Keywords

hemodialysis, Cognitive impairment, cognitive dysfunction

Introduction

Hemodialysis is the most common form of kidney replacement worldwide. It is expected that the acceptance rate of hemodialysis will continue to increase in the coming decades [1]. About 89% of dialysis patients worldwide receive hemodialysis. The majority of these patients are living in high-income countries or middle to high-income countries such as Brazil and South Africa. The conspicuous prevalence of long-term dialysis varies by region and is closely related to national income [2,3]. It shows that wealthier countries are more likely to have comprehensive dialysis registration offices than low-income countries. The mortality rate of dialysis patients is very high, especially in the first three months after the start of hemodialysis treatment. In those high-income countries, about a quarter of hemodialysis patients die within one year after starting the treatment, and this proportion is even higher in the low and middle-income countries [3]. For surviving patients, complications that affect their health are noteworthy, such as pain, infection, and bleeding related to vascular access puncture. In addition, some psychological complications have also received widespread attention in research, such as depression [4], sleep disorders [5], and cognitive impairment. Cognitive impairment refers to the impairment of cognitive function at different levels caused by various reasons, including but not limited to memory impairment, language impairment, visuospatial impairment, dyscalculia, executive dysfunction, and understanding and judgment impairment [6]. The impairment can be temporary or long-term, and in serious cases may lead to dementia. It not only affects one’s ability of daily life, but also may have a negative impact on his/her social function and mental health. Patients with impaired cognitive function may have difficulty in understanding medical advices, which may lead to inconsistent implementation of treatment plans, thus increasing the risk of lower compliance. Patients suffering from cognitive impairment have weaker self-care ability, fewer social activities and increased emotional problems, thus they may encounter more difficulties in daily life, which affect the quality of their life. Moreover, cognitive impairment may also increase the risk of additional medical treatment, thus increasing the cost thereof. Therefore, cognitive impairment in hemodialysis has gradually aroused extensive attention among researchers.

Findings of Previous Studies

In previous studies, we believe that more systematic evidence is still needed for cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients. Therefore, we previously published a systematic review on the prevalence of cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients [7], and our study was indexed up to December 1, 2022, with a final inclusion of 10 studies. Meta analysis of the results showed us that the prevalence of cognitive dysfunction in hemodialysis patients was 51% (95% CI: 0.33-0.69), and there were significant differences in age, gender, the number of diabetes patients, and the number of stroke patients between people with cognitive impairment and those without cognitive impairment. However, we are subject to some limitations in our study. Firstly, since the limited amount of data included in the study, we did not explore more the differences between assessment tools for different types of cognitive impairment. Secondly, we failed to further discuss some specific blood dialysis factors, such as dialysis methods (traditional dialysis and hemofiltration), dialysis dosage (spKt/v), and dialysate modification (such as dialysate cooling). Therefore, more evidence is needed for further discussion. We also failed to further explore the differences in the impact of these factors on cognitive impairment. Thirdly, due to the limited number of study objects included and the fact that they come from multiple regions, we were unable to further discuss the differences in cognitive impairment among different regions. Fourthly, we only discussed limited differential factors. These limitations have limited our further understanding of cognitive impairment in hemodialysis to some extent.

