Abstract

An investigation of comprehensive changes and shared dysregulated signaling pathways across acne patients in the early stages remains largely unexplored. In our recently published paper entitled “Analysis of Intracellular Communication Reveals Consistent Gene Changes Associated with Early-Stage Acne Skin,” we utilized single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial RNA-seq datasets from acne patients to analyze cell communication. We identified dysregulated genes associated with inflammatory responses and hyperkeratinization. This commentary discusses new potential markers in major skin cell types, including endothelial cells, fibroblasts, lymphocytes, myeloid cells, keratinocytes, and smooth muscle cells. We also discuss key dysregulated genes associated with inflammation and hyperkeratinization in acne lesions, focusing on the intricate interplay between these processes. Based on our findings, we discussed potential FDA-approved treatments targeting two key pathways involved in acne pathogenesis. These insights offer new therapeutic targets for acne treatment.

Keywords

Acne vulgaris, Cell-cell interaction, Early-stage of acne, Cell markers in the skin, Inflammatory response, TREM2 macrophages, GRN-SORT1, Hyperkeratinization, Keratinocyte, IL-13-IL13-RA1

Abbreviations

C. acnes: Cutibacterium acnes; scRNA-seq: Single-cell RNA sequencing; SORT1: Sortilin 1; TLRs: Toll-like receptors; NF-κB Signaling Pathway: Nuclear Factor Kappa-Light-Chain- Enhancer of Activated B cells Signaling Pathway; NLRP3: NOD-like Receptor Protein 3; MAPK Pathway: Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling Pathway; AMPs: Antimicrobial Peptides; HPK: Human Primary Keratinocyte; NHEK: Normal Human Epidermal Keratinocytes; HPV-KER: Human Papillomavirus- Immortalized Keratinocyte; PBMCs: Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells; GRN: Granulin Precursor

Commentary

Acne vulgaris, the most common skin condition worldwide, affects over 85% of adolescents, with nearly half continuing to experience it into adulthood. The Scarring and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation associated with acne can profoundly impact mental health and self-esteem, underscoring the importance of early and effective treatment [1]. Acne is more than a cosmetic issue; similar to other chronic multifactorial inflammatory diseases, it is a chronic, multifactorial inflammatory disease characterized by intricate interactions between host cells, dysregulated signaling pathways, and genetic factors, alongside the influence of the microbiota [2-8]. These dynamic interactions contribute to four key pathological processes in acne-affected skin: inflammation, hyperkeratinization, seborrhea, and the accumulation of Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes) within the pilosebaceous unit (PSU) [9]. Among them, hyperkeratinization leads to clogged pores, while seborrhea, marked by excessive sebum production, creates an environment conducive to C. acnes overgrowth. This bacterial proliferation and the eventual rupture of the PSU trigger an immune response, fueling localized inflammation and further disrupting skin homeostasis. These interconnected processes form the basis of acne pathogenesis, emphasizing its complexity as a disease beyond surface-level manifestations [10]. This commentary builds upon our previous work [11], presenting new findings on potential markers in major skin cell types, key dysregulated genes linked to inflammation and hyperkeratinization, and the interplay between these processes. These findings enhance our understanding of acne pathogenesis and may serve as a basis for further research into inflammatory skin diseases.

New Potential Markers for Annotating Major Skin Cell Types in Transcriptomic Data

