Abstract

Coarctation of the aorta (CoA) is a congenital narrowing of the thoracic aorta, most often at the isthmus near the ductus arteriosus. It accounts for 5–8% of congenital heart defects and can present at any age. While early diagnosis in infancy is ideal, delayed presentations in adolescence or adulthood remain significant. Contemporary diagnostic tools—including echocardiography, CT angiography, and MRI—enable accurate anatomic assessment. Management has evolved from open surgery to include catheter-based interventions, especially in older children and adults. Lifelong follow-up is essential due to risks of restenosis, hypertension, and aortic aneurysm formation. This communication outlines key aspects of CoA diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up, with reference to current guidelines and literature.

Keywords

Coarctation of the aorta, Congenital heart disease, Aortic narrowing, Balloon angioplasty, Aortic stenting, Hypertension

Introduction

Coarctation of the aorta (CoA) is a congenital cardiovascular anomaly characterized by a discrete or tubular narrowing of the thoracic aorta, most commonly located distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery near the site of the ductus arteriosus (aortic isthmus). It accounts for approximately 5–8% of all congenital heart defects and has an estimated incidence of 3–4 per 10,000 live births [1,2]. CoA frequently occurs in association with other congenital anomalies, including bicuspid aortic valve (present in over 50% of cases), ventricular septal defect, and more complex syndromes such as Turner syndrome and Shone’s complex [3,4].

The pathophysiology of CoA results in a significant pressure gradient across the narrowed segment, leading to upper extremity hypertension and lower extremity hypoperfusion. Over time, compensatory mechanisms such as collateral vessel formation may mask symptoms, particularly in milder cases, leading to delayed diagnosis well into adolescence or adulthood [5]. If left untreated, CoA can result in serious complications including premature coronary artery disease, heart failure, aortic rupture, aortic aneurysm, intracranial hemorrhage, and sudden cardiac death [6,7].

While early detection and surgical repair in infancy can significantly reduce morbidity and mortality, late presentations continue to occur, particularly in resource-limited settings or in patients with mild forms of the disease. With the advent of advanced non-invasive imaging modalities—such as echocardiography, computed tomography angiography (CTA), and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA)—the diagnosis and anatomical characterization of CoA has become more accurate and accessible across age groups [8,9].

Management options have evolved significantly over recent decades. Surgical repair remains the treatment of choice in neonates and young infants, whereas catheter-based interventions, including balloon angioplasty and endovascular stenting, are increasingly favored in older children, adolescents, and adults due to reduced procedural morbidity and favorable long-term outcomes [10,11].

Despite these advances, patients with repaired CoA require lifelong follow-up due to the risk of late complications, including recoarctation, persistent hypertension, and aortic aneurysm formation [12]. This communication aims to provide an up-to-date overview of the clinical features, diagnostic evaluation, and current management strategies for CoA, with an emphasis on contemporary challenges in diagnosis and long-term surveillance.

Pathophysiology

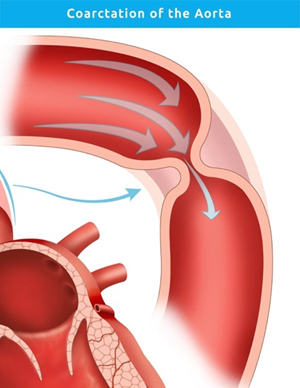

The exact embryologic mechanism of CoA remains debated, but proposed theories include aberrant ductal tissue migration into the aorta or impaired flow during fetal development [12]. Hemodynamically, the obstruction causes pressure overload proximal to the narrowing and hypoperfusion distally. This results in upper limb hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, and reduced lower limb pulses. Collateral circulation via intercostal and internal thoracic arteries may develop over time to compensate for the obstruction (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Image showing area of coarctation of aorta at the junction of left subclavian artery and descending thoracic aorta.

Clinical Presentation

Infants with critical CoA may present with heart failure, poor feeding, and differential cyanosis. In contrast, older children or adults often present with upper extremity hypertension, headaches, leg fatigue, or claudication. A classic finding is radio-femoral delay with diminished femoral pulses [13]. On auscultation, a systolic murmur may be heard over the back or left infraclavicular area.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Initial evaluation includes four-limb blood pressure measurements and physical examination. Transthoracic echocardiography is the first-line imaging modality in infants and children, providing information on the gradient across the coarctation and associated lesions. In adolescents and adults, cardiac MRI and CT angiography (CTA) offer superior spatial resolution and can delineate collateral circulation and associated aortic anomalies. A resting peak-to-peak systolic gradient >20 mmHg, or significant anatomical narrowing with collateral formation, is generally considered an indication for intervention [14].

