Abstract

The interplay between neural cells and immune cells is a determinant factor for microenvironment restoration following nerve injury. Nerve-resident immune cells respond microenvironment signals and switch to pro-inflammatory or pro-regenerative phenotype. These phenotypes have different effects on axon regeneration. Early-phase neuroinflammation clears debris and remodels a permissive microenvironment for nerve repair. However, persistent and overactive inflammation is destructive and detrimental to regeneration. Despite all this information, our understanding of neuroimmune interplay in traumatic and diabetic neuropathies remains poor. Early studies on neuroimmune interplay focused on tissue defenses, in which nerve ending modulates the immune function in peripheral tissues, maximizing the sensing and defensing abilities to environmental aggressions. With the identification of cellular and molecular profile of injured nerves, the interaction between immune cells and other nerve-resident cells, e.g., Schwann cells and vessel cells, becomes clearer. In our recently published studies, we identified key proteins that impacts the regeneration of injured nerves by proteomic sequencing. We also identified that mast cells play key roles in DPN progression by single-cell RNA sequencing. These discoveries were further verified in transgenic mice. This commentary summarizes the neuroimmune interplay in diabetic peripheral neuropathy and traumatic peripheral nerve injury, and the potential treatment via blockade of neuroimmune axis.

Keywords

Neuroimmune interplay, Diabetes, Trauma, Neuropathy, Neuroinflammation

Commentary

Dysregulation of neuroimmune interplay is a common feature of many neurodegenerative diseases [1,2]. Upon injury, glial cells respond to insults with excessive activation and produce both beneficial and detrimental factors [3,4]. Immune cells in nerve tissue detect pathological signals and adapt their inflammatory phenotype accordingly [5,6]. Dysregulated neuroimmune interplay maintains nerve-resident macrophages in a constantly reactive state and thus induces sustained neuroinflammation, which enhances neuronal damage [7]. Nonetheless, the molecular regulators of neuroimmune crosstalk in peripheral nerve tissue are less explored.

Building on our recent work [8], this commentary presents new findings and insights on the molecular components that mediate the dysregulated neuroimmune crosstalk in the context of traumatic nerve injury (TPNI) and diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN). Identifying key molecular components of neuroimmune interplay is critical for developing targeted therapeutic strategies for both acute and chronic neuropathies. For example, nerve scaffolds or nerve-wrapping membrane loaded with specific neutralizing antibodies and immune modulating agents can be a promising treatment for TPNI and DPN.

Schwann Cell-Macrophage Crosstalk Driving Sustained Neuroinflammation Following TPNI

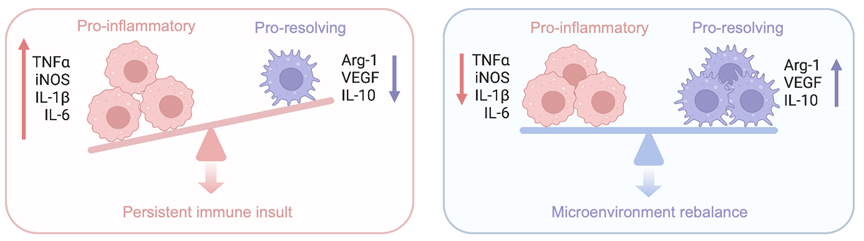

Following neurotrauma, peripheral nerves initiate a self-destruction program called Wallerian degeneration. During Wallerian degeneration, Schwann cells and axotomized neurons produce chemokine C-C motif ligand 2 (CCL2) which drives the accumulation of circulating macrophages to the injury site and distal nerves [9]. Schwann cells shift their phenotype to a dedifferentiated stage to initiate regeneration program. Dedifferentiated Schwann cells produce pro-regenerative signals and growth suppressors to reshape the nerve microenvironment. The early immune response is dominated by pro-inflammatory macrophages, characterized by the expression of tumor necrotic factor-α (TNF-α) and iNOS, phenotypically programmed for myelin debris clearance [10]. However, during regeneration stage proinflammatory macrophages are replaced by pro-regenerative macrophages, characterized by the expression of CD206, Arginase-1 (Arg-1) and Ym1 (classic markers for M2-like macrophages) [11]. Delayed phenotypic transition of macrophages can cause retardation of axon regrowth [17], as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Macrophage-mediated microenvironment immune rebalance and imbalance in peripheral nerve regeneration.

