Abstract

Cancer is one of the major public health problems globally which arises due to uncontrolled cellular proliferation. Tumor necrosis factor alpha is a member of the TNF/TNFR cytokine superfamily. Currently, the venom from various sources have been widely used in the treatment of cancer. The bioactive present in bee venom has been reported to have potential antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer activity which has drawn the attention to identify the novel inhibitor against TNF-α. Bee venom has been reported to target ovarian, breast, prostate and malignant hepatocellular carcinoma. TNF-α is involved in the maintenance and homeostasis of the immune system, inflammation, and host defense. The oncogenic protein TNF-α plays a critical role in the development of various cancers including renal, lung, liver, prostate, bladder, and breast cancer. TNF-α enhances cancer cell growth, proliferation, invasion, and metastasis, as well as tumor angiogenesis. Due to the high prevalence and mortality, TNF-α associated cancers have remained a significant health problem globally. TNF acts biologically by activating certain signaling pathways such as nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK). Various toxins are being studied as alternatives for cancer treatments, and bee venom and its active components are drawing attention as potential anticancer agents. The present study identifies novel anticancer peptides that target the oncoprotein against life-threatening cancer. Docking calculations indicate that anticancer peptides, namely Melittin, Phospholipase A2, Tertiapin, and Hyaluronidase bind TNF-α respectively with the lowest binding affinity. Interestingly, Mast cell degranulating (MCD) and Apamin have the highest binding affinity with TNF-α in comparison with the above four peptides. The two lead compounds namely MCD and Apamin have the highest docking score -1253.4 and -1067.8 respectively. The present study reveals that the bee venom peptides namely MCD and Apamin interact with TNF-α associated cancer for targeted therapy of cancer. These predicted anticancer peptides are valuable candidates for in vitro or in vivo peptide therapeutic drug studies against the TNF-α associated cancers.

Keywords

Peptides, Molecular docking, Bee venom, Anti-cancer

Introduction

Cancer is a dreadful disease that is one of the leading causes of death globally. According to current estimates, about 10 million new patients are diagnosed with cancer every year, which causes 6 million fatalities which account for nearly 12% of all deaths globally [1]. In 2020 a total of fifteen million new cancer cases are expected to be diagnosed with the number likely to exceed 20 million by 2025. It is also predicted that population expansion and aging would raise the number of new cancer cases to 21.7 million, with about 13 million cancer deaths by 2030 [2,3]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for the development of novel agents for the therapy of cancer. Biotoxins are generated by living organisms as a defense mechanism against predators with toxicological and pharmacological effects. Studies have reported that toxins derived from bee venom (BV) have an enormous anti-tumor potential [4]. Bee venom includes various active compounds, such as peptides and enzymes, that have the potential to cure inflammation and neurodegenerative disorders including Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [5]. Furthermore, bee venom has proven significant activity against different types of cancers including renal, lung, liver, prostate, bladder, and breast cancer as well as leukemia [4]. Multiple studies have detailed the biological actions of bee venom components and preclinical trials have been initiated to improve the potential use of bee venom components and its constituents as the next generation drugs [6]. Bee venom has a potential radioprotective, antimutagenic, anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive, and anticancer properties [7,8].

