Mechanism of Sweat Secretion in Sweat Glands

Sweat, an exocrine fluid secreted (sweat gland tissue of the eccrine and apocrine glands) by skin has an indispensable function for regulating body temperature and skin hydration [1]. The eccrine gland performs 90% of sweat secretion and secretory fluid of eccrine glands consists of 99% water and 1% inorganic substances. Sweat secretion is stimulated by increased body temperature and stress, contributing to skin homeostasis [2]. Hyperhidrosis and anhidrosis are caused by abnormalities in sweat secretion mechanism. Reduced sweat secretion is known to cause not only hyperthermia and heatstroke, but also severe skin conditions such as pruritus and erythema due to dry skin, which significantly reduce patient’s quality of life [3]. Not knowing the exact cause and underlying mechanisms remaining a mystery, it is thought to be triggered in part by neurological and other conditions such as autonomic dysregulation and medications [4]. Moreover, there is a lack of appropriate treatment for anhidrosis, anticholinergic drugs and surgery are available for controlling hyperhidrosis [5,6].

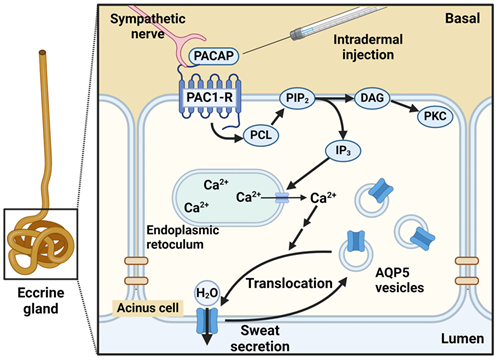

Previous studies have shown acetylcholine (ACh) and noradrenaline (NA) as main neurotransmitters in regulating sweat secretion in sweat glands. These neurotransmitters are thought to act on muscarinic receptor M3-R and adrenergic receptor α1-R expressed in sweat gland cells, thereby increasing intracellular Ca2+, enhancing translocation of Aquaporin 5 (AQP5) from cytosol to plasma membrane, and promoting sweat secretion [7-10]. Store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) mechanisms are known to be involved in the increase of intracellular Ca2+ concentrations [11]. The SOCE is important for increasing intracellular Ca2+ concentrations in the sweat gland, as a stimulation of receptors leads to activation of phospholipase C and generation of inositol trisphosphate (IP3), opening Ca2+ channels in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane releasing Ca2+ into cytosol [12]. Furthermore, decreasing Ca2+ concentration in the ER causes dissociation of Ca2+ from the EF hand motif, which activates stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM 1) and STIM 2 at the ER membrane. The activated STIM stimulates the calcium release-activated calcium (CRAC) channel, resulting in an increase of the intracellular Ca2+ [13].

Increasing intracellular Ca2+ concentrations are reported to promote fluid secretion in various organs via calcium-dependent chloride channels (CaCC) [14,15]. In sweat glands, an influx of Cl- by the CaCC Anoctamin (ANO1) or transmembrane member 16A (TMEM16A) has also been reported in human sweat gland cells, which may act on sweat secretion [16]. Other possible mechanisms of sweat secretion involve bioactive peptides such as galanin, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP), which are non-noradrenergic, non-cholinergic transmitters (NANCs) [17]. Sweat secretion can also be triggered by an increase in intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) [18].

The Function of Aquaporin in the Secretary Gland

Aquaporins are a family of water channels that dynamically and tightly regulate water making up to about 60% of human body. Humans have 13 subtypes of aquaporins, and different tissues express different aquaporins; e.g., AQP1 is expressed in brain, kidney, eye, lung and muscle, AQP2 in renal collecting ducts and AQP4 in astrocytes of central nervous system, skeletal muscle and digestive tract [19]. Aquaporins also play an important role in water secretion in exocrine tissues. AQP5 is involved in production of exocrine secretions in sweat gland, salivary gland, lacrimal gland and lung [20]. AQP5 is an important factor in sweat secretion by sweat gland and is highly expressed in secretory cells of glandular tufts. Sweating secretion with pilocarpine is significantly reduced in AQP5 KO mice [21]. Various pathways have been reported for the activation of AQP5, including intracellular Ca2+ concentration and phosphorylation of AQP5 by the cAMP/PKA pathway [22].

