Abstract

Post-mastectomy pain syndrome (PMPS) is a recognized problem associated with functional disability. It is defined as pain in the anterior or lateral region of thorax, axilla, and/or medial upper arm after surgery without infection or tumor recurrence. The aim of this study is to analyze the disability associated with pain, to identify and describe the characteristics of pain at different stages after breast cancer surgery in a sample of women referred to a Rehabilitation Unit.

Method: Single-center retrospective observational study. Pain perception was categorized according to predominant type (neuropathic, musculoskeletal, or related to lymphatic dysfunction). Disability was assessed using Quick Dash score.

Statistical analysis: Descriptive study of the sample, Spearman’s non-linear correlation was used to check the association between ordinal and qualitative variables and Linear logistic regression was performed to test the influence of variables on pain and disability perception.

Results: 128 women, 23.06% of the total sample, had PMPS. Mean age: 57.12; Mean BMI:27.05. The most common cause of pain was neuropathic. Mean Quick Dash score: 49.26.

There was moderate correlation between BMI and Quick Dash: R=0.182; p: 0.049; and between time elapsed since surgery and our assessment (rs = 0.31) for feeling pain. There was a low correlation between BMI (rs = 0.17), age (rs = 0.14) and pain, low negative correlation between surgery (rs = -0.27) and radiotherapy (rs = -0.09). There was a very low correlation between chemotherapy and perceived disability (rs = 0.16) and a very low negative correlation between perceived disability and use of radiotherapy (rs = -0.13).

Conclusions: Among women treated for breast cancer, neuropathic pain is the most common, but characteristics aren’t related to the level of disability. Surgical techniques, radiotherapy, older age, and high BMI predispose to PMPS. Time since surgery and high BMI predispose to high levels of disability.

Keywords

Post-mastectomy pain syndrome, Disability, Quick Dash score, Breast cancer

Introduction

Pain after breast cancer surgery or Postmastectomy pain syndrome (PMPS) is a well-recognized problem associated with functional impairment. It is defined as pain on the anterior or lateral region of thorax, axilla and/or medial upper arm after surgery without infection or tumor recurrence. Moderate to severe persistent pain affecting 15% to 60% of women at 1 year from surgery [1,2] generating disability and poor quality of life [3]. Pain perception consists in burning pain, shooting pain, pressure sensation, or numbness. Etiology is probably multifactorial and may involve peripheral as well as spinal and supraspinal structures. Several authors conclude that the most important factors related with breast pain after surgery are axillary lymph node dissection, more severe acute postoperative pain intensity, preoperative pain in the operative area, younger age, and radiotherapy [1,2].

The purpose of this study is to analyze the disability related with pain, identify, and describe the characteristics of pain in different stages after breast cancer surgery in a sample of women referred to a Rehabilitation Unit over a period of 4 years. Thinking and recognizing it could help to prevent it and start optimal management.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Women who were referred to the "lymphoedema consultation" of the Rehabilitation Service of Doctor Peset Hospital, an university hospital in Valencia, Spain.

Procedure

Data collection over four calendar years (January 2019 to August 2023) of women with breast surgery regardless of surgery type: lumpectomy or mastectomy, axillary node resection or sentinel node resection. Patients with bilateral tumor involvement, cases of tumor recurrence, patients referred by non-oncologic breast surgery, disability without pain and breast tumor surgery on men, are not included in the study.

Method

Retrospective observational unicentric study over women with disability caused by pain on breast, axillary or thoracic region after breast oncological treatment.

Data collection included the following sections:

- Sociodemographic assessment: age, manipulative dominance, and sport habit.

- Oncological treatment included: surgical technical (Conservative surgical, Mastectomy with or without Sentinel lymph node biopsy or Lymph Node Surgery), radiotherapy (yes or not), type of hormone therapy and chemotherapy.

- Protocolized clinical assessment: Body Mass Index (BMI), inspection and palpation of both upper extremities (UE), shoulder girdle and pectoral-breast area, joint shoulder balance, sensitive examination, muscle balance, and undirected volumetric of both upper limbs obtained from circometric measurements of UE for determination of lymphedema presence.

- Recording of pain: Pain perception has been categorized according to the predominant nature (neuropathic, musculoskeletal, or related to lymphatic dysfunction).

- Disability Assessment: Quick Dash score assessed at the time of clinical assessment [4,5].

Statistical analysis

- Descriptive study of the sample using mean and standard deviation statistics for quantitative variables, and absolute and relative frequency for qualitative variables.

- Distributions of continuous outcomes of interest (Quick Dash score, delay between surgical and clinical consulting) were investigated to determinate normal distribution. Then, we studied Pearson bivariate correlation.

