Abstract

Purpose: The 6-minute walk test (6MWT) and the 2-minute walk test (2MWT) are common assessments of walking performance. The study aims to investigate the walking performance in elderly individuals living either in the community or in a nursing home.

Methods: A convenience sample of 77 elderly individuals was assessed with both tests to investigate the test-retest reliability (ICC), to compare the performance between community and nursing home residents (ANOVA) and to study the correlation (r) between participants’ performance on both tests with age and physical activity.

Results: The 6MWT and 2MWT showed excellent test-retest reliability (ICC=0.99). There was no significant difference in walking speed between the 6MWT and the 2MWT (p=0.320) and a strong correlation was observed between both tests (r=0.96, p<0.001). ROC curve analysis showed an excellent discrimination for both tests between community and nursing home residents, using cutoff values of 386.5 m for the 6MWT and of 132.5 m for the 2MWT. Moderate correlations were observed between walking distances and age (r=-0.61 for 2MWT and r=-0.69 for 6MWT, p<0.001).

Conclusions: The 2MWT demonstrated a high test-retest reliability, no significant difference in walking speed, strong correlation and a comparable cutoff value to those of the 6MWT for assessing walking performance in elderly participants. Similar results highlight the clinical utility of the 2MWT as a time-effective alternative to the 6MWT to evaluate walking deterioration in elderly individuals.

Keywords

Walk test, Aged, Nursing homes, Walking

Key Summary Points

Aim: To compare walking performance in elderly individuals living either in the community or in a nursing home using the 6-minute walk test (6MWT) and the 2-minute walk test (2MWT).

Findings: The 2MWT showed high test-retest reliability, no significant differences in walking speed, a strong correlation and comparable cutoff values to the 6MWT for evaluating walking performance in elderly.

Message: The 2MWT is comparable to the 6MWT in assessing walking deterioration among older adults, offering a time-efficient alternative to the 6MWT.

Introduction

In 2021, older adults were making up about 13.5% of the global population and projections indicated that by 2030, one in six people would be aged 60 years or more [1]. Aging is associated with a progressive decline in exercise capacity, along with changes in physical function and walking ability [2], which can influence the performance of daily activities and the preservation of personal independence [3]. Walking limitation is highly prevalent among older adults, with rates ranging from 58.1% to 93.2% [4], and it is a risk factor for functional dependence in community-dwelling older adults [5]. Moreover, improving walking ability significantly enhances various aspects of health-related quality of life, including physical, emotional, and social well-being [6].

Walking performance can reliably be assessed with the 6-minute walk test (6MWT), a simple and inexpensive submaximal test of walking capacity and cardiovascular fitness validated in people with various conditions [7,8]. In healthy elderly people, the 6MWT has shown a moderate to strong correlation (0.71<r<0.82, p<0.001) with a cardiopulmonary exercise test on treadmill. The 6MWT has also demonstrated a high test-retest reliability (ICC=0.96) in elderly people with intellectual disabilities [9]. It is a practical alternative to laboratory-based assessments and better reflects real-life functional abilities [10]. Additionally, the 6MWT is used as an assessment tool for older populations [10] and is included in the Senior Fitness Test to evaluate functional fitness in older adults [11,12].

However, the 6MWT is time-consuming for clinicians and may be impossible for older adults who have severe walking limitations [13]. The 2-minute walk test (2MWT) has been proposed as a shorter alternative, following a similar protocol and offering comparable benefits to the 6MWT [14]. Studies have shown significant and strong correlations between the distances covered in the 6MWT and the 2MWT among healthy older adults (r=0.76, p<0.05) [15] and in residents of long-term care facilities (r=0.93, p<0.05) [13]. The 2MWT has demonstrated excellent test-retest reliability in long-term care residents (ICC>0.94) [13] and in healthy older adults (ICC=0.94) [15].

Research indicates that older adults living in nursing homes perform significantly lower on physical assessments compared to those living in the community [16]. This difference is attributed to better lower-limb function, balance and mobility, which impact walking performance in community-dwelling elderly [13,16]. Comparing walking performance between living environments can help determining target values for elderly living in nursing homes or cut-off values that allow an easier interpretation in clinical practice than age- or gender-matched normative values. For example, cut-off values below which a clinically meaningful walking limitation is declared for the 6MWT are defined at 350 m for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [17], 300 m for heart failure [18] and 304 m for stroke [19]. While such cutoff values can be used to identify individuals at higher risk of poor functional outcomes, no cut-off value has been established to differentiate walking performance between community-dwelling elderly and those in nursing homes.

