Commentary

The NOTCH receptors are mechanosensing proteins that require cell-cell contact and physical force for activation. While most receptors have evolved to respond to one or a few unique ligands, the four NOTCH receptors can respond to any of the five Delta/Serrate/Lag-2 (DSL) ligands - Jagged (JAG) 1, 2, and Delta-like (DLL) 1, 3, 4 [1]. What is most surprising is that unlike receptors that can have bias signaling, such as G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), by acquiring different conformations, the NOTCH receptors become activated by proteolysis upon pulling of the extracellular domain by any of the ligands, resulting in the proteolytic cleavage by membrane proteases (notably gamma-secretase) releasing the Notch Intracellular Domain (NICD) [2] – which is a common final outcome of NOTCH activation no matter the ligand at play. Once released, the NICD translocates to the nucleus to complex with CSL and other factors to regulate NOTCH-target genes.

Each NOTCH exhibits both individual and overlapping activities, unsurprisingly, considering their critical roles in development and tissue maintenance. Yet, the fact that different ligands activate different responses in the same receptor, we confess, sounds absurd. Nevertheless, mounting evidence shows that the downstream responses, including metabolic and gene expression changes in the receiving cell, depend on the type of ligand [3,4].

One possible explanation is that the interactions between ligands and receptors affect the velocity of activation, resulting in varied kinetics. Some ligands cause rapid activation with large pulses, while others trigger slower, more continuous signaling. Indeed, studies on NOTCH1 activation in individual cells have brought to light the intriguing fact that DLL1 and DLL4 generate distinct gene expression outcomes in the receiving cell [4]. DLL1 induces periodic pulses of Notch activation, while DLL4 induces sustained activity over time, resulting in similar HES1 gene expression but notably higher HEY1 and HEYL gene expression by DLL4 versus DLL1.

Could the observed differences in cell responses be attributed to variations in the affinity of ligands for NOTCH receptors? Notably, DLL4 binds to the NOTCH1 extracellular domain (ECD) with higher affinity than either DLL1 or JAG1, potentially accounting for the divergent strength of activation [5,6]. Quantitative analyses have further confirmed that higher affinity ligands indeed lead to more potent activation [7].

Moreover, studies involving in vitro evolved DLL4 ligands, engineered to approach NOTCH with up to a staggering 1,000-fold increase compared to wild-type (WT) DLL4, have exposed the connection between enhanced binding affinity and downstream responses - tested on cell lines expressing NOTCH1 utilizing a luciferase reporter integrated under the control of a CSL-driven promoter [8].

Thus, it has become evident that the mechanics of ligand activation revolve around the intriguing generation of different 'pulling' forces. This implies that some ligands may engage with the receptor for extended periods without immediate activation, while others bind and activate rapidly. Evidence supporting this notion can be observed in the case of JAG1, which necessitates higher molecular tension to activate NOTCH1 compared to DLL4. Upon binding NOTCH1, JAG1 undergoes conformational changes and remains bound for a sufficient duration to exert the force required to expose the S2 site for cleavage [5]. Furthermore, the interactions between ligands and structural proteins, exemplified by the interaction between JAG and vimentin, serve to further amplify the 'pulling' force required for effective signaling. Conversely, the absence of interaction between DLL and vimentin highlights the nuanced differences in ligand-receptor dynamics within the Notch pathway [9]. In the context of vasculature, this interaction is regulated by sheer stress, which upregulates JAG1 levels and promotes vimentin phosphorylation. Consequently, phosphorylated vimentin exhibits an enhanced interaction with JAG1, further increasing NOTCH transactivation [9].

Another layer of complexity lies in the numbers of engaged receptors and ligands, and their membrane organization, as oligomerization of both has been reported [4,10,11]. An open question is whether there are differences in NOTCH activity if they are activated in clusters, or in freely diffused on the membrane, and whether they are activated on one side or the other of polarized cells, or if membrane bending plays a role in downstream responses [12].