Summary of Newly-published Studies

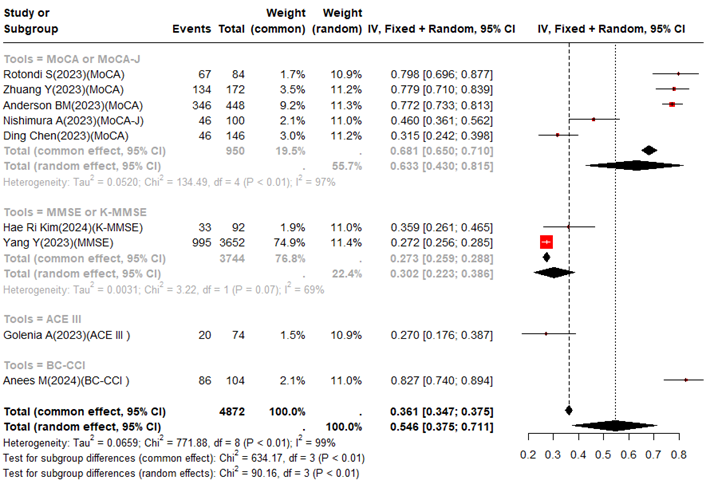

We notice that from 2023 to 2024, some researchers explored the prevalence of cognitive impairment in maintaining hemodialysis. We can see that there are differences in the assessment methods, disease duration, and the number of hemodialysis patients among different studies. Published from 7 countries, with 6 studies [8-13] from Asia and 3 studies [14-16] from Europe. In terms of assessment methods, they mainly involve Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA )[8,10,14,15], Montreal Cognitive Assessment Japanese (MoCA-J) [12], Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) [9], Korean Mini Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) [11], Brain Damage and Cognitive Change Index (BC-CCI) [13], and Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination III (ACE III) [16]. In the newly-published studies included, the reasons for the significant differences in the incidence of cognitive impairment among hemodialysis patients, in addition to differences in assessment methods, are as follows: 1) Most of the studies are single center studies, and the included cases are less than 200, resulting in sample size bias; 2) Even though these studies involve a significant range, only three of them [10,13,16] analyze multiple risk factors of cognitive impairment. However, since there are significant differences among different risk factors, it remains a serious challenge to analyze independent risk factors based on existing newly-published studies (Table 1). This also suggests that there is still a lack of sufficient attention to the study of cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients in existing studies. We extracted the number of patients with cognitive impairment and the number of hemodialysis patients from the newly-published studies for further meta-analysis. We used the heterogeneity index (I2) to assess heterogeneity among different studies. When I2>50%, we used a random effects model; when I2<50%, we used a fixed effects model. In our forest plot, we presented the results of both the fixed effects model and the random effects model. During analysis, we conducted subgroup analysis on the assessment methods. Due to the inclusion of less than 10 new articles, we failed to analyze the publication bias through funnel plots. The entire analysis process is described in R4.4.1 (https://cran.r-project.org/).

|

No |

Author |

Year |

Country |

Design |

Mean HD(m) |

Sample size |

CI |

Prevalence |

Tools |

Critical value |

|

1 |

Zhuang Y [8] |

2023 |

China |

Cross section |

>3 |

172 |

134 |

77.9 |

MoCA |

26 |

|

2 |

Yang Y [9] |

2023 |

China |

Cohort study |

|

3652 |

995 |

27.2 |

MMSE |

27 |

|

3 |

Ding Chen [10] |

2023 |

China |

Cross section |

0-60(54.8%) >60(45.2%) |

146 |

46 |

31.5 |

MoCA |

26 |

|

4 |

Hae Ri Kim [11] |

2024 |

Korea |

Cohort study |

CI:19.9 NCI:10.2 |

92 |

33 |

35.9 |

K-MMSE |

24 |

|

5 |

Nishimura A [12] |

2023 |

Japan |

Cross section |

87.6 |

100 |

46 |

46.0 |

MoCA-J |

26 |

|

6 |

Anees M [13] |

2024 |

Pakistan |

Cross section |

44.1 |

104 |

86 |

82.7 |

BC-CCI |

|

|

7 |

Rotondi S [14] |

2023 |

Italy |

Cross section |

46.0 |

84 |

67 |

79.8 |

MoCA |

26 |

|

8 |

Anderson BM [15] |

2023 |

UK |

Cohort study |

|

448 |

346 |

77.2 |

MoCA |

26 |

|

9 |

Golenia A [16] |

2023 |

Poland |

Cross section |

36.6 |

74 |

20 |

27.0 |

ACE III |

88 |

|

Note: Mean HD refers to the average duration of hemodialysis. Mean HD (m) refers to the average dialysis time, unit in months. |

||||||||||

The overall results were summarized by using a random effects model and showed in the previously-published studies. The prevalence of cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients was 54.6% (95% CI: 37.5-71.1%). In the newly-published studies, the overall prevalence was similar to our previous studies, which had a prevalence of 51% (95% CI: 33-69%). In addition, in this newly-published study, we discussed the impact of different assessment tools on the prevalence of cognitive impairment. The prevalence of cognitive impairment assessed by MoCA or MoCA-J was 63.3% (95% CI: 43.0-81.5%), the prevalence of cognitive impairment assessed by MMSE or K-MMSE was 30.2% (95% CI: 22.3-38.6), the prevalence of cognitive impairment assessed by ACE III was 27.0% (95% CI: 17.5-37.8), and the prevalence of cognitive impairment assessed by BC-CCI was 82.7% (95% CI: 74.0-89.4). We found that there seem to be significant differences based on the same evaluation tool (Figure 1). We also found the following limitations in the newly-published studies: (1) Further discussion on the impact of age, dialysis duration, comorbidities, family environment, sample volume and regional differences on cognitive impairment. (2) There was no strict dialysis method (traditional dialysis and hemofiltration) and dialysis dose (spKt/v) in some original studies, hence more evidence is needed to discuss the impact of these factors on cognitive impairment.

