Abstract

Background: Evaluation of the effects of chemicals on the liver in vivo, is an essential part of drug development. Here, it is hypothesized that a clinical index of liver fibrosis i.e. FIB-4 could be used as a simple, objective tool in preclinical in vivo studies for detection of hepato-active chemicals. The aim is to determine the sensitivity, specificity, and applicability of FIB-4 index in preclinical hepatic studies.

Method: Online research databases were searched to identify published safety pharmacological/toxicological studies with tabulated hepatograms and hematograms from 2008-2019. The relationship between the parameters used in computing Liver Fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4) were analyzed by linear regression. The sensitivity and specificity of FIB-4 index in preclinical hepatic studies were estimated using Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC).

Results: Twenty five (25) published preclinical safety pharmacological/toxicological studies were selected. In the preclinical studies, the relationship between FIB-4 index and its independent variables was linear. This relationship was independent of the hepatotoxicant, or the experimental animal used. Using the Run’s test, none of the studies deviated from linearity. For sensitivity and specificity, Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) was 0.9698 ± 0.008989 (95% Cl 0.9522 to 0.9874 at p < 0.0001 ****). The separability or discriminatory performance between hepatotoxic and hepatoprotective substances was 0.5959 ± 0.03899 (95% Cl 0.5194 to 0.6723 p=0.01542). FIB-4 index of the naïve/sham/ vehicle control treated animals was less than that of the hepatotoxicant treated animals. Hepatoprotective chemicals exhibit FIB-4 index approximately to or less than that of the naive/vehicle /sham treated animals. The ratio of FIB-4 index of toxicant treated to FIB-4 of the naïve/sham/ vehicle control treated animals was greater than 1. Hepatotoxicity also correlated with decreased platelet count.

Conclusion: FIB-4 index is a simple, sensitive, objective tool that can be used in preclinical hepatic toxicological/ safety pharmacology studies as an auxiliary and complimentary tool to aid in detection of hepatoactive substances.

Keywords

Hepatotoxicity, Hepatoprotective, Animal models, Liver damage, Carbon tetrachloride, Paracetamol

Introduction

The liver plays a pivotal role in intermediary metabolism, biosynthesis, and pharmacotherapy. As such, chemical influences can result in detrimental effects. Anatomically, the liver is centrally placed, with loose capillary fenestrations, which makes it susceptible to chemical assault [1]. Epidemiological evidence shows that chemical-induced liver injury is a major cause of acute liver failure, fibrosis and cirrhosis [2,3]. In preclinical studies, drug-induced liver injury is a major reason why many interesting lead molecules and novel compounds fail to transcend beyond the laboratory. It is also the principal reason for withdrawal of market authorization of medicines [4]. Furthermore, with ever increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus, obesity, and alcohol consumption, the burden of liver diseases is expected to increase [5]. Individuals with compromised liver may require dose adjustments or complete avoidance of some essential medicines which otherwise may have been appropriate to their medical condition

New chemicals products, synthetic or natural, are continually being screened to discover cures. Amidst the ethical concerns, in vivo models provide the most predictable outcome to the expected human experiences [6]. This places an extra responsibility on the researcher to develop ethically acceptable models that perfectly simulate the pathobiology of human disease. In experimental hepatic safety pharmacology, the Gold standard test is a costly procedure of examining the effects of new drugs on liver histoarchitecture, biosynthetic function as well as on effects on endoboitic and xenobiotic biotransforming enzymes. For credibility of findings, researchers produce photomicrographs for histopathological analysis [7]. Despite major advances in chemical detection and tissue staining techniques, haematoxyllin and eosin staining are widely employed especially in resource constrained settings [8]. As it has been reported in human liver fibrosis, accuracy in results inference is affected by sampling errors and variability in pathological interpretation [9]. In dissemination of results, researchers present photomicrographs which in their subjective opinion best represent their findings. The possibility of making a type 1 error in these instances could be underestimated.

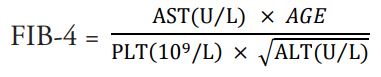

Clinically, to address limitations with liver biopsies, many simple, direct or indirect, objective, non-invasive indexes were developed to estimate and diagnose liver damage [10-13]. However, these indexes are yet to be fully assimilated in preclinical hepatic toxicological studies. In hepatic fibrosis in human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus infections, Sterling et al., proposed that the ratio of magnitude of the product of age and aspartate transaminase levels to the product of platelet count and square root of alanine transaminase levels of a patient is indicative of stage of liver fibrosis [14]. Sterling et al., (2006) had argued that age, AST, ALT, and platelet are simple indicators of liver fibrosis.

A number of well controlled studies and scientific reviews have assessed and recommended the diagnostic performance of the FIB-4 index [15-18]. Since the FIB-4 index parameters are routinely measured in preclinical settings, we hypothesized that FIB-4 index could be a simple tool for preclinical hepatic toxicological studies. The advantage will be to reduce cost, reduce number of animals needed for experimentation, and provide a means of easily screening large number of chemicals for hepatic effects whilst minimizing sampling errors and variability in results interpretation of results.

Methodology

Search strategy

The study relied on secondary data from published preclinical hepatic toxicological/safety pharmacological studies. Research databases including Google Scholar, Pubmed, Medline, Web of Science, and Researchgate were purposively searched to obtain in vivo preclinical data between the years of 2008 and 2019. Word combinations such as hepatoprotective, hepatotoxicity, hematology, rats, mice, rabbits, paracetamol, carbon tetrachloride, isoniazid, liver damage were used as search items to retrieve relevant publications. Abstracts and full texts were screened, and a decision made on each paper based on a predefined criteria. In addition, reference lists as well as citations of selected studies were searched to obtain other relevant papers. This was done until there was a clear saturation in search.

Types of study designs included

The initial search results were analyzed according to a predefined criteria:

- That the study should include a hematogram/leaucogram where thrombocyte count has been reported as mean ± SEM in tabular form not graphical.

- The study should include a hepatogram with liver enzymes, alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) reported as mean ± SEM in tabular form not graphical.

Types of studies excluded

- Preclinical and experimental toxicological/safety pharmacological studies with tabular presentations of hematograms or hepatograms were used. Studies that presented results graphically were not included because graphs may not have attached scales to help estimate the actual mean ± SEM.

- Preclinical toxicological/pharmacological studies which fell outside the study period of 2008 to 2019.

Treatment of data

The experimental design of each of the selected studies including doses, mean platelet counts, AST and ALT were extracted and transferred to Microsoft excel 2013 data sheet. All statistical analysis was done using Graph pad prism version 6. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to estimate linear relationship between quantities. To determine the diagnostic value of FIB-4 in preclinical research, an evaluation was performed to determine the sensitivity and specificity based on Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) using APRI tool (AST to Platelet Ratio Index) computed from the studies as standard.

Testing for Linearity: Linear regression was used to analyze each of the selected studies. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used as a test for correlation. Runs test (Wald–Wolfowitz) was used to test for departure from linearity.

