Abstract

The consequence of pesticides on human health is a significant area of research. Different types of pesticides can cause various side effects on our body systems, including our organs and glands. One notable effect is on the gonads, which are the glands responsible for producing male and female sex hormones. The effects can be severe, leading to infertility in men and women, as well as other health issues. Thus, it is essential to focus on developing plant-based pesticides, known as botanical pesticides, which are derived from the various parts of plants (such as roots, stems, leaves, flowers, seeds, and fruits) and can be used in either dry powder or liquid form. Additionally, there is a need for innovation in creating new artificial pesticides, or synthetic pesticides, in laboratories. This includes modifying existing pesticides to make them biodegradable over time, that is they have minimal or no adverse effects on human health.

Keywords

Pesticides, Endocrine system, Gonads, Human health

Introduction

This article provides an overview of the effects of pesticides on reproductive organs and overall human health. It highlights recent findings and offers an updated perspective on how exposure to these chemicals can influence gonadal function and cause various health issues. To ensure that every individual globally has access to food, the "Green Revolution" was initiated, starting in numerous nations post-World War II and at the end of the 19th century into the early 20th century, and continuing thereafter. This agrarian transformation included biotechnology, genetic modification, and pest management. In pest management, different chemicals, including pesticides, were produced to mitigate damage caused by pests, thereby allowing for the production and storage of crops for the necessary duration. Literature surveys indicate that these pesticides directly or indirectly enter the human body since humans are at the highest level in all food chains [1–11]. Various categories of these pesticides have distinct impacts on the body's systems: digestive, respiratory, circulatory, excretory, reproductive, endocrine, and nervous system. Additionally, our focus here is solely on reproductive systems, specifically gonads.

