Commentary

Camping trips are often a lot of work, especially with children. Purchasing supplies, ?nding a location, and dealing with scary animals are often just too much. Inspired by so many ?lms, my family instead set up a tent to camp in the backyard. This approach o?ered the allure of a majestic camping trip with an enchanting tent, delicious smores, and scary stories as well as the convenience of a secure home with snacks, a warm bed, and showers if the night grew blustery. In many ways, moieties that target the extracellular matrix (ECM) of tissues camp in the backyards of cells. These binding moieties take advantage of the unique opportunities of backyard camping like not being restricted by “house rules” but still maintain a close enough proximity to a cell (equivalent to a house in this analogy) to ?ee from an unexpected rainstorm. We propose the bene?ts of backyard camping for ECM binding moieties include: slower degradation of targeting ligands due to less recycling/salvage pathways extracellularly (campers do not have to vacuum), ECM binding moieties have greater space to bind a speci?c tissue (campers can explore the great outdoors), and ECM binding moieties can occupy more sites in the tissue (camping is always more fun with friends!) [1-3]. In the manuscript entitled “Identi?cation of Brain ECM Binding Variable Lymphocyte Receptors Using Yeast Surface Display” we present methods for identifying Variable Lymphocyte Receptors (VLRs) that bind and accumulate in brain ECM, aka camp in the backyard of brain cells [4].

VLRs perform similar functions to antibodies in the jawless ?sh, lamprey, and have unique features that make these molecules ideal for camping in the backyard of brain cells [5]. Jawless vertebrates are approximately 500 million years removed from mammals, which allows for the raising of VLRs against ECM proteins (via vaccination) which are removed from the B cell repertoire due to homology with native ECM [6]. Additionally, VLRs have a high proclivity for binding glycosylated proteins [7]. The entirety of the apical cell membrane, and many proteins secreted into ECM, are sugarcoated making glyco-binding a highly desirable feature. Finally, methods for generating yeast surface display VLR libraries from vaccinated lamprey are available [8,9]. The manuscript described above uses a VLR library generated by vaccinating larval lamprey with mechanically harvested murine microvessels to ensure the glycocalyx remains intact. VLRs from vaccinated lamprey are ampli?ed by PCR, similar to B cell PCR sewing strategies used to generate scFv libraries, then cloned into a vector that displays VLRs attached to the surface of yeast via a pair of disul?de bonds.

The disul?de connection between the VLR and yeast surface plays a major role in the method used to identify VLRs that camp (or accumulate) on the lawn of brain cells. A typical yeast surface display selection protocol is coupled with an ELISA-based screening assay, in series, to identify VLRs that preferentially accumulate in Brain ECM compared to ECM found in all tissues. Combining selection and screening assays facilitates the identi?cation of clones with high tissue speci?city. In the study above, brain cells are seeded in tissue culture vessels at low densities and allowed to grow over several days to allow for secretion and modi?cation of ECM. Then, ?asks undergo a gentle cell lysis/detachment procedure consisting of either washing in light detergent followed by nuclease treatment, or treatment with EDTA, to expose the ECM. In contrast to our initial opinion that EDTA treatment is less harsh and would leave more ECM intact than detergent washes, recent studies performed in our laboratory indicate treatment with EDTA removes calcium and other essential cofactors from the ECM (as well as prevents integrin binding) that results in reduced in vitro binding of VLRs to exposed brain ECM compared to treatment with detergent. Exposed ECM is then used as bait to enrich VLRs that accumulate in brain ECM via typical yeast surface selection protocols. Next, secondary screens are used on the enriched population of VLRs that bind ECM to identify VLR clones that preferentially bind brain ECM compared to ECM components common to all tissues. In the study described above, VLR clones are expanded in individual wells, then the disul?de bonds between the yeast surface and the VLR are reduced to liberate VLRs from the yeast surface. VLRs from a single well are split into two groups; the ?rst group is incubated with brain-derived ECM and the second group is incubated with ?broblast-derived ECM. Finally, an ELISA-based detection method quanti?es the amount of VLR bound to each type of ECM. Clones with a high preference for brain ECM (compared to control ECM) are identi?ed by sequencing plasmids from the original well of yeast that had VLRs removed from the surface for screening. Variations on these techniques are used to identify lead VLR candidates that can preferentially camp in the backyard of brain cells.