Theory

Applying the equation y=mx + c, plot of mean platelet count against AST/√ALT will give AGE/FIB-4 as slope when the intercept c = 0

Estimating FIB-4 index for each dose level of the selected studies: Using the equation

Estimating the interaction between the parameters: The relationship between platelet counts, AST and ALT was estimated using linear regression.

Assumptions

- The quantitative data and mean, was used to represent each dose level. To simplify calculation, the dispersion from the mean i.e. standard error of the mean was ignored.

- In order to use the formula, the age of all animals in the experimental design was made constant (k=1). This was because secondary data doesn’t include the age of animals in a group. Secondly, experimental induction of liver damage is rapid and occurs within a defined time period contrary to clinical liver damage which may be gradual and over a long period. This suggests that age may not be an important factor in a well-controlled and matched study.

- To test the sensitivity and specificity of FIB-4, we had to compare the FIB-4 value to the conclusions reached by the primary researchers at each dose level in the 25 studies. The individual dose levels were 148. To objectively accomplish this, the APRI tool was used to compute a value for each dose level, and this was subsequently matched with its corresponding FIB-4 value at the dose level.

Results

Characteristics of selected studies

Twenty five (25) published preclinical studies with hematograms and hepatograms met the inclusion criteria. Eighty Four percent of the study (n= 21) used either Sprague – dawley or Wister rats. Twelve percent used rabbits as experimental animals and four percent used mice. Hepatotoxicity was induced with carbon tetrachloride, paracetamol, potassium dichromate, hydroxyapatite, isoniazid, methyl methanesulfonate, sodium fluoride or hepatotoxicant combinations such isoniazid plus rifampicin, cadmium plus paracetamol, mercury plus paracetamol, lead plus paracetamol (Table 1).

Linear analysis

In subjecting each experiment to linear regression analysis by plotting platelet count (dependent variable) against AST/√ALT (independent variable) a linear association was noted. To confirm whether or not the data had correlation with these parameters, Run’s test of randomness was employed. There was no significant deviation from linearity by the Run test for randomness for all the 25 studies (Table 1).

Estimating FIB-4 index

The FIB- 4 index

Using the formula FIB-4= and assuming that the age of every animal in the study was constant i.e. 1, the FIB- 4 index was estimated for every dose level. There were 148 indexes obtained from the 25 studies. In 80% of the cases, the FIB-4 index of the toxicant control group was higher than FIB-4 index of naïve or unexposed group. As such, the ratio of the toxicant control FIB-4 to the naïve/vehicle FIB-4 was greater than 1 (Table 1).

In Eighty-five percent of studies (17 out of 20) FIB-4 index of hepatoprotective groups was similar to or less than that of untreated controls and different from the toxicant control. In all these instances the conclusion drawn from this study was in line with that of the primary authors/ researchers. For approximately twelve percent of the studies, the ratio of the FIB-4 toxicant to control was approximately equal to 1 i.e (0.8- 0.99). In 8 percent of studies (2/25) ratio of FIB-4 was below 0.5. (Table 1).

Consistently, the FIB-4 index was able to detect diverse hepatoactive chemicals presupposing that FIB-4 index was less chemical nature specific but rather more dose and duration dependent.

Relation between FIB-4 ratios and Pearson’s correlation coefficient

There was an association between the direction of the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) estimated from the linear regression and the strength and the size of the calculated ratio of FIB-4 (toxicant) to FIB-4 vehicle control. Consequently, a strong negative Pearson’s correlation coefficient correlated with a high calculated ratio. For the 20% of the study of which the estimated FIB-4 deviated from the expected, the Pearson’s correlation Coefficient (r) was weakly negative or positive (Table 1).

