Abstract

Myocardial work is a new tool in echocardiography that incorporates after load to left ventricular strain, although it is a promising technique validated by invasive methods also presents some disadvantages related to the method or the complexity of the clinical case that we should know.

The objectives of this review are to mention the technical aspects of the method and the clinical application in different pathologies.

Keywords

Cardiac resynchronization therapy, Cardiomyopathies, Echocardiography, Global longitudinal strain, Athlete´s heart, Myocardial work, Transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Introduction

Left ventricular performance has traditionally been evaluated by calculating ejection fraction (LVEF), however, the estimation of this by two-dimensional echocardiogram is subject to several limitations. On the other hand, speckle-tracking echocardiography (STE) with global longitudinal deformation (GLS) is increasingly used to assess even subtle myocardial dysfunction, although it is a well-validated method for clinical utility in the assessment of cardiac diseases, it remains limited by its load dependency [1,2]. In patients with significantly increased afterload, GLS may decrease and lead to false conclusions about left ventricular (LV) contractility. However, this load-dependent limitation of GLS can be improved by measuring myocardial work (MW), which considers both GLS and the afterload exerted on the LV [3]. In recent years, a new echocardiographic tool called MW, which measures the pressure-strain loop of LV through a non-invasive method, is being used. This last method is based on the great work of Otto Frank who in 1985 analyzed the hemodynamics of the LV invasively through a pressure-volume loop incorporating the interaction of preload, afterload, and contractility to the analysis of LV performance. The area under the LV pressure-volume curve reflects myocardial work and myocardial oxygen consumption, however, due to its invasive nature, it has never been implemented in daily clinical practice.

Recently, Russel et al. established a method to non-invasively evaluate MW by obtaining pressure-strain loops of the LV, for this purpose they estimated left ventricular pressure (LVP) and GLS obtained by STE. This study found a high correlation between LV pressure-volume and estimated LV pressure-strain loop in animals and patients with left bundle branch block, dyssynchrony, or ischemic heart disease [4]. The development of this model opens the door to the study of LV performance with techniques that, unlike GLS and LVEF, less depend on afterload with possible multiple applications in clinical practice.

Myocardial Work Methodology

Left ventricular MW is a novel, speckle-tracking-based method that evaluates LV work and is estimated by employing brachial arterial blood pressure and left ventricular GLS. Specific software is necessary to assess non-invasive MW.

The initial step of the acquisition is to obtain the transthoracic apical views (long-axis views of 2, 3, and 4 cameras) for the analysis of the GLS, acquired with a frame rate between 50-80 frames/s, adequate quality to visualize the edges of the myocardium and the width of the region of interest (ROI) must be adjusted to cover the entire myocardium and not the pericardium is included. Automated imagery is used to calculate GLS in apical views.

The next step in MW acquisition is determining the timing of the valvular events by visualizing the opening and closure of aortic and mitral valves from the three-chamber apical view of LV and by placing a cursor corresponding to the mitral valve opening and closure and aortic valve opening and closure along the electrocardiogram trace.

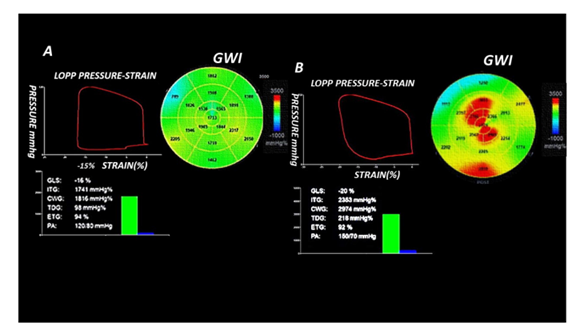

After the systolic blood pressure (measured at the brachial level by a sphygmomanometer at the time of acquisition) is incorporated into the software, a pressure-strain loop and an MW bull’s-eye plot are created (Figures 1A and 1B). Global values of MW are derived from the average of all 17 segments MW values (Figure 1B) [5].

Four values derived from the MW are generated according to the relationship of the segments with the different phases of the cardiac cycle. It is considered that a segment develops positive work when it is shortened and negative work when it is lengthened.

