Abstract

The PRDM16 (PRDI-BF1-interacting and RIZ1-homologous domain 16) participates in a range of biological processes including tumorigenesis. The protein regulates gene transcription through intrinsic chromatin-modifying enzymatic activity or by forming complexes with histone modifications or other nuclear proteins. Accumulating evidence indicates that the methyltransferase activity and its methylation status of PRDM16 had been further studied. Significant advances have been made in elucidating the role and underlying molecular mechanisms of methyltransferase activity and its methylation status of PRDM16 in hematologic tumors and solid tumors. This review focus on the advances of PRDM16 in terms of its methyltransferase activity and methylation status in tumors. Meanwhile, we also discuss the future perspectives of PRDM16 methylation.

Keywords

PRDM16, Methyltransferase activity, Methylation status, Malignant tumor

Introduction

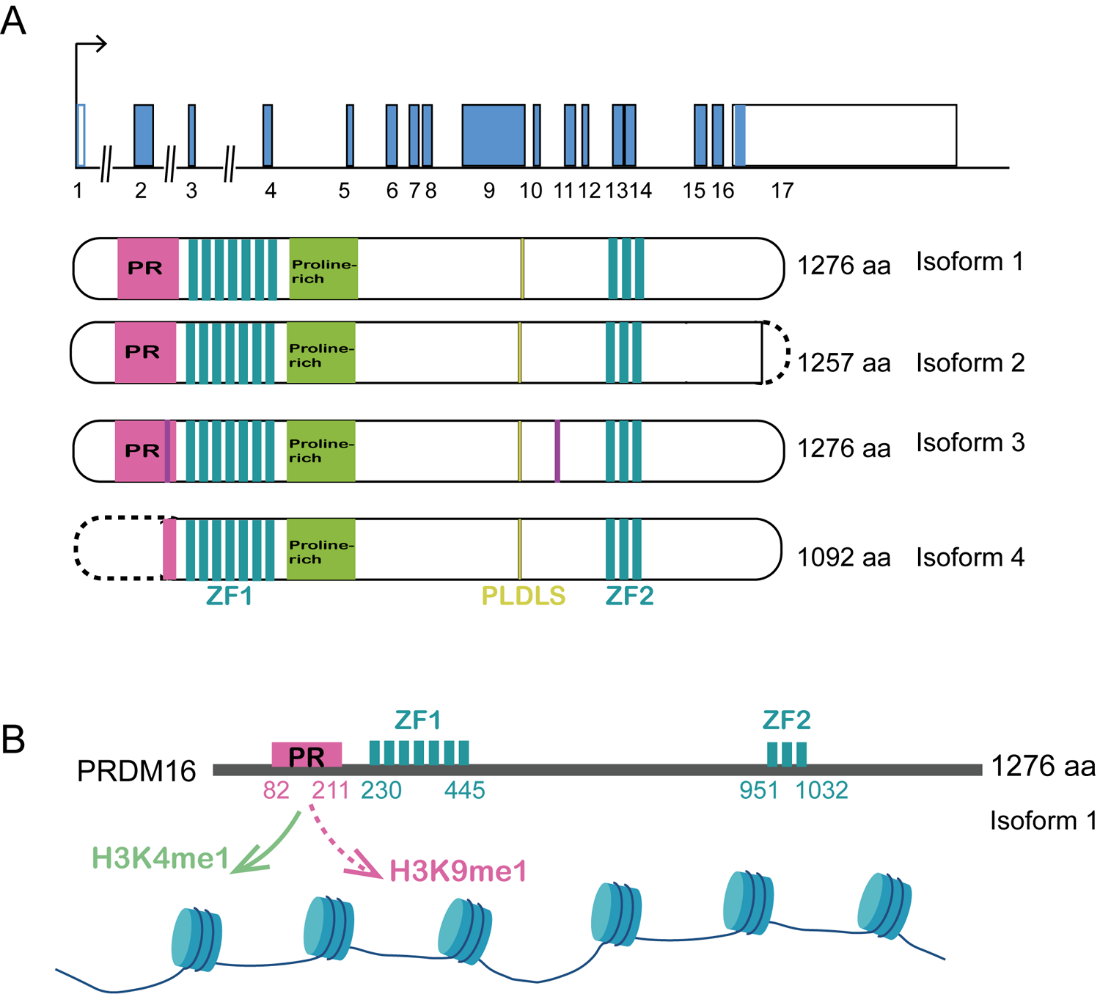

The PRDM protein family consists of 17 members that are structurally defined by the combination of a conserved N-terminal PR (PRDI-BF1 and RIZ1 homology) domain and a variable number of zinc fingers. The PR domain is similar to the SET (suppressor of variegation 3–9, enhancer of zeste, and trithorax) domain found in many histone lysine methyltransferases (HMTs) that function in chromatin-mediated transcriptional regulation [1,2].