In addition to the number of receptors, the ligand-receptor ratio and the co-expression of ligands and receptors on the same cell are also critical factors to consider. Ligands in cis-conformation, when present on the same cell as the receptor, may compete with ligands presented by another cell in trans [13]. There is evidence that cis-conformation, facilitated by cluster formation between receptor and ligands, reduces Notch activity [13-15]. Interestingly, studies involving the experimentally controlled production of DLL1/4 and constantly expressed NOTCH have shown that while extreme expression of DLL1/4 silenced NOTCH activity, the intermediate DLL1/4 expression maximized cis-activation [4] – an observation that underscores the significance of the DLL1/4 expression threshold in finely regulating Notch signaling outcomes.

Although there are still key links missing in our understanding NOTCH activation dynamics, several independent approaches have been developed to address some of these questions. One such approach involves spatially controlling NOTCH activation by attaching the ligands (DLL or JAG) to inert surfaces. Thanks to bioprinting and micro-array technologies, these modified ligands – often engineered with the Fc of an antibody to anchor them to protein A- or protein G-coated surfaces (functionalized surfaces), can be placed in different concentrations, patterns and/or densities [16,17] (Figure 1). Likewise, the Synthetic Notch (SynNotch) concept was engineered by using artificial ligands, such as GFP, and exchanging the NOTCH ECD by that on a nanobody [18] (Figure 1). These approaches help explore how ligand number, pattern, and spatial arrangement affect the dynamics of NOTCH activation. Also, the use of nanobodies to target artificial ligands is of particular interest as they possess different affinities for either the same or different epitopes, making them useful for competition or orthogonal assays [19].

Figure 1: Illustrations of canonical NOTCH activation by neighboring cell (signaling cell) and by ligand-coated surface. Upon DLL/JAG ligand binding NOTCH undergoes proteolytic cleavage and its intracellular domain (NICD) is released to cytoplasm (left). Representation of ligand-functionalized materials, whether arranged in specific patterns or randomly, offers a more detailed understanding of the molecular constraints for activation (green spots). Natural or artificial ligands can be used to activate either WT NOTCH or SynNotch, respectively, leading to the release of NICD or a transcription factor acting as NICD (right). It is unclear whether aggregation or patterns make a difference in downstream signaling, yet the number of activating ligands does increase downstream signaling (downward arrows).

Despite the elegance of these techniques, to study the force-speed of activation is not possible using inert ligand-coated surfaces, just as controlling the number of receptor or ligands between cell-cell contacts. One could imagine that atomic force microscopy (AFM) could be used for this, but its limitation of analyzing one cell at the time hinders broader applications. So far, AFM has provided some data on strong adhesion forces between Delta and NOTCH, indicating a potential mechanism to enhance Notch signaling. However, further experiments are necessary to discern the differences in activation dynamics between various NOTCH ligands [20].

While the individual receptor activation has been addressed by exchanging the ECD of NOTCH with biorecognition molecules (aptamers, antibodies, dimerizing proteins, etc) [21-23], other challenges remain such as the timing, and more importantly, the patterns of activation.

