Abstract

Buckminsterfullerene has inspired new research directions and potential applications in materials science, due to its spherical shape and unique physical and chemical properties. However, synthesizing all-metallic fullerene-like nanostructures remains challenging, given the complexities of the synthesis process and the discrepancies between experimental and theoretical predictions. Recently, Professor Wang Shuxin’s team from Qingdao University of Science and Technology and Professor Wu Zhennan’s team from Jilin University disclosed in Nature Synthesis the synthesis, structure, and optical properties of Ag135Cu60(S(CH2)2Ph)60Cl42 (abbreviated as Ag135Cu60), the first metal nanocluster to incorporate a buckminsterfullerene-like topology moiety. This bimetallic nanocluster exhibits unique optical absorption and hybrid molecular-metallic characteristics, providing a new platform for investigating topological structure and atomic-scale assembly of metal nanoclusters.

Keywords

Metal nanoclusters, Buckminsterfullerene-like topology, Metallic and molecular states

Commentary

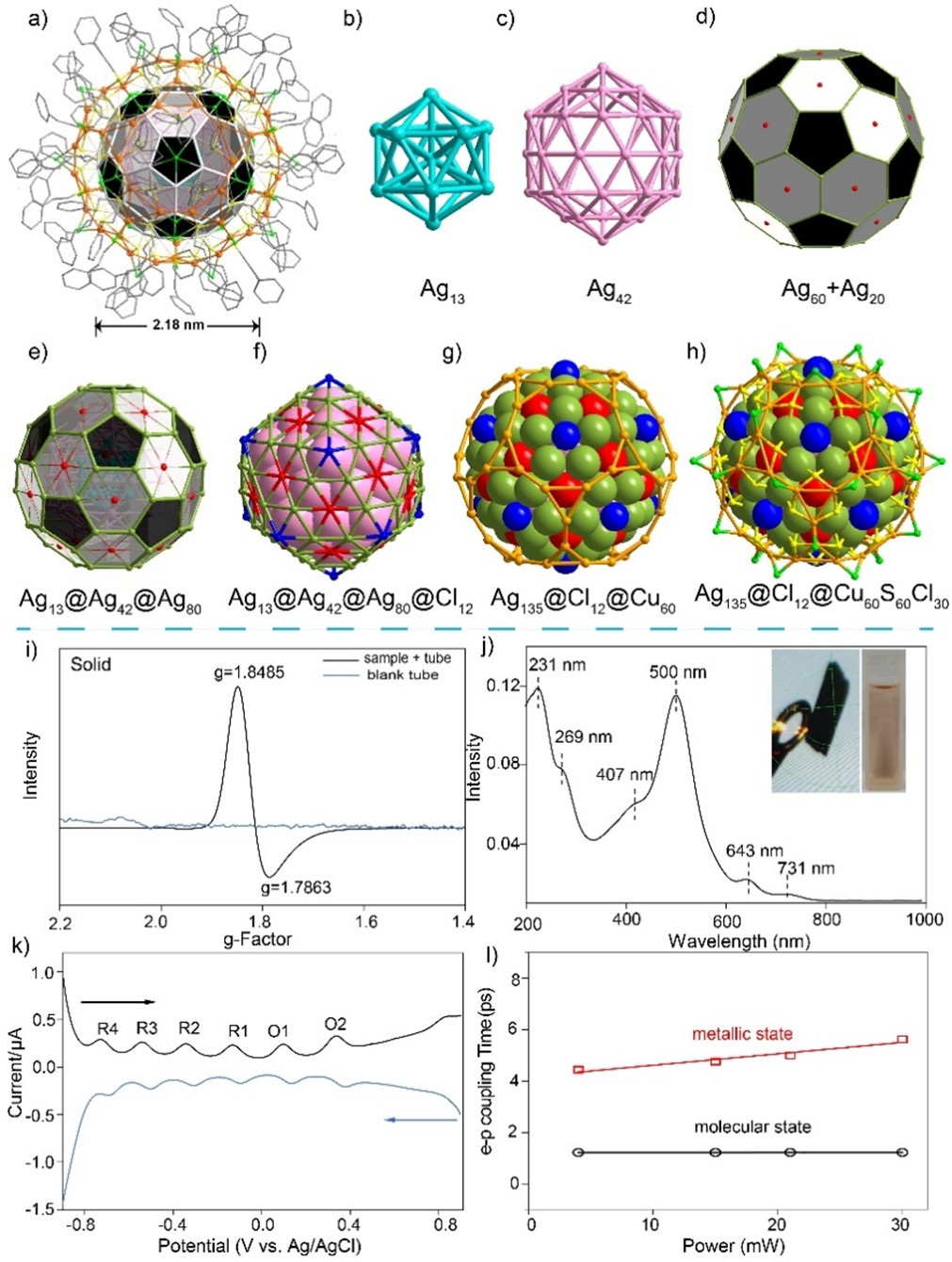

Metal nanoclusters, serving as a mesoscopic bridge between discrete atoms and bulk materials, have emerged as a frontier in the convergence of coordination chemistry and material science [1-16]. Organic ligand-protected metal nanoclusters, with well-defined atomic compositions, unique geometric topologies, and tunable properties, show great potential in catalysis, sensing, and energy conversion [17-33]. Platonic and Archimedean polyhedra-based geometric analysis reveals structure-property relationships in these clusters [34-45]. Early breakthroughs focused on the construction of fullerene-mimetic cage clusters. For instance, Burns et al. successfully synthesized the U60Ox30 cage cluster with buckminsterfullerene (C60)-like topology by bridging uranyl hexagonal bipyramids with oxalate ligands [45]. However, research on polynuclear metal nanoclusters remains relatively limited, primarily due to the intrinsic instability of non-carbon-based fullerenes. The long-predicted “golden fullerene” Au32, first theorized in 2004, [46] was not realized until 2019 when Wang’s team achieved its synthesis using a dual-ligand protection strategy [47]. Subsequently, Schnepf’s group expanded the structural diversity of the Au32 family through a NaBH4 reduction approach [48]. Notably, Zintl-type triple-shell clusters, such as [K@Au12Sb20]5−[49]and [Sb@Pd12@Sb20]n− [50], exhibit near-spherical icosahedral frameworks but suffer from structural collapse due to the lack of ligand stabilization. These advancements highlight a key challenge: balancing geometric perfection and chemical stability hinders atomic-level assembly of metal fullerene nanoclusters. In a groundbreaking collaboration, the research teams led by Professor Shuxin Wang and Professor Zhennan Wu have recently published their latest findings in Nature Synthesis [51]. Leveraging the dynamic coordination of flexible ligands combined with the synergistic effects of halide