Abstract

Angiotensin-(1-7) [Ang-(1-7)] is a biologically active peptide of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) that counterbalances the actions of angiotensin II (Ang II), primarily through binding to the Mas receptor (MasR). This axis exerts significant immunomodulatory effects by influencing several features of leukocytes, including macrophage function, a central component in the resolution of inflammation. Macrophages contribute to tissue homeostasis by clearing apoptotic cells, releasing anti-inflammatory mediators and supporting tissue repair. Herein, we highlight the evidence supporting the role of Ang-(1-7) in guiding macrophages toward inflammation resolution. In this context, Ang-(1-7)/MasR signaling has been shown to induce several functions in macrophages, including suppression of pro-inflammatory activity, enhancement of apoptotic cells efferocytosis and bacterial phagocytosis, and promotion of macrophage polarization toward regulatory phenotypes.

Keywords

Macrophages, Mas receptor (MasR), Ang-(1-7), Inflammation resolution, Efferocytosis

Abbreviations

Ang-(1-7): Angiotensin-(1-7); MasR: Mas receptor; SPMs: Specialized Proresolving Mediators; PMN: Polymorphonuclear Neutrophils; M1: Classically Activated Macrophages; M2: Alternatively Activated Macrophages; Mres: Proresolving Macrophages; TGF-β: Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β); IL: Interleukin; CCR: C-C Motif Chemokine Receptor; CCL: C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand; MEK/ERK: Mitogen-activated Protein Kinases; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide

Angiotensin-(1-7) Production and Action

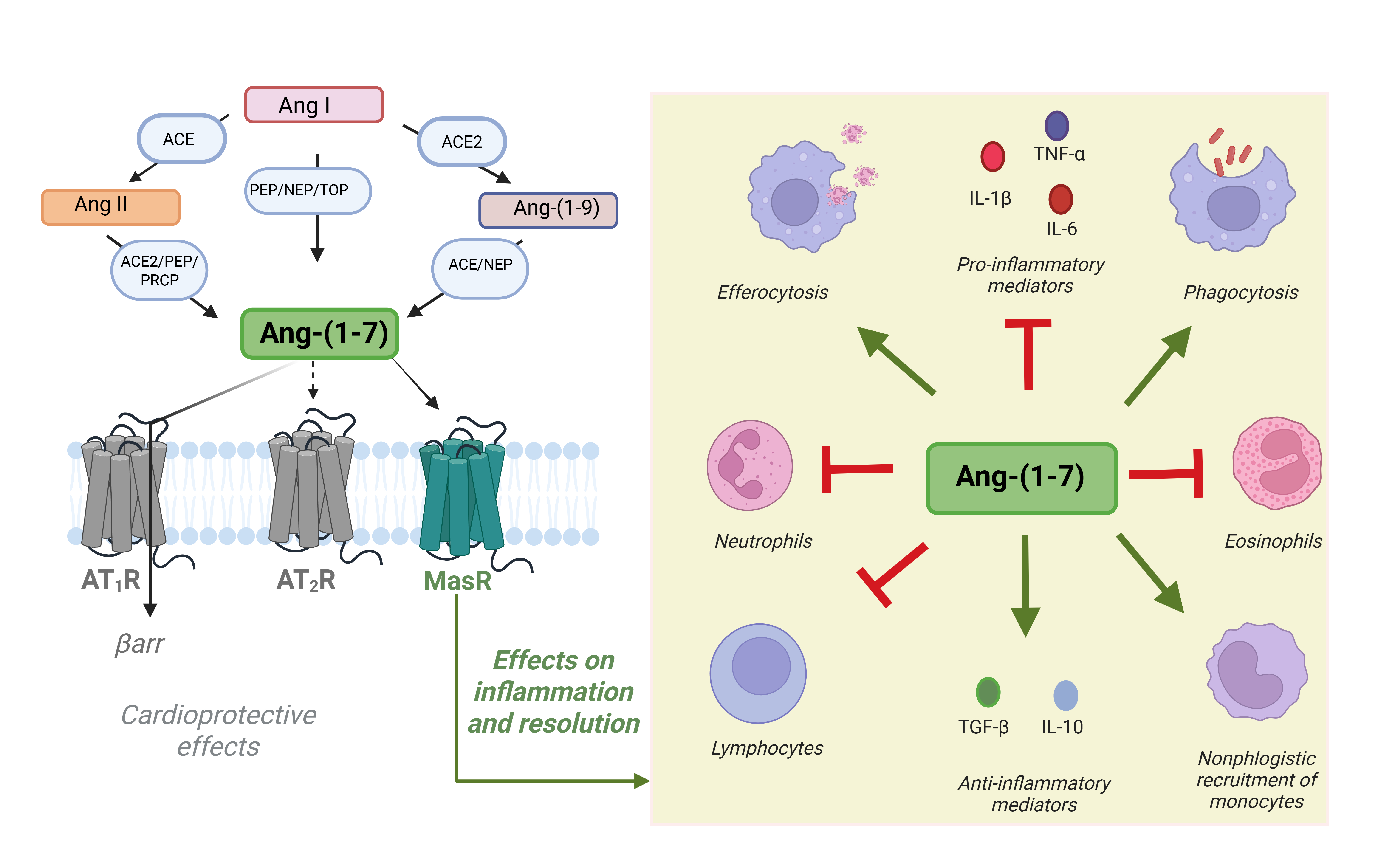

Angiotensin-(1-7) [Ang-(1-7)] is a bioactive component of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) that counteracts the actions of angiotensin II (Ang II) by exerting vasodilatory, anti-inflammatory [1], antifibrotic [2,3], and tissue-protective effects [4]. Ang-(1-7) is generated from Ang I through neprilysin (NEP), prolylendopeptidase (PEP), or thimet oligopeptidase (TOP) activity; from Ang II via angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), prolylcarboxypeptidase (PRCP), or prolylendopeptidase (PEP); and from Ang-(1-9) through ACE or NEP, as shown in Figure 1 [5–8].

The autocrine and paracrine effects of Ang-(1-7) are mainly mediated by the G protein–coupled receptor Mas (MasR) [9], which is expressed in various tissues, including the heart, brain, kidney, and lungs [10], as well as in immune cells such as macrophages [11–13]. By interacting with MasR, Ang-(1-7) has been shown to decrease infiltration of neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes, thereby reducing tissue damage caused by excessive inflammation in preclinical models of arthritis [14], asthma [15,16], pulmonary fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and acute lung injury [17,18], ischemic stroke [19], ultimately preventing several features of inflammation [11,20]. Interestingly, a single dose of Ang-(1-7) promotes lung inflammation resolution and provides lasting protection against secondary challenges with allergens or endotoxin by enhancing IL-10, regulatory T cells, and macrophage efferocytosis [18].

Ang-(1-7) exhibits anti-inflammatory effects primarily by suppressing the release of key pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [11,21], and by limiting the migration and activation of inflammatory cells [14,22]. It also promotes the generation of nitric oxide (NO) [23] and anti-inflammatory prostanoids [24], contributing to the maintenance of tissue homeostasis. Beyond anti-inflammatory actions, Ang-(1-7) displays pro-resolving properties. It enhances efferocytosis [25] and phagocytic clearance of apoptotic neutrophils, favors macrophage reprogramming toward a regulatory phenotype [13], and helps terminate inflammation. Furthermore, Ang-(1-7) reduces fibroblast activation and pathological extracellular matrix accumulation, thereby preventing fibrosis [26,27]. Lipoxin A4, a specialized pro-resolving mediator (SPM), has been shown to upregulate elements of the Ang-(1-7) axis—including ACE2, Ang-(1-7), and the Mas receptor—particularly in models of lung injury [28].

The Role of Macrophages in Inflammation and Resolution

Inflammation occurs in vascularized tissues after injury or infection and is characterized by edema and arrival of leukocytes to the damage site or bacterial entry point. This vital host defense mechanism helps eliminate pathogens effectively and supports tissue repair, ultimately restoring organ and tissue function [29,30]. Concomitantly, affected tissue shows decreased synthesis and enhanced catabolism of pro-inflammatory mediators, while generation and release of anti-inflammatory and proresolving mediators rise, providing the stage for the resolution of inflammation [31–33,34].

Resolution of inflammation is an active, tightly regulated process through which the organism actively ends the inflammatory response, restores homeostatic conditions, and begins repairing affected tissues [33,35]. Key steps for proper resolution of inflammation involve activation of several mediators and cellular processes that collectively drive the swift and complete restoration of tissue homeostasis, such as elimination of inciting stimulus, cessation of PMN influx, catabolism of proinflammatory mediators, PMN apoptosis, efferocytosis, non-phlogistic macrophage recruitment, macrophage phenotype reprogramming (from M1 to M2, and from M2 to Mres), and production of anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving mediators. For comprehensive reviews, see [1,33,36,37].

Seminal research by Elie Metchnikoff established the important role of macrophages in coordinating the host immune response [38,39]. Macrophages are essential for clearing pathogen and cellular debris from inflammatory sites and also aid resolve inflammation promoting tissue repair and regeneration [40]. Indeed, the role of macrophage in cleaning debris generated by cell death during inflammatory injury, which can promote immune cell activation amplifying the inflammatory response, is critical for maintenance of tissue integrity and avoidance of tissue self-harm [41,42].

