Abstract

Self-injurious behavior or Non-Suicidal Self Injury (NSSI) is rapidly increasing in prevalence in the adolescent populations of the western world. Nevertheless, the training and education for physicians concerning this topic remains limited. Combined with NSSI’s tendency to become addictive in nature and continue well past adolescence, this particular issue is important for the physician to understand to provide adequate long-term treatment. Due to the overwhelming responsibility for the physician to understand and treat the entire patient, this particular article looks to clear the muddy waters surrounding NSSI, discuss how it can become an addiction, review the literature, discuss treatments and therapies, and provide key clinical pearls on building and maintaining relationships with patients afflicted by this disorder.

Keywords

Self-harm addiction, Non-suicidal self injury addiction, Physician guide, Literature review, Treatments and therapies, Patient rapport, NSSI, Non-suicidal self injury, Self injury, Perfectionism

NSSI Addiction and The Physician: A Narrative Literature Review and Best Practices Guide

Patients can often struggle from a multitude of disorders including, but not limited to, those which affect their physical, emotional, and psychological well-being. Due to the difficulty in the evaluation and treatment of these psychological disorders, they are often brushed over or ignored during lesson presented in medical school and later medical training such as residency or fellowship. Regardless of the excellence of the medical center, these disorders and their treatment can and should be improved upon for the betterment of our deserving patients. On top of the struggles with the disorders are the social stigma that comes with the disorder. Stigmas that come with NSSI are statement such as the patient engages in self-harm for attention, or they are crazy – both which have been demonstrated to be false through numerous studies [1-3]. These statements and the social stigma that accompanies this disorder can be a difficult process on top of the emotions that led the patient to partake in NSSI in the first place. The trust in the patient-provider relationship needs to be strong with clear boundaries. The goal is for the patient not to feel any more shame but be released from it and see themselves in a new light – one where they can recover and attain their own personal mental and physical health goals [4]. Due to the overwhelming responsibility for the physician to understand and treat the entire patient, this particular article looks to clear the muddy waters surrounding NSSI, discuss how it can become an addiction, review the literature, discuss treatments and therapies, and provide key clinical pearls on building and maintaining relationships with patients afflicted by this disorder.

What is NSSI?

In this study, NSSI will be defined in a basic sense as the intentional physical harm of one’s body in order to cope with extreme emotion and referred to by the more specific term of Non-Suicidal Self Injury (NSSI). NSSI is a broad term and can encompass a number of potentially damaging and physically destructive behaviors ranging from self-poisoning, self-asphyxiation, and superficial intentional abrasion usually due to intolerable tension or secondary to anxious thoughts [5-9]. This intentional mutilation of one’s body is done to cause damage, and typically not done with the intent to commit suicide [5-9]. Many of those with NSSI addiction are likely to have co-morbid diagnosis of passive or active suicidal ideation and are roughly as likely to commit suicide as those with other process addiction disorders or substance use disorders [5-12]. Many medical and mental health experts attest that NSSI is the fastest growing issue with modern teenagers and this has been demonstrated through numerous reports in the medical, psychological, and nursing literature [5-9,13-17]. NSSI is also known by other terms such as self-mutilation [18,19] or Self-injurious Behavior Syndrome (SIBS) [20-22].

The most common methods of NSSI include the following:

- Cutting or stabbing with razors or other sharp objects

- Burning with objects like lighters, coals, cigars, and other hot objects

- Scratching skin to the point of extracting blood

- Biting oneself to the point of extracting blood

- Preventing the healing of wounds through picking

- Scalding hot shower

- Head Banging and other blunt traumatic injuries

While not all inclusive of the behaviors that have been demonstrated in those afflicted with NSSI behaviors, this list provides several examples of behaviors which have been studied at least at some depth by other research teams over the last several years [5-9,13-22]. These behaviors and other similar appearing injuries are important for the physician to note during an initial assessment and are ones that the astute physician may observe during the exposure portion of the initial physical examination.

Self-harm is not a diagnosis found in the DSM-5; however, Nonsuicidal Self-Injury (NSSI) falls under the category “Conditions for Further Study.” “Nonsuicidal self-injury most often starts in the early teens years and can continue for many years” [23]. When NSSI is a focus of treatment, clinicians give a V-code instead of a diagnosis for personal history of NSSI (V15.59). V-codes are not mental illnesses, but are identified as an issue demanding focus from the clinician. At this point, clinicians do not perceive NSSI as a mental illness, but instead a maladaptive coping strategy.

The proposed criteria in the DSM-5 for NSSI includes:

1) 5 or more days in the last year of intentional self-inflicted damage (NSSI) to one’s body.

2) One engages in NSSI to get relief from negative feelings or a negative cognitive state, to resolve interpersonal difficulty, or to induce a positive feeling state.

3) NSSI is associated with either interpersonal difficulties or negative feelings or thoughts occurring in a period before the self-injurious act; before engaging in the act, a period of preoccupation with the intended behavior that is difficult to control, thinking about NSSI that occurs frequently.

4) NSSI behavior is not socially sanctioned.

5) NSSI behavior/its consequences cause clinically significant distress or interference in interpersonal, academic, or other important areas of functioning.

6) NSSI behavior does not occur exclusively during psychotic episodes, delirium, substance intoxication, or substance withdrawal.

7) NSSI behavior is not part of a pattern of repetitive stereotypies with those with neurodevelopmental disorder.

8) The behavior is not better explained by another mental disorder or condition [23].

What is Addiction?