Benefits of Camping in the Backyard Versus Staying in the House

Using VLRs that accumulate in the extracellular matrix (aka camp in the backyard) demonstrates numerous potential bene?ts compared to those accumulating with cells (aka staying in the house). While a house o?ers more protection from the elements, houses are also cleaned more often. A tent, and the camper, must clean up at the end of the trip, but while basking in the great outdoors, hygiene is often not the ?rst concern. Similarly, VLRs that accumulate intercellularly are subject to degradation via proteases, recycling via autophagy, and garbage removal via vesicle tra?cking [10-14]. Stable, membrane-bound targeting ligands are removed from the cell surface continually via the CLIC/GEEC pathway of non-speci?c membrane turnover [15]. These features are essential for cellular health but also hamper tissue accumulation of VLRs. Accumulation in ECM does carry other risks, such as protein cleavage by secreted peptidases and mechanical degradation from ?uid ?ow, but ECM is generally stable, lacks metabolic function, and is uniformly expressed throughout a tissue. Thus, purely from an accumulation standpoint, ECM binding presents many desirable features compared to cellular accumulation.

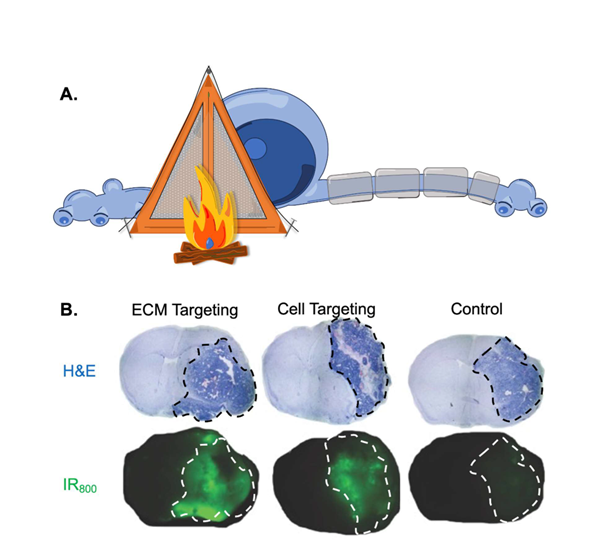

Additionally, the uniformity and stability of ECM may facilitate increased penetration of targeting ligands into a tissue. Cells continually replace membranes, and consequently, the proteins associated with that membrane, via lipid recycling and vesicle budding. Thus, it is impossible, in most cases, to saturate all of the binding receptors on the cell surface [16]. In contrast, ECM-binding VLRs can saturate ECM ligands near blood vessels forcing VLRs to bind ligands further into the tissue. This feature potentially enhances the uniform distribution of targeting ligands in a tissue to improve the delivery of therapeutic throughout the entire tissue rather than simply near the blood vessels. Di?erential staining between a targeting ligand that binds a cellular (punctate) and ECM (di?use) receptor are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A) Graphic symbolizing the idea that brain extracellular matrix (ECM) binding ligands camp in the backyard of a neuron instead of within the cell body. B) A mouse bearing an orthotopic brain tumor is treated with affinity matched ECM binding moiety, cell binding moiety, or negative control. The top panel is whole brain sections stained with H&E to define the tumor region (inside dashed line). The lower panel is whole brain sections depicting the signal from IR800 labelled binding moiety from a sequential brain slice. The tumor region in the lower panel is indicated by a white dashed line. We observe uniform distribution throughout the tumor with the ECM binding moiety compared to punctate distribution with the cell binding moiety.

Finally, the brain is a unique case in which the ECM is not normally exposed to blood components. In a healthy brain, complex systems termed the Blood-Brain barrier (BBB) separate brain ECM from the bloodstream [17]. Thus, targeting brain ECM speci?cally facilitates the accumulation of VLR in diseased regions of the brain. This approach provides regiospeci?city and prevents the need to target “diseased ECM”, to potentially expand the utility of brain ECM binding VLRs. In a recent manuscript, we demonstrate the ability to accumulate dyes and particles speci?cally in regions of the brain with tumors due to the breakdown of BBB within a brain tumor [9]. Targeting normal brain ECM limits the need to stratify patients by expression of mutant antigens because VLRs bind normal brain ECM components that are uniformly expressed in all humans as part of normal physiology. Targeting the underlying physiology of encephalopathies also expands the potential utility of this molecule beyond brain tumors. Diseases including acute conditions such as traumatic brain injury and stroke result in transient exposure of brain ECM [18]. Additionally, chronic conditions such as brain tumors, Multiple Sclerosis, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s disease also expose brain ECM to blood components [19-21]. Thus, brain ECM-binding VLRs could have signi?cant utility in treating multiple encephalopathies potentially justifying the expense associated with developing novel targeting ligands to treat neurological diseases.