|

Hepatology Study |

Experimental Design |

FIB-4 Index |

FIB -4 Toxic Control/ FIB-4 of Vehicle Control |

Linear Equation & Pearson Coeffficient |

|

Senthilkumar et al., [39] |

Control |

0.00031 |

2.97 |

Y = 0.01939*X - 0.0 r =-0.8479; R2 = 0.7189 |

|

APAP |

0.00092 |

|||

|

SIL 25 mg |

0.00031 |

|

||

|

Rh 200 mg |

0.00024 |

|

||

|

Rh 400 mg |

0.00025 |

|

||

|

Ujah et al., [40] |

control |

0.0004 |

0.325 |

Y = 0.02665*X - 0.0 r= 0.8566 R2 = 0.7338 |

|

CCL4 |

0.00013 |

|||

|

CCL4 + CO 500 |

0.0002 |

|

||

|

CCL4 + CO 750 |

0.00018 |

|

||

|

CCL4 + CO 1 mg |

0.00016 |

|

||

|

Dwivedi et al., [41] |

control |

0.000066 |

1.15 |

Y = 0.01101*X - 0.0 r= -0.9005 R2 =0.8108 |

|

APAP 900 mg |

0.000076 |

|||

|

APAP+ Liv |

0.000066 |

|

||

|

Bera et al., [42] |

control |

0.00031 |

1.42 |

Y = 0.01241*X - 0.0 r= -0.9874** R2 =0.9749 |

|

Liv |

0.00044 |

|||

|

CCL4 |

0.00031 |

|

||

|

CCL4 + LIvshis |

0.00031 |

|

||

|

CCL4 + Silymarin |

0.00032 |

|

||

|

Nwidu et al., [43] |

control |

0.042455 |

1.14 |

Y = 0.02081*X - 0.0 r= 0.05034 R2 = 0.002534 |

|

CCL4 |

0.048286 |

|||

|

CCL4+SML 500 |

0.01632 |

|

||

|

CCL4+SML 1000 |

0.009729 |

|

||

|

CCL4+SMS500 |

0.023959 |

|

||

|

CCL4+SMS 1000 |

0.016749 |

|

||

|

CCL4+ sl |

0.003972 |

|

||

|

Iroanya et al., [44] |

Control |

0.057 |

13.16 |

Y = 0.007329*X - 0.0 r=-0.9902 **** R2 = 0.9805 |

|

APAP 3g |

0.75 |

|||

|

APAP +E +2g |

0.0867 |

|

||

|

APAP +E +4g |

0.0594 |

|

||

|

APAP +E8g |

0.071 |

|

||

|

APAP + Liv 52 |

0.069 |

|

||

|

APAP + Sil |

0.0541 |

|

||

|

Tzankova, et al., [45] |

Control |

0.019 |

0.48 |

Y = 0.01188*X - 0.0 r=-0.2346 R2 = 0.05504

|

|

APAP 100 |

0.0092 |

|||

|

QR+ APAP QR-NP1 +PC |

0.0105 0.0121 |

|

||

|

QR-NP2+ PC |

0.0171 |

|

||

|

El-Megharbel et al., [46] |

Control |

0.0051 |

4.49 |

Y = 0.02160*X - 0.0 r =-0.9818 ** R2 = 0.9638

|

|

APAP |

0.0229 |

|||

|

Cd2+/APAP |

0.017 |

3.333 |

||

|

Hg2+/APAP |

0.0545 |

10.68 |

||

|

Pb2+/APAP |

0.0623 |

12.22 |

||

|

Payasi et al., [47] |

Control (M) |

0.0249 |

|

Y = 0.02036*X - 0.0 r = -0.8093* R2 = 0.6550 |

|

APAP 16.6 mg |

0.0224 |

0.90 |

||

|

APAP 33.6 |

0.0229 |

0.91 |

||

|

Para 66.6 |

0.0201 |

0.81 |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Control (f) |

0.0236 |

|

||

|

Para 16.6 |

0.0238 |

0.99 |

||

|

Para 33.6 |

0.0226 |

1.04 |

||

|

Para 66.6 |

0.0219 |

1.077 |

||

|

Shanmugam et al., [48] |

control |

0.01779 |

0.988 |

Y = 0.01765*X - 0.0 r = 0.4242 R2 = 0.1800

|

|

Para 2g/kg |

0.01758 |

|||

|

P + Sil 25mg/kg |

0.01688 |

|

||

|

P + P.s 200 mg/kg |

0.02239 |

|

||

|

P + P.s 400 mg/kg |

0.01656 |

|

||

|

Johnson et al., [49] |

control |

3.55 |

2.09 |

Y = 0.01532*X - 0.0 r = 0.8414 R2 = 0.7079* |

|

APAP |

7.422 |

|||

|

SIL 100 mg/kg |

4.025 |

|

||

|

Vit C 100 mg/k |

5.41 |

|

||

|

VA 300 mg/kg |

4.56 |

|

||

|

AZ 300 mg/kg |

4.95 |

|

||

|

Rao et al., [50] |

Control |

1.789 |

1.689 |

Y = 0.02028*X - 0.0 r = -0.04710 R2 = 0.002219

|

|

APAP |

3.0227 |

|||

|

APAP + CE C.t |

2.486 |

|

||

|

APAP + PE C.t |

2.61 |

|

||

|

APAP + Sil |

1.727 |

|

||

|

Rashid et al., [51] |

Control |

0.0088 |

1.136 |

Y = 0.009916*X - 0.0 r = 0.3075 R2 = 0.09456 |

|

AMP 750 |

0.01 |

|||

|

AMP + Sily 50 |

0.012 |

|

||

|

AMP + FOM 200 |

0.011 |

|

||

|

AMP + FOM 400 |

0.0079 |

|

||

|

FOM 400 |

0.00953 |

|

||

|

Aziz et al., [52] |

Control |

0.055 |

1.69 |

Y = 0.06666*X - 0.0 r = -0.8982 R2= 0.8067

|

|

GMC |

0.093 |

|||

|

GMC+SMN |

0.0597 |

|

||

|

GMC+LQA |

0.0669 |

|

||

|

GMC+HQA |

0.068 |

|

||

|

Aroonvilairat et al., [53] |

Control |

0.013 |

|

Y = 0.01224*X - 0.0 r = -0.3287 R2= 0.1080

|

|

Low |

0.0138 |

1.06 |

||

|

Medium |

0.01256 |

0.96 |

||

|

High |

0.0106 |

0.81 |

||

|

Nwidu & Teme [54] |

control |

0.2446 |

0.529 |

Y = 0.01530*X - 0.0 r = 0.3882 R2= 0.1507 |

|

RIF+INF |

0.1295 |

|||

|

HALA+RIF+INH |

0.1838 |

|

||

|

H 500+RIF+INH |

0.1285 |

|

||

|

H 1000+RIF+INH |

0.1867 |

|

||

|

SIL |

0.149 |

|

||

|

Nwidu et al., [55] |

control |

0.08049 |

1.01 |

Y = 0.05879*X - 0.0 r = -0.4554 R2= 0.2074 |

|

RIF+INH |

0.08169 |

|||

|

RIF+INH+TO 100 |

0.0579 |

|

||

|

RIF+INH+TO 125 |

0.05919 |

|

||

|

RIF+INF+TO500 |

0.05085 |

|

||

|

RIF+INF+T+ S 50 |

0.05777 |

|

||

|

TOPE 250 |

0.04582 |

|

||

|

Atmaca et al., [56] |

Control |

0.03915 |

1.23 |