Addiction, while often related to the use of substances, has been demonstrated to involve more than what is classically defined by the layman or physician. Based on the currently understood neurobiopathophysiological mechanisms, addiction can be defined by three major phases as laid out by Koob and Volkow [24]. The first phase is the binge or intoxication phase in which the substance or action is partaken in to provide the euphoric release. The second phase is the withdrawal phase where the substance or action is stopped and the negative effects of stopping the substance or action begin to take effect. Finally, the preoccupation and anticipation phase where the behavior or substance of desire is brought to the forefront of the mind of the subject of interest leading them to again seek out the substance or behavior of interest.

As a secondary requirement to the cycle of behavior, inclusion for the classification of the behavior or substance as addictive include (1) the loss of control of actions in partaking in the substance or action, (2) Dysphoria or other negative emotional states when taking the substance or the behavior is prevented, and (3) the compulsion to seek out the substance or partake in the behavior must all be present [24-26].

Commonly cited behaviors and substances which are involved as addictions include:

- Opioids Medications

- Methamphetamines

- Cocaine and other stimulants

- Ethyl Alcohol

- Gambling

- Shopping

- Sexual Intercourse

- Pornographic Viewing

- Video Games

- Cellular Device Utilization

While again not all inclusive, these behaviors have all been found to interact within the brain’s natural dopaminergic circuitry, specifically the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, which starts in the pontine ventral tegmental region and stretches into the nucleus accumbens [27], and can lead to obsession and compulsive behaviors. All of these have been found in several studies, and through personal experiences of patients, to lead to damaged personal relationships and difficulties with maintaining basic adult activities of daily living (ADLs) [24-28].

Within the psychology literature, addiction, on top of the neurobiological mechanism reported above, includes a mental fixation, often referred to as an all-encompassing craving to ingest the substance or partake in the behavior and obsession with either the substance or the behavior to the point that it begins to damage the patient’s relationships with family and friends [29]. This fixation then leads to total personal involvement [30], wherein the entirety of the patient’s personality structure becomes built around the addiction (e.g. the smoker who stands outside in the freezing rain or the alcoholic whose only social activity is attendance at the local bar). Finally, the patient can develop a physical dependency [31], in which the removal of the stimulus leads to physical symptoms including but not limited to: anxiety, fatigue, sweating, vomiting, depression, seizures, and/or hallucinations. While many of the more severe symptoms are not included in the less physically taxing addictions, some case reports and other peer reviewed literature have demonstrated that they can produce severe withdrawal effects also [32-35].