AQP5 is expressed in several exocrine glands, such as salivary and lacrimal gland, and is significantly involved in exocrine actions in humans [23,24]. In particular, AQP5 is thought to be involved in sweat secretion by sweat gland, however, many pathways for AQP5 activation remain unknown [21,25]. A pathway for AQP5 activation has been reported in mouse salivary gland, where AQP5 functions as a water channel by translocating to plasma membrane upon external stimulation [26-28]. In a previous histological study, ANO1, which is activated by increased intracellular Ca2+ concentrations, co-localizes with AQP5 in apical region of mouse sweat glands and is involved in translocation of AQP5 to plasma membrane [8]. A23187, a calcium ionophore activated by increased intracellular Ca2+ concentrations in mouse salivary gland, is involved in translocation of AQP5 to plasma membrane [26]. However, translocation of AQP5 is often not understood and factors other than Ca2+ may be involved.

Description of the PACAP Molecule: An Overview of This Peptide and Its Receptor

PACAP was isolated and identified on the basis of its ability to activate adenylate cyclase in anterior pituitary cells from hypothalamus of sheep brain in 1989 [29,30]. Bioactive peptide PACAP consists of 27 (PACAP27) or 38 (PACAP38) amino acid residues, with almost equivalent physiological effects. PACAP belongs to VIP/secretin/glucagon family, and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and PACAP27 share a high homology (70%). PACAP has three receptors (-R), PAC1-R, VPAC1-R and VPAC2-R, with a particularly high affinity for PAC1 receptor (PAC1-R) (1000-fold higher than other two). Tissue distribution of PACAP and PACAP receptors and in vitro and in vivo physiological and pharmacological studies have revealed several physiological roles for PACAP. These include glucose-dependent stimulation of insulin secretion in pancreatic islets of Langerhans B cells, pain modulation, immunosuppression, protection against ischemic neuronal cell death and neuroregeneration [31].

Recently, PACAP action on tissues such as lacrimal, sweat, and salivary glands to promote exocrine gland secretion was shown. PAC1-R is abundant in duct and adenocytes (column cells) of two major salivary glands (parotid and submandibular). PACAP significantly increased salivation when administered into nasal cavity of mice [32]. As atropine, which has an anticholinergic effect, did not inhibit salivary stimulating effect of PACAP, a novel salivary secretion mechanism downstream of PACAP is implied [32]. The PACAP gene-deficient mice are shown to develop corneal damage resembling corneal xerosis (dry eye). A novel function of PACAP in promoting lacrimal fluid secretion, mediated by its action on PAC1-R in lacrimal gland, phosphorylating AQP5 via activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway and increasing translocation of AQP5 from cytosol to plasma membrane is identified [33]. Thus, PACAP may help in the development of therapeutic agents for dry eye disease [33].

The Mechanism of Sweat Secretion by PACAP

In mouse sweat gland, PACAP is present in ganglia near sweat gland tissue, and PAC1-R is expressed in adenocytes of the sweat gland secretory cells as shown with immunohistological analysis [34]. Specific inhibitors of PAC1-R suppressed the sweat-secreting effects of PACAP in mice [34]. Furthermore, we found the addition of PACAP38 to NCL-SG3 cells, immortalized human eccrine gland cells, transiently increased intracellular Ca2+ concentration in a cAMP-independent manner. The increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration induced by PACAP38 was suppressed by the simultaneous addition of a PAC1R antagonist, suggesting PAC1-R involvement in increasing intracellular Ca2+ concentration through PACAP38. Furthermore, it was reported that PACAP38 transiently translocates localization of AQP5 to the plasma membrane from the cytosol in NCL-SG3 cells by confocal laser microscopy [35]. The function of PACAP in eccrine sweat glands was elucidated in an in vivo study using PAC1R KO mice. The AQP5-containing vesicles were observed in secretory cells of mouse eccrine glands and that intradermal administration of PACAP transferred AQP5 from cytosol to the luminal side [36]. Additionally, experiments with skin tissue post-PACAP administration using DNA microarrays revealed increased expression levels of four genes (Ptgs2, Kcnn2, Cacna1s and Chrna1) with known involvement in sweat secretion in wild type (WT) mice treated with PACAP. Inflammatory markers also increased in PAC1R KO mice compared to WT mice, suggesting that PACAP may have an anti-inflammatory function in the skin [36]. As inflammation caused by TNF-α and NF-κB suppresses AQP5 expression, it can be suggested that inflammation may affect sweat secretion [24].