Management Options

Surgical repair

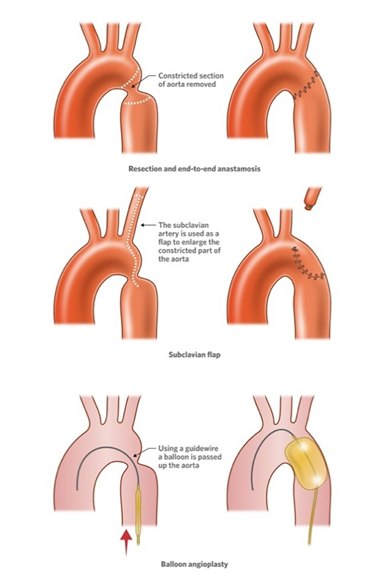

Surgical approaches include end-to-end anastomosis, extended end-to-end repair, patch aortoplasty, and subclavian flap repair (Figure 2). Surgery remains the standard of care for neonates and infants with discrete or complex coarctation. While surgical repair has excellent immediate outcomes, complications such as restenosis and aneurysm formation can occur in the long term.

Figure 2. Different approaches to tackle aortic coarctation.

|

Age Group |

Common Presenting Features |

Clinical Signs |

Complications if Untreated |

|

Neonates |

Poor feeding, tachypnea, lethargy |

Weak/delayed femoral pulses, differential cyanosis |

Heart failure, shock, metabolic acidosis |

|

Infants/Children |

Poor weight gain, irritability, murmur |

Upper-limb hypertension, radial-femoral delay |

Left ventricular hypertrophy, hypertension |

|

Adolescents |

Headaches, exercise intolerance, leg fatigue |

Systolic murmur (back), BP gradient |

Collateral circulation, aortic aneurysm |

|

Adults |

Refractory hypertension, claudication, murmur |

BP discrepancy, rib notching on imaging |

Aortic rupture/dissection, heart failure, stroke |

|

Treatment Modality |

Age Group (Preferred) |

Advantages |

Disadvantages/Risks |

|

Surgical Repair |

Neonates, infants |

Definitive correction, durable outcomes |

Restenosis, thoracic scarring, aneurysm |

|

Balloon Angioplasty |

Children (>6 months), adolescents |

Less invasive, good for recoarctation |

Risk of aneurysm, restenosis |

|

Stent Placement |

Adolescents, adults |

Excellent patency, reduced restenosis |

Vascular injury, need for reintervention |

|

Covered Stent |

Adolescents, adults |

Low aneurysm risk, seals intimal tears |

Larger sheath size, limited in small patients |

Catheter-based interventions

Balloon angioplasty was first introduced in the 1980s and remains an option, particularly in older children and adults [14]. However, restenosis and aneurysm formation were common with angioplasty alone (Figure 2). The addition of stenting, especially covered stents, has significantly improved outcomes in native and recurrent CoA, with lower rates of restenosis and fewer complications [15]. Current guidelines recommend stenting as the preferred intervention in patients older than 10–12 years with suitable anatomy.

Long-term outcomes and follow-up

Despite successful repair, long-term follow-up is crucial due to persistent or recurrent hypertension, aneurysm formation, and risk of late recoarctation [16]. Regular imaging with echocardiography, CTA, or MRI is recommended to monitor the aorta and detect complications [17]. Lifelong cardiology surveillance is advised, with attention to blood pressure control and screening for aortic valve and cerebral aneurysms, especially in those with bicuspid aortic valve [18]. Outcomes with open surgery are comparable to those with endovascular interventions, with the benefit of lowered morbidity in endovascular interventions. However, not all cases are amenable for endovascular interventions, and open surgery becomes the only option in several cases.

Special considerations

Women with repaired CoA are at increased risk of aortic dissection during pregnancy and should be monitored closely. Pre-pregnancy assessment of the aortic arch and blood pressure control are essential [19]. Exercise recommendations must be tailored; isometric and competitive sports are generally discouraged in patients with unrepaired or residual CoA [20].

