Abstract

Introduction: This study aimed to explore the changes in ferroptosis markers and their relationship with fundus lesion severity in chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Methods: We enrolled 118 CKD patients and collected clinical, renal function, fundus imaging data, and ferroptosis markers. We performed correlation and regression analyses between renal dysfunction and fundus lesions, and assessed the changes and mediating roles of serum iron (Fe), malondialdehyde (MDA), and reduced glutathione (GSH) in CKD deterioration and retinal damage.

Results: Levels of Fe, MDA, and GSH showed significant differences across CKD stages (P<0.001). Logistic regression identified sex, mean arterial pressure, total cholesterol, hemoglobin, ferritin, Fe, MDA, and GSH as significant factors in CKD-related fundus lesions (P<0.05). MDA (β=0.15, 95%CI: 0.03–0.26) and GSH (β=0.33, 95%CI: 0.16–0.54) significantly mediated the link between renal decline and retinal damage (P ≤ 0.001).

Conclusions: Early fundus screening is clinically valuable for managing CKD progression. Fundus damage severity in CKD closely tracks renal decline, with ferroptosis likely playing a key role. MDA and GSH are promising biomarkers for early detection and intervention in CKD-related retinal pathology.

Keywords

Chronic kidney disease, Fundus disease, Ferroptosis

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD), marked by structural and/or functional renal impairment [1], affects 14.3% of the global population and represents a growing public health burden [2]. The eye and kidney exhibit anatomical and physiological parallels; microvascular changes in the retina and choroid may signal renal disease progression [3-4]. Fundus lesion severity appears to escalate with CKD progression, implying a mechanistic link between renal and retinal damage. Therefore, early detection and intervention are critical for improving CKD prognosis [5].

However, the mechanisms linking renal deterioration to fundus pathology remain elusive and demand further exploration. One important area of research is ferroptosis. Ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death, involves iron overload, oxidative stress, and lipid peroxidation, culminating in cellular and tissue damage [6]. It is implicated in diverse diseases, with clearer roles emerging in kidney and ocular damage. CKD progression exacerbates iron imbalance and oxidative stress, triggering ferroptosis and worsening tubular and interstitial injury [7]. Ferroptosis-driven oxidative stress may also compromise ocular microvasculature, fostering retinal pathology. Retinal and choroidal vessels are vulnerable to oxidative injury, which may enhance vascular leakage and trigger retinal lesions [8]. Biomarkers like Fe, MDA, and GSH are emerging indicators of CKD deterioration [9].

While initial work links ferroptosis to CKD, its mechanistic role in fundus pathology and stage-specific effects remain poorly defined. This study examines how fundus lesions relate to CKD progression and explores whether ferroptosis biomarkers mediate this relationship. We aim to identify stage-specific ferroptosis biomarkers to enhance early detection and guide precision therapy in CKD-related fundus disease. Furthermore, findings may also inform ferroptosis research beyond CKD.

Methods

Subjects

A total of 118 CKD patients with fundus lesions treated at Zigong First People’s Hospital (Feb 2023–Feb 2024) were enrolled per inclusion/exclusion criteria. All participants received both clinical care and ophthalmic evaluation. Inclusion: KDIGO-defined CKD, age ≥ 18, complete clinical/lab data, baseline and fundus exams, and informed consent. Exclusion criteria included: renal replacement therapy, ocular disease interfering with fundus imaging, major organ failure, diabetes, infections, RAS blockers, outside referrals, psychiatric illness.

Data collection

A cross-sectional study (n=118) with multiple imputations ensured data completeness and validity. Collected data included general information: sex, age, BMI, mean arterial pressure (MAP), hemoglobin, total cholesterol. Renal indices: creatinine, homocysteine, blood urea, 24-hour urine protein, urine albumin/urine creatinine ratio (ACR), β2-microglobulin. Fundus data: vessel density, avascular zones, choroid, and lesion grade. Ferroptosis biomarkers: ferritin, Fe, MDA and GSH. Data were obtained using standardized clinical and lab procedures. Ethical approval was obtained (Sichuan Geriatrics Center, No. 24LNYXSSB03).

Diagnosis and CKD staging

CKD stages were defined per KDIGO 2023 using eGFR (CKD-EPI formula). CKD staging criteria are as follows: CKD1 stage: GFR essentially normal >90 ml (min-1.73m2); CKD2 stage: GFR mildly reduced 60-89 ml/(min-1.73m2); CKD3 stage: GFR mildly to moderately reduced 30-59 ml/(min-1.73m2); CKD4 stage: GFR severely reduced 15-29 ml/(min-1.73m2); CKD5: ESRD with GFR <15 ml/(min-1.73m2).