Commentary Discussion

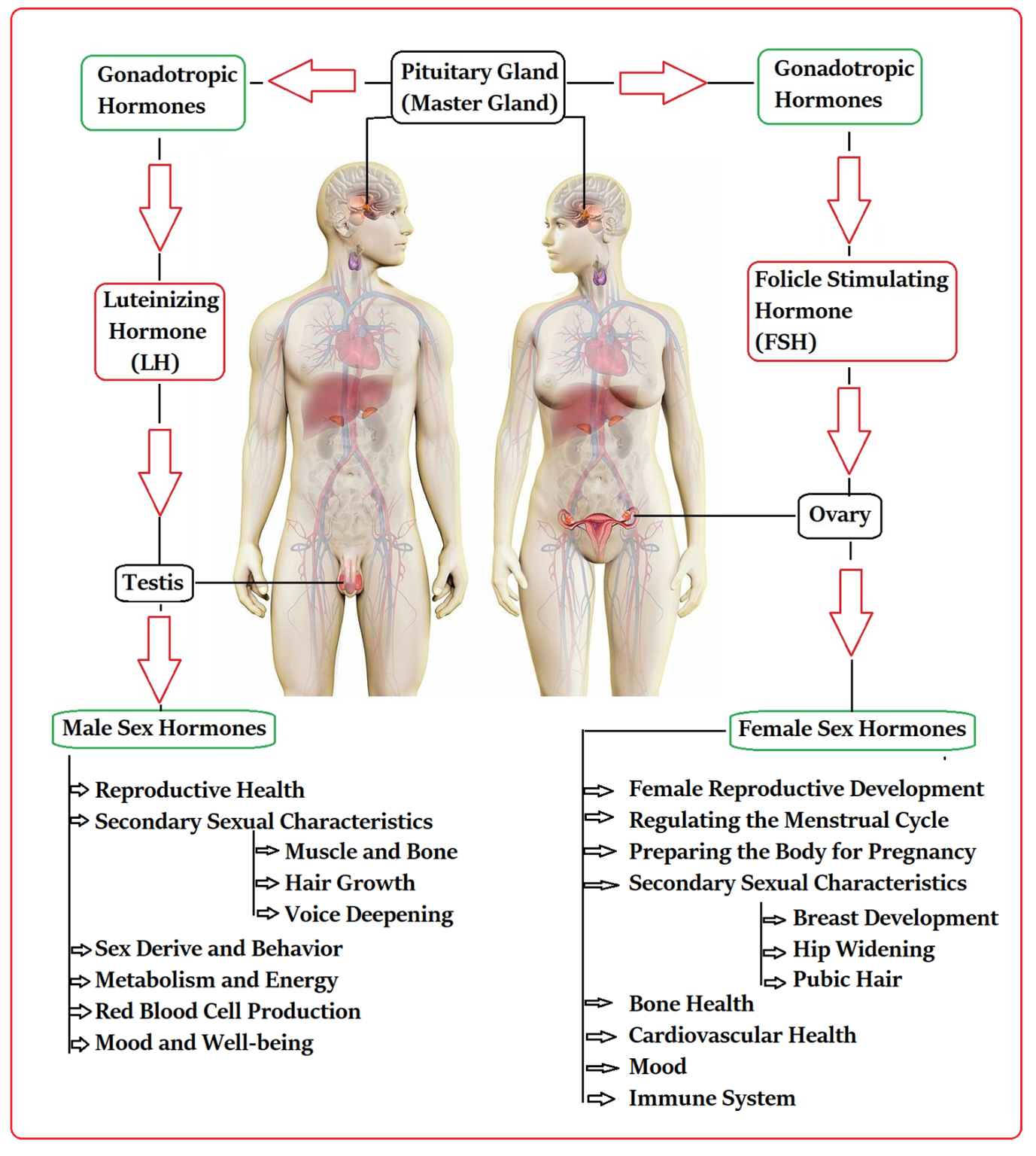

The production and secretion of male (♂) and female (♀) sex hormones are intricately regulated by gonadotropic hormones released by the master gland, as shown in Figure 1. When these vital processes are disrupted by pesticides, serious health issues can arise, including the abnormal functioning of organs. Extensive literature reviews underscore the alarming link between various pesticides (considering their types, levels of exposure, and detrimental impacts) and gonadal health, which directly influences human well-being [12–23]. It is crucial to address these concerns to protect our health interests.

Figure 1. Mechanism of release of sex hormones from the gonads.

Castiello and Freire [8] found that (i) exposure to organophosphate pesticides is connected to delayed sexual maturation in both boys and girls, (ii) childhood exposure to pyrethroids is related to delayed puberty in girls and earlier puberty in boys, and (iii) prenatal/childhood exposure to various pesticides has been associated with earlier puberty onset in girls and delayed puberty in boys.

Bretveld et al. [15] authored a review titled, “Pesticide exposure: the hormonal function of the female reproductive system disrupted?” This review outlined various ways pesticides can interfere with the hormonal function of the female reproductive system, specifically the ovarian cycle. They determined that contact with pesticides could be linked to disruptions in the menstrual cycle, decreased fertility, extended time to conceive, miscarriage, stillbirths, and developmental abnormalities. Farr et al. [16] employed Cox proportional hazards modeling to investigate the relationship between pesticide use and age at menopause in 8,038 women residing and working on farms in Iowa and North Carolina. The research indicated that the median time to menopause rose by about 3 months for women exposed to pesticides (hazard ratio = 0.87, 95% confidence interval: 0.78, 0.97) and by roughly 5 months for those who used hormonally active pesticides (hazard ratio = 0.77, 95% confidence interval: 0.65, 0.92).

Roychoudhury et al. [17] also discussed pesticide contamination in their review. They documented the impacts of pesticides on (i) altered levels of luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and testosterone caused by imidacloprid, (ii) anti-androgenic effects and hormonal imbalances in the body displayed by hypogonadism from dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) exposure, and (iii) reduced testosterone concentrations from acute exposure to carbamates, thio- and dithiocarbamates, pyrethroids, chlorophenoxy acids, chloromethylphosphonic acids, and organophosphates. Research featured by Glover et al. in the Journal of Endocrinological Investigation [18] indicated that exposure to the insecticide chlorpyrifos and various organophosphates (OPs) are positively linked to the onset of erectile dysfunction (ED). ED, referred to as impotence, is the challenge of achieving or maintaining an erection. ED leads to drawbacks such as a diminished sex life, depression, reduced self-worth, and troubled relationships, along with possible health concerns like an increased risk of heart disease, stroke, and various circulatory problems. It can lead to discomfort for both the person and their partner. Kaur et al. [19] revealed the possible mechanisms of pesticide effects on erectile function, a contributing factor in male infertility. They discovered that acetamiprid has the most harmful impact, leading to erectile dysfunction by affecting various inhibitory pathways. Acetamiprid is a neonicotinoid pesticide that manages a variety of sucking and chewing insects, including aphids, whiteflies, and leafhoppers, by affecting the insect's central nervous system. In 2023, Hamed et al. [20] in their meta-analysis used a total of 766 male subjects, out of which 349 were exposed to OP pesticides and rest 417 were unexposed controls. The findings of this research indicate that exposure to OP pesticide leads to decreased sperm count, concentration, total and progressive motility, and normal sperm morphology, potentially through a mechanism independent of testosterone. These results reinforce the current evidence in the literature regarding the adverse effects of OP pesticide exposure on semen quality. Cremonese et al. [21] documented the effects of agricultural pesticides on reproductive hormones, semen quality, and genital measurements in young men in the southern region of Brazil. Rural men exposed to agricultural pesticides exhibited worse sperm morphology, increased sperm count, and reduced LH levels compared to urban individuals. They determined that prolonged occupational exposure to contemporary pesticides could influence reproductive results in young males.