ligands, the researchers successfully synthesized the largest Ag-Cu alloy nanocluster to date — Ag135Cu60. Comprehensive characterization using methods like UV-vis, EPR, DPV, and fs-TA revealed unique hybrid molecular-metallic properties, paving the way for in-depth exploration of its structural and functional correlations. Ag135Cu60 nanoclusters were synthesized by the one-pot method, and by optimizing the reaction conditions, such as reactant ratio, solvent selection, and stirring time, a yield of about 10.6% was obtained. This yield is considered intermediate in the synthesis of large core-shell metal nanoclusters. The choice of flexible thiol ligands and synergistic effect of ligands is critical for the formation of target clusters, as they provide more flexibility and adaptability. Flexible thiol ligands have more flexibility and adaptability, which can adapt to different surface geometry and size during the synthesis process to regulate the growth pattern and morphology of clusters. This adaptability is also beneficial for halogen access to the metal surface, promoting the stability and growth of large-sized nanoclusters. In addition, flexible ligands can mitigate static disorder and promote crystallization. The stability of the newly synthesized Ag135Cu60 nanoclusters is superior to that of the previously reported Au32 and K@Au12Sb20 nanoclusters. Ag135Cu60 nanoclusters can exist stably for more than 60 days at room temperature, while Au32 can only maintain for 40 days, [47] and K@Au12Sb20 nanoclusters decompose directly [49]. The Ag135Cu60 nanocluster has a smaller energy gap than the other two nanoclusters. However, in the process of synthesizing Ag135Cu60, its yield is only 10.6%, while the yields of the other two nanoclusters can reach 12% or even 25%. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SC-XRD) analysis reveals that the Ag135Cu60 nanocluster exhibits a distinctive five-layered core-shell architecture: a central Ag13@Ag42@Ag80 sandwich core, an intermediate Cl12 ligand layer, and an outer Cu60(S(CH2)2Ph)60Cl30 shell (Ag13@Ag42@Ag80@Cl12@Cu60(S(CH2)2Ph)60Cl30). This “Russian doll” -like hierarchical assembly not only endows the cluster with an axial dimension of 1.88 nm but also enables precise modulation of electron delocalization through graded variations in metal-metal bond lengths, laying a foundation for tailored property optimization (Figures 1a-1h). Further structural and electronic characterization confirms that Ag135Cu60 adopts a neutral open-shell configuration with 93 free electrons, consistent with theoretical calculations and validated by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy (Figure 1i). The UV-visible absorption spectrum exhibits multiple peaks, notably a prominent plasmon-like absorption band at 500 nm, distinct from the typical molecular-state transitions observed in conventional clusters (Figure 1j). Electrochemical measurements reveal a remarkably small HOMO-LUMO gap (~0.01 eV), which further supports its possible hybrid molecular-metallic nature (Figure 1k).

Femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy (fs-TA) is a powerful ultrafast optical technique for studying ultrafast dynamics of electronic states and energy transfer processes in materials, including nanoclusters. [52] Electron dynamics refers to the rapid evolution of electronic states in a material in response to external stimuli, such as light absorption or electric fields. Phonon coupling describes the interaction between electrons (or electronic states) and lattice vibrations (phonons) in a material. Phonons are quantized representations of the vibrational modes of atoms in a lattice. The key uses of femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy in the study of metallic nanomaterials are: (i) to reveal the rapid changes of electronic states (excitons, charge carriers, hot electron formation, and relaxation); (ii) to study the phonon coupling and energy transfer mechanism; (iii) to capture the dynamic behavior of the surface plasmon resonance; (iv) to understand size- and shape-dependent electronic and optical properties; (v) to provide basic data for photocatalysis and energy conversion applications. fs-TA elucidated the excited-state dynamics of the Ag135Cu60 nanocluster system (Figure. 1-l). The anomalous pump-power dependence and strong phonon coupling in Ag135Cu60 demonstrate that excited-state electron-phonon interactions play a pivotal role in modulating its electronic behavior. These distinctive structural vibrational attributes provide substantive experimental evidence for the dual metallic-molecular state characteristics intrinsic to this material system. This finding enhances our mechanistic understanding of hybrid state coexistence in noble metal nanoclusters. In summary, the successful synthesis of Ag135Cu60 nanoclusters represents a significant breakthrough in metallic nanocluster research, addressing the contemporary imperative for functional integration in nanomaterial development. This investigation not only achieves structural replication of non-carbon-based buckminsterfullerene (C60)-like topology but also demonstrates dual molecular-metallic state characteristics, thereby providing experimental validation for atomic-scale plasmonic resonance phenomena.

Building upon Professor Wang Shuxin’s team foundational studies of the Ag135Cu60 nanocluster, future research faces both opportunities and critical challenges:

Figure 1: Comprehensive structural (a-h) and optoelectronic (i-l) analysis of the Ag135Cu60 bimetallic nanocluster.