Y = 0.03081*X - 0.0 r = 0.5321 R2= 0.2832 |

|

Fluoride |

0.0481 |

|||

|

Resveratrol |

0.02459 |

|

||

|

F + resveratrol |

0.02786 |

|

||

|

Ismail et al., [57] |

control |

0.01274 |

0.93 |

Y = 0.01075*X - 0.0 r = 0.3442 R2= 0.1185 |

|

NaF |

0.01179 |

|||

|

quercetin |

0.01189 |

|

||

|

Black berry |

0.01277 |

|

||

|

Black berry+ NaF |

0.00836 |

|

||

|

quercetin+NaF |

0.00831 |

|

||

|

NaF+quercetin+Bl |

0.00948 |

|

||

|

Bouasla et al., [58] |

control |

0.01664 |

1.59 |

Y = 0.01699*X - 0.0 r = -0.6657 R2= 0.4432 |

|

NaF |

0.02639 |

|||

|

NaF +PGF |

0.01249 |

|

||

|

PGF |

0.01492 |

|

||

|

Chen et al., [59] |

control |

0.0348 |

1.19 |

Y = 0.03298*X - 0.0 N/A |

|

HA NPs |

0.0415 |

|||

|

Abdel-Ghaffar et al., [60] |

control |

0.012 |

2.12 |

Y = 0.01662*X - 0.0 r = -0.3146 R2= 0.09899 |

|

INH- |

0.0254 |

|||

|

NGN+INH |

0.0135 |

|

||

|

NGN |

0.01452 |

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

control |

0.0117 |

1.85 |

||

|

INH- |

0.0217 |

|||

|

NGN+INH |

0.0115 |

|

||

|

NGN |

0.0133 |

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

control |

0.0155 |

1.709 |

||

|

INH- |

0.0265 |

|||

|

NGN+INH |

0.01405 |

|

||

|

NGN |

0.0147 |

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

control |

0.01396 |

2.42 |

||

|

INH- |

0.03381 |

|||

|

NGN+INH |

0.01234 |

|

||

|

NGN |

0.01613 |

|

||

|

Hussain et al., [61] |

Control |

0.028218 |

1.81 |

Y = 0.03596*X - 0.0 r= -0.8475 R2= 0.7183 |

|

INH 100 mg/kg |

0.051255 |

|||

|

INH+ sil 100 |

0.02936 |

|

||

|

INH+ phd300 mg/kg |

0.03978 |

|

||

|

INH+phd300 mg/kg |

0.035581 |

|

||

|

Momo et al., [62] |

Control |

0.027 |

|

Y = 0.03450*X - 0.0 r= -0.4585 R2= 0.2102

|

|

K2CR2O7 10 mg/kg |

0.052 |

1.925 |

||

|

K2CR2O7 20 mg/kg |

0.0369 |

1.36 |

||

|

K2CR2O7 30 mg/kg |

0.0363 |

1.34 |

||

|

Oshida et al., [63] |

control 4H |

0.146 |

|

Y = 0.2217*X - 0.0 r= -0.1076 R2 = 0.01158

|

|

MMS 50 mg/kg |

0.22 |

1.50 |

||

|

MMS 100 mg/kg |

0.227 |

1.55 |

||

|

MMS 150 mg/kg |

0.401 |

2.74 |

||

|

AFTER TOXICANT WITHDRAWAL |

||||

|

control |

0.28 |

|

||

|

MMS 50 mg/kg |

0.166 |

0.59 |

||

|

MMS 100 mg/kg |

0.24477 |

0.87 |

|

|

|

MMS 150 mg/kg |

0.156 |

0.56 |

||

Sensitivity and specificity of FIB-4

To test the sensitivity and specificity of the FIB-4 index as a tool in preclinical toxicology, the APRI index was computed with the APRI tool for each dose level of the selected studies (n=148). This was then used as standard for determining the sensitivity of FIB-4 index in preclinical studies.

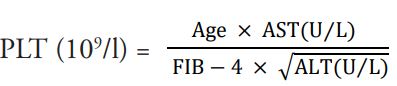

The Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristics Curve (AUC – ROC/ AUROC) was 0.9698 ± 0.008989 (95% Cl 0.9522 to 0.9874 at p < 0.0001 ****). This translates to about 95-98% sensitivity and specificity as a diagnostic model (Figure 1a).

Using Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristics Curve (AUC – ROC/ AUROC), the separability or discriminatory performance of FIB-4 index in predicting or separating hepatoprotective from hepatotoxic chemicals was between 51-67% (AUC – ROC/ AUROC 0.5959 ± 0.03899; 95% Cl 0.5194 to 0.6723; p= 0.01542) (Figure 1b).

Figure 1. Sensitivity and Specificity of the FIB-4 index as a tool in preclinical hepatic toxicological studies. A. APRI index was used as the standard for testing the sensitivity and specificity of FIB-4. The Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristics Curve (AUC – ROC/ AUROC) was 0.9698 ± 0.008989 (95% Cl 0.9522 to 0.9874 at p < 0.0001 ****). B. The separability or discriminatory performance of FIB-4 for hepato-active substances in 26 hepatic toxicology studies. The Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristics Curve 0.5959± 0.03899, 95% Cl 0.5194 to 0.6723 p= 0.01542.

Estimating the interaction between the parameters AST, ALT, Platelet

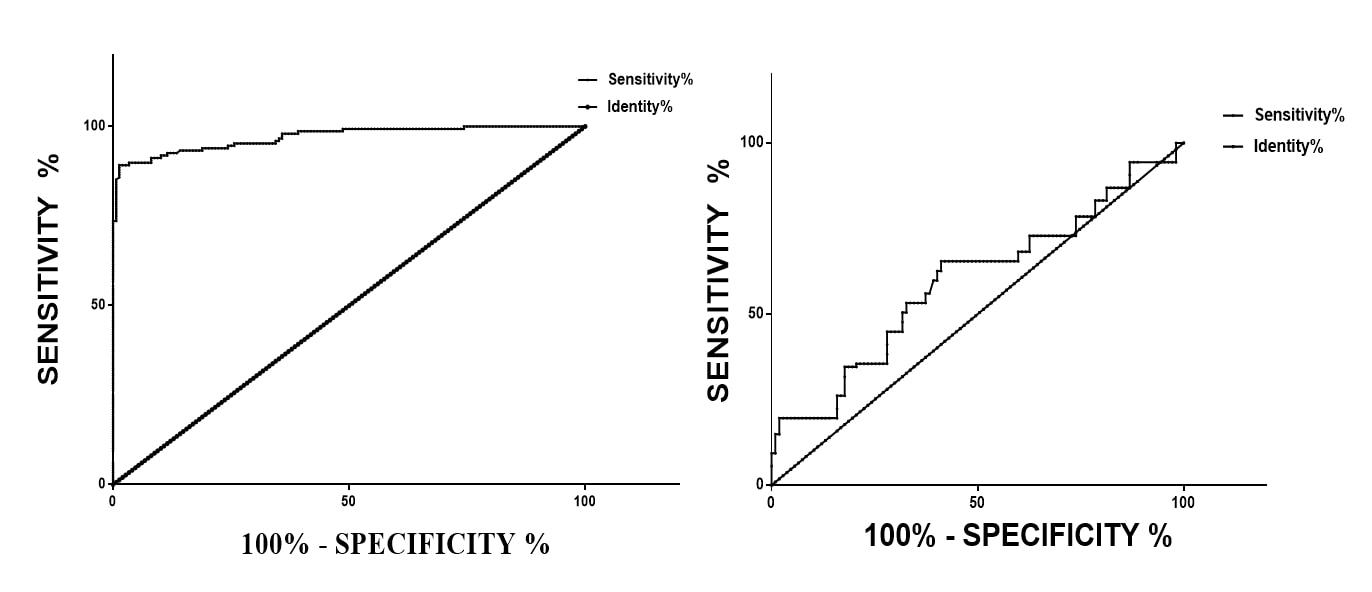

Liver enzymes: There was a positive linear autocorrelation between AST and √ALT. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was 0.5657. The Runs test for randomness was not statistically significant (0.2923). This indicates that in in vivo preclinical hepatic toxicology, an increase in ALT is associated with an increase AST (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The relation between mean √ALT (independent variable) and mean AST (dependent variable) extracted from 25 hepatic toxicological studies (n=148) using murine and lagomorph models. The p value using Run’s test was 0.2923.