These genes regulate a diverse array of biological processes, such as cell proliferation and differentiation, cell cycle progression, and the maintenance of immune cell homeostasis, through epigenetic modulation of gene expression. This regulation occurs via their intrinsic histone methyltransferase (HMTase) activity or through interactions with other chromatin-modifying enzymes. In cancer, tumor-specific dysregulation of PRDM genes results in altered expression patterns, driven by either genetic or epigenetic alterations. Most PRDM genes commonly generate two major molecular isoforms—one containing the PR domain and one lacking it—through alternative splicing or the differential usage of promoters. These isoforms often exert opposing biological functions, particularly in oncogenesis, where an imbalance between them is frequently observed. PRDM proteins are therefore implicated in tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis, and aberrant expression levels are associated with adverse clinical outcomes and poor prognosis. These characteristics underscore their potential as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in cancer, as well as promising targets for novel therapeutic strategies.

Compared with other members of the PRDM family, the role of PRDM16 in tumorigenesis remains a subject of debate. To date, varying methylation levels of PRDM16 and differential methylase activities have been observed not only in hematopoietic malignancies but also in several types of solid tumors though with different and/or conflicting results, which collectively suggest that this gene may possess dual functionalities, acting as both an oncogene and a tumor suppressor gene. Therefore, this review aims to elucidate its involvement in tumor development by integrating an analysis of its functional characteristics, such as its methyltransferase activity and its methylation status.

Molecular Structure of PRDM16

PRDM16 (PRDI-BF1-interacting and RIZ1-homologous domain 16) is a zinc finger protein first identified in 2000 and exhibits significant homology to the MDS1/EVI1 gene (myelodysplastic syndrome 1/ecotropic virus integration site 1) [3,4]. The zinc finger structure that binds specifically to DNA for transcriptional activity and can recognize and bind RNA and protein, which are of the C2H2 type. As a member of PRDM proteins [5,6], the human PRDM16 gene, located on chromosome 11p36.32, contains 17 exons and encodes a zinc finger protein with a positive regulatory (PR) domain, which also contains a proline rich domain (PRR), inhibitory domain (RD), and acidic domain (AD). The PRDM16 gene encodes a protein consisting of 1,276 amino acid residues and shares 64% nucleotide and 63% amino acid sequence similarity with MDS1/EVI1 [7]. Furthermore, it possesses an identical domain structure to that of MDS1/EVI1. Nishikata, et al. isolated a splicing variant of PRDM16 that encodes a shorter isoform, termed sPRDM16. Besides, three transcription start sites were revealed: one located in exon 1 and two within exon 2. Two distinct translation products were detected: a 170 kDa protein corresponding to full-length PRDM16 (flPRDM16) and a 150 kDa protein representing short form of PRDM16 (sPRDM16) (Figure 1A). Additionally, there are four known PRDM16 protein isoforms, among which flPRDM16 and sPRDM16 have been most extensively studied [8]. These two isomers differ in the presence or absence of the PR domain. The longer isoform, flPRDM16, contains the PR domain, whereas the shorter variant, sPRDM16, lacks this domain and acts as a dominant-negative subtype in cancer [9,10]. Importantly, the presence or absence of the PR domain in PRDM16 has been shown to influence its functional roles in disease initiation and progression.