The study aims to investigate walking performance in elderly individuals living either in the community or in a nursing home. Specifically, the study aims to (1) assess the test-retest reliability of the 6MWT and 2MWT in elderly individuals, (2) compare walking performance in elderly individuals living in the community and in nursing homes using cut-off values, and (3) study the correlation between participants’ performance on both tests with age and physical activity.

Method

Participants

A convenience sample of 77 elderly individuals was recruited, including participants living in the community or in a nursing home. Participants had to be aged 60 or older, able to follow test instructions and without any active neuromuscular, musculoskeletal, or acute cardiopulmonary conditions that limited their walking ability. Participants were allowed to use their usual technical walking aids as described in ATS recommendations [20]. Seven participants (17%) used a walker or a crutch in the nursing home group, while no technical aid was used in the community group. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital. The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in (Table 1).

|

|

All participants (n=77) |

Community-dwelling group (n=37) |

Nursing home group (n=40) |

|

Age, years |

74.7 (7.72) |

70.1 (6.65) |

79.1 (5.98) |

|

Female, n (%) |

52 (67.5%) |

21 (56.8%) |

31 (77.5%) |

|

BMI, kg/m² |

24.9 (4.63) |

24.5 (3.63) |

25.2 (5.40) |

|

IPAQ-SF, MET.min/week |

2260 (1790) |

3060 (1790) |

1520 (1460) |

|

IPAQ-SF: International Physical Activity Questionnaire – Short Form |

|||

Procedures

Demographic data, including gender, age, height, and weight was gathered before the walking tests. Physical activity was assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire – Short Form (IPAQ-SF). Participants were instructed to wear comfortable clothing, usual footwear and avoid doing vigorous exercises or eating heavy meals within 2 hours before the walking tests. The participants were instructed to sit near the starting point and rest for 15 minutes before each test.

Six-minute and two-minute walk tests

The 6MWT and the 2MWT were administered according to the American Thoracic Society guidelines [20,21] over a flat 30-meter course. Participants were instructed to walk as far as they could and were allowed to slow down or stop and continue to walk again after they recovered during the test period. When 1 minute had elapsed, the evaluator provided standard encouragement with an even tone such as “You are doing well; you have 5-, 4-, 3-, 2-, or 1-minute left”. Subject stopped at 2 minutes or 6 minutes, and the distance covered was measured to the nearest meter. All participants performed both walk tests without prior trial. The order of the 2MWT and the 6MWT was randomly assigned. The walking speed was computed for both tests as the distance walked divided either by 120 or by 360 seconds.

Reliability

To investigate test-retest reliability, participants repeated the 2MWT and 6MWT after 1 to 3 days. Both walking tests were repeated by the same evaluator, reversing the order of the tests between sessions. To minimize influence of the first assessment on the second, participants were not informed of the test results until they had completed the test in the second session.

Data analysis

Demographic characteristics were compared between the community-dwelling and the nursing home groups using the Mann-Whitney U test for age, BMI, and level of physical activity and the Chi-square test for sex.

A two-way ANOVA was conducted to assess the effects of group (nursing home vs. community-dwelling) and test session (first and second tests) on walking distance for the 6MWT and 2MWT. The test-retest reliability of the 6MWT and 2MWT was assessed with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC2,1) using a two-way random model with absolute agreement. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were computed between the 2MWT and the 6MWT distances.

A two-way ANOVA was conducted to assess the effects of group (nursing home vs. community-dwelling) and test type (2MWT vs. 6MWT) on walking speed. An independent sample t-test was used to compare walking speed and distance between the community-dwelling and the nursing home groups.

A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was established to determine the most sensitive and specific cutoff value for the 6MWT and the 2MWT to distinguish walking performance between community-dwelling participants and nursing home residents. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was calculated to determine the quality of the classifier defined with the cutoff value [22].

Spearman correlation coefficients were computed between walked distances and age or physical activity level, in both the community-dwelling and nursing home groups. The strength of relationships between variables was classified as either absent or weak (r<0.25), weak to moderate (0.25 ≤ r<0.5), moderate to strong (0.5 ≤ r<0.75), or strong (r ≥ 0.75) [23]. The significance level was set to 0.05 for all statistical analyses. All analyses were performed using R (version 4.0.5; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Seventy-seven participants were assessed in the study, including 37 community-dwelling individuals and 40 nursing home residents. Nursing home residents were significantly older (p<0.001) and had lower values for physical activity level (p<0.001) compared to community-dwelling participants. Sex proportion and BMI were not different between groups.