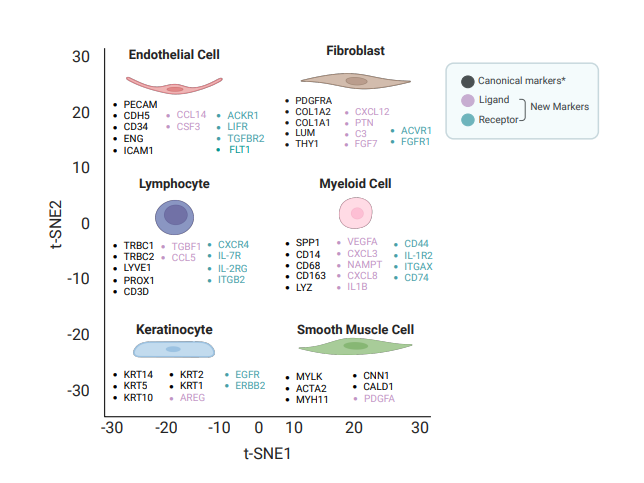

New cell markers are essential for defining and annotating cell types in advanced technologies such as single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial RNA-seq. These tools can reveal cellular heterogeneity with unprecedented resolution, facilitating detailed analysis of diversity and dynamic changes that are crucial for understanding the complex process of tissue development. However, accurately annotating cell types remains challenging, as it relies on reliable markers to differentiate closely related cell types and subtypes; the absence of precise markers can lead to misclassification and obscure critical biological insights. In our study, we addressed this challenge by identifying new gene products that function as ligands and receptors in signaling pathways, offering potential cell markers for annotating major skin cell types [11]. For endothelial cells, we identified the ligands CCL14 and CSF3, along with the receptors ACKR1, LIFR, FLT1, and TGFBR2. In fibroblasts, we found ligands such as CXCL12, PTN, C3, and FGF7, as well as receptors including PDGFRA, SDC2, ACVR1, and FGFR1. Similarly, in lymphocytes, we identified the ligands TGFB1 and CCL5, and the receptors CXCR4, IL-7R, IL-2RG, and ITGB2. For myeloid cells, the ligands NAMPT, CXCL8, IL1B, VEGFA, and CXCL3 were identified alongside receptors CD74, CD44, IL-1R2, and ITGAX. In keratinocytes, we found the ligand AREG and the receptors EGFR and ERBB2, while PDGFA was identified as the ligand in smooth muscle cells [11] (Figure 1). These findings reveal critical roles for these genes in signal transduction and cell-specific functions, advancing our ability to annotate and understand the diverse cell types in the skin. To validate these findings, we analyzed two published skin scRNA-seq datasets and plan to use experimental approaches such as multiple channel immunofluorescence [12,13] and flow cytometry [14,15] to further validate these markers with specific cell types in skin biopsies in a future study. We will use samples from C. acnes and squalene-induced acne mouse models [16], with non-induced mice as controls. Additionally, biopsies from acne patients and healthy controls (individuals without acne) will be analyzed. However, obtaining human samples presents significant challenges due to ethical concerns about scarring, as patients may be reluctant to undergo skin biopsy procedures. Moreover, using the mouse model presents limitations, as acne is a uniquely human disease, and the mouse model cannot fully replicate the complex human pathogenesis of acne [16]. We also included five canonical markers for each cell type. For instance, Lum serves as a marker for fibroblasts in both skin and intestine [11,17]. KRT14 is included in our marker set for annotating keratinocytes in the heatmap. Consistent with our data, KRT14 is also a well-established marker for keratinocytes and is widely applied in the design of transgenic mouse models for epidermal gene knockout studies in skin such as Paget's disease [18]. Integrating our novel markers with these previously identified canonical markers [19-22] will enhance the accuracy of downstream analyses and establish a robust framework for transcriptomic data (Figure 1).

Figure 1: New potential markers for annotating major skin cell types in transcriptomic data. The chosen five canonical markers (black), ligands (light purple), and receptors (blue-green) are associated with various cell types including endothelial cells, fibroblasts, lymphocytes, myeloid cells, keratinocytes, and smooth muscle cells. Ligands and receptors were validated across two published skin datasets [22,62] *For simplicity, only five key canonical markers are included, though we acknowledge that additional markers have been reported in the literature. Due to page limitations, we did not subset these major cell types or list their markers.

Key Genes Driving Inflammatory Responses in Acne

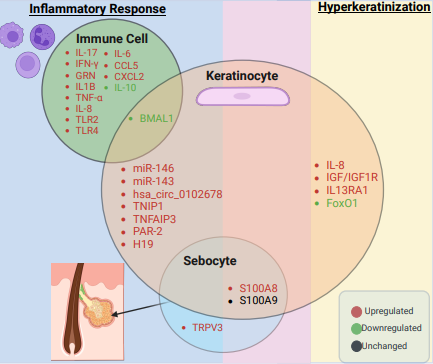

The inflammatory response is a key component of acne pathogenesis, driven by the interaction of C. acnes with host immune pathways. Toll-like receptors 2 (TLR2), predominantly expressed in macrophages surrounding the PSU, [9] is a key mediator in this process. Activation of TLR2 by C. acnes triggers the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling pathway. The NF-κB pathway is a central regulator of inflammation and immunity. Upon activation, it triggers a cascade of events, including the phosphorylation and degradation of IκB proteins (inhibitors of NF-κB), which sequester NF-κB in the cytoplasm. Once released, the NF-κB protein complex, comprising subunits such as p65 and p50, translocates to the nucleus. This complex acts as a transcription factor, binding to specific DNA sequences to regulate the expression of genes involved in immune responses and inflammation. In the context of acne, activation of the NF-κB pathway by TLR2 signaling leads to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-12, TNF-α, and IL-8 [23,24]. These cytokines contribute to the recruitment and activation of immune cells, amplifying the localized inflammatory response observed in acne lesions. Recent advances have identified several genes that regulate inflammation in immune cells, keratinocytes, and sebocytes, which have significantly enhanced our understanding of the pathophysiology of acne, where distinct cytokine networks and cellular functions are orchestrated by different cell types [25,26]. In immune cells, innate cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-10 play distinct roles in acne. C. acnes activates the NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome in monocytes, leading to the release of IL-1β and IL-18 [27], while IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, is downregulated in acne patients [28]. The reduction of IL-10 impairs its ability to inhibit macrophage and dendritic cell functions, including antigen presentation and the production of inflammatory mediators such as IL-12, and reactive oxygen species [27,28]. Additionally, C. acnes induces both Th1 and Th17 responses as evidenced by elevated IL-17 and IFN-γ in inflammatory acne lesions [29,30]. Our prior studies demonstrated that C. acnes ribotypes differentially regulate Th17 responses, with acne-associated strains inducing higher IL-17 levels compared to healthy strains [29,31]. Furthermore, C. acnes strains can induce the release of antimicrobial extracellular traps by Th17 cells which help kill bacteria [32]. Interestingly, circadian regulators such as BMAL1 have also been implicated in acne-related inflammation. BMAL1 modulates inflammatory responses in macrophages and keratinocytes, potentially influencing the expression of inflammatory cytokines via the NF-κB/NLRP3 axis [25]. The NLRP3 pathway plays a pivotal role in innate immunity by detecting cellular stress and harmful stimuli. Activation of NLRP3 triggers the assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome, a multiprotein complex that promotes the cleavage and release of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18. Beyond inflammasome activation, the NLRP3 pathway is closely linked to upstream signaling pathways, including NF-κB, which primes NLRP3 by increasing the expression of its components. Collectively, these findings highlight the complex network of genes and signaling pathways, including NF-κB, NLRP3, and associated cytokines that drive the inflammatory processes in acne pathogenesis [25] (Table 1 and Figure 2).