- Global working Index (GWI): It is the average MW and is represented by the area under the pressure-strain curve, the area is calculated from the closing of the mitral valve to the opening of it.

- Global construction work (GCW): Positive work performed by a segment in systole (segment shortening) and negative work (segment lengthening) during isovolumic relaxation.

- Global wasted work (GWW): negative work (segment lengthening) during systole and positive work (segment shortening) during isovolumic relaxation.

- Global work efficiency (GWE): GCW/(GCW+GWW).

The histogram represents global or segmental constructive and wasted work (Figure 1C).

The ranges in normal healthy controls from the EACVI NORRE study are shown in (Table 1) [6].

|

Name |

Female. Mean ± SD or median (IQR) |

Male. Mean ± SD or median (IQR) |

|

GWI (mmHg%) |

1924 ± 313 |

1849 ± 295 |

|

GCW (mmHg%) |

2234 ± 352 |

2228 ± 295 |

|

GWW (mmHg%) |

74 (49.5-111) |

94 (61.5-130.5) |

|

GWE (%) |

96 (94-97) |

95 (94-97) |

Figure 1. Measurement of myocardial work indices by 2D echocardiography in a normal case. A. Left ventricular pressure–strain loop (the red curve represents global myocardial work and the green to segment myocardial work). B. Bull’s eye of global work index (GWI). C. The green bars represent constructive work (GCW) and the blue bar for wasted work (GWW).

Figure 2. A. Young, obese, hypertensive grade 1, diabetic patient with preserved LVEF, GLS decreased for age, the area of the pressure-strain curve of the left ventricle, the GWI (bull's eye), the global constructive work (green bar) and the global wasted work (blue bar), all these parameters are preserved. B. It shows the data of a 70-year-old patient with grade 2 hypertension, normal GLS, the area of the pressure-strain curve, the bull’s-eye of the GWI (red and yellow segments correspond to high work, green segment to normal work), global construction work (green bar) and global wasted work (blue bar), all parameters are increased; the increase in GWW results in a decrease in GWE.

Figure 3. A middle-aged patient with delayed rescue coronary angioplasty in the anterior descending artery with LVFE (24%) and GLS (-8%) low, shows a narrow pressure-strain curve corresponding to a low myocardial work value, bull’s-eye of the GWI (segments with negative work are represented in blue and correspond to the extensive area of infarction), GCW and GWE all values are low. All MW components apart from GWE have the same units and are expressed in mmHg%, GWE is expressed in %.

Technical Limitations

The limitations on GLS acquisition also apply to MW. Several studies have tested the reproducibility of non-invasive MW indices, showing good results regarding both intra- and inter-observer variability [6].

GLS analysis depends on two-dimensional echocardiogram image quality, poor image quality, the presence of arrhythmias, and low frame rates, which may lead to incorrect segmental tracking for myocardial strain analysis.

Analysis of MW cannot be evaluated where LV systolic pressure is not equal to non-invasively estimated systolic blood pressure; as occurs in patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) or obstruction of the LV outflow tract, when the flow does not follow anterograde trajectory as significant mitral regurgitation, etc. Currently, patients with severe AS are evaluated with special consideration in the estimated LV pressure [12].

We should consider that MW may not be accurate in patients whose LV has undergone extensive remodeling, as it would not consider wall thickness or curvature important in determining parietal stress.

On the other hand, the pressure-volume loop is generated without considering changes in diastolic pressure, high diastolic blood pressure has been shown to affect MW, highlighting the need for future research in this regard [3].

Myocardial Work in Cardiac Disease

Hypertension

Increased afterload may result in a reduction in GLS, which gives the impression of reduced LV systolic function, however, the myocardium is not inefficient but performs greater force to maintain volume stroke. As in the analysis of MW, the afterload is considered which allows for distinguishing these two different situations. In patients with higher afterload, the GWI increases with increasing stages of hypertension (HTN), in uncontrolled hypertension the LV EF is usually seen within normal values, the GLS may be normal or decreased and the GWE is generally unchanged [7].