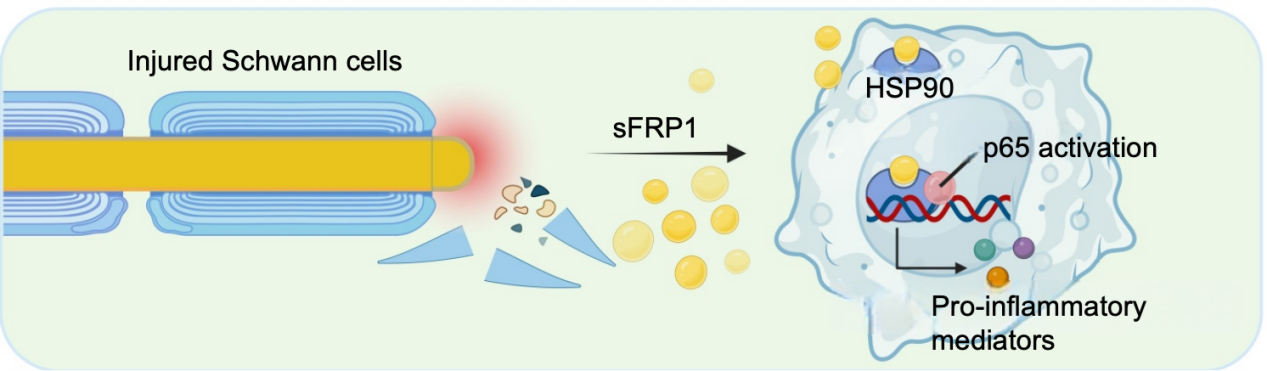

In our research, we performed a proteomic sequencing analysis of murine sciatic nerves, identifying Schwann cell secreted frizzled-related protein 1 (sFRP1) as the most upregulated protein following TPNI identified via proteomic sequencing [8]. Genetic deletion of sFRP1 robustly alleviated posttraumatic neuroinflammation and accelerated axon regeneration. We then focused on the crosstalk of macrophage and Schwann cells due to their strong association with neuroinflammation. To identify the binding protein of sFRP1, we incubated macrophage-derived total proteins with His-labeled sFRP1 and performed immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry (IP-MS) analysis. As revealed by IP-MS results, heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) was listed as the potential interaction partner of sFRP1. Thereafter, we performed IP experiment to assess the direct binding of sFRP1 to HSP90 using an HSP90 IP antibody, followed by immunoblotting validation of sFRP1 in macrophage lysates. HSP90 has been reported to bind to inflammasomes as a cofactor, causing the abnormal activation of these inflammasomes in macrophages [12,13]. Further analysis proved that HSP90 knockdown significantly reversed the proinflammatory phenotype of macrophages caused by sFRP1 treatment and induced a pro-resolving phenotype. These findings suggest that the sFRP1-HSP90 axis plays a critical role in Schwann cell-macrophage crosstalk, potentially exacerbating neuroinflammation and axon degeneration in regenerated nerves (Figure 2). Consistent with our study, sFRP1 fosters dysfunctional astrocyte-microglia crosstalk in the brain and thus exacerbates the progression of neurodegenerative diseases [1]. Further research is needed to explore distinct proteins modulating neuroimmune interplay at different time points following neurotrauma.

Figure 2. Schwann cell-secreted sFRP1 dictates macrophage proinflammatory phenotype by binding with HSP90.

Mast Cell-Neuron Crosstalk Underlying DPN Progression

The pathogenic mechanism of DPN remains poorly understood, for which few therapeutic strategies have been developed. Increasing evidence supports a role of neuroinflammation in the pathogenesis of DPN. Diabetes-associated immune imbalance causes successive damage in neural structure and function [14]. Low-grade inflammation maintained by aberrant immune cell infiltration characterizes a pivotal aspect of DPN pathology [15]. Therefore, in search of more effective therapeutics for DPN, it becomes paramount to understand the neuroimmune interplay underlying DPN pathogenesis.