In keratinocytes, several genes and non-coding RNAs contribute to the inflammatory response in acne. MicroRNAs such as miR-146a and miR-143 regulate TLR2 expression and activate the IRAK1/TRAF6/NF-κB and MAPK pathways [33,34]. Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1) and TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) are key proteins in the TLR2 signaling cascade. Upon TLR2 activation by microbial components such as C. acnes, IRAK1 is recruited to the receptor complex and phosphorylated. This activates TRAF6, a ubiquitin ligase, which triggers a cascade of downstream signaling events that ultimately activate the NF-κB pathway. The MAPK pathway is another critical signaling activated by IRAK1 and TRAF6 signaling. The MAPK pathway involves three primary kinase families: ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase), JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase), and p38. In acne, these kinases phosphorylate and activate transcription factors that enhance the expression of genes involved in inflammation, further amplifying the inflammatory response [33,34]. MiR-143 decreases the stability of TLR2 mRNA, reducing TLR2 protein levels and modulating inflammation [33,34]. Furthermore, the circular RNA hsa_circ_0102678 influences the miR-146a/TRAF6/IRAK1 axis to enhance inflammatory responses in keratinocytes [35]. Additional regulators such as TNIP1 upregulate multiple inflammatory pathways, including NF-κB, p38, MAPK, and JNK, contributing to keratinocyte-driven inflammation [36]. Similarly, TNFAIP3 plays a dual regulatory role by modulating both the JNK and NF-κB signaling pathways, leading to altered levels of cytokines and chemokines such as IL-6, CCL5, and IL-8 [37]. The long non-coding RNA H19, when knocked down, inhibits the miR-196a/TLR2/NF-κB axis, highlighting its pro-inflammatory role [38]. PAR-2, another key player, upregulates the IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (three central pro-inflammatory cytokines) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), underscoring its contribution to keratinocyte-mediated inflammation [39] (Table 1 and Figure 2). In sebocytes, TRPV3 expression is elevated in the facial sebaceous glands of acne patients [40]. Mechanistically, TRPV3 enhances TLR2 expression by promoting the transcription factor phosphorylated FOS-like antigen-1, which binds to the TLR2 promoter, leading to TLR2 upregulation and activation of downstream NF-κB signaling pathways [40]. Stimulation of SEB-1 cells with the C. acnes strain HL043PA1 resulted in a significant upregulation of S100A8 expression, while S100A9 levels remained stable. Silencing both S100A8 and S100A9 resulted in a 50% reduction of IL-6 and IL-8 production in C. acnes-exposed sebocytes, indicating the proinflammatory function of S100A8/A9 in sebocytes [26]. Interestingly, the formation of extracellular traps in sebocytes following HL043PA1 treatment was observed [7], a phenomenon previously described by Agak et al. in immune cells such as Th17 cells [32]. This observation expands our understanding by demonstrating that some non-immune cells, such as sebocytes, can also release extracellular traps as part of their defense against C. acnes, suggesting a broader role for these traps in skin immunity (Table 1 and Figure 2). Additionally, S100A8 and S100A9 have been shown to stimulate keratinocyte proliferation via the MAPK pathway suggesting their involvement in hyperkeratinization [31]. These findings indicate that S100A8 and S100A9 not only contribute to inflammation but may also play a pivotal role in linking hyperkeratinization and inflammation [26,41]. This dual role underscores their potential as key mediators in acne (Tables 1, 2, and Figure 2). In our study, we performed a differential analysis of altered signaling pathways, identifying 26 genes with significantly changed expression levels in acne lesions compared to normal skin [11]. We then focused on 10 genes predominantly expressed in myeloid cells and lymphocytes due to their strong association with inflammation. Among these, granulin precursor (GRN) was consistently dysregulated among all six lesional samples compared to non-lesional samples. Further analysis revealed that GRN and its receptor, Sortilin 1 (SORT1), were upregulated in TREM2-expressing macrophages [11]. Treatment with GRN led to increased expression of three central pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including IL-18, CCL5, and CXCL21. These findings suggest that the GRN-SORT1 axis plays a critical role in amplifying the inflammatory response in TREM2 macrophages, potentially exacerbating inflammation in acne lesions [11]. Consistent with our study, GRN was primarily expressed in macrophages across multiple organs, including the brain [42], pancreas [43], and liver [44], indicating its critical role in macrophage function. Further research is needed to explore its contribution to acne formation in vivo.