In young patients with well-controlled hypertension (HTN); LVEF, GLS, and MW are generally preserved; Figure 2A shows a young, obese patient, with grade 1 HTN well-controlled diabetes, highlights a low GLS value for ages but the rest of the MW parameters are preserved; however, Figure 2B shows the data corresponding to a 70-year-old patient with grade 2 HTN, LVFE, GLS preserved with MW increase consistent with the degree of HTN but the increase in GWW with the consequent decrease in GWE, in patients with controlled HTN there is generally no increase in GWW or decrease in GWE.

Studies evaluating MW parameters over time are needed to provide information on the clinical role in the follow-up of this pathology.

Athlete’s heart

Long-term intense physical training induces adaptive changes in cardiac structure and functions to maintain high cardiac output during exertion, this physiological remodeling leads to increased myocardial contractility.

Athletes often exhibit systolic function parameters (LVEF, GLS) in the low-normal range at rest despite increased contractile reserve. This can lead to an ambiguous interpretation of resting echocardiograms, making it difficult to differentiate between physiological remodeling or pathological processes of LV.

Tokodi et al. found decreased GLS values in elite swimmers but with an increase in GWI at rest, and GWI was positively correlated with peak oxygen consumption during exercise. This study suggests that GWI at rest may more accurately predict athlete heart performance than other markers of LV systolic function.

MW is a novel, non-invasive technique promising in evaluating the athlete's heart, as it is less dependent on load and sex-related conditions [8].

On the other hand, studies of the pattern of MW in the different sports disciplines are necessary since they could help to differentiate adaptive hypertrophy and cardiomyopathy in athletes.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

In patients with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM), myocardial fiber disarray and interstitial fibrosis are responsible for the progressive alteration of LV deformation parameters, which precedes overt LV dysfunction.

Galli et al. demonstrated a significant reduction in GCW assessed with an echocardiogram in patients with non-obstructive HCM compared to healthy controls, also showing that low GCW is associated with fibrosis on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging [9]. This finding was also noted by Goncalves et al., who found that a GCW value of ≤1550 mmHg% was associated with a significant increase in late gadolinium enhancement ≥ 15% on cardiac MRI with a sensitivity of 91% and a specificity of 84%, suggesting that it could be useful in patients who cannot undergo a cardiac MRI study [10].

A study by Hiemstra et al. demonstrated that patients with a GCW >1730 mmHg% had better event-free survival (P<0.001) [11]. This correlation between GCW and fibrosis marker on MRI is important since it would be a finding in the sub-clinical stage that could be detected in a routine resting echocardiogram with prognostic significance.

Aortic stenosis

Patients with severe AS were excluded from the initial validation studies of the MW analysis, as systolic blood pressure cannot be used as a substitute for LV systolic pressure in the setting of fixed obstruction. Fortuni et al. found that in severe AS the sum of non-invasive systolic blood pressure and mean aortic gradient measured by Doppler correlates closely with invasively measured LV systolic pressure [12].The use of myocardial work can also clarify two serious phenotypes of AS: patients with abnormal GLS and high MW and those with abnormal GLS and reduced MW; the latter group probably represents a phase in which LV compensatory mechanisms have already failed with more permanent LV dysfunction post percutaneous valve replacement (TAVR) [13]. A recent study showed an increase in GWI, GCW, and GWW in patients with asymptomatic moderate-to-severe AS with preserved LVEF compared to controls and that a GWI ≤ 1951 mmHg% and a GCW ≤ 2475 mmHg% accurately predicted all-cause and cardiovascular death at 4-year follow-up [14].

According to our experience, we consider that each case should be individualized. We recently published the case of an octogenarian patient with severe AS, GLS, GWI, GCW, GWE decreased and mild decrease LVEF pre-TAVR, unlike patients with severe AS that compensate with increased GWI, GCW without a decrease in GWE, the work pattern in our patient was interpreted secondary to extensive myocardial ischemia since the parameters of MW reversed after coronary revascularization and post-TAVR [15]. Not all patients with low pre-TAVR MW will have a poor prognosis post-TAVR, especially if it is associated with treatable coronary heart disease. In the future, we will need studies that evaluate the usefulness of the MW in patients with pure severe AS and separately patients with associated pathologies.