Current research on neuroimmune crosstalk in peripheral nerve system mainly focuses on macrophages [16,17]. One research reported the pathogenesis of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy induced by neutrophil extracellular traps (NET) [18]. Indeed, NET plays an important role in causing the inflammation and injury [19,20]. The reversible CD8+ T cell-neuron crosstalk was also reported to be critical driver for aging-dependent regenerative decline following TPNI [21]. Relatively few studies have reported how other immune cells affect the homeostasis of nerve microenvironment.

Mast cells are innate immune cells, and their state is largely controlled by local microenvironment [22]. Once activated, mast cells rapidly degranulate, releasing large amounts of preformed mediators into local microenvironment, including proteases, inflammatory cytokines, and chemokines [23]. However, it remains unclear whether mast cells act as active participants or just dispensable bystanders in PNS diseases. In our recent research, we proposed that dysregulated mast cell-neuron crosstalk causes successive and irreversible damage to axons during DPN progression [24]. We recruited DPN patients undergoing amputation surgeries for diabetic foot ulcer. Diabetic foot ulcer is the commonest major end-point of diabetic complications and most frequent precursor to amputation [25,26]. Neuropathy in lower limbs is one of the main etiological factors in foot ulceration [27]. Therefore, neural pathological changes are most pronounced and typical in tibial and sural nerves. To delineate the cellular identities of neuroimmune interaction during DPN progression, we performed single cell-sequencing analysis on tibial nerves isolated from DPN and TPNI patients. We found robustly increased mast cell population, marked by TPSAB1, CMA1 and KIT expression, in DPN nerves, compared with the TPNI counterparts. In comparison, only few of mast cells were observed in TPNI nerves. To further understand mast cell heterogeneity at the transcriptional level, we reanalyzed mast cell sequencing data and noted that mast cells were categorized into 7 heterogenous subclusters. Based on the subclustering outcome, we identified 2 distinct clusters with a unique transcriptional profile that emerged only in DPN nerves. One cluster was marked by HMGB1 and HMGB2, and the other cluster was marked by CCL5 and IL32. GO enrichment analysis indicated that leukocyte activities, mast cell degranulation, prostaglandin metabolism and oxidative stress were significantly enriched in mast cells during DPN progression. KEGG enrichment analysis further revealed that DPN mast cells were significantly enriched in TNF-? signaling, MAPK1 signaling, and NF-κB signaling.

Mast cells are classically related to allergic responses but also contribute to several inflammatory diseases such as conjunctivitis, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and aortic aneurysm [28–32]. In irritant dermatitis responses, cutaneous mast cells amplify skin inflammation through the release of granules containing multiple inflammatory meditators [33]. A few studies also reported mast cells as the pathological factor in the onset and progression of diabetes and related complications [34–37]. A previous study reported that increase in mast cell numbers and degranulation level correlated significantly with tubular interstitial injury [35]. Topical application of mast cell stabilizers alleviated the local inflammation in diabetic wound and improved wound healing [36]. Another research reported that infiltrated mast cells are the trigger of small vessel disease and diastolic dysfunction in diabetic mice [37]. High numbers of mast cells infiltrate in the white adipose tissue of type 2 diabetes and produce inflammatory factors which exacerbate glucose intolerance [34]. These findings demonstrate that tissue-resident mast cells could be key components of chronic inflammation in the local tissue of diabetic individuals. Consistent with these studies, our research observed increased mast cells infiltration and degranulation, accompanied by neuroinflammation and axon damage, in peripheral nerves of diabetic patients [24]. Dysregulated mast cells damage the mitochondrial respiration of neurons and suppress axon regrowth via paracrine signaling mechanisms [24]. Genetic clearance of mast cells in murine DPN model effectively halted the progression of neuropathy and neuroinflammation [24]. These findings broaden the understanding of neuroimmune interplay underlying chronic peripheral neuropathy.

