Abstract

Background: Bladder cancer is the most common malignancy involving the urinary system and the tenth most common malignancy worldwide. Bladder cancer is the fourth most common cancer and the fifth most leading cause of cancer death in Egypt. This study aimed to assess all patients’ molecular subtypes (basal & luminal) of muscle-invasive bladder cancer and its impact on response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and survival.

Methods: This retrospective study was carried out on 70 patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) stage II and III for two years.

Results: There were no statistically significant differences between the three studied groups regarding the type of pathology. Most of the patients were urothelial carcinoma. There was a significant difference regarding grading. There were statistically significant differences between the three groups regarding T tumor size. There were no statistically significant differences between the three studied groups regarding N lymph nodes & staging, multiplicity & site of the tumor, response to NAC. Regarding the response to CCRTh, there were significant statistically differences between the three studied groups. There was a significant increase in response in luminal subtype & non-basal-non-luminal compared with basal subtype, which showed a worse response.

Conclusions: Different molecular subtypes are established in bladder cancers that have distinct sensitivity to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy is a significant issue in managing muscle-invasive bladder cancers (MIBC). However, the association between pathologic response to NAC and molecular subtypes is not strong enough to warrant exemption from chemotherapy.

Keywords

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer, Molecular subtypes, Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Abbreviations

MIBC: Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer; NAC: N-Acetylcysteine; CCRTh: Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy; FOXA1: Forkhead Box A1; PTV: Planning Target Volume; GTV: Gross Tumor Volume; CTV: Clinical Target Volume; CR: Complete Response; PR: Partial Response; PD: Progressive Disease; SD: Stable Disease; GU: Genomically Unstable; Sccl: Squamous cell cancer like subtype

Introduction

Bladder cancer is a global public health problem [1]. According to the impact of cancer on mortality, the quality of life of patients who have cancer and their families, and economic costs are essential and remarkable issues [2]. It is the ninth common cancer, the eleventh diagnosed cancer, and the fourteenth leading cause of death due to cancer worldwide [3].

Bladder cancer, on average, is 3 to 4 times more common in men than women. The incidence and prevalence of cancer are seen in the sixth decade of life, especially its peak in the seventh and eighth. So is it mainly a disease of the elderly [1].

Bladder cancer progresses along two distinct pathways that pose distinct challenges for clinical management [4]. Low-grade non-muscle-invasive (“superficial”) cancers, which account for 70% of tumor incidence, are not immediately life-threatening, but they have a propensity for recurrence that necessitates costly lifelong surveillance [5]. In contrast, high-grade muscle-invasive bladder cancers (MIBCs) progress rapidly to become metastatic and generate the bulk of patient mortality [6].

Radical cystectomy with perioperative cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy is the current standard of care for high-risk MIBC. Treatment selection depends heavily on clinicopathologic features, but current staging systems are woefully inaccurate and result in an unacceptably high clinical understanding rate and inadequate treatment [7].

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer could be grouped into basal and luminal subtypes reminiscent of those observed in human breast cancers [8]. Basal MIBCs were associated with shorter disease-specific and overall survival, presumably because patients with these cancers tended to have more invasive and metastatic disease at presentation. The invasive/metastatic phenotype was associated with the expression of “mesenchymal” and bladder cancer stem cell [9] biomarkers, and the tumors were enriched with sarcomatoid and squamous features [10]. The link between squamous features and aggressive behavior is consistent with other recent observations [11].

Like luminal breast cancers [12], luminal MIBCs displayed active ER/TRIM24 pathway gene expression and were enriched with FOXA1, GATA3, ERBB2, and ERBB3. Therefore, agents that target the ER and/or ErbB2 and -3 may be clinically active in luminal MIBCs. In addition, luminal MIBCs contained active PPAR gene expression and activating FGFR3 mutations, so PPARg- and FGFR-3-targeted agents may be active in this subtype. Because many luminal MIBCs responded to NAC, targeted therapies should probably be combined with conventional chemotherapy for maximum efficacy [13].

This work aimed to assess molecular subtypes (basal & luminal) of muscle-invasive bladder cancer for all patients and its impact on response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and survival (disease-free survival & overall survival).

Patients and Methods

This retrospective study was carried out at Clinical Oncology Department, Tanta University Hospitals incorporation with Pathology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University and included 70 patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) stage II III throughout the period from January 2016 to January 2019. The ethics committee approved this study of faculty of medicine, Tanta University, approval code: 32759/12/18.

Adult patient more than 18 years old, Performance status 0 to 2 according to WHO/ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) score Oken et al. [14], Patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) stage II and III. Adequate hematological tests, renal and hepatic functions were included in the study.

Patients with metastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer, Patients with comorbidity interfere with chemotherapy (renal, cardiac, or hepatic insufficiency), Mental illness or dementia that interfere with patients understanding and sign of consent, and patients who underwent radical cystectomy second malignancy other than bladder carcinoma were excluded.

Seventy patients with non-metastatic MIBC stage II&III were enrolled in the study, which were subdivided into three groups according to the immunohistochemical study of two markers (ck5/6 & ck20): Group A: 32 patients with Basal subtype in which (ck5/6+ & ck20-). Group B: 24 patients with Luminal subtype in which (ck20+ & ck5/6). Group C:14 patients with Non-basal non-luminal subtype in which both markers are negative (ck5/6- & ck20-) or positive (ck5/6+ & ck20+).

The medical files are revised for: Personal data: name, age, sex, occupation, and particular habits as smoking. History: symptoms of the disease as hematuria, dysuria, frequency, urgency, and abdominal pain. Physical examination: general examination, local pelvis examination, digital rectal examination, body surface area, and weight measurement. Performance status according to ECOG performance scale Oken et al. [14]. Investigations: Laboratory as complete blood count, alkaline phosphatase, renal functions, liver functions, urine analysis, urine culture& cytology 24h creatinine clearance, and serum levels of magnesium and calcium. Radiological as CT and\or MRI abdomen and pelvis, chest X-ray or CT chest, Bone scan. Surgical and pathological as Cystoscopic evaluation by the urologist including examination under anesthesia, TURBT as complete as possible and multiple punch biopsies to detect the size and site of the tumor then this biopsies used for pathological examination & immunohistochemistry. Immunohistochemistry: For cytokerato protein (CK5\6, CK20) expression in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor tissue from muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) through transurethral resection biopsy (TURB) and is classified into Basal (CK5\6+ & CK20 -) and Luminal (CK20+ & CK5/6 -) subtypes & Non-basal-non-luminal either both markers negative or positive. The stage of the disease was determined according to AJCC staging 2017 [15].

Technique: An Iglesias resectoscope was used, allowing the surgeon to control both the inflow and outflow, which, when adjusted to proper equilibrium, maintained constant bladder volume (keeping the tumor in a fixed position) and clear vision even in bloody fields (TURBT procedure) Figure 1.

Figure 1: TURBT Procedure.