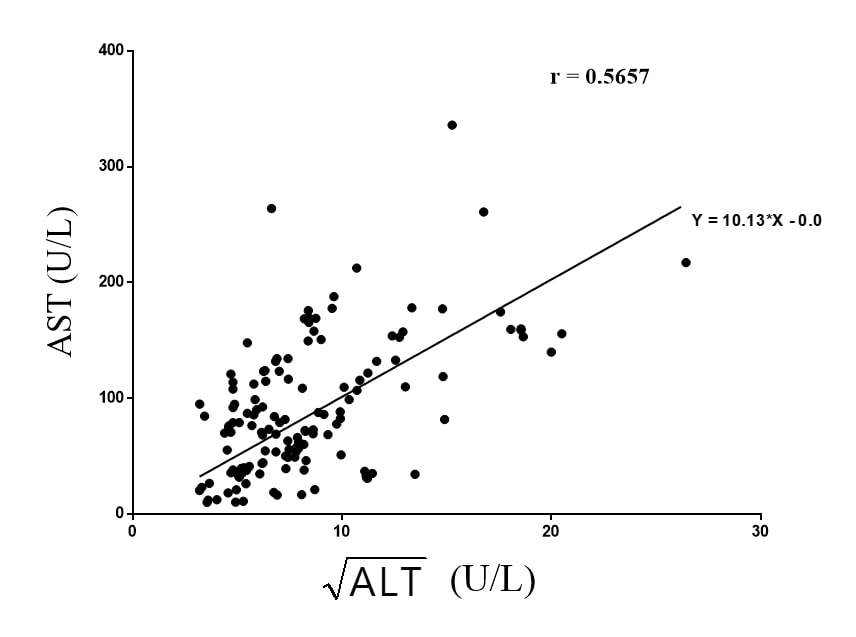

Thrombocytes: In all the 25 selected studies, platelet count was an indicator of hepatic activity. Hepatotoxicity and liver damage consistently resulted in decreased platelet count. Treatment with hepatoprotective agents such as silamyrin reversed the decrease. The decrease in platelet count was independent on the kind of hepatotoxic agent used. This was confirmed as Area Under the Curve of the vehicle control (AUC 18840; mean 461.7 ± 36.03) was higher than that of the of toxicant control (AUC = 15931; mean 438.9 ± 52.99). The D'Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test indicated that the platelet counts of vehicle control were normally distributed whereas that of the hepatotoxic groups was skewed (K2 of 2.741 vs 49.93 < 0.0001) (Figures 3a & 3b).

Figure 3. The figure represents mean platelets counts (n=43) extracted from 25 in vivo hepatotic toxicological studies in murine and lagomorphs. A. The AUC for Naïve (vehicle) controls and Toxicant controls were 18840 vrs 15931, mean±SEM were 461.7±36.03 vrs 438.9±52.99 and the K2 values were 2.741±49.93**** respectively. B. Mean Platelet count from Naïve controls and Hepatotoxic controls. p values was 0.2707 t-test.

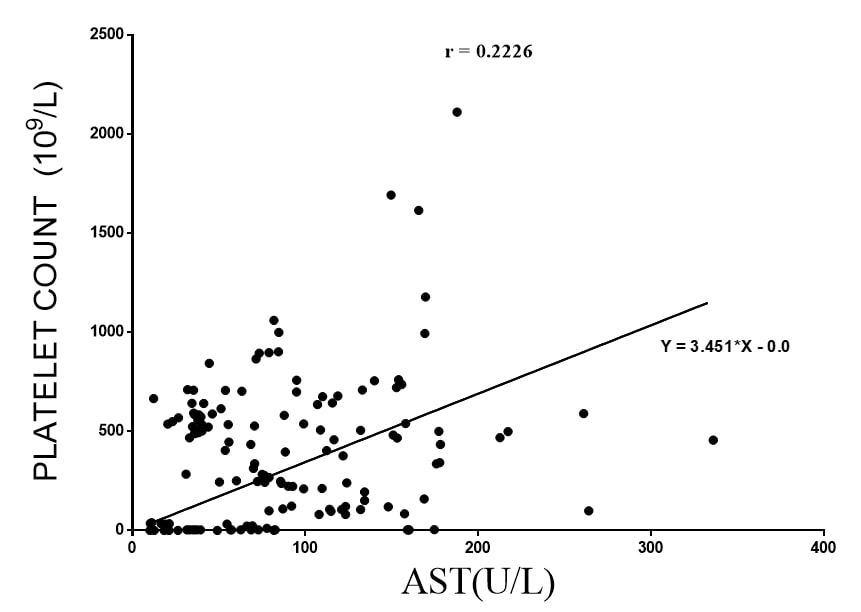

Platelet and Liver enzymes: In examining each of the results, it was apparent that an increase in the liver enzymes AST and ALT generally corresponded with a decrease in platelet count. There was a weak positive linear relationship between AST and platelet count. Using linear regression equation Y = 3.451*X - 0.0, the slope was 3.451 ± 0.2984, the Pearson’s coefficient (r) was 0.2226 at a p value of 0.0065 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The relation between mean AST (independent variable) and mean Platelet count (dependent variable) extracted from 25 hepatic toxicological studies (n=148) using murine and lagomorph models. The p value using Run’s test was 0.1093.

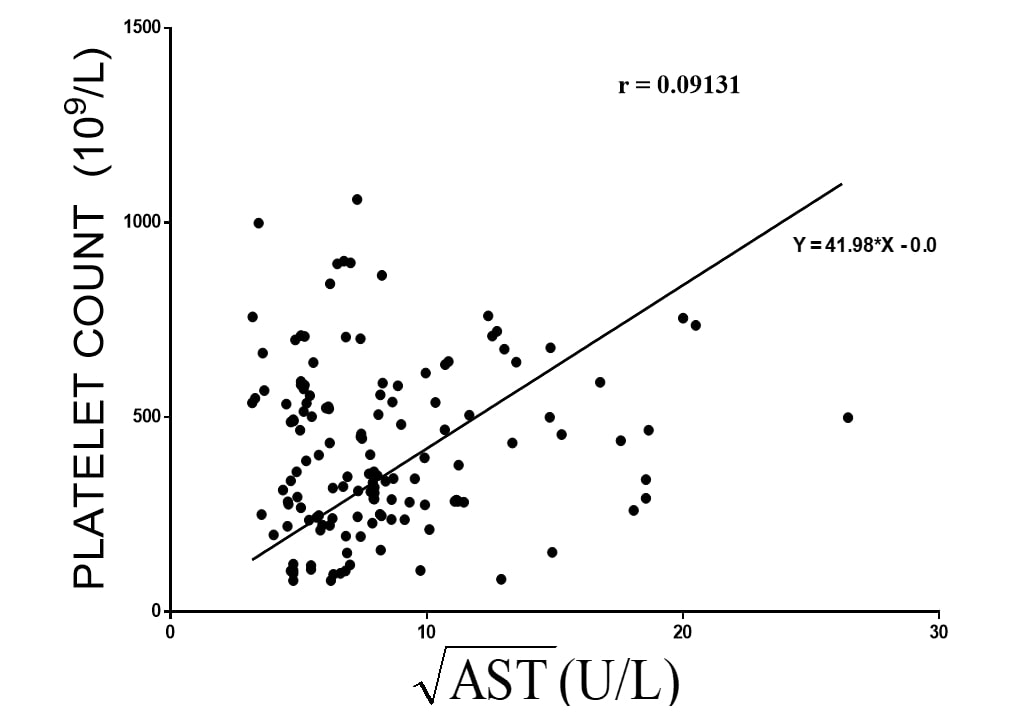

Platelet and √ALT: Similarly, using the equation Y = 41.98*X - 0.0, at a slope of 41.98 ± 2.474, there are a virtually little or no correlation between √ALT and platelet count. Furthermore, there was a significant degree of randomness within the data set using Run test. The Pearson coefficient (r) was 0.0913, the Runs test was 0.0021 (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The relation between mean square root of ALT √ALT (independent variable) and mean Platelet count (dependent variable) extracted from 25 hepatic toxicological studies (n=148) using murine and lagomorph models. The p value using Run’s test was significant at 0.0021.