The major source of Bee venom is the Apis mellifera (female worker bee) which produces toxic polypeptides such as Mast Cell Degranulation (MCD), Melittin, Apamin, Adolapin, Tertiapin; enzymes such as Hyaluronidase and Phospholipase A2 (PLA2); and amino acids associated with non-peptide compounds such as histamine, norepinephrine, and dopamine [9]. The characteristics of bee venom are transparent liquid, odorless and it is acidic with a pH ranging from 4.5 to 5.5. The Bee venom constituents of 50% of melittin in its dry weight which has the properties such as hemolytic activity, surface action, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and antimicrobial activity shows its major role as a pharmacological and toxicological agent. Melittin induces apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells via the activation of the CAMKII-TAK1-JNK/p38 signaling pathway [5]. Apamin is a peptide with two disulfide bridges that could penetrate the blood-brain barrier, affecting central nervous system function through multiple mechanisms [10]. Mast cell degranulating (MCD) is a polypeptide with a similar structure to Apamin contains two disulfide bridges and accounts for 2-3% of dry weight in BV [11]. MCD is a potent anti-inflammatory peptide that is used to examine the secretory processes of inflammatory cells such as mast cells, basophils, and leukocytes [12]. Adolapin, an important peptide present in BV, has anti-inflammatory and antipyretic properties by reducing prostaglandin production and inhibiting cyclooxygenase activity [13]. Tertiapin is a 21 amino acids peptide in BV blocks inward-rectifier K+ channels found in epithelial cells, the heart, and the central nervous system. Tertiapin opposes G-protein-gated, acetylcholine-activated K+ currents which control the parasympathetic heart rate. This toxin is used to treat atrioventricular transmission abnormalities, although it is currently only used to modulate K+ channels [14,15]. Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) which has four disulfide bridges belongs to the group III sPLA2 enzymes. Phospholipase A2 can resist infection in various diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Asthma, and Parkinson’s disease [16]. The PLA2 also exhibits the anti-proliferative effect due to the substrate (phosphatidylinositol-3,4-bis phosphate) present in the PLA2 in major human tumor cells lines such as the human breast carcinoma cell line T-47D, the human bronchial epithelium cell line BEAS-2B, the human kidney carcinoma cell line A498, and the human prostate carcinoma cell line DU145. Taken together, BV has the potential to prevent and treat cancer in the future. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), a multifunctional pro-inflammatory cytokine, is responsible for inflammation-associated carcinogenesis [17]. It induces cell proliferation and survival in cancer cells by activating nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK). In addition, TNFα overexpression is associated with the invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis of tumor cells [18]. Thus, the ability of TNF to induce cancer renders it a potential therapeutic drug target. The current study investigates the role of bioactive peptides from bee venom to specifically target TNFα for cancer therapy.

Methods

Retrieval of bee venom peptides and TNF-α drug target

Bee venom (Apis. mellifera) peptides were retrieved from the UniProt database (UniportKB) (https://www.uniprot.org/). The Uniport IDs of 6 bee venom peptides are Melittin (P01501), Mast cell degranulating (P01499), Apamin (P01500), Tertiapin (P56587), PhospholipaseA2 (P00630), Hyaluronidase (Q08169). The protein data bank (PDB) (https://www.rcsb.org/) was used to retrieve the 3D coordinates of TNF-α (PDB ID:2AZ5).

Modeling of bee venom peptides from an animal source

To model the 3D structures of 6 2AZ5 peptides, I-TASSER was employed. I-TASSER (https://zhanggroup.org/I-TASSER/) constructs the 3D model in four consecutive stages: First, threading, where the query sequence is matched against a non-redundant sequence database by position-specific iteration in the first stage of I-TASSER. The second step is the structural assembly which performs the continuous threading alignment of fragments to build structural conformations of the well-aligned region with the unaligned parts generated via ab initio modeling. Next, the model selection and refinement that performs the fragment assembly simulation from the selected cluster centroids. Lastly, structure-based functional annotation structurally matches the predicted 3D models to proteins with known structure and function in the PDB [19].

Molecular docking analysis

The TNF-α structure was docked with the bee venom peptides using the ClusPro server (https://cluspro.bu.edu/login.php). ClusPro performs two critical steps to generate the docked complex. First, it uses the Fast Fourier Transform and operates on the PIPER systematic grid conformational software. In an electrostatic energy term, desolvation contributions are determined via a structure-based pairwise potential, and the van der Waals interaction energy is included in the docking score function. Next, the structures of the top 1,000 structures are clustered. After clustering, the hierarchical technique is employed to reduce the energy resulting in the elimination of the side chain available for collision using CHARMM potential [20].