Neurobiology of NSSI Addiction

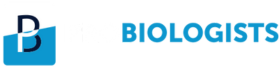

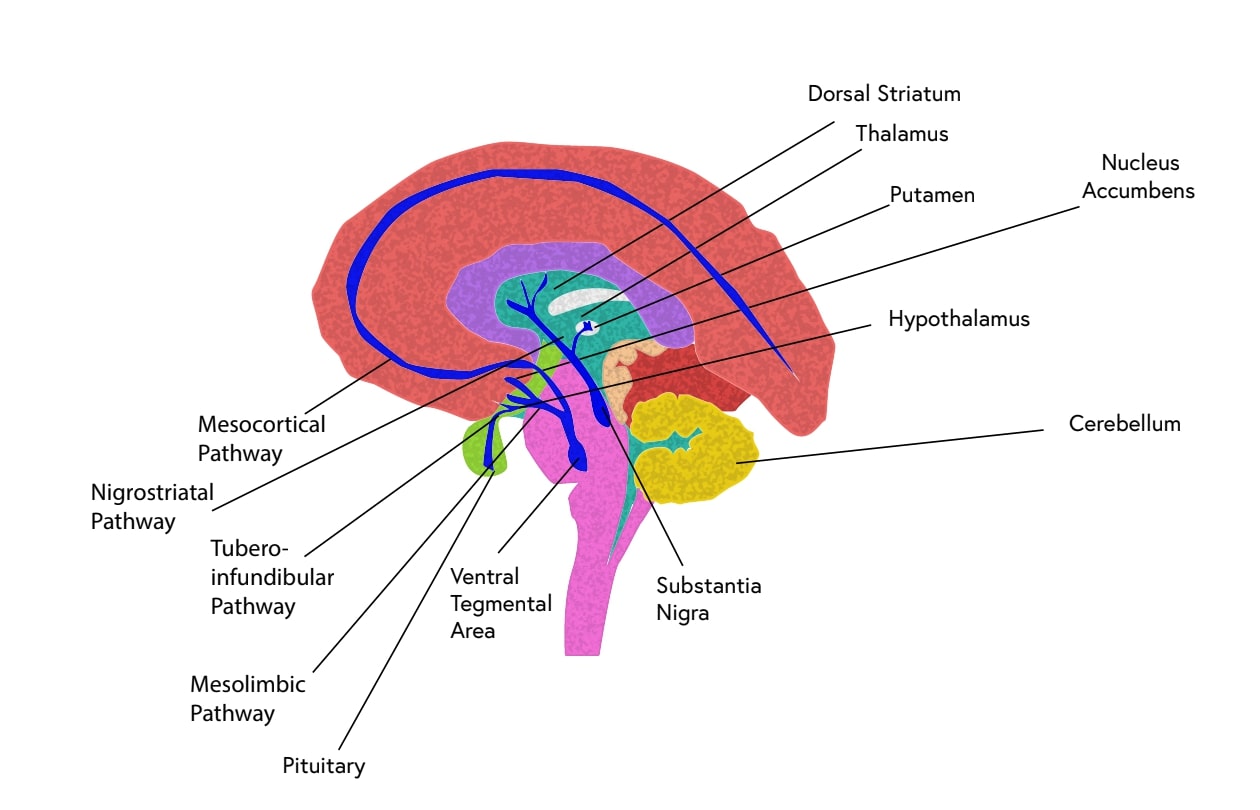

The basic neurobiology of NSSI addiction is similar in nature to that of any other addiction in that the mesolimbic dopaminergic pathway is activated during engagement with the activity. These major reward pathways, the mesocortical and mesolimbic dopaminergic pathways, are the ones demonstrated in Figure 1 and are utilized in normal physiological biology as the main method for driving the feeding, mating, and other basic day-to-day functions. The pathway begins in the ventral tegmental area of the pons and branches to the amygdala and then into the frontal lobe. These areas are the ones that are mainly affected by Process Addictions and/or Use disorders and demonstrate major neurobiological changes. In those individuals who suffer from use disorders secondary to alcohol, substances (Cocaine, Marijuana, Methamphetamines, Tobacco, etc.), or processes are present, the amygdala has been demonstrated on anatomical and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging to have an increase in size and activation and the frontal lobe has been demonstrated to have a decrease in size and activation (See Figure 2). These neurological changes and overactivation of the mesolimbic system leads to the psychological phenomena that are often described by the individuals who struggle with the disorders as “addiction” or “feeling like a junkie” where one feels the compulsion to continue the use of the substance or engage in the actions long after the euphoric effects no longer are experienced [36-39].

Figure 1: Demonstrated here are the dopamine pathways in the brain with the mesolimbic and mesocortical being the major dopamine pathways in the development of addictive behaviors.

Figure 2: A) Demonstrated here is a healthy normal brain B) Demonstrated here are the changes apparent in use disorders and process addictions with special attention given to decreased mass of the frontal lobe and increased mass of the amygdala.

Development of NSSI into Addiction

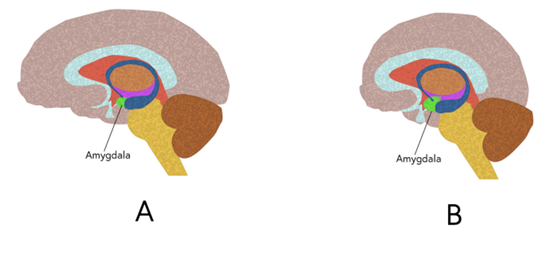

NSSI tends to begin early in life [40,41], whether that be late childhood or early adolescence and then continues into late adolescence or adulthood [40,41]. Just like addiction to substances or other process addictions like eating disorders, one who engages in NSSI tends to engage in order to become emotionally numb to uncomfortable emotions or intolerable memories [42]. With the act of NSSI, one is creating their own internal opioids through a subconscious psychological operation, engaging the dopaminergic and endogenous opioid systems within the central nervous systems [43]. Over time, those that participate in NSSI associate the physical pain of NSSI as a means to escape emotional pain [44]. Because of the release of emotions that accompanies the behavior, this repetitive action increases in both frequency and severity as the coping mechanism begins to create a self-feeding positive feedback loop [45]. This self-feeding positive feedback loop starts with the behavior itself, then the accompanying shame of having performed the action, followed by hiding the evidence of the behavior, followed by either external stimuli or increased shame from having performed the ritual of the self-mutilation which leads to the action of NSSI once again [45]. Like with other addictive behaviors or substances this cycle, often referred to as the shame cycle (Figure 3), continues to feed itself leading to further increases in both frequency and severity of the NSSI behaviors [46].

Figure 3: Above is a pictorial demonstration of the Shame Cycle.

Men and NSSI

Men’s mental health, throughout history, has been a taboo subject, due to the existence of “toxic masculinity”. Toxic masculinity for this article is defined as those cultural, group, and individual beliefs which prevent a man from being able to demonstrate emotional vulnerability, fear, anxiety, struggles with personal or professional difficulties, and/or reach out for help when struggling with personal or professional difficulties [47]. For this reason, it is only recently that research has been performed in this specific area of mental health. Mental health clinicians (whether physicians or clinical psychologists) are uncovering the seriousness and commonness of mental health disorders in men and adolescent boys. “Male and female prevalence rates of NSSI are closer to each other than in suicidal behavior disorder, in which the female-to-male ratio is about 3:1 or 4:1” [23].

In a study done from a Swiss prospective-longitudinal cohort study, adolescents were made up of 52% male participants at ages 13, 15, 17, and 20 [41] 27% of those participants reported participating in NSSI at least once. In males, the prevalence decreased from 12 to 5% over time. However, recurrence of NSSI increased after the age of 15. Less than half of adolescents utilized mental health services. Males reported using mental health services for externalizing problems, learning difficulties, and attention issues. The study noted that “males are at particular risk of not receiving adequate treatment for self-injury [NSSI]” [41]. This lower utilization of mental health services is at its core detrimental to the male psyche and has led to worse outcomes mentally, emotionally, and physically for these needy and suffering patients.

Co-Morbidity of NSSI Addiction and Other Addictions

Those who battle with NSSI addiction are at high risk for other process or substance addictions. The substance abused by those who participate in NSSI correlates to the reasoning they participate in NSSI [48-51]. For example, alcohol and opiates are the standard preference for those who participate in NSSI to escape emotions. Those who use NSSI as a method of stimulation would typically be seen using cocaine and amphetamines [48-51].

A recent meta-analysis by Cucchi et. al has found that 27.3% of individuals diagnosed with an Eating Disorder (ED) also report NSSI [52]. Lifetime estimates average 32.7% for bulimia nervosa, 21.8% for anorexia nervosa, and around 20% for binge eating disorder [52,53]. Dzombak et. al have reported a higher rate of NSSI behaviors in those who exhibit binging and purging behaviors versus restrictive eating behaviors [54]. Conversely, in an analysis by Wang et. al on undergraduate females, restrictive eating behaviors, had a higher association with NSSI [55]. Claes et. al has performed a similar study on males with eating disorders, finding that there was no significant difference between eating disorder subtypes and patients who displayed NSSI behaviors were likely to show significantly more severe ED symptoms and impulse-control problems than those who did not engage in NSSI [36]. Although the consensus is mixed on whether the subtype of eating disorder affects the likelihood of NSSI, the literature has generally found a significant association between the two addictions.