|

Gene |

Acne model or cell type |

Expression Change |

Mechanism |

|

TLR2 [23] |

Peritoneal macrophage, RAW 264.7 cell, primary human monocyte |

Upregulated |

Receptor for C. acnes and activate NF-κB signaling |

|

IL-17 [30,31] |

Th17 and Th1 cells |

Upregulated |

Promotion of Th17 Cell Differentiation; Induce the expression of three central pro-inflammatory cytokines |

|

IFN-γ [63] |

CD4+ T cells |

Upregulated |

Mediate Th1 cell differentiation and response, activate immune cells including natural killer cell and macrophages, present antigens, and release cytokines including IL-12 [64,65] |

|

IL-10 [24,66] |

PBMCs |

Downregulated |

Inhibit macrophage and dendritic cell functions by downregulating antigen presentation as well as the production of IL-12, chemokines, nitric oxide, reactive oxygen species and co-stimulatory molecules. C. acnes strains associated with healthy skin upregulate IL-10 expression |

|

GRN [11] |

TREM2 macrophage |

Upregulated |

Increase the expression of three central pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-18, CCL5, and CXCL2 |

|

IL-1β [27] |

Primary human monocyte |

Upregulated |

Activate NLRP3 inflammasome |

|

BMAL1 [25] |

C57BL/6 mice, RAW264.7 cell, Primary mouse keratinocyte |

Downregulated |

Inhibit NF-κB/NLRP3 axis |

|

miR-146a [33] |

Primary human keratinocyte |

Upregulated |

Activate the TLR2/IRAK1/TRAF6/NF-κB and MAPK pathways. |

|

miR-143 [34] |

Tlr2−/− mice and NHEK cell |

Upregulated |

Decrease the stability of TLR2 mRNA and then decreased TLR2 protein |

|

hsa_circ_0102678[35] |

Primary human keratinocyte |

Upregulated |

Regulate miR-146a/TRAF6 and IRAK1 axis |

|

TNIP1 [36] |

HPV-KER and NHEK cell |

Upregulated |

Upregulate the NF-κB, p38, MAPK and JNK pathways |

|

TNFAIP3 [37] |

HPV-KER cell |

Upregulated |

Dually regulate JNK and NF-κB signaling |

|

PAR-2 [39] |

HaCaT |

Upregulated |

Regulate the expression of three central pro-inflammatory cytokines, hBD-2, LL-37, MMP-1, -2, -3, -9, and -13 |

|

H19 [38] |

HaCaT cell |

Upregulated |

Regulate the miR-196a/TLR2/NF-κB Axis. |

|

TRPV3 [40] |

Acne mice model and Sebocyte |

Upregulated |

Lead to TLR2 upregulation and downstream NF-κB signaling activation |

|

S100A8 [26] |

Sebocyte |

Upregulated |

Promote the expression level of IL-8 and IL-6 |

|

S100A9 [26] |

Sebocyte |

Unchanged |

|

|

HPK: Human Primary Keratinocyte; NHEK: Normal Human Epidermal Keratinocytes; HPV-KER: Human Papillomavirus-Immortalized Keratinocyte; PBMCs: Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells |

|||

Figure 2: Overview of key genes involved in inflammation and hyperkeratinization in acne. The diagram lists genes from immune cells, keratinocytes, and sebocytes participating in these processes. Each circle represents a cell type, with overlapping regions indicating shared gene contributions. The overlapping circles highlight shared gene involvement across cell types in acne. The middle overlapping light purple area between inflammation (blue) and hyperkeratinization (yellow) demonstrates that genes from sebocytes and keratinocytes contribute to both inflammation and hyperkeratinization. Upregulated, downregulated, and unchanged genes are marked in red, green, and black, respectively.

The Intersection of Hyperkeratinization and Inflammation in Acne

Hyperkeratinization in acne involves an abnormal increase in keratin production within hair follicles, leading to clogged pores that set the stage for comedone formation. This process is triggered by hormonal shifts, especially during adolescence, which increase keratinocyte proliferation and disrupt normal desquamation [45]. As keratin and sebum accumulate within the follicle, they create an occlusive environment that not only obstructs the pore but also traps C. acnes which thrives in lipid-rich conditions [10]. In the context of acne, key signaling pathways, including the MAPK and PI3K/AKT/FoxO1 axes, are implicated in keratinocyte hyperproliferation, which can lead to hyperkeratinization [45]. For example, IGF-1 and IL-8 activate AKT signaling to regulate FoxO1 activity, while downregulation of FoxO1 results in increased keratinocyte proliferation and excessive keratin production, further promoting follicular occlusion [46-48] (Table 2 and Figure 2). Beyond their function in hyperkeratinization, keratinocytes also actively mediate immune signaling [49]. Upon exposure to C. acnes, keratinocytes release three central pro-inflammatory cytokines, signaling immune cells to migrate to the follicle [49]. This immune recruitment promotes inflammation, transforming a non-inflammatory comedone into a papule or pustule [10]. Additionally, keratinocytes produce antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), including LL-37 and β-defensin, which may help counteract C. acnes growth [50]. However, while these AMPs are protective in the skin, they also exacerbate local inflammation through stimulating cytokine/chemokine production and participate in wound healing by promoting keratinocyte migration and proliferation, creating a cycle in which the immune response perpetuates follicular hyperkeratinization and inflammation, highlighting the intricate interplay between these processes [51]. Hyperkeratinization is fundamentally driven by the dysregulation of keratinocyte signaling pathways. Recent research, including our own analysis of published scRNA-seq datasets, identified the IL-13-IL13RA1 axis—a critical component of the type 2 immune pathway—as a key modulator of keratinocyte function in acne [11]. Activation of this pathway disrupts the expression of essential differentiation genes such as KRT16, KRT17, and FLG, leading to impaired keratinocyte differentiation and abnormal keratin accumulation [11]. The IL-13-IL13RA1 axis influences acne through multiple mechanisms. It regulates lipid metabolism in sebocytes [52], impairs skin barrier function by downregulating FLG expression [53], and contributes to tissue remodeling and fibrosis [54]. As IL-13 is secreted by mast cells, NKT cells, T cells, and neutrophils [11], this pathway links immune signaling to hyperkeratinization. These findings suggest that immune polarization towards a type 2 response may drive keratinocyte proliferation and contribute to the pathogenesis of acne lesions.