The recruitment of macrophages is a hallmark of the resolution phase of acute inflammation with their numbers increasing in tissue in parallel with the drop of neutrophils [13,43,44], underscoring the key role of macrophage in clearing dead cells. In the resolution phase of acute inflammation a specific subset of macrophages emerges, playing a crucial role in restoring homeostasis by initiating the removal of apoptotic leukocytes through efferocytosis [45–47]. Notably, efferocytosis induces a functional rewiring of macrophage toward anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving profiles [48,49].

Although the classification of macrophage phenotypes has modified and grown in complexity significantly in recent years, traditionally, macrophages are classified into M1 (classical activation, involved in the beginning of inflammation) and M2 (alternative activation, anti-inflammatory) [50]. A so-called Mres or pro-resolving group of macrophages (endowed with tissue remodeling properties) has been identified at sites of inflammation during the resolution phase [43,48,49]. Whereas M2 IL-10-producing macrophages are known to be highly efferocytic and help resolve inflammation [51], Mres macrophages are described as satiated and poor efferocytic [48,49]. More recently, a new group of macrophages—named rejuvenated hyper-efferocytic Ly6C+ macrophages—has been described and shown to be induced by IFN-β and to display enhanced efferocytic capacity via high CD36 receptor expression [52]. Overall, the arrival of macrophages with pro-resolving profiles promoting clearance of apoptotic death cells and debris, releasing anti-inflammatory/pro-resolving mediators, and promoting tissue repair/regeneration is crucial for termination of the inflammatory response and restoration of homeostasis.

Effects of Angiotensin- (1-7) on Macrophages

Groundbreaking research over the past few decades by various laboratories worldwide has revealed the anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving effects of Ang-(1-7) [1–3,11,13,14,16,20,21,25,53–57]. These biological actions of Ang-(1-7) are mediated through its interaction with the MasR [9], a receptor found in leukocytes, including macrophage [12,13] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Biosynthesis of Ang-(1-7) and its effects on inflammation and resolution. Ang-(1-7) can be produced from Ang I, Ang II, or Ang-(1-9) through enzymatic cleavage by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), ACE2, neprilysin (NEP), prolylendopeptidase (PEP), prolylcarboxypeptidase (PRCP), and thimet oligopeptidase (TOP). Once formed, Ang-(1-7) binds primarily to the Mas receptor (MasR), and to a lesser extent to AT2R, exerting protective effects on inflammation and its resolution. Ang-(1-7) can also act as an endogenous β-arrestin-biased agonist at the AT1R, causing cardioprotective effects without engaging its canonical G protein signaling pathway. Through MasR signaling, Ang-(1-7) enhances macrophage efferocytosis and phagocytosis, promotes production of anti-inflammatory mediators (TGF-β, IL-10), and facilitates non-phlogistic recruitment of monocytes. Simultaneously, it suppresses neutrophil activation, eosinophil responses, lymphocyte-driven inflammation, and reduces secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6). Collectively, these actions establish Ang-(1-7) as a key regulator of immune balance and tissue homeostasis. Created in BioRender.