Visualization and interaction of drug target - bee venom peptide complexes

Pymol software was used to view the docked protein-protein complex (https://pymol.org/2/). This is used to generate high-quality photos for publishing that are simple to use in molecular docking studies [21]. The free binding energy (ΔG) and the dissociation constant Kd (nm) at 25°C of the docked complex were analyzed by the PRODIGY server (https://wenmr.science.uu.nl/prodigy/) [22].

Results and Discussion

Modeling of bee venom peptides from an animal source

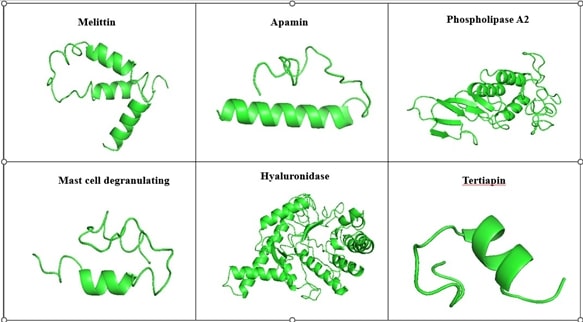

The bee venom peptide sequence was retrieved from the NCBI. The 3D structure of the peptide was constructed using I-Tasser which predicts based on the ten reference threading template, with confidence score values and Z score (Figure 1). The C score of the modeled peptide namely Melittin, Mast cell degranulating, Apamin, Tertiapin, PhospholipaseA2, and Hyaluronidase were found to be -2.70, -2.31, -2.28, -1.52, -0.71, and -0.50, respectively.

Figure 1. Modeled 3D structure of the Bee venom peptide by I-Tasser.