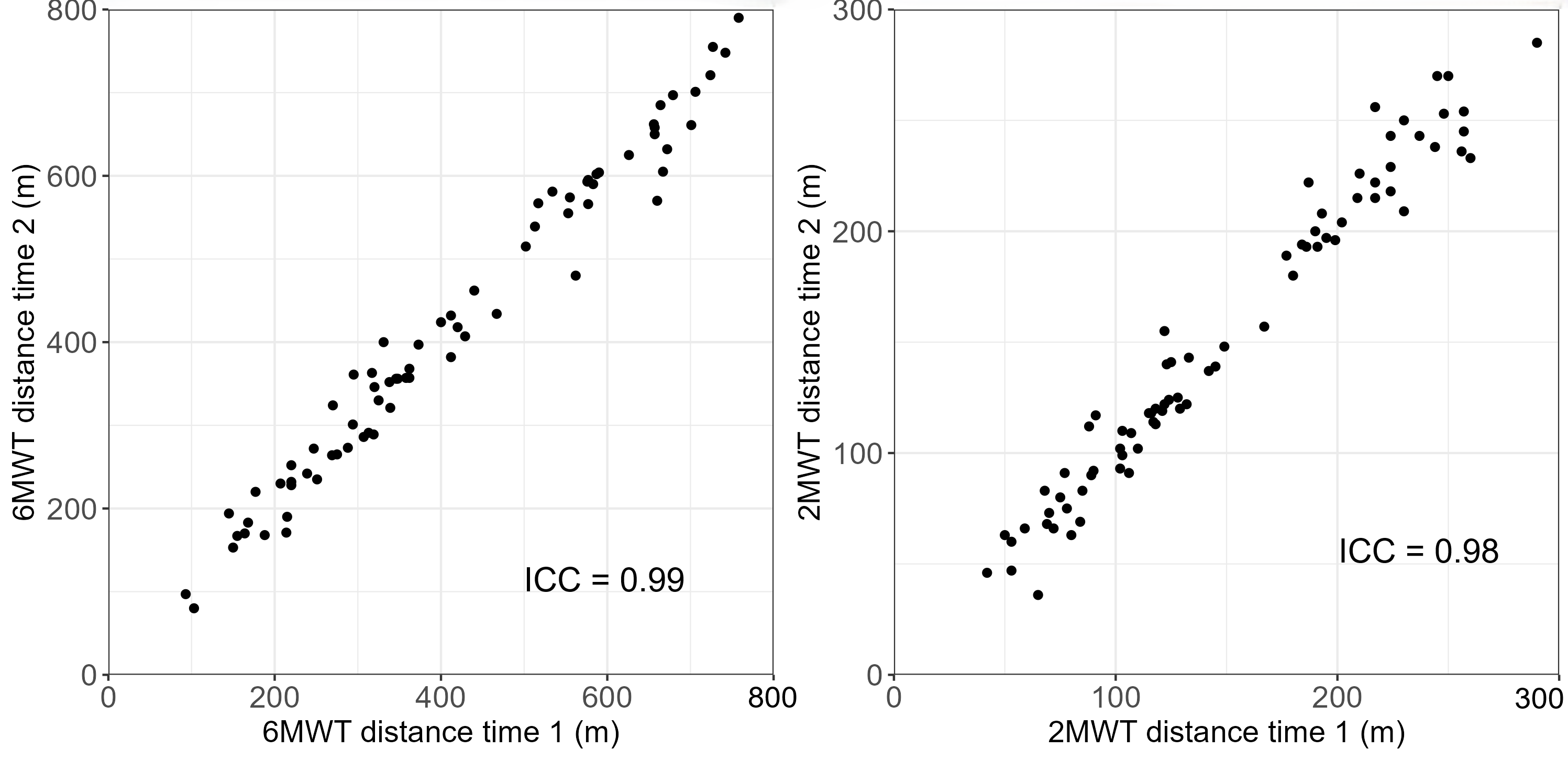

All the participants were re-assessed after a delay of 1 to 3 days. The mean (SD) distances walked were 429 (200.0) m for the first and 433 (196.0) m for the second 6MWT and were 149 (65.9) m and 151 (67.8) m for the 2MWT, respectively, indicating no significant difference between assessments for both tests (both p>0.637). As shown in Figure 1, the test-retest reliability for walking distance was excellent, with an ICC of 0.99, (95%CI: 0.98-0.99) for the 6MWT and 0.98 (95% CI: 0.97-0.99) for the 2MWT.

