Abstract

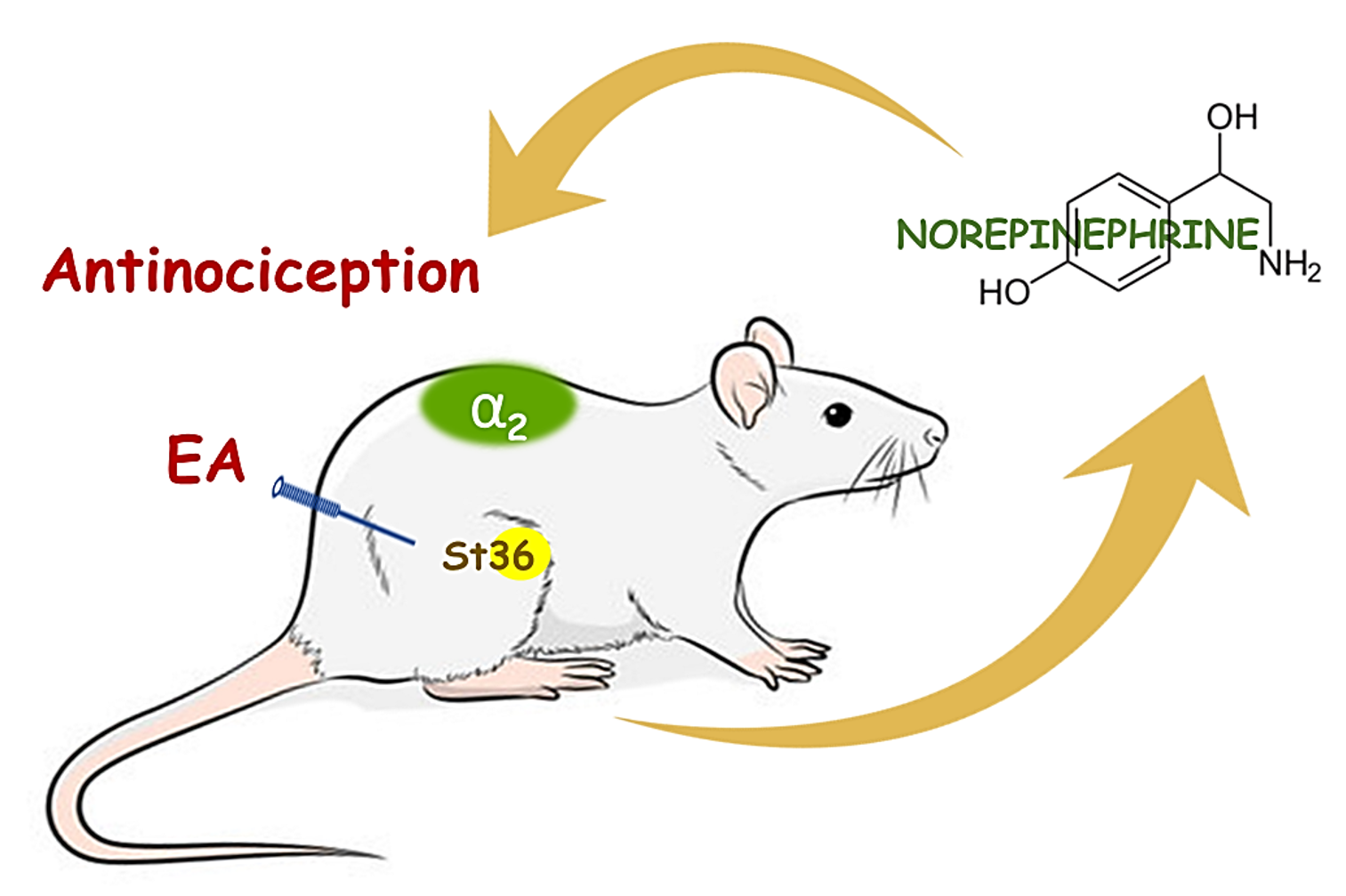

Orofacial pain represents a significant portion of the complaints from patients seeking treatment at pain management centers worldwide. Although the treatment for orofacial pain is primarily pharmacological, there has been an increase in reports showing significant clinical results from non-pharmacological therapies, including electroacupuncture (EA). Recently, EA has been recognized as an effective and affordable non-pharmacological strategy with minimal side effects. However, the mechanisms underlying its pain-relieving (antinociceptive) effects remain poorly understood. The present study aimed to evaluate the roles of α2 adrenoreceptors and GABA in the antinociception induced by electroacupuncture. Male Wistar rats underwent EA stimulation at the acupoint St36 for 20 minutes at a frequency of 100 Hz and an intensity of 0.5 mA. To assess the thermal nociceptive response, a stimulus was applied to the vibrissae (whiskers) of the rats, and the time taken for facial withdrawal was measured before the EA stimulation and at 15-minute intervals afterward until the effects diminished. EA at acupoint St36 for 20 minutes effectively reversed thermal nociception, with this effect lasting for 150 minutes. The antinociceptive effects of EA were blocked by the pre-injection of yohimbine, an antagonist of α2 adrenoreceptors, at doses of 2 and 4 mg/kg. However, it was primarily observed at the onset, indicating that α2 adrenoreceptors play a role in the initial antinociceptive effect of EA. To investigate the involvement of GABA in this effect, intraperitoneal injections of a GABAB antagonist (sacoflen) and a GABA reuptake inhibitor (guvacine) were administered 10 minutes before EA. Neither of these drugs affected the antinociceptive effect produced by EA. Thus, this study suggests that GABA does not participate in the antinociception induced by electroacupuncture.

Keywords

Antinociception, Electroacupuncture, ST36 point, α2 adrenergic receptors, GABA

Introduction

Orofacial pain accounts for a significant proportion of the complaints from patients seeking treatment in pain centers worldwide. A study involving 45,711 individuals in the United States found that approximately 22% reported experiencing orofacial pain [1]. This type of pain typically manifests in the muscles of mastication, the preauricular area, and/or the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). It is transmitted to the central nervous system through the trigeminal nerve, the fifth cranial nerve, which processes sensory input from both the temporomandibular region and other facial structures [2].