Molecular docking analysis

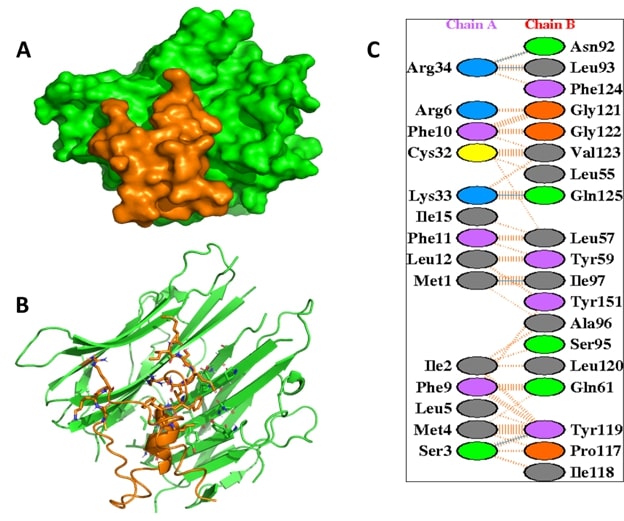

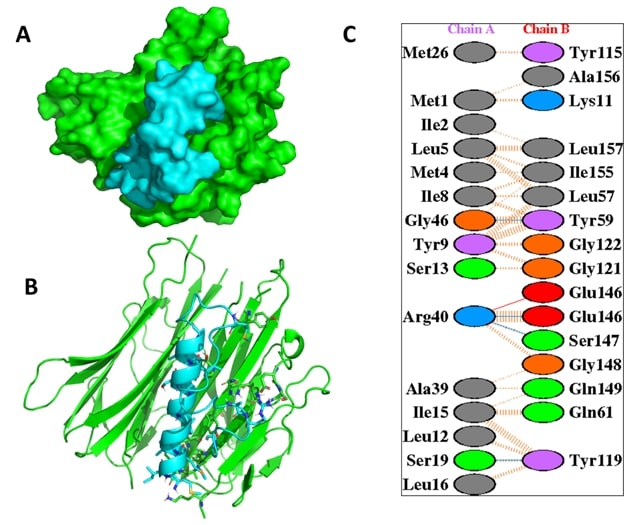

The docking analysis of TNF-α with 6 bee venom peptide revealed that the binding affinity of the docked complexes ranges from -916.5 to -1253.4 kcal/mol (Table 1). Interestingly, from the docking score it was found that 2 peptides namely; MCD and Apamin bind TNF-α with the highest docking scores of -1253.4 and -1067.8 kcal/mol, respectively. The active sites of the TNF alpha dimer interact with residues namely Leu57, Tyr59, Ser60, Gln61, Tyr119, Leu120, Gly121, Gly122, and Tyr151 for chain A while Leu57, Tyr59, Ser60, Tyr119, Leu120, Gly121, and Tyr151 for chain B [23]. Furthermore, the interaction analysis of the TNF-α-MCD and TNF-α-Apamin revealed that the active residues of TNF-α namely Tyr119 and Tyr-59 are involved in interaction with the BV peptides (Table 2). The interaction analysis of the TNF-α-MCD and TNF-α-Apamin are shown in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. In general, the lower binding energy of the docked complexes implies better binding affinity. The binding energy of the docked bee venom complexes was evaluated by the prodigy server which gives the free binding energy (ΔG) of the TNF-α-MCD and TNF-α-Apamin as -13.5 and -11.1 kcal/mol, respectively (Table 3)

|

S.No |

Peptide |

Length |

Sequence |

Docking Score |

|

1 |

Melittin |

70 |

MKFLVNVALVFMVVYISYIYAAPEPEPAPEPEAEADAEADPEAGIGAVLKVLTTGLPALISWIKRKRQQG |

-998.6 |

|

2 |

Apamin |

46 |

MISMLRCIYLFLSVILITSYFVTPVMPCNCKAPETALCARRCQQHG |

-1067.8 |

|

3 |

Phospholipase A2 |

167 |

MQVVLGSLFLLLLSTSHGWQIRDRIGDNELEERIIYPGTLWCGHGNKSSGPNELGRFKHTDACCRTHDMCPDVMSAGESKHGLTNTASHTRLSCDCDDKFYDCLKNSADTISSYFVGKMYFNLIDTKCYKLEHPVTGCGERTEGRCLHYTVDKSKPKVYQWFDLRKY |

-1030.3 |

|

4 |

Mast cell degranulating |

50 |

MISMLRCTFFFLSVILITSYFVTPTMSIKCNCKRHVIKPHICRKICGKNG |

-1253.4 |

|

5 |

Tertiapin |

21 |

ALCNCNRIIIPHMCWKKCGKK |

-916.5 |

|

6 |

Hyaluronidase |

382 |

MSRPLVITEGMMIGVLLMLAPINALLLGFVQSTPDNNKTVREFNVYWNVPTFMCHKYGLRFEEVSEKYGILQNWMDKFRGEEIAILYDPGMFPALLKDPNGNVVARNGGVPQLGNLTKHLQVFRDHLINQIPDKSFPGVGVIDFESWRPIFRQNWASLQPYKKLSVEVVRREHPFWDDQRVEQEAKRRFEKYGQLFMEETLKAAKRMRPAANWGYYAYPYCYNLTPNQPSAQCEATTMQENDKMSWLFESEDVLLPSVYLRWNLTSGERVGLVGGRVKEALRIARQMTTSRKKVLPYYWYKYQDRRDTDLSRADLEATLRKITDLGADGFIIWGSSDDINTKAKCLQFREYLNNELGPAVKRIALNNNANDRLTVDVSVDQV |

-1014.1 |

|

Peptide |

Peptide residues |

Protein |

Protein residues |

Distance |

Nature of interaction |

|

MCD |

ARG 34 ARG 34 MET 2 SER 3 LYS 33 PHE 11 LEU 12 ILE 15 SER 3 ILE 2 MET 4 |

TNF-α

|

ASN 92 LEU 93 ILE 97 TYR 119 GLN 125 LEU 57 TYR 59 LEU 57 TYR 119 TYR 119 TYR 119 |

2.72 2.62 2.93 2.97 2.66 3.89 3.81 3.77 2.97 3.60 3.61 |

Hydrogen Bond Hydrogen Bond Hydrogen Bond Hydrogen Bond Hydrogen Bond Vanderwaals Vanderwaals Vanderwaals Vanderwaals Vanderwaals Vanderwaals |