Figure. 1 Distance walked during the first and second assessment with the 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) and with the 2-minute walk test (2MWT). The Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) shows excellent test-retest reliability for both tests in all participants.

The 2-way ANOVA showed no significant difference between the 6MWT and the 2MWT indicating that all participants walked with the same speed during both tests (p=0.320). The Pearson correlation coefficient between the 6MWT and 2MWT distances measured in the whole sample was 0.96 (p<0.001), suggesting a strong correlation between both tests whatever the participant’s living environment.

Walking performance as well as comparisons between nursing home residents and community-dwelling participants on the 6MWT and 2MWT, are reported in Table 2. Community-dwelling participants showed better walking performance than nursing home residents both on the 6MWT and on the 2MWT (all p-values<0.001). The mean difference in walking distance was 340.8 m (95% CI, 293.1 to 388.4) for the 6MWT and 112.4 m (95% CI, 96.6 to 128.3) for the 2MWT. The mean difference in walking speed was 0.95 m/s (95% CI, 0.74 to 1.68) for the 6MWT and 0.94 m/s (95% CI, 0.79 to 1.73) for the 2MWT.

|

|

|

Community (n=37) |

Nursing home (n=40) |

Community vs. nursing home |

|

Distance (m) |

6MWT |

606 (121) |

266 (83.8) |

<0.001 |

|

2MWT |

207 (40.9) |

94.7 (26.6) |

<0.001 |

|

|

Speed (m/s) |

6MWT |

1.68 (0.335) |

0.738 (0.233) |

<0.001 |

|

2MWT |

1.73 (0.341) |

0.789 (0.221) |

<0.001 |

A ROC curve analysis indicated that both the 6MWT and 2MWT effectively discriminated between community-dwelling and nursing home participants based on walking performance (Figure 2). The optimal cutoff values were determined to be 386.5 m, with a sensitivity of 0.95 and specificity of 0.97 for the 6MWT, and 132.5 m, with a sensitivity of 0.98 and specificity of 0.95 for the 2MWT. The AUC was 0.99 for both the 6MWT and 2MWT, demonstrating excellent discrimination between the community and nursing home groups [22].

Figure. 2 Walked distance as a function of age for the 6MWT (A) and 2MWT (B) for participants living at home (open symbols) or in a nursing home (plain symbols). The optimal threshold (dashed line) differentiates both groups of participants. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve for the 6MWT (C) and 2MWT (D) to classify walking performance between the community-dwelling and nursing home group.