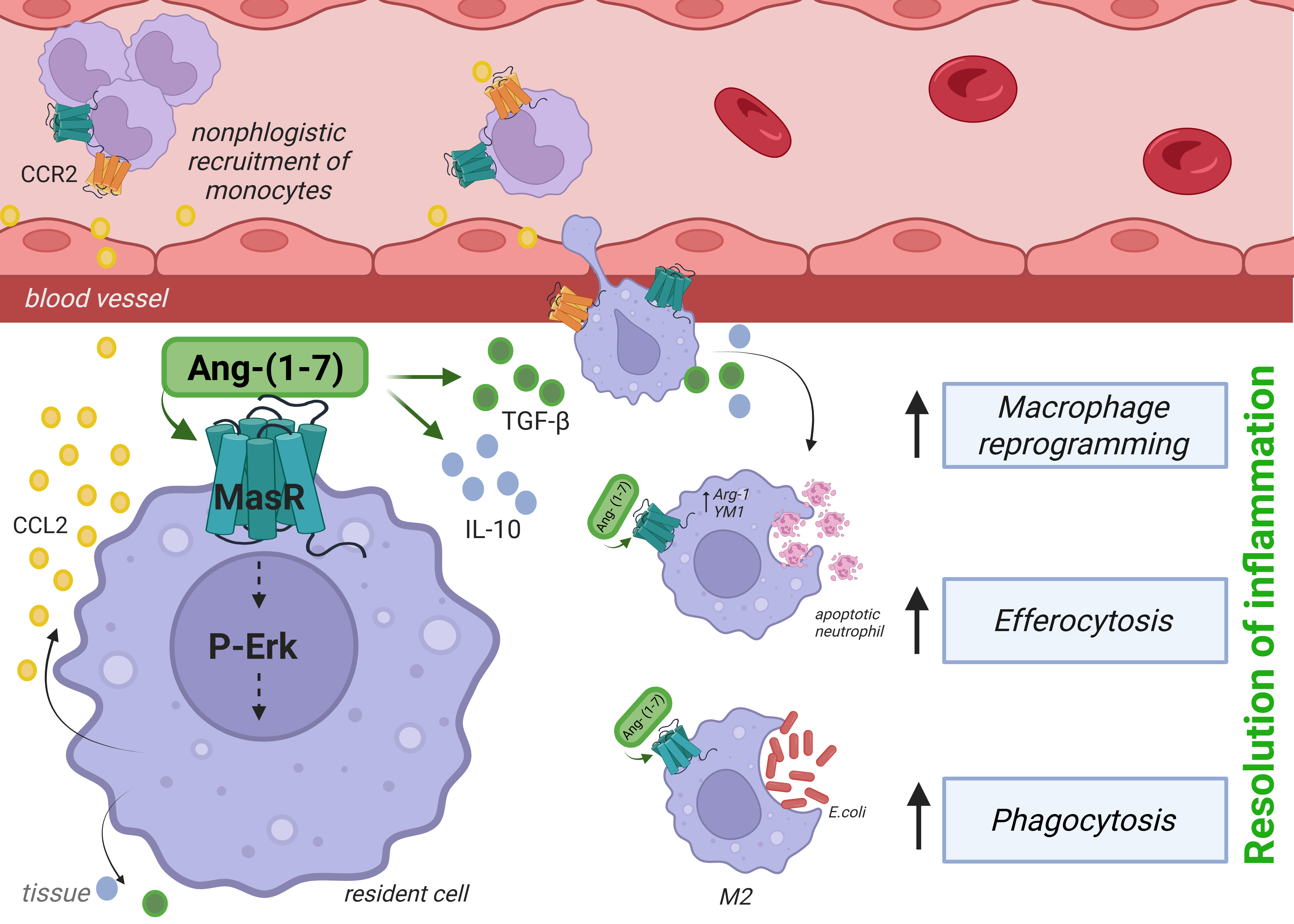

Several studies have demonstrated that the Ang-(1-7)/MasR axis inhibits the ability of macrophages to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines [11,12,21,22]. Additionally, Ang-(1-7) increases the efferocytic ability of macrophages to clean up apoptotic neutrophils [13,25,54,56] and eosinophils [16] within inflammatory sites. In this commentary, we analyze the study by Zaidan et al. [13]. Using self-resolving models of acute inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and Escherichia coli, the research group led by Sousa and Teixeira [13] employed both pharmacological tools and MasR knockout mice (MasR- /-) to show that Ang-(1-7) signaling promoted nonphlogistic migration of macrophage and their further polarization toward regulatory phenotypes (M2 and Mres). Ang-(1-7) enhanced efferocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils and phagocytosis of E. coli and facilitated the resolution of inflammation, actions that occurred via MasR. The authors also examined the underlying mechanisms, demonstrating that Ang-(1-7) stimulated cell migration though a CCL2/CCR2 sensitive pathway. In addition, these macrophages expressed Arginase-1 and YM1 (classical M2 markers) and released IL-10 and TGF-β, as represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Ang-(1-7) promotes resolution of inflammation through Mas receptor (MasR) signaling in macrophages. Binding of Ang-(1-7) to MasR activates ERK1/2 phosphorylation and induces CCL2 production, leading to nonphlogistic recruitment of monocytes via CCR2. MasR signaling enhances the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines (TGF-β, IL-10) and stimulates macrophage effector functions, including efferocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils and phagocytosis of pathogens, thereby driving inflammation resolution and tissue repair. Created in BioRender.

Ang-(1-7) itself promoted chemotaxis of murine and human macrophages, but had no direct effect on the chemotaxis of neutrophils. In contrast, Ang-(1-7) inhibited chemotaxis of neutrophils toward fMLP and also decreased chemotaxis of macrophages toward LPS. The latter findings are in agreement with others showing that Ang-(1-7) could deactivate several pro-inflammatory functions of macrophages [11,22,58,59]. A recent study showed that Ang-(1-7) modulated the Warburg effect via the citrate pathway in LPS-stimulated macrophages and reduced inflammation and organ damage in septic mice [60].

In vivo injection of Ang-(1-7) in the plural cavity of mice promoted selective migration of monocytes/macrophages in a MasR- and the CCR2-dependent manner. Importantly, Ang-(1-7) activated the MEK/ERK1/2 pathway, leading to CCL2 production and further recruitment of mononuclear cells via CCR2 (Figure 2). Of Note, the chemokine CCL2 has been shown to promote M2 polarization [44,61–63] and macrophage-mediated clearance of apoptotic cells [64], actions needed for effective resolution of inflammation. Although CCR2 and MasR were co-expressed and needed for Ang-(1-7)-induced macrophage migration, the study did not establish whether Ang-(1-7) directly or indirectly interacted with CCR2 to drive chemotaxis, highlighting the need for further research to clarify these mechanisms.