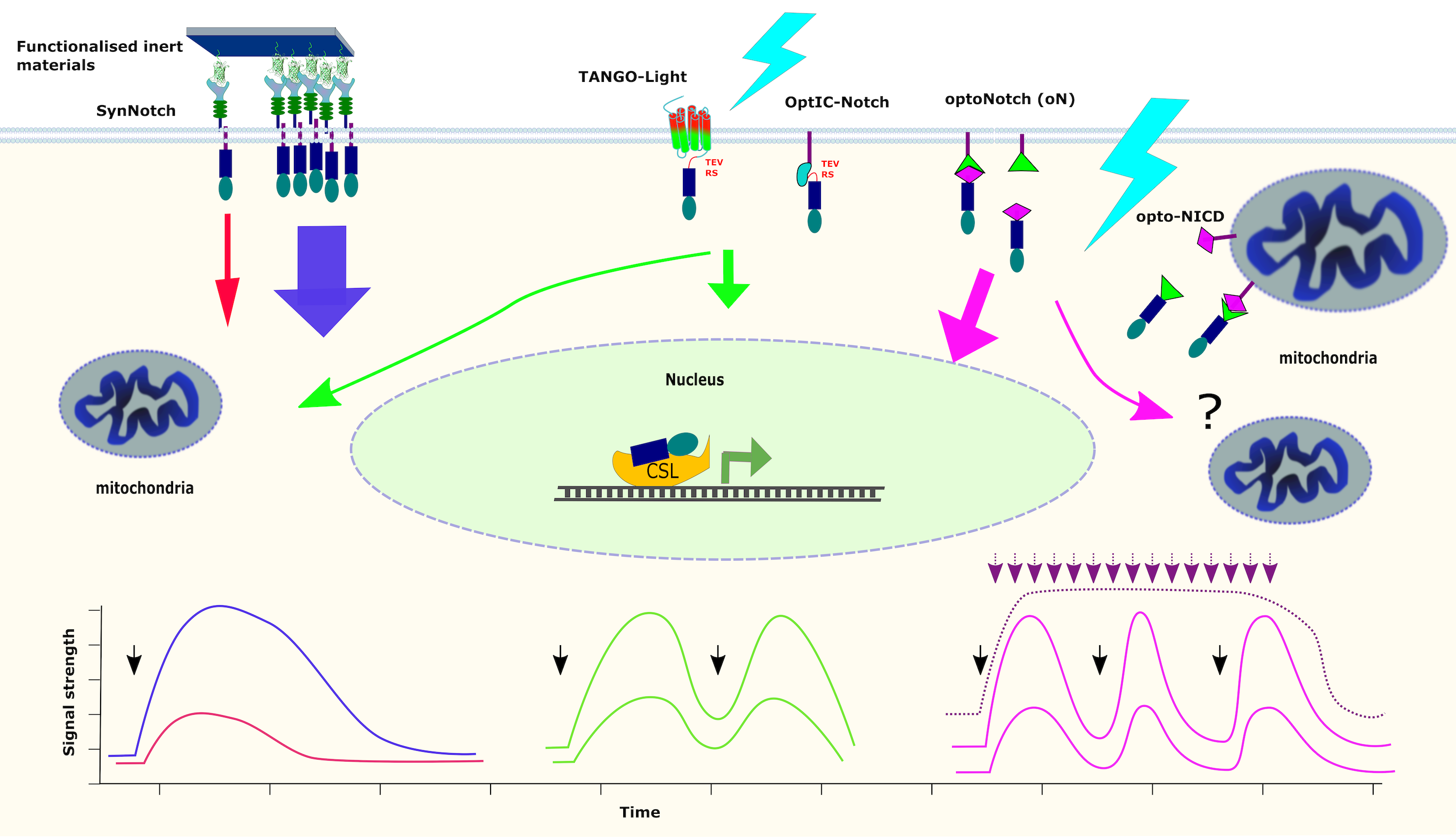

Thus, to overcome these limitations, we and others [24-26] have engineered NOTCH systems that are both ligand-independent and gamma-secretase-independent and can be controlled by light irradiation (Figure 2). The first reported system was an optogenetic inhibitor of Notch signaling, exploiting the abovementioned ligand in cis-conformation clustering effect. Clustering was achieved by a chimera between DLL and CRY2, a known optogenetic protein that aggregates or binds to CIB1 upon light activation [27]. Thus, Opto-Delta induced agglomeration of the ligand efficiently blocking NOTCH activation (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Optogenetic tools controlling Notch signaling. In opto-Delta, the signal sending cell expresses CRY2 photoreceptor fused with DLL4, and aggregates upon blue light irradiation increasing the ligand density leading to inhibition of Notch signaling in the receiving cell. TANGO-Light is composed of membrane anchored chimera of photoactivatable-CXCR4 receptor (PA-CXCR4) fused with the C-terminal of the vasopressin receptor containing a TEV protease recognition site (TEV RS) and NICD. Upon activation, PA-CXCR4 recruits β-arrestin-TEV, resulting in the proteolytical release of NICD from the plasma membrane. In optIC-Notch NICD is anchored to cell membrane with CIB1 and LOV (Light Oxygen Voltage) masking the TEV RS, and one half of TEV protease (not shown for simplicity). In the dark, this complex cannot bind with CRY2-complementing half TEV fusion protein present in the cytoplasm. Under blue light two phenomena occur: 1) CRY2 and CIB1 form a heterodimer, reconstituting TEV protease, and 2) unfolding of LOV, uncovering the TEV RS resulting in proteolytical release of NICD from the membrane. Opto-Notch (oN) and Drosophila opto-NICD consisting of NICD fused to one partner of the heterodimeric photoreceptor protein LOV2/ Zdk1 (Zdark 1), which dissociate under blue light stimulation. In oN, LOV2 (green triangle) protein is anchoring the complex to cell membrane, in Drosophila system Zdk1 (magenta diamond) is anchored to mitochondrial membrane. Upon light irradiation NICD-Zdk1 in oN /NICD –LOV2 in opto-NICD, is released from the membrane. Black arrows show that the system is unidirectional or reversible. Dotted line means the reverse process is slower.