Chemotherapy (NAC) (n=53 patients): Platinum-based chemotherapy 3 cycles cisplatin, Gemzar D1, D8 & D15 Gemictabine 1000 mg/m2 iv over 30 minutes D2 cisplatin 70 mg/m2 iv over 2hrs with good hydration repeat every 4 weeks. Systemic therapy was given for 53 patients for downstaging followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Concurrent Chemotherapy (n=48 patients). Weekly Cisplatin (30 mg/m2) was administered to the 48 patients concurrent with radiotherapy.

Dose of radiotherapy: Phase I 40GY in 20 fractions. Phase II 20 GY in 10 fractions. Irradiation techniques and tolerance: Forty-eight patients received 3-D conformal radiotherapy in a dose of 40Gy in 20 fractions to the whole pelvis (including the bladder, the total bladder tumor volume, the prostate and pelvic lymph nodes as planning target volume [PTV1]) within 4 weeks (20 fraction, 2 GY, once daily, 5 days/week), with simultaneous boost limited to the bladder tumor area plus 1.5 cm margin or the whole bladder (PTV 2) with a dose of 20Gy in 10 fractions, 2 Gy/fraction, 5 days/week by high energy photons from a linear accelerator to ensure a homogeneous dose distribution.

CT simulation: For simulation, the bladder was drained of urine and filled with 30 ml of contrast medium and 10 to 30 ml of air. The rectum had to be as empty as possible. Patients were instructed to modify their diet and consume mild laxatives to minimize rectal distention. Distended rectum might introduce a systematic error in the treatment planning process (occasionally, the enema was used) [16].

On the CT simulator, the patient was positioned supine with arms on the chest and knee support. CT simulation with at least 3 mm axial slice was obtained from the mid-abdomen to the mid femur.

Target volumes: CT data were transferred to the computer treatment planning system. We contoured: Phase (1): GTV = pre-TURBT tumor volume (as assessed on cystoscopy with bladder mapping, CT, or MRI) at each slice. CTV = GTV + entire bladder + prostate and prostatic urethra (in men) or proximal 2 cm of the female urethra + regional lymphatics (internal iliac, external iliac, and obturators & presacral). PTV = CTV + margin 1 cm for bladder, 0.7cm for prostate and lymph nodes. Gross tumor volume (GTV): gross palpable or visible/demonstrable extent and location of malignant growth. Clinical target volume (CTV): Volume containing the GTV and/or a subclinical microscopic malignant disease that must be eliminated. Planning target volume (PTV): geometrical concept. It was defined to select appropriate beam sizes and arrangements, considering the net effect of all the possible geometrical variations and inaccuracies to ensure that the prescribed dose is absorbed in the CTV. Its size and shape not only depend on the CTV but also on the treatment technique used to compensate for the effects of organ and patient movement and inaccuracies in beam and patient setup. Lymph nodes: start contouring at the level of L5/S1. Internal iliac: contour inferiorly to the superior border of the head of the femur. External iliac: contour inferiorly to the level of the top of the femoral heads bilaterally. Presacral: contour between S1 and S3. Obturator: contour between the levels of the femoral heads superiorly to the superior-most portion of the symphysis pubis inferiorly.

Phase 2 (Boost): CTV boost = GTV + 0.5 cm. If GTV not well defined or lack of bladder mapping, the entire bladder (empty) is CTV. PTV boost = CTV boost + 1cm. Organs at risk: rectum, bowel bag, and bilateral femoral heads. Bowel: contour potential small bowel space within proximity to the PTV (2cm above & 2cm below). Rectum: begin contouring inferiorly at the level of the anal verge (ischial tuberosities) to the level of the sacral promontory superiorly. Femoral head: contour the left and right separately, beginning at the top of the femoral head superiorly and extending inferiorly to the level of the neck of the femur. Immunohistochemistry for basal and luminal subtypes of muscle-invasive bladder cancer; Tissue sampling: Blocks obtained from cystoscopic transurethral resection biopsy from 70 patients.

Confidentiality of the data: The prepared paraffin blocks were signed with code numbers instead of the patient’s name to maintain participants’ privacy and confidentiality of the data. Also, the results of the research were used only for scientific aims.

Preparation of cases: Specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin wax. Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were prepared for Routine hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining. Immunohistochemical staining using CK5/6 and CK20 antibodies.

Sections 3-5 µm in thickness were obtained from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded blocks, and they were subjected to ordinary H&E staining. Immunohistochemical staining procedures: Immunohistochemical study was performed in bladder carcinoma cases to detect the immunohistochemical CK5/6 and CK20 proteins expression in the studied cases. Antibodies used: I-CK5/6 is a mouse monoclonal antibody with a predicted molecular weight of 58kDa/56kDa. (Kit no. ab17133, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA, dilution 1/25-1/50). Isotype: IgG. Cellular localization: cytoplasmic. II- CK20 is a rabbit monoclonal antibody with a predicted molecular weight of 3.10 X 10 -11 M kDa. (Kit no. ab76126, DAKO, Egypt, dilution 1/100-1/250). Isotype: IgG (clonal NO EPR1622Y), Cellular localization: cytoplasmic. Methodology for immunohistochemical staining [17]: Sections (5 um) were cut from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded blocks on positively charged slides (Superfrost plus- Biogenix). They were dewaxed in a fresh xylene bath and were incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes. This step was repeated twice. Excess liquid was drained, and the slides were placed in a fresh absolute ethyl alcohol bath for three minutes at room temperature. This step was also repeated twice. Excess fluids were drained, and the slides were placed in a fresh 95% ethyl alcohol bath for three minutes at room temperature and repeated twice. Slides were rinsed in distilled water for one minute. Excess liquid was removed by sharply tapping the edge of each slide on paper toweling.

For antigen retrieval: Slides were put in a slide rack and placed in a coplan jar containing 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6). Coplan jar is placed in a water bath to keep a humid atmosphere inside the microwave oven. Slides were microwaved in a microwave oven (General Electric,1000 Watts) at power 650 for 15 minutes. The amount of fluid in the coplan jar was checked, and water was added if necessary to prevent slides from drying out. The jar was removed from the oven and allowed to cool for 20 minutes. Slides were then washed in distilled water several times then placed in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) for 5 minutes.

Blocking endogenous peroxidase: Sections were immersed in 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 30 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase activity at room temperature in a humidity chamber. Excess reagent is tapped off. Slides were then washed by PBS for 5 minutes. After washing, the slides were dried around the tissue section without drying the section itself. Blocking nonspecific staining: Two to three drops of nonspecific blocking reagent (normal goat serum) were placed on each slide to cover the tissue sections. The slides were incubated for ten minutes at room temperature in the humidity chamber. The excess reagent was tapped off.

Exposure to primary antibody: Two to three drops of the primary antibody (Ck5/6, Ck20) were placed on each slide, with an overnight incubation at room temperature in a humidity chamber. The excess reagent was tapped off, and the slides were washed for 5 minutes in PBS. Then the slides were dried around the tissue sections without drying the sections themselves.

Exposure to secondary biotinylated antibody: Two to three drops of the secondary biotinylated antibody were placed on the slides according to the manufacturer’s instructions so that the tissue sections were covered completely. The slides were incubated in the humidity chamber at room temperature for 30 minutes. The excess reagent was tapped off, and the slides were washed for 5 minutes in PBS, then the slides were dried.