Camping in the Backyard of Human Brains

While we highlight the unique approach and bene?ts of identifying VLRs that bind brain ECM for treating neurological disease, many obstacles hinder the utility of brain ECM-binding VLRs to treat human disease. One of the bene?ts of backyard camping is that children are protected against strangers that roam public campgrounds. VLRs are derived from lamprey and thus strangers in the human body. Immunological responses such as agglutination and opsonization by antibodies will prevent repeated dosing and drastically diminish the potency of VLR targeting and accumulation over time. Fortunately, the structure of VLRs does have some human mimetics [22,23]. VLRs consist of a series of leucine repeats organized into a crescent shape with a stock or tail at the c-terminus. Human homologs including DARPins and Slit proteins have a similar structure [24]. Libraries made from these proteins could utilize the selection and screening methods described above to identify human homologs that speci?cally accumulate in brain ECM. Unfortunately, this approach does not bene?t from the recombination that occurs after vaccinating a lamprey. Grafting VLR loops onto human protein sca?olds may also reduce immunogenicity and retain brain ECM binding activity while still bene?ting from lamprey vaccination.

Retaining brain ECM binding activity after modifying VLRs with a therapeutic entity is another major challenge to translating this approach to human disease. We propose using brain ECM VLRs as a targeting ligand that is attached to therapeutic cargo. Small molecules, enzymes, or particles can all serve as therapeutic cargo, but must ?rst be attached to the VLR. Given the complex crescent shape required to bind glycosylated proteins, a non-speci?c modi?cation strategy such as non-covalent attachment to lysine or cysteine residues often results in reduced brain ECM-binding activity. We propose using Express Protein Ligation (EPL) to speci?cally modify the c-terminus of a VLR using inteins [25,26]. Methods describing protocols for modifying VLRs produced in yeast with dyes and particles are available. We recently extended these studies to modify VLRs produced in human 293F cells using the 20208 intein-based system. Production in human cells facilitates site-speci?c modi?cation of VLRs using a common, scalable biotechnology culture system for producing VLRs at a patient scale.

Finally, we propose using brain ECM as a targeting ligand rather than a stand-alone therapy. As discussed above, brain ECM-targeting ligands are generally coupled with a therapeutic modality to treat encephalopathies. This approach increases the barrier to human translation because multiple new modalities require safety and e?cacy testing before approval to treat human diseases. Further, producing brain ECM-binding treatment platforms at the patient scale is at least twice as expensive because two modalities are generated that must function together to achieve the desired patient bene?t. Once approved, brain ECM-targeting ligands could be useful for treating multiple types of neurological disorders, but substantial time, resources, and monetary investments are needed to achieve this goal.

In conclusion, targeting brain ECM via VLRs is an innovative solution to multiple problems that plague the delivery of brain therapeutics including preferential delivery to encephalopathies, enhancing therapeutic spread throughout a tissue, and increasing the number of patients that bene?t from treatment. This manuscript uses an innovative strategy to identify and modify brain ECM VLRs that are translatable to human protein mimetics and could be produced at a therapeutic scale. With key modi?cations, using ECM-targeting proteins that camp in the backyard of brain cells could result in enhanced demarcation and therapeutic delivery of drugs to normal and pathologic brain tissues.

References

2. Bonnans C, Chou J, Werb Z. Remodelling the extracellular matrix in development and disease. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2014 Dec;15(12):786-801.

3. Winkler J, Abisoye-Ogunniyan A, Metcalf KJ, Werb Z. Concepts of extracellular matrix remodelling in tumour progression and metastasis. Nature Communications. 2020 Oct 9;11(1):5120.

4. Umlauf BJ, Kuo JS, Shusta EV. Identification of Brain ECM Binding Variable Lymphocyte Receptors Using Yeast Surface Display. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2022;2491:235-48.

5. Han BW, Herrin BR, Cooper MD, Wilson IA. Antigen recognition by variable lymphocyte receptors. Science. 2008 Sep 26;321(5897):1834-7.