Almost at the same time, two other optogenetic controlling systems for Notch were reported, one in Drosophila (opto-NICD) [25] and one for mammalian cells (optoNotch, oN) [24]. In both cases, the NICD was fused to the photoreceptor protein LOV2 (Light Oxygen Voltage 2) and Zdk1 (Zdark 1) in-dark heterodimerizing complex, which dissociates under blue light stimulation. In oN, LOV2 protein is anchoring the complex to the intracellular side of the plasma membrane, while in opto-NICD, it is Zdk1 the one anchored but to the mitochondrial outer membrane. In the dark the complexes NICD-Zdk1-LOV2 keep NICD unable to reach nucleus to do its transcriptional activities. Upon light irradiation Zdk1 and LOV2 dissociate from each other, releasing NICD-Zdk1 in oN and NICD-LOV2 in opto-NICD (Figure 2), enabling their translocation to the nucleus and triggering transcription of their target genes.

One must point out that these systems contain NICDs that carry a cargo with them, and although both are reported to activate downstream genes, it is unclear whether all their functions remain intact. More recently, two additional photoactivatable NOTCH systems have been reported: TANGO-Light (TL) [28] - a tool created by combining the TANGO system [29], a photoactivatable- CXCR4 receptor (PA-CXCR4) [30] and NICD, where light activation causes conformational changes in PA-CXCR4, leading the recruitment of a β-arrestin-TEV protease fusion. The latter cleaves the TEV recognition site (TEV RS in Figure 2) releasing the NICD (Figure 2). A somehow similar system (Opt-IC Notch) was engineered by a multi-chimera between a membrane-tethered CIB1, LOV-TRAP, a complementing half of TEV and NICD. For activation, another protein construct comprising CRY2 and the complementing half of TEV protease is expressed in the cytoplasm. Upon light stimulation, CRY2 binds to CIB1, bringing together the complementing TEV halves, triggering the proteolytical release of NICD (Figure 2). On both of these cases the NICD has only one amino acid cargo.

Optogenetic systems allow studying strength, frequency, and pattern of the activation by modulation of light irradiation intensity, as well as number and frequency of the light pulses over time. This is the only available approach enabling a full explanation of the role of different patterns of activation of NOTCH receptors in vitro and in vivo. Surprisingly, using light-inducible systems, one would expect that a greater number of light pulses will result in a higher reporter’s response. However, activity of Drosophila opto-NICD after an initial increase slowly decreases despite maintaining photo-stimulation [25]. The same response was observed in oN and TL suggesting negative feedback mechanism [24,28].