Exposure to streptavidin enzyme label: Two to three drops of streptavidin enzyme label were applied. The slides were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature in the humidity chamber. The excess reagent was tapped off, and the slides were washed for 5 minutes in PBS.

Preparation of working color reagent: Diamino-Benzidine (DAB) chromogen was prepared by adding one drop of DAB chromogen per 1ml of the buffered substrate using the provided graduated test tube to measure the amount of buffered substrate needed. The components were mixed well. Color development: Several drops of the working color reagent were placed on each slide using the provided transfer pipette. The slides were incubated for 5-10 minutes at room temperature in the humidity of the chamber. The slides were washed with Tap water. Counter-stain with hematoxylin for one minute was done, then the slides were washed in distilled water. Sections were dehydrated in alcohol, put in xylene then mounted in DPX. Interpretation of immunohistochemical staining: Interpretation of CK5/6 & CK20 immunostaining: All immunohistochemical stains were scored using a semiquantitative immunoreactive score (IRS), quantifying staining intensity 0 (no staining reaction), 1+ (weak staining reaction), 2+ (moderate staining reaction), 3+ (strong staining reaction)) and percentage of positively stained cells 0 (0%), 1 (<10%), 2 (10–50%), 3 (51–80%), 4 (>80%)) resulting in IRS values ranging from 0 to 12 [18]. A positive status was defined as an IRS >1 for CK5/6 and an IRS >6 for CK20. Exclusive positivity for CK5/6 (CK20-/ CK5/6+) in the basal-like subtype of bladder cancer. Exclusive positivity for CK20 (CK20+/CK5/6-) in the luminal subtype of bladder cancer. Both markers are positive (ck20+/ck5/6+), or both markers are negative (ck20- /ck5/6- ), neither basal nor luminal.

Assessment of Tumor response: A tumor response assessment was performed after neoadjuvant chemotherapy & concurrent chemoradiotherapy according to RECIST criteria version 1.1 [19]. Tumor response was assessed by CT scan and MRI for all patients one week after the last cycle of chemotherapy & 4 weeks after the end of CCRTH to evaluate the radiological response. Cystoscopy and biopsy were performed for patients who achieved a complete radiological response to confirm the pathological response.

RECIST criteria: A complete clinical response (CR): This was defined as the complete disappearance of the intravesical lesion and normalization of the computed tomography findings. Pathological complete response is confirmed by cystoscopic biopsy in case of complete clinical response. A partial response (PR): Was defined as a 50% decrease in the sum of the products of two perpendicular diameters of all measurable lesions for a minimum of 4 weeks with no increase of 25% in the size of any single lesion. Progressive disease (PD): If any new lesion appeared, if the tumor size increased 25% greater than the pretreatment measurements, or in the case of deterioration in clinical status consistent with disease progression. Stable disease (SD): Patients whose findings did not meet the criteria of CR, PR, or PD and who could be followed for at least 2 months were classified as having stable disease. The overall response rate included complete and partial responses, while the disease control rates included complete, partial, and stable disease.

Follow-up and restaging: Patients were followed up at 3-month intervals for the first 3 years. Evaluations consisted of medical history, physical examination, and cystoscopy, with biopsies only if clinically indicated. Routine investigations during follow-up included hematologic studies, biochemical profiles, and pelviabdominal u/s. Each year, abdominopelvic computed tomography, chest X-ray, bone scan, or other instrumental examination were performed if symptoms suspicious for metastasis appeared.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were organized, tabulated, and statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS software package version 20.0. (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) Qualitative data were described using numbers and percentages. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to verify the normality of distribution. Quantitative data were described using range (minimum and maximum), mean, standard deviation. The significance of the obtained results was judged at the 5% level. The used tests were: Chi-square test for categorical variables, to compare between different groups. Monte Carlo correction for chi-square when more than 20% of the cells have an expected count less than 5. F-test (ANOVA) for normally distributed quantitative variables to compare between more than two groups. Kaplan-Meier: Survival curve was used for the significant relation with disease-free survival and overall survival.

Results

There were no statistically significant differences between the three groups regarding patient characteristics (Table 1). There were no statistically significant differences between the three studied groups regarding the type of pathology. Most of the patients were urothelial carcinoma 65 (92.9%), 3 (4.3%) were squamous cell carcinoma, and 2 (2.9%) were adenocarcinoma. Regarding grading, there were statistically significant differences between the three studied groups most of the patients were high grade45 (64.3% of cases), 25 (78.1% of cases) in basal subtypes were high grade, 10 (41.7% of cases) in luminal subtypes were high grade & 10 (71.4% of cases) in non-luminal non-basal subtypes were high grade (Table 2).

|

Patient characteristic |

Total sample |

Molecular subtypes |

Test of Sig. |

p |

|||||

|

(A) Basal |

(B) Luminal |

(C) Non-basal-non-luminal (n=14) |

|||||||

|

Total |

Both negative |

Both positive |

|||||||

|

No % |

No % |

No % |

No % |

No % |

No % |

||||

|

Gender |

|

||||||||

|

Male |

50 (71.4%) |

23 (71.9%) |

16 (66.7%) |

11 (78.6%) |

6 (100%) |

5 (62.5%) |

χ2= |

MCp= |

|

|

Female |

20 (28.6%) |

9 (28.1%) |

8 (33.3%) |

3 (21.4%) |

0 (0%) |

3 (37.5%) |

|||

|

Age (years) |

|

||||||||

|

≤60 |

27 (38.6%) |

14 (43.8%) |

6 (25.0%) |

7 (50%) |

4 (66.7%) |

3 (37.5%) |

χ2= |

MCp= |

|

|

>60 |

43 (61.4%) |

18 (56.3%) |

18 (75.0%) |

7 (50%) |

2 (33.3%) |

5 (62.5%) |

|||

|

Min-Max |

43 - 65 |

43 - 65 |

50 - 65 |

52 - 63 |

52 - 63 |

52 - 63 |

F= |

0.528 |

|

|

Mean ± SD |

60.34 ± 3.69 |

60.09 ± 4.20 |

61.17 ± 3.19 |

59.50 ± 3.18 |

59.0 ± 3.79 |

59.88 ± 2.85 |

|||

|

Performance status |

|

||||||||

|

0 |

11 (15.7%) |

7 (21.9%) |

1 (4.2%) |

3 (21.4%) |

1 (16.7%) |

2 (25.0%) |

χ2= |

MCp= |

|

|

1 |

42 (60.0%) |

19 (59.4%) |

14 (58.3%) |

9 (64.3%) |

3 (50.0%) |

6 (75.0%) |

|||

|

2 |

17 (24.3%) |

6 (18.8%) |

9 (37.5%) |

2 (14.3%) |

2 (33.3%) |

0 (0%) |

|||

|

Smoking |

|

||||||||

|

No |

28 (40.0%) |

15 (46.9%) |

9 (37.5%) |

4 (28.6%) |

1 (16.7%) |

3 (37.5%) |

χ2= |

MCp= |

|

|

Yes |

42 (60.0%) |

17 (53.1%) |

15 (62.5%) |

10 (71.4%) |

5 (83.3%) |

5 (62.5%) |

|||

|

P: p value for comparing between molecular subtypes |

|||||||||

|

|

Total sample |

Molecular subtypes |

χ2 |

MCp |

||||||||||||

|

(A) Basal |

(B) Luminal |

(C) Non-basal-non-luminal (n=14) |

||||||||||||||

|

Total |

Both negative |

Both positive |

||||||||||||||

|

|

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

||||

|

Histopathology |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Adenocarcinoma |