Methyltransferase Activity of the PRDM16 in Hematologic Tumors and Solid Tumors

Recently, PRDMs potentially function as methyltransferases through their PR domain [4,11], given its high homology with the SET domain. The methyltransferase activities of PRDM16 containing the PR domain need to be further studied, with current studies suggesting either H3K4me1 [12] or H3K9me1 [13] specificity (Figure 1B). Zhou et al. firstly discovered that PRDM16 is a highly specific H3 K4 methyltransferase on chromatin and its intrinsic activity is essential for suppressing mixed-lineage-leukemia (MLL1)-rearranged acute leukemia. To determine the substrate specificity of PRDM16 on chromatin, they purified the PR/SET domain of PRDM16 and the PRDM16 mutant (PRDM16mut) carrying two amino acid mutations (C113F and V115G) using an insect cell expression system. To explore substrate specificity, they generated histone mutants in which lysine at positions 4, 9, 27, 36 and 79 was mutated to glutamine (Q), respectively. They found that wild-type PRDM16 cannot methylate H3K4Q in vitro, but can methylate H3 containing other lysine mutations (i.e.K9Q, K27Q, K36Q and K79Q). As a control, PRDM16mut did not show HKMT activity under the same conditions, confirming that H3K4 methylation is caused by the intrinsic activity of the PR domain. To detect the specificity of PRDM16 on nucleosomes, they used recombinant nucleosomes containing wild-type H3, H3K4Q, H3K9Q or H3K27Q mutants as substrates. PRDM16 cannot methylate nucleosomes containing H3K4Q, but has strong activity against nucleosomes composed of H3K9Q or H3K27Q. The PR domain of PRDM16 has intrinsic HKMT activity and is specific to nucleosome H3K4 in vitro. Collectively, PRDM16 is a histone H3K4 methyltransferase on chromatin. Mutation in the N-terminal PR domain of PRDM16 abolishes the intrinsic enzymatic activity of PRDM16 [12]. Prostate cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors in men, and histone methylation has been implicated in its development. Zhu et al. identified PRDM16 as a histone methyltransferase that influences the survival of prostate cancer cells. Their findings indicated that PRDM16 suppresses apoptosis by down-regulating BCL-2 expression and up-regulating BAK expression [14]. To sum up, these findings suggest that methyltransferase activity of PRDM16 plays significant and diverse roles in the pathogenesis of hematologic tumors and solid tumors.