- Spearman’s non-linear correlation was used to check the possible association between ordinal variables and qualitative variables. In this case we categorized the delay between surgery and assessment in five groups: 0-12 weeks; >12-24 weeks; >24-36 weeks; >36-48 weeks and >48 weeks. Also, Quick Dash score has been categorized in four groups: Low disability (0-25), moderate disability (26-50), great disability (51-75), and extreme disability (76-100). Qualitative variables included physical habits, nature of pain, and oncological treatments.

- Linear logistic regression was performed to test the influence of variables for pain and disability perception.

PSPP 1.4.0 [6] was used for statistical processing (access free). The degree of significance was considered for p= 0.05.

The study complies with the ethical regulations on biomedical research involving human subjects, so it has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Doctor Peset Universitary Hospital (Code Number CEIm: 23/096).

Results

Between January 2019 and August 2023, 555 patients were referred to our Rehabilitation unit of which 128 (23,06%) accomplished inclusion criteria.

Descriptive analysis results

Sociodemographic results: The mean age of the sample was 57.12 years (31-89 years; SD 12.97).

The upper limb of manipulative dominance was right arm in 89.1% of cases (114 patients) and in 57.8% of cases (74 patients) the affected side was the left side. Regarding sport habit, 57.1% of the sample (73 patients) performed some activity, either mild aerobic exercise (29 patients) or moderate-intense exercise in gym (44 patients).

Oncological treatment results: In 30.5% of cases, axillary dissection was performed (66 patients), and 88.3% received radiotherapy (113 patients) with 40.29Gy median doses, between 26 and 53.35Gy.

One hundred and five patients (82.03%) received hormone therapy, and 71 patients received adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy (55.46%); anthracyclines, cyclophosphamide, and taxanes have been the most common option.

Table 1 shows descriptive data about therapeutic procedures.

|

TREATMENTS |

Number & (%) |

||

|

BREAST SURGERY (n=128) |

CS + SLNB |

54 (42.2) |

|

|

CS + LNS |

36 (28.1) |

||

|

Mastectomy + SLNB |

8 (6.3) |

||

|

Mastecyomy + LNS |

30 (23.4) |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

RADIOTHERAPY (n=113) |

Yes |

113 (89.7) |

|

|

No |

13 (10.3) |

||

|

Missing |

2 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

HORMONAL THERAPY (n=104) |

Tamoxifen |

46 (44.2) |

|

|

Aromatase inhibitors |

Non steroidal |

45 (43,3) |

|

|

Steroidal |

5 (4,8) |

||

|

Combination HT |

8 (7.7) |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHEMOTHERAPY (n=71) |

ACT |

32 (45.1) |

|

|

ACT + M |

16 (22.5) |

||

|

Combinations without M |

13 (18.3) |

||

|

Combinations + M |

10 (14.1) |

||

|

CS: Conservative Surgical; SLNB: Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy; LNS: Lymph Node Surgery; RT: Radiotherapy; T: Tamoxifen; Ar Inh: Aromatase Inhibitors; A: Anthracyclines; C: Cyclophosphamide; T: Taxane; M: Monoclonal Antibodies |

|||

Clinical assessment results: Women have been referred to Rehabilitation Unit since surgery at mean time of 34.64 weeks. (SD: 77.85; median: 12 weeks).

The mean BMI was 27.05 kg/m2 (17.67 – 40.48; SD: 5.34). No skin alterations were detected on inspection in 86.6% of cases (107 patients), while 14.8% (19 patients) showed radiotherapy dermatitis; 47.7% of the cases (61 patients) showed some scar sensitive alterations (dysesthesia, hyperalgesia), spontaneously or on palpation scar, with or without adhesion to deep tissues.

91.4% of the cases (117 patients) had no clinical signs of lymphoedema according to the International Society of Lymphology classification [7] (subclinical stage), 7% (9 patients) were classified as stage 2, and two patients (1,6%) were considered upper limb stage 2A.

Sensory examination showed some alteration in the affected limb in 50.1% of the cases (64 patients), with a predominance of hypoalgesia in the posterior area of the upper arm. In addition, 7% of the patients (9 patients) had severe chemotherapy-related neuropathy.