Figure 1: Schematic intracellular signaling mechanism of PACAP in eccrine sweat secretion. Created with BioRender.

Possibility of Preventing and Treating Skin Dryness by Utilizing the Sweat Secretion Promoting Effect of PACAP and PAC1-R Agonists

We have shown that PACAP has a PAC1-R-mediated mechanism to promote sweat secretion. Recent studies have also suggested that PACAP may also inhibit chronic dermatitis, suggesting that PACAP may be used as a multifunctional skin protection agent with both sweat secretion and skin inflammation inhibitory effects. Nevertheless, PACAP is a peptide and numerous challenges (stability and skin transfer) remain for it to be uses as a drug [37,38]. Therefore, designing PAC1-R agonists is essential in drug development for the prevention and treatment of dry skin disease.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly funded by JSPS KAKENHI [Grant Numbers JP20K20392, JP22H03178].

References

2. Baker LB. Physiology of sweat gland function: The roles of sweating and sweat composition in human health. Temperature (Austin). 2019;6(3):211-59.

3. Lofgren SM,Warshaw EM. Dyshidrosis: Epidemiology, Clinical Characteristics, and Therapy. Dermatitis. 2006;17(4):165-81.

4. Wohlrab J, Bechara FG, Schick C,Naumann M. Hyperhidrosis: A Central Nervous Dysfunction of Sweat Secretion. Dermatology and Therapy. 2023;13(2):453-63.

5. Arora G, Kassir M, Patil A, Sadeghi P, Gold MH, Adatto M, et al. Treatment of Axillary hyperhidrosis. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21(1):62-70.

6. Chia KY,Tey HL. Approach to hypohidrosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(7):799-804.

7. Hu Y, Converse C, Lyons MC,Hsu WH. Neural control of sweat secretion: a review. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(6):1246-56.

8. Inoue R, Sohara E, Rai T, Satoh T, Yokozeki H, Sasaki S, et al. Immunolocalization and translocation of aquaporin-5 water channel in sweat glands. J Dermatol Sci. 2013;70(1):26-33.

9. Klar J, Hisatsune C, Baig SM, Tariq M, Johansson AC, Rasool M, et al. Abolished InsP3R2 function inhibits sweat secretion in both humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(11):4773-80.

10. Cui CY,Schlessinger D. Eccrine sweat gland development and sweat secretion. Exp Dermatol. 2015;24(9):644-50.

11. Prakriya M,Lewis RS. Store-Operated Calcium Channels. Physiol Rev. 2015;95(4):1383-436.

12. Alzayady KJ, Wang L, Chandrasekhar R, Wagner LE, 2nd, Van Petegem F,Yule DI. Defining the stoichiometry of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate binding required to initiate Ca2+ release. Sci Signal. 2016;9(422):ra35.

13. Feske S. CRAC channelopathies. Pflugers Arch. 2010;460(2):417-35.

14. Ertongur-Fauth T, Hochheimer A, Buescher JM, Rapprich S,Krohn M. A novel TMEM16A splice variant lacking the dimerization domain contributes to calcium-activated chloride secretion in human sweat gland epithelial cells. Exp Dermatol. 2014;23(11):825-31.

15. Servetnyk Z,Roomans GM. Chloride transport in NCL-SG3 sweat gland cells: channels involved. Exp Mol Pathol. 2007;83(1):47-53.

16. Concepcion AR, Vaeth M, Wagner LEn, Eckstein M, Hecht L, Yang J, et al. Store-operated Ca2+ entry regulates Ca2+-activated chloride channels and eccrine sweat gland function. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(11):4303-18.

17. Bovell DL, Holub BS, Odusanwo O, Brodowicz B, Rauch I, Kofler B, et al. Galanin is a modulator of eccrine sweat gland secretion. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22(2):141-3.

18. Sato K,Sato F. Effect of VIP on sweat secretion and cAMP accumulation in isolated simian eccrine glands. Am J Physiol. 1987;253(2):935-41.