La Merrill et al. [7] authored a research paper titled, “Prenatal Exposure to the Pesticide DDT and Hypertension Diagnosed in Women before Age 50: A Longitudinal Birth Cohort Study” and found that (i) adult women may experience heightened hypertension due to exposure to p,p´-DDT in early life, and (ii) the link between DDT exposure and hypertension may originate early in developmental stages. Tyagi et al. [5] determined in their study that the concentration of organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) in the environment may significantly influence the development of diabetes. Mohammadkhani et al. stated that exposure to OCPs is linked to a higher risk of Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality from CVD, mediated by atherogenic and inflammatory molecular mechanisms affecting fatty acid and glucose metabolism [6]. Three pesticides namely malathion, diazinon, and glyphosate were classified category 2A carcinogens to humans [9–11].

Every class of plants of India (algae [24], bryophytes [25], pteridophytes [26], gymnosperms [27], and angiosperms [28]) possesses particular medicinal or toxicological properties, or sometimes both [29]. Plants act as natural pesticides by producing secondary metabolites (alkaloids, terpenes, limonoids, etc.) that may repel, harm, or affect the development of pests [30]. Certain plants that possess pesticidal characteristics (botanical pesticides) are familiar to us. Examples include neem (azadirachtin) [31], Chrysanthemum cinerariifolium (pyrethrum) [32], Leguminosae family plants (rotenone) [33], strychnine tree (strychnine) [34], clove, coriander, and mint plants (repellent activity) [35], among others. Azadirachtin serves as an effective insect growth regulator and antifeedant, deterring pests while interfering with their growth and reproduction without causing instant death. Neem oil, a widely used neem pesticide, is derived from fruits and seeds, containing these active ingredients, necessitating emulsifiers to blend with water for application [31]. Pyrethrins originate from the desiccated flower blooms of the Chrysanthemum plant. Pyrethrins consist of a blend of six insecticidal substances, which include cinerin, jasmolin, and different types of pyrethrins. Pyrethrins function as a quick-acting contact insecticide, affecting the nervous system of insects and leading to swift paralysis, or "knockdown". The derived compounds are utilized to produce a range of insecticidal items, including sprays and lotions, aimed at managing pests such as flies, mosquitoes, and fleas [32]. Rotenone is utilized globally due to its wide-ranging insecticidal, acaricidal, and various pesticidal characteristics. All plants recognized for producing rotenone belong to the natural order Leguminos. Rotenone is utilized globally due to its wide-ranging insecticidal, acaricidal, and additional pesticidal characteristics [33]. All plants recognized for producing rotenone belong to the natural order Leguminos. Rotenone is extremely poisonous to various insects but completely safe for humans and all warm-blooded vertebrates. Although not every insect is vulnerable to its harmful effects, it has been demonstrated, in the form of sprays and various formulations, to be fifteen times more toxic than a nicotine spray when applied as a contact poison on aphids, and thirty times more toxic than lead arsenate, when evaluated as an internal poison against specific caterpillars. The seeds of the strychnine tree (Strychnos nux-vomica) hold the extremely poisonous alkaloid strychnine, which has been commonly utilized as a potent yet hazardous pesticide. It is mainly utilized to eliminate small vertebrates, including rodents and birds [34]. Botanical pesticides are typically less harmful to non-target species, humans, and the ecosystem. They decompose into non-toxic materials, minimizing environmental harm. They provide a sustainable and renewable option to artificial pesticides. The intricate and varied chemical makeup can hinder pests from developing resistance more effectively. Thus, the main aim of botanists should be to search for other wild plants that have pesticidal properties.