Roles of Hypomethylated PRDM16 in Hematologic Tumors

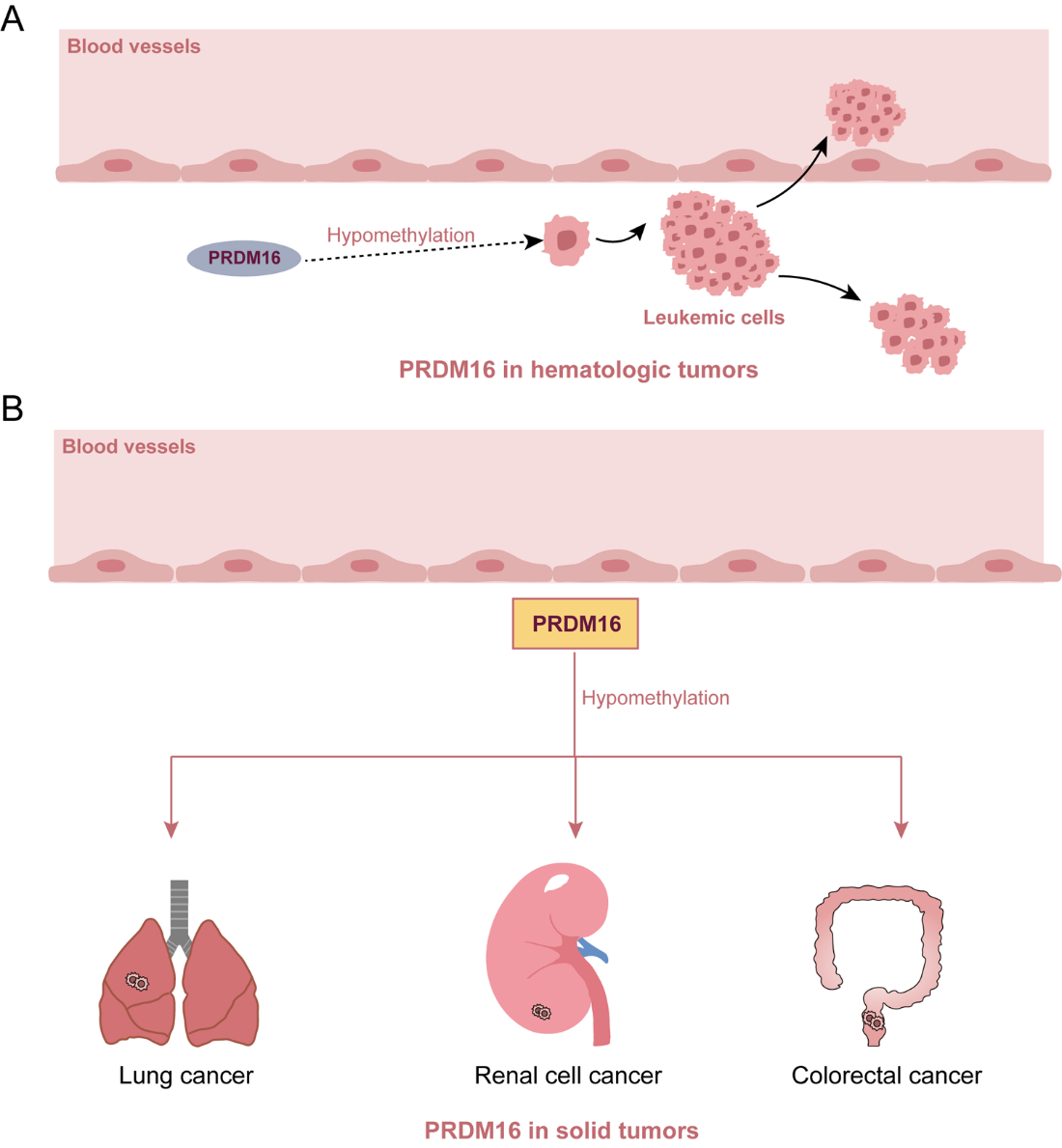

PRDM16 was first reported to be expressed in t(1;3) (p36;q21)-positive leukemia cells and in the normal uterus and fetal kidney but not in the bone marrow or other tissues, indicating that ectopic expression of PRDM16 was specific to t(1;3)(p36;q21)-positive myelodysplastic syndromes/acute myeloid leukemia (MDS/AML) in 2000 [3]. Following the discovery of PRDM16 in AML, researchers have not only focused on its physiological role in lipid metabolism [15–17], but have also increasingly concentrated on elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying PRDM16 methylation status and their association with hematologic tumors development [18,19].Genome-wide DNA methylation analyses of 64 pediatric AML patients demonstrated that significant methylation alterations at 9 CpG sites are associated with PRDM16 expression levels and methyl group abnormalities in AML. These findings suggest that PRDM16 DNA methylation may serve as a promising novel biomarker for pediatric AML [20,21]. Sodium bisulfite sequencing studies have confirmed that PRDM16 exhibits hypomethylation and is frequently expressed during the development of adult T-cell leukemia (ATL), indicating that the aberrant transcription of PRDM16 may be linked to DNA hypomethylation. Further investigations reveal that, the expression of PRDM16 in ATL cells is suppressed through DNA hypermethylation [22]. Collectively, these findings suggest that PRDM16 exhibits hypomethylation and plays significant and diverse roles in the pathogenesis of hematologic tumors (Figure 2A).