2 |

2.9 |

1 |

3.1 |

1 |

4.2 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

2.779 |

0.929 |

||

|

Squamous cell carcinoma |

3 |

4.3 |

1 |

3.1 |

2 |

8.3 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

||||

|

Urothelial carcinoma |

65 |

92.9 |

30 |

93.8 |

21 |

87.5 |

14 |

100.0 |

6 |

100.0 |

8 |

100.0 |

||||

|

Variant histology in specimen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

No |

35 |

50.0 |

13 |

40.6 |

14 |

58.3 |

8 |

57.1 |

5 |

83.3 |

3 |

37.5 |

29.021* |

0.001* |

||

|

Papillary |

13 |

18.6 |

3 |

9.4 |

10 |

41.7 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

||||

|

Sarcomatoid |

4 |

5.7 |

3 |

9.4 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

7.1 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

12.5 |

||||

|

Squamatoid |

17 |

24.3 |

12 |

37.5 |

0 |

0.0 |

5 |

35.7 |

1 |

16.7 |

4 |

50.0 |

||||

|

Sarcomatoid & Squamatoid |

1 |

1.4 |

1 |

3.1 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

||||

|

Sig. bet. grps |

|

MCP1<0.001*, MCP2=0.855, MCP3<0.001* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Grading |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Low |

9 |

12.9 |

1 |

3.1 |

7 |

29.2 |

1 |

7.1 |

1 |

16.7 |

0 |

0.0 |

12.472* |

0.028* |

||

|

Moderate |

16 |

22.9 |

6 |

18.8 |

7 |

29.2 |

3 |

21.4 |

2 |

33.3 |

1 |

12.5 |

||||

|

High grade |

45 |

64.3 |

25 |

78.1 |

10 |

41.7 |

10 |

71.4 |

3 |

50.0 |

7 |

87.5 |

||||

|

Sig. bet. grps |

|

MCp1=0.007*, MCp2=0.855,MCp3=0.142 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

P: p value for comparing between molecular subtypes, p1: p value for comparing between Basal and Luminal, p2: p value for comparing between Basal and Non-basal-non-luminal, p3: p value for comparing between Luminal and Non-basal-non-luminal, *: Statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05 |

||||||||||||||||

Regarding T tumor size, there were statistically significant differences between three studied groups 15 (46.9% of cases) in basal subtype were T3b, 13 ( 54.2% of cases) in luminal subtypes were T2b and 5 (35.7% of cases) in Non-basal-non-luminal were T2b & 5 ( 35.7% of cases) were T3b. Regarding N lymph nodes, there were no statistically significant differences between the three studied groups 14 (43.8% of cases) were N1 in basal subtype, 15 (62.5% of cases) were N0 in luminal subtype While, 28.6% of cases in non-basal-non-luminal were N0 & 28.6% of cases were N2. Regarding staging, 18 (56.3% of cases) were IIIa in basal subtype, 11 (45.8% of cases) were II in luminal subtype, while 8 (57.1% of cases) in non-basal-non-luminal subtype were IIIa (Table 3).

|

|

Total sample |

Molecular subtypes |

χ2 |

MCp |

|||||||||||

|

(A) Basal |

(B) Luminal |

(C) Non-basal-non-luminal (n = 14) |

|||||||||||||

|

Total |

Both negative (n=6) |

Both positive |

|||||||||||||

|

|

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

|

||

|

Tumor size |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

T2a |

5 |

7.1 |

1 |

3.1 |

4 |

16.7 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

21.863* |

0.012* |

|

|

T2b |

25 |

35.7 |

7 |

21.9 |

13 |

54.2 |

5 |

35.7 |

3 |

50.0 |

2 |

25.0 |

|

||

|

T3a |

1 |

1.4 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

7.1 |

1 |

16.7 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

||

|

T3b |

26 |

37.1 |

15 |

46.9 |

6 |

25.0 |

5 |

35.7 |

2 |

33.3 |

3 |

37.5 |

|

||

|

T4a |

13 |

18.6 |

9 |

28.1 |

1 |

4.2 |

3 |

21.4 |

0 |

0.0 |

3 |

37.5 |

|

||

|

Sig. bet. grps |

|

MCp1=0.003*,MCp2=0.522,MCp3=0.097 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Lymph nodes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

N0 |

28 |

40.0 |

9 |

28.1 |

15 |

62.5 |

4 |

28.6 |

3 |

50.0 |

1 |

12.5 |

13.090 |

0.096 |

|

|

N1 |

23 |

32.9 |

14 |

43.8 |

4 |

16.7 |

5 |

35.7 |

2 |

33.3 |

3 |

37.5 |

|

||

|

N2 |

15 |

21.4 |

8 |

25.0 |

3 |

12.5 |

4 |

28.6 |

1 |

16.7 |

3 |

37.5 |

|

||

|

N3 |

4 |

5.7 |

1 |

3.1 |

2 |

8.3 |

1 |

7.1 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

12.5 |

|

||

|

Metastases |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

M0 |

70 |

100.0 |

32 |

100.0 |

24 |

100.0 |

14 |

100.0 |

6 |

100.0 |

8 |

100.0 |

– |

– |

|

|

Stage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

II |

17 |

24.3 |

5 |

15.6 |

11 |

45.8 |

1 |

7.1 |

1 |

16.7 |

0 |

0.0 |

10.564 |

0.077 |

|

|

IIIa |

34 |

48.6 |

18 |

56.3 |

8 |

33.3 |

8 |

57.1 |

4 |

66.7 |

4 |

50.0 |

|

||

|

IIIB |

19 |

27.1 |

9 |

28.1 |

5 |

20.8 |

5 |

35.7 |

1 |

16.7 |

4 |

50.0 |

|

||

|

P: p value for comparing between molecular subtypes, p1: p value for comparing between Basal and Luminal p2: p value for comparing between Basal and Non-basal-non-luminal, p3: p value for comparing between Luminal and Non-basal-non-luminal, *: Statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05 |