Susceptibility of Peripheral Nerves to Immune Insults

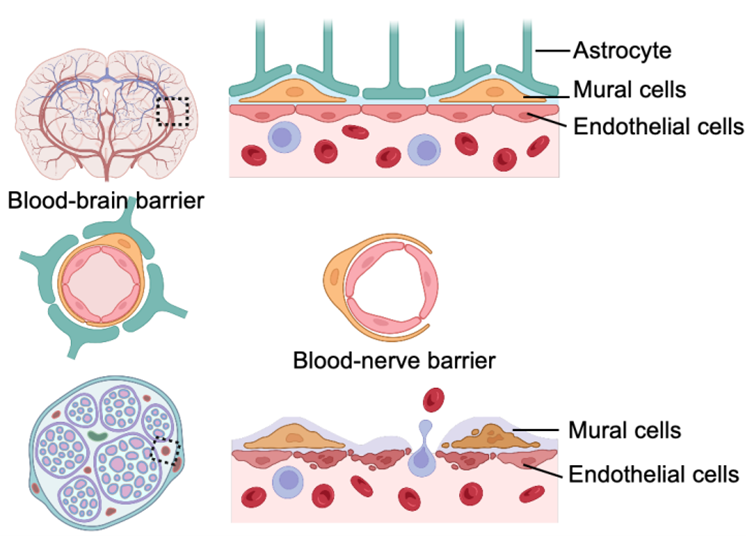

As described above, peripheral nervous system is susceptible to immune insults which cause acute and chronic neuroinflammation. A peripheral nerve consists of 3 compartments, endoneurium, perineurium and epineurium. Like the blood-brain barrier in central nervous system, peripheral nerves contain a blood-nerve barrier composed of endothelial cells, pericytes, and basal laminae [38]. As depicted in Figure 3, blood-nerve barrier in peripheral nerves is leakier and more permeable compared to the blood-brain barrier, due to the lack of astrocytes [39]. Determined by such anatomy, peripheral nerves are susceptible to the extravasation of circulating immune cells upon nerve injury [40]. The increased endoneurial microvascular permeability reflects an adaptive reorganization of capillary structure and function in response to altered conditions of nerve microenvironment [41]. This permeability increase is induced by breakdown of endothelial cells or damage of mural cels enveloping the blood endothelium [42]. Multipotent stem cell transplantation, exosomes, and proangiogenic cytokines can effectively promote angiogenesis and enhance the formation of tight junctions in endothelial cells and mural cells [43–45]. Therefore, reconstruction of blood-nerve barrier stabilizes the neuroimmune interplay which maintains the internal homeostasis of peripheral nerves.

Figure 3. Components of blood-brain barrier and blood-nerve barrier.

Despite multiple studies revealing the importance of immune homeostasis, there are still questions to be addressed: (1) Due to the significant variation in immune cell types resided in nerves among different neuropathies, researchers need to investigate the optimal immune-modulating targets for clinical translation. Inhibition of these targets can yield the greatest nerve-protective results and better safety profiles. (2) Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved immunotherapies for central nervous system diseases have expanded over the past few decades [46]. However, the mechanism of action may vary when shifting from central nervous system diseases to peripheral neuropathies. For example, sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor (S1PR) modulators were proved to be effective in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis [46], and have superior effects in murine axonal and Schwann cell regeneration [47]. However, the pro-regenerative effect of pharmacological S1PR stimulation is compromised in human nerves [48]. In the future, it will be crucial to balance risks with the anticipated efficacy of immune-modulating therapies when selecting treatments. (3) It remains to be verified whether the key proteins regulating neuroimmune interplay vary at various stages during the progression of neuropathy. Strategies such as longitudinal proteomics or time-resolved single-cell analysis will facilitate the development of period-based therapeutics.

Conclusions

In summary, our findings highlight the importance of understanding neuroimmune crosstalk within peripheral nerves and identifying dysregulated cytokines that exacerbate neuroinflammation. Neuroinflammation, the inflammatory response in the peripheral nervous system following injury, is often described as a “double-edged sword”, as it can produce both beneficial and detrimental effects. This understanding sheds light on cell-specific mechanisms underlying traumatic and diabetic peripheral neuropathies and offer potential targets for therapy.