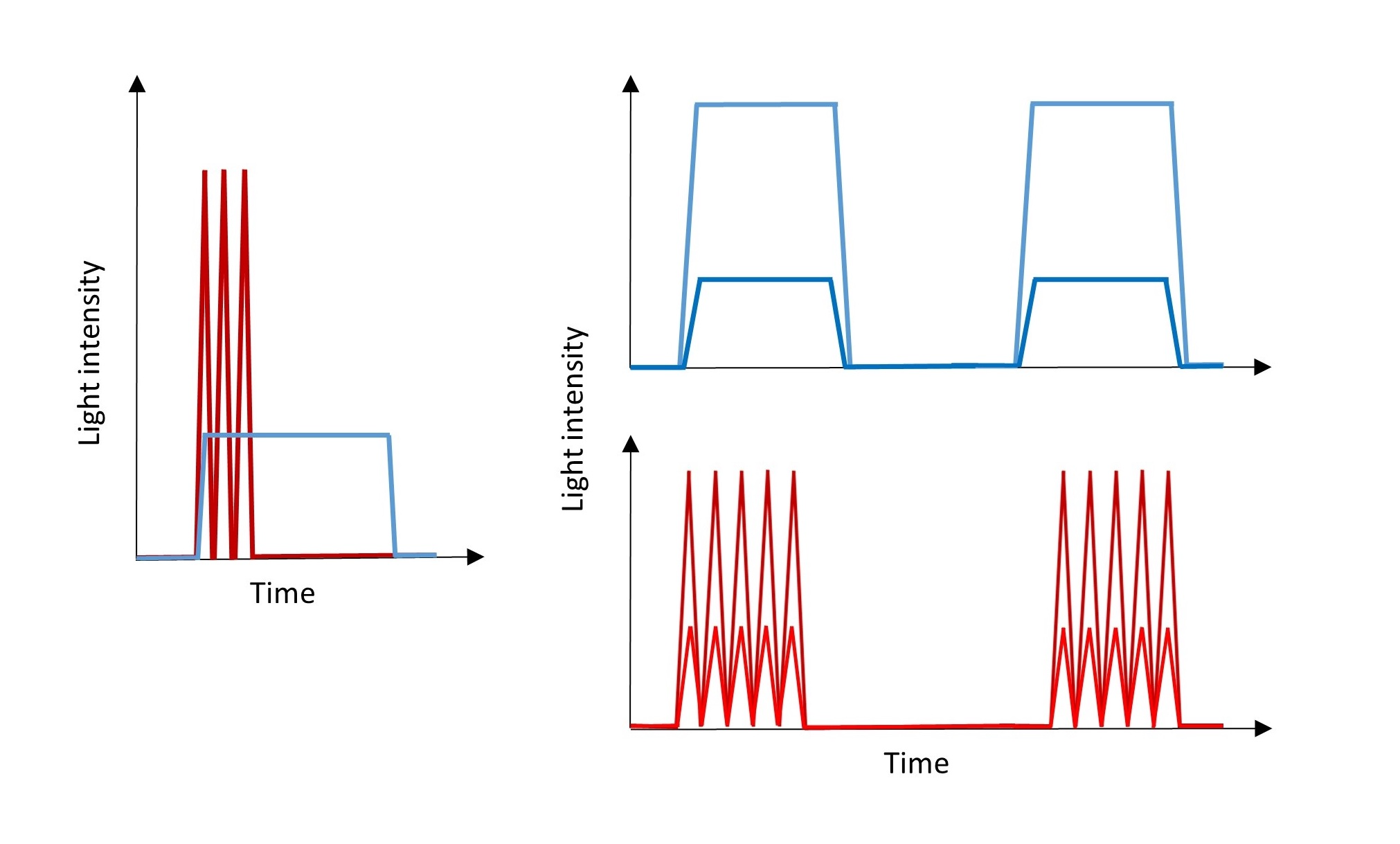

Knowing the different velocity of Notch activation by JAG1, DLL1, and DLL4, several light irradiation patterns shall be considered and tested to identify those that match the activation dynamics of the natural ligands (Figure 3). Whereas, for slow activation less intensive and prolonged light pulses at long time intervals, an increased number of more intensive and short light pulses at short time intervals might be used for fast activation. Also, patterns exhibiting features of both above models might be analyzed. Thereby oN, by creating various patterns of irradiation, enables fine-tuning of Notch signaling and, combined with RNA sequencing or ChIP (chromatin immunoprecipitation), may deliver functionally detailed data on Notch activation.

