Commentary

The number of individuals with all-stage chronic kidney disease (CKD) reached almost 700 million in 2017, which is more people than those with diabetes, osteoarthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, or depressive disorders [1]. A multitude of studies have been published in the field of CKD based on patho-physiological considerations, screening, etiological factors, clinical observations, targeted therapeutic interventions, but very little is known about the fate of a patient, who has CKD and who is followed for years by his treating physician and the reference nephrologist.

In the Emilia-Romagna Region of Italy, the public health service has long been focused on the issue of CKD . Big efforts have been made towards identifying the best solutions to address the needs to promote prevention and appropriate care of CKD patients and to research modalities in patient care and outcomes in real-world nephrology practices.

In particular, the regional project Prevention of Progression of Renal Disease (PIRP) was established in 2004, with the early recognition of the disease in people with known risk factors and the implementation of primary prevention strategies and monitoring of patients being treated as main purposes. More in detail, the project aims were: i) the reduction of CKD progression towards ESRD; ii) the prevention of the onset of cardiovascular complications and the reduction of their burden; iii) an appropriate, effective and efficient continuity of care of CKD patients based on outpatient care; iiii) the integrated management of CKD patients between general practitioners and nephrologists in order to reduce disease progression, complications and hospitalizations.

As a secondary aim of the PIRP project, we sought to establish a representative real-world cohort of nephrology-referred CKD patients, stratified by center size and geographic location by including consecutive consenting patients into a project registry. This procedure resulted in a fairly representative selection of CKD patients with kidney disease. The cohort of CKD patients included in the PIRP registry has been described in an article that summarizes their characteristics and outcomes [2]. The recruited cohort comprised mostly elderly patients with predominantly hypertensive/vascular and diabetic kidney disease. As expected, primary kidney disease diagnoses differed considerably among age groups, and patients carried a high burden of co-morbidities, especially diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. With the cooperation of GPs, in its 16 years of activity, the project identified and followed up on more than 31,000 CKD patients, who attended the Nephrology units with more than 133,000 visits as of August 2020. The effects of a closer and joint monitoring of CKD patients by GPs and nephrologists can be represented by the reduction of the mean annual GFR decline (average annual CKD-EPI change: -0.34 ml/min), and by the decrease in the overall number of patients who annually started dialysis in the Emilia-Romagna Region. This number dropped from 780 in 2006 to 676 in 2015.

Furthermore, having a population of patients with CKD followed over the years allows a series of longitudinal investigations that are not possible in cross-sectional studies or in follow-up studies carried over a short time period.

Specifically, in 2013 we developed a classification tree model (hereafter named CT-PIRP) to stratify patients according to their annual estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decline [3]. This model identified seven subgroups (nodes) characterized by specific combinations of six variables (gender, age, proteinuria, baseline eGFR, phosphate levels, diabetes) which were associated with different levels of eGFR decline. Recently, we proposed a temporal validation of the CT-PIRP prognostic model for mortality and renal replacement therapy initiation [4]. In this study, we found that the overall mean annual eGFR decline was -1.33 ± 5.16 ml/min (Table 1). It was faster in node 1 (proteinuria and GFR >33.65 ml/min), node 5 (diabetic patients with no proteinuria and age <67 years) and node 3 which included patients with proteinuria, GFR <33.65 ml/min and phosphate more than 4.3 mg/dl, with a rate of annual eGFR decline of -3.66; -2.97; -2.83 mL/min respectively. Nodes at the low rate of progression were node 6 (female without proteinuria and age >67.7 years) and node 7 (males without proteinuria and age >67.7 years). In these last nodes the change in GFR was +0.06 ml/min in node 6 and -0.84 mL/min in node 7. In summary, it is still confirmed that factors of kidney damage progression and reduction of GFR are proteinuria, diabetes, high levels of phosphorus, and young age. While the absence of proteinuria and an age greater than 67 years is associated to a slight annual loss of GFR or, in women, to stable values on the average, even in the presence of a reduced GFR. Both of these characteristics, i.e. no proteinuria and age over 67 years, have a low risk of kidney death and need for dialysis therapies after 6 years of follow-up in the project (around 19%). On the contrary, node 3 patients (with proteinuria, phosphate >4.3 mg/dl and GFR <33.6 ml/min) have the highest risk of renal replacement therapy at 6 years (71.9%).