Grading of fundus

Fundus lesions were graded I–IV based on severity: Grade I: mild retinal arteriolar narrowing; Grade II: obvious narrowing with increased arteriole reflex, showing copper/silver wire appearance; Grade III: presence of cotton-wool spots, hard exudates, widespread hemorrhage; Grade IV: above plus optic disc edema and arteriosclerosis-related complications.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 25.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics) software. Normally distributed data are presented as mean ± SD; skewed data as median (IQR). Categorical data were reported as counts and percentages. For group comparisons: one-way ANOVA was used for normally distributed data with equal variances; Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normal or heteroscedastic data; Chi-square test for categorical variables; Kendall’s tau-b for ordinal variables. Ordinal logistic regression was applied for multivariable analysis. Mediation was tested using SPSS Process Macro (Model 4) with Hayes’ bootstrap method. Two-sided tests were used; significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Statistical description of general information and analysis of differences

This study included 118 CKD-confirmed patients, with a mean age of 61.71 ± 13.90 years and a median BMI of 18.00 (16.30, 19.10) kg/m². The cohort consisted of 58 males (49.2%) and 60 females (50.8%). Patients were stratified into CKD stages 1–5 by eGFR: 2 (1.6%), 14 (11.9%), 32 (27.1%), 22 (18.7%), and 48 (40.7%), respectively. Significant differences in age, MAP, hemoglobin, total cholesterol, homocysteine, and GSH levels were found across CKD stages (all P<0.05). Significant differences in MAP, BUN, 24 h proteinuria, ACR, β2-microglobulin, Fe, and MDA were observed across CKD stages (P<0.05). Other general and renal-related parameters showed no significant variation (P>0.05). The details of basic information, systemic parameters, and renal function-related indexes of the study subjects are provided in Table 1.