Cardiac dyssynchrony

A great advance in the evaluation of LV performance through myocardial working curves was the analysis of negative or non-contributory work to LV ejection. Normally, all segments contract synchronously, and myocardial energy is effectively used to expel blood from the LV. In ventricles with regional differences in contractility, some segments are normally shortened, while others are abnormally stretched in systole, resulting in a dyssynchronous contraction pattern, so an amount of myocardial work is "wasted" on segment stretching and therefore does not contribute effectively to LV ejection [4].

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) is an effective therapy that aims to restore mechanical efficiency to the failing LV by resynchronizing the contraction of the left and right ventricles, resulting in a reduction of both morbidity and mortality. However, the number of patients who do not respond to CRT remains high. Galli et al. were able to show that at baseline echocardiogram, septal GWW and global GCW were higher in CRT responders than in non-responders. After 6 months of follow-up, CRT responders presented an increase in GCW and a reduction in GWW associated with LV reverse remodeling, the combination of GCW>1057 mm Hg% and septal wasted work >364 mm Hg% showed very good specificity with high positive predictive value but low sensitivity and low negative predictive value with which accuracy for the prediction of CRT responders remains low [16]. In a recently published study that evaluated patients with unfavorable electrical characteristics, among the echocardiographic parameters of electromechanical dyssynchrony evaluated before CRT (septal flash, apical balancing, septal deformation patterns, and septal wasted work (SWW) determined with the use of STE) in multivariate analysis an SWW ≥ 200 mm Hg% and GLS septal patterns 1 and 2 (segment stretching in systole and post-systolic shortened respectively) were associated with CRT response. During a 46-month follow-up, survival free from death or heart failure hospitalization increased with the number of positive criteria (87% for 2, 59% for 1, and 27% for 0 criteria) [17]. Given the existence of numerous independent mechanisms influencing CRT response, it is suggested that the combination of clinical, electrocardiographic, and echocardiographic data could be more useful in detecting CRT responders.

Coronary artery disease

Non-invasive detection of functionally significant coronary artery disease (CAD) by rest echocardiography remains a challenge. In a study evaluating MW in patients without segmental motility abnormalities with preserved LVEF, a low GWI value in rest was the most powerful predictor of significant CAD even higher than GLS. The optimal cut-off GWI value to predict significant CAD was 1,810 mm Hg% (sensitivity, 92%; specificity, 51%) [18].

Future studies are needed to evaluate this potentially valuable clinical tool to aid in the early diagnosis of CAD.

On the other hand, Coisine et al. investigated the additional prognostic value of MW parameters after acute myocardial infarction (AMI) by finding that GWE <91% at 1 month after AMI is independently associated with increased risk of major events [19]. In patients with evolved myocardial infarctions or with delayed rescue angioplasty, the parameters of myocardial work can add prognostic information (Figure 3).

Dilated cardiomyopathy

It is known that in heart failure (HF) patients with decreased LVEF the GLS is more accurate in predicting the prognosis than LVEF, but both parameters depend on the load, so the MW is interesting in this aspect. In a recently published study that included patients with EF <40%, GWI <750 mmHg% was associated with an increased risk of death from all causes and hospitalization for HF than patients with GWI >750 mmHg%. These results extend the use of MW in patients with EF <40% to estimate survival and future hospitalization rates in this group [20].

Future studies with HF patients with preserved or decreased LVEF are needed to assess the usefulness of MW in treatment adjustment, event prediction, etc.

Conclusions

Myocardial work analysis is a new technique with which LV performance can be evaluated with the advantage of being less load-dependent on LVEF and GLS.

Some studies have shown the superiority of MW as a prognostic marker concerning GLS, although large-scale studies for pathologies are still needed.

In daily practice, we need to individualize the cases well considering the associated pathologies, and complement the MW with other techniques.

References

2. Chan J, Edwards NF, Scalia GM, Khandheria BK. Myocardial work: a new type of strain imaging?. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2020 Oct 1;33(10):1209-11.

3. Jaglan A, Roemer S, Khandheria B. Myocardial work index: it works. European Heart Journal-Cardiovascular Imaging. 2020 Sep 1;21(9):1049.

4. Russell K, Eriksen M, Aaberge L, Wilhelmsen N, Skulstad H, Gjesdal O, et al. Assessment of wasted myocardial work: a novel method to quantify energy loss due to uncoordinated left ventricular contractions. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2013 Oct 1;305(7):H996-1003.