Opportunities

i) Surface Modification and Ligand Exchange: By altering surface ligands or conducting ligand exchange, we can further adjust and optimize the optical and electronic properties of Ag135Cu60 to meet varying application requirements. (ii) Effect of alloy: Introducing other metal elements for alloying can explore enhancements in specific applications, such as catalytic activity or electrical conductivity.

(iii) Catalysis: The potential of Ag135Cu60 in catalysis merits further exploration, especially in photocatalysis and electrocatalysis, such as electrocatalytic CO2 reduction.

(iv) Optoelectronics: Given its unique optical absorption properties, Ag135Cu60 has enormous potential in optoelectronic devices, such as photodetectors or solar cells. Future research will focus on its integration and performance optimization in these devices.

Challenges

The challenge of large-scale synthesis

(i) Optimization of Reaction Conditions: In large-scale production, we need to optimize the reaction conditions to ensure uniformity and repeatability.

(ii) Reaction Time and Cost Management: Large-scale production requires efficient reaction time to reduce production costs.

(iii) Product Purity and Consistency: We need to develop reliable purification processes and quality inspection methods to ensure that all batches of products achieve the required purity and consistency. This may involve optimization and standardization of multi-step purification processes such as crystallization, filtration and chromatography.

The challenges of integrating into actual devices

(i) Performance Retention and Compatibility: How to maintain the unique optical and electronic properties of Ag135Cu60 while achieving its compatibility with existing devices and materials. This requires us to deeply study the behavior and interface properties of nanoclusters on different substrate materials and consider possible chemical and physical interactions to design suitable encapsulation and integration schemes.

(ii) Environmental Stability: We need to study the stability and lifetime of nanoclusters in the face of more complex environments and may need to develop appropriate protective layers or encapsulation technologies to improve their environmental tolerance and long-term stability.

(iii) Functional Testing and Verification: After being integrated into the actual device, the functionality of Ag135Cu60 nanoclusters needs to be fully tested and verified, including its optical response, electrical properties and its performance in specific application scenarios. These tests help identify potential problems and guide further optimization and improvement. Through in-depth study and discussion of these opportunities and challenges, we believe that we will not only enhance our understanding and capabilities of Ag135Cu60 nanocluster properties but also drive significant advances in the development of multifunctional nanomaterials, especially for applications in catalysis and optoelectronics.

Acknowledgments

S.W. acknowledges the financial support provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22171156 and 21803001), the Taishan Scholar Foundation of Shandong Province, and Startup Foundation of Qingdao University of Science and Technology.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

2. Guan ZJ, Li JJ, Hu F, Wang QM. Structural Engineering toward Gold Nanocluster Catalysis. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2022 Dec 19;61(51):e202209725.

3. Jin R, Li G, Sharma S, Li Y, Du X. Toward Active-Site Tailoring in Heterogeneous Catalysis by Atomically Precise Metal Nanoclusters with Crystallographic Structures. Chem Rev. 2021 Jan 27;121(2):567-648.

4. Zhao H, Zhang C, Han B, Wang Z, Liu Y, Xue Q, et al. Assembly of air-stable copper (I) alkynide nanoclusters assisted by tripodal polydentate phosphoramide ligands. Nature Synthesis. 2024 Apr;3(4):517-26.

5. Ishii W, Okayasu Y, Kobayashi Y, Tanaka R, Katao S, Nishikawa Y, et al. Excited state engineering in Ag29 nanocluster through peripheral modification with silver (I) complexes for bright near-infrared photoluminescence. J Am Chem Soc. 2023 Apr 26;145(20):11236-44.

6. Chakraborty I, Pradeep T. Atomically Precise Clusters of Noble Metals: Emerging Link between Atoms and Nanoparticles. Chem Rev. 2017 Jun 28;117(12):8208-71.

7. Ma F, Abboud KA, Zeng C. Precision synthesis of a CdSe semiconductor nanocluster via cation exchange. Nature Synthesis. 2023 Oct;2(10):949-59.