Discussions

The liver’s susceptibility to chemical assault results from its blood perfusion rate, anatomical position, complex biochemical processes, and its role in chemical disposition [1]. A number of experimental models have been developed to determine the safety of medicinal products over the years. Preclinical safety studies are very laborious, expensive, and may require the use of large number of animals. A sensitive but less costly model can aid in the screening for many hepatoactive substances. Using a clinical index of liver fibrosis, we had proposed that hepatoactivity could easily be quantified from simple measure of platelet, AST and ALT levels experimentally.

During the literature search, it was apparent that many preclinical hepatic toxicological studies did not include hematograms. In some studies, haematological analysis omitted platelet count. However, there is strong scientific literature supporting the indispensable role of the liver in hematopoiesis [18]. In fact, in developmental biology, the liver is recognized as a haematopoietic organ and, more importantly, several elucidated hepatic processes involve interactions with blood derived cells or factors [19]. As such, hepatic damage invariably reflects as haematological aberrations. In line with this, many well-studied hepatotoxicants mechanistically interact with hematostaic factors [20-22].

Hepatic stellate cells appear to initiate and coordinate the actions of other mediators of liver damage [23]. Sinusoidal and sub-endothelial hepatic stellate cells induce sequestration of circulating thrombocytes during early phase of hepatic chemical injury. As such, thrombocytopenia is common to the pathophysiology of many hepatic disorders [24-26]. This has also been demonstrated in preclinical animal models of experimental liver fibrosis. Subsequently, liver damage has been managed experimentally with some degree of success using platelets or platelet rich fractions [27-29]. From this study, an important biomarker of hepatic damage is a decrease in platelet count. Again, liver regeneration was characterized by reversal of thrombocytopenia. This was evident in studies that employed silymarin or antioxidants. Ideally, the best time for therapeutic intervention in curative preclinical hepatic toxicological study should be after detection of appreciable decrease in platelet count.

The thrombotic pathway links up with the inflammatory cascade during hepatic injury and these two processes may be induced by reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress [30]. Tissue necrosis factor from macrophages/monocytes acting through TNF receptor 1 in the early phases of acute inflammation activate hepatic stellate cell which regulates matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) expression and extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition [30-32]. The damage to hepatocytes causes the release of liver enzymes.

The two hepatic enzymes used in computing FIB-4 index exhibit different kinetic profiles. ALT is exclusively cytosolic and has a half-life of 47 hours [34,35]. It is a widely accepted specific indicator of hepatic injury than AST in humans [34]. There are two isoforms of AST. The cytosolic isoenzyme which is released early upon damage to hepatocytes has a short half-life of 17.5 hours and the delayed release of mitochondria enzyme which has a half-life of approximately 87 hours [36]. In analyzing the relationship between platelet count and liver enzymes, there was a correlation, albeit weak, between a decrease in platelet count and an increase in AST levels during chemical assault. However, there was a very minimal correlation between the decrease in platelet count and the rise in alanine transaminase. From our analysis, APT may be more sensitive and auto correlate to changes in platelet count than alanine transaminase. Perhaps, this may be the basis for the use of APRI index as a tool for clinical diagnosis of fibrosis.

However, in most human hepatic disorders, except alcoholic hepatitis and Reye syndrome, ALT activity level is higher than that of AST and a very good indicator of hepatic injury [37]. Contrary to this, in examining preclinical hepatic studies, AST activity levels were higher than ALT in most of the studies. It is possible that most experimental hepatotoxicants mechanistically target the mitochondria or are used for prolong periods, causing mitochondrial damage.

The sensitivity and specificity of FIB-4 as a diagnostic tool in preclinical hepatic toxicology study based on AUROC was about 95-98%. According to Zhijian et al., a diagnostic tool with Area Under the Reciever Operator Curve greater than 90% is an excellent tool [38]. This clearly indicates that FIB-4 has the potential to be a good tool for detecting hepatoactive substances. We further analyzed to see if FIB-4 index could discriminate or separate hepatotoxic from hepatoprotective chemicals in these selected studies. It’s performance was averagely 60% (51-67). This finding was important because the data employed were not homogenous. Variations between laboratories, differences in study design, different animal species, nutrition status of animals especially pyridoxine levels, sensitivity of equipment could all influence the outcome. In fact, some of the studies, selected and included here, used dose regimen of hepatotoxicant that could not possibly have induced hepatic damage. Again, because we employed secondary data without dispersions from the mean; the discriminatory performance or separability of FIB-4 in the studies could have been affected.

Summary of findings and recommendations

- In preclinical studies, the relationship between FIB-4 index and its independent variables is linear.

- In general, the FIB-4 index of the naïve/sham/ vehicle control treated animals tends to be far lesser than that of toxicant treated animals. Hepatoprotective substance exhibited FIB-4 index approximate to or less than that of the naive/vehicle /sham treated animals.

- The ratio of FIB-4 index of toxicant treated to FIB-4 of the naïve/sham/ vehicle control treated animals is greater than 1 with a negative linear correlation.

Platelet count may also be an early indicator of hepatotoxicity in experimental models of liver damage as such in curative studies, treatment should be initiated only after a decrease in platelet count is detected.

Conclusion

FIB-4 index is a quick, sensitive, objective index that can be employed in preclinical hepatic toxicology studies as an auxiliary and complimentary tool to aid in detecting hepatoactive substances. It has tremendous potential as a diagnostic tool and monitoring biomarker in studying the prognosis of hepatic damage or disorder without necessarily having to euthanize animals for analysis at every stage of the study.

Abbreviations

FIB-4: Fibrosis 4 index; AST: Aspartate Transaminase; ALT: Alanine Transaminase; APRI: AST to Platelet Ratio Index; APAP: Paracetamol; CCL4: Carbon Tetrachloride; INH: Isoniazid; RIF: Rifampicin; AUROC: Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve

Declarations

Ethical Statement

Not Applicable.

Funding

Authors had no funding.

Data availability

All data have been supplied.

Acknowledgement

The author acknowledges the help and advice of the late Nana Kweku Adu Sasu with this research work.

References

2. Lee WM. Drug-induced acute liver failure. Clinics in Liver Disease. 2013 Nov 1;17(4):575-86.

3. Alempijevic T, Zec S, Milosavljevic T. Drug-induced liver injury: Do we know everything?. World Journal of Hepatology. 2017 Apr 4;9(10):491.

4. Ostapowicz G, Fontana RJ, Schiødt FV, Larson A, Davern TJ, Han SH, et al. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2002 Dec 17;137(12):947-54.