Conclusion

There are already all classes of plants with natural pesticidal properties; therefore, their use should be increased and encouraged globally among farmers. Because exposure to some pesticides (synthetic) resulted in: (i) early/delayed puberty in boys, (ii) decreased semen quality (including low sperm count, reduced sperm mobility, failure to inseminate the ovum ), (iii) erectile dysfunction in male, (iv) early puberty (fertility) and early menopause (infertility) in girls, (v) loss of gestation in females (natural implantation of embryo in uterus), (vi) other health issues including (vii) aggressiveness, (viii) anxiety, (ix) hypertension, (x) diabetes, (xi) cardiovascular disease and (xii) cancer. Therefore, we commented that attention should be given to time dependent biodegradable synthetic pesticides (chemicals) with no/minimal side effects and more attention is given to natural (botanical) pesticides.

Acknowledgement

The paper is dedicated to our beloved teacher, mentor, and guru father respected Professor (Dr.) P. P. Singh (D.Sc., F.A.N.Sc. and Bharat Siksha Ratan Awardee) on his 94th birthday.

References

2. Mnif W, Hassine AI, Bouaziz A, Bartegi A, Thomas O, Roig B. Effect of endocrine disruptor pesticides: a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011 Jun;8(6):2265–303.

3. Leemans M, Couderq S, Demeneix B, Fini JB. Pesticides With Potential Thyroid Hormone-Disrupting Effects: A Review of Recent Data. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019 Dec 9;10:743.

4. Huang J, Hu L, Yang J. Dietary Magnesium Intake Ameliorates the Association Between Household Pesticide Exposure and Type 2 Diabetes: Data From NHANES, 2007-2018. Front Nutr. 2022 May 20;9:903493.

5. Tyagi S, Mishra BK, Sharma T, Tawar N, Urfi AJ, Banerjee BD, et al. Level of Organochlorine Pesticide in Prediabetic and Newly Diagnosed Diabetes Mellitus Patients with Varying Degree of Glucose Intolerance and Insulin Resistance among North Indian Population. Diabetes Metab J. 2021 Jul;45(4):558–68.

6. Mohammadkhani MA, Shahrzad S, Haghighi M, Ghanbari R, Mohamadkhani A. Insights into Organochlorine Pesticides Exposure in the Development of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review. Arch Iran Med. 2023 Oct 1;26(10):592–9.

7. La Merrill M, Cirillo PM, Terry MB, Krigbaum NY, Flom JD, Cohn BA. Prenatal exposure to the pesticide DDT and hypertension diagnosed in women before age 50: a longitudinal birth cohort study. Environ Health Perspect. 2013 May;121(5):594–9.

8. Castiello F, Freire C. Exposure to non-persistent pesticides and puberty timing: a systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. Eur J Endocrinol. 2021 May 4;184(6):733–49.

9. Cressey D. Widely used herbicide linked to cancer. Nature. 2015 Mar 24;24:1–3.

10. Jones RR, Barone-Adesi F, Koutros S, Lerro CC, Blair A, Lubin J, et al. Incidence of solid tumours among pesticide applicators exposed to the organophosphate insecticide diazinon in the Agricultural Health Study: an updated analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2015 Jul;72(7):496–503.

11. Anjitha R, Antony A, Shilpa O, Anupama KP, Mallikarjunaiah S, Gurushankara HP. Malathion induced cancer-linked gene expression in human lymphocytes. Environ Res. 2020 Mar;182:109131.

12. Toft G, Hagmar L, Giwercman A, Bonde JP. Epidemiological evidence on reproductive effects of persistent organochlorines in humans. Reprod Toxicol. 2004 Nov;19(1):5–26.

13. Rizwan S, Ahmad I, Ashraf M, Aziz S, Yasmine T, Sattar A. Advance effect of pesticides on reproduction hormones of women cotton pickers. Pak J Biol Sci. 2005;8(11):1588–91.

14. Kumar S, Sharma A, Kshetrimayum C. Environmental & occupational exposure & female reproductive dysfunction. Indian J Med Res. 2019 Dec;150(6):532–45.

15. Bretveld RW, Thomas CM, Scheepers PT, Zielhuis GA, Roeleveld N. Pesticide exposure: the hormonal function of the female reproductive system disrupted? Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2006 May 31;4:30.

16. Farr SL, Cai J, Savitz DA, Sandler DP, Hoppin JA, Cooper GS. Pesticide exposure and timing of menopause: the Agricultural Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006 Apr 15;163(8):731–42.