|

|

CKD2 (n=14) |

CKD3 (n=32) |

CKD4 (n=22) |

CKD5 (n=48) |

Total population (n=118) |

P |

|

Basic Information |

||||||

|

Sex ratio (m/f) |

(4/3) |

(10/6) |

(6/5) |

(9/15) |

(29/30) |

0.445# |

|

Age (years) |

50.57 ± 22.50 |

64.06 ± 9.41 |

68.91 ± 15.51 |

61.13 ± 9.99 |

61.71 ± 13.90 |

0.020* |

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

16.90 (16.30, 18.15) |

17.05 (15.90, 18.12) |

17.80 (16.20, 19.35) |

18.70 (17.33, 19.70) |

18.00 (16.30, 19.10) |

0. 196 |

|

Mean arterial pressure (MAP) (mmhg) |

116.5 (106, 119) |

118 (113, 139) |

107 (96, 119) |

129 (116, 135) |

119 (114, 133) |

<0.001 |

|

Hemoglobin (g/L) |

140.57 ± 14.66 |

128.00 ± 22.71 |

105.64 ± 13.87 |

89.75 ± 16.72 |

110.00 ± 26.32 |

<0.001* |

|

Total cholesterol (mmol/L) |

6.17 ± 1.33 |

5.23 ± 1.60 |

5.04±1.62 |

4.23 ± 1.28 |

4.90 ± 1.54 |

0.034* |

|

Renal function related indicators |

||||||

|

Homocysteine (μmol/L) |

16.18±3.15 |

20.78±6.47 |

23.04±10.00 |

26.54±8.67 |

22.74±8.65 |

0.013* |

|

Blood urea (mmol/L) |

5.97 (4.92, 7.23) |

10.57 (8.86, 11.07) |

14.75 (9.72, 17.98) |

24.29 (17.55, 31.36) |

12.08 (9.20, 19.65) |

<0.001 |

|

24-hour urine protein (mg/24h) |

139.00 (94.25, 177.75) |

189.50 (131.75, 630.00) |

301.50 (116.75, 1389.50) |

1096.00 (704.00, 2190.00) |

613.00 (162.00, 1358.50) |

0.002 |

|

ACR (mg/mmol) |

4.60 (1.16, 6.08) |

5.83 (2.07, 37.32) |

29.68 (3.98, 71.90) |

86.21 (47.37, 207.38) |

32.89 (4.93, 96.42) |

<0.001 |

|

Blood β2-microglobulin (mg/L) |

2.17 (1.88, 2.80) |

3.60 (3.02, 4.03) |

7.36 (5.43, 9.71) |

16.04 (12.15, 21.80) |

8.62 (3.65, 16.04) |

<0.001 |

|

Ferroptosis markers |

||||||

|

Ferritin (ng/ml) |

265.45 (222.78, 1054.98) |

254.3 (140.70, 548.70) |

156.9(115.10, 292.90) |

395.00 (212.63, 776.27) |

291.55 (145.50, 548.90) |

0.190 |

|

Fe (umol/L) |

46.65 (30.43, 55.57) |

38.77 (35.34, 41.96) |

32.18 (30.29, 36.9) |

28.93 (21.61, 30.66) |

31.33 (26.90, 38.77) |

<0.001 |

|

MDA (nmol/ml) |

7.18 (5.93, 7.77) |

8.24 (7.35, 9.12) |

9.15 (8.59, 9.71) |

12.63 (9.83, 14.61) |

9.30 (7.94, 12.91) |

<0.001 |

|

GSH (umol/L) |

500.00 ± 54.15 |

413.75 ± 55.66 |

351.95 ± 60.50 |

252.10 ± 70.13 |

348.23 ± 109.16 |

<0.001* |

|

Note: Urine microalbumin/urine creatinine (ACR), serum iron (Fe), malondialdehyde (MDA), and reduced glutathione (GSH). * denotes one-way ANOVA for comparisons between groups; # denotes chi-square test for comparisons between groups; the Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum test for the rest of the comparisons between groups; P<0.05 is considered statistically significant. |

||||||

The study enrolled 72 subjects who underwent OCTA examinations, comprising a total of 142 eyes. Study findings revealed that retinal vascular density varied significantly among different stages of kidney function (p=0.001). However, no statistically significant differences were found in other fundus parameters (p>0.05), as detailed in Table 2, Figures 1 and 2.

|

|

CKD1 (n=2) |

CKD2 (n=12) |

CKD3 (n=30) |

CKD4 (n=28) |

CKD5 (n=68) |

Total population (n=142) |

P |

|

Vision |

0.8 (0.8, 0.8) |

0.9 (0.4, 1.0) |

0.6 (0.5, 0.8) |

0.7 (0.4, 0.8) |

0.6 (0.4, 0.8) |

0.6 (0.4, 0.8) |

0.352 |

|

Retinal thickness (mm) |

279.0 (278.5, 279.5) |

302.0 (297.0, 304.8) |

303.0 (289.5, 319.5) |

290.5 (277.5, 295.5) |

285.0 (280.3, 300.5) |

291.0 (281.0, 305.0) |

0.090 |

|

Vessel density (%) |

17.5 (16.88, 18.3) |

27.0 (26.3, 30.8) |

28.0 (24.0, 31.0) |

33.5 (25.5, 39.5) |

39.0 (32.3, 41.0) |

33.0 (27.0, 40.0) |

0.001 |

|

FAZ area (mm2) |

0.2 (0.2, 0.3) |

0.2 (0.2, 0.3) |

0.3 (0.2, 0.5) |

0.4 (0.2, 0.5) |

0.3 (0.2, 0.5) |

0.3 (0.2, 0.5) |

0.662 |

|

FAZ circumference (mm) |

2.3 (2.2, 2.4) |

2.2 (1.8, 2.9) |

2.6 (2.3, 3.3) |

2.4 (2.0, 3.0) |

2.3 (1.9, 3.0) |

2.4 (2.0, 3.0) |

0.557 |

|

Choroidal thickness (μm) |

182.5 (182.3, 182.8) |

194.3 (186.8, 241.9) |

169.0 (122.5, 266.5) |

172.5 (86.5, 255.5) |

180.5 (107.6, 242.6) |

185.0 (120.5, 252.3) |

0.799 |

|

Choroidal vascular index |

30.0 (28.5, 31.5) |

36.5 (36.0, 37.8) |

30.0 (25.5, 32.5) |

32.5 (29.0, 34.8) |

29.0 (24.3, 35.0) |

31.0 (26.0, 35.0) |

0.107 |

|

Note: Visual acuity was calculated as the average visual acuity of both eyes. Retinal and choroidal parameters, including retinal thickness, vascular density, choroidal thickness, and choroidal vascular index, were measured at 600 μm from the central macular recess in the directions of both the nasal and temporal retinas. The acricularity index was defined as the ratio of circumference to the area of the avascular area of the retina. Differences between groups were evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test, with P<0.05 considered statistically significant. |