Figure 1 Incid ence of cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients in a newly published study.

Future Prospects

The above analysis shows that cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients has a very high prevalence rate, which requires more attention in clinical practice and the development of efficient risk screening strategies and specific prevention plans. Unfortunately, there is still a lack of effective and efficient prediction tools for cognitive impairment in hemodialysis, especially when it serves as a maintenance treatment process. Therefore, it is of great significance to clinically study real-time prediction tools for cognitive impairment in this group of people. At present, as machine learning gradually draws more and more attention from researchers in the field of medicine, it can recognize the high-dimensional data to construct differential diagnosis of diseases, prediction of disease progression, prediction of treatment response, prediction of medical trends, definition of disease subtypes, biopharming, etc. It seems to have ideal effects [17,18]. Besides, machine learning can not only be implemented based on common interpretable clinical features, but also efficiently deal with medical images [19]. At present, some researchers have explored the application prospects of machine learning in hemodialysis. Meng et al. [20] reviewed predictive models for arteriovenous fistulas in hemodialysis, and they found that machine learning based methods have greater predictive value than scoring tools. Sandys et al. [21] reviewed the current application status of artificial intelligence in volume maintenance for hemodialysis patients. Chaudhry et al. [22] reviewed the prediction of hypotension during hemodialysis in patients. In addition, some studies have explored the use of machine learning to predict mortality in hemodialysis patients [23,24], however, further exploration is still needed for predicting cognitive impairment. Therefore, in the future research, we should try to construct methods based on machine learning, screen the effective predictors of cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients, and build real-time, simplified, and efficient prediction tools. In this way, specific prevention plans can be developed to reduce the incidence of cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients and improve their living quality in the rest of their life as well. In addition, we have some suggestions for future machine learning: (1) Team building, which is a process that requires interdisciplinary collaboration. Therefore, we should consider forming a team consisting of psychologists, neurologists, and data scientists before conducting research; (2) In order to discuss the robustness and applicability of a model, we need to fully assess the required number of cases and conduct multicenter studies before constructing the model; (3) We need to collect efficient and low-cost predictive factors to ensure the accuracy of the model; (4) For the missing value and abnormal value of predictive factors, we need to consider choosing reasonable processing methods, and even consider the results of different processing methods. (5) In the screening stage of predictive factors, we should compare and combine multiple methods; (6) In terms of model selection, we need to take into account the interpretability of models. Some models (logistic regression, decision tree) have good interpretability and poor accuracy, while others have poor interpretability (support vector machine, XGBoost, deep learning) and good accuracy [25]. When these two types of models have similar accuracy, we recommend using the models with better interpretability, which are more suitable for the development of the suggested scoring tools; (7) In the process of model construction, we need to fully assess the goodness of fit of models to avoid overfitting and underfitting as much as possible; (8) In the model validation phase, we need to adopt multicenter validation to the greatest extent; (9) We also need to pay attention to the updating of models.

References

2. White SL, Chadban SJ, Jan S, Chapman JR, Cass A. How can we achieve global equity in provision of renal replacement therapy? Bull World Health Organ. 2008 Mar;86(3):229-37.

3. Himmelfarb J, Vanholder R, Mehrotra R, Tonelli M. The current and future landscape of dialysis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020 Oct;16(10):573-585.

4. Li Y, Zhu B, Shen J, Miao L. Depression in maintenance hemodialysis patients: What do we need to know? Heliyon. 2023 Aug 24;9(9):e19383.

5. Kraus MA, Fluck RJ, Weinhandl ED, Kansal S, Copland M, Komenda P, et al. Intensive Hemodialysis and Health-Related Quality of Life. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016 Nov;68(5S1):S33-S42.

6. Montine TJ, Bukhari SA, White LR. Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults and Therapeutic Strategies. Pharmacol Rev. 2021 Jan;73(1):152-62.