|

Gene |

Acne model or material used |

Expression Change |

Mechanism |

|

S100A8 [26,41] |

HaCaT cell |

Upregulated |

Promote the inflammation and MAPK pathway |

|

S100A9 [26,41] |

HaCaT cell |

Upregulated |

|

|

IL-8 [24,46] |

HaCaT cell |

Upregulated |

Activate the inflammation and AKT/FOXO1 axis |

|

IGF-1/IGF1-R [47] |

Skin biopsies and NHEK cell |

Upregulated |

Regulate inflammation and Induce proliferation of keratinocyte through PI3K/Akt/FoxO1 |

|

FoxO1 [48,67] |

HPK |

Downregulated |

Regulate inflammation and promote differentiation and apoptosis in HPKs |

|

IL13RA1 [11] |

HaCaT cell |

Upregulated |

The ligand IL-13 can be released by mast cell, NK cell, and regulate KRT17, KRT16, and FLG expression. |

Connecting Acne Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Strategies

Based on our findings, we discuss the potential FDA-approved treatments targeting two key pathways identified in acne pathogenesis. One promising clinical application involves dupilumab, an FDA-approved monoclonal antibody that inhibits IL-13 and IL-4 signaling by blocking the IL-4 receptor alpha subunit. While dupilumab is approved for the treatment of atopic dermatitis [55], asthma [56], and chronic rhinosinusitis [57] with nasal polyps, it holds significant potential for treating inflammatory acne. By targeting IL-13, dupilumab may reduce inflammation, restore skin barrier function, and regulate sebocyte activity, offering a novel approach to mitigating acne pathogenesis through modulation of the IL-13-IL13RA1 axis. Currently, there are no FDA-approved treatments specifically targeting GRN or its receptor SORT1. However, targeting the downstream cytokines regulated by the GRN-SORT1 axis could present a promising therapeutic strategy. The GRN-SORT1 axis influences several pro-inflammatory cytokines, including three central pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-18, CCL5, and CXCL2 [11]. For example, Maraviroc, an FDA-approved CCR5 antagonist for HIV, blocks the receptor for CCL5 [58] and may reduce the chemotactic effects of CCL5 in acne lesions. Similarly, TNF-α inhibitors such as Infliximab, Adalimumab, and Etanercept, widely used in the treatment of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [59], can help reduce inflammation by inhibiting TNF-α signaling. IL-6 receptor antagonists, Tocilizumab and Sarilumab, approved for conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis [60], could also offer potential benefits in reducing inflammation in acne. While these therapies were developed for other inflammatory conditions, they provide a foundation for repurposing existing treatments to target the inflammatory pathways that contribute to acne. Notably, IL-1β inhibitors, such as Anakinra and Canakinumab, have shown promise in treating acne [61]. Existing FDA-approved therapies targeting these cytokines above can offer a potential strategy for treating acne. Future clinical research may further validate their efficacy in acne management.

Conclusion

In summary, our findings highlight the importance of understanding cellular communication within acne lesions and identifying novel markers and dysregulated genes that differentiate healthy and acne-prone skin. We also discussed potential FDA-approved treatments targeting two key pathways involved in acne pathogenesis. These insights reveal critical signaling pathways and offer new therapeutic targets for acne treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceiving and Writing, Original Draft Preparation: MD; Figure Visualization: MD, KF; Review and Editing, as well as providing critical suggestions throughout the study: GWA. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sarowar Jahan MG and Keshvad Hedayatyanfard from UCLA for their valuable discussions. This work was supported by NIH grants R01AR081337 (GWA).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

2. Sánchez-Pellicer P, Navarro-Moratalla L, Núñez-Delegido E, Ruzafa-Costas B, Agüera-Santos J, Navarro-López V. Acne, Microbiome, and Probiotics: The Gut-Skin Axis. Microorganisms. 2022 Jun 27;10(7):1303.

3. Yang X, Li G, Lou P, Zhang M, Yao K, Xiao J, et al. Excessive nucleic acid R-loops induce mitochondria-dependent epithelial cell necroptosis and drive spontaneous intestinal inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024 Jan 2;121(1):e2307395120.

4. Yu G, Wang F, You M, Xu T, Shao C, Liu Y, et al. TCF-1 deficiency influences the composition of intestinal microbiota and enhances susceptibility to colonic inflammation. Protein Cell. 2020 May;11(5):380-86.

5. Deng M, Wu X, Duan X, Xu J, Yang X, Sheng X, et al. Lactobacillus paracasei L9 improves colitis by expanding butyrate-producing bacteria that inhibit the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway. Food Funct. 2021 Nov 1;12(21):10700-13.

6. Zhong Y, Wang F, Meng X, Zhou L. The associations between gut microbiota and inflammatory skin diseases: a bi-directional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front Immunol. 2024 Feb 2;15:1297240.