A possible common thread between these maladaptive behaviors is negative urgency. Negative urgency is a personality trait characterized by the tendency to act rashly in response to negative emotions. Negative urgency has been shown to be associated with the frequency of NSSI, variety of NSSI methods, years of NSSI, alcohol use disorder, and eating problems [53-56]. Fischer et. al [38] have concluded that the personality influence of negative urgency, when combined with learned, behavior-specific expectancies, can lead to the development of maladaptive addictive behaviors. This early data demonstrates that oftentimes patients suffering from other addictive behaviors often also struggle with NSSI tendencies.

NSSI Out of Perfectionism

NSSI can arise from a multitude of other disorders and behavioral tendencies and are often associated with negative self-image, use disorders, process addictions, eating disorders, and other psychiatric ailments. One of the most commonly found concurring disorders with NSSI is perfectionism or perfectionist behaviors. Perfectionism is when one strives to achieve flawlessness, in behavior and thoughts, which is seen to begin in children and young adults [57-59]. Whether this involves school, work, professional relationships, or social relationships, the end goal of perfect behavior can never be obtained by those suffering with this abnormal behavioral pattern. Perfectionism is a trait used to diagnose DSM-V disorders, like obsessive-compulsive and eating disorders. Oftentimes, failure to meet the perfectionist’s standards or goals leads to maladaptive behaviors through psychological pre-meditation and eventually physical acting out [58]. Similar to the obsessive-compulsive disorders, there is a common point of anxiety for making mistakes and the failure of their results [58]. The shame cycle is correlative to the acting out of maladaptive perfectionism. Claes and Soenens elaborated that NSSI stems from shame or the lack of control of their situation [58]. These sources of shame and lack of control can stem from: abuse, familial expectations, educational strain, career demands, societal perception, self-doubt, and organization desires [57-60]. As seen with other causes of NSSI, those struggling with perfectionistic tendencies treat the action of NSSI as a punishment and coping mechanism which activates the release of dopamine.

NSSI and Depression

Of those potential causes of patient’s reliance on NSSI as a coping mechanism of the biggest risk factors for the development of NSSI addiction is that of depression, anxiety, or bipolar disorder. Patients suffering from the mental health conditions of depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder are well documented to have co-morbid NSSI addiction [61-68]. Those patients who suffer with these mood disorders can often find themselves engaging in the addictive process to decrease the negative affective aspects of the disorders [61-68]. Therefore, as with the management of the other causes of NSSI addiction, it is key that the clinician as the key questions and perform the most thorough physical examination in order to determine what can be done for the betterment of the patient.

Evaluation: History and Physical Exam

When working with patients who participate in NSSI some key details to remember as clinicians is to approach the patient without statements or blame on the behavior. While the emotive feelings of uncomfortableness with the injuries and the behavior can bring even the most expert clinician or surgeon discomfort and cognitive dissonance, the patient is suffering and needs help. This focus of the needs of the patient must remain the main focus of the clinician - working in a therapeutic relationship to decrease the suffering of the needy and deserving patient. Major things to consider when talking with the patient is to address the main reason for the patient’s arrival within the clinical space in a non-judgmental tone of voice and with caring and empathetic language. Questions about the injuries should not focus on blame or shame, but instead on the method of injury, cleanliness of the wound, and the depth of the injury. Questions should also encompass social support, comorbid conditions such as use disorders and other process addictions. Finally, a full and thorough physical examination including full exposure of the extremities, torso, chest wall, and upper thighs, and arms should be included. Key clinical pearls include:

- Those who NSSI tend to wear loose clothing and covering clothes to conceal their wounds.

- The majority of the wounds are on easy to cover up regions such as the inside of the Upper arms and Upper thighs.

- Self-injurious behavior can often progress just like addiction does and, as a result, early intervention is key.

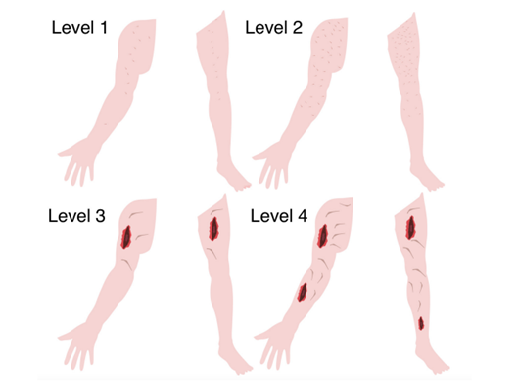

- A diagram of the severity and frequency is included here with a new set of associated levels based on the physical examination (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4: New way to measure severity of NSSI based on the physical examination.

Level 1: Not Frequent Not Severe - Injuries on the upper arm (Inner and outer) or upper thighs (Inner and outer) - Not deep

Level 2: Frequent but Not Severe - Injuries on the upper arm and upper thighs moving to sides and down the arms and legs - Not deep

Level 3: Not Frequent but Severe - Injuries on the upper arm or upper thighs - Deep injuries. NB: May need Stitches and Wound Care

Level 4: Frequent and Severe - Injuries on the upper arm and upper thighs moving to sides and down the arms and legs - Deep - NB: May need Stitches and Wound Care and Increased Risk of Non-intentional Suicide.

- Future research directions include determining differences in treatment modalities between the four new levels of NSSI and what can be done in order to prevent potential worsening of symptoms from either a therapy, medication, or combination treatment modality standpoint.