|||||||

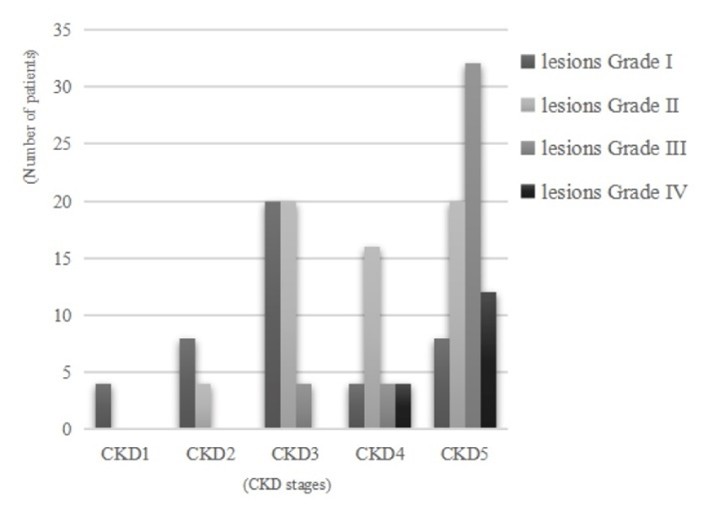

Figure 1. Fundus grading in patients with different stages of CKD.

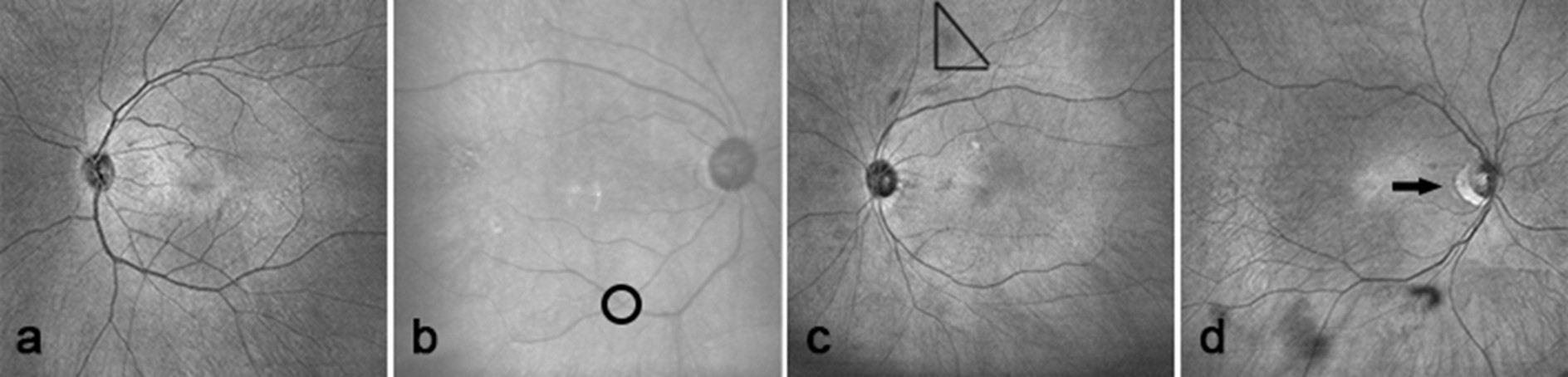

Figure 2. OCTA fundus images of patients with different fundus classifications. The mild spasm and thinning of the retinal artery have been shown in Figure 2a, which was graded as I. The cross-pressure traces of the arterioles marked by circles have been shown in Figure 2b, which was graded as II. The coppery change in the retinal arteries, with scattered punctate hemorrhagic exudates visible in the retina marked by triangles have been shown in Figure 2c, which was graded as III. The changes in Figure 2c and optic disc edema marked by arrows have been shown in Figure 2d, which was graded as IV.

Correlation analysisCKD stage was significantly correlated with fundus lesion severity (Kendall's tau-b = 0.494, P < 0.001). The detailed composition ratio is shown in Table 3.

|

Funduscopic grading |

Renal function staging |

Kendall's tau-b |

P |

|||||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

Total |

0.494 |

<0.001 |

|

|

1 |

(4, 2.5%) |

(8, 5%) |

(20, 12.5%) |

(4, 2.5%) |

(8, 5%) |

(44, 27.5%) |

||

|

2 |

(0, 0%) |

(4, 2.5%) |

(20, 12.5%) |

(16, 10%) |

(20, 12.5%) |

(60, 37.5%) |

||

|

3 |

(0, 0%) |

(0, 0%) |

(4, 2.5%) |

(4, 2.5%) |

(32, 20%) |

(40, 25%) |

||

|

4 |

(0, 0%) |

(0, 0%) |

(0, 0%) |

(4, 2.5%) |

(12, 7.5%) |

(16, 10%) |

||

|

Total |

(4, 2.5%) |

(12, 7.5%) |

(44, 27.5%) |

(28, 17.5%) |

(72, 45%) |

(160, 100%) |

||

|

Note: Categorical data are expressed as (n,%); comparisons between groups were performed using Kendall's tau-b correlation analysis. |

||||||||

Ordered logistic regression analysis

An ordinal logistic regression was performed to assess the impact of ferroptosis markers, fundus damage grade, and covariates (sex, age, MAP, cholesterol, Hb, ferritin, Fe, MDA, GSH). Results showed that age showed no significant effect on CKD progression (β = 0.013, P = 0.783), male sex was linked to greater CKD progression risk (β = -3.855, P = 0.025), elevated MAP was associated with worsened renal function (β = 0.189, P = 0.032). Higher levels of cholesterol, Hb, ferritin, Fe, and GSH were protective against renal deterioration (all P<0.05). Elevated MDA was a risk factor for CKD progression (β = 1.354, P = 0.015). Fundus damage risk rose with CKD severity, notably higher in stages III–IV than I–II (P<0.05). Details of the specific influencing factors can be found in Table 4.