In addition to showing that Ang-(1-7) could alter macrophage function to induce resolution of inflammation in response to LPS, the authors also showed that Ang-(1-7)- exposed macrophages could significantly increase E. coli engulfment and clearance. The latter effects could explain the decreased ability of MasR deficient mice to deal with infection. A recent study has shown that myeloid-specific MasR deficiency impairs efferocytosis and hampers inflammation resolution [47]. The loss of MasR reduced MERTK expression—a receptor essential for apoptotic cell clearance—thereby limiting macrophage-mediated removal of apoptotic neutrophils. Together with the findings of Zaidan et al. [13], these results underscore MasR signaling as a central regulator of efferocytosis and inflammation resolution. Of interest, follow up studies in our lab have extended these observations and shown Ang-(1-7)/MasR can promote phagocytosis and clearance of other bacteria, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa [56] and Streptococcus pneumonia [65].

Conclusion and Perspectives

In summary, the study by Zaidan et al. [13] addresses a key gap in our understanding of the Ang-(1-7)/MasR axis in macrophage-driven processes vital for resolving inflammation. These processes include the recruitment of macrophage endowed with a regulatory phenotype promoting clearance of apoptotic neutrophils and bacteria. The study also indicates that Ang-(1-7) improves macrophage antimicrobial functions while preventing excessive inflammation—an important feature with clear clinical implications for infection management—suggesting that combined treatment of Ang-(1-7) with antibiotics would improve bacterial resistance and resilience during infectious diseases. Indeed, adjunctive treatment with Ang-(1-7) and antibiotics during pneumonia induced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa [56] or Streptococcus pneumonia [65] improves the phagocytic ability of macrophages resulting in enhanced bacterial clearance and mice survival. In addition to altering the pathogenesis of bacterial infections, our group has also demonstrated that treatment with Ang-(1-7) lessened inflammation and lung injury caused by influenza and SARS-CoV-2 [54,57,66]. Additional insights into the therapeutic potential of Ang-(1-7) in infectious diseases can be found in Tavares et al. [1] and Costa et al, [34].

Finally, although we have learned a great deal about the crucial role of MasR and beneficial functions of Ang-(1-7) in the context of inflammatory and infectious diseases, there is much to learn about the detailed signaling mechanisms triggered by MasR signaling. This knowledge will be crucial to generate better molecules to be used in humans.

Conflict of Interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was was supported by grants from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG, BPD-01010-22) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, 310799/2022-8 and 303068/2024-8). This work also received financial support from the National Institute of Science and Technology in Dengue and Host-Microorganism Interaction (INCT in Dengue), a program grant sponsored CNPq and FAPEMIG (Grant numbers 465425/2014-3 and 408527/2024-2).

References

2. Simões e Silva AC, Silveira KD, Ferreira AJ, Teixeira MM. ACE2, angiotensin-(1-7) and Mas receptor axis in inflammation and fibrosis. Br J Pharmacol. 2013 Jun;169(3):477–92.

3. Simões E Silva AC, Teixeira MM. ACE inhibition, ACE2 and angiotensin-(1-7) axis in kidney and cardiac inflammation and fibrosis. Pharmacol Res. 2016 May;107:154–62.

4. Ferrario CM, Iyer SN. Angiotensin-(1-7): a bioactive fragment of the renin-angiotensin system. Regul Pept. 1998 Nov 30;78(1-3):13–8.

5. Vickers C, Hales P, Kaushik V, Dick L, Gavin J, Tang J, et al. Hydrolysis of biological peptides by human angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem. 2002 Apr 26;277(17):14838–43.

6. Zisman LS, Keller RS, Weaver B, Lin Q, Speth R, Bristow MR, et al. Increased angiotensin-(1-7)-forming activity in failing human heart ventricles: evidence for upregulation of the angiotensin-converting enzyme Homologue ACE2. Circulation. 2003 Oct 7;108(14):1707–12.

7. Teixeira LB, Parreiras-E-Silva LT, Bruder-Nascimento T, Duarte DA, Simões SC, Costa RM, et al. Ang-(1-7) is an endogenous β-arrestin-biased agonist of the AT1 receptor with protective action in cardiac hypertrophy. Sci Rep. 2017 Sep 19;7(1):11903.

8. Bader M, Steckelings UM, Alenina N, Santos RAS, Ferrario CM. Alternative Renin-Angiotensin System. Hypertension. 2024 May;81(5):964–76.