Figure 3: Light irradiation patterns for sustained (blue) and pulsatile (red) oN activation differing with the strength of activation.

All systems have their limitations, and opto-Notch systems are no exception. One of the limitations is that oN’s distribution, either on the cell membrane or around mitochondria, is unnatural and, for example, aggregates might not be achievable. However, the local activation, by illuminating part of the cell, is possible to study. In a way, these systems are a notch above those using functionalized surfaces, as optogenetic tools add timing, what is not possible with inert surfaces-coated ligands, at least considering plating cells on them as time zero, or the addition of an aptamer e.g., dimerizing or linking molecule.

Also, optoNotch’s, or functionalized surfaces’, independence from the signal-sending cell obviously miss the cell context. In addition to any effects on the sending-cell that would naturally occur in cell-cell Notch activation, an issue that remains unclear [31]. It cannot be ruled out that other factors, such as mechanical and physical bending of the membrane, may contribute to the overall Notch signaling pathway as well [32-34].

The commonly measured outcome of NOTCH activation is the expression of NOTCH-target genes. Although, there is also evidence that the cleaved NICD interacts with mitochondria and affects its metabolic functions [35-37]. Therefore, the impact of how synthetic NOTCH systems affect the mitochondria-related function of NICD remains unsolved (Figure 4). In oN and Drosophila opto-NICD, the Zdk2/ LOV2 cargo, respectively, might affect NICD mitochondrial activities, while in TL and Opt-IC Notch the proteolytical cleavage by TEV results in only an additional glycine at the N-terminus of NICD, likely having little effect on such activities. This is not a problem encountered in the synNotch approach where the NICD – usually exchanged by a transcriptional activator such as tTA or Gal4, would be released in the WT form, such approach has not been implemented as far as we can tell.

Figure 4: A comparison of Notch signaling responses in nucleus and mitochondria to activation by either ligand-coated materials, TANGO-Light (TL), Opt-IC Notch, oN or optoNICD systems. Plots represent the predicted dynamics of NICD response to the activation by GFP-synNotch (blue and red), TANGO-Light and optIC-Notch (green) and oN (magenta). Colors of arrows correspond to colors of the plots. Black arrows correspond to the input light pulse(s).

Finally, the leftover transmembrane domain (TMD) has been shown to have some signaling activity on its own [38]. Studies on vascular barrier revealed that the TMD left after NOTCH activation by sheer stress, forms a complex with vascular endothelial cadherin, the transmembrane protein tyrosine phosphatase LAR, and the Rac1 GEF Trio. This complex activates Rac1 to promote cell-cell junction assembly and establish the vascular barrier integrity [38]. These events are not represented in the opto-Notch systems but exist in those using SynNotch or ligand-functionalized surfaces.

As we have described above, there is no single magic tool to fully characterize all of Notch signaling effects. But all these tools have begun, notch by notch, to draw a detailed picture of how cells interpret NOTCH activation. Further development and refinement of these techniques will be needed to fully understand the complexity of Notch signaling in living organisms.

Funding

The work was funded by grants by the Polish National Science Centre (NCN): UMO-2017/25/B/NZ4/02364 and a grant by Medical University of Lublin GI/12.

References

2. Bray SJ. Notch signalling: a simple pathway becomes complex. Nature reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2006 Sep 1;7(9):678-89.

3. Bi P, Kuang S. Notch signaling as a novel regulator of metabolism. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2015 May 1;26(5):248-55.

4. Nandagopal N, Santat LA, LeBon L, Sprinzak D, Bronner ME, Elowitz MB. Dynamic ligand discrimination in the notch signaling pathway. Cell. 2018 Feb 8;172(4):869-80.

