Abstract

Hemochromatosis is a medical condition marked by the accumulation of too much iron in the body's tissues and organs, which leads to eventual organ fibrosis and decreased function. The most common cause of primary iron overload is genetic hemochromatosis, whereas secondary iron overload is primarily caused by β-thalassemia major and sickle cell disease, which necessitates prolonged transfusion therapy and causes transfusional hemosiderosis. One of the primary organs for storing iron is the liver, which also displays iron excess first. The autosomal recessive condition beta thalassemia major (BT) is brought on by a markedly reduced production of healthy beta globin chains. Regular transfusions of red blood cells are the most common treatment for this condition because they reduce anemia and decrease inefficient erythropoiesis. Complications of iron over load are Hepatocellular carcinoma, heart issues, and endocrine issues, in addition to liver cirrhosis. In order to start treatment and avoid problems, it is crucial to detect and quantify liver iron overload, different methods are used, Ferritin measurements and the liver iron concentration (LIC) assay are the two main ways to evaluate iron loading. The current gold standard method for assessing organ-specific hemosiderosis is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a non-invasive technique used for the assessment of distribution, detection, grading, and monitoring of treatment response in iron overload. We discuss the possible use of MRI in determining hemochromatosis in thalassemia major patients which is the most significant condition with an iron overload.

Keywords

Secondary Hemochromatosis, Thalassemia major, Iron overload, Magnetic resonance imaging, Liver

Introduction

Hemochromatosis is a medical condition marked by the accumulation of too much iron in the body's tissues and organs, which leads to eventual organ fibrosis and decreased function [1]. Iron homeostasis in humans is solely dependent on iron intake regulation because iron excretion is passive (through shedding of intestinal and skin cells or in women, via menstruation) and cannot be actively unregulated [2].

Primary iron overload is most frequently linked to genetic hemochromatosis, while secondary iron overload is linked to inefficient erythropoiesis predominantly brought on by β-thalassemia major and sickle cell disease, which necessitates for an extended period transfusion therapy and results in transfusional hemosiderosis [3].

Patients with high iron absorption (hemochromatosis) or transfusion-dependent congenital or acquired anemia are more likely to develop iron overload [2].

Idiopathic hemochromatosis has a gene frequency of about 5%, a disease frequency of 0.3%, and a carrier frequency of 10% [1].

These patients' early hemochromatosis diagnoses enable for treatment to eliminate excess iron from the body and stop irreversible harm to tissues and organs [4]. Most of the time hemochromatosis radiological findings may be the first and only signs of the disease in these people, who may be clinically asymptomatic. As a result, radiologists ought to be highly suspect of this illness [1]. We discuss the possible use of MRI in determining hemochromatosis in thalassemia major patients which is the most significant condition with an iron overload.

Case Report

In this case, a 13-year-old girl known case of thalassemia major, presented to ER department with complain of generalized body weakness and paleness of skin for one month. She receives blood transfusions twice a week and had a splenectomy in the past; her family history was unremarkable. Patient was referred to radiology department for CT abdomen triphasic protocol, which showed findings of Hemochromatosis. After the diagnosis was made, iron chelation therapy was started to reduce the burden of iron built up from repeated transfusions. Chelating agents like deferoxamine, deferiprone, or deferasirox are commonly used, depending on factors such as iron levels, side effects, and patient preference. Treatment is guided by serial monitoring of serum ferritin and MRI-based liver iron concentration (LIC), which allow clinicians to adjust chelation intensity over time.