There are several treatment strategies for orofacial pain, which primarily include pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches. Among these, electroacupuncture (EA) has gained prominence in recent years due to its cost-effectiveness and minimal side effects compared to traditional pharmacological treatments. Hansen and Hansen conducted one of the earliest clinical studies investigating acupuncture for orofacial pain control in humans in 1983 [3]. In this study, the researchers examined the effects of simultaneous stimulation at acupuncture points VB14, Taiyang, TA5, E2, E3, E6, E7, IG4, and E44 in a group of 20 patients suffering from chronic facial pain for over one year. The study included a comparison to sham acupuncture, which involved needling and electrostimulation at non-specific points. The authors concluded that acupuncture resulted in greater facial pain relief than the placebo treatment [3].

The clinical research team demonstrated the effectiveness of orofacial acupuncture treatment daily, indicating this therapy's reliability [4]. In the same way, another group demonstrated the orofacial analgesic efficacy of acupuncture compared with the sham group using a double-blind evaluation [5]. These results were corroborated by a study using image evaluations produced by functional magnetic resonance imaging. It was demonstrated that electroacupuncture (EA) at the IG4 point in volunteers activated brain areas related to the facial musculature in addition to promoting the deactivation of brain areas related to the pain pathway [6].

The mechanisms underlying electroacupuncture (EA)-induced analgesia remain poorly understood. Recent studies conducted by our group have shown that EA at the ST36 acupuncture point produces significant pain relief in rats exposed to a thermal nociceptive stimulus on the face, specifically in the trigeminal nerve region. Additionally, these studies have identified various endogenous analgesic mediators involved in this effect, including opioids, nitric oxide, and endocannabinoids [7-9]. The effectiveness of acupuncture as an analgesic through noradrenergic modulation remains debatable due to its excitatory nature, whether via α1 receptors or inhibitory via α2 [10]. Even in relation to the inhibitory pathway, in one study, yohimbine, an α2-receptor antagonist, did not block the antinociceptive effect produced by electroacupuncture (EA) at point ST36 in a trigeminal model of nociception induced by pulpal stimulation in rabbits [11]. Conversely, another study found that yohimbine did reverse the antinociceptive effects of EA stimulation at points ID6 and the application of bee venom at point ST36 in models of arthritis pain induced by collagen, as well as pain from ankle sprains in rats [12,13]. Few studies have been conducted on the effects of acupuncture on the inhibitory GABAergic system. One study demonstrated that in an allodynia model, intrathecal injections of GABAA and GABAB receptor antagonists, specifically gabazine and saclofen, were able to inhibit the anti-allodynia effect of acupuncture at the point ST36. This suggests that acupuncture may activate the release of GABA in the spinal cord [14].

Previous research by our group has demonstrated that electrical acupuncture (EA) at the ST36 point produces orofacial antinociception in rats through the involvement of several endogenous mediators. The present study aims to investigate the role of α2 receptors and GABA in this analgesic effect induced by acupuncture.

Material and Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats (obtained from CEBIO-UFMG) weighing between 180 and 230 grams were utilized for the experiments. Two days before testing, the rats were housed in a controlled environment with a temperature of 23 ± 1°C and a 12-hour light/dark cycle (from 07:00 to 19:00 hours), with food and water available ad libitum. All experiments were conducted during the light phase of the cycle. The Animal Care Committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais approved the experiments, which adhered to the ethical guidelines set forth by the International Association for the Study of Pain in Conscious Animals.

Algesimeter method

To evaluate the thermal nociceptive threshold of the face [7], rats were gently restrained for up to 10 seconds with the right side of their face (specifically the vibrissa region) placed across a NiCr wire coil at room temperature (23 ± 2°C). This region was chosen to stimulate the nociceptive endings of the maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve. The coil temperature was then increased by applying an electric current until a head withdrawal reflex was observed. To help the rats acclimate to the algesimeter test, they were habituated to the apparatus twice, one day before the experiments.

The heat intensity was set to 42.6°C, ensuring that the baseline latencies were between 3 and 4 seconds. A cut-off time of 8 seconds was established to minimize the risk of tissue damage.

Electroacupuncture stimulation

This study was conducted using awake rats. To facilitate this, we employed a plastic cylinder to immobilize the rats while allowing access to their hind limbs for the application of acupuncture needles. This setup was previously described by Medeiros et al. [15,16]. The method was chosen for two reasons: 1) to avoid interference from anesthetic procedures that could influence the results, and 2) to ensure that the procedure closely resembles clinical practice. To minimize stress-induced antinociception, the rats were familiarized with the immobilization apparatus for 30 minutes each day over a two-day period before the experiments.

Stainless steel needles (7 x 0.17 mm) were inserted bilaterally into the hind limbs at a depth of 3 mm in acupoint St36, which is located in the anterior tibial muscle, 10 mm distal to the knee joint. St36 was chosen due to its well-documented analgesic effects in mouse pain models. A sham point was also used because there are relatively few acupoints in this area. This sham point was appropriate as it lies between two meridians—the urinary bladder and the gallbladder—and is distant from the frequently used acupoint GB40.

The needles were connected to an electronic pulse generator (Sikuro DS100, Brazil), which produces a burst of bipolar and asymmetric square waves with a pulse duration of 1.5 to 2 ms. The tested frequency was set at 100 Hz. Stimulation was applied for 20 minutes. The stimulus intensity was set at 0.5 mA, which is recognized as a subthreshold. This intensity was established one point below the level necessary to produce detectable muscle twitches or vocalizations in rats to mimic the intensity used in clinical practice closely.

Drugs

The drug used in this study was yohimbine, an α2 receptor antagonist administered at doses of 1, 2, and 4 mg/kg (TOCRIS-USA). It was dissolved in a 0.9% saline solution. Additionally, saclofen, a competitive antagonist for GABAB receptors, was given at a dose of 20 mg/kg (TOCRIS-USA), and guvacine, an inhibitor of GABA cellular uptake, was administered at doses of 20, 40, and 80 mg/kg (TOCRIS-USA). Both saclofen and guvacine were also dissolved in 0.9% saline. The drugs were injected intraperitoneally at a 1 ml/kg volume 10 minutes before the start of electroacupuncture stimulation.

The groups in the study were organized as follows:

- Dry Needle group (DN): Animals that received needling at the same acupuncture point without any stimulation.