In the clinical evaluation of a patient in regards to NSSI, it is additionally imperative to take into account the age, kind of NSSI, and ascertain the medical history. Firstly, a topic not so touched upon is the presentation and evaluation of NSSI in pre-adolescent individuals. For instance, it is to be noted that a child is unlikely to openly express concern about their own NSSI behaviors, whereas, an adult seeking help for NSSI might. In addition, the means in which the verbal evaluation should be conducted is also slightly different, as their linguistic ability to self-report may not be fully developed yet [69]. Techniques used to garner the presence and degree of NSSI entails the careful wording of the questions asked as to not lead the patient into a certain response and using a staggered approach in the evaluation of the patient as to not overwhelm them [69]. An approach here that spans multiple different sources is additionally imperative to assess the condition of the patient most accurately; a key manner in which to achieve this is to utilize the caregivers of the patient to gain, explain, and confirm information obtained in the evaluation [70]. It is to be mentioned here that establishing a sense of confidentiality and trustability with the child is especially important as to ease anxieties, potential fears of reprimanding, self-preservation due to a pattern of abuse, etc. In the elderly, the evaluation is yet again nuanced to fit the etiology and general commonalities in the group: chronic pain and isolationism are some of the more prevalent ones [71,72]. In addition, in older adults, the most common form of NSSI (48% of all cases) is through overdose, so one should bear in mind that an inconspicuous physical exam in this subset is not always indicative of an absence of the diagnosis [73].

History is also a key indicator of the evaluation of the patient. In the geriatric population, it is reported that an astounding “90% of older adults who die from suicide had diagnosable mental disorders at the time of death”, meaning that a history of mental (or physical) illness may provide further indications of a diagnosis in the evaluation [70].

Treatment and Therapies

Due to the nature of the disorder and the key requirements for clinicians and therapists to act, listed here are a small list of available treatment modalities. While not a full list, this primer level of introduction to therapeutics provides for the clinician an idea of what can and should be utilized for the betterment of the patient. Using one of these or a combination approach, the end goal of either harm reduction or complete cessation can be reached with the majority of the patients being treated in the outpatient over a longer period of time when intensive inpatient care is no longer deemed necessary [74].

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a psychotherapeutic method that focuses on how core beliefs affect thoughts, thoughts affect actions, which leads to consequences. This method is effective for NSSI because it focuses on what causes the person to feel the need to engage in NSSI [69]. As mentioned above, people have several different motives on why they engage in NSSI. It can be to feel something, to punish themselves, to express emotions, or to gain control. CBT can help shift their initial negative, unrealistic core beliefs to healthy realistic ones. If the person has a core belief that they are a failure for various reasons, CBT will help them break down what leads them to believe them about themselves. Once that has been discovered, the counselor can guide the person to think more rationally about themselves [75]. For example, a patient discloses they feel they are a failure because they did not want to go to college. The patient’s parents helped developed this core belief by telling the patient they are dumb for not going to college. The counselor could challenge that thought by putting it into perspective. The counselor could ask the patient if they believe that everyone that chooses not to go to college is a failure? This can lead to further discussion of the patient’s distorted view of themselves. That they are not a failure if they choose not to go to college and can have a successful career without going to college or going later in life. That the patient’s view is irrational because it is not consistent with everyone else who chose not to go to college. This would be the beginning of using CBT to challenge the patient’s irrational thoughts and helping them gain a better understanding of themselves.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a newer age therapy technique that focuses on not avoiding the big feelings that a person has. They face the feelings head on and accept them for what they are: a thought. It trains the person not to ponder or overthink it. They understand the thought, accept it, and move on in the present moment [76]. They make a commitment to focus on the future at hand and not let their thoughts hold them down. ACT is a successful therapy for NSSI addiction, as it allows the patient to recognize the feelings they have and, yet, not let it lead to participation in NSSI. In most cases, pondering on the thoughts of insufficiency or hopelessness is what leads to the actions of NSSI. If the person can part ways with the idea of making those thoughts more than what they are, they can navigate through the emotions they experience [73]. Being able to manage those emotions can decrease the feelings of wanting to participate in NSSI. The patient can learn that the mind has millions of thoughts on a daily basis and learning to accept these emotions are valid and navigate through these negative emotions can release the tension they feel [73]. They can accept they have certain thoughts, while understanding they do not have to dictate their lifestyle or lead them to participate in NSSI. Once the patient can come to that realization, it will promote emotional regulation and growth in mental wellness of self-esteem.

Medication Management

While there is not a specific pharmacological agent that is utilized for the management of NSSI, there are some medications used to help disorders that could lead some to engage in NSSI. In most cases, people who are more likely to partake in NSSI have disorders that have the symptom of impulsivity: such as borderline personality disorders and eating disorders [77]. NSSI behaviors are frequent in people who fall under major depressive disorders and bipolar disorder. Due to treating the underlying condition, numerous studies show that certain medications that help these disorders can be effective in helping with the cravings to NSSI [77]. Some antidepressants have shown effectiveness in decreasing NSSI. Since antidepressants focus on increasing the chemicals in the brain to help with mood stabilization, it can help the patient not feel the need to participate in NSSI. If they have a balance of chemicals in the brain, they could no longer have the triggering emotions that lead to NSSI. Opioid antagonists are another medication that has shown a decrease of NSSI behaviors when taken. As stated before, NSSI is an addiction because it releases dopamine when engaging in it. The main use of opioid antagonists is to help people who are addicted to opiates wean off of them. Engaging in NSSI gives off the same feeling and chemicals of someone who is actively using opiates [77]. The use of opioid antagonists in patients who participate in NSSI is to help them wean off the cravings of NSSI. It gives the body a small amount of the dopamine feeling so the patient can feel less of the need to get that feeling through an NSSI episode. Studies have shown that taking opiate antagonists has made a significant decrease in patients who participate in NSSI [77].