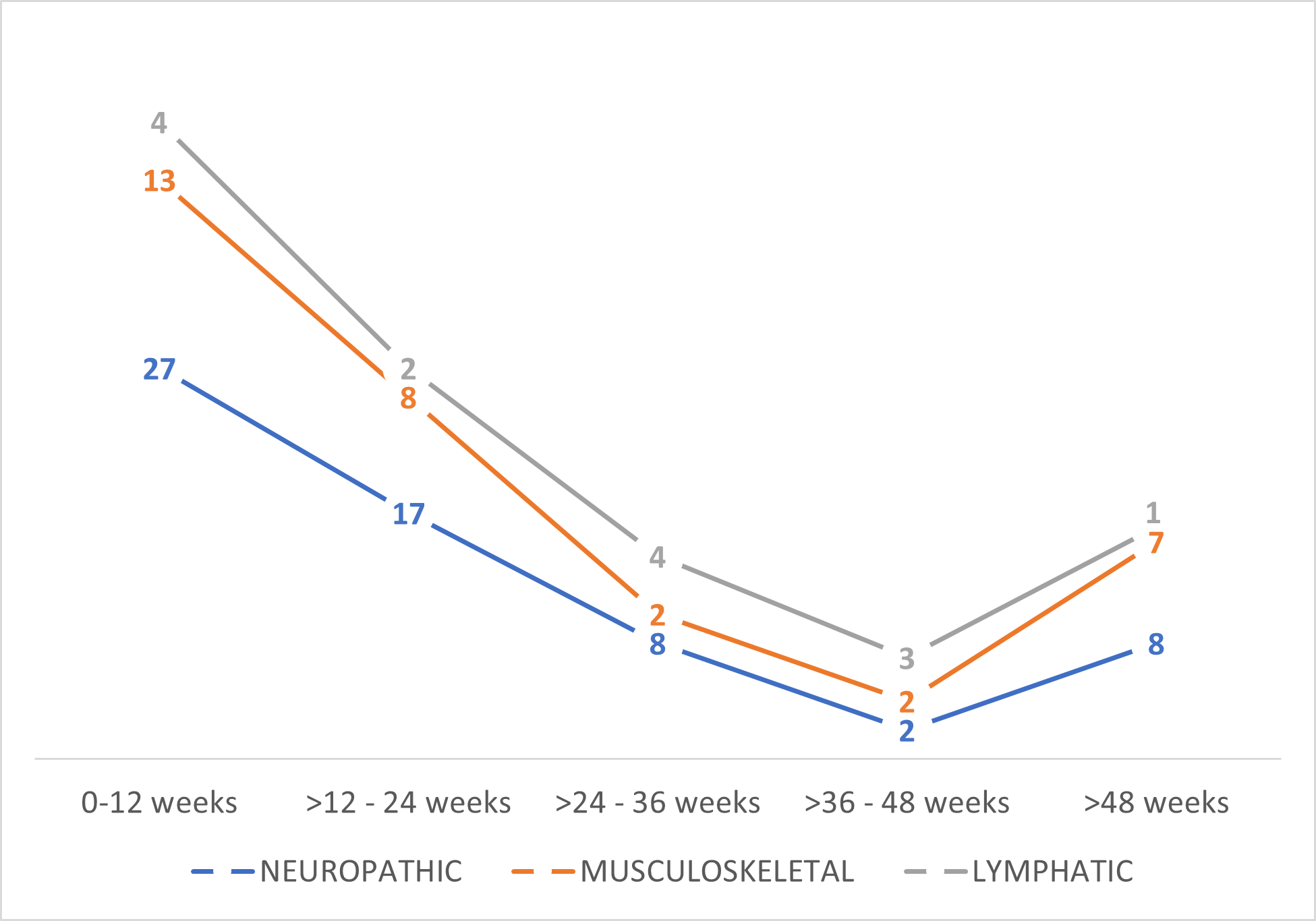

Pain and Disability assessment results: Among the causes of pain, 82 patients suffered neuropathic pain (64%), 32 patients showed musculoskeletal pain as principal origin (26%), and 14 patients (11%) suffered pain related with impairment in lymphatic drainage in mammary area or axillar web syndrome. Table 2 shows patients’ distribution according to principal causes of pain analyzed and Figure 1 shows how the different types of pain have developed over time.

|

Neuropathic pain |

Scar pain |

35 (37.5) |

|

Intercosthobrachialgia |

31 (24.2) |

|

|

Other brachialgies |

16 (12.5) |

|

|

Musculoskeletal pain |

Fibrosis |

20 (15.6) |

|

Glenohumeral joint pain |

12 (9.4%) |

|

|

Lymphatic drainage impairment |

Mammary lymphedema |

6 (4.7) |

|

AWS |

8 (6.3) |

Figure 1. Number of patients with different types of pain over time.