- Electroacupuncture group (EA): Animals that underwent electroacupuncture stimulation for 20 minutes.

- Yoh+EA group: Animals that were pretreated with yohimbine before receiving electroacupuncture.

- Sac+EA group: Animals that were pretreated with a competitive antagonist for the GABAB receptor before undergoing electroacupuncture.

- Guv+EA group: Animals that were pretreated with an inhibitor of GABA cellular uptake before receiving electroacupuncture.

- Control group: Animals that received the same volume of vehicle solution via the same route as the experimental groups.

Experimental protocol

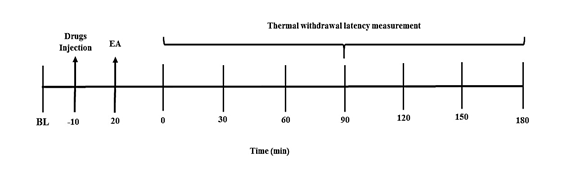

First, we measured the baseline latency (BL) for 20 minutes before electroacupuncture (EA) stimulation. The first nociceptive threshold measurement was taken immediately after the EA stimulation ended, with subsequent measurements taken every 30 minutes.

To examine the roles of norepinephrine and GABA in electroacupuncture-induced antinociception, we measured the BL right before administering the drug or vehicle injections, which occurred 10 minutes before the start of the electroacupuncture stimulation (Figure 1).

Figure 1. (A) Experimental protocol for electroacupuncture stimulation (EA). B) A schematic drawing illustrating the location of the acupoint ST36 (Suzanli) in a rat. BL: baseline latency.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for the evaluated parameters. They were analyzed for statistical significance using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. A minimum significance level of P<0.05 was established. The results are reported as the mean with a 95% two-tailed confidence interval (CI). Statistical analyses and figure preparation were conducted using GraphPad Prism software, Version 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Antinociception induced by EA, at acupoint St36

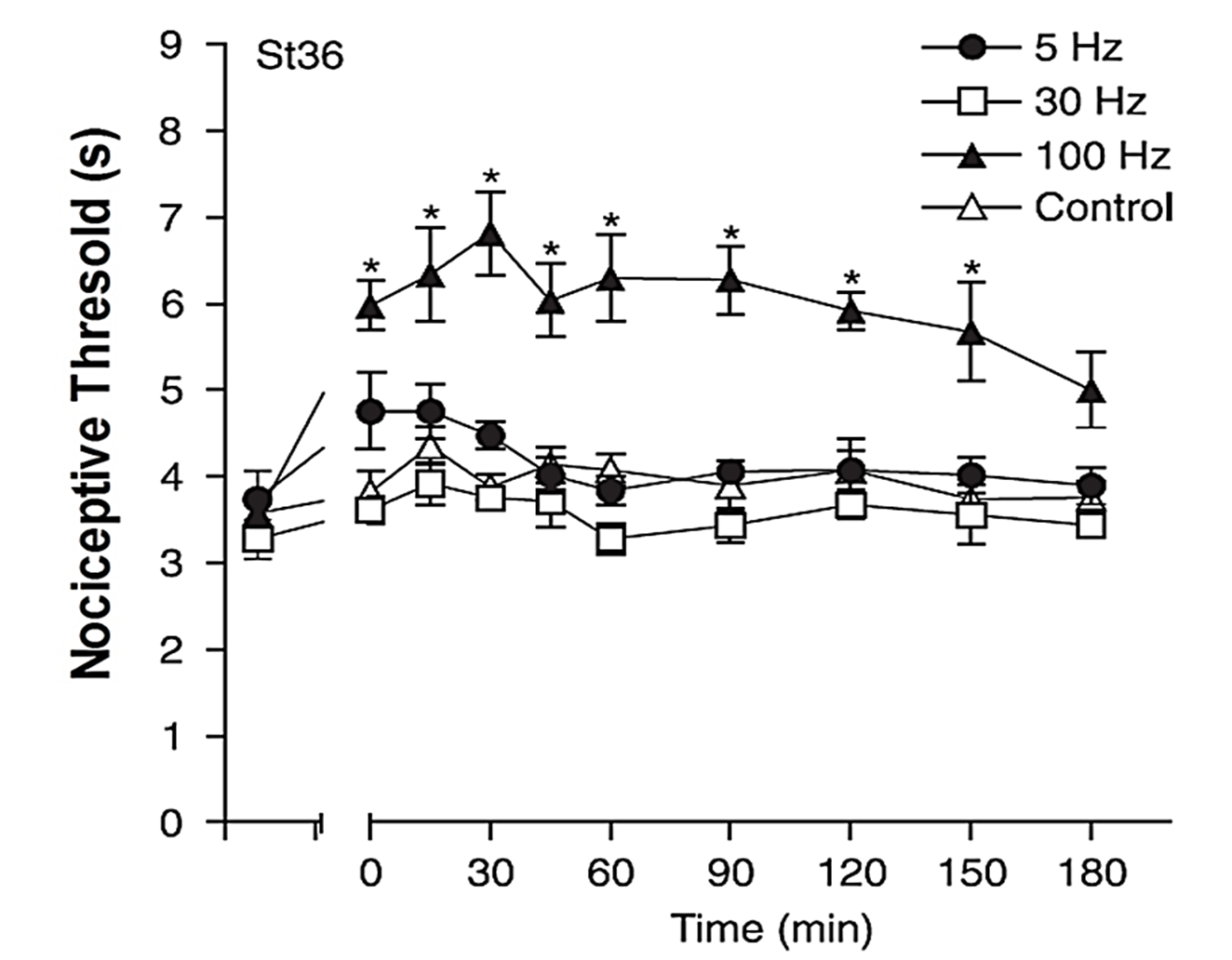

When a frequency of 100 Hz was applied, the stimulation of acupoint St36 significantly increased the nociceptive threshold. This effect began immediately after the electroacupuncture stimulation was terminated, peaked at 30 minutes, and remained statistically significant for 180 minutes. In contrast, the other frequencies tested (5 Hz and 30 Hz) did not produce any antinociceptive effects at any measured time points (Figure 2).