|

Influencing factors |

β |

Standard Error (SE) |

β 95%CI |

P |

|

Intercept 1 ([CKD 1]) |

-78.980 |

31.591 |

-140.90~-17.06 |

0.012 |

|

Intercept 2 ([CKD 2]) |

-77.147 |

31.490 |

-138.87~-15.43 |

0.014 |

|

Intercept 3 ([CKD 3]) |

-63.461 |

27.176 |

-116.73~-10.20 |

0.020 |

|

Intercept 4 ([CKD 4]) |

-47.010 |

20.745 |

-87.67~-6.35 |

0.023 |

|

Male (Female = reference group) |

-3.855 |

1.723 |

-7.23~-0.48 |

0.025 |

|

Age |

0.013 |

0.049 |

-0.08~0.11 |

0.783 |

|

Mean arterial pressure |

0.189 |

0.088 |

0.02~0.36 |

0.032 |

|

Total cholesterol |

-2.429 |

0.994 |

-4.38~-0.48 |

0.015 |

|

Hemoglobin |

-0.422 |

0.182 |

-0.78~-0.07 |

0.020 |

|

Ferritin |

-0.014 |

0.007 |

-0.03~0.00 |

0.036 |

|

Fe |

-0.470 |

0.195 |

-0.85~-0.09 |

0.016 |

|

MDA |

1.354 |

0.557 |

0.26~2.44 |

0.015 |

|

GSH |

-0.062 |

0.024 |

-0.11~-0.01 |

0.010 |

|

Fundus lesions grade 1 (grade 4 = reference group) |

12.937 |

5.529 |

2.10~23.77 |

0.019 |

|

Fundus lesions grade 2 (grade 4 = reference group) |

11.531 |

4.255 |

3.19~19.87 |

0.007 |

|

Fundus lesions grade 3 (grade 4 = reference group) |

17.608 |

7.134 |

3.63~31.59 |

0.014 |

Mediating effect analysis

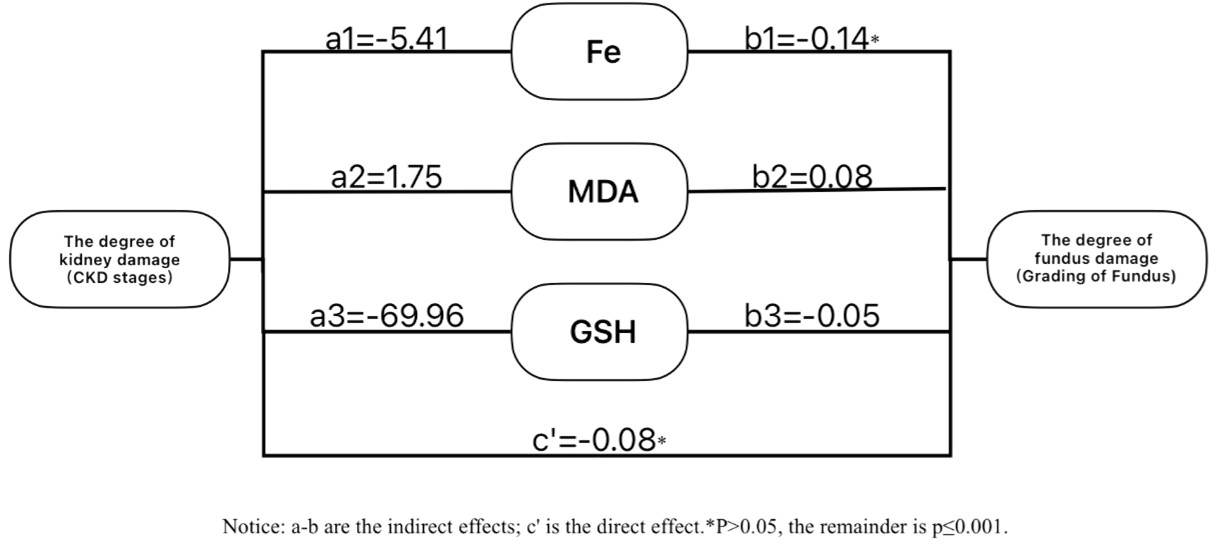

Ferroptosis markers were introduced as mediators in a structural equation model to examine their role between CKD stage and fundus damage. Specific path coefficients are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Path coefficient plots of the extent of renal damage, ferroptosis biomarkers (Fe, MDA, GSH) and the extent of fundus damage in CKD patients.