|

||||||||||||||

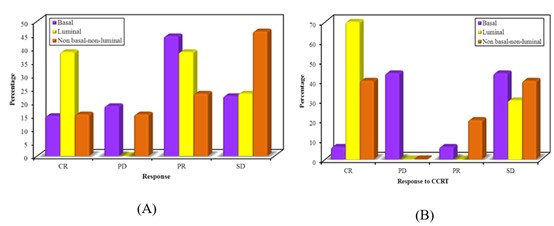

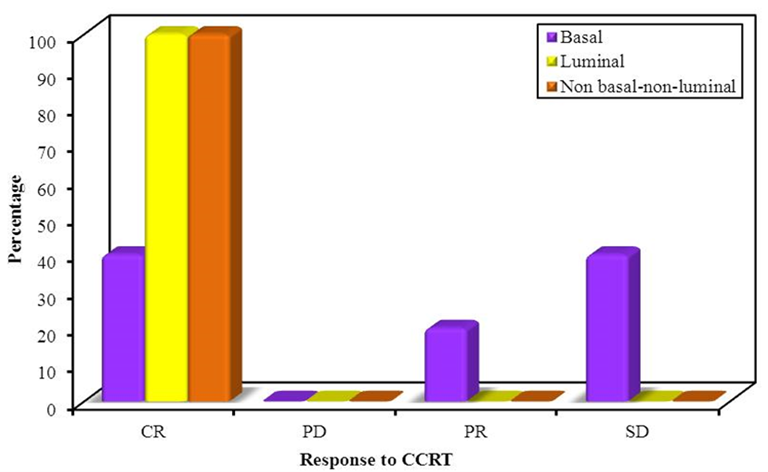

There were no statistically significant differences between the three studied groups regarding response to NAC. In the basal subtype, 16 (59.2% of cases) showed response to NAC. In the luminal subtype, 10 (77% of cases) showed a response. In non-basal-non-luminal subtype 5 (38.5% of cases) showed response. Figure 2 (B) showed response to CCRT for 31 patients After NAC. There was a statistically significant difference between the three studied groups 12 (38.8% of cases) responded to CCRT. In the basal subtype, 2 (12.6 % of patients) showed response to CCRT. In luminal subtype 7 (70% of patients) showed response to CCRT. In non-basal-non-luminal subtype 3 (60% of patients) showed response to CCRT (Figure 2).

Figure 2: (A) Showing response to NAC, (B) Comparison between molecular subtypes according to response to CCRT (n=31).

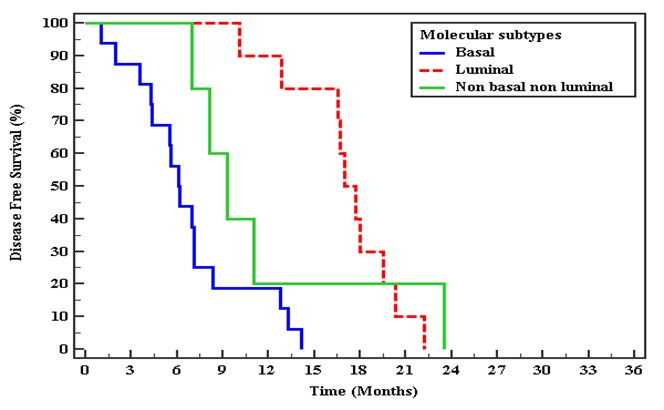

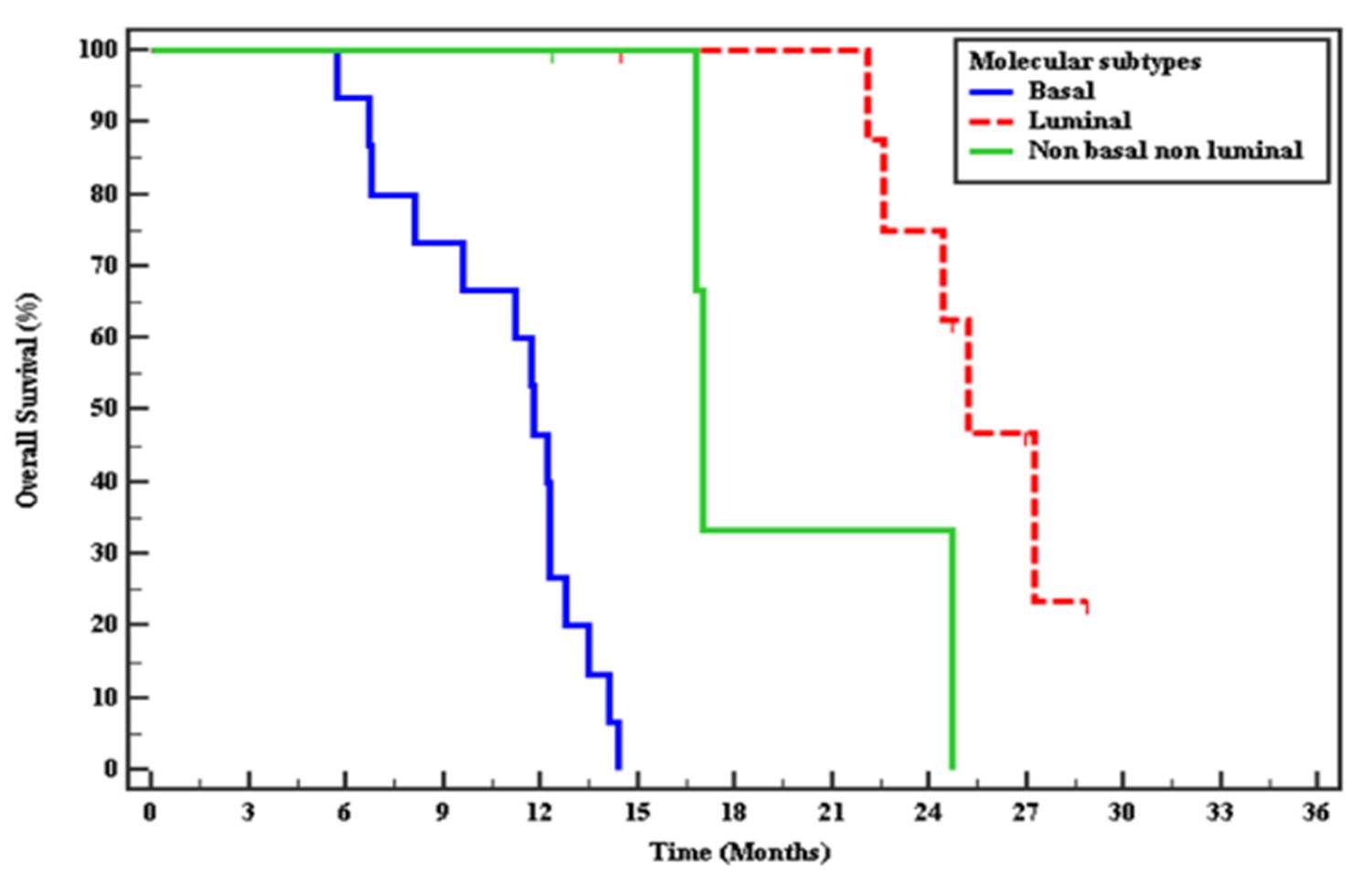

There was a statistically significant difference between the three studied groups median of DFS in basal subtype 6.77 months, in luminal subtype mean of DFS 17.08 months. In non-basal-non-luminal mean of DFS 11.79 months. There was a statistically significant difference between the three studied groups median of OS in basal subtype 11.17 months, luminal subtype 25.9 months & the non-basal-non-luminal mean of OS 20.8 months (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 3: Kaplan-Meier curve for Disease-free survival with Molecular subtypes for response to CCRT.