6. Herrin BR, Cooper MD. Alternative adaptive immunity in jawless vertebrates. The Journal of Immunology. 2010 Aug 1;185(3):1367-74.

7. Hong X, Ma MZ, Gildersleeve JC, Chowdhury S, Barchi Jr JJ, Mariuzza RA, et al. Sugar-binding proteins from fish: selection of high affinity “lambodies” that recognize biomedically relevant glycans. ACS Chemical Biology. 2013 Jan 18;8(1):152-60.

8. McKitrick TR, Hanes MS, Rosenberg CS, Heimburg-Molinaro J, Cooper MD, Herrin BR, et al. Identification of glycan-specific variable lymphocyte receptors using yeast surface display and glycan microarrays. Immune Receptors: Methods and Protocols. 2022:73-89.

9. Umlauf BJ, Clark PA, Lajoie JM, Georgieva JV, Bremner S, Herrin BR, et al. Identification of variable lymphocyte receptors that can target therapeutics to pathologically exposed brain extracellular matrix. Science Advances. 2019 May 15;5(5):eaau4245.

10. Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: from phenomenology to molecular understanding in less than a decade. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2007 Nov;8(11):931-7.

11. Saftig P, Klumperman J. Lysosome biogenesis and lysosomal membrane proteins: trafficking meets function. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2009 Sep;10(9):623-35.

12. Crotzer VL, Blum JS. Autophagy and its role in MHC-mediated antigen presentation. The Journal of Immunology. 2009 Mar 15;182(6):3335-41.

13. Umlauf BJ, Chung CY, Brown KC. Modular Three-component Delivery System Facilitates HLA Class I Antigen Presentation and CD8+ T-cell Activation Against Tumors. Molecular Therapy. 2015 Jun 1;23(6):1092-102.

14. Soto-Avellaneda A, Morrison BE. Signaling and other functions of lipids in autophagy: a Review. Lipids in Health and Disease. 2020 Dec;19:214.

15. Chaudhary N, Gomez GA, Howes MT, Lo HP, McMahon KA, Rae JA, et al. Endocytic crosstalk: cavins, caveolins, and caveolae regulate clathrin-independent endocytosis. PLoS Biology. 2014 Apr 8;12(4):e1001832.

16. Cilliers C, Menezes B, Nessler I, Linderman J, Thurber GM. Improved tumor penetration and single-cell targeting of antibody–drug conjugates increases anticancer efficacy and host survival. Cancer Research. 2018 Feb 1;78(3):758-68.

17. Abbott NJ, Patabendige AA, Dolman DE, Yusof SR, Begley DJ. Structure and function of the blood–brain barrier. Neurobiology of Disease. 2010 Jan 1;37(1):13-25.

18. Prakash R, Carmichael ST. Blood–brain barrier breakdown and neovascularization processes after stroke and traumatic brain injury. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2015 Dec;28(6):556-64.

19. Minagar A, Alexander JS. Blood-brain barrier disruption in multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2003 Dec;9(6):540-9.

20. Starr JM, Farrall AJ, Armitage P, McGurn B, Wardlaw J. Blood–brain barrier permeability in Alzheimer's disease: a case–control MRI study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2009 Mar 31;171(3):232-41.

21. Sweeney MD, Sagare AP, Zlokovic BV. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2018 Mar;14(3):133-150.

22. Herrin BR, Alder MN, Roux KH, Sina C, Ehrhardt GR, Boydston JA, et al. Structure and specificity of lamprey monoclonal antibodies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008 Feb 12;105(6):2040-5.

23. Mariuzza RA, Velikovsky CA, Deng L, Xu G, Pancer Z. Structural insights into the evolution of the adaptive immune system: the Variable Lymphocyte Receptors of Jawless Vertebrates. Biological Chemistry. 2010;391:753-60.

24. Steiner D, Forrer P, Plückthun A. Efficient selection of DARPins with sub-nanomolar affinities using SRP phage display. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2008 Oct 24;382(5):1211-27.

25. Umlauf BJ, Mix KA, Grosskopf VA, Raines RT, Shusta EV. Site-specific antibody functionalization using tetrazine–styrene cycloaddition. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2018 Apr 25;29(5):1605-13.

26. Umlauf BJ, Shusta EV. Site-Directed Modification of Yeast-Produced Proteins Using Expressed Protein Ligation. Expressed Protein Ligation: Methods and Protocols. 2020:221-33.