19. Markou A, Unger L, Abir-Awan M, Saadallah A, Halsey A, Balklava Z, et al. Molecular mechanisms governing aquaporin relocalisation. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2022;1864(4):183853.

20. D'Agostino C, Parisis D, Chivasso C, Hajiabbas M, Soyfoo MS,Delporte C. Aquaporin-5 Dynamic Regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(3):1889.

21. Nejsum LN, Kwon TH, Jensen UB, Fumagalli O, Frokiaer J, Krane CM, et al. Functional requirement of aquaporin-5 in plasma membranes of sweat glands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(1):511-16.

22. Kitchen P, Oberg F, Sjohamn J, Hedfalk K, Bill RM, Conner AC, et al. Plasma membrane abundance of human aquaporin 5 is dynamically regulated by multiple pathways. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0143027.

23. Direito I, Madeira A, Brito MA,Soveral G. Aquaporin-5: from structure to function and dysfunction in cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(8):1623-40.

24. Verkman AS,Mitra AK. Structure and function of aquaporin water channels. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;278(1):F13-28.

25. Inoue R. New Findings on the Mechanism of Perspiration Including Aquaporin-5 Water Channel. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2016;51:11-21.

26. Ishikawa Y, Yuan Z, Inoue N, Skowronski MT, Nakae Y, Shono M, et al. Identification of AQP5 in lipid rafts and its translocation to apical membranes by activation of M3 mAChRs in interlobular ducts of rat parotid gland. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289(5):C1303-11.

27. Ishikawa Y, Cho G, Yuan Z, Inoue N,Nakae Y. Aquaporin-5 water channel in lipid rafts of rat parotid glands. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758(8):1053-60.

28. Ishikawa Y, Eguchi T, Skowronski MT,Ishida H. Acetylcholine acts on M3 muscarinic receptors and induces the translocation of aquaporin5 water channel via cytosolic Ca2+ elevation in rat parotid glands. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;245(3):835-40.

29. Miyata A, Arimura A, Dahl RR, Minamino N, Uehara A, Jiang L, et al. Isolation of a novel 38 residue-hypothalamic polypeptide which stimulates adenylate cyclase in pituitary cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;164(1):567-74.

30. Miyata A, Jiang L, Dahl RD, Kitada C, Kubo K, Fujino M, et al. Isolation of a neuropeptide corresponding to the N-terminal 27 residues of the pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide with 38 residues (PACAP38). Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;170(2):643-48.

31. Vaudry D, Falluel-Morel A, Bourgault S, Basille M, Burel D, Wurtz O, et al. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and its receptors: 20 years after the discovery. Pharmacol Rev. 2009;61(3):283-357.

32. Matoba Y, Nonaka N, Takagi Y, Imamura E, Narukawa M, Nakamachi T, et al. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide enhances saliva secretion via direct binding to PACAP receptors of major salivary glands in mice. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2016;299(9):1293-9.

33. Nakamachi T, Ohtaki H, Seki T, Yofu S, Kagami N, Hashimoto H, et al. PACAP suppresses dry eye signs by stimulating tear secretion. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12034.

34. Sasaki S, Watanabe J, Ohtaki H, Matsumoto M, Murai N, Nakamachi T, et al. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide promotes eccrine gland sweat secretion. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(2):413-22.

35. Yamashita M, Takenoya F, Hirabayashi T, Shibato J, Rakwal R, Takasaki I, et al. Effect of PACAP on sweat secretion by immortalized human sweat gland cells. Peptides. 2021;146:170647.

36. Yamashita M, Shibato J, Rakwal R, Nonaka N, Hirabayashi T, Harvey BJ, et al. Molecular and Physiological Functions of PACAP in Sweat Secretion. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(5):4572.

37. Kovacs AK, Atlasz T, Werling D, Szabo E, Reglodi D,Toth GK. Stability Test of PACAP in Eye Drops. J Mol Neurosci. 2021;71(8):1567-74.

38. Zhao L, Chen J, Bai B, Song G, Zhang J, Yu H, et al. Topical drug delivery strategies for enhancing drug effectiveness by skin barriers, drug delivery systems and individualized dosing. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1333986.