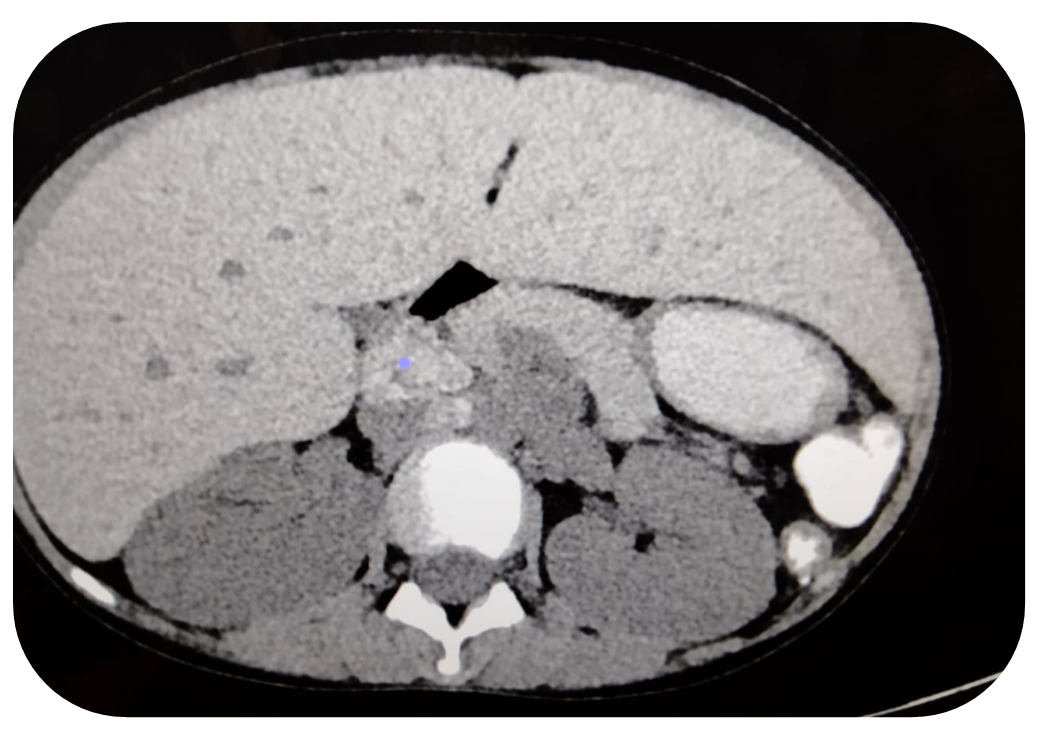

Figure 1. Shows enlarged hypodense liver with iron deposition.

Figure 2. Shows multiple enlarged hypodense areas at porta hepatis representing iron deposition nodes.

Figure 3. Shows iron deposition in liver and nodes representing hemochromatosis secondary to thalassemia.

Discussion

In humans, the regulation of iron levels primarily centers around managing the absorption of iron, since the elimination of iron occurs naturally through the shedding of cells in the intestines and skin. Additionally, women's iron excretion is further aided by the process of menstruation. Hemochromatosis is a pathological condition characterized by the excessive accumulation of iron in the parenchymal cells of various organs of body. This excessive iron buildup can result in the formation of fibrosis and impairing the normal functioning of the involved organs as time passes [1,2,5].

Hemochromatosis can be categorized into two forms: idiopathic (hereditary, primary, or genetic) and acquired. Idiopathic hemochromatosis is a condition inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, resulting from an abnormal gene closely linked to the A locus of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex on chromosome 6. Homozygous individuals with this gene usually experience severe iron overload and develop clinical symptoms of the disease. Heterozygotes, who carry one copy of the abnormal gene, exhibit increased iron absorption but typically do not develop iron overload or show clinical signs of the disease, unless a secondary cause is present [1,5–,7].

In contrast, acquired hemochromatosis occurs when iron overload develops as a consequence of another underlying disease or condition [7].

The primary cause of secondary hemochromatosis is excessive iron accumulation resulting from frequent blood transfusions. Each unit of packed red blood cells transfused contains approximately 200 to 250 mg of iron. This amount of iron is equivalent to the total normal intake of iron through the intestines over a period of approximately 6 months [6].

Hemochromatosis is commonly seen as a result of thalassemia (especially in the Mediterranean region) and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), which are the main underlying conditions [6].

Clinical symptoms of hemochromatosis typically manifest between the ages of 40 and 60 years. The liver is commonly the initial organ affected, with more than 95% of symptomatic patients experiencing hepatomegaly (enlarged liver). Liver cirrhosis, a late-stage complication, occurs in approximately 70% of symptomatic individuals. Among patients with liver cirrhosis, around 30% may develop hepatocellular carcinoma, a type of liver cancer [1].

It’s important to note that iron doesn't accumulate only in the liver—over time, excess iron can deposit in other organs like the heart and pancreas. Cardiac iron overload can lead to serious complications such as arrhythmias and heart failure, while pancreatic involvement can impair insulin secretion, increasing the risk for diabetes. However, these complications typically arise later in life, usually after years of chronic transfusions. In younger patients, such as our 13-year-old case, significant cardiac or pancreatic iron accumulation is uncommon. Therefore, a liver-focused MRI is generally sufficient at this stage [5,8].