|

Apamin |

GLY 46 SER 19 ARG 40 ARG 40 ARG 40 LEU 12 SER 13 MET 1 LEU 5 |

TNF-α |

TYR 59 TYR 119 GLU 146 SER 147 GLU 146 TYR 119 GLY 121 LYS 11 LEU 57 |

2.67 2.98 2.75 2.62 2.75 3.69 3.85 3.37 3.70 |

Hydrogen Bond Hydrogen Bond Hydrogen Bond Hydrogen Bond Salt bridge Vanderwaals Vanderwaals Vanderwaals Vanderwaals |

Figure 2. The interaction analysis of the TNF-α with Mast Cell Degranulation (MCD). (A) illustrates the surface view of the complex and (B) represents the interaction of of TNF-α (green) with MCD peptide (orange). The key residues of TNF-α involved in non-covalent interaction with MCD (C).

Figure 3. The interaction analysis of TNF-α with Apamin.

|

Docked complexes |

ΔG (kcal/mol) |

Kd (nM) at 25°C |

Number of Interfacial Contacts (ICs) Per Property |

Non Interacting Surface (NIS) per property |

||||||

|

|

|

|

ICs Charged -charged |

ICs Charged -polar |

ICs Charged -apolar |

ICs polar -polar |

ICs polar -apolar |

ICs apolar-apolar |

NIS charged (%) |

NIS apolar (%) |

|

TNF-α-Apamin |

-11.1 |

6.7E-09 |

1 |

6 |

20 |

7 |

25 |

49 |

21.70 |

43.87 |

|

TNF-α-Hyaluronidase |

-11.8 |

2.1E-09 |

1 |

9 |

26 |

7 |

25 |

51 |

26.57 |

39.85 |

|

TNF-α-MCD |

-13.5 |

1.3E-10 |

1 |

9 |

29 |

8 |

32 |

52 |

21.80 |

43.60 |

|

TNF-α-Melittin |

-10.9 |

1.0E-08 |

3 |

7 |

19 |

7 |

35 |

40 |

21.20 |

46.08 |

|

TNF-α-Phospholipase A2 |

-11.1 |

6.8E-09 |

1 |

6 |

16 |

7 |

27 |

45 |

21.85 |

44.12 |

|

TNF-α-Tertiapin |

-10.5 |

1.9E-08 |

1 |

7 |

16 |

7 |

25 |

47 |

21.05 |

45.45 |

Conclusion

In silico methods play an ever-increasing role in designing novel therapeutic peptides for targeted therapy of cancer. Virtual screening approaches in drug development makes the process pertinent to reduce the cost and time. The bee venom is composed of more than 40 active ingredients that has been reported to have potential analgesic, antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. Toxins derived from various organisms have been clinically evaluated to treat oncological diseases. For example, botulin toxin has an anesthetic effect and was found to trigger apoptosis in tumor cells. In this study, the TNF-α is docked with a bee venom peptide due to their anticancer properties and analyzed with the 6 bee venom peptides using in silico approach. The retrieved sequence of bee venom peptide was modeled to obtain the tertiary structure and docked with TNF-α. The negative values of the free binding energy of the MCD and Apamin show the energetic feasibility of the complex formation. In conclusion, the current study indicates that bioactive compounds from bee venom could be potential candidates for the future treatment of cancer disease.

References

2. Zugazagoitia J, Guedes C, Ponce S, Ferrer I, Molina-Pinelo S, Paz-Ares L. Current challenges in cancer treatment. Clinical Therapeutics. 2016 Jul 1;38(7):1551-66.

3. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet‐Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global Cancer Statistics, 2012. CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2015 Mar;65(2):87-108.