|

Node |

Variables |

Mean eGFR annual reduction |

|

1 |

Proteinuria, GFR > 33.65 ml/min |

-3.66 ml/min |

|

2 |

Proteinuria, GFR < 33.65 ml/min, PO4 <4,3 mg/dl |

-1.36 ml/min |

|

3 |

Proteinuria, GFR < 33.65, PO4 > 4.3 mg/dl |

-2.83 ml/min |

|

4 |

No diabetes, age< 67.7 years, no proteinuria |

-1.34 ml/min |

|

5 |

Diabetes, age< 67.7 years, no proteinuria |

-2.97 ml/min |

|

6 |

Females, age >67.7 years, no proteinuria |

+0.06 ml/min |

|

7 |

Males, age >67.7 years, no proteinuria |

-0.84 ml/min |

Mortality risk ranged between 41.1% and 49.1% for nodes 3, 6 and 7, 35.7% for node 2, 30.0% for node 5, while it was lower for nodes 4 and 1 (9.1% and 18.0% respectively). The latter four nodes showed a significantly lower mortality risk than node 7 (non-proteinuria, older, male patients).

Two of the six variables included in the model, eGFR and the presence of proteinuria, are widely recognized as key risk modifiers of adverse renal outcomes [5-8]. The use of eGFR change as a much better predictor of adverse renal outcomes than the absolute GFR value has been advocated by several authors [2,9-11] based on the assumption that it incorporates the effect of pharmaceutical-dietary treatment [11,12] and of physiological factors such as the reduced muscle mass associated with chronic illness [5,6].

In CT-PIRP, mean eGFR change is not explicitly specified as a model parameter; however, it should be seen as embedded into the definition of subgroups. The high mortality in PIRP, over 40%, confirms once again that, in CKD patients, the risk of dying is much greater than the risk going on dialysis. On the other hand, in the world deaths due to CKD and cardiovascular disease deaths attributable to impaired kidney function, represented 4·6% (95% UI 4·3 to 5·0) of total mortality. Ranked as the 17th leading cause of death in 1990, CKD has increased in importance, ranking as the 12th leading cause of death in 2017 [13].

As reported by a recent Lancet article [1], CKD due to diabetes accounted for 30.7% (95% UI 27.8 to 34.0) of CKD DALYs (disability-adjusted life year), the largest contribution in terms of absolute number of DALYs of any cause in 2017, with CKD due to type 1 and type 2 diabetes resulting in 2.9 million (2.4 to 3.5) DALYs and 8.1 million (7.1 to 9.2) DALYs. In CKD patients followed in the PIRP project, the prevalence of diabetes is about 35%. We recently analyzed the behavior of the diabetic population within PIRP CKD patients in terms of disease progression, time of arrival to dialysis and risk of death. We only considered patients who had at least three medical visits in their follow-up. Thus we considered 15957 patients, 35% females and 65% males. The non-diabetic patients were 10,359, while 5,498 patients with diabetes. The diabetic had a greater eGFR decrease (Figure 1) in comparison with patients without diabetes (-1.55 vs. -0.82 ml/min/1.73 m2).

Figure 1: Average annual reduction in eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) in CKD patients with diabetes and without diabetes. Patients with at least 3 visits (n=15,857).