Bootstrap analysis (Table 5) showed that ferroptosis markers (Fe, MDA, GSH) mediated the effect of CKD stage on fundus damage. The total effect was 0.63, with an indirect effect of 0.55 (87%) and a non-significant direct effect of 0.08 (13%, β = 0.08, 95% CI: -0.34 to 0.17). Fe showed weak, non-significant mediation (β = 0.08), while MDA (β = 0.15, CI: 0.03–0.26) and GSH (β = 0.33, CI: 0.16–0.54) had significant effects, with GSH playing a dominant mediating role.

|

Effect Type |

β |

Standard Error (SE) |

β 95%CI |

Effect Proportion |

|

Total effect |

0.63 |

0.08 |

(0.31, 0.63) |

|

|

Direct effect |

0.08 |

0.13 |

(-0.34, 0.17) |

13% |

|

Indirect effect (mediating effect) |

0.55 |

0.13 |

(0.28, 0.81) |

87% |

|

Mediating effect of Fe |

0.08 |

0.06 |

(-0.06, 0.22) |

|

|

Mediating effect of MDA |

0.15 |

0.06 |

(0.03, 0.26) |

|

|

Mediating effect of GSH |

0.33 |

0.10 |

(0.16, 0.54) |

Discussion

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of programmed cell death, and recent research has highlighted its significant role in multiple diseases, especially in the progression of ischemia-reperfusion injury, kidney disease, and retinal degeneration. Ferroptosis can cause damage to kidney tissue and the retinal microenvironment through mechanisms like iron accumulation, oxidative stress, and lipid peroxidation, accelerating kidney function deterioration and facilitating the development and progression of retinal disease.

In this study, the relationship between ferroptosis biomarkers (Fe, MDA, GSH), CKD staging, and retinal lesions was analyzed, revealing that oxidative stress and ferroptosis play crucial roles in renal deterioration and retinal damage. MDA and GSH, as critical markers of ferroptosis, may mediate the development of retinal lesions during CKD progression through indirect effects. However, the effect of Fe is weak, likely due to the complexity and multifaceted nature of ferroptosis regulation. This discovery implies that future research should further investigate the specific mechanisms of ferroptosis and assess the multidimensional roles of various biomarkers in CKD-associated retinal degeneration.

Studies show that iron accumulation in renal tubular cells is a crucial factor in causing kidney damage, and by intensifying oxidative stress, it further damages the tubular structure, resulting in the ongoing deterioration of renal function [10]. Furthermore, elevated GSH levels can mitigate ferroptosis-mediated renal damage and fibrosis [11]. MDA, an important marker of lipid peroxidation, is positively correlated with a decrease in glomerular filtration rate, suggesting that as CKD progresses, oxidative stress worsens, and ferroptosis could be a central driver of kidney damage [12]. Furthermore, animal experiments reinforce this concept. In a unilateral ureteral ligation model, the ferroptosis inhibitor Kaempferol significantly reduced iron accumulation and MDA levels in renal tubular cells while increasing GSH levels through the inhibition of NOX4-mediated ferroptosis. This mechanism displayed a potential protective role in reducing tubular necrosis, suppressing inflammation, and preventing fibrosis [13]. The findings of this study indicate that as CKD stages advance, serum Fe and MDA levels rise, while GSH levels significantly decrease, confirming the crucial role of ferroptosis in CKD progression.

The retina is a metabolically active neural tissue, and its microvessels and neurons are particularly sensitive to oxidative stress. Recent studies indicate that ferroptosis plays a crucial role in retinal damage and retinal degeneration, particularly under excessive oxidative stress, where ferroptosis can enhance free radical generation, induce lipid peroxidation of cell membranes, and worsen retinal lesions [14]. Research has shown that abnormal levels of MDA and GSH may contribute significantly to retinal photoreceptor damage. In the retinal ischemia/reperfusion injury mouse model, retinal ganglion cells, photoreceptor cells, and pigment epithelial cells exhibited mitochondrial shrinkage, along with iron accumulation, increased reactive oxygen species, elevated MDA levels, and reduced GSH levels, leading to significant visual function damage. The ferroptosis inhibitor deferoxamine can partially protect retinal structure and function by inhibiting transferrin expression, reducing ferritin degradation, and activating the Xc-GSH-GPX4 pathway [15]. In the study of light-induced retinal degeneration, photoreceptor cells showed iron accumulation, mitochondrial shrinkage, GSH depletion, and increased MDA levels after exposure to light, along with reduced expression of key ferroptosis molecules SLC7A11 and GPX4. The ferroptosis inhibitor Ferrostatin-1 significantly reduced light-induced ferroptosis, suggesting that ferroptosis may serve as a crucial therapeutic target for retinal degeneration [16]. The decline in GSH levels can further promote ferroptosis, autophagy, and cellular senescence, reducing retinal cell tolerance to oxidative damage and aggravating cell apoptosis and retinal deterioration [17]. Based on the results of this study, it is suggested that ferroptosis may manifest through increased vascular permeability and oxidative stress, characterized by elevated MDA levels and decreased GSH levels, thus influencing the health of retinal blood vessels. This highlights the potential predictive value of ferroptosis biomarkers in retinal damage.