Figure 2:Effect of stimulation frequency on the facial withdrawal threshold assessed after electroacupuncture (EA) stimulation of the acupoint St36. Baseline latency values of 3-4 were recorded from each rat immediately before the onset of EA stimulation, which continued for 20 minutes with adjustments to the stimulation intensity. The control group underwent needle insertion at the same location but did not receive electrical stimulation. Each data point represents the mean threshold ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A statistically significant difference was noted with *P < 0.05 compared to the control group, with N=5 for this study (ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test).

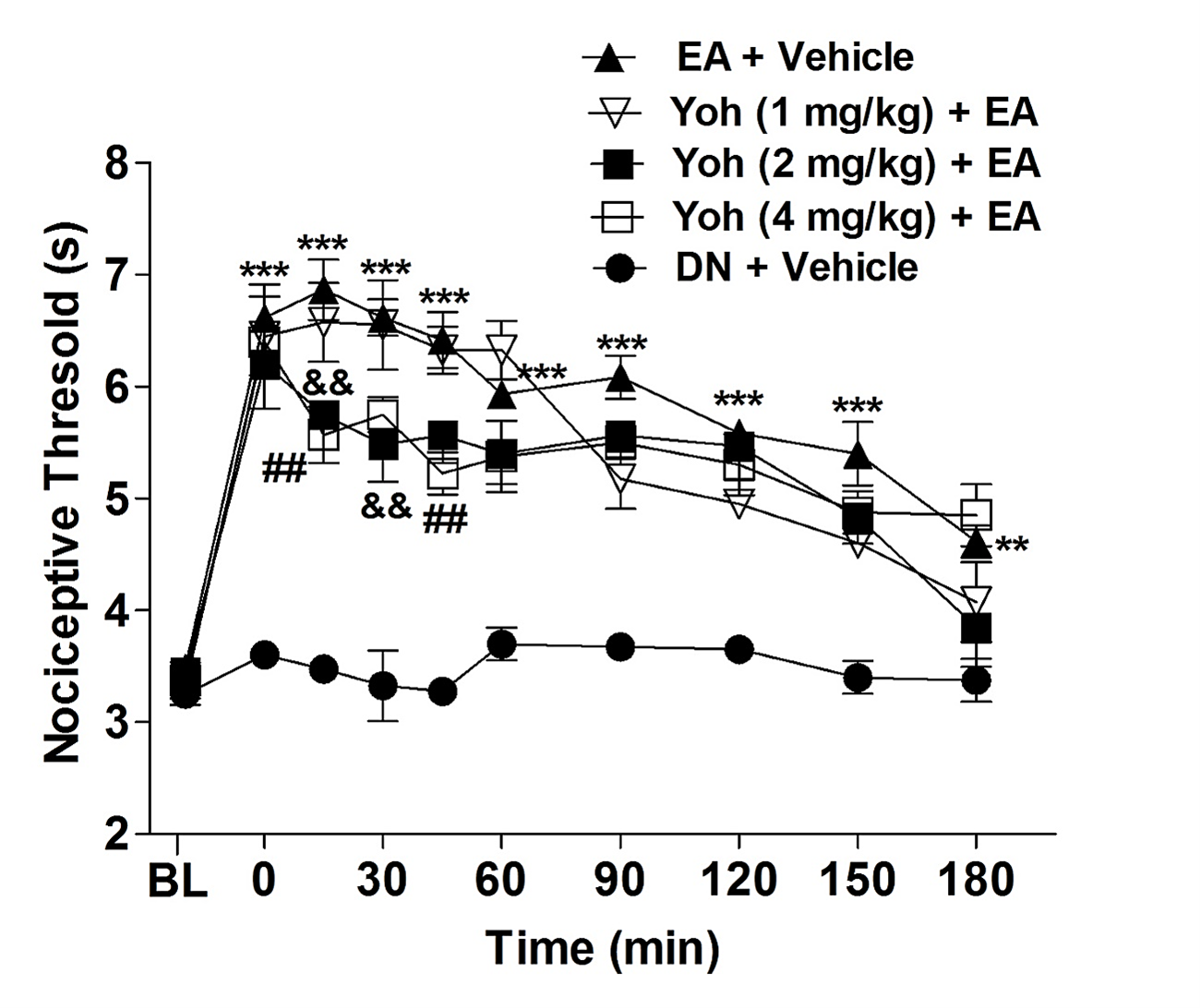

Involvement of α2 adrenergic receptors in the antinociception induced by EA

Subcutaneous administration of yohimbine at doses of 2 mg/kg (measured at 15 and 30 minutes) and 4 mg/kg (measured at 15 and 45 minutes) partially antagonized the antinociception induced by 100 Hz frequency stimulation applied to the acupoint St36. This reduced the latency of the rats to withdraw their faces from a heat source compared to the control group. No significant difference was observed between the 2 mg/kg and 4 mg/kg doses. Additionally, yohimbine at a dose of 1 mg/kg did not antagonize the antinociception induced by stimulation of acupoint St36 (Figure 3). Furthermore, yohimbine administered alone had no effect on the latency to withdraw the face (data not shown).

Figure 3: Effect of yohimbine on antinociception induced by electroacupuncture in orofacial pain. The baseline latency (BL) was measured immediately before the drug injection. Yohimbine (YOH) was administered at doses of 1, 2, and 4 mg/kg via intraplantar injection 10 minutes prior to the onset of electroacupuncture stimulation (EA), which lasted for 20 minutes. The control group received acupuncture at the same point but was injected with a saline solution instead. Each point represents the nociceptive threshold mean ± SEM. ***P<0.001 indicates a significant difference between the animals group that received EA stimulation plus saline injection (EA + Vehicle) and the animals group that received needling without stimulation (Dry Needle = DN) and saline injection (control group, DN + Vehicle); &&P<0.01, indicates a significant difference between the group that received EA stimulation plus saline injection (Sal + EA) and animals that received the yohimbine more EA stimulation (Yoh 2 mg/kg + EA) and ##P<0.01 indicates a significant difference between the group that received EA stimulation plus saline injection (Sal + EA) and animals that received the yohimbine more EA stimulation (Yoh 4 mg/kg + EA), two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test (n=5).