8. Albright EL, Levchenko TI, Kulkarni VK, Sullivan AI, DeJesus JF, Malola S, et al. N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Stabilized Atomically Precise Metal Nanoclusters. J Am Chem Soc. 2024 Mar 6;146(9):5759-80.

9. Tang L, Luo Y, Ma X, Wang B, Ding M, Wang R, et al. Poly‐Hydride [AuI7 (PPh3)7H5](SbF6)2 cluster complex: Structure, Transformation, and Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction Properties. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2023 Mar 6;62(11):e202300553.

10. Shi CG, Jia JH, Jia Y, Li G, Tong ML. Bulky thiolate-protected silver nanocluster Ag213 (Adm-S) 44Cl33 with excellent electrocatalytic performance toward oxygen reduction. CCS Chemistry. 2023 May 1;5(5):1154-62.

11. Zhuang S, Liao L, Li MB, Yao C, Zhao Y, Dong H, et al. The fcc structure isomerization in gold nanoclusters. Nanoscale. 2017 Oct 12;9(39):14809-13.

12. Wei X, Shen H, Xu C, Li H, Jin S, Kang X, et al. Ag48 and Ag50 Nanoclusters: Toward Active-Site Tailoring of Nanocluster Surface Structures. Inorg Chem. 2021 Apr 19;60(8):5931-6.

13. Li B, Kang L, Lun Y, Yu J, Song S, Wang Y. Structure–performance relationship of Au nanoclusters in electrocatalysis: Metal core and ligand structure. Carbon Energy. 2024 Aug;6(8):e547.

14. Yi H, Song S, Han SM, Lee J, Kim W, Sim E, et al. Superatom-in-Superatom Nanoclusters: Synthesis, Structure, and Photoluminescence. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2023 Aug 14;62(33):e202302591.

15. Wang L, Yan X, Tian G, Xie Z, Shi S, Zhang Y, et al. Chiral copper-hydride nanoclusters: synthesis, structure, and assembly. Dalton Trans. 2023 Mar 14;52(11):3371-7.

16. Higaki T, Liu C, Zeng C, Jin R, Chen Y, Rosi NL, et al. Controlling the Atomic Structure of Au30 Nanoclusters by a Ligand-Based Strategy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016 Jun 1;55(23):6694-7.

17. Ge X, Zeng S, Deng H, Teo BK, Sun C. Atom-precise copper nanoclusters based on FCC, BCC, and HCP structures. Coord Chem Rev. 2024 Mar 15;503:215667.

18. Lethbridge S, Pavloudis T, McCormack J, Slater T, Kioseoglou J, Palmer RE. Stabilization of 2D raft structures of Au nanoclusters with up to 60 atoms by a carbon support. Small Science. 2024 Aug;4(8):2400093.

19. Zhu X, Zhu P, Cong X, Ma G, Tang Q, Wang L, et al. Atomically precise alkynyl-protected Ag19Cu2 nanoclusters: synthesis, structure analysis, and electrocatalytic CO2 reduction application. Nanoscale. 2024 Sep 19;16(36):16952-7.

20. Liu Z, Liu X, Qin L, Chen H, Li R, Tang Z. Alkynyl ligand for preparing atomically precise metal nanoclusters: Structure enrichment, property regulation, and functionality enhancement. Chinese Journal of Structural Chemistry. 2024 Jul 26:100405.

21. Zhu J, Zhao R, Shen H, Zhu C, Zhou M, Kang X, et al. Intramolecular Aggregation‐Induced Surface Coupling of Metal Nanoclusters: Structure Elucidation and Photoluminescence Manipulation. Aggregate. 2024:e720.

22. Zhang Y, Zhang W, Zhang TS, Ge C, Tao Y, Fei W, et al. Site-Recognition-Induced Structural and Photoluminescent Evolution of the Gold–Pincer Nanocluster. J Am Chem Soc. 2024 Mar 26;146(14):9631-9.