9. Santos RA, Simoes e Silva AC, Maric C, Silva DM, Machado RP, de Buhr I, et al. Angiotensin-(1-7) is an endogenous ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor Mas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Jul 8;100(14):8258–63.

10. Santos RAS, Sampaio WO, Alzamora AC, Motta-Santos D, Alenina N, Bader M, et al. The ACE2/Angiotensin-(1-7)/MAS Axis of the Renin-Angiotensin System: Focus on Angiotensin-(1-7). Physiol Rev. 2018 Jan 1;98(1):505–53.

11. Liu M, Shi P, Sumners C. Direct anti-inflammatory effects of angiotensin-(1-7) on microglia. J Neurochem. 2016 Jan;136(1):163–71.

12. Hammer A, Yang G, Friedrich J, Kovacs A, Lee DH, Grave K, et al. Role of the receptor Mas in macrophage-mediated inflammation in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 Dec 6;113(49):14109–14.

13. Zaidan I, Tavares LP, Sugimoto MA, Lima KM, Negreiros-Lima GL, Teixeira LC, et al. Angiotensin-(1-7)/MasR axis promotes migration of monocytes/macrophages with a regulatory phenotype to perform phagocytosis and efferocytosis. JCI Insight. 2022 Jan 11;7(1):e147819.

14. da Silveira KD, Coelho FM, Vieira AT, Sachs D, Barroso LC, Costa VV, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of the activation of the angiotensin-(1-7) receptor, MAS, in experimental models of arthritis. J Immunol. 2010 Nov 1;185(9):5569–76.

15. El-Hashim AZ, Renno WM, Raghupathy R, Abduo HT, Akhtar S, Benter IF. Angiotensin-(1-7) inhibits allergic inflammation, via the MAS1 receptor, through suppression of ERK1/2- and NF-κB-dependent pathways. Br J Pharmacol. 2012 Jul;166(6):1964–76.

16. Magalhaes GS, Barroso LC, Reis AC, Rodrigues-Machado MG, Gregório JF, Motta-Santos D, et al. Angiotensin-(1-7) Promotes Resolution of Eosinophilic Inflammation in an Experimental Model of Asthma. Front Immunol. 2018 Jan 29;9:58.

17. Gan PXL, Liao W, Linke KM, Mei D, Wu XD, Wong WSF. Targeting the renin angiotensin system for respiratory diseases. Adv Pharmacol. 2023;98:111–44.

18. Magalhaes GS, Gregorio JF, Beltrami VA, Felix FB, Oliveira-Campos L, Bonilha CS, et al. A single dose of angiotensin-(1-7) resolves eosinophilic inflammation and protects the lungs from a secondary inflammatory challenge. Inflamm Res. 2024 Jun;73(6):1019–31.

19. Regenhardt RW, Desland F, Mecca AP, Pioquinto DJ, Afzal A, Mocco J, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of angiotensin-(1-7) in ischemic stroke. Neuropharmacology. 2013 Aug;71:154–63.

20. Khajah MA, Fateel MM, Ananthalakshmi KV, Luqmani YA. Anti-Inflammatory Action of Angiotensin 1-7 in Experimental Colitis. PLoS One. 2016 Mar 10;11(3):e0150861.

21. Souza LL, Costa-Neto CM. Angiotensin-(1-7) decreases LPS-induced inflammatory response in macrophages. J Cell Physiol. 2012 May;227(5):2117–22.

22. de Carvalho Santuchi M, Dutra MF, Vago JP, Lima KM, Galvão I, de Souza-Neto FP, et al. Angiotensin-(1-7) and Alamandine Promote Anti-inflammatory Response in Macrophages In Vitro and In Vivo. Mediators Inflamm. 2019 Feb 21;2019:2401081.

23. Pörsti I, Bara AT, Busse R, Hecker M. Release of nitric oxide by angiotensin-(1-7) from porcine coronary endothelium: implications for a novel angiotensin receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 1994 Mar;111(3):652–4.

24. Jaiswal N, Diz DI, Chappell MC, Khosla MC, Ferrario CM. Stimulation of endothelial cell prostaglandin production by angiotensin peptides: characterization of receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265(2):664–75.

25. Barroso LC, Magalhaes GS, Galvão I, Reis AC, Souza DG, Sousa LP, et al. Angiotensin-(1-7) Promotes Resolution of Neutrophilic Inflammation in a Model of Antigen-Induced Arthritis in Mice. Front Immunol. 2017 Nov 20;8:1596.

26. Grobe JL, Mecca AP, Lingis M, Shenoy V, Bolton TA, Machado JM, et al. Chronic angiotensin-(1-7) prevents cardiac fibrosis in DOCA-salt model of hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290(6):H2417–23.