17. Roychoudhury S, Chakraborty S, Choudhury AP, Das A, Jha NK, Slama P, et al. Environmental Factors-Induced Oxidative Stress: Hormonal and Molecular Pathway Disruptions in Hypogonadism and Erectile Dysfunction. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021 May 24;10(6):837.

18. Glover F, Mehta A, Richardson M, Muncey W, Del Giudice F, Belladelli F, et al. Investigating the prevalence of erectile dysfunction among men exposed to organophosphate insecticides. J Endocrinol Invest. 2024 Feb;47(2):389–99.

19. Kaur RP, Gupta V, Christopher AF, Bansal P. Potential pathways of pesticide action on erectile function–a contributory factor in male infertility. Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction. 2015 Dec 1;4(4):322–30.

20. Hamed MA, Akhigbe TM, Adeogun AE, Adesoye OB, Akhigbe RE. Impact of organophosphate pesticides exposure on human semen parameters and testosterone: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023 Oct 24;14:1227836.

21. Cremonese C, Piccoli C, Pasqualotto F, Clapauch R, Koifman RJ, Koifman S, et al. Occupational exposure to pesticides, reproductive hormone levels and sperm quality in young Brazilian men. Reprod Toxicol. 2017 Jan;67:174–85.

22. Lwin TZ, Than AA, Min AZ, Robson MG, Siriwong W. Effects of pesticide exposure on reproductivity of male groundnut farmers in Kyauk Kan village, Nyaung-U, Mandalay region, Myanmar. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2018 Nov 29;11:235–41.

23. LeBlanc GA, Bain LJ, Wilson VS. Pesticides: multiple mechanisms of demasculinization. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1997 Jan 3;126(1):1–5.

24. Asimakis E, Shehata AA, Eisenreich W, Acheuk F, Lasram S, Basiouni S, et al. Algae and Their Metabolites as Potential Bio-Pesticides. Microorganisms. 2022 Jan 27;10(2):307.

25. Abay G, Karakoç ÖC, Tüfekçi AR, Koldaş S, Demirtas I. Insecticidal activity of Hypnum cupressiforme (Bryophyta) against Sitophilus granarius (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Journal of Stored Products Research. 2012 Oct 1;51:6–10.

26. Annapoorneshwari M, Sharma A, Hegde S. LysM domain-containing chitinases in pteridophytes: A promising resource for sustainable biopesticides. Plant Biol (Stuttg). 2025 Aug 13.

27. Huang SQ, Zhang ZX. Anti-insect activity of the methanol extracts of fern and gymnosperm. Agricultural Sciences in China. 2010 Feb 1;9(2):249–56.

28. Mossa AT. Green pesticides: Essential oils as biopesticides in insect-pest management. Journal of environmental science and technology. 2016 Sep 1;9(5):354.

29. Giri VP, Pandey S, Singh SP, Kumar B, Zaidi SF, Mishra A. Medicinal plants associated microflora as an unexplored niche of biopesticide. In: Rakshit A, Meena VS, Abhilash PC, Sarma BK, Singh HB, Fraceto L, et al., Editors. Biopesticides. Sawston, UK: Woodhead Publishing; 2022. pp. 247–59.

30. Secoy DM, Smith AE. Use of plants in control of agricultural and domestic pests. Economic Botany. 1983 Jan;37(1):28–57.

31. Tulashie SK, Adjei F, Abraham J, Addo E. Potential of neem extracts as natural insecticide against fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith)(Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering. 2021 Dec 1;4:100130.

32. Hodoșan C, Gîrd CE, Ghica MV, Dinu-Pîrvu CE, Nistor L, Bărbuică IS, et al. Pyrethrins and Pyrethroids: A Comprehensive Review of Natural Occurring Compounds and Their Synthetic Derivatives. Plants (Basel). 2023 Nov 29;12(23):4022.

33. Xu W, Shen D, Chen X, Zhao M, Fan T, Wu Q, et al. Rotenone nanoparticles based on mesoporous silica to improve the stability, translocation and insecticidal activity of rotenone. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023 Oct;30(48):106047–58.

34. Patocka J. Strychnine. In: Gupta RC, editor. Handbook of toxicology of chemical warfare agents. New York: Academic Press; 2015. pp. 239–47.

35. Ramsha A, Saleem KA, Saba B. Repellent activity of certain plant extracts (clove, coriander, neem and mint) against red flour beetle. Am Sci Res J Eng Technol Sci. 2019;55:83–91.