Conclusion

Coarctation of the aorta remains a critical congenital cardiovascular lesion with lifelong implications. Advances in imaging and intervention have significantly improved outcomes, yet challenges in diagnosis and long-term management persist. Early recognition, individualized treatment, and rigorous follow-up are key to preventing long-term morbidity and mortality.

References

2. O'Sullivan JJ, Derrick G, Darnell R. Prevalence of hypertension in children after early repair of coarctation of the aorta: a cohort study using casual and 24-hour blood pressure measurement. Heart. 2002 Aug;88(2):163–6.

3. Campbell M. Natural history of coarctation of the aorta. Br Heart J. 1970 Sep;32(5):633–40.

4. Toro-Salazar OH, Steinberger J, Thomas W, Rocchini AP, Carpenter B, Moller JH. Long-term follow-up of patients after coarctation of the aorta repair. Am J Cardiol. 2002 Mar 1;89(5):541–7.

5. Sadler TW. Langman's Medical Embryology. 14th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2019.

6. Park MK. Pediatric Cardiology for Practitioners. 6th ed. India :Elsevier; 2014.

7. Kenny D, Hijazi ZM. Coarctation of the aorta: from fetal life to adulthood. Cardiol J. 2011;18(5):487–95.

8. Sachdeva R, Valente AM, Armstrong AK, Cook SC, Han BK, Lopez L, et al. Appropriate Use Criteria for Multimodality Imaging During the Follow-Up Care of Patients With Congenital Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee and Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, Heart Rhythm Society, International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and Society of Pediatric Echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Feb 18;75(6):657–703.

9. Gray RD, Parker KH, Quail MA, Taylor AM, Biglino G. A method to implement the reservoir-wave hypothesis using phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging. MethodsX. 2016 Aug 25;3:508–512.

10. Di Cesare E, Splendiani A, Barile A, Squillaci E, Di Cesare A, Brunese L, Masciocchi C. CT and MR imaging of the thoracic aorta. Open Med (Wars). 2016 Jun 23;11(1):143–151.

11. Baumgartner H, De Backer J. The ESC Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Adult Congenital Heart Disease 2020. Eur Heart J. 2020 Nov 14;41(43):4153–4.

12. Backer CL, Paape K, Zales VR, Weigel TJ, Mavroudis C. Coarctation of the aorta. Repair with polytetrafluoroethylene patch aortoplasty. Circulation. 1995 Nov 1;92(9 Suppl):II132–6.

13. Brown ML, Burkhart HM, Connolly HM, Dearani JA, Cetta F, Li Z, et al. Coarctation of the aorta: lifelong surveillance is mandatory following surgical repair. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Sep 10;62(11):1020–5.

14. Rao PS, Chopra PS. Role of balloon angioplasty in the treatment of aortic coarctation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991 Sep;52(3):621–31.

15. Forbes TJ, Kim DW, Du W, Turner DR, Holzer R, Amin Z, et al. Comparison of surgical, stent, and balloon angioplasty treatment of native coarctation of the aorta: an observational study by the CCISC (Congenital Cardiovascular Interventional Study Consortium). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Dec 13;58(25):2664–74.

16. Oliver JM, Gallego P, Gonzalez A, Aroca A, Bret M, Mesa JM. Risk factors for aortic complications in adults with coarctation of the aorta. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004 Oct 19;44(8):1641–7.

17. Choudhary P, Canniffe C, Jackson DJ, Tanous D, Walsh K, Celermajer DS. Late outcomes in adults with coarctation of the aorta. Heart. 2015 Aug;101(15):1190–5.

18. Asokan KL, Muraly N, Guo D, Shah DM, Martinez EC, Cervi E, et al. Bicuspid Aortic Valve in Heritable Thoracic Aortic Disease: Insights from the Montalcino Aortic Consortium. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2025 Nov 30:2025.11.26.25341124.

19. Canobbio MM, Warnes CA, Aboulhosn J, Connolly HM, Khanna A, Koos BJ, et al. Management of Pregnancy in Patients With Complex Congenital Heart Disease: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017 Feb 21;135(8):e50–e87.

20. Pelliccia A, Fagard R, Bjørnstad HH, Anastassakis A, Arbustini E, Assanelli D, et al. Recommendations for competitive sports participation in athletes with cardiovascular disease: a consensus document from the Study Group of Sports Cardiology of the Working Group of Cardiac Rehabilitation and Exercise Physiology and the Working Group of Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2005 Jul;26(14):1422–45.