For years it was thought that the diabetic patient with the worst prognosis was the diabetic with proteinuria and at times with a real nephrotic syndrome [14]. Over the past few years many studies have demonstrated that non-albuminuric renal impairment is the predominant clinical phenotype in patients, particularly women, with reduced eGFR [15]. Findings from recent clinical trials suggest that hyperfiltration driven by the sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 and the renin–angiotensin system is a common upstream mechanism that drives kidney disease in both DKD and NDKD in the context of diabetes mellitus [16,17]. We evaluated in our PIRP patients for which at least three visits were recorded how the presence of diabetes affected outcomes. For this, we used propensity score matching (PSM) and calculated ATET [Average treatment effect on treated] of diabetes for dialysis and mortality, considering gender, age, baseline GFR, nephrology unit and year of enrollment in PIRP as matching factors. We obtained two matched populations composed of 5498 diabetics and 5498 non-diabetics. The ATET of diabetes for dialysis was 0.0136, indicating a 1.4% higher risk of initiating dialysis compared to non-diabetics (p=0.027) and 0.1040 for mortality, indicating a 10.4% higher risk of mortality (p<0.001).

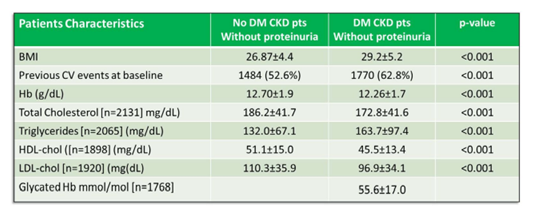

We then wanted to assess whether CKD diabetic patients without proteinuria had the same outcome as CKD non-diabetic patients without proteinuria. In practice, how diabetes regardless of proteinuria, influences outcome in kidney insufficiency. To this aim, two matched cohorts of CKD patients were obtained from the PIRP database. In the period 2005-2017, 2820 subjects with DM in CKD-EPI stages 3a to 5 and without evidence of proteinuria were matched with as many non-DM patients without proteinuria by gender, age class, CKD stage. To assess the presence of a differential mortality risk in diabetic patients, a multiple Cox regression model was fit, adjusted for several potential clinical confounders, using multiple imputation to estimate missing data and correcting the standard error estimates by patients’ clusterization into nephrology units. We found in diabetics a higher percentage of overweight or obese patients than in non-diabetics (38.9% vs 19.6%, p<0.001), lower levels of haemoglobin (12.3 g/dl vs 12.7 g/dl, p<0.001) and higher values of triglycerides (164 mg/dl vs 132 mg/dl, p<0.001) (Table II). Diabetics had higher BMI, a greater number of CV events at baseline. Lower levels of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol were found among diabetic patients presumably caused by the more frequent use of statins.

Table 2: Comparison of physical, clinical, biochemical characteristics between CKD patients without proteinuria and with or without diabetes.

Figure 2: Cardiovascular Events (CV) at baseline, during the follow-up, dialysis inception and death in CKD patients with diabetes and without diabetes. Patients with at least 3 visits (n=15,857).

Ten-year survival was significantly lower in diabetics (31.2% vs 42.5%, log-rank test: p <0.001, Figure 3). Multivariable Cox regression identified a higher mortality risk for diabetics (HR = 1.249, p<0.001) after adjusting for sex, age, baseline eGFR, hemoglobin levels, BMI, smoking status, presence of tumors or cardio-vascular comorbidities.

Figure 3: Kaplan-Meier survival curves for mortality in CKD patients with diabetes and without diabetes. Patients with at least 3 visits (n=15,857).

These data show that in patients with CKD, concurrent diabetes was associated to a higher frequency of CV events and represented an independent risk factor for overall mortality. Thus, in diabetic patients, even in absence of proteinuria , we have to strengthen therapeutic strategies to control the so-called CV intermediate risk factors (tobacco use, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, hypertension, hypercoagulable states, obesity, etc.).

In conclusion, routine care of nephrology-referred patients in Emilia Romagna and followed in PIRP project comprises mostly elderly patients and patients with hypertensive/diabetic kidney disease. The identification of local risk factors for CKD progression (proteinuria, diabetes, high phosphate levels, young age, etc.) may help to optimize the nephrological resources by implementing closer follow-up in patients having a higher risk. CKD progression varied largely within the patient population. While a large proportion of elderly patients displayed low CKD progression rates, others, such as diabetics with or even without albuminuria/proteinuria, have a faster progression towards the end-stages, a higher CV incidence rate and a higher risk of death.