Conclusion

When treating a patient with NSSI addiction, it is vital to understand the aforementioned shame cycle that patients struggling with Substance-Use disorders or other forms of addictions may be trapped within. The patient continues to suffer from the shame of the addictive behavior, in this case NSSI, and believes that this behavior is a result of their own “defectiveness”. They recognize this behavior as a means to alleviate some of their intolerable feelings - whether this is anxiety, grief, or other negative emotions. As a result, they act out and participate once again in their addictive behavior, in this case the resulting NSSI. This then leads to an increase in the initial shame which accompanied NSSI from a prior episode [45]. It is an ongoing and vicious cycle.

It is the authorial team’s strongest recommendation that shame inducing language not be utilized by the provider - this is a disease much like that of cancer. No patient with cancer is bad for having cancer and to suggest such would in and of itself be counter-intuitive to the proper and quality treatment of the patient seeking help. The use of colloquialisms or shaming inducing language can and will play further into the patient’s own shame cycle leading to further harm. Instead, when discussing the patient’s disorder, it is imperative to separate the patient’s disease from the patient themselves. Through this painstaking effort from the physician will they be able to actually help the suffering patient.

In cases of NSSI, it comes with a lot of shame and guilt. That is why it is important more than ever to come to the patient with an unbiased opinion and a neutral stance. If the patient feels judgment or contempt from the physician or counselor, they could retreat back into their shame. Once the patient sees the physician or counselor as unsafe, it will be difficult for the patient to reach that point again. This could hinder their healing journey and lead to more damage. Building rapport with the patient will be the key to getting the depth needed to help with the feelings of wanting to participate in NSSI [78,79]. The patient is in need of a safe place to get out the strong emotions they had held in for a while. For the moment, their way of coping was through NSSI and it is the care team’s job to help them find a different outlet. Stigmas that come with NSSI are statement such as the patient engages in self-harm for attention, or they are crazy – both which have been demonstrated to be false through numerous studies [1-3]. These statements and the social stigma that accompanies this disorder can be a difficult process on top of the emotions that led the patient to partake in NSSI in the first place. The trust in the patient-provider relationship needs to be strong with clear boundaries. The goal is for the patient not to feel any more shame but be released from it and see themselves in a new light – one where they can recover and attain their own personal mental and physical health goals [4].

Secondarily, the patients who suffer from NSSI disorders present secondary to injuries which were too worrisome to ignore or because of other conditions which are affecting their health. During these encounters, the patients both demonstrate a trust of the provider and can demonstrate hesitancy to disclose their condition due to the perceived power differential of provider over patient. In these moments it is key that the patient’s trust not be abused, verbiage being utilized to indicate how serious and important the NSSI is to the patient’s health, and how the provider is there only to collaborate with the patient for their long term wellbeing and desired health goals. Finally, and most importantly, the patient by nature of coming for help, trusts their doctor implicitly [69], therefore it is key that the physician take this trust and responsibly to act towards the benefit of the patient [78].

References

2. Wilcox HC, Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Vincent KB, Pinchevsky GM, O'Grady KE. Longitudinal predictors of past-year non-suicidal self-injury and motives among college students. Psychological Medicine. 2012 Apr;42(4):717-26..

3. Power J, Brown SL, Usher AM. Non-suicidal self-injury in women offenders: motivations, emotions, and precipitating events. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health. 2013 Jul 1;12(3):192-204.

4. Bean RA, Keenan BH, Fox C. Treatment of Adolescent Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: A Review of Family Factors and Family Therapy. The American Journal of Family Therapy. 2022 Apr 21;50(3):264-79.

5. Skegg K. Self-harm. The Lancet. 2005 Oct 22; 366(9495):1471-83.

6. Laye-Gindhu A, Schonert-Reichl KA. Nonsuicidal self-harm among community adolescents: Understanding the “whats” and “whys” of self-harm. Journal of youth and Adolescence. 2005 Oct; 34(5):447-57.

7. Pattison EM, Kahan J. The deliberate self-harm syndrome. The American journal of psychiatry. 1983 Jul;140(7):867-72.

8. Hawton K, Saunders KE, O'Connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. The Lancet. 2012 Jun 23;379(9834):2373-82.

9. McAllister M. Multiple meanings of self harm: A critical review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2003 Sep;12(3):177-85.

10. Horváth LO, Győri D, Komáromy D, Mészáros G, Szentiványi D, Balázs J. Nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide: the role of life events in clinical and non-clinical populations of adolescents. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020 May 6;11:370.

11. Poudel A, Lamichhane A, Magar KR, Khanal GP. Non suicidal self injury and suicidal behavior among adolescents: co-occurrence and associated risk factors. BMC Psychiatry. 2022 Dec;22(1):1-2.

12. Herzog S, Choo TH, Galfalvy H, Mann JJ, Stanley BH. Effect of non-suicidal self-injury on suicidal ideation: real-time monitoring study. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2022:1-3.

13. O'Connor RC, Rasmussen S, Miles J, Hawton K. Self-harm in adolescents: self-report survey in schools in Scotland. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009 Jan;194(1):68-72.

14. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK. Self-harm: longer-term management. British Psychological Society.

15. Jeffery D, Warm A. A study of service providers' understanding of self-harm. Journal of Mental Health. 2002 Jan 1;11(3):295-303.

16. Ougrin D, Tranah T, Leigh E, Taylor L, Asarnow JR. Practitioner review: Self-harm in adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012 Apr;53(4):337-50.

17. McAllister M, Creedy D, Moyle W, Farrugia C. Nurses' attitudes towards clients who self-harm. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002 Dec;40(5):578-86.