27. Papinska AM, Soto M, Meeks CJ, Rodgers KE. Long-term administration of angiotensin (1-7) prevents heart and lung dysfunction in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes (db/db) by reducing oxidative stress, inflammation and pathological remodeling. Pharmacol Res. 2016 May;107:372–80.

28. Chen QF, Kuang XD, Yuan QF, Hao H, Zhang T, Huang YH, Zhou XY. Lipoxin A4 attenuates LPS-induced acute lung injury via activation of the ACE2-Ang-(1-7)-Mas axis. Innate Immun. 2018 Jul;24(5):285–96.

29. Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature. 2008 Jul 24;454(7203):428–35.

30. Menezes GB, Mansur DS, McDonald B, Kubes P, Teixeira MM. Sensing sterile injury: opportunities for pharmacological control. Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Nov;132(2):204–14.

31. Serhan CN, Savill J. Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat Immunol. 2005 Dec;6(12):1191–7.

32. Sugimoto MA, Vago JP, Teixeira MM, Sousa LP. Annexin A1 and the resolution of inflammation: modulation of neutrophil recruitment, apoptosis, and clearance. Blood. 2017;129(14):1846–55.

33. Sugimoto MA, Vago JP, Perretti M, Teixeira MM. Mediators of the Resolution of the Inflammatory Response. Trends Immunol. 2019 Mar;40(3):212–27.

34. Costa VV, Resende F, Melo EM, Teixeira MM. Resolution pharmacology and the treatment of infectious diseases. Br J Pharmacol. 2024 Apr;181(7):917–37.

35. Serhan CN. The resolution of inflammation: the devil in the flask and in the details. FASEB J. 2011 May;25(5):1441–8.

36. Panigrahy D, Gilligan MM, Serhan CN, Kashfi K. Resolution of inflammation: An organizing principle in biology and medicine. Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Nov;227:107879.

37. Ortega-Gómez A, Perretti M, Soehnlein O. Resolution of inflammation: an integrated view. EMBO Mol Med. 2013 May;5(5):661–74.

38. Metschnikoff E. Über die intracelluläre Verdauung bei Coelenteraten. Zool. Anz.1880;3(56):261–3.

39. Tauber AI, Chernyak L. Metchnikoff and the origins of immunology: From metaphor to theory. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991.

40. Dalli J, Serhan CN. Pro-resolving mediators in regulating and conferring macrophage function. Frontiers in immunology. 2017 Nov 1;8:1400.

41. Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Konowal A, Freed PW, Westcott JY, Henson PM. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-beta, PGE2, and PAF. J Clin Invest. 1998 Feb 15;101(4):890–8.

42. Chakraborty S, Singh A, Wang L, Wang X, Sanborn MA, Ye Z, et al. Trained immunity of alveolar macrophages enhances injury resolution via KLF4-MERTK-mediated efferocytosis. J Exp Med. 2023 Nov 6;220(11):e20221388.

43. Vago JP, Tavares LP, Garcia CC, Lima KM, Perucci LO, Vieira ÉL, et al. The role and effects of glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper in the context of inflammation resolution. J Immunol. 2015 May 15;194(10):4940-50.

44. Negreiros-Lima GL, Lima KM, Moreira IZ, Jardim BLO, Vago JP, Galvão I, et al. Cyclic AMP regulates key features of macrophages via PKA: recruitment, reprogramming and efferocytosis. Cells. 2020;9(1):128.

45. Stables MJ, Shah S, Camon EB, Lovering RC, Newson J, Bystrom J, et al. Transcriptomic analyses of murine resolution-phase macrophages. Blood. 2011 Dec 22;118(26):e192–208.

46. Alessandri AL, Sousa LP, Lucas CD, Rossi AG, Pinho V, Teixeira MM. Resolution of inflammation: mechanisms and opportunity for drug development. Pharmacol Ther. 2013 Aug;139(2):189–212.

47. Chen S, Huang B, Li S, Wang Z, Chang Y, Huang H, et al. Myeloid MAS–driven macrophage efferocytosis promotes resolution in ischemia-stressed mouse and human livers. Science Translational Medicine. 2025 Jul 9;17(806):eadr2725.

48. Ariel A, Serhan CN. New Lives Given by Cell Death: Macrophage Differentiation Following Their Encounter with Apoptotic Leukocytes during the Resolution of Inflammation. Front Immunol. 2012 Jan 31;3:4.

49. Schif-Zuck S, Gross N, Assi S, Rostoker R, Serhan CN, Ariel A. Saturated-efferocytosis generates pro-resolving CD11b low macrophages: modulation by resolvins and glucocorticoids. Eur J Immunol. 2011 Feb;41(2):366–79.

50. Mills CD, Kincaid K, Alt JM, Heilman MJ, Hill AM. M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. J Immunol. 2000 Jun 15;164(12):6166–73.