4. Oršolić N. Bee venom in cancer therapy. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2012 Jun;31:173-94.

5. Wehbe R, Frangieh J, Rima M, El Obeid D, Sabatier JM, Fajloun Z. Bee venom: Overview of main compounds and bioactivities for therapeutic interests. Molecules. 2019 Aug 19;24(16):2997.`

6. Pucca MB, Cerni FA, Oliveira IS, Jenkins TP, Argemí L, Sørensen CV, et al. Bee updated: current knowledge on bee venom and bee envenoming therapy. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019 Sep 6;10:2090.

7. Liu X, Chen D, Xie L, Zhang R. Effect of honey bee venom on proliferation of K1735M2 mouse melanoma cells in‐vitro and growth of murine B16 melanomas in‐vivo. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2002 Aug;54(8):1083-9.

8. Nam KW, Je KH, Lee JH, Han HJ, Lee HJ, Kang SK, et al. Inhibition of COX-2 activity and proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β) production by water-soluble sub-fractionated parts from bee (Apis mellifera) venom. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 2003 May;26:383-8.

9. Habermann E. Bee and Wasp Venoms: The biochemistry and pharmacology of their peptides and enzymes are reviewed. Science. 1972 Jul 28;177(4046):314-22.

10. Gu H, Han SM, Park KK. Therapeutic effects of apamin as a bee venom component for non-neoplastic disease. Toxins. 2020 Mar 19;12(3):195.

11. Hanson JM, Morley J, Soria-Herrera C. Anti-inflammatory property of 401 (MCD-peptide), a peptide from the venom of the bee Apis mellifera (L.). British Journal of Pharmacology. 1974 Mar;50(3):383.

12. Banks BE, Dempsey CE, Vernon CA, Warner JA, Yamey J. Anti-inflammatory activity of bee venom peptide 401 (mast cell degranulating peptide) and compound 48/80 results from mast cell degranulation in vivo. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1990 Feb;99(2):350.

13. Shkenderov S, Koburova K. Adolapin-a newly isolated analgetic and anti-inflammatory polypeptide from bee venom. Toxicon. 1982 Jan 1;20(1):317-21.

14. Drici MD, Diochot S, Terrenoire C, Romey G, Lazdunski M. The bee venom peptide tertiapin underlines the role of IKACh in acetylcholine‐induced atrioventricular blocks. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2000 Oct;131(3):569-77.

15. Cornara L, Biagi M, Xiao J, Burlando B. Therapeutic properties of bioactive compounds from different honeybee products. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2017:412.

16. Park S, Baek H, Jung KH, Lee G, Lee H, Kang GH, et al. Bee venom phospholipase A2 suppresses allergic airway inflammation in an ovalbumin‐induced asthma model through the induction of regulatory T cells. Immunity, Inflammation and Disease. 2015 Dec;3(4):386-97.

17. Wang X, Lin Y. Tumor necrosis factor and cancer, buddies or foes? 1. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2008 Nov;29(11):1275-88.

18. Aggarwal BB. Signalling pathways of the TNF superfamily: a double-edged sword. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2003 Sep 1;3(9):745-56.

19. Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y. I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nature Protocols. 2010 Apr;5(4):725-38.

20. Ghani U, Desta I, Jindal A, Khan O, Jones G, Hashemi N, et al. Improved docking of protein models by a combination of alphafold2 and cluspro. BioRxiv. 2021 Sep 7:2021-09.

21. Seeliger D, de Groot BL. Ligand docking and binding site analysis with PyMOL and Autodock/Vina. Journal of Computer-Aided MolecularDdesign. 2010 May;24(5):417-22.

22. Xue LC, Rodrigues JP, Kastritis PL, Bonvin AM, Vangone A. PRODIGY: a web server for predicting the binding affinity of protein–protein complexes. Bioinformatics. 2016 Dec 1;32(23):3676-8.

23. Zia K, Ashraf S, Jabeen A, Saeed M, Nur-e-Alam M, Ahmed S, et al. Identification of potential TNF-α inhibitors: from in silico to in vitro studies. Scientific Reports. 2020 Dec 1;10(1):1-9.