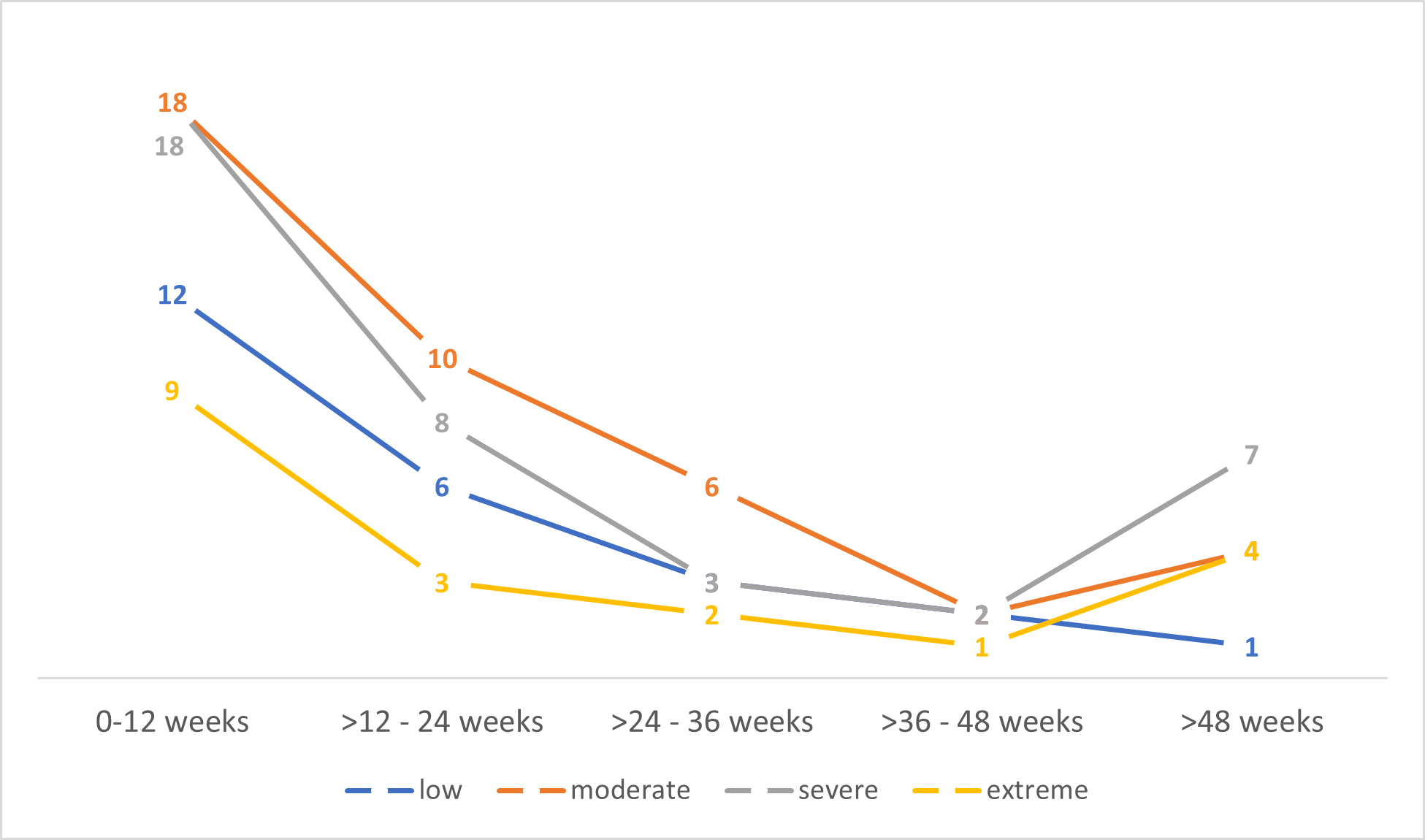

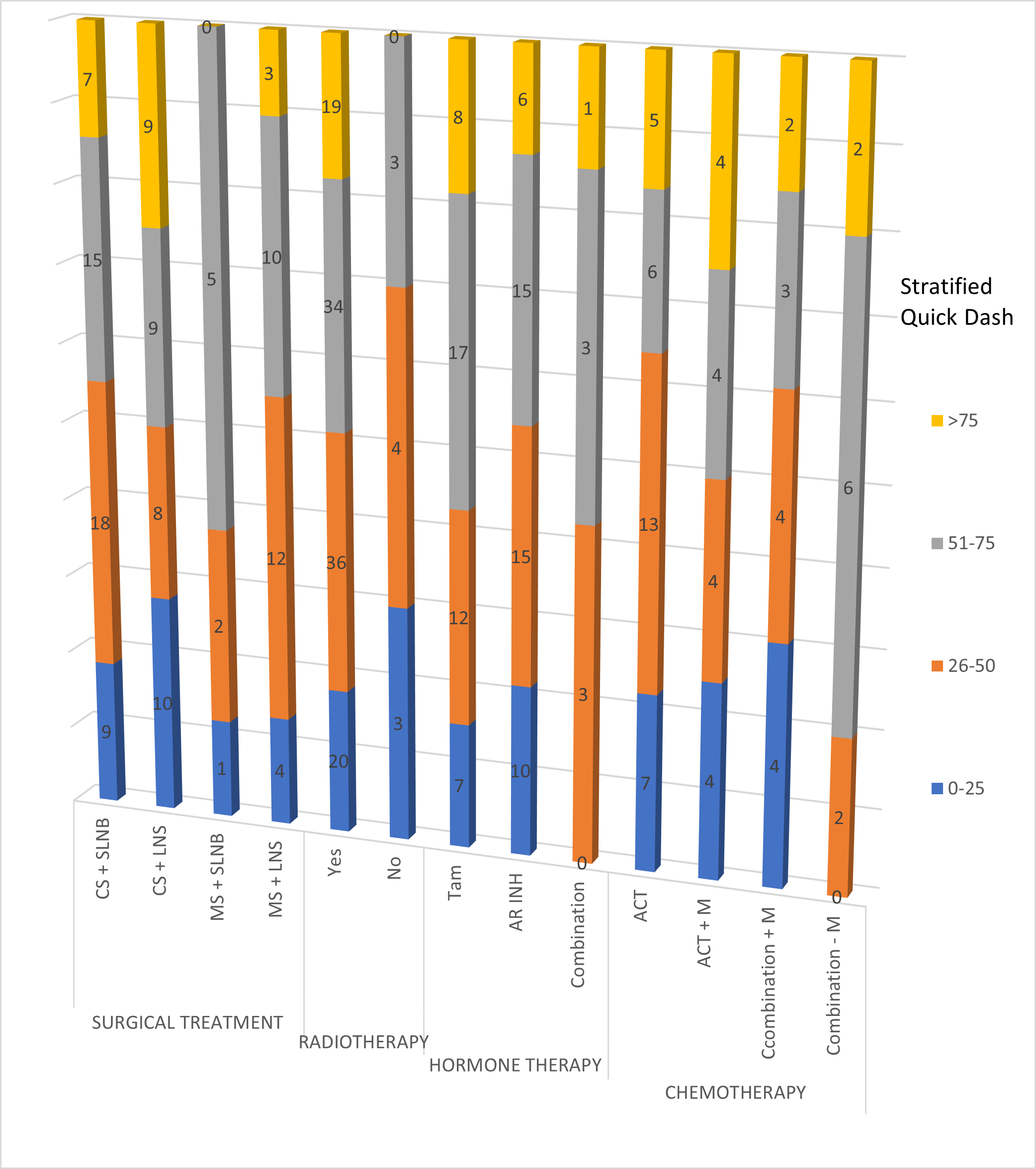

Regarding Quick Dash score, the mean value was 49.26 (4.54-100; SD:23.64). Figure 2 shows the distribution disability along time in function of delay between surgical treatment and clinical evaluation and Figure 3 shows the severity of disability stratified by type of treatment.

Figure 2. Stratified Quick Dash score by delay between surgery and clinical assessment and number of patients per period.

Figure 3. Severity of disability stratified by type of treatment (number of patients across columns for each level of stratified Quick Dash score). CS: Conservative Surgical; SLNB: Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy; LNS: Lymph Node Surgery; RT: Radiotehrapy; T: Tamoxifen; Ar Inh: Aromatase Inhibitors; A: Anthracyclines; C: Cyclophosphamide; T: Taxane; M: Monoclonal Antibodies

Statistical correlation results

Pearson correlation for quantitative variables with normal distribution shows that there is direct moderate correlation between BMI and Quick Dash: R=0.182; p value: 0.049, but there is no correlation between age and Quick Dash score: R= -0.019; p value: 0.834.

Non parametric Spearman correlation between quantitative variables without normal distribution, ordinal variables, and qualitative variables shows that there is no correlation between type of pain with the exercise habits (rs = 0,05), or with the type of chemotherapy (rs = -0.05), or hormone therapy (rs = -0.02). There is a low correlation between BMI, age, and pain (rs = 0,17 and 0,14, respectively). There is a low negative correlation between surgery (rs = -0.27) and radiotherapy (rs = -0.09) with pain experience. There is a moderate correlation between the time elapsed since surgery and our assessment (rs = 0.31).

In relation with perceived disability, there is no correlation with the sport habit (rs = 0.01), or with the type of surgery (rs = 0.01), or hormone therapy (rs = 0.04) or elapse time since surgery and our assessment (rs = 0.01). There was a very low correlation between chemotherapy and perceived disability (rs = 0.16) and there is a very low negative correlation between perceived disability and the application of radiotherapy (rs = -0.13).

The non-parametric correlation between pain and perceived disability shows low negative correlation (rs = -0.09).