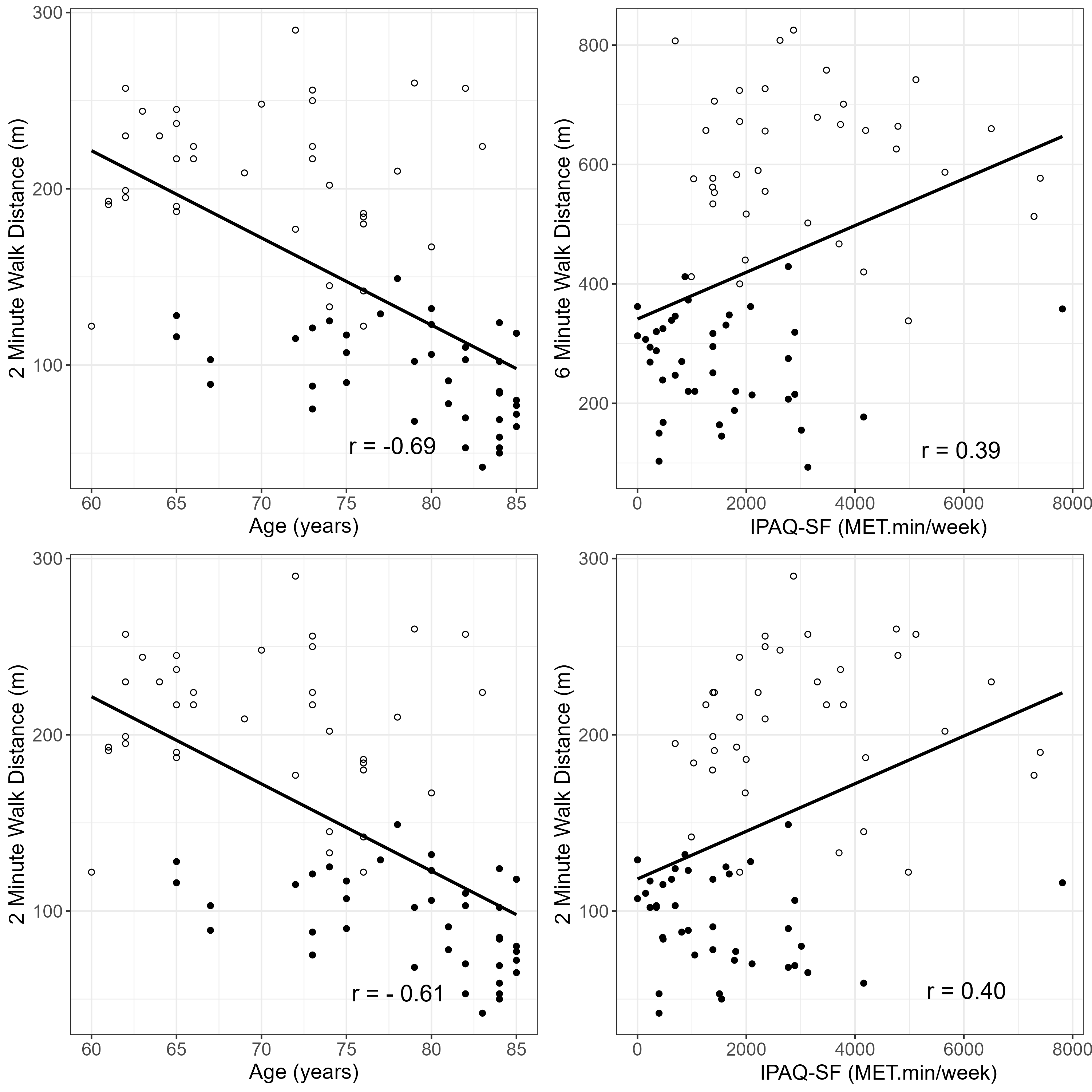

The relationships between walking distance, age, and level of physical activity are presented in Figure 3. Moderate to strong significant correlations were observed between walking distances and age (p<0.001) where nursing home residents were significantly older than the community-dwelling participants (mean age of 79 and 70 years, respectively, p<0.001). Levels of physical activity showed weak to moderate significant correlations with walking distance where community-dwelling participants demonstrated a two-fold level of physical activity compared to nursing home residents (3060 vs. 1520 MET.min/week, respectively, p<0.001).

Figure 3. Correlation between walking distances and participants’ age and level of physical activity for the 6MWT (top row) and the 2MWT (bottom row) for community-dwelling participants (open symbols) and for nursing home residents (plain symbols) including linear regressions (plain line).

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the assessment of walking performance among community-dwelling elderly individuals and nursing home residents, revealing several key insights. Both the 6MWT and 2MWT demonstrated high test-retest reliability in elderly participants. The 6MWT and 2MWT were strongly correlated in assessing walking performance, comparable in measuring walking speed, and showed similar relationships with age and physical activity levels in elderly participants. Therefore, the 2MWT is equivalent to the 6MWT and can effectively replace it in assessing walking performance in elderly individuals living in the community and in nursing homes.

Both the 6MWT and 2MWT demonstrated high test-retest reliability in elderly people who could walk independently both in community and nursing home, with ICC values of 0.99 and 0.98, respectively. This indicates that both tests consistently yield reproducible measurements in elderly people in both settings. These findings align with previous studies, which reported an excellent reliability of the 6MWT in elderly people with intellectual disability (ICC = 0.96) [9] and of the 2MWT in elderly people in long term care facility (ICC>0.94) [24] or in community (ICC=0.94) [15].

Despite studies suggesting that a familiarization test should be administered due to a learning effect between tests in young and healthy participants [21,25], the present study found no significant difference between the first and second assessments of both the 6MWT and 2MWT (both p>0.637). Similarly, previous research has shown that the learning effect is less pronounced in cardiopulmonary patients who walk less than 300 meters [26] or in individuals with lower cardiorespiratory function [27]. Although the participants in the current study were apparently healthy according to the inclusion criteria, elderly participants demonstrated lower walking performance compared to a young, healthy population, making any performance improvements in a second test less meaningful. Therefore, these results suggest that administering the walking test on one occasion only is sufficient in measuring walking performance in elderly individuals in community and nursing home settings.