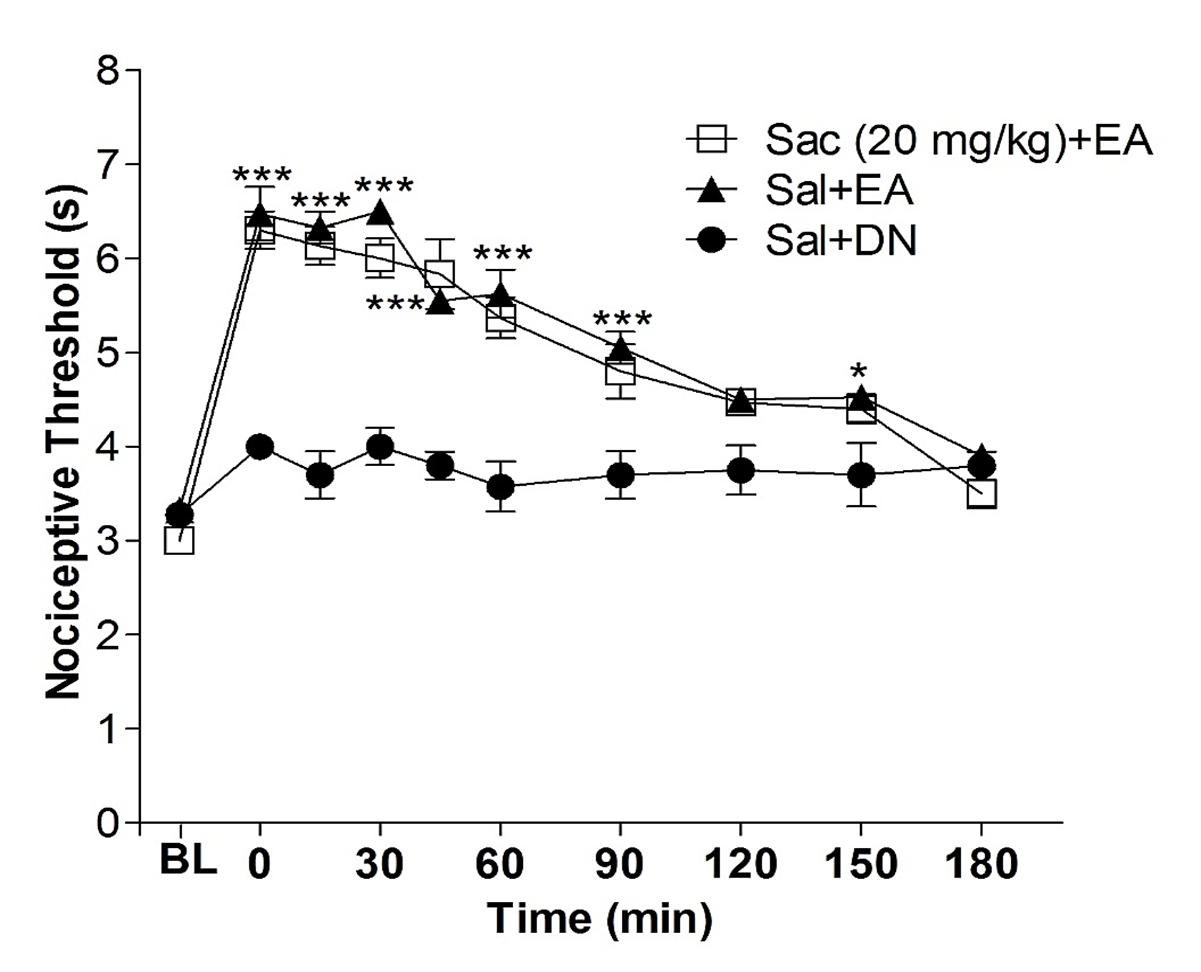

Involvement of GABAB receptors in the antinociception induced by EA

GABA is a crucial inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, particularly in modulating endogenous pain. Therefore, assessing whether this system could be influenced by the acupuncture point E36 was essential. As illustrated in Figure 4, the pre-injection of the GABAB antagonist, saclofen, at a dose that has been considered high (20 mg/kg) in previous experiments did affect the antinociceptive effect produced by electroacupuncture (EA).