Figure 4: Kaplan-Meier curve for Overall survival with Molecular subtypes for response to CCRT.

There was no statistically significant difference between the three studied groups regarding T, N & staging (Table 4). Regarding multiplicity, there was a statistically significant difference between the three studied groups. 17 (77.3% of cases) had multiple foci of the tumor. In the basal subtype, 100% of cases had multiple foci. In the luminal subtype, 2 (66.7% of cases) had multiple foci. In non-basal-non-luminal 4 (50% of cases) had single focus & 4 (50%) had multiple foci. Regarding the site of the tumor, there was no statistically significant difference between the three studied groups. 12 (54.6% of cases) tumors were at the bladder’s lateral wall (Table 5).

|

|

Total sample |

Molecular subtypes |

χ2 |

MCp |

||||||||||

|

(A) Basal |

(B) Luminal |

(C) Non-basal-non-luminal (n = 8) |

||||||||||||

|

Total |

Both negative |

Both positive |

||||||||||||

|

|

No |

% |

No |

% |

No |

% |

No |

% |

No |

% |

No |

% |

||

|

Tumor size |

|

|||||||||||||

|

T2a |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

4.996 |

0.645 |

|

T2b |

4 |

18.2 |

1 |

9.1 |

1 |

33.3 |

2 |

25.0 |

1 |

100.0 |

1 |

14.3 |

||

|

T3a |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

||

|

T3b |

10 |

45.5 |

6 |

54.5 |

1 |

33.3 |

3 |

37.5 |

0 |

0.0 |

3 |

42.9 |

||

|

T4a |

8 |

36.4 |

4 |

36.4 |

1 |

33.3 |

3 |

37.5 |

0 |

0.0 |

3 |

42.9 |

||

|

Lymph nodes |

|

|||||||||||||

|

N0 |

2 |

9.1 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

33.3 |

1 |

12.5 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

14.3 |

7.790 |

0.774 |

|

N1 |

8 |

36.4 |

4 |

36.4 |

1 |

33.3 |

3 |

37.5 |

1 |

100.0 |

2 |

28.6 |

||

|

N2 |

10 |

45.5 |

6 |

54.5 |

1 |

33.3 |

3 |

37.5 |

0 |

0.0 |

3 |

42.9 |

||

|

N3 |

2 |

9.1 |

1 |

9.1 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

12.5 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

14.3 |

||

|

Metastases |

|

|||||||||||||

|

M0 |

22 |

100.0 |

11 |

100.0 |

3 |

100.0 |

8 |

100.0 |

1 |

100.0 |

7 |

100.0 |

– |

– |

|

Stage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

II |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

2.172 |

0.702 |

|

IIIa |

10 |

45.5 |

4 |

36.4 |

2 |

66.7 |

4 |

50.0 |

1 |

100.0 |

3 |

42.9 |

||

|

IIIB |

12 |

54.5 |

7 |

63.6 |

1 |

33.3 |

4 |

50.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

4 |

57.1 |

||

|

P: p value for comparing between molecular subtypes |

||||||||||||||

|

|

Total sample |

Molecular subtypes |

χ2 |

MCp |

||||||||||||

|

(A) Basal |

(B) Luminal |

(C) Non-basal-non-luminal (n = 8) |

||||||||||||||

|

Total |

Both negative |

Both positive |

||||||||||||||

|

|

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

||||

|

Multiplicity |

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Single focus |

5 |

22.7 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

33.3 |

4 |

50.0 |

1 |

100.0 |

3 |

42.9 |

8.403* |

0.025* |

||

|

Multiple foci |

17 |

77.3 |

11 |

100.0 |

2 |

66.7 |

4 |

50.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

4 |

57.1 |

||||

|

Sig. bet. grps. |

|

|

FEp1=0.214, FEp2=0.018*, FEp3=1.000 |

|

||||||||||||

|

Site of tumor |

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Right lateral wall |

6 |

27.3 |

4 |

36.4 |

1 |

33.3 |

1 |

12.5 |

1 |

100.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

5.633 |

0.085 |

||

|

Left lateral wall |

6 |

27.3 |

2 |

18.2 |

2 |

66.7 |

2 |

25.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

2 |

28.6 |

3.127 |

0.518 |

||

|

Trigone |

2 |

9.1 |

2 |

18.2 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

2.485 |

0.670 |

||

|

Dome |

8 |

36.4 |

4 |

36.4 |

0 |

0.0 |

4 |

50.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

4 |

57.1 |

3.168 |

0.455 |

||

|

Posterior wall |

7 |

31.8 |

4 |

36.4 |

1 |

33.3 |

2 |

25.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

2 |

28.6 |

0.928 |

1.000 |

||

|

Anterior wall |

10 |

45.5 |

6 |

54.5 |

1 |

33.3 |

3 |

37.5 |

0 |

0.0 |

3 |

42.9 |

1.499 |

1.000 |

||

|

P: p value for comparing between molecular subtypes, p1: p value for comparing between Basal and Luminal, p2: p value for comparing between Basal and Non-basal-non-luminal, p3: p value for comparing between Luminal and Non-basal-non-luminal, *: Statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05 |

||||||||||||||||

Figure 4 showed a response of 17 patients with stage II to CCRT. There were statistically significant differences between the three studied groups. 82.4% of cases showed complete response. In the basal subtype, 60% showed a response. In the luminal subtype, 100% of patients showed a response. In the non-basal-non-luminal subtype, one patient who received CCRT showed CR (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Comparison between molecular subtypes according to response to CCRT for stage II (n=17).

Discussion

Radical cystectomy with perioperative cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy is the current standard of care for high-risk MIBC. Treatment depends on clinicopathologic features, but current staging systems are inaccurate and result in an unacceptably high rate of clinical understating and inadequate treatment [7]. Also, cisplatin-based chemotherapy is only effective in 30-40% of cases, and it is not yet possible to prospectively identify the patients who are likely to obtain benefits [6]. Also add, no practical alternative to cisplatin-based chemotherapy has been identified for resistant tumors. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop a more precise, biology-based approach to the classification of bladder cancer to inform clinical management.

MIBCs can be grouped into basal and luminal subtypes that resemble those observed in human breast cancers [12]. Basal MIBCs were associated with shorter disease-specific and overall survival because patients with these cancers tended to have more invasive and metastatic disease at presentation. The invasive/ metastatic phenotype was associated with the expression of "mesenchymal" and bladder cancer stem cell [9] biomarkers, and the tumors were enriched with sarcomatoid and squamous features [10].

In this study, regarding grading, there were statistically significant differences between the three studied groups. Most of the patients were high grade 45 (64.3% of cases), 25 (78.1%) of cases in basal subtypes were high grade, 10 ( 41.7%) of cases in luminal subtypes were high grade while 10 (71.4%) of cases in non-luminal non-basal subtypes were high grade comparable with Sikic et al. [20] in which (67.2%) of cases were high grade, 68.7% of cases in basal subtype were high grade, 55.6% of cases in luminal subtype were high grade while 62.5% of cases in non-luminal non-basal subtype were moderate grade.