5. Asrani SK, Devarbhavi H, Eaton J, Kamath PS. Burden of liver diseases in the world. Journal of Hepatology. 2019 Jan 1;70(1):151-71.

6. Jain M, Gilotra R, Mital J. Global trends of animal ethics and scientific research. Journal of Medicinal Plants. 2017;5(2):96-105.

7. Keane K. Histopathology in toxicity studies for study directors. The Role of the Study Director in Nonclinical Studies. 2014 Jun 6:275-96.

8. Titford M. The long history of hematoxylin. Biotechnic & Histochemistry. 2005 Jan 1;80(2):73-8.

9. Bedossa P, Dargère D, Paradis V. Sampling variability of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003 Dec;38(6):1449-57.

10. Bedossa P, Poynard T. An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1996 Aug;24(2):289-93.

11. Erdogan S, Dogan HO, Sezer S, Uysal S, Ozhamam E, Kayacetin S, et al. The diagnostic value of non-invasive tests for the evaluation of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B patients. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation. 2013 Jun 1;73(4):300-8.

12. Chen B, Ye B, Zhang J, Ying L, Chen Y. RDW to platelet ratio: a novel noninvasive index for predicting hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis B. PloS One. 2013 Jul 17;8(7):e68780.

13. Ma J, Jiang Y, Gong G. Evaluation of seven noninvasive models in staging liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2013 Apr 1;25(4):428-34.

14. Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Correa MC, Montaner J, et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006 Jun;43(6):1317-25.

15. Pak S, Kondo T, Nakano Y, Murata S, Fukunaga K, Oda T, et al. Platelet adhesion in the sinusoid caused hepatic injury by neutrophils after hepatic ischemia reperfusion. Platelets. 2010 Jan 1;21(4):282-8.

16. Zaldivar MM, Pauels K, von Hundelshausen P, Berres ML, Schmitz P, Bornemann J, et al. CXC chemokine ligand 4 (Cxcl4) is a platelet‐derived mediator of experimental liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2010 Apr;51(4):1345-53.

17. Kim BK, Kim DY, Park JY, Ahn SH, Chon CY, Kim JK, et al. Validation of FIB‐4 and comparison with other simple noninvasive indices for predicting liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in hepatitis B virus‐infected patients. Liver International. 2010 Apr;30(4):546-53.

18. Goldhamer SM, Isaacs R, Sturgis CC. The role of the liver in hematopoiesis. American Journal of Medical Sciences. 1934;188:193-9.

19. Wilson EM, Bial J, Tarlow B, Bial G, Jensen B, Greiner DL, et al. Extensive double humanization of both liver and hematopoiesis in FRGN mice. Stem Cell Research. 2014 Nov 1;13(3):404-12.

20. Miyakawa K, Joshi N, Sullivan BP, Albee R, Brandenberger C, Jaeschke H, et al. Platelets and protease-activated receptor-4 contribute to acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2015 Oct 8;126(15):1835-43.

21. Hugenholtz GC, Adelmeijer J, Meijers JC, Porte RJ, Stravitz RT, Lisman T. An unbalance between von Willebrand factor and ADAMTS13 in acute liver failure: implications for hemostasis and clinical outcome. Hepatology. 2013 Aug;58(2):752-61.

22. Lam FW, Rumbaut RE. Platelets mediate acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2015 Oct 8;126(15):1738-9.

23. Hernandez-Gea V, Friedman SL. Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease. 2011 Feb 28;6:425-56.

24. Khandoga A, Biberthaler P, Messmer K, Krombach F. Platelet–endothelial cell interactions during hepatic ischemia–reperfusion in vivo: a systematic analysis. Microvascular Research. 2003 Mar 1;65(2):71-7.

25. Lang PA, Contaldo C, Georgiev P, El-Badry AM, Recher M, Kurrer M, et al. Aggravation of viral hepatitis by platelet-derived serotonin. Nature Medicine. 2008 Jul;14(7):756-61.

26. Ovechkin AV, Lominadze D, Sedoris KC, Robinson TW, Tyagi SC, Roberts AM. Lung ischemia–reperfusion injury: implications of oxidative stress and platelet–arteriolar wall interactions. Archives of Physiology and Biochemistry. 2007 Jan 1;113(1):1-2.

27. Zaldivar MM, Pauels K, von Hundelshausen P, Berres ML, Schmitz P, Bornemann J, et al. CXC chemokine ligand 4 (Cxcl4) is a platelet‐derived mediator of experimental liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2010 Apr;51(4):1345-53.

28. Hesami Z, Jamshidzadeh A, Ayatollahi M, Geramizadeh B, Farshad O, Vahdati A. Effect of platelet-rich plasma on CCl 4-induced chronic liver injury in male rats. International Journal of Hepatology. 2014 Feb 23;2014.

29. Lam FW, Vijayan KV, Rumbaut RE. Platelets and their interactions with other immune cells. Comprehensive Physiology. 2015 Jul 7;5(3):1265-80.

30. Kaplowitz N. Biochemical and cellular mechanisms of toxic liver injury. InSeminars in liver disease 2002 (Vol. 22, No. 02, pp. 137-144). Copyright© 2002 by Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., 333 Seventh Avenue, New York, NY 10001, USA. Tel.:+ 1 (212) 584-4662.

31. Tarrats N, Moles A, Morales A, García‐Ruiz C, Fernández‐Checa JC, Marí M. Critical role of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, but not 2, in hepatic stellate cell proliferation, extracellular matrix remodeling, and liver fibrogenesis. Hepatology. 2011 Jul;54(1):319-27.

32. Morio LA, Chiu H, Sprowles KA, Zhou P, Heck DE, Gordon MK, et al. Distinct roles of tumor necrosis factor-α and nitric oxide in acute liver injury induced by carbon tetrachloride in mice. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2001 Apr 1;172(1):44-51.

33. Czaja MJ, Xu J, Alt E. Prevention of carbon tetrachloride-induced rat liver injury by soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor. Gastroenterology. 1995 Jun 1;108(6):1849-54.

34. Rej R, Shaw LM. Measurement of aminotransferases: Part 1. Aspartate aminotransferase. CRC Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences. 1984 Jan 1;21(2):99-186.

35. Price C, Albert K. Biochemical Assessment of Liver Function. Liver and Biliary Diseases—Pathophysiology, Diagnosis. Management. WB Saunders: London. 1979.

36. Panteghini M. Aspartate aminotransferase isoenzymes. Clinical Biochemistry. 1990 Aug 1;23(4):311-9.

37. Dufour DR, Lott JA, Nolte FS, Gretch DR, Koff RS, Seeff LB. Diagnosis and monitoring of hepatic injury. I. Performance characteristics of laboratory tests. Clinical Chemistry. 2000 Dec 1;46(12):2027-49.