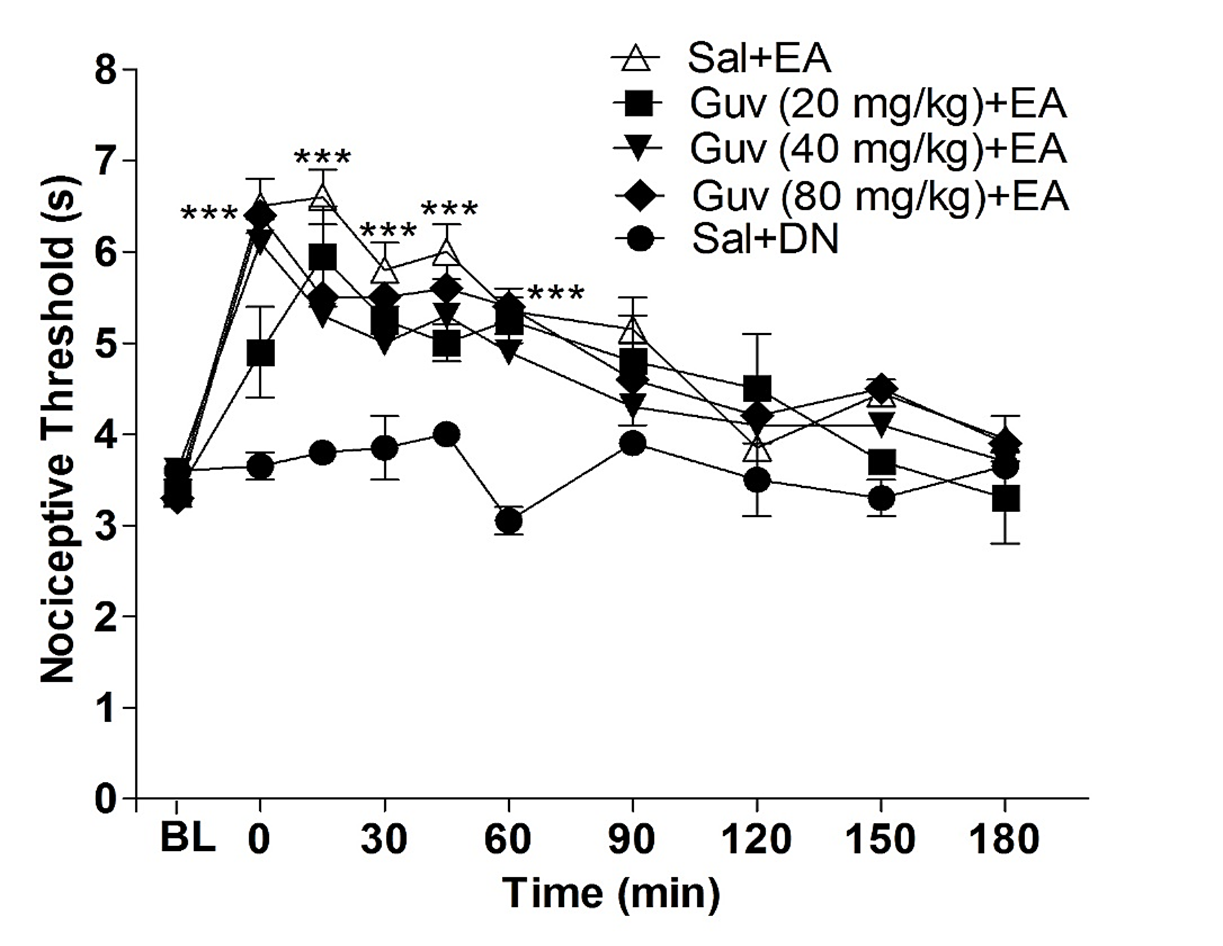

Effect of inhibitor of GABA cellular uptake in the antinociception induced by EA

The use of the GABA reuptake inhibitor guvacine is a valuable tool for studying the role of this neurotransmitter in orofacial antinociception induced by electrical acupuncture (EA) at point E36. Guvacine increases GABA levels in the synaptic cleft, which can enhance and prolong the antinociceptive effects of this neurotransmitter. However, similar to the results shown in Figure 4, administering guvacine at three different doses (20, 40, and 80 mg/kg) before the treatment did not lead to any changes in the EA-induced antinociception (as depicted in Figure 5). The results are also presented in Table 1.

Figure 4. Effect of sacoflen on antinociception induced by electroacupuncture in the orofacial pain. The baseline latency (BL) was obtained immediately before the drug injection. Sacoflen (Sac, 2 mg/kg, i.pl.) was injected 10 min before the onset of the electroacupuncture stimulation (EA), which lasted 20 min. The control group received acupuncture at the same point but with the injection of saline solution. Each point represents the nociceptive threshold mean ± SEM. ***P<0.001 indicates a significant difference between the group that received EA stimulation plus saline injection (Sal + EA) and the group that received needling without stimulation (Dry Needle = DN) and saline injection (control group, Sal + DN), two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test (n=5).

Figure 5. Effect of guvacine on antinociception induced by electroacupuncture in the orofacial pain. The baseline latency (BL) was obtained immediately before the drug injection. Guvacine (Guv, 20, 40, and 80 mg/kg, i.pl.) was injected 10 min before the onset of the electroacupuncture stimulation (EA), which lasted 20 min. The control group received acupuncture at the same point but with the injection of saline solution. Each point represents the nociceptive threshold mean ± SEM. ***P<0.001 indicates a significant difference between the group that received EA stimulation plus saline injection (Sal + EA) and the group that received needling without stimulation (Dry Needle = DN) and saline injection (control group, Sal + DN), two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test (n= 5).

|

GROUPS |

Nociceptive Threshold Mean ± SEM (seconds) |

GROUPS |

Nociceptive Threshold Mean ± SEM (seconds) |

|

Control (DN) |

4.2 ± 0.4 |

Control (DN) |

3.6 ± 0.2 |

|

EA 5 |

4.5 ± 0.2NS |

EA + Veh |

6.2 ± 0.2* |

|

EA 30 |

3.9 ± 0.3NS |

EA + Sac |

6.1 ± 0.2NS |

|

EA 100 |

6.8 ± 0.4* |

|

|

|

Control (DN) |

3.5 ± 0.2 |

Control (DN) |

3.8 ± 0.2 |

|

EA + Veh |

6.8 ± 0.5* |

EA + Veh |

6.6 ± 0.3* |

|

EA + Yoh 1 |

6.6 ± 0.6NS |

EA + Guv 20 |

5.9 ± 0.5NS |

|

EA + Yoh 2 |

5.8 ± 0.3NS |

EA + Guv 40 |

5.6 ± 0.4NS |

|

EA + Yoh 4 |

5.5 ± 0.4# |

EA + Guv 80 |

5.5 ± 0.3NS |

|

* Indicates a significant difference between the group that received EA (electroacupuncture) stimulation and the control group that received needling without stimulation (Dry Needle = DN). # Indicates a significant difference between the group EA treated with saclofen (Sac), yohimbine Yoh), or guvacine (Guv) and the group that received EA + Vehicle (Veh). NS: Not Significant. The nociceptive threshold was measured 15 minutes after EA stimulation. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test (n= 5). |

|||

Discussion

The question of whether acupuncture can effectively produce analgesia has received a positive response from the scientific literature. However, some meta-analytic studies suggest otherwise [17-19]. These authors raise concerns because most evaluated clinical studies have not utilized randomized, double-blind designs. A significant challenge in acupuncture research is establishing a reliable negative control group or placebo. To address this issue, some studies implement dry needling, where the acupuncture point is needled without stimulation [20]. Other researchers propose using sham acupuncture as a control, involving electrical stimulation applied to a needle inserted in a nearby region but not at the acupuncture point itself [21].

Recent research on the effects of acupuncture in animals strongly supports the idea that acupuncture can produce antinociception when combined with stimulation of specific points [22-23]. Furthermore, several studies have utilized advanced imaging techniques, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET), to evaluate how acupuncture activates related brain structures [24]. The findings indicate that when inhibitory pathways, such as those in the hypothalamus and brain stem (particularly the periaqueductal gray or PAG), are activated, there is a reduced activation in other areas, including the limbic system and amygdala. Therefore, it can now be considered a scientific fact that acupuncture has analgesic and antinociceptive effects.

The next step is to describe how acupuncture induces analgesia. Previous research has clarified several aspects of this process. Notably, early studies highlighted the ability of acupuncture to activate the opioidergic pathway [12,25,26]. This finding is further supported by research demonstrating the activation of opioidergic receptors in various supraspinal nuclei that play a role in the endogenous analgesic system [27].