In this study, Regarding T tumor size, there were statistically significant differences between the three studied groups as tumor size more advanced in basal subtype at diagnosis. 15 (46.9%) of cases in (basal subtype) were T3b, 13 (54.2%) of cases in (luminal subtypes) were T2b compared with Choi et al. [5] in which 40% of cases in basal subtype were T4, 39% of cases were T2 while 17% were T3, in luminal subtype 50% of cases were T2 while 21% were T3. In this study, 5 (35.7%) of cases in Non-basal-non-luminal were T2b & 5 (35.7%)of cases were T3b compared with Sikic et al. [20] in which 23.76 of patients in non-luminal non-basal subtype were T3 while 13.2 % of patients were T2.

In this study, regarding N lymph nodes, there were no statistically significant differences between the three studied groups 42 (60%) of cases were N+. In basal subtype, 23 (71%) of cases were N+, in luminal subtype 9 (37.5%) of cases were N+ compared with Choi et al. [5] in which 11(15%) of cases were N+. In the basal subtype, 5 (22%) cases were N+; in the luminal subtype, 5 (21%) cases were N+. In this study, 10 (71.4%) of cases in non-basal-non-luminal were N+ compared with Sikic et al. [20], in which 14.58% of patients in non-basal-non-luminal were N+. Also, in Razzaghdoust et al. there were no statistically significant differences between the three studied groups.

In this study, regarding the site of tumor most common site of tumor at the lateral wall of bladder seen in 33 patients (48.1% of patients) as Freedman et al., Daneshmand et al. and Bray et al. [21-23] reported that most common site of tumor at the lateral wall of bladder cancer.

In this study, regarding the multiplicity of tumors, there was no statistically significant difference between the three studied groups 42 (60%) of cases had a single focus while 28 (40%) of cases had multiple foci. In the basal subtype, 17 (53.1%) cases had multiple foci, while 18 (75%) cases had a single focus in the luminal subtype. In comparison, in non-basal-non-luminal subtype 9 (64.3%) of cases had a single focus compared with Tanaka et al. 2018 [24] in which divided MIBC according to molecular subtypes another classification into urobasal (Uro), genomically unstable (GU). Squamous cell cancer-like subtype (sccl) showed 48% of patients had multifocality. In urobasal, 62% of patients showed multifocality, in genomically unstable 52% showed multifocality, while in squamous cell cancer-like subtype, 29% showed multifocality.

In this study, regarding NAC, 53/70 patients (75.7% of patients) received NAC (Gemzar, Cisplatin), 27 (51%) of them were basal subtypes, 13 (24.5%) of them were luminal subtypes & 13 (24.5%) of them were non-basal-non-luminal subtype. In this study, 53/70 (75.7%) patients received NAC regarding response to NAC, no statistically significant difference between the three studied groups regarding response to NAC. Still, there was an increase in response in luminal subtype more than the other two groups do. 11 (20.8%) of patients showed CR, 20 (37.7%) of patients showed PR, 7 (13.2%) of patients showed PD, and 15 (28.3%) of patients showed SD. In the basal subtype, 16 (59.2%) of cases showed response to NAC. In the luminal subtype, 10 (77%) of patients showed response to NAC. In non-basal-non-luminal subtype 5 (38.5%) of cases showed response to NAC. In comparison with Choi et al. [5], there was a statistically significant difference between three studied groups regarding response to NAC luminal subtype better in response than basal subtype & basal subtype better in response than P53 like subtype with P-value = 0.018. In comparison with McConkey et al. [24] also showed that basal subtype showed the most significant benefit from NAC regarding OS, P53 like tumor chemoresistance. In comparison with Seiler et al. [25], which assessed NAC's effect on OS & revealed that basal subtype gets the most significant benefit from NAC, which improves OS in this group while luminal subtype had the best OS with or without NAC. In contrast, Font et al. [26] have shown that the patients with basal/squamous (BASQ)-like tumors (KRT5/6/KRT14 high; FOXA1/GATA3 low) were more likely to achieve a CR to NAC (p=0.017).

In this study, 31/53 (58%) patients from 53 received NAC showed response so received CCRT, regarding response to CCRT to 31 patients, 12 (38.8%) of patients showed response to CCRT, 2 (12.6%) of patients in basal subtype showed a response, 7 (70%) of patients in luminal subtype showed response & 3 (60%) of patients in non- basal non- luminal subtype showed a response. This means the luminal subtype showed a significantly more favorable CRT response than the non-basal non-luminal & basal subtype. No previous studies assessed response to CCRT regarding this molecular subtype's classification. The only study assessed response to CCRT according to molecular subtypes. Tanaka et al. [27] in which divided MIBC according to molecular subtypes, another classification into urobasal (Uro), genomically unstable (GU), and squamous cell cancer-like subtype (sccl). Off all patients, Clinical complete response (CR) was achieved in 42% of patients after CRT, with a significantly higher proportion in GU patients (52%) and SCCL patients (45%) than in Uro-basal patients (15%).GU and SCCL cancers showed significantly more favorable CRT responses than did Uro cancers.

Regarding DFS & OS to patients who received CCRT after NAC showed a significant increase in DFS& OS in luminal subtypes and non- basal non-luminal compared to basal subtype (P-Value=0.001) compared with Choi et al. [5] also there is a significant increase in DFS & OS in luminal subtypes compared to basal subtype. In contrast, Razzaghdoust et al. showed that the median OS was 28, 39, 55, and 34 months for patients categorized as luminal, basal, double negative, and double-positive, respectively. This means no statistically significant difference in the OS was found between the IHC-based subtypes (P=0.721) & Seiler et al. [25] demonstrated that the OS of patients with basal and luminal subtypes was not significantly different among the NAC-treated group this difference may be due to as NAC improve OS in basal subtype but not affect OS in the non- basal subtype.

In this study, regarding patients who underwent radical cystectomy 22/53(41%) patients from 53 patients who received NAC showed no response or progressive course to NAC, 11 (50%) were basal subtype, 3 (13.6%) were luminal subtype & 8 (36.3%) were non-basal non-luminal subtype. All patients were stage III. Regarding multiplicity, 77.3% of patients had multifocality, in basal subtype, 100% of patients had multifocality, in luminal subtype 66.7% of patients had multifocality, in non- basal non-luminal subtype, 50% of patients had multifocality compared with Sikic et al. [28] in which 73 patients underwent to radical cystectomy as a primary treatment without receiving adjuvant treatment 44 (60.3%) patients were stage II & 29 (39.7%) were stage III.