Roles of Hypomethylated PRDM16 in Solid Tumors

Evidence indicates that PRDM16 functions as a tumor suppressor based on hypomethylation status in various human malignancies, including lung cancer [23–25], renal cell carcinoma [26], colorectal cancer [27] and pancreatic cancer [28]. For example, studies have demonstrated that the promoter region of PRDM16 undergoes methylation, leading to its downregulation in lung cancer cells. Treatment with demethylating agents has been shown to restore PRDM16 expression and suppress tumor cell proliferation [29]. Reduced or absent PRDM16 mRNA expression has been observed in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tissues, correlating with higher methylation levels in tumor tissues compared to adjacent normal lung tissues [30]. Furthermore, in patients with lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), PRDM16 expression is frequently decreased due to copy number loss and extensive methylation. Patients with low PRDM16 expression exhibit poorer overall survival compared to those with high expression level [31]. A separate study revealed that PRDM16 is epigenetically silenced in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) through promoter hypermethylation. In this study, PRDM16 has been shown to inhibit RCC cell growth both in vitro and in mouse xenograft models by suppressing Semaphorin 5B (SEMA5B) expression, highlighting its role as a tumor suppressor in RCC. This inhibitory function is mediated through PRDM16’s interaction with the transcriptional co-repressor C-terminal binding protein (CTBP1/2) [32], which is essential for the downregulation of SEMA5B and tumor growth [33]. Our study found that methylation level of PRDM16 was associated with CRC and lung metastasis of CRC by DNA methylation sequencing. Furthermore, we identified methylation sites within the promoter region of PRDM16. PRDM16 expression was significantly lower in human CRC tissue samples and dramatically associated with tumor size, T stage, overall survival rates and disease-free survival rates of CRC patients. Down-regulation of PRDM16 significantly promoted proliferation, migration, and invasion of CRC cells by regulating epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) pathway in vitro and in vivo. Decitabine which was a methylate inhibitor increased PRDM16 expression and inhibited CRC progression in vitro and in vivo. Further study showed that PRDM16 interacted with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) in nucleus and upregulated its expression in CRC. Collectively, our study reported that DNA methylation-induced suppression of PRDM16 in CRC metastasis through the PPARγ/EMT pathway [34]. Furthermore, Izquierdo, et al. suggested that the methylation status of PRDM16 may contribute to the initiation and progression of CRC through its involvement in visceral adipose tissue dysfunction [35]. Moreover, PRDM16 has been identified as a candidate gene for pancreatic cancer liquid biopsy methylation markers [36], and may be the most likely candidate methylation marker for pancreatic cancer liquid biopsy in the future. The tumor-suppressive function of PRDM16 provides new insights into the molecular etiology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) [37]. Collectively, these findings underscore that PRDM16 exhibits hypomethylation and plays significant and diverse roles in the pathogenesis of solid tumors (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Roles of PRDM16 in hematologic tumors and solid tumors.

Future Perspectives

Studies utilizing cellular and animal models have demonstrated that PRDM16 may exert methyltransferase activity. As a member of the PRDM family, PRDM16 has received relatively limited attention regarding its methyltransferase function given the high homology between the PR domain of PRDM proteins and the SET domain. Further investigation is warranted to confirm its methyltransferase capabilities and to identify potential methylation sites. Furthermore, at present, only a few articles have identified the activity of PRDM16 as a methyltransferase, but there are no reports on the mechanism by which PRDM16 acts as a methyltransferase to affect tumor progression. In addition, research on the methylation status of PRDM16 has remained at the stage of identifying the DNA methylation status of PRDM16, and there are few articles exploring the mechanism of DNA methylation of PRDM16. Additionally, studies examining how methylation status influence PRDM16 functions, such as its roles in adipocyte differentiation, immune regulation, and tumor proliferation-are currently scarce and merit further exploration.

Furthermore, it has been reported that the tumor suppressor miR-101 could reverse the PRDM16 hypomethylation status thus suppressing its expression through direct epigenetic regulation, finally leading to mitochondrial disruption and apoptosis. After that, few non-coding RNAs have been reported to be involved in the DNA methylation process of PRDM16 [38,39]. Additional research is necessary to determine whether the methylation status of PRDM16 is predominantly regulated at the transcriptional, translational, or post-translational level.

Moreover, it was analyzed systematically that PRDM16 was the m6A RNA methylation-related gene in liver hepatocellular carcinoma, including the expression, interaction, function, and prognostic values, which provided an important theoretical basis for PRDM16 m6A RNA methylation in liver cancer [40]. Subsequently, additional research is necessary to determine whether the RNA methylation level of PRDM16 is related to the tumorigenesis of solid tumor.

Credit Author Statement

WY, WYT drafted the manuscript. HA revised the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statements

None declared.

References

2. Fog CK, Galli GG, Lund AH. PRDM proteins: important players in differentiation and disease. Bioessays. 2012 Jan;34(1):50–60.

3. Mochizuki N, Shimizu S, Nagasawa T, Tanaka H, Taniwaki M, Yokota J, et al. A novel gene, MEL1, mapped to 1p36.3 is highly homologous to the MDS1/EVI1 gene and is transcriptionally activated in t(1;3)(p36;q21)-positive leukemia cells. Blood. 2000 Nov 1;96(9):3209–14.

4. Di Tullio F, Schwarz M, Zorgati H, Mzoughi S, Guccione E. The duality of PRDM proteins: epigenetic and structural perspectives. FEBS J. 2022 Mar;289(5):1256–1275.

5. Sorrentino A, Federico A, Rienzo M, Gazzerro P, Bifulco M, Ciccodicola A, et al. PR/SET Domain Family and Cancer: Novel Insights from the Cancer Genome Atlas. Int J Mol Sci. 2018 Oct 19;19(10):3250.