The present study investigated the role of GABA and α2-adrenergic receptors in the analgesic effects of electroacupuncture (EA) on orofacial pain in rats, specifically by stimulating the ST36 acupuncture point. The analgesic effect induced by electroacupuncture was partially blocked by the systemic administration of the α2-adrenergic antagonist yohimbine, but not by the GABAB antagonist saclofen. These findings suggest that the analgesia produced by electroacupuncture is partially mediated through α2-adrenergic receptors rather than GABA.

Previous studies' findings regarding the effect of acupuncture on the noradrenergic pathway in achieving antinociception are highly controversial. Our study observed that the α2 receptor antagonist yohimbine reversed the antinociceptive effects of electroacupuncture (EA), but only at the beginning of the treatment. Given that the α2 receptor is activated by norepinephrine and is closely linked to the analgesic effects of this neurotransmitter, the results suggest that the noradrenergic pathway plays an initial role in the orofacial antinociception achieved through electroacupuncture at point ST36.

However, unlike the findings of this research, some studies suggest that acupuncture can more sustainably activate the noradrenergic pathway. This discrepancy may be attributed to certain methodological issues. Specifically, studies that reported positive outcomes for the noradrenergic pathway often utilized considerably high stimulus intensities, ranging from 2 to 20 mA, which is about 10 to 100 times greater than the tolerance threshold for the animal subjects involved [13,28].

In contrast, our study employed methods that closely resemble the clinical application of acupuncture and allowed for stimulation within a more appropriate range for the animals. We used a stimulation intensity of 0.5 mA, considered a sub-threshold for mice [13]. This difference in intensity may account for the varying results, as previous data from our group indicated that increasing the intensity above threshold levels can activate analgesic effects through pathways that are not triggered at sub-threshold levels.

Further comparative studies on stimulation intensities related to the other pathways investigated are needed to clarify this divergence more effectively. One study demonstrated that yohimbine inhibits the antinociceptive effects of acupuncture [11]. However, the observed antinociceptive action was attributed not to the acupuncture stimulation itself but rather to the application of bee venom at the ST36 point. In contrast, injecting a saline solution at the same point did not yield the same results. This indicates a clear difference in the stimulation methods, which may explain the discrepancies in the findings of the two studies.

Another study found that acupuncture at the ST36 point promoted antinociception alongside increased noradrenaline, histamine, and dopamine release in the ventrolateral region of the periaqueductal gray (PAG) [29]. However, this research lacks information on the intensity and frequency of stimulation, which hampers methodological comparisons with the current study. It has been established that modifications in these parameters can significantly influence the outcomes of experiments.

Despite the controversy surrounding this topic, some studies confirm these findings. One study involving trigeminal stimulation in rabbits found that acupuncture at a specific point can increase the animals' pain threshold. In this case, yohimbine was also unable to inhibit this increase in threshold [11].

Therefore, while further research is needed on this subject, it can be suggested that the noradrenergic pathway may play a role in the initial orofacial antinociception achieved through subthreshold stimulation of the acupuncture point ST36. Additionally, other systems, such as opioids, endocannabinoids, and nitric oxide, may contribute to the longer-lasting antinociceptive effects produced by electroacupuncture (EA), as demonstrated in our previous studies [7-9].

Our group has demonstrated that the trigeminal nociceptive pathway may be influenced by acupuncture through its ability to activate the nitric oxide, opioid, and endocannabinoid systems. However, it is known that other pathways are also involved in this endogenous antinociceptive system. Consequently, the present study investigated whether GABA could play a role in the electroacupuncture (EA)-induced antinociception associated with orofacial pain.

Few studies link acupuncture's effects to the modulation of the GABAergic pathway, and the situation is similar concerning acupuncture's antinociceptive action [14,30]. However, these studies primarily used animal models with inflammatory pathological conditions, such as arthritis and neuropathic pain induced by nerve ligation. The physiological response in a healthy animal differs significantly from that in an animal suffering from a pathological condition, which may explain the divergence in results.

To enhance our understanding of EA-induced analgesia, we conducted experiments to test the ability of EA at acupuncture point ST36 to activate the GABAergic pathway for achieving orofacial antinociception in rats. However, the results showed that neither the GABAB receptor antagonist saclofen nor the GABA reuptake inhibitor guvacine was able to alter the increase in the withdrawal threshold achieved through acupuncture.

Additionally, some studies suggest that acupuncture may reduce extracellular concentrations of GABA in the ventrolateral region of the globus pallidus, leading to cardiovascular changes through the activation of presynaptic CB1 cannabinoid receptors [31,32]. This could help explain the discrepancies observed in the findings. As demonstrated in our previous research [9], electroacupuncture (EA) can trigger a robust release of cannabinoids in central nervous system structures, including the hypothalamus and the periaqueductal gray (PAG), to produce antinociception. Suppose one of the cannabinoid actions in the PAG involves inhibiting the GABA pathway, as noted in the studies mentioned. In that case, evaluating the activation of this pathway becomes challenging, as it is inhibited by acupuncture through indirect processes involving endocannabinoids.

Conclusion

Based on the results obtained from our experiments and the findings reported in other studies on the subject, this study suggests that electroacupuncture at point ST36 is effective in producing orofacial antinociception in rats. The specific parameters used were a frequency of 100 Hz, an intensity of 0.5 mA, a pulse duration of 100 ms, and a stimulation time of 20 minutes.

While the involvement of several endogenous systems in this effect has been demonstrated, this study specifically showed the involvement of α2 adrenoceptors, and that GABA is not involved. Despite being the subject of limited research, the mechanisms behind acupuncture-induced analgesia remain poorly understood within the framework of modern science. Therefore, further studies are needed to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the action mechanisms of this ancient technique.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

2. Romero-Reyes M, Uyanik JM. Orofacial pain management: current perspectives. J Pain Res. 2014 Feb 21;7:99-115.

3. Hansen PE, Hansen JH. Acupuncture treatment of chronic facial pain--a controlled cross-over trial. Headache. 1983 Mar;23(2):66-9.