18. Walsh BW, Rosen PM. Self-mutilation: Theory, research, and treatment. Guilford Press; 1988.

19. Feldman MD. The challenge of self-mutilation: A review. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1988 May 1;29(3):252-69.

20. Huisman S, Mulder P, Kuijk J, Kerstholt M, van Eeghen A, Leenders A, et al. Self-injurious behavior. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2018 Jan 1;84:483-91.

21. Claes L, Vandereycken W. Self-injurious behavior: differential diagnosis and functional differentiation. ComprehensiveP. 2007 Mar 1;48(2):137-44.

22. Favazza AR. Self-injurious behavior in college students. Pediatrics. 2006 Jun 1;117(6):2283-4.

23. American Psychiatric Association DS, American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013 May.

24. Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010 Jan;35(1):217-38.

25. Goodman A. Addiction: definition and implications. British Journal of Addiction. 1990 Nov;85(11):1403-8.

26. Feltenstein MW, See RE. The neurocircuitry of addiction: an overview. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2008 May;154(2):261-74.

27. Powledge TM. Addiction and the brain: The dopamine pathway is helping researchers find their way through the addiction maze. Bioscience. 1999 Jul 1;49(7):513-9.

28. Koob GF, Sanna PP, Bloom FE. Neuroscience of addiction. Neuron. 1998 Sep 1;21(3):467-76.

29. Alcaro A, Brennan A, Conversi D. The SEEKING drive and its fixation: A neuro-psycho-evolutionary approach to the pathology of addiction. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2021 Aug 12.

30. Cancrini L. The psychopathology of drug addiction: a review. Journal of Drug Issues. 1994 Oct;24(4):597-622.

31. Heit HA. Addiction, physical dependence, and tolerance: precise definitions to help clinicians evaluate and treat chronic pain patients. Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy. 2003 Jan 1;17(1):15-29.

32. Eide TA, Aarestad SH, Andreassen CS, Bilder RM, Pallesen S. Smartphone restriction and its effect on subjective withdrawal related scores. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018 Aug 13;9:1444.

33. Rosenberg KP, Carnes P, O'Connor S. Evaluation and treatment of sex addiction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2014 Mar 1;40(2):77-91.

34. Rosenthal RJ, Lesieur HR. Self-Reported Withdrawal Symptoms and Pathological Cambling. American Journal on Addictions. 1992 Jan 1;1(2):150-4.

35. Cunningham‐Williams RM, Gattis MN, Dore PM, Shi P, Spitznagel Jr EL. Towards DSM‐V: considering other withdrawal‐like symptoms of pathological gambling disorder. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2009 Mar;18(1):13-22.

36. Claes L, Jiménez‐Murcia S, Agüera Z, Castro R, Sánchez I, Menchón JM et al. Male eating disorder patients with and without non‐suicidal self‐injury: A comparison of psychopathological and personality features. European Eating Disorders Review. 2012 Jul;20(4):335-8.

37. Dir AL, Karyadi K, Cyders MA. The uniqueness of negative urgency as a common risk factor for self-harm behaviors, alcohol consumption, and eating problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2013 May 1;38(5):2158-62.

38. Fischer S, Settles R, Collins B, Gunn R, Smith GT. The role of negative urgency and expectancies in problem drinking and disordered eating: testing a model of comorbidity in pathological and at-risk samples. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012 Mar;26(1):112.

39. Glenn CR, Klonsky ED. A multimethod analysis of impulsivity in nonsuicidal self-injury. Personality disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2010 Jan;1(1):67-75.

40. Hawton K, Saunders KE, O'Connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. The Lancet. 2012 Jun 23;379(9834):2373-82.

41. Steinhoff A, Ribeaud D, Kupferschmid S, Raible-Destan N, Quednow BB, Hepp U, et al. Self-injury from early adolescence to early adulthood: age-related course, recurrence, and services use in males and females from the community. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2021 Jun;30(6):937-51.

42. Loughrey G, Kerr A. Motivation in deliberate self-harm. The Ulster Medical Journal. 1989 Apr;58(1):46.

43. Unterwald EM, Zukin RS. The endogenous opioidergic systems. InOpioids, bulimia, and alcohol abuse & alcoholism 1990 (pp. 49-72). Springer, New York, NY.

44. Guerreiro DF, Cruz D, Frasquilho D, Santos JC, Figueira ML, Sampaio D. Association between deliberate self-harm and coping in adolescents: a critical review of the last 10 years' literature. Archives of Suicide Research. 2013 Apr 1;17(2):91-105.

45. Gordon KH, Selby EA, Anestis MD, Bender TW, Witte TK, Braithwaite S, et al. The reinforcing properties of repeated deliberate self-harm. Archives of Suicide Research. 2010 Nov 9;14(4):329-41.

46. Owens C, Hansford L, Sharkey S, Ford T. Needs and fears of young people presenting at accident and emergency department following an act of self-harm: secondary analysis of qualitative data. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2016 Mar;208(3):286-91.

47. Chandler A. Boys don’t cry? Critical phenomenology, self-harm and suicide. The Sociological Review. 2019 Nov;67(6):1350-66.

48. Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: positive and negative urgency. Psychological bulletin. 2008 Nov;134(6):807.

49. Draps M, Sescousse G, Potenza MN, Marchewka A, Duda A, Lew-Starowicz M, et al. Gray matter volume differences in impulse control and addictive disorders-an evidence from a sample of heterosexual males. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2020 Sep 1;17(9):1761-9.

50. Hooley JM, Dahlgren MK, Best SG, Gonenc A, Gruber SA. Decreased amygdalar activation to NSSI-stimuli in people who engage in NSSI: A neuroimaging pilot study. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020 Apr 2;11:238.