6. Mzoughi S, Tan YX, Low D, Guccione E. The role of PRDMs in cancer: one family, two sides. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2016 Feb;36:83–91.

7. Lahortiga I, Agirre X, Belloni E, Vázquez I, Larrayoz MJ, Gasparini P, et al. Molecular characterization of a t(1;3)(p36;q21) in a patient with MDS. MEL1 is widely expressed in normal tissues, including bone marrow, and it is not overexpressed in the t(1;3) cells. Oncogene. 2004 Jan 8;23(1):311–6.

8. Corrigan DJ, Luchsinger LL, Justino de Almeida M, Williams LJ, Strikoudis A, et al. PRDM16 isoforms differentially regulate normal and leukemic hematopoiesis and inflammatory gene signature. J Clin Invest. 2018 Aug 1;128(8):3250–64.

9. Dong S, Chen J. SUMOylation of sPRDM16 promotes the progression of acute myeloid leukemia. BMC Cancer. 2015 Nov 11;15:893.

10. Shing DC, Trubia M, Marchesi F, Radaelli E, Belloni E, Tapinassi C, et al. Overexpression of sPRDM16 coupled with loss of p53 induces myeloid leukemias in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007 Dec;117(12):3696–707.

11. Di Zazzo E, De Rosa C, Abbondanza C, Moncharmont B. PRDM Proteins: Molecular Mechanisms in Signal Transduction and Transcriptional Regulation. Biology (Basel). 2013 Jan 14;2(1):107–41.

12. Zhou B, Wang J, Lee SY, Xiong J, Bhanu N, Guo Q, et al. PRDM16 Suppresses MLL1r Leukemia via Intrinsic Histone Methyltransferase Activity. Mol Cell. 2016 Apr 21;62(2):222–36.

13. Pinheiro I, Margueron R, Shukeir N, Eisold M, Fritzsch C, Richter FM, et al. Prdm3 and Prdm16 are H3K9me1 methyltransferases required for mammalian heterochromatin integrity. Cell. 2012 Aug 31;150(5):948–60.

14. Zhu S, Xu Y, Song M, Chen G, Wang H, Zhao Y, et al. PRDM16 is associated with evasion of apoptosis by prostatic cancer cells according to RNA interference screening. Mol Med Rep. 2016 Oct;14(4):3357–61.

15. Ma QX, Zhu WY, Lu XC, Jiang D, Xu F, Li JT, et al. BCAA-BCKA axis regulates WAT browning through acetylation of PRDM16. Nat Metab. 2022 Jan;4(1):106–22.

16. Seale P, Kajimura S, Yang W, Chin S, Rohas LM, Uldry M, et al. Transcriptional control of brown fat determination by PRDM16. Cell Metab. 2007 Jul;6(1):38–54.

17. Gu T, Xu G, Jiang C, Hou L, Wu Z, Wang C. PRDM16 Represses the Pig White Lipogenesis through Promoting Lipolysis Activity. Biomed Res Int. 2019 Jun 13;2019:1969413.

18. Yu H, Neale G, Zhang H, Lee HM, Ma Z, Zhou S, et al. Downregulation of Prdm16 mRNA is a specific antileukemic mechanism during HOXB4-mediated HSC expansion in vivo. Blood. 2014 Sep 11;124(11):1737–47.

19. Yamato G, Yamaguchi H, Handa H, Shiba N, Kawamura M, Wakita S, et al. Clinical features and prognostic impact of PRDM16 expression in adult acute myeloid leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2017 Nov;56(11):800–9.

20. Yamato G, Kawai T, Shiba N, Ikeda J, Hara Y, Ohki K, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 2022 Jun 14;6(11):3207–19.

21. Sonnet M, Claus R, Becker N, Zucknick M, Petersen J, Lipka DB, et al. Early aberrant DNA methylation events in a mouse model of acute myeloid leukemia. Genome Med. 2014 Apr 30;6(4):34.

22. Yoshida M, Nosaka K, Yasunaga J, Nishikata I, Morishita K, Matsuoka M. Aberrant expression of the MEL1S gene identified in association with hypomethylation in adult T-cell leukemia cells. Blood. 2004 Apr 1;103(7):2753–60.

23. Fei LR, Huang WJ, Wang Y, Lei L, Li ZH, Zheng YW, et al. PRDM16 functions as a suppressor of lung adenocarcinoma metastasis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019 Jan 25;38(1):35.