23. Yao Y, Hao W, Tang J, Kirschbaum K, Gianopoulos CG, Ren A, et al. Anomalous Structural Transformation of Cu (I) Clusters into Multifunctional CuAg Nanoclusters. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2024 Sep 2;63(36):e202407214.

24. Sun X, Wang Y, Wu Q, Han YZ, Gong X, Tang X, et al. Cu66 nanoclusters from hierarchical square motifs: Synthesis, assembly, and catalysis. Aggregate. 2025 Jan;6(1):e651.

25. Chen M, Guo C, Qin L, Wang L, Qiao L, Chi K, et al. Atomically Precise Cu Nanoclusters: Recent Advances, Challenges, and Perspectives in Synthesis and Catalytic Applications. Nanomicro Lett. 2025 Dec;17(1):83.

26. Guo Y, Zhang Z, Han H, Zhou Z. Chiral Separation of Copper Sulfide [S–Cu36] Nanocluster Using a Chiral Adaptive Counterion. Nano Lett. 2024 Sep 6;24(38):11985-91.

27. Yao Q, Zhu M, Yang Z, Song X, Yuan X, Zhang Z, et al. Molecule-like synthesis of ligand-protected metal nanoclusters. Nat Rev Mater. 2025;10:89-108.

28. Yang T, Jia J, Xiong L, Jin S, Zhu M. [Cu58 (SeC6H5)24 (Dppe)6 Se16] 2+ assembled from tetrahedra and octahedra: synthesis, characterization, structure and catalytic properties. Chem Commun. 2024;60(71):9614-7.

29. Yang M, Zhu L, Yang W, Xu W. Nucleic acid-templated silver nanoclusters: A review of structures, properties, and biosensing applications. Coord Chem Rev. 2023 Sep 15;491:215247.

30. Luo GG, Pan ZH, Han BL, Dong GL, Deng CL, Azam M, et al. Total Structure, Electronic Structure and Catalytic Hydrogenation Activity of Metal‐Deficient Chiral Polyhydride Cu57 Nanoclusters. Angewandte Chemie. 2023 Sep 11;135(37):e202306849.

31. Xu C, Jin Y, Fang H, Zheng H, Carozza JC, Pan Y, et al. A High-nuclearity copper sulfide nanocluster [S-Cu50] featuring a double-shell structure configuration with Cu (II)/Cu (I) valences. J Am Chem Soc. 2023 Oct 27;145(47):25673-85.

32. Liu X, Tang Y, Chen L, Wang L, Liu Y, Tang Z. Atomically precise Au15Ag23 nanoclusters co-protected by alkynyl and bromine: Structure analysis and electrocatalytic application toward overall water splitting. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024 Jan 31;53:300-7.

33. Wei X, Lv Y, Shen H, Li H, Kang X, Yu H, et al. Secondary ligand engineering of nanoclusters: Effects on molecular structures, supramolecular aggregates, and optical properties. Aggregate. 2023 Feb;4(1):e246.

34. Luo XM, Li YK, Dong XY, Zang SQ. Platonic and Archimedean solids in discrete metal-containing clusters. Chem Soc Rev. 2023;52(1):383-444.

35. Yan J, Malola S, Hu C, Peng J, Dittrich B, Teo BK, et al. Co-crystallization of atomically precise metal nanoparticles driven by magic atomic and electronic shells. Nat Commun. 2018 Aug 22;9(1):3357.

36. Mednikov EG, Jewell MC, Dahl LF. Nanosized (μ12-Pt) Pd164-x Pt x (CO) 72 (PPh3) 20 (x≈ 7) Containing Pt-Centered Four-Shell 165-Atom Pd− Pt Core with Unprecedented Intershell Bridging Carbonyl Ligands: Comparative Analysis of Icosahedral Shell-Growth Patterns with Geometrically Related Pd145 (CO) x (PEt3) 30 (x≈ 60) Containing Capped Three-Shell Pd145 Core. J Am Chem Soc. 2007 Sep 19;129(37):11619-30.