51. Huang X, Rootes-Murdy K, Bastidas DM, Nee DE, Franklin JC. Brain differences associated with self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Scientific Reports. 2020 Feb 12;10(1):1-3.

52. Cucchi A, Ryan D, Konstantakopoulos G, Stroumpa S, Kaçar AŞ, Renshaw S, et al. Lifetime prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury in patients with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2016 May;46(7):1345-58.

53. Islam MA, Steiger H, Jimenez‐Murcia S, Israel M, Granero R, Agüera Z, et al. Non‐suicidal self‐injury in different eating disorder types: Relevance of personality traits and gender. European Eating Disorders Review. 2015 Nov;23(6):553-60.

54. Dzombak JW, Haynos AF, Rienecke RD, Van Huysse JL. Brief report: Differences in nonsuicidal self-injury according to binge eating and purging status in an adolescent sample seeking eating disorder treatment. Eating Behaviors. 2020 Apr 1;37:101389.

55. Wang SB, Pisetsky EM, Skutch JM, Fruzzetti AE, Haynos AF. Restrictive eating and nonsuicidal self-injury in a nonclinical sample: Co-occurrence and associations with emotion dysregulation and interpersonal problems. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2018 Apr 1;82:128-32.

56. Schreiner MW, Mueller BA, Klimes-Dougan B, Begnel ED, Fiecas M, Hill D, et al. White matter microstructure in adolescents and young adults with non-suicidal self-injury. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2019;10.

57. Frost RO, Marten P, Lahart C, Rosenblate R. The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive therapy and research. 1990 Oct;14(5):449-68.

58. Gyori D, Balazs J. Nonsuicidal self-injury and perfectionism: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021:1076.

59. Flett GL, Goldstein AL, Hewitt PL, Wekerle C. Predictors of deliberate self-harm behavior among emerging adolescents: An initial test of a self-punitiveness model. Current Psychology. 2012 Mar;31(1):49-64.

60. Klonsky ED. The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007 Mar 1;27(2):226-39.

61. Cook NE, Gorraiz M. Dialectical behavior therapy for nonsuicidal self‐injury and depression among adolescents: Preliminary meta‐analytic evidence. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2016 May;21(2):81-9.

62. Wilkinson P, Kelvin R, Roberts C, Dubicka B, Goodyer I. Clinical and psychosocial predictors of suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the Adolescent Depression Antidepressants and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT). American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011 May;168(5):495-501.

63. Baetens I, Claes L, Hasking P, Smits D, Grietens H, Onghena P, et al. The relationship between parental expressed emotions and non-suicidal self-injury: The mediating roles of self-criticism and depression. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015 Feb;24(2):491-8.

64. Chartrand H, Sareen J, Toews M, Bolton JM. Suicide attempts versus nonsuicidal self-injury among individuals with anxiety disorders in a nationally representative sample. Depression and Anxiety. 2012 Mar;29(3):172-9..

65. Peters EM, Bowen R, Balbuena L. Mood instability contributes to impulsivity, non‐suicidal self‐injury, and binge eating/purging in people with anxiety disorders. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 2019 Sep;92(3):422-38.

66. Esposito-Smythers C, Goldstein T, Birmaher B, Goldstein B, Hunt J, Ryan N, et al. Clinical and psychosocial correlates of non-suicidal self-injury within a sample of children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010 Sep 1;125(1-3):89-97.

67. MacPherson HA, Weinstein SM, West AE. Non-suicidal self-injury in pediatric bipolar disorder: clinical correlates and impact on psychosocial treatment outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2018 May;46(4):857-70.

68. Masi G, Lupetti I, D’acunto G, Milone A, Fabiani D, Madonia U, et al. A comparison between severe suicidality and nonsuicidal self-injury behaviors in bipolar adolescents referred to a psychiatric emergency unit. Brain Sciences. 2021 Jun;11(6):790.

69. Kao AC, Green DC, Davis NA, Koplan JP, Cleary PD. Patients' trust in their physicians: effects of choice, continuity, and payment method. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1998 Oct;13(10):681-6.

70. Schmutte T, Olfson M, Xie M, Marcus SC. Deliberate self‐harm in older adults: A national analysis of US emergency department visits and follow‐up care. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2019 Jul;34(7):1058-69.

71. Obeid JS, Dahne J, Christensen S, Howard S, Crawford T, Frey LJ, Stecker T, Bunnell BE. Identifying and predicting intentional self-harm in electronic health record clinical notes: deep learning approach. JMIR Medical Informatics. 2020 Jul 30;8(7):e17784.

72. Srinath S, Jacob P, Sharma E, Gautam A. Clinical practice guidelines for assessment of children and adolescents. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2019 Jan;61(Suppl 2):158.

73. "Self Harm in Their Older Patients." Australian Journal of General Practice. https://www1.racgp.org.au/ajgp/2018/march/self-harm-in-their-older-patients.

74. Turner BJ, Austin SB, Chapman AL. Treating nonsuicidal self-injury: a systematic review of psychological and pharmacological interventions. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2014 Nov;59(11):576-85.

75. Raj. M AJ, Kumaraiah V, Bhide AV. Cognitive‐behavioural intervention in deliberate self‐harm. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2001 Nov;104(5):340-5.

76. Razzaque R. An acceptance and commitment therapy based protocol for the management of acute self-harm and violence in severe mental illness. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care. 2013 Aug;9(2):72-6.

77. Smith BD. Self-mutilation and pharmacotherapy. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005 Oct 1;2(10):28.

78. Classen DC, Kilbridge PM. The roles and responsibility of physicians to improve patient safety within health care delivery systems. Academic Medicine. 2002 Oct 1;77(10):963-72.

79. Sharpley CF, Heyne DA. Counsellor communicative control and client-perceived rapport. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 1993 Jul 1;6(3):171-81.