However, for both diabetics and non-diabetics patients, being followed up in a project in which nephrologists and GPs cooperate in the surveillance and management of the patient’s pathway of their kidney disease can lead to a reduction in the rate of progression, to a lower risks of CV and death, and to a substantial reduction in the number of patients reaching the dialysis stage.

References

2. Santoro A, Gibertoni D, Rucci P, Mancini E, Bonucchi D, Buscaroli A, et al. The PIRP project (Prevenzione Insufficienza Renale Progressiva): how to integrate hospital and community maintenance treatment for chronic kidney disease. Journal of Nephrology. 2019 Jun 1;32(3):417-27.

3. Rucci P, Mandreoli M, Gibertoni D, Zuccalà A, Fantini MP, Lenzi J, et al. A clinical stratification tool for chronic kidney disease progression rate based on classification tree analysis. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2014 Mar 1;29(3):603-10.

4. Gibertoni D, Rucci P, Mandreoli M, Corradini M, Martelli D, Russo G, et al. Temporal validation of the CT-PIRP prognostic model for mortality and renal replacement therapy initiation in chronic kidney disease patients. BMC nephrology. 2019 Dec 1;20(1):177.

5. Matsushita K, Selvin E, Bash LD, Franceschini N, Astor BC, Coresh J. Change in estimated GFR associates with coronary heart disease and mortality. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2009 Dec 1;20(12):2617-24.

6. Turin TC, Coresh J, Tonelli M, Stevens PE, De Jong PE, Farmer CK, et al. One-year change in kidney function is associated with an increased mortality risk. American Journal of Nephrology. 2012;36(1):41-9.

7. Shlipak MG, Katz R, Kestenbaum B, Siscovick D, Fried L, Newman A, et al. Rapid decline of kidney function increases cardiovascular risk in the elderly. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2009 Dec 1;20(12):2625-30.

8. Perkins RM, Bucaloiu ID, Kirchner HL, Ashouian N, Hartle JE, Yahya T. GFR decline and mortality risk among patients with chronic kidney disease. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2011 Aug 1;6(8):1879-86.

9. Tangri N, Inker LA, Hiebert B, Wong J, Naimark D, Kent D, et al. A dynamic predictive model for progression of CKD. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2017 Apr 1;69(4):514-20.

10. Schroeder EB, Yang X, Thorp ML, Arnold BM, Tabano DC, Petrik AF, et al. Predicting 5-year risk of RRT in stage 3 or 4 CKD: development and external validation. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2017 Jan 6;12(1):87-94.

11. Ragot S, Saulnier PJ, Velho G, Gand E, de Hauteclocque A, Slaoui Y, et al. Dynamic changes in renal function are associated with major cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016 Jul 1;39(7):1259-66.

12. Bayliss EA, Bhardwaja B, Ross C, Beck A, Lanese DM. Multidisciplinary team care may slow the rate of decline in renal function. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2011 Apr 1;6(4):704-10.

13. James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet. 2018 Nov 10;392(10159):1789-858.

14. Pugliese G, Penno G, Natali A, Barutta F, Di Paolo S, Reboldi G, et al. Diabetic kidney disease: New clinical and therapeutic issues. Joint position statement of the Italian Diabetes Society and the Italian Society of Nephrology on “The natural history of diabetic kidney disease and treatment of hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes and impaired renal function”. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2019 Nov 1;29(11):1127-50.

15. Penno G, Solini A, Orsi E, Bonora E, Fondelli C, Trevisan R, et al. Non-albuminuric renal impairment is a strong predictor of mortality in individuals with type 2 diabetes: the Renal Insufficiency And Cardiovascular Events (RIACE) Italian multicentre study. Diabetologia. 2018 Nov 1;61(11):2277-89.

16. Cherney DZ, Perkins BA, Soleymanlou N, Maione M, Lai V, Lee A, et al. Renal hemodynamic effect of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2014 Feb 4;129(5):587-97.

17. Piperidou A, Loutradis C, Sarafidis P. SGLT-2 inhibitors and nephroprotection: current evidence and future perspectives. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2020 Aug 10:1-4.