5. Papadopoulos K, Özden Tok Ö, Mitrousi K, Ikonomidis I. Myocardial work: methodology and clinical applications. Diagnostics. 2021 Mar 22;11(3):573.

6. Manganaro R, Marchetta S, Dulgheru R, Ilardi F, Sugimoto T, Robinet S, et al. Echocardiographic reference ranges for normal non-invasive myocardial work indices: results from the EACVI NORRE study. European Heart Journal-Cardiovascular Imaging. 2019 May 1;20(5):582-90.

7. Chan J, Edwards NF, Khandheria BK, Shiino K, Sabapathy S, Anderson B, et al. A new approach to assess myocardial work by non-invasive left ventricular pressure–strain relations in hypertension and dilated cardiomyopathy. European Heart Journal-Cardiovascular Imaging. 2019 Jan 1;20(1):31-9.

8. Tokodi M, Oláh A, Fábián A, Lakatos BK, Hizoh I, Ruppert M, et al. Novel insights into the athlete’s heart: is myocardial work the new champion of systolic function?. European Heart Journal-Cardiovascular Imaging. 2022 Feb 1;23(2):188-97.

9. Galli E, Vitel E, Schnell F, Le Rolle V, Hubert A, Lederlin M, et al. Myocardial constructive work is impaired in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and predicts left ventricular fibrosis. Echocardiography. 2019 Jan;36(1):74-82.

10. Gonçalves AV, Rosa SA, Branco L, Galrinho A, Fiarresga A, Lopes LR, et al. Myocardial work is associated with significant left ventricular myocardial fibrosis in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The International Journal of Cardiovascular Imaging. 2021 Jul;37:2237-44.

11. Hiemstra YL, van der Bijl P, El Mahdiui M, Bax JJ, Delgado V, Marsan NA. Myocardial work in nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: implications for outcome. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2020 Oct 1;33(10):1201-8.

12. Fortuni F, Butcher SC, van der Kley F, Lustosa RP, Karalis I, de Weger A, et al. Left ventricular myocardial work in patients with severe aortic stenosis. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2021 Mar 1;34(3):257-66.

13. Jain R, Khandheria BK, Tajik AJ. Myocardial work in aortic stenosis: it does work!. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2021 Mar 1;34(3):267-9.

14. Ilardi F, Postolache A, Dulgheru R, Trung ML, de Marneffe N, Sugimoto T, et al. Prognostic value of non-invasive global myocardial work in asymptomatic aortic stenosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022 Mar 11;11(6):1555.

15. Sanchez ME, Panno MA, Epelbaum JE. Trabajo mioca rdico antes y despue s del TAVI en paciente crıtico.

16. Galli E, Leclercq C, Hubert A, Bernard A, Smiseth OA, Mabo P, et al. Role of myocardial constructive work in the identification of responders to CRT. European Heart Journal-Cardiovascular Imaging. 2018 Sep 1;19(9):1010-8.

17. Layec J, Decroocq M, Delelis F, Appert L, Guyomar Y, Riolet C, et al. Dyssynchrony and response to cardiac resynchronization therapy in heart failure patients with unfavorable electrical characteristics. Cardiovascular Imaging. 2023 Jul 1;16(7):873-84.

18. Edwards NFA, Scalia GM, Shiino K, Sabapathy S, Anderson B, Chamberlain R, et al. Superior to Global Longitudinal Strain to Predict Significant Coronary Artery Disease in Patients with Normal Left Ventricular Function and Wall Motion. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2019 Aug;32(8):947-57.

19. Coisne A, Fourdinier V, Lemesle G, Delsart P, Aghezzaf S, Lamblin N, et al. Clinical significance of myocardial work parameters after acute myocardial infarction. European Heart Journal Open. 2022 May 1;2(3):oeac037.

20. Wang CL, Chan YH, Wu VC, Lee HF, Hsiao FC, Chu PH. Incremental prognostic value of global myocardial work over ejection fraction and global longitudinal strain in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. European Heart Journal-Cardiovascular Imaging. 2021 Mar 1;22(3):348-56.