7. Kheshvadjian AR, Deng M, Qin M, To T, Brewer GM, Odhiambo WO, et al. 462 Trapped in brilliance: Unveiling sebocytes’ antimicrobial repertoire. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2024 Aug 1;144(8):S80.

8. Xu J, Tang Y, Sheng X, Tian Y, Deng M, Du S, et al. Secreted stromal protein ISLR promotes intestinal regeneration by suppressing epithelial Hippo signaling. EMBO J. 2020 Apr 1;39(7):e103255.

9. Kim J. Review of the innate immune response in acne vulgaris: activation of Toll-like receptor 2 in acne triggers inflammatory cytokine responses. Dermatology. 2005;211(3):193-8.

10. Moradi Tuchayi S, Makrantonaki E, Ganceviciene R, Dessinioti C, Feldman SR, Zouboulis CC. Acne vulgaris. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015 Sep 17;1:15029.

11. Deng M, Odhiambo WO, Qin M, To TT, Brewer GM, Kheshvadjian AR, et al. Analysis of intracellular communication reveals consistent gene changes associated with early-stage acne skin. Cell Commun Signal. 2024 Aug 14;22(1):400.

12. Gu W, Huang X, Singh PNP, Li S, Lan Y, Deng M, et al. A MTA2-SATB2 chromatin complex restrains colonic plasticity toward small intestine by retaining HNF4A at colonic chromatin. Nat Commun. 2024 Apr 27;15(1):3595.

13. Wu X, Wang S, Pan Y, Li M, Song M, Zhang H, et al. m6A Reader PRRC2A Promotes Colorectal Cancer Progression via CK1ε-Mediated Activation of WNT and YAP Signaling Pathways. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024 Nov 24:e2406935.

14. Sheng X, Lin Z, Lv C, Shao C, Bi X, Deng M, et al. Cycling Stem Cells Are Radioresistant and Regenerate the Intestine. Cell Rep. 2020 Jul 28;32(4):107952.

15. Yang X, Li G, Tian Y, Wang X, Xu J, Liu R, et al. Identifying the E2F3-MEX3A-KLF4 signaling axis that sustains cancer cells in undifferentiated and proliferative state. Theranostics. 2022 Sep 25;12(16):6865-82.

16. O'Neill AM, Liggins MC, Seidman JS, Do TH, Li F, Cavagnero KJ, et al. Antimicrobial production by perifollicular dermal preadipocytes is essential to the pathophysiology of acne. Sci Transl Med. 2022 Feb 16;14(632):eabh1478.

17. Deng M, Guerrero-Juarez CF, Sheng X, Xu J, Wu X, Yao K, et al. Lepr+ mesenchymal cells sense diet to modulate intestinal stem/progenitor cells via Leptin-Igf1 axis. Cell Res. 2022 Jul;32(7):670-86.

18. Song Y, Guerrero-Juarez CF, Chen Z, Tang Y, Ma X, Lv C, et al. The Msi1-mTOR pathway drives the pathogenesis of mammary and extramammary Paget's disease. Cell Res. 2020 Oct;30(10):854-72.

19. Deng M, Odhiambo WO, Gu Y, Pellegrini M, Modlin RL, Agak GW. 072 Mapping cell communication dynamics in acne: Insights from single-cell and spatial transcriptomics. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2024 Aug 1;144(8):S13.

20. Bi X, Lou P, Song Y, Sheng X, Liu R, Deng M, et al. Msi1 promotes breast cancer metastasis by regulating invadopodia-mediated extracellular matrix degradation via the Timp3-Mmp9 pathway. Oncogene. 2021 Jul;40(29):4832-45.

21. Do TH, Ma F, Andrade PR, Teles R, de Andrade Silva BJ, Hu C, et al. TREM2 macrophages induced by human lipids drive inflammation in acne lesions. Sci Immunol. 2022 Jul 22;7(73):eabo2787.

22. Ma F, Hughes TK, Teles RMB, Andrade PR, de Andrade Silva BJ, Plazyo O, et al. The cellular architecture of the antimicrobial response network in human leprosy granulomas. Nat Immunol. 2021 Jul;22(7):839-50.

23. Kim J, Ochoa MT, Krutzik SR, Takeuchi O, Uematsu S, Legaspi AJ, et al. Activation of toll-like receptor 2 in acne triggers inflammatory cytokine responses. J Immunol. 2002 Aug 1;169(3):1535-41.

24. Suvanprakorn P, Tongyen T, Prakhongcheep O, Laoratthaphong P, Chanvorachote P. Establishment of an Anti-acne Vulgaris Evaluation Method Based on TLR2 and TLR4-mediated Interleukin-8 Production. In Vivo. 2019 Nov-Dec;33(6):1929-34.

25. Li F, Lin L, He Y, Sun G, Dong D, Wu B. BMAL1 regulates Propionibacterium acnes-induced skin inflammation via REV-ERBα in mice. Int J Biol Sci. 2022 Mar 21;18(6):2597-608.

26. Kheshvadjian AR, Qin M, Gilliland SP, Deng M, Odhiambo WO, To T, et al. 448 Silencing the storm: siRNA-mediated knockdown of S100A8/A9 diminishes the inflammatory response in sebocytes exposed to cutibacterium acnes. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2024 Aug 1;144(8):S78.

27. Qin M, Pirouz A, Kim MH, Krutzik SR, Garbán HJ, Kim J. Propionibacterium acnes Induces IL-1β secretion via the NLRP3 inflammasome in human monocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2014 Feb;134(2):381-8.