In this study, there were 17/70 (24%) patients from the total sample (70 patients) were stage II at diagnosis received CCRT,15 (88.3%) of patients showed response to CCRT, 3 ( 60%) in basal subtype showed a response, 11 (100%) of luminal subtype showed response & one patient (100%) of non- basal non-luminal subtype showed a response. This means the luminal subtype showed a significantly more favorable CRT response than the non-basal non-luminal & basal subtype. No previous studies assessed response to CCRT regarding this molecular subtypes classification. The only study assessed response to CCRT according to molecular subtypes. Tanaka et al. [27] in which divided MIBC according to molecular subtypes another classification into urobasal (Uro), genomically unstable (GU), and squamous cell cancer-like subtype (sccl). Off all patients, Clinical complete response (CR) was achieved in 42% of patients after CRT, with a significantly higher proportion in GU patients (52%) and SCCL patients (45%) than in Urobasal patients (15%).GU and SCCL cancers showed significantly more favorable CRT responses than did Uro basal cancers.

Regarding DFS & OS, those patients showed a significant increase in DFS & OS in luminal subtypes and non- basal non-luminal compared to basal subtype (P-Value=0.001). The mean time of progression was 10.16 months in the basal subtype, 32.8 months in the luminal subtype, and 29.27 months in non -basal non-luminal. The mean of OS in17 was 20.31 months in basal subtype, 35.69 months in luminal subtype, 35 months in non -basal non-luminal subtype compared with Choi et al. [5] significant increase in OS& DES in luminal subtype compared to basal subtype.

Conclusions

Different molecular subtypes are established in bladder cancers that have distinct clinical behavior and sensitivity to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy is a significant issue in the management of MIBC. However, the association between pathologic response to NAC and molecular subtypes is not strong enough to warrant exemption from chemotherapy. Luminal tumors generally bear a better prognosis and increased survival than basal tumor subtypes.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil

Conflict of Interest

Nil

References

2. Klotz L, Brausi MA. World Urologic Oncology Federation Bladder Cancer Prevention Program: a global initiative. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:25-9.

3. Mahdavifar N, Ghoncheh M, Pakzad R, Momenimovahed Z, Salehiniya H. Epidemiology, Incidence and Mortality of Bladder Cancer and their Relationship with the Development Index in the World. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:381-6.

4. Kamat AM, Hahn NM, Efstathiou JA, Lerner SP, Malmström PU, Choi W, et al. Bladder cancer. Lancet. 2016;388:2796-810.

5. Choi W, Porten S, Kim S, Willis D, Plimack ER, Hoffman-Censits J, et al. Identification of distinct basal and luminal subtypes of muscle-invasive bladder cancer with different sensitivities to frontline chemotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:152-65.

6. Shah JB, McConkey DJ, Dinney CP. New strategies in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: on the road to personalized medicine. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2608-12.

7. Svatek RS, Shariat SF, Novara G, Skinner EC, Fradet Y, Bastian PJ, et al. Discrepancy between clinical and pathological stage: external validation of the impact on prognosis in an international radical cystectomy cohort. BJU Int. 2011;107:898-904.

8. Finn RS, Crown JP, Lang I, Boer K, Bondarenko IM, Kulyk SO, et al. The cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib in combination with letrozole versus letrozole alone as first-line treatment of oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative, advanced breast cancer (PALOMA-1/TRIO-18): a randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:25-35.

9. Chan KS, Espinosa I, Chao M, Wong D, Ailles L, Diehn M, et al. Identification, molecular characterization, clinical prognosis, and therapeutic targeting of human bladder tumor-initiating cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14016-21.

10. Sjödahl G, Lauss M, Lövgren K, Chebil G, Gudjonsson S, Veerla S, et al. A molecular taxonomy for urothelial carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3377-86.

11. Mitra AP, Bartsch CC, Bartsch G, Jr., Miranda G, Skinner EC, Daneshmand S. Does presence of squamous and glandular differentiation in urothelial carcinoma of the bladder at cystectomy portend poor prognosis? An intensive case-control analysis. Urol Oncol. 2014;32:117-27.

12. Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747-52.

13. Hoffman KL, Lerner SP, Smith CL. Raloxifene inhibits growth of RT4 urothelial carcinoma cells via estrogen receptor-dependent induction of apoptosis and inhibition of proliferation. Horm Cancer. 2013;4:24-35.

14. Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649-55.

15. Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, et al. The eighth edition AJCC cancer staging manual: continuing to build a bridge from a population‐based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2017;67:93-9.

16. Clark PE, Agarwal N, Biagioli MC, Eisenberger MA, Greenberg RE, Herr HW, et al. Bladder cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:446-75.

17. Nieminen T, Välitalo H, Säde E, Paloranta A, Koskinen K, Björkroth J. The effect of marination on lactic acid bacteria communities in raw broiler fillet strips. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2012;3.

18. Remmele W, Stegner HE. Recommendation for uniform definition of an immunoreactive score (IRS) for immunohistochemical estrogen receptor detection (ER-ICA) in breast cancer tissue. Pathologe. 1987;8:138-40.

19. Bogaerts J, Ford R, Sargent D, Schwartz LH, Rubinstein L, Lacombe D, et al. Individual patient data analysis to assess modifications to the RECIST criteria. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:248-60.

20. Sikic D, Keck B, Wach S, Taubert H, Wullich B, Goebell PJ, et al. Immunohistochemiocal subtyping using CK20 and CK5 can identify urothelial carcinomas of the upper urinary tract with a poor prognosis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0179602.

21. Freedman ND, Silverman DT, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A, Abnet CC. Association Between Smoking and Risk of Bladder Cancer Among Men and Women. JAMA. 2011;306:737-45.

22. Daneshmand S. Epidemiology and risk factors of urothelial (transitional cell) carcinoma of the bladder. UpToDate. 2016. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-and-risk-factors-ofurothelial-transitional-cell-carcinoma-of-the-bladder; Accessed on: 06/07/2017.

23. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424.

24. McConkey DJ, Choi W, Shen Y, Lee IL, Porten S, Matin SF, et al. A Prognostic Gene Expression Signature in the Molecular Classification of Chemotherapy-naïve Urothelial Cancer is Predictive of Clinical Outcomes from Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: A Phase 2 Trial of Dose-dense Methotrexate, Vinblastine, Doxorubicin, and Cisplatin with Bevacizumab in Urothelial Cancer. Eur Urol. 2016;69:855-62.

25. Seiler R, Ashab HAD, Erho N, van Rhijn BWG, Winters B, Douglas J, et al. Impact of Molecular Subtypes in Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer on Predicting Response and Survival after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Eur Urol. 2017;72:544-54.

26. Font A, Domènech M, Benítez R, Rava M, Marqués M, Ramírez JL, et al. Immunohistochemistry-Based Taxonomical Classification of Bladder Cancer Predicts Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12.

27. Tanaka H, Yoshida S, Koga F, Toda K, Yoshimura R, Nakajima Y, et al. Impact of Immunohistochemistry-Based Subtypes in Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer on Response to Chemoradiation Therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;102:1408-16.

28. Sikic D, Eckstein M, Wirtz RM, Jarczyk J, Worst TS, Porubsky S, et al. FOXA1 Gene Expression for Defining Molecular Subtypes of Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer after Radical Cystectomy. J Clin Med. 2020;9.