There was a strong correlation between the distances covered in the 6MWT and the 2MWT among elderly participants (r=0.955). This result aligns with previous studies involving frail elderly individuals with dementia (r=0.92) [24] and older adults in residential care facilities (r=0.93) [13]. Additionally, no significant difference of speed was observed between the two assessments, indicating that participants did not adapt their spontaneous walking speed to the exercise duration for the 6MWT and 2MWT (p=0.320). This finding is consistent with a previous study on healthy adults, which also reported no difference in walking speed between the 2MWT and 6MWT (r=0.94) [28]. These findings support the use of the 2MWT as a reliable alternative to the 6MWT for assessing walking performance in older adults residing in both community and nursing home settings. In addition, the 2MWT is less time consuming than the 6MWT and easier to use in busy clinics which makes it a more practical alternative in resource-limited settings. Nevertheless, although the correlation between the 2MWT and the 6MWT is strong and statistically significant, shorter tests may overestimate walking endurance [29]. Moreover, other functional assessments such as the Timed Up and Go Test [30], the 30 Second Sit to Stand Test [31] or the Short Physical Performance Battery [32], could provide a broader functional assessment framework.

The findings demonstrated that the walking performance of both the 6MWT and 2MWT was significantly lower in participants living in a nursing home compared to older adults dwelling in the community (all p-values <0.001). The 6MWT distance achieved by community participants in this study (606 m) was very similar to the distance reported for Belgian older adults of 603 m [33] but was higher than the range reported for community-dwelling adults aged 60–89 years (392–572 m) in another study [34]. The differences in distance walked may be attributed to the varying health conditions and comorbidities of elderly participants in previous studies compared to healthy elderly participants in this study.

The ROC curve analysis demonstrated that both the 6MWT and 2MWT are effectively distinguished between the two groups, community or nursing home, with only 3 out of 77 participants (3.9%) misclassified. The AUC was greater than 0.94 for both tests, indicating outstanding discrimination between both groups [22]. The findings of this study suggest that cutoff values of 386.5 m for the 6MWT and 132.5 m for the 2MWT could serve as practical thresholds to assess walking performance in elderly people and identify individuals who may be at increased risk of health consequences related to a walking limitation. The threshold value of 386.5 m for the 6MWT was higher than the values reported in previous studies, where a cutoff 350 m was reported for COPD [17], 300 m for heart failure [18], and 304 m for stroke [19]. The difference in the 6MWT cutoff values between our findings and previous studies may be attributed to the characteristics of this study’s participants, who were healthy older adults without stroke or cardiorespiratory diseases. Along with reference values, these thresholds may facilitate the early identification of walking deterioration and support gait rehabilitation by providing training goals to limit further health deterioration in older adults with walking limitations.

Findings from this study are consistent with previous research, indicating that age is the most important factor influencing walking distance in healthy individuals, with the effect becoming more pronounced in those over 60 years of age [35,36]. Physical activity levels showed weak to moderate but significant correlations with walking distance in both tests across all elderly participants (r=0.39 for the 6MWT and r=0.40 for the 2MWT). Previous studies have reported that self-reported physical activity did not influence walking distance [35,37]. This difference may be due to the distinct and wide range of physical activity levels between community-dwelling and nursing home residents in this study. Nevertheless, the consistent relationship between walking distance in both tests and factors such as age and physical activity levels suggest that the 6MWT and 2MWT are not only comparable in measuring walking performance but also in reflecting the impact of age and physical activity on walking ability.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the relatively small sample size and the fact that participants were volunteers and relatively healthy older adults may not reflect the characteristics of individuals living in geriatric nursing homes or community dwellings. This may introduce selection bias, as volunteers may present a higher functional capacity than the general elderly population. Moreover, the exclusion of individuals with comorbidities or cognitive and mobility impairments limits the applicability of these results to geriatric populations with more various clinical conditions. Including a broader range of participants beyond healthy individuals would enhance the external validity of these results for elderly populations with varying health conditions. Secondly, the factors measured for analysis may not encompass all variables that explain the variability in walking distance. Cognitive impairment, which was not assessed in this study, could also influence gait performance and test outcomes [38]. Indeed, nursing homes residents may also present more frequent cognitive impairments than community dwellers, which may affect the generalizability of our findings. To confirm the findings of this study, future research should consider additional factors, such as cardio-respiratory parameters and cognitive impairment, which could explain the walking performance reported in this study. Therefore, caution is warranted when interpreting or generalizing these results, particularly for frail or functionally impaired older adults. Finally, this study did not investigate potential physiological benefits associated with longer exercise duration, such as the activation of anti-aging pathways like Sirtuin 1, which may represent an additional advantage of the 6MWT and should be explored in future research [39].