38. Zhijian Y, Hui L, Weiming Y, Zhanzhou L, Zhong C, Jinxin Z, et al. Role of the aspartate transaminase and platelet ratio index in assessing hepatic fibrosis and liver inflammation in adolescent patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology Research and Practice. 2015 Jul 5;2015.

39. Senthilkumar R, Chandran R, Parimelazhagan T. Hepatoprotective effect of Rhodiola imbricata rhizome against paracetamol-induced liver toxicity in rats. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2014 Nov 1;21(5):409-16.

40. Ujah OF, Ipav SS, Ayaebene CS, Ujah IR. Phytochemistry and hepatoprotective effect of ethanolic leaf extract of Corchorus olitorius on carbon tetrachloride induced toxicity. European Journal of Medicinal Plants. 2014;4(8):882-92.

41. Dwivedi V, Mishra J, Shrivastava A. Efficacy study of livartho against paracetamol induced hepatotoxicity in adult Sprague Dawley rats. J Drug Metab Toxicol. 2015;5(6):175-81.

42. Bera TK, Chatterjee K, De D, Ali KM, Jana K, Maiti S, et al. Hepatoprotective activity of Livshis, a polyherbal formulation in CCl4-induced hepatotoxic male Wistar rats: a toxicity screening approach. Genomic Medicine, Biomarkers, and Health Sciences. 2011 Sep 1;3(3-4):103-10.

43. Nwidu LL, Elmorsy E, Oboma YI, Carter WG. Hepatoprotective and antioxidant activities of Spondias mombin leaf and stem extracts against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences. 2018 Jun 1;13(3):262-71.

44. Iroanya OO, Adebesin OA, Okpuzor J. Evaluation of the Hepato and Nephron-Protective Effect of a Polyherbal Mixture using Wistar Albino Rats. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014 Jun;8(6):HC15-21.

45. Tzankova V, Aluani D, Kondeva-Burdina M, Yordanov Y, Odzhakov F, Apostolov A, et al. Hepatoprotective and antioxidant activity of quercetin loaded chitosan/alginate particles in vitro and in vivo in a model of paracetamol-induced toxicity. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy. 2017 Aug 1;92:569-79.

46. El-Megharbel SM, Hamza RZ, Refat MS. Preparation, spectroscopic, thermal, antihepatotoxicity, hematological parameters and liver antioxidant capacity characterizations of Cd (II), Hg (II), and Pb (II) mononuclear complexes of paracetamol anti-inflammatory drug. spectrochimica acta part a: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2014 Oct 15;131:534-44.

47. Payasi A, Chaudhary M, Singh BM, Gupta A, Sehgal R. Sub-acute toxicity studies of paracetamol infusion in albino wistar rats. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Drug Research. 2010;2(2):142-5.

48. Shanmugam S, Thangaraj P, dos Santos Lima B, Chandran R, de Souza Araújo AA, Narain N, et al. Effects of luteolin and quercetin 3-β-d-glucoside identified from Passiflora subpeltata leaves against acetaminophen induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2016 Oct 1;83:1278-85.

49. Johnson M, Olufunmilayo LA, Anthony DO, Olusoji EO. Hepatoprotective effect of ethanolic leaf extract of Vernonia amygdalina and Azadirachta indica against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in Sprague-Dawley male albino rats. American Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 2015;3(3):79-86.

50. Chavan TC, Kuvalekar AA. A review on drug induced hepatotoxicity and alternative therapies. Journal of Nutrition Health Food Sciences. 2019;7(3):1-29.

51. Rashid U, Khan MR, Sajid M. Hepatoprotective potential of Fagonia olivieri DC. against acetaminophen induced toxicity in rat. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2016 Dec;16(1):449.

52. Aziz A, Khaliq T, Khan JA, Jamil A, Majeed W, Faisal MN, et al. Ameliorative effects of Qurs-e-afsanteen on gentamicin induced hepatotoxicity and oxidative stress in rabbits. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Sciences. 2017 Mar 1;54(1).

53. Aroonvilairat S, Tangjarukij C, Sornprachum T, Chaisuriya P, Siwadune T, Ratanabanangkoon K. Effects of topical exposure to a mixture of chlorpyrifos, cypermethrin and captan on the hematological and immunological systems in male Wistar rats. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2018 Apr 1;59:53-60.

54. Nwidu LL, Teme RE. Hot aqueous leaf extract of Lasianthera africana (Icacinaceae) attenuates rifampicin-isoniazid-induced hepatotoxicity. Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2018 Jul 1;16(4):263-72.

55. Nwidu LL, Oboma YI. Telfairia occidentalis (Cucurbitaceae) pulp extract mitigates rifampicin-isoniazid-induced hepatotoxicity in an in vivo rat model of oxidative stress. Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2019 Jan 1;17(1):46-56.

56. Atmaca N, Yıldırım E, Güner B, Kabakçı R, Bilmen FS. Effect of resveratrol on hematological and biochemical alterations in rats exposed to fluoride. BioMed Research International. 2014 Jun 5;2014.

57. Ismail HA, Hamza RZ, El-Shenawy NS. Potential protective effects of blackberry and quercetin on sodium fluoride-induced impaired hepato-renal biomarkers, sex hormones and hematotoxicity in male rats. J Appl Life Sci Intern. 2014;1(1):1-6.

58. Bouasla A, Bouasla I, Boumendjel A, Abdennour C, El Feki A, Messarah M. Prophylactic effects of pomegranate (Punica granatum) juice on sodium fluoride induced oxidative damage in liver and erythrocytes of rats. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 2016;94(7):709-18.

59. Chen Q, Xue Y, Sun J. Hepatotoxicity and liver injury induced by hydroxyapatite nanoparticles. Journal of Applied Toxicology. 2014 Nov;34(11):1256-64.

60. Abdel-Ghaffar O, Ali AA, Soliman SA. Protective effect of naringenin against isoniazid-induced adverse reactions in rats. International Journal of Pharmacology. 2018 Jan 1;14(5):667-80.

61. Hussain A, Aslam B, Gilani MM, Khan JA, Anwar MW. Biochemical and histopathological investigations of hepatoprotective potential of Phoenix dactylifera against isoniazid induced toxicity in animal model. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Sciences. 2019 Apr 1;56(2).

62. Mary Momo CM, Ferdinand N, Omer Bebe NK, Alexane Marquise MN, Augustave K, Bertin Narcisse V, et al. Oxidative effects of potassium dichromate on biochemical, hematological characteristics, and hormonal levels in rabbit doe (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Veterinary sciences. 2019 Mar 18;6(1):30.

63. Oshida K, Iwanaga E, Miyamoto-Kuramitsu K, Miyamoto Y. An in vivo comet assay of multiple organs (liver, kidney and bone marrow) in mice treated with methyl methanesulfonate and acetaminophen accompanied by hematology and/or blood chemistry. The Journal of Toxicological Sciences. 2008 Dec 1;33(5):515-24.