The precise mechanisms of ferroptosis in renal damage and retinal lesions in CKD patients remain unclear. However, based on the results of the ordered logistic regression analysis in this study, the role of ferroptosis biomarkers (MDA, GSH) in retinal damage becomes more pronounced as kidney function worsens, particularly in advanced CKD patients. Further mediation analysis reveals that the indirect mediation effects of MDA and GSH are significant, suggesting that ferroptosis in CKD patients may influence retinal vascular function via oxidative stress mechanisms, acting as a bridge between CKD and retinal degeneration. However, the mediation effect of serum iron is weak and not statistically significant, which may be due to the complexity and diversity of ferroptosis regulation. This discovery implies that future research should further investigate the specific mechanisms of ferroptosis and examine the multifaceted roles of various biomarkers in CKD-related retinal degeneration.

Moreover, this study revealed that mild to moderate retinal lesions are prevalent in CKD patients, underscoring the need for early retinal screening. However, the proportion of CKD stage 1 patients in this study was the lowest, likely due to the lack of obvious symptoms in early-stage kidney disease, as well as limited public awareness of CKD and its retinal complications [18]. Some patients perceive retinal examinations as time-consuming and financially burdensome, while others have anxiety about blood draws and injections [19], which reduce compliance with CKD screening and regular follow-up.

Recent studies have highlighted the role of Sirtuins, a family of anti-apoptotic and anti-aging proteins [20], in protecting multiple organs—including the kidney, liver, heart, and brain—from pathological damage [21], and may be early ferroptosis biomarker or retinal lesions and the progression of kidney function in CKD patients. Notably, Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) can reduce ferroptosis and reduce CKD progression [22]. Furthermore, studies have confirmed the importance of Sirtuin 1 activators and inhibitors in preventing ferroptosis with relevance to the initiation and progression of retinopathy [23]. These findings support the therapeutic potential of targeting SIRT1 in the management of CKD-associated retinal degeneration.

In summary, future treatment strategies could involve regulating ferroptosis-related biomarkers (MDA, GSH) to improve retinal health in CKD patients, thereby slowing the onset and progression of retinal degeneration. Nusinovici et al. [24] recommend that CKD patients receive regular ophthalmic exams and emphasize the need for enhanced interdisciplinary collaboration between nephrology and ophthalmology to optimize overall patient care.

Limitations and Conclusion

This study examined the relationship between retinal lesions and the progression of kidney function in CKD patients and assessed the role of ferroptosis biomarkers in retinal damage. The results indicated that retinal lesions were significantly linked to kidney function impairment in CKD patients, and the elevated MDA levels and reduced GSH levels of ferroptosis biomarkers suggest that ferroptosis might play a key role in the initiation and progression of retinal lesions, with MDA and GSH potentially serving as early biomarkers. These findings are in line with previous studies, further confirming the association between CKD and retinal lesions, while uncovering the potential mechanisms of ferroptosis in retinal degeneration, offering new insights to the existing literature and expanding the pathological research on retinal lesions.

However, there are some limitations to this study, including a small sample size, a cross-sectional design that limits causal analysis, and data missingness, which may affect the generalizability of the results.

Future research should include long-term follow-up studies to further define the causal link between abnormalities in ferroptosis biomarkers and CKD-related retinal damage. Additionally, the ferroptosis mechanism should be investigated as a potential therapeutic target, to assess whether modulating ferroptosis can slow down or improve CKD-related retinal damage. In addition, more clinical trials are required to validate the clinical utility of ferroptosis biomarkers such as MDA and GSH in early diagnosis and treatment decisions for CKD-related retinal lesions, improving the clinical translational potential of these findings.