7. Liu J, Chen K, Chen J, Fu L, Zhang W, Lin J, et al. Incidence and risk factors of cognitive dysfunction in hemodialysis patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Dial. 2023 Sep-Oct;36(5):358-65.

8. Zhuang Y, Wang X, Zhang X, Fang Q, Zhang X, Song Y. The relationship between dietary patterns derived from inflammation and cognitive impairment in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Front Nutr. 2023 Aug 3;10:1218592.

9. Yang Y, Long Y, Yuan J, Zha Y. U-shaped association of serum magnesium with mild cognitive impairment among hemodialysis patients: a multicenter study. Ren Fail. 2023 Dec;45(1):2231084.

10. Chen D, Xiao C, Xiao W, Lou L, Gao Z, Li X. Prediction model for cognitive impairment in maintenance hemodialysis patients. BMC Neurol. 2023 Oct 12;23(1):367.

11. Kim HR, Kim MJ, Jeon JW, Ham YR, Na KR, Park H, et al. Association between Serum GDF-15 and Cognitive Dysfunction in Hemodialysis Patients. Biomedicines. 2024 Feb 3;12(2):358.

12. Nishimura A, Hidaka S, Kawaguchi T, Watanabe A, Mochida Y, Ishioka K, et al. Relationship between Lower Extremity Peripheral Arterial Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment in Hemodialysis Patients. J Clin Med. 2023 Mar 9;12(6):2145.

13. Anees M, Pervaiz MS, Aziz S, Elahi I. Predictors of cognitive impairment and its association with mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients: A prospective follow-up study. Pak J Med Sci. 2024 May-Jun;40(5):933-8.

14. Rotondi S, Tartaglione L, Pasquali M, Ceravolo MJ, Mitterhofer AP, Noce A, et al. Association between Cognitive Impairment and Malnutrition in Hemodialysis Patients: Two Sides of the Same Coin. Nutrients. 2023 Feb 4;15(4):813.

15. Anderson BM, Qasim M, Correa G, Evison F, Gallier S, Ferro CJ, et al. Cognitive Impairment, Frailty, and Adverse Outcomes Among Prevalent Hemodialysis Recipients: Results From a Large Prospective Cohort Study in the United Kingdom. Kidney Med. 2023 Feb 9;5(4):100613.

16. Golenia A, Żołek N, Olejnik P, Żebrowski P, Małyszko J. Patterns of Cognitive Impairment in Hemodialysis Patients and Related Factors including Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Med. 2023 Apr 25;12(9):3119.

17. Adlung L, Cohen Y, Mor U, Elinav E. Machine learning in clinical decision making. Med. 2021 Jun 11;2(6):642-65.

18. Rathore AS, Nikita S, Thakur G, Mishra S. Artificial intelligence and machine learning applications in biopharmaceutical manufacturing. Trends Biotechnol. 2023 Apr;41(4):497-510.

19. Dayarathna S, Islam KT, Uribe S, Yang G, Hayat M, Chen Z. Deep learning based synthesis of MRI, CT and PET: Review and analysis. Med Image Anal. 2024 Feb;92:103046.

20. Meng L, Ho P. A systematic review of prediction models on arteriovenous fistula: Risk scores and machine learning approaches. J Vasc Access. 2024 Apr 24:11297298241237830.

21. Sandys V, Sexton D, O'Seaghdha C. Artificial intelligence and digital health for volume maintenance in hemodialysis patients. Hemodial Int. 2022 Oct;26(4):480-495.

22. Chaudhry TZ, Yadav M, Bokhari SFH, Fatimah SR, Rehman A, Kamran M, et al. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Predicting Intradialytic Hypotension in Hemodialysis Patients: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2024 Jul 25;16(7):e65334.

23. Komaru Y, Yoshida T, Hamasaki Y, Nangaku M, Doi K. Hierarchical Clustering Analysis for Predicting 1-Year Mortality After Starting Hemodialysis. Kidney Int Rep. 2020 May 23;5(8):1188-1195.

24. Ohashi K, Sato M, Fujiwara K, Tanikawa T, Morii Y, Ogasawara K. Spatial accessibility of home visiting nursing: An exploratory ecological study. Health Sci Rep. 2024 Sep 16;7(9):e70078.

25. Gunning D, Stefik M, Choi J, Miller T, Stumpf S, Yang GZ. XAI-Explainable artificial intelligence. Sci Robot. 2019 Dec 18;4(37):eaay7120.