In conclusion, this study provides evidence supporting the use of the 2MWT as a simpler and equivalent alternative to the 6MWT for assessing walking performance in elderly individuals, both in the community and in nursing homes. The study found that the 2MWT demonstrated high test-retest reliability, was equivalent to the 6MWT in measuring age-related differences in walking performance and was correlated with physical activity. Additionally, it highlighted the clinical utility of the 2MWT in assessing walking deterioration among elderly individuals, demonstrating performance as excellent as that of the 6MWT. Its shorter duration and comparable reliability make it a valuable tool for clinicians and researchers, particularly in settings with limited time and resources. The 2MWT effectively identifies older adults at risk of walking decline and suggests timely interventions to prevent further deterioration.

Declarations

Funding

The study was supported by Project ARES PFS (grant number: 2024 – MAA – 072).

Acknowledgement

The other members of the project are as follows: Veronique Feipel (Faculty of Motricity Sciences, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium), Patrick Willems (Faculty of Motricity Sciences, Université Catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium).

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Erasme Hospital (Date August 24, 2021/No. B4062021000237).

Author contribution statement

Duy Thanh Nguyen: Methodology, Writing – Reviewing & Editing, Data Curation, Formal Analysis.

Massimo Penta: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Review & Editing.

Nguyen Van Chinh: Funding Acquisition, Supervision, Review & Editing.

Chloé Sauvage: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Funding Acquisition, Supervision, Review & Editing.

References

2. Marcell TJ. Sarcopenia: causes, consequences, and preventions. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003 Oct;58(10):M911-6.

3. Tak E, Kuiper R, Chorus A, Hopman-Rock M. Prevention of onset and progression of basic ADL disability by physical activity in community dwelling older adults: a meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2013 Jan;12(1):329-38.

4. Torres-de Araújo JR, Tomaz-de Lima RR, Ferreira-Bendassolli IM, Costa-de Lima K. Functional, nutritional and social factors associated with mobility limitations in the elderly: a systematic review. Salud Publica Mex. 2018 Sep-Oct;60(5):579-85.

5. Shinkai S, Watanabe S, Kumagai S, Fujiwara Y, Amano H, Yoshida H, et al. Walking speed as a good predictor for the onset of functional dependence in a Japanese rural community population. Age Ageing. 2000 Sep;29(5):441-6.

6. Dehi M, Aghajari P, Shahshahani M, Takfallah L, Jahangiri L. The effect of stationary walking on the quality of life of the elderly women: a randomized controlled trial. J Caring Sci. 2014 Jun 1;3(2):103-11.

7. Clague-Baker N, Robinson T, Hagenberg A, Drewry S, Gillies C, Singh S. The validity and reliability of the Incremental Shuttle Walk Test and Six-minute Walk Test compared to an Incremental Cycle Test for people who have had a mild-to-moderate stroke. Physiotherapy. 2019 Jun;105(2):275-82.

8. Kervio G, Carre F, Ville NS. Reliability and intensity of the six-minute walk test in healthy elderly subjects. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003 Jan;35(1):169-74.

9. Guerra-Balic M, Oviedo GR, Javierre C, Fortuño J, Barnet-López S, Niño O, et al. Reliability and validity of the 6-min walk test in adults and seniors with intellectual disabilities. Res Dev Disabil. 2015 Dec;47:144-53.

10. Enright PL, McBurnie MA, Bittner V, Tracy RP, McNamara R, Arnold A, et al. The 6-min walk test: a quick measure of functional status in elderly adults. Chest. 2003 Feb;123(2):387-98.

11. Rikli RE, Jones CJ. The reliability and validity of a 6-minute walk test as a measure of physical endurance in older adults. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 1998 Oct 1;6(4):363-75.

12. Langhammer B, Stanghelle JK. The Senior Fitness Test. J Physiother. 2015 Jul;61(3):163.

13. Connelly DM, Thomas BK, Cliffe SJ, Perry WM, Smith RE. Clinical utility of the 2-minute walk test for older adults living in long-term care. Physiother Can. 2009 Spring;61(2):78-87.

14. Butland RJ, Pang J, Gross ER, Woodcock AA, Geddes DM. Two-, six-, and 12-minute walking tests in respiratory disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982 May 29;284(6329):1607-8.

15. Sikandar MA, John V. A study to investigate test-retest reliability of two minute walk test to assess functional capacity in elderly population. Indian J Physiother Occup Ther. 2015 Jul;9:108-13.

16. Benavent-Caballer V, Lisón JF, Rosado-Calatayud P, Amer-Cuenca JJ, Segura-Orti E. Factors associated with the 6-minute walk test in nursing home residents and community-dwelling older adults. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015 Nov;27(11):3571-8.