Linear logistic regression: Results are shown in Table 3. Type of surgery and delay between surgery and medical visit are the risk factors associated with PMPS (p= 0.004 and 0.016 respectively). Regarding perceived disability, the risk factors for worst results are BMI (p= 0.034) and delay between surgery and medical assessment (p=0.024).

|

Dependent variable |

Independent variable |

R2 |

S.E. |

t |

p |

95% CI |

|

|

Lower |

Upper |

||||||

|

Pain |

Age |

0.02 |

1.69 |

1.72 |

0.088 |

0.00 |

0.04 |

|

BMI |

0.02 |

1.70 |

1.64 |

0.103 |

-0.01 |

0.10 |

|

|

Sport habit |

0.01 |

1.72 |

0.83 |

0.408 |

-0.23 |

0.57 |

|

|

Delay |

0.05 |

1.68 |

2.45 |

0.016* |

0.00 |

0.01 |

|

|

Surgery |

0.06 |

1.66 |

-2.94 |

0.004* |

-0.61 |

-0.12 |

|

|

Radiotherapy |

0.01 |

1.72 |

-1.08 |

0.282 |

-1.49 |

0.44 |

|

|

Hormone therapy |

0.00 |

1.71 |

-0.11 |

0.909 |

-0.41 |

0.36 |

|

|

Chemotherapy |

0.00 |

1.60 |

-0.24 |

0.811 |

-0.39 |

0.31 |

|

|

Quick Dash |

Age |

0.01 |

0.98 |

-1.08 |

0.283 |

-0.02 |

0.01 |

|

BMI |

0.04 |

0.96 |

2.14 |

0.034* |

0.00 |

0.07 |

|

|

Sport habit |

0.00 |

1.00 |

0.03 |

0.975 |

-0.24 |

0.24 |

|

|

Delay |

0.04 |

0.96 |

2.29 |

0.024* |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|

|

Surgery |

0.00 |

0.99 |

0.01 |

0.992 |

-0.15 |

0.15 |

|

|

Radiotherapy |

0.02 |

0.97 |

-1.48 |

0.141 |

-1.11 |

0.16 |

|

|

Hormone therapy |

0.00 |

0.96 |

0.17 |

0.866 |

-0.21 |

0.25 |

|

|

Chemotherapy |

0.03 |

1.02 |

1.40 |

0.165 |

-0.07 |

0.38 |

|

|

Pain |

Quick Dash |

0.01 |

1.71 |

-0.86 |

0.391 |

-0.02 |

0.01 |

|

|

Quick Dash cod |

0.01 |

1.71 |

-1.07 |

0.286 |

-0.48 |

0.14 |

|

Quick Dash |

Pain |

0.01 |

0.98 |

-1.07 |

0.286 |

-0.16 |

0.05 |

|

|

Pain cod |

0.01 |

0.98 |

-1.16 |

0.250 |

-0.40 |

0.11 |

Discussion

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines postmastectomy pain syndrome (PMPS) as persistent pain that appears shortly after mastectomy/lumpectomy, affecting the anterior chest, axilla and/or the upper and medial arm [8]. The variety of definitions used in the PMPS has resulted in a difference in methodology in clinical studies, i.e., inclusion/exclusion criteria and outcome measures. In the present study we have considered the existence of postmastectomy syndrome among those women referred to our unit with pain in the locations described, not present before the approach to the breast tumor, representing 23.06% of the total number of patients attended.

In general, the IASP establishes 3 months as the limit for considering a pain as chronic. In our case, the sample analyzed shows great variability from surgery to the medical visit in our unit; for this reason, we have decided to categorize the delay in periods of three months. This has allowed us to assess the proportion of patients with PMPS as a function of the time from surgery to the medical visit, and we have observed that there is a moderate correlation between elapse time since surgery and our assessment. The proportion of women with PMPS was higher in the first 3 months and tended to decrease over time, but after 1 year the number of women with PMPS increased (Figure 2). In fact, according to the literature, PMPS with moderate to severe pain affecting 15% to 60% of women at 1 year from surgery [1,2] which is associated with functional impairment and reduced quality of life [3]. Linear regression (Table 3) shows that delay between surgery and our assessment is a risk factor for feeling pain (p= 0.016) and disability (p= 0.024). This should alert us to the importance of early diagnosis and treatment to avoid prolonged pain.

There are many different causes of pain after breast cancer surgery. We have grouped them into 3 main groups (neuropathic, musculoskeletal, and lymphatic) for educational purposes to guide the appropriate treatment (which is not the subject of this paper), based on patients' description of pain and clinical examination, in order to analyze if there was relationship with the perceived disability. We found that there was a low negative correlation between Quick Dash score and the type of the pain (rs= -0.07).

In a recent prospective study carried by Chiang et al., it was found that neuropathic pain was associated with higher intensity pain after breast surgery [9]. In our sample neuropathic pain is the most common cause of pain in each categorized time period but we cannot confirm that this is a risk factor for worst disability based on linear regression. This may be because in clinical practice several types of pain overlap in the same patient and, in our study, we haven’t analyzed the pain grade.