Compared with systemic administration of drugs, local administration can directly deliver high concentration of therapeutic agents to the nerve tissue, improving drug delivery efficiency and avoiding systemic complications. In recent years, with the increasing knowledge in tissue engineering, a number of neural-supporting scaffolds are applied in enhancing nerve repair. In this context, nerve scaffold represents an effective strategy for targeted delivery of therapeutic agents to nerve injury site. For TPNI, nerve conduits loaded with sFRP1 antibody can be a potential strategy to block sFRP1-HSP90 axis, thereby relieving persistent and overactive neuroinflammation. For DPN, nerve-wrapping membrane loaded with mast cell-stabilizing agents, such as disodium cromoglycate (DSCG), can be an effective strategy to rebalance immune homeostasis in DPN nerves. However, current challenges for the clinical translation are complicated nerve physiological environment and uncontrollable drug releasing processes. These challenges necessitate more precise definition of nerve pathophysiological and recovery process.

References

2. Cai W, Wang J, Hu M, Chen X, Lu Z, Bellanti JA, et al. All trans-retinoic acid protects against acute ischemic stroke by modulating neutrophil functions through STAT1 signaling. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2019 Aug 31;16(1):175.

3. Hu Z, Deng N, Liu K, Zhou N, Sun Y, Zeng W. CNTF-STAT3-IL-6 axis mediates neuroinflammatory cascade across Schwann cell-neuron-microglia. Cell reports. 2020 May 19;31(7):107657.

4. Jessen KR, Arthur‐Farraj P. Repair Schwann cell update: Adaptive reprogramming, EMT, and stemness in regenerating nerves. Glia. 2019 Mar;67(3):421–37.

5. Kierdorf K, Prinz M. Factors regulating microglia activation. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience. 2013 Apr 23;7:44.

6. Cai W, Liu S, Hu M, Huang F, Zhu Q, Qiu W, et al. Functional dynamics of neutrophils after ischemic stroke. Translational stroke research. 2020 Feb;11(1):108–21.

7. Zhao XF, Huffman LD, Hafner H, Athaiya M, Finneran MC, Kalinski AL, et al. The injured sciatic nerve atlas (iSNAT), insights into the cellular and molecular basis of neural tissue degeneration and regeneration. Elife. 2022 Dec 14;11:e80881.

8. Yao X, Kong L, Qiao Y, Brand D, Li J, Yan Z, et al. Schwann cell-secreted frizzled-related protein 1 dictates neuroinflammation and peripheral nerve degeneration after neurotrauma. Cell Reports Medicine. 2024 Nov 19;5(11):101791.

9. Kwon MJ, Shin HY, Cui Y, Kim H, Le Thi AH, Choi JY, et al. CCL2 mediates neuron–macrophage interactions to drive proregenerative macrophage activation following preconditioning injury. Journal of Neuroscience. 2015 Dec 2;35(48):15934–47.

10. Brosius Lutz A, Chung WS, Sloan SA, Carson GA, Zhou L, Lovelett E, et al. Schwann cells use TAM receptor-mediated phagocytosis in addition to autophagy to clear myelin in a mouse model of nerve injury. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2017 Sep 19;114(38):E8072–80.

11. Nadeau S, Filali M, Zhang J, Kerr BJ, Rivest S, Soulet D, et al. Functional recovery after peripheral nerve injury is dependent on the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF: implications for neuropathic pain. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011 Aug 31;31(35):12533–42.

12. Xu G, Fu S, Zhan X, Wang Z, Zhang P, Shi W, et al. Echinatin effectively protects against NLRP3 inflammasome–driven diseases by targeting HSP90. JCI insight. 2021 Jan 25;6(2):e134601.

13. Mayor A, Martinon F, De Smedt T, Pétrilli V, Tschopp J. A crucial function of SGT1 and HSP90 in inflammasome activity links mammalian and plant innate immune responses. Nature immunology. 2007 May;8(5):497–503.

