal of Botany. 2022 Jul 1;147:119-29.

9. Lim JR, Chua LS, Mustaffa AA. Pro-inflammatory enzyme inhibition of lipoxygenases by flavonoid rich extract from Artemisia vulgaris. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2024 Apr 15;1237:124072.

10. Elkahwaji JE. The role of inflammatory mediators in the development of prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Res Rep Urol. 2012 Dec 31;5:1-10.

11. AlAjmi MF, Hussain A, Alsalme A, Khan RA. In Vivo assessment of newly synthesized achiral copper (ii) and zinc (ii) complexes of a benzimidazole derived scaffold as a potential analgesic, antipyretic and anti-inflammatory. RSC Advances. 2016;6(23):19475-81.

12. Chandrasoma P, Taylor CR. Concise Pathology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1998.

13. Bennett JM, Reeves G, Billman GE, Sturmberg JP. Inflammation-Nature's Way to Efficiently Respond to All Types of Challenges: Implications for Understanding and Managing "the Epidemic" of Chronic Diseases. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018 Nov 27;5:316.

14. Shah SA, Ashraf M, Ahmad I, Arshad S, Yar M, Latif A. Anti-lipoxygenase activity of some indigenous medicinal plants. J. Med. Plants Res. 2013 Feb 10;7(6):219-22.

15. Kucukboyaci N, Orhan I, Sener B, Nawaz SA, Choudhary MI. Assessment of enzyme inhibitory and antioxidant activities of lignans from Taxus baccata L. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2010 Mar-Apr;65(3-4):187-94.

16. Chedea VS, Vicaş SI, Socaciu C, Nagaya T, Ogola HJ, Yokota K, et al. Lipoxygenase-quercetin interaction: A kinetic study through biochemical and spectroscopy approaches. In: Jimenez-Lopez JC, editor. Biochemical Testing. Rijeka: IntechOpen; 2012 Mar 7; p. 151-78.

17. Ahmad I, Chen S, Peng Y, Chen S, Xu L. Lipoxygenase inhibiting and antioxidant iridoids from Buddleja crispa. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2008 Feb;23(1):140-3.

18. Perera HDSM, Samarasekera JKRR, Handunnetti SM, Weerasena OVDSJ, Weeratunga HD, Jabeen A, et al. In vitro pro-inflammatory enzyme inhibition and anti-oxidant potential of selected Sri Lankan medicinal plants. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018 Oct 3;18(1):271.

19. Schneider I, Bucar F. Lipoxygenase inhibitors from natural plant sources. Part 1: Medicinal plants with inhibitory activity on arachidonate 5‐lipoxygenase and 5‐lipoxygenase [sol] cyclooxygenase. Phytotherapy research: An International Journal Devoted to Pharmacological and Toxicological Evaluation of Natural Product Derivatives. 2005 Feb;19(2):81-102.

20. O'Donnell SR. Leukotrienes-biosynthesis and mechanisms of action. Australian Prescriber. 1999 Jun 1;22(3):55.

21. Perera HD, Samarasekera JK, Handunnetti SM, Weerasena OV. In vitro anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant activities of Sri Lankan medicinal plants. Industrial Crops and Products. 2016 Dec 30;94:610-20.

22. Azmi SM, Jamal P, Amid A. Xanthine oxidase inhibitory activity from potential Malaysian medicinal plant as remedies for gout. International Food Research Journal. 2012 Feb 1;19(1):159-65.

23. Cantu-Medellin N, Kelley EE. Xanthine oxidoreductase-catalyzed reduction of nitrite to nitric oxide: insights regarding where, when and how. Nitric Oxide. 2013 Nov 1;34:19-26.

24. Argulla LE, Chichioco-Hernandez CL. Xanthine oxidase inhibitory activity of some Leguminosae plants. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease. 2014 Dec 1;4(6):438-41.

25. Kostić DA, Dimitrijević DS, Stojanović GS, Palić IR, Đorđević AS, Ickovski JD. Xanthine oxidase: isolation, assays of activity, and inhibition. Journal of Chemistry. 2015;2015(1):294858.

26. Sowndhararajan K, Joseph JM, Rajendrakumaran D. In vitro xanthine oxidase inhibitory activity of methanol extracts of Erythrina indica Lam. leaves and stem bark. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 2012 Jan 1;2(3):S1415-7.

27. Wong YP, Ng RC, Chuah SP, Koh RY, Ling AP. Antioxidant and xanthine oxidase inhibitory activities of Swietenia macrophylla and Punica granatum. InInternational Conference on Biological, Environment and Food Engineering (BEFE-2014), August 2014 Aug 4 (pp. 4-5).

28. Abdullah NH, Thomas NF, Sivasothy Y, Lee VS, Liew SY, Noorbatcha IA, et al. Hyaluronidase Inhibitory Activity of Pentacylic Triterpenoids from Prismatomeris tetrandra (Roxb.) K. Schum: Isolation, Synthesis and QSAR Study. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 Feb 14;17(2):143.

29. Suzuki A, Toyoda H, Toida T, Imanari T. Preparation and inhibitory activity on hyaluronidase of fully O-sulfated hyaluro-oligosaccharides. Glycobiology. 2001 Jan;11(1):57-64.

30. Choudhary MI, Thomsen WJ. Bioassay techniques for drug development. Singapore: Harwood Academic Publishers; 2001.

31. Abhijit Sahasrabudhe AS, Manjushree Deodhar MD. Anti-hyaluronidase, anti-elastase activity of Garcinia indica. International Journal of Botany. 2010;6:299-303.

32. Girish KS, Kemparaju K, Nagaraju S, Vishwanath BS. Hyaluronidase inhibitors: a biological and therapeutic perspective. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16(18):2261-88.