Indeed, some socio-psychological variables as catastrophizing [10] have been account in women with persistent pain. We analyzed exercise habits because it is well known that exercise is beneficial in reducing upper limb pain and disability after breast surgery [11,12]. In contrast we have not found Spearman correlation (rs= 0.001). We think that the reason is we asked about previous sport habits and the higher number of women in our sample was evaluated recently after surgery, so they haven't begun fit habit. On the other hand, we did not find that fit habit of exercise is a variable for predicting or protecting against pain and disability after breast surgery when we did linear regression analysis (Table 3).

The etiology of PMPS is probably multifactorial and may involve peripheral as well as spinal and supraspinal structures. Smith et al., have observed that in patients with persistent breast pain, the latency of potentials is increased between 250-310 ms and enhanced P260 amplitude when compared with breast cancer treatment without persistent pain patients [13].

The most accepted pathophysiological explanation is an injury to the intercostobrachial nerve (ICBN) during surgery that may be aggravated by adjuvant treatment. The innervation of the breast depends on the intercostal nerves T2 to T6, and during surgery, the intercostobrachial nerve (T2) and the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm (C8-T1) can be damaged. Other contributors to the neuropathic pain following breast cancer surgery are damages to the medial and lateral pectoral, long thoracic, or thoracodorsal nerves, which are routinely spared but may be injured by scarring or by traction during mastectomy [14]. Our data support this hypothesis, as the highest proportion of pain reported by the patients was neuropathic in almost all the evolutionary moments in which we stratified the delay from surgery to our clinical examination.

Another specific causes of upper body pain and dysfunction in breast cancer survivors, include postsurgical pain by rotator cuff disease, adhesive capsulitis or arthralgias [15]. Shamley et al. [16] have shown higher limitations in glenohumeral range of movement and decreased muscle activity in four key muscles acting on the scapula in women with mastectomy than women with wide local excision. Edwards et al. [10] suggests that women who suffer breast painful display enhanced temporal summation of mechanical pain, deficits in endogenous pain inhibition that may be associated with alterations in central nervous system (CNS) pain-modulatory processes. Indeed, some inter-individual variability may reflect genetic variation that contributes to assessing abnormal responses to standardized noxious stimuli.

In our sample, pain in the shoulder region was the second most frequent cause of pain from surgery to 6 months and, like neuropathic pain, if left untreated, increases in prevalence after one year of evolution.

Another possible cause of pain and disability after breast cancer treatment is related to disturbances of the lymphatic drainage over the breast or axillary cord syndrome. Breast edema, unlike lymphoedema of the upper extremity, can be very painful and disabling. The surgery itself can cause damage to the lymphatic system, which can lead to a compromised transport capacity not only in the arm, but also in the breast. However, the main contributing factor is radiotherapy, which causes various tissue reactions, including edema [17]. Axillary web syndrome (AWS) refers to the development of fibrotic bands or “cords” in the axilla of patients who have undergone axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) for breast cancer [18]. Although AWS is non progressive and self-limited, generates painful disability in axillary zone and the upper limb affected [19]. These impairments have been the least cause of pain in our sample in each of the delay time categories.

Authors who have had prospective studies along the last 10 years agree that the risk factor for pain related with breast cancer surgery are: axillary lymph node dissection, preoperative pain, and severe acute postoperative pain at 1 week [1,9,22]. Younger age (<49 years) [9], and high BMI (>31 kg/m2) [1] are related too with PMPS [2,20]. There is no unanimous agreement regarding the relation with type of breast surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or endocrine therapy [1,2,21]. Chiang et al. [9] consider that oncological treatments (hormone therapy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgical treatment could influence on nociceptive pathway function and facilitate PMPS. In addition, this group has identified that women with COMT rs6269 GA genotype as risk factor for PMPS.

We cannot accurately compare our results with those published so far as the aim of our work has been to study the relationships between different types of postmastectomy pain and perceived disability. For this reason, we have opted for correlation statistics based on the retrospective data of our sample. Although the results of the non-parametric analysis do not determine the existence of correlations, we can affirm that the results are coherent with what has been accepted up to now, since BMI, age, surgery, and radiotherapy are the variables with the highest degree of correlation.

Our objective is to study if pain and disability are two faces of the same coin. It is logical thinking that intense pain is related with worst disability, but we did not find it.

This study has limitations. The first is due to the limitations of retrospective studies due to under-reporting of variables, as preoperative pain, phycological or genetic features, potentially relevant as predictors of pain and disability. Second, this is a single-center study carried out in a single teaching hospital. Third, our cohort of patients was quite small, so our results did not show a significant statistical correlation. Also, there is a large variability in delay time between surgery and our assessment; for these reasons we have considered that categorizing it might provide more reliable information.