References

2. Ene-Iordache B, Perico N, Bikbov B, Carminati S, Remuzzi A, Perna A, et al. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk in six regions of the world (ISN-KDDC): a cross-sectional study. Lancet Glob Health. 2016 May;4(5):e307-19.

3. Wong CW, Wong TY, Cheng CY, Sabanayagam C. Kidney and eye diseases: common risk factors, etiological mechanisms, and pathways. Kidney Int. 2014 Jun;85(6):1290-302.

4. Farrah TE, Dhillon B, Keane PA, Webb DJ, Dhaun N. The eye, the kidney, and cardiovascular disease: old concepts, better tools, and new horizons. Kidney Int. 2020 Aug;98(2):323-42.

5. Wong CW, Lamoureux EL, Cheng CY, Cheung GC, Tai ES, Wong TY, et al. Increased Burden of Vision Impairment and Eye Diseases in Persons with Chronic Kidney Disease - A Population-Based Study. EBioMedicine. 2016 Jan 19;5:193-7.

6. Yan HF, Zou T, Tuo QZ, Xu S, Li H, Belaidi AA, et al. Ferroptosis: mechanisms and links with diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021 Feb 3;6(1):49.

7. Guo R, Duan J, Pan S, Cheng F, Qiao Y, Feng Q, et al. The Road from AKI to CKD: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets of Ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2023 Jul 13;14(7):426.

8. Liu K, Li H, Wang F, Su Y. Ferroptosis: mechanisms and advances in ocular diseases. Mol Cell Biochem. 2023 Sep;478(9):2081-95.

9. Zeng F, Nijiati S, Tang L, Ye J, Zhou Z, Chen X. Ferroptosis Detection: From Approaches to Applications. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2023 Aug 28;62(35):e202300379.

10. Packer M. Iron homeostasis, recycling and vulnerability in the stressed kidney: A neglected dimension of iron-deficient heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2024 Jul;26(7):1631-41.

11. Dong XQ, Chu LK, Cao X, Xiong QW, Mao YM, Chen CH, et al. Glutathione metabolism rewiring protects renal tubule cells against cisplatin-induced apoptosis and ferroptosis. Redox Rep. 2023 Dec;28(1):2152607.

12. Tomás-Simó P, D'Marco L, Romero-Parra M, Tormos-Muñoz MC, Sáez G, Torregrosa I, et al. Oxidative Stress in Non-Dialysis-Dependent Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jul 23;18(15):7806.

13. Li J, Yang J, Xian Q, Su H, Ni Y, Wang L. Kaempferitrin attenuates unilateral ureteral obstruction-induced renal inflammation and fibrosis in mice by inhibiting NOX4-mediated tubular ferroptosis. Phytother Res. 2024 Jun;38(6):2656-68.

14. Hao XD, Xu WH, Zhang X, Xue J. Targeting ferroptosis: a novel therapeutic strategy for the treatment of retinal diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2024 Oct 30;15:1489877.

15. Wang X, Li M, Diao K, Wang Y, Chen H, Zhao Z, et al. Deferoxamine attenuates visual impairment in retinal ischemia‒reperfusion via inhibiting ferroptosis. Sci Rep. 2023 Nov 17;13(1):20145.

16. Tang W, Guo J, Liu W, Ma J, Xu G. Ferrostatin-1 attenuates ferroptosis and protects the retina against light-induced retinal degeneration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021 Apr 9;548:27-34.

17. Sun Y, Zheng Y, Wang C, Liu Y. Glutathione depletion induces ferroptosis, autophagy, and premature cell senescence in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Cell Death Dis. 2018 Jul 9;9(7):753.

18. National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002 Feb;39(2 Suppl 1):S1-266.

19. Deacon B, Abramowitz J. Fear of needles and vasovagal reactions among phlebotomy patients. J Anxiety Disord. 2006;20(7):946-60.

20. Martins IJ. Anti-aging genes improve appetite regulation and reverse cell senescence and apoptosis in global populations. Advances in Aging Research. 2016;5(1):9-26.

21. Martins IJ. Single gene inactivation with implications to diabetes and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Journal of Clinical Epigenetics. 2017 Aug 1;3(3):1-8.

22. Jin Q, Ma F, Liu T, Yang L, Mao H, Wang Y, et al. Sirtuins in kidney diseases: potential mechanism and therapeutic targets. Cell Commun Signal. 2024 Feb 12;22(1):114.

23. Martins I. Sirtuin 1, a diagnostic protein marker and its relevance to chronic disease and therapeutic drug interventions. EC Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2018;6(4): 209-15.

24. Nusinovici S, Sabanayagam C, Teo BW, Tan GSW, Wong TY. Vision Impairment in CKD Patients: Epidemiology, Mechanisms, Differential Diagnoses, and Prevention. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019 Jun;73(6):846-57.