24. Li M, Ren H, Zhang Y, Liu N, Fan M, Wang K, et al. MECOM/PRDM3 and PRDM16 Serve as Prognostic-Related Biomarkers and Are Correlated With Immune Cell Infiltration in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Front Oncol. 2022 Jan 31;12:772686.

25. Fan M, Li M, Zhou J, Li A, Sun Y, Shi P, et al. Clinical value of serum PRDM16 in early diagnosis and prognosis assessment of lung adenocarcinoma. Mol Biol Rep. 2025 Feb 12;52(1):225.

26. Yan C, Wang P, Zhao C, Yin G, Meng X, Li L, et al. Long Noncoding RNA MAGI2-AS3 Represses Cell Progression in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma by Modulating the miR-629-5p/PRDM16 Axis. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2023;33(7):43–56.

27. Hu HF, Han L, Fu JY, He X, Tan JF, Chen QP, et al. LINC00982-encoded protein PRDM16-DT regulates CHEK2 splicing to suppress colorectal cancer metastasis and chemoresistance. Theranostics. 2024 May 27;14(8):3317–38.

28. Hurwitz E, Parajuli P, Ozkan S, Prunier C, Nguyen TL, Campbell D, et al. Antagonism between Prdm16 and Smad4 specifies the trajectory and progression of pancreatic cancer. J Cell Biol. 2023 Apr 3;222(4):e202203036.

29. Tan SX, Hu RC, Liu JJ, Tan YL, Liu WE. Methylation of PRDM2, PRDM5 and PRDM16 genes in lung cancer cells. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014 Apr 15;7(5):2305–11.

30. Tan SX, Hu RC, Xia Q, Tan YL, Liu JJ, Gan GX, et al. The methylation profiles of PRDM promoters in non-small cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2018 May 22;11:2991–3002.

31. Lv W, Yu X, Li W, Feng N, Feng T, Wang Y, et al. Low expression of LINC00982 and PRDM16 is associated with altered gene expression, damaged pathways and poor survival in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2018 Nov;40(5):2698–2709.

32. Kajimura S, Seale P, Tomaru T, Erdjument-Bromage H, Cooper MP, Ruas JL, et al. Regulation of the brown and white fat gene programs through a PRDM16/CtBP transcriptional complex. Genes Dev. 2008 May 15;22(10):1397–409.

33. Kundu A, Nam H, Shelar S, Chandrashekar DS, Brinkley G, Karki S, et al. PRDM16 suppresses HIF-targeted gene expression in kidney cancer. J Exp Med. 2020 Jun 1;217(6):e20191005.

34. Wang Y, Zheng S, Gao H, Wang Y, Chen Y, Han A. DNA methylation-induced suppression of PRDM16 in colorectal cancer metastasis through the PPARγ/EMT pathway. Cell Signal. 2025 Mar;127:111634.

35. Izquierdo AG, Boughanem H, Diaz-Lagares A, Arranz-Salas I, Esteller M, Tinahones FJ, et al. DNA methylome in visceral adipose tissue can discriminate patients with and without colorectal cancer. Epigenetics. 2022 Jun;17(6):665–76.

36. Wang H, Yin F, Yuan F, Men Y, Deng M, Liu Y, et al. Pancreatic cancer differential methylation atlas in blood, peri-carcinomatous and diseased tissue. Transl Cancer Res. 2020 Feb;9(2):421–31.

37. Shi Q, Song G, Song L, Wang Y, Ma J, Zhang L, et al. Unravelling the function of prdm16 in human tumours: A comparative analysis of haematologic and solid tumours. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024 Sep;178:117281.

38. Lei Q, Liu X, Fu H, Sun Y, Wang L, Xu G, et al. miR-101 reverses hypomethylation of the PRDM16 promoter to disrupt mitochondrial function in astrocytoma cells. Oncotarget. 2016 Jan 26;7(4):5007–22.

39. Lin C, He X, Chen X, Liu L, Guan H, Xiao H, et al. miR-1275 Inhibits Human Omental Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Differentiation Toward the Beige Phenotype via PRDM16. Stem Cells Dev. 2022 Dec;31(23-24):799–809.

40. Li Y, Qi D, Zhu B, Ye X. Analysis of m6A RNA Methylation-Related Genes in Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Their Correlation with Survival. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Feb 2;22(3):1474.