51. Xu W, Roos A, Schlagwein N, Woltman AM, Daha MR, van Kooten C. IL-10-producing macrophages preferentially clear early apoptotic cells. Blood. 2006 Jun 15;107(12):4930–7.

52. Zeituni-Timor O, Soboh S, Zaid A, Yaseen H, Kumaran Satyanarayanan S, Abu Zeid M, et al. IFN-β and ARTS deficiency promote the generation of hyper-efferocytic Ly6C+ macrophages in resolving inflammation in male mice. Commun Biol. 2025 Aug 23;8(1):1269.

53. Collins KL, Younis US, Tanyaratsrisakul S, Polt R, Hay M, Mansour HM, Ledford JG. Angiotensin-(1–7) peptide hormone reduces inflammation and pathogen burden during mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in mice. Pharmaceutics. 2021 Oct 4;13(10):1614.

54. Melo EM, Del Sarto J, Vago JP, Tavares LP, Rago F, Gonçalves AP, et al. Relevance of angiotensin-(1-7) and its receptor Mas in pneumonia caused by influenza virus and post-influenza pneumococcal infection. Pharmacological research. 2021 Jan 1;163:105292.

55. Shen YL, Hsieh YA, Hu PW, Lo PC, Hsiao YH, Ko HK, et al. Angiotensin-(1–7) attenuates SARS-CoV2 spike protein-induced interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 production in alveolar epithelial cells through activation of Mas receptor. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection. 2023 Dec 1;56(6):1147–57.

56. Zaidan I, Carvalho AF, Grossi LC, Souza JA, Lara ES, Montuori‐Andrade AC, et al. The angiotensin‐(1‐7)/MasR axis improves pneumonia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Extending the therapeutic window for antibiotic therapy. The FASEB Journal. 2024 Sep 30;38(18):e70051.

57. Lima EBS, Carvalho AFS, Zaidan I, Monteiro AHA, Cardoso C, et al. Angiotensin-(1-7) decreases inflammation and lung damage caused by betacoronavirus infection in mice. Inflamm Res. 2024 Nov;73(11):2009–202.

58. Yang J, Sun Y, Dong M, Yang X, Meng X, Niu R, et al. Comparison of angiotensin-(1-7), losartan and their combination on atherosclerotic plaque formation in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Atherosclerosis. 2015 Jun;240(2):544–9.

59. Skiba DS, Nosalski R, Mikolajczyk TP, Siedlinski M, Rios FJ, Montezano AC, et al. Anti-atherosclerotic effect of the angiotensin 1-7 mimetic AVE0991 is mediated by inhibition of perivascular and plaque inflammation in early atherosclerosis. Br J Pharmacol. 2017 Nov;174(22):4055–69.

60. Yu D, Huang W, Sheng M, Zhang S, Pan H, Ren F, Luo L, Zhou J, Huang D, Tang L. Angiotensin-(1-7) Modulates the Warburg Effect to Alleviate Inflammation in LPS-Induced Macrophages and Septic Mice. J Inflamm Res. 2024 Jan 24;17:469–85.

61. Farro G, Stakenborg M, Gomez-Pinilla PJ, Labeeuw E, Goverse G, Di Giovangiulio M, et al. CCR2-dependent monocyte-derived macrophages resolve inflammation and restore gut motility in postoperative ileus. Gut. 2017 Dec;66(12):2098–109.

62. Roca H, Varsos ZS, Sud S, Craig MJ, Ying C, Pienta KJ. CCL2 and interleukin-6 promote survival of human CD11b+ peripheral blood mononuclear cells and induce M2-type macrophage polarization. J Biol Chem. 2009 Dec 4;284(49):34342–54.

63. Sierra-Filardi E, Nieto C, Domínguez-Soto A, Barroso R, Sánchez-Mateos P, Puig-Kroger A, et al. CCL2 shapes macrophage polarization by GM-CSF and M-CSF: identification of CCL2/CCR2-dependent gene expression profile. J Immunol. 2014 Apr 15;192(8):3858–67.

64. Tanaka T, Terada M, Ariyoshi K, Morimoto K. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1/CC chemokine ligand 2 enhances apoptotic cell removal by macrophages through Rac1 activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010 Sep 3;399(4):677–82.

65. Melo EM, Galvão I, Felix FB, Magalhães FM, Rago F, Machado MG, et al. Angiotensin-(1-7) treatment improves pneumonia and prevents sepsis caused by pneumococcal infection. [preprint]. 2025. Available from: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-6812678/v1.

66. Mendes S, Guimarães LC, Costa PAC, Fernandez CC, Figueiredo MM, Teixeira MM, et al. Intranasal liposomal angiotensin-(1-7) administration reduces inflammation and viral load in the lungs during SARS-CoV-2 infection in K18-hACE2 transgenic mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2024 Dec 5;68(12):e0083524.