Conclusions

Among women treated for breast cancer, pain characteristics are not related to the level of disability experienced. Neuropathic pain is the most common type.

Surgical techniques, radiotherapy, older age, and high BMI predispose to suffer pain derived from breast tumor treatment.

Women with post-mastectomy pain syndrome, elapse time since surgery and high BMI predispose to high levels of disability.

So, it is very important to prevent the onset of pain after breast tumor surgery to avoid long-term disability.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that exists with our institutions or financial matters.

References

2. Wang L, Guyatt GH, Kennedy SA, Romerosa B, Kwon HY, Kaushal A, et al. Predictors of persistent pain after breast cancer surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Cmaj. 2016 Oct 4;188(14):E352-61.

3. Hamood R, Hamood H, Merhasin I, Keinan-Boker L. Chronic pain and other symptoms among breast cancer survivors: prevalence, predictors, and effects on quality of life. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2018 Jan;167:157-69.

4. LeBlanc M, Stineman M, DeMichele A, Stricker C, Mao JJ. Validation of QuickDASH outcome measure in breast cancer survivors for upper extremity disability. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2014 Mar 1;95(3):493-8.

5. González GL, Sierra SF, Ricardo RM. Validación de la versión en español de la escala de función del miembro superior abreviada: Quick Dash. Revista Colombiana de Ortopedia y Traumatología. 2018 Dec 1;32(4):215-9.

6. https://www.gnu.org/software/pspp/

7. International Society of Lymphology. The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphedema. Consensus Document of the International Society of Lymphology. Lymphology. 2016;49:170-184.

8. Schug SA, Lavand'homme P, Barke A, Korwisi B, Rief W, Treede RD. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic postsurgical or posttraumatic pain. Pain. 2019 Jan 1;160(1):45-52.

9. Chiang DL, Rice DA, Helsby NA, Somogyi AA, Kluger MT. The incidence, impact, and risk factors for moderate to severe persistent pain after breast cancer surgery: a prospective cohort study. Pain Medicine. 2023 Sep 1;24(9):1023-34.

10. Edwards RR, Mensing G, Cahalan C, Greenbaum S, Narang S, Belfer I, et al. Alteration in pain modulation in women with persistent pain after lumpectomy: influence of catastrophizing. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2013 Jul 1;46(1):30-42.

11. Calapai M, Puzzo L, Bova G, Vecchio DA, Blandino R, Barbagallo A, et a;. Effects of Physical Exercise and Motor Activity on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Post-Mastectomy Pain Syndrome. Antioxidants. 2023 Mar 4;12(3):643.

12. Kannan P, Lam HY, Ma TK, Lo CN, Mui TY, Tang WY. Efficacy of physical therapy interventions on quality of life and upper quadrant pain severity in women with post-mastectomy pain syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Quality of Life Research. 2022 Apr;31(4):951-73.

13. Smith HS, Wu SX. Persistent pain after breast cancer treatment. Annals of Palliative Medicine. 2013 Jan;1(3):182-194.

14. Jung BF, Ahrendt GM, Oaklander AL, Dworkin RH. Neuropathic pain following breast cancer surgery: proposed classification and research update. Pain. 2003 Jul 1;104(1-2):1-13.

15. Stubblefield MD, Keole N. Upper body pain and functional disorders in patients with breast cancer. PM&R. 2014 Feb 1;6(2):170-83.

16. Shamley D, Srinaganathan R, Oskrochi R, Lascurain -Aguirrebeña I, Sugden E. Three-dimensional scapulothoracic motion following treatment for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2009 Nov;118:315-22.

17. Verbelen H, Tjalma W, Dombrecht D, Gebruers N. Breast edema, from diagnosis to treatment: state of the art. Archives of Physiotherapy. 2021 Dec;11:8.

18. Moskovitz AH, Anderson BO, Yeung RS, Byrd DR, Lawton TJ, Moe RE. Axillary web syndrome after axillary dissection. The American Journal of Surgery. 2001 May 1;181(5):434-9.

19. Dinas K, Kalder M, Zepiridis L, Mavromatidis G, Pratilas G. Axillary web syndrome: Incidence, pathogenesis, and management. Current Problems in Cancer. 2019 Dec 1;43(6):100470.

20. Mejdahl MK, Andersen KG, Gärtner R, Kroman N, Kehlet H. Persistent pain and sensory disturbances after treatment for breast cancer: six year nationwide follow-up study. Bmj. 2013 Apr 11;346:f1865.

21. Chrischilles EA, Riley D, Letuchy E, Koehler L, Neuner J, Jernigan C, et al. Upper extremity disability and quality of life after breast cancer treatment in the Greater Plains Collaborative clinical research network. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2019 Jun 30;175:675-89.