28. Caillon F, O'Connell M, Eady EA, Jenkins GR, Cove JH, Layton AM, Mountford AP. Interleukin-10 secretion from CD14+ peripheral blood mononuclear cells is downregulated in patients with acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2010 Feb 1;162(2):296-303.

29. Agak GW, Qin M, Nobe J, Kim MH, Krutzik SR, Tristan GR, et al. Propionibacterium acnes Induces an IL-17 Response in Acne Vulgaris that Is Regulated by Vitamin A and Vitamin D. J Invest Dermatol. 2014 Feb;134(2):366-73.

30. Kelhälä HL, Palatsi R, Fyhrquist N, Lehtimäki S, Väyrynen JP, Kallioinen M, et al. IL-17/Th17 pathway is activated in acne lesions. PLoS One. 2014 Aug 25;9(8):e105238.

31. Agak GW, Kao S, Ouyang K, Qin M, Moon D, Butt A, et al. Phenotype and Antimicrobial Activity of Th17 Cells Induced by Propionibacterium acnes Strains Associated with Healthy and Acne Skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2018 Feb;138(2):316-24.

32. Agak GW, Mouton A, Teles RM, Weston T, Morselli M, Andrade PR, et al. Extracellular traps released by antimicrobial TH17 cells contribute to host defense. J Clin Invest. 2021 Jan 19;131(2):e141594.

33. Zeng R, Xu H, Liu Y, Du L, Duan Z, Tong J, He Y, Chen Q, Chen X, Li M. miR-146a Inhibits Biofilm-Derived Cutibacterium acnes-Induced Inflammatory Reactions in Human Keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2019 Dec;139(12):2488-96.e4.

34. Xia X, Li Z, Liu K, Wu Y, Jiang D, Lai Y. Staphylococcal LTA-Induced miR-143 Inhibits Propionibacterium acnes-Mediated Inflammatory Response in Skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2016 Mar;136(3):621-30.

35. Zhou M, Liu Y, Xu H, Chen X, Zheng N, Duan Z, et al. YTHDC1-Modified m6A Methylation of Hsa_circ_0102678 Promotes Keratinocyte Inflammation Induced by Cutibacterium acnes Biofilm through Regulating miR-146a/TRAF6 and IRAK1 Axis. J Innate Immun. 2023;15(1):822-35.

36. Erdei L, Bolla BS, Bozó R, Tax G, Urbán E, Kemény L, et al. TNIP1 Regulates Cutibacterium acnes-Induced Innate Immune Functions in Epidermal Keratinocytes. Front Immunol. 2018 Sep 24;9:2155.

37. Erdei L, Bolla BS, Bozó R, Tax G, Urbán E, Burián K, et al. Tumour Necrosis Factor Alpha-induced Protein 3 Negatively Regulates Cutibacterium acnes-induced Innate Immune Events in Epidermal Keratinocytes. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021 Jan 13;101(1):adv00369.

38. Yang S, Fang F, Yu X, Yang C, Zhang X, Wang L, et al. Knockdown of H19 Inhibits the Pathogenesis of Acne Vulgaris by Targeting the miR-196a/TLR2/NF-κB Axis. Inflammation. 2020 Oct;43(5):1936-47.

39. Lee SE, Kim JM, Jeong SK, Jeon JE, Yoon HJ, Jeong MK, et al. Protease-activated receptor-2 mediates the expression of inflammatory cytokines, antimicrobial peptides, and matrix metalloproteinases in keratinocytes in response to Propionibacterium acnes. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010 Dec;302(10):745-56.

40. Wei Z, Gao M, Liu Y, Zeng R, Liu J, Sun S, et al. TRPV3 promotes sebocyte inflammation via transcriptional modulating TLR2 in acne. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2024 Jun;1870(5):167195.

41. Cao J, Xu M, Zhu L, Xiao S. Viaminate Inhibits Propionibacterium Acnes-induced Abnormal Proliferation and Keratinization of HaCat Cells by Regulating the S100A8/S100A9- MAPK Cascade. Curr Drug Targets. 2023;24(13):1055-65.

42. Baker M, Mackenzie IR, Pickering-Brown SM, Gass J, Rademakers R, Lindholm C, et al. Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature. 2006 Aug 24;442(7105):916-9.

43. Nielsen SR, Quaranta V, Linford A, Emeagi P, Rainer C, Santos A, et al. Macrophage-secreted granulin supports pancreatic cancer metastasis by inducing liver fibrosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2016 May;18(5):549-60.

44. Gan WL, Ren X, Ng VHE, Ng L, Song Y, Tano V, et al. Hepatocyte-macrophage crosstalk via the PGRN-EGFR axis modulates ADAR1-mediated immunity in the liver. Cell Rep. 2024 Jul 23;43(7):114400.

45. Kurokawa I, Danby FW, Ju Q, Wang X, Xiang LF, Xia L, et al. New developments in our understanding of acne pathogenesis and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2009 Oct;18(10):821-32.

46. Yu XQ, Mao JZ, Yang SY, Wang L, Yang CZ, Huang L, et al. Autocrine IL-8 Contributes to Propionibacterium Acnes-induced Proliferation and Differentiation of HaCaT Cells via AKT/FOXO1/ Autophagy. Curr Med Sci. 2024 Oct;44(5):1058-65.