17. Cote CG, Casanova C, Marín JM, Lopez MV, Pinto-Plata V, de Oca MM, et al. Validation and comparison of reference equations for the 6-min walk distance test. Eur Respir J. 2008 Mar;31(3):571-8.

18. Bittner V, Weiner DH, Yusuf S, Rogers WJ, McIntyre KM, Bangdiwala SI, et al. Prediction of mortality and morbidity with a 6-minute walk test in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. SOLVD Investigators. JAMA. 1993 Oct 13;270(14):1702-7.

19. Kubo H, Nozoe M, Kanai M, Furuichi A, Onishi A, Kajimoto K, et al. Reference value of 6-minute walk distance in patients with sub-acute stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2020 Jul;27(5):337-43.

20. ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002 Jul 1;166(1):111-7.

21. Bohannon RW, Wang YC, Gershon RC. Two-minute walk test performance by adults 18 to 85 years: normative values, reliability, and responsiveness. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015 Mar;96(3):472-7.

22. Mandrekar JN. Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. J Thorac Oncol. 2010 Sep;5(9):1315-6.

23. Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of clinical research: applications to practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall; 2009.

24. Chan WLS, Pin TW. Reliability, validity and minimal detectable change of 2-minute walk test, 6-minute walk test and 10-meter walk test in frail older adults with dementia. Exp Gerontol. 2019 Jan;115:9-18.

25. Wu G, Sanderson B, Bittner V. The 6-minute walk test: how important is the learning effect? Am Heart J. 2003 Jul;146(1):129-33.

26. Spencer L, Zafiropoulos B, Denniss W, Fowler D, Alison J, Celermajer D. Is there a learning effect when the 6-minute walk test is repeated in people with suspected pulmonary hypertension? Chron Respir Dis. 2018 Nov;15(4):339-46.

27. Uszko-Lencer NHMK, Mesquita R, Janssen E, Werter C, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Pitta F, et al. Reliability, construct validity and determinants of 6-minute walk test performance in patients with chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2017 Aug 1;240:285-290.

28. Roush J, Heick JD, Hawk T, Eurek D, Wallis A, Kiflu D. Agreement in walking speed measured using four different outcome measures: 6-meter walk test, 10-meter walk test, 2-minute walk test, and 6-minute walk test. Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice. 2021;19(2):7.

29. Hansen A, Nim CG, O'Sullivan K, O'Neill S. Testing walking performance in patients with low back pain: will two minutes do instead of six minutes? Disabil Rehabil. 2024 Mar;46(6):1173-7.

30. Mathias S, Nayak US, Isaacs B. Balance in elderly patients: the "get-up and go" test. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1986 Jun;67(6):387-9.

31. Bohannon RW. Sit-to-stand test for measuring performance of lower extremity muscles. Percept Mot Skills. 1995 Feb;80(1):163-6.

32. Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995 Mar 2;332(9):556-61.

33. Bautmans I, Lambert M, Mets T. The six-minute walk test in community dwelling elderly: influence of health status. BMC Geriatr. 2004 Jul 23;4:6.

34. Steffen TM, Hacker TA, Mollinger L. Age- and gender-related test performance in community-dwelling elderly people: Six-Minute Walk Test, Berg Balance Scale, Timed Up & Go Test, and gait speeds. Phys Ther. 2002 Feb;82(2):128-37.

35. Casanova C, Celli BR, Barria P, Casas A, Cote C, de Torres JP, et al. The 6-min walk distance in healthy subjects: reference standards from seven countries. Eur Respir J. 2011 Jan;37(1):150-6.

36. Nguyen DT, Penta M, Questienne C, Garbusinski J, Nguyen CV, Sauvage C. Normative values in healthy adults for the 6-minute and 2-minute walk tests in Belgium and Vietnam: implications for clinical practice. J Rehabil Med. 2024 Mar 19;56:jrm18628.

37. Camarri B, Eastwood PR, Cecins NM, Thompson PJ, Jenkins S. Six minute walk distance in healthy subjects aged 55-75 years. Respir Med. 2006 Apr;100(4):658-65.

38. Ries JD, Echternach JL, Nof L, Gagnon Blodgett M. Test-retest reliability and minimal detectable change scores for the timed "up & go" test, the six-minute walk test, and gait speed in people with Alzheimer disease. Phys Ther. 2009 Jun;89(6):569-79.

39. Martins IJ. Anti-aging genes improve appetite regulation and reverse cell senescence and apoptosis in global populations. Advances in Aging Research. 2016 Jan;5(1):9-26.