37. Wang Z, Wang Y, Zhang C, Zhu YJ, Song KP, Aikens CM, et al. Silvery fullerene in Ag102 nanosaucer. Natl Sci Rev. 2024 Jul;11(7):nwae192.

38. Ma MX, Ma XL, Liang GM, Shen XT, Ni QL, Gui LC, et al. A nanocluster [Ag307Cl62 (SPhtBu) 110]: chloride intercalation, specific electronic state, and superstability. J Am Chem Soc. 2021 Aug 19;143(34):13731-7.

39. Stegmaier S, Fässler TF. A bronze matryoshka: the discrete intermetalloid cluster [Sn@ Cu12@ Sn20] 12–in the ternary phases A12Cu12Sn21 (A= Na, K). J Am Chem Soc. 2011 Dec 14;133(49):19758-68.

40. Moses MJ, Fettinger JC, Eichhorn BW. Interpenetrating As20 Fullerene and Ni12 Icosahedra in the Onion-Skin [As@ Ni12@ As20] 3 Ion. Science. 2003 May 2;300(5620):778-80.

41. Bai J, Virovets AV, Scheer M. Synthesis of inorganic fullerene-like molecules. Science. 2003 May 2;300(5620):781-3.

42. Sigmon GE, Unruh DK, Ling J, Weaver B, Ward M, Pressprich L, et al. Symmetry versus minimal pentagonal adjacencies in uranium‐based polyoxometalate fullerene topologies. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009 Mar 30;48(15):2737-40.

43. Shu CC, Szczepanik DW, Muñoz-Castro A, Solà M, Sun ZM. [K2 (Bi@ Pd12@ Bi20)] 4–: An Endohedral Inorganic Fullerene with Spherical Aromaticity. J Am Chem Soc. 2024 May 8;146(20):14166-73.

44. Tang L, Wang S. Accelerating metal nanocluster synthesis: A high-throughput approach with machine learning assistance. Cell Signal. 2024;2(1):108-12.

45. Ling J, Qiu J, Burns PC. Uranyl peroxide oxalate cage and core–shell clusters containing 50 and 120 uranyl ions. Inorg Chem. 2012 Feb 20;51(4):2403-8.

46. Johansson MP, Sundholm D, Vaara J. Au32: a 24-carat golden fullerene. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004 May 10;43(20):2678-81.

47. Yuan SF, Xu CQ, Li J, Wang QM. A Ligand‐Protected Golden Fullerene: The Dipyridylamido Au328+ Nanocluster. Angewandte Chemie. 2019 Apr 23;131(18):5967-70.

48. Kenzler S, Fetzer F, Schrenk C, Pollard N, Frojd AR, Clayborne AZ, et al. Synthesis and Characterization of Three Multi‐Shell Metalloid Gold Clusters Au32 (R3P) 12Cl8. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2019 Apr 23;58(18):5902-5.

49. Xu YH, Tian WJ, Muñoz-Castro A, Frenking G, Sun ZM. An all-metal fullerene:[K@ Au12Sb20] 5−. Science. 2023 Nov 17;382(6672):840-3.

50. Wang Y, Moses-DeBusk M, Stevens L, Hu J, Zavalij P, Bowen K, et al. Sb@ Ni12@ Sb20–/+ and Sb@ Pd12@ Sb20 n cluster anions, where n=+ 1,− 1,− 3,− 4: multi-oxidation-state clusters of interpenetrating platonic solids. J Am Chem Soc. 2017 Jan 18;139(2):619-22.

51. Tang L, Dong W, Han Q, Wang B, Wu Z, Wang S. Structure and optical properties of an Ag135Cu60 nanocluster incorporating an Ag135 buckminsterfullerene-like topology. Nat Synth. 2025 Jan 14:1-8.

52. Zeng L, Zhou M, Jin R. Evolution of Excited‐State Behaviors of Gold Complexes, Nanoclusters and Nanoparticles. Chemphyschem. 2024 Jul 2;25(13):e202300687.