5. Luca VC, Kim BC, Ge C, Kakuda S, Wu D, Roein-Peikar M, et al. Notch-Jagged complex structure implicates a catch bond in tuning ligand sensitivity. Science. 2017 Mar 24;355(6331):1320-4.

6. Andrawes MB, Xu X, Liu H, Ficarro SB, Marto JA, Aster JC, et al. Intrinsic selectivity of Notch 1 for Delta-like 4 over Delta-like 1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013 Aug 30;288(35):25477-89.

7. Khamaisi B, Luca VC, Blacklow SC, Sprinzak D. Functional Comparison between Endogenous and Synthetic Notch Systems. ACS Synthetic Biology. 2022 Sep 15;11(10):3343-53.

8. Gonzalez-Perez D, Das S, Antfolk D, Ahsan HS, Medina E, Dundes CE, et al. Affinity-matured DLL4 ligands as broad-spectrum modulators of Notch signaling. Nature Chemical Biology. 2023 Jan;19(1):9-17.

9. van Engeland NC, Suarez Rodriguez F, Rivero-Müller A, Ristori T, Duran CL, Stassen OM, et al. Vimentin regulates Notch signaling strength and arterial remodeling in response to hemodynamic stress. Scientific Reports. 2019 Aug 27;9(1):12415.

10. Bardot B, Mok LP, Thayer T, Ahimou F, Wesley C. The Notch amino terminus regulates protein levels and Delta-induced clustering of Drosophila Notch receptors. Experimental Cell Research. 2005 Mar 10;304(1):202-23.

11. Nichols JT, Miyamoto A, Olsen SL, D'Souza B, Yao C, Weinmaster G. DSL ligand endocytosis physically dissociates Notch1 heterodimers before activating proteolysis can occur. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2007 Feb 12;176(4):445-58.

12. Morzy D, Bastings M. Significance of Receptor Mobility in Multivalent Binding on Lipid Membranes. Angewandte Chemie. 2022 Mar 21;134(13):e202114167.

13. Cordle J, Johnson S, Zi Yan Tay J, Roversi P, Wilkin MB, De Madrid BH, et al. A conserved face of the Jagged/Serrate DSL domain is involved in Notch trans-activation and cis-inhibition. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2008 Aug;15(8):849-57.

14. Sprinzak D, Lakhanpal A, LeBon L, Santat LA, Fontes ME, Anderson GA, et al. Cis-interactions between Notch and Delta generate mutually exclusive signalling states. Nature. 2010 May 6;465(7294):86-90.

15. Fiuza UM, Klein T, Martinez Arias A, Hayward P. Mechanisms of ligand‐mediated inhibition in Notch signaling activity in Drosophila. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2010 Mar;239(3):798-805.

16. Tiemeijer LA, Ristori T, Stassen OM, Ahlberg JJ, de Bijl JJ, Chen CS, et al. Engineered patterns of Notch ligands Jag1 and Dll4 elicit differential spatial control of endothelial sprouting. IScience. 2022 May 20;25(5):104306.

17. Tiemeijer LA, Frimat JP, Stassen OM, Bouten CV, Sahlgren CM. Spatial patterning of the Notch ligand Dll4 controls endothelial sprouting in vitro. Scientific Reports. 2018 Apr 23;8(1):6392.

18. Lee JC, Brien HJ, Walton BL, Eidman ZM, Toda S, Lim WA, et al. Instructional materials that control cellular activity through synthetic Notch receptors. Biomaterials. 2023 Jun 1;297:122099.

19. Cheloha RW, Fischer FA, Woodham AW, Daley E, Suminski N, Gardella TJ, et al. Improved GPCR ligands from nanobody tethering. Nature Communications. 2020 Apr 29;11(1):2087.

20. Ahimou F, Mok LP, Bardot B, Wesley C. The adhesion force of Notch with Delta and the rate of Notch signaling. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2004 Dec 20;167(6):1217-29.

21. Gordon WR, Zimmerman B, He L, Miles LJ, Huang J, Tiyanont K, et al. Mechanical allostery: evidence for a force requirement in the proteolytic activation of Notch. Developmental Cell. 2015 Jun 22;33(6):729-36.