14. Eid SA, Rumora AE, Beirowski B, Bennett DL, Hur J, Savelieff MG, et al. New perspectives in diabetic neuropathy. Neuron. 2023 Sep 6;111(17):2623–41.

15. Osonoi S, Mizukami H, Takeuchi Y, Sugawa H, Ogasawara S, Takaku S, et al. RAGE activation in macrophages and development of experimental diabetic polyneuropathy. JCI insight. 2022 Dec 8;7(23):e160555.

16. Cattin AL, Burden JJ, Van Emmenis L, Mackenzie FE, Hoving JJ, Calavia NG, et al. Macrophage-induced blood vessels guide Schwann cell-mediated regeneration of peripheral nerves. Cell. 2015 Aug 27;162(5):1127–39.

17. Zigmond RE, Echevarria FD. Macrophage biology in the peripheral nervous system after injury. Progress in neurobiology. 2019 Feb 1;173:102–21.

18. Wang CY, Lin TT, Hu L, Xu CJ, Hu F, Wan L, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps as a unique target in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. EBioMedicine. 2023 Apr 1;90:104499.

19. Zhao J, Liu Y, Shi X, Dang J, Liu Y, Li S, et al. Infusion of GMSCs relieves autoimmune arthritis by suppressing the externalization of neutrophil extracellular traps via PGE2-PKA-ERK axis. Journal of Advanced Research. 2024 Apr 1;58:79–91.

20. Tan Z, Jiang R, Wang X, Wang Y, Lu L, Liu Q, et al. RORγt+ IL-17+ neutrophils play a critical role in hepatic ischemia–reperfusion injury. Journal of molecular cell biology. 2013 Apr 1;5(2):143–6.

21. Zhou L, Kong G, Palmisano I, Cencioni MT, Danzi M, De Virgiliis F, et al. Reversible CD8 T cell–neuron cross-talk causes aging-dependent neuronal regenerative decline. Science. 2022 May 13;376(6594):eabd5926.

22. Elieh Ali Komi D, Wöhrl S, Bielory L. Mast cell biology at molecular level: a comprehensive review. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology. 2020 Jun;58(3):342–65.

23. Bulfone-Paus S, Nilsson G, Draber P, Blank U, Levi-Schaffer F. Positive and negative signals in mast cell activation. Trends in immunology. 2017 Sep 1;38(9):657–67.

24. Yao X, Wang X, Zhang R, Kong L, Fan C, Qian Y. Dysregulated mast cell activation induced by diabetic milieu exacerbates the progression of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in mice. Nature Communications. 2025 May 5;16(1):4170.

25. Theocharidis G, Thomas BE, Sarkar D, Mumme HL, Pilcher WJ, Dwivedi B, et al. Single cell transcriptomic landscape of diabetic foot ulcers. Nature communications. 2022 Jan 10;13(1):181.

26. Sinwar PD. The diabetic foot management–Recent advance. International Journal of Surgery. 2015 Mar 1;15:27–30.

27. McDermott K, Fang M, Boulton AJ, Selvin E, Hicks CW. Etiology, epidemiology, and disparities in the burden of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes care. 2023 Jan 2;46(1):209–21.

28. Galli SJ, Nakae S, Tsai M. Mast cells in the development of adaptive immune responses. Nature immunology. 2005 Feb 1;6(2):135–42.

29. Lee DM, Friend DS, Gurish MF, Benoist C, Mathis D, Brenner MB. Mast cells: a cellular link between autoantibodies and inflammatory arthritis. Science. 2002 Sep 6;297(5587):1689–92.

30. Sun J, Sukhova GK, Yang M, Wolters PJ, MacFarlane LA, Libby P, Sun C, Zhang Y, Liu J, Ennis TL, Knispel R. Mast cells modulate the pathogenesis of elastase-induced abdominal aortic aneurysms in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007 Nov 1;117(11):3359–68.

31. Su W, Wan Q, Huang J, Han L, Chen X, Chen G, Olsen N, Zheng SG, Liang D. Culture medium from TNF-α–stimulated mesenchymal stem cells attenuates allergic conjunctivitis through multiple antiallergic mechanisms. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2015 Aug 1;136(2):423–32.