4. Goddard G. Short term pain reduction with acupuncture treatment for chronic orofacial pain patients. Med Sci Monit. 2005 Feb;11(2):CR71-4.

5. Smith P, Mosscrop D, Davies S, Sloan P, Al-Ani Z. The efficacy of acupuncture in the treatment of temporomandibular joint myofascial pain: a randomised controlled trial. J Dent. 2007 Mar;35(3):259-67.

6. Wang W, Liu L, Zhi X, Huang JB, Liu DX, Wang H, et al. Study on the regulatory effect of electro-acupuncture on hegu point (LI4) in cerebral response with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Chin J Integr Med. 2007 Mar;13(1):10-6.

7. Almeida RT, Perez AC, Francischi JN, Castro MS, Duarte ID. Opioidergic orofacial antinociception induced by electroacupuncture at acupoint St36. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2008 Jul;41(7):621-6.

8. Almeida RT, Duarte ID. Nitric oxide/cGMP pathway mediates orofacial antinociception induced by electroacupuncture at the St36 acupoint. Brain Res. 2008 Jan 10;1188:54-60.

9. Almeida RT, Romero TR, Romero MG, de Souza GG, Perez AC, Duarte ID. Endocannabinoid mechanism for orofacial antinociception induced by electroacupuncture in acupoint St36 in rats. Pharmacol Rep. 2016 Dec;68(6):1095-101.

10. Szabadi E. Modulation of physiological reflexes by pain: role of the locus coeruleus. Front Integr Neurosci. 2012 Oct 17;6:94-109.

11. Takagi J, Sawada T, Yonehara N. A possible involvement of monoaminergic and opioidergic systems in the analgesia induced by electro-acupuncture in rabbits. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1996 Jan;70(1):73-80.

12. Baek YH, Huh JE, Lee JD, Choi DY, Park DS. Antinociceptive effect and the mechanism of bee venom acupuncture (Apipuncture) on inflammatory pain in the rat model of collagen-induced arthritis: Mediation by alpha2-Adrenoceptors. Brain Res. 2006 Feb 16;1073-1074:305-10.

13. Koo ST, Lim KS, Chung K, Ju H, Chung JM. Electroacupuncture-induced analgesia in a rat model of ankle sprain pain is mediated by spinal alpha-adrenoceptors. Pain. 2008 Mar;135(1-2):11-9.

14. Park JH, Han JB, Kim SK, Park JH, Go DH, Sun B, et al. Spinal GABA receptors mediate the suppressive effect of electroacupuncture on cold allodynia in rats. Brain Res. 2010 Mar 31;1322:24-9.

15. de Medeiros MA, Canteras NS, Suchecki D, Mello LE. Analgesia and c-Fos expression in the periaqueductal gray induced by electroacupuncture at the Zusanli point in rats. Brain Res. 2003 May 30;973(2):196-204.

16. Medeiros MA, Canteras NS, Suchecki D, Mello LE. c-Fos expression induced by electroacupuncture at the Zusanli point in rats submitted to repeated immobilization. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003 Dec;36(12):1673-84.

17. Rosted P. Practical recommendations for the use of acupuncture in the treatment of temporomandibular disorders based on the outcome of published controlled studies. Oral Dis. 2001 Mar;7(2):109-15.

18. Ezzo J, Berman B, Hadhazy VA, Jadad AR, Lao L, Singh BB. Is acupuncture effective for the treatment of chronic pain? A systematic review. Pain. 2000 Jun;86(3):217-25.

19. White A, Trinh K, Hammerschlag R. Performing systematic reviews of clinical trials of acupuncture: problems and solutions. Clinical Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine. 2002 Mar 1;3(1):26-31.

20. Knardahl S, Elam M, Olausson B, Wallin GB. Sympathetic nerve activity after acupuncture in humans. Pain. 1998 Mar;75(1):19-25.

21. Xue CC, Dong L, Polus B, English RA, Zheng Z, Da Costa C, et al. Electroacupuncture for tension-type headache on distal acupoints only: a randomized, controlled, crossover trial. Headache. 2004 Apr;44(4):333-41.

22. Chen JX, Ma SX. Effects of nitric oxide and noradrenergic function on skin electric resistance of acupoints and meridians. J Altern Complement Med. 2005 Jun;11(3):423-31.

23. Ceccherelli F, Gagliardi G, Ruzzante L, Giron G. Acupuncture modulation of capsaicin-induced inflammation: effect of intraperitoneal and local administration of naloxone in rats. A blinded controlled study. J Altern Complement Med. 2002 Jun;8(3):341-9.

24. Hsieh CL, Chang QY, Lin IH, Lin JG, Liu CH, Tang NY, et al. The study of electroacupuncture on cerebral blood flow in rats with and without cerebral ischemia. Am J Chin Med. 2006;34(2):351-61.

25. Han JS, Li SJ, Tang J. Tolerance to electroacupuncture and its cross tolerance to morphine. Neuropharmacology. 1981 Jun;20(6):593-6.

26. Huang C, Wang Y, Han JS, Wan Y. Characteristics of electroacupuncture-induced analgesia in mice: variation with strain, frequency, intensity and opioid involvement. Brain Res. 2002 Jul 26;945(1):20-5.

27. Ma SX. Neurobiology of Acupuncture: Toward CAM. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2004 Jun 1;1(1):41-47.

28. Yang CH, Lee BB, Jung HS, Shim I, Roh PU, Golden GT. Effect of electroacupuncture on response to immobilization stress. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002 Jul;72(4):847-55.

29. Murotani T, Ishizuka T, Nakazawa H, Wang X, Mori K, Sasaki K, et al. Possible involvement of histamine, dopamine, and noradrenalin in the periaqueductal gray in electroacupuncture pain relief. Brain Res. 2010 Jan 8;1306:62-8.

30. Cao X. Scientific bases of acupuncture analgesia. Acupunct Electrother Res. 2002;27(1):1-14.

31. Fu LW, Longhurst JC. Electroacupuncture modulates vlPAG release of GABA through presynaptic cannabinoid CB1 receptors. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2009 Jun;106(6):1800-9.

32. Tjen-A-Looi SC, Li P, Longhurst JC. Processing cardiovascular information in the vlPAG during electroacupuncture in rats: roles of endocannabinoids and GABA. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2009 Jun;106(6):1793-9.