47. Isard O, Knol AC, Ariès MF, Nguyen JM, Khammari A, Castex-Rizzi N, et al. Propionibacterium acnes activates the IGF-1/IGF-1R system in the epidermis and induces keratinocyte proliferation. J Invest Dermatol. 2011 Jan;131(1):59-66.

48. Shi G, Liao PY, Cai XL, Pi XX, Zhang MF, Li SJ, et al. FoxO1 enhances differentiation and apoptosis in human primary keratinocytes. Exp Dermatol. 2018 Nov;27(11):1254-60.

49. Feng Y, Li J, Mo X, Ju Q. Macrophages in acne vulgaris: mediating phagocytosis, inflammation, scar formation, and therapeutic implications. Front Immunol. 2024 Mar 14;15:1355455.

50. Takahashi M, Umehara Y, Yue H, Trujillo-Paez JV, Peng G, Nguyen HLT, et al. The Antimicrobial Peptide Human β-Defensin-3 Accelerates Wound Healing by Promoting Angiogenesis, Cell Migration, and Proliferation Through the FGFR/JAK2/STAT3 Signaling Pathway. Front Immunol. 2021 Sep 14;12:712781.

51. Niyonsaba F, Ushio H, Nakano N, Ng W, Sayama K, Hashimoto K, et al. Antimicrobial peptides human beta-defensins stimulate epidermal keratinocyte migration, proliferation and production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. J Invest Dermatol. 2007 Mar;127(3):594-604.

52. Zhang C, Chinnappan M, Prestwood CA, Edwards M, Artami M, Thompson BM, et al. Interleukins 4 and 13 drive lipid abnormalities in skin cells through regulation of sex steroid hormone synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Sep 21;118(38):e2100749118.

53. Sander N, Stölzl D, Fonfara M, Hartmann J, Harder I, Suhrkamp I, et al. Blockade of interleukin-13 signalling improves skin barrier function and biology in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2024 Aug 14;191(3):344-50.

54. Oh MH, Oh SY, Yu J, Myers AC, Leonard WJ, Liu YJ, et al. IL-13 induces skin fibrosis in atopic dermatitis by thymic stromal lymphopoietin. J Immunol. 2011 Jun 15;186(12):7232-42.

55. Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, Cather JC, Weisman J, Pariser D, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017 Jun 10;389(10086):2287-303.

56. Castro M, Corren J, Pavord ID, Maspero J, Wenzel S, Rabe KF, et al. Dupilumab Efficacy and Safety in Moderate-to-Severe Uncontrolled Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jun 28;378(26):2486-96.

57. Bachert C, Han JK, Desrosiers M, Hellings PW, Amin N, Lee SE, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in patients with severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (LIBERTY NP SINUS-24 and LIBERTY NP SINUS-52): results from two multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2019 Nov 2;394(10209):1638-50.

58. Martin-Blondel G, Brassat D, Bauer J, Lassmann H, Liblau RS. CCR5 blockade for neuroinflammatory diseases--beyond control of HIV. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016 Feb;12(2):95-105.

59. Ascef BO, Almeida MO, Medeiros-Ribeiro AC, Oliveira de Andrade DC, Oliveira Junior HA, de Soárez PC. Therapeutic Equivalence of Biosimilar and Reference Biologic Drugs in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 May 1;6(5):e2315872.

60. den Broeder N, den Broeder AA, Verhoef LM, van den Hoogen FHJ, van der Maas A, van den Bemt BJF. Non-Medical Switching from Tocilizumab to Sarilumab in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients with Low Disease Activity, an Observational Study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2023 Oct;114(4):810-4.

61. Sanz-Cabanillas JL, Gómez-García F, Gómez-Arias PJ, Montilla-López A, Gay-Mimbrera J, Ruano J, et al. Efficacy and safety of anakinra and canakinumab in PSTPIP1-associated inflammatory diseases: a comprehensive scoping review. Front Immunol. 2024 Jan 8;14:1339337.

62. Karlsson M, Zhang C, Méar L, Zhong W, Digre A, Katona B, et al. A single-cell type transcriptomics map of human tissues. Sci Adv. 2021 Jul 28;7(31):eabh2169.

63. Mouser PE, Baker BS, Seaton ED, Chu AC. Propionibacterium acnes-reactive T helper-1 cells in the skin of patients with acne vulgaris. J Invest Dermatol. 2003 Nov;121(5):1226-8.

64. Schroder K, Hertzog PJ, Ravasi T, Hume DA. Interferon-gamma: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J Leukoc Biol. 2004 Feb;75(2):163-89.

65. Vivier E, Raulet DH, Moretta A, Caligiuri MA, Zitvogel L, Lanier LL, et al. Innate or adaptive immunity? The example of natural killer cells. Science. 2011 Jan 7;331(6013):44-9.

66. Yu Y, Champer J, Agak GW, Kao S, Modlin RL, Kim J. Different Propionibacterium acnes Phylotypes Induce Distinct Immune Responses and Express Unique Surface and Secreted Proteomes. J Invest Dermatol. 2016 Nov;136(11):2221-8.

67. Cai C, Liu S, Liu Y, Huang S, Lu S, Liu F, et al. Paeoniflorin mitigates insulin-like growth factor 1-induced lipogenesis and inflammation in human sebocytes by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt/FoxO1 and JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathways. Nat Prod Bioprospect. 2024 Oct 1;14(1):56.