32. Su W, Fan H, Chen M, Wang J, Brand D, He X, et al. Induced CD4+ forkhead box protein–positive T cells inhibit mast cell function and established contact hypersensitivity through TGF-β1. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2012 Aug 1;130(2):444–52.

33. Zhang S, Edwards TN, Chaudhri VK, Wu J, Cohen JA, Hirai T, et al. Nonpeptidergic neurons suppress mast cells via glutamate to maintain skin homeostasis. Cell. 2021 Apr 15;184(8):2151–66.

34. Liu J, Divoux A, Sun J, Zhang J, Clément K, Glickman JN, et al. Genetic deficiency and pharmacological stabilization of mast cells reduce diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Nature medicine. 2009 Aug;15(8):940–5.

35. Zheng JM, Yao GH, Cheng Z, Wang R, Liu ZH. Pathogenic role of mast cells in the development of diabetic nephropathy: a study of patients at different stages of the disease. Diabetologia. 2012 Mar;55(3):801–11.

36. Tellechea A, Bai S, Dangwal S, Theocharidis G, Nagai M, Koerner S, et al. Topical application of a mast cell stabilizer improves impaired diabetic wound healing. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2020 Apr 1;140(4):901–11.

37. Guimbal S, Cornuault L, Rouault P, Hollier PL, Chapouly C, Bats ML, et al. Mast cells are the trigger of small vessel disease and diastolic dysfunction in diabetic obese mice. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2021 Apr;41(4):e193–207.

38. Takeshita Y, Sato R, Kanda T. Blood–nerve barrier (BNB) pathology in diabetic peripheral neuropathy and in vitro human BNB model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020 Dec 23;22(1):62.

39. Poduslo JF, Curran GL, Berg CT. Macromolecular permeability across the blood-nerve and blood-brain barriers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1994 Jun 7;91(12):5705–9.

40. Rechthand E, Smith QR, Latker CH, Kapoport SI. Altered blood-nerve barrier permeability to small molecules in experimental diabetes mellitus. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology. 1987 May 1;46(3):302–14.

41. Lefrandt JD, Bosma E, Oomen PH, Van Der Hoeven JH, Van Roon AM, Smit AJ, et al. Sympathetic mediated vasomotion and skin capillary permeability in diabetic patients with peripheral neuropathy. Diabetologia. 2003 Jan;46(1):40–7.

42. Dudeck J, Kotrba J, Immler R, Hoffmann A, Voss M, Alexaki VI, et al. Directional mast cell degranulation of tumor necrosis factor into blood vessels primes neutrophil extravasation. Immunity. 2021 Mar 9;54(3):468–83.

43. Huang CW, Hsueh YY, Huang WC, Patel S, Li S. Multipotent vascular stem cells contribute to neurovascular regeneration of peripheral nerve. Stem cell research & therapy. 2019 Aug 3;10(1):234.

44. Dong T, Li M, Gao F, Wei P, Wang J. Construction and imaging of a neurovascular unit model. Neural Regeneration Research. 2022 Aug 1;17(8):1685–94.

45. Huang J, Li J, Li S, Yang X, Huo N, Chen Q, et al. Netrin-1–engineered endothelial cell exosomes induce the formation of pre-regenerative niche to accelerate peripheral nerve repair. Science Advances. 2024 Jun 28;10(26):eadm8454.

46. Derfuss T, Mehling M, Papadopoulou A, Bar-Or A, Cohen JA, Kappos L. Advances in oral immunomodulating therapies in relapsing multiple sclerosis. The Lancet Neurology. 2020 Apr 1;19(4):336–47.

47. Li C, Yamamoto T, Kanemaru H, Kishimoto N, Seo K. Effects of sphingosine-1-phosphate on the facilitation of peripheral nerve regeneration. Cureus. 2024 Nov 15;16(11):84.

48. Meyer zu Reckendorf S, Brand C, Pedro MT, Hegler J, Schilling CS, Lerner R, et al. Lipid metabolism adaptations are reduced in human compared to murine Schwann cells following injury. Nature Communications. 2020 May 1;11(1):2123.