22. Morsut L, Roybal KT, Xiong X, Gordley RM, Coyle SM, Thomson M, et al. Engineering customized cell sensing and response behaviors using synthetic notch receptors. Cell. 2016 Feb 11;164(4):780-91.

23. He L, Perrimon N. Synthetic Notch receptors and their applications to study cell-cell contacts in vivo. Developmental Cell. 2023 Feb 6;58(3):171-3.

24. Kałafut J, Czapiński J, Przybyszewska-Podstawka A, Czerwonka A, Odrzywolski A, Sahlgren C, et al. Optogenetic control of NOTCH1 signaling. Cell Communication and Signaling. 2022 May 18;20(1):67.

25. Viswanathan R, Hartmann J, Pallares Cartes C, De Renzis S. Desensitisation of Notch signalling through dynamic adaptation in the nucleus. The EMBO Journal. 2021 Sep 15;40(18):e107245.

26. Townson JM, Gomez-Lamarca MJ, Santa Cruz Mateos C, Bray SJ. OptIC-Notch reveals mechanism that regulates receptor interactions with CSL. Development. 2023 Jun 1;150(11):dev201785.

27. Viswanathan R, Necakov A, Trylinski M, Harish RK, Krueger D, Esposito E, et al. Optogenetic inhibition of Delta reveals digital Notch signalling output during tissue differentiation. EMBO Reports. 2019 Dec 5;20(12):e47999.

28. Przybyszewska-Podstawka A, Kalafut J, Czapinski J, Ngo TH, Czerwonka A, Rivero-Muller A. TANGO-Light-optogenetic control of transcriptional modulators. Biorxiv. 2023;2023.05.31.543150.

29. Lefkowitz RJ. A brief history of G‐protein coupled receptors (Nobel Lecture). Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2013 Jun 17;52(25):6366-78.

30. Lagerström MC, Schiöth HB. Structural diversity of G protein-coupled receptors and significance for drug discovery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2008 Apr;7(4):339-57.

31. Vázquez-Ulloa E, Lin KL, Lizano M, Sahlgren C. Reversible and bidirectional signaling of notch ligands. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2022 Jul 4;57(4):377-98.

32. Martins T, Meng Y, Korona B, Suckling R, Johnson S, Handford PA, et al. The conserved C2 phospholipid‐binding domain in Delta contributes to robust Notch signalling. EMBO Reports. 2021 Oct 5;22(10):e52729.

33. Stachowiak JC, Schmid EM, Ryan CJ, Ann HS, Sasaki DY, Sherman MB, et al. Membrane bending by protein–protein crowding. Nature Cell Biology. 2012 Sep;14(9):944-9.

34. Falo-Sanjuan J, Bray SJ. Membrane architecture and adherens junctions contribute to strong Notch pathway activation. Development. 2021 Oct 1;148(19):dev199831.

35. Lee SF, Srinivasan B, Sephton CF, Dries DR, Wang B, Yu C, et al. γ-Secretase-regulated proteolysis of the Notch receptor by mitochondrial intermediate peptidase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011 Aug 5;286(31):27447-53.

36. Hossain F, Sorrentino C, Ucar DA, Peng Y, Matossian M, Wyczechowska D, et al. Notch signaling regulates mitochondrial metabolism and NF-κB activity in triple-negative breast cancer cells via IKKα-dependent non-canonical pathways. Frontiers in Oncology. 2018 Dec 4;8:575.

37. Xu J, Chi F, Guo T, Punj V, Lee WP, French SW, et al. NOTCH reprograms mitochondrial metabolism for proinflammatory macrophage activation. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2015 Apr 1;125(4):1579-90.

38. Polacheck WJ, Kutys ML, Yang J, Eyckmans J, Wu Y, Vasavada H, et al. A non-canonical Notch complex regulates adherens junctions and vascular barrier function. Nature. 2017 Dec;552(7684):258-62.