Regular monitoring using MRI, tailored to assess iron in specific organs, plays a key role in guiding treatment. As highlighted in recent research by Meloni et al., tracking iron levels in the liver, heart, and pancreas over time helps adjust chelation therapy more precisely and can significantly improve patient outcomes [8].

Iron overload can lead to additional complications, including impaired glucose tolerance or the development of diabetes mellitus. It can also contribute to the occurrence of cardiac arrhythmias and heart failure [7]. Approximately 25–50% of patients with hemochromatosis experience the development of arthritis and arthralgia (joint pain). Initially, the small joints of the hands, particularly the second and third metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, are commonly affected [1].

Serum ferritin levels is a cost-effective screening test, it has limitations in terms of its specificity for iron overload. Elevated serum ferritin levels can be observed in conditions other than iron overload, including inflammation. Therefore, for a suspected diagnosis of secondary hemochromatosis, additional diagnostic measures are necessary to confirm the presence of iron accumulation.

Imaging techniques such as MRI or computed tomography (CT) scans can provide valuable information about the distribution and extent of iron accumulation in the liver and other organs. These imaging modalities can help visualize iron deposition patterns and assess the severity of iron overload. They are particularly useful because liver biopsy, which was previously considered the gold standard for diagnosing iron overload, may not accurately reflect the heterogeneous distribution of iron in the liver [6].

Therefore, when there is a suspicion of secondary hemochromatosis, imaging studies, such as MRI or CT scans, are important to confirm the presence and extent of iron accumulation [2,6]. These non-invasive techniques can provide a more comprehensive assessment of iron overload throughout the body, aiding in accurate diagnosis and treatment planning [1,9].

MRI plays a crucial role in determining hepatic iron concentration (LIC) in various diseases characterized by iron overload. In the presence of iron overload in the liver, MRI can detect the accumulation of iron due to the paramagnetic effects of iron. The liver in hemochromatosis typically shows marked decreased signal intensity on T2-weighted spin-echo images and moderately decreased signal intensity on T1-weighted spin-echo images. The ratio of the signal intensity in T2-weighted images of the liver to that of the paraspinous muscle, with a critical value of less than 0.5, is a calculated parameter that has been found to be the best predictor for the degree of hepatic iron overload [1,2]. This parameter helps assess the severity of iron accumulation in the liver.

However, it is important to consider the differential diagnosis when encountering generalized hepatic hypointensity on T1- and T2-weighted images. Apart from iron overload, other conditions that can cause similar imaging findings include:

1. Wilson's Disease: Wilson's disease is a genetic disorder characterized by impaired hepatic copper transport, leading to copper accumulation. In advanced cases, it can cause hepatic hypointensity on T1-weighted and T2-weighted MRI images due to copper deposition.

2. Osler-Weber-Rendu Disease (Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia): This is a genetic disorder that affects blood vessels, leading to telangiectasias (abnormally dilated blood vessels). In some cases, hepatic involvement can result in hepatic hypointensity on MRI due to vascular changes.

In cases of generalized hepatic hypointensity on MRI, a comprehensive evaluation including clinical history, laboratory tests, and additional imaging studies may be required to differentiate between these various causes and establish an accurate diagnosis [1].

By accurately determining LIC through MRI, healthcare providers can assess the severity of iron overload, guide appropriate chelation therapy, monitor treatment effectiveness, and prevent complications associated with excessive iron accumulation [2]. It's important to note that while MRI is a valuable tool for LIC determination, clinical judgment and consideration of other diagnostic factors are necessary for comprehensive management of patients with iron overload disorders [2].

The therapy for hemochromatosis aims to address the excess accumulation of iron in the body and provide supportive treatment for any organ damage that may have occurred. The primary method of removing excess iron is through regular phlebotomy, which involves the withdrawal of blood.

In hemochromatosis, weekly or twice-weekly phlebotomies of 500 ml (approximately one pint) of blood are often recommended. This regular blood removal helps reduce iron levels in the body by depleting the iron stores. By removing blood containing excess iron, phlebotomy can restore iron balance and prevent further iron-related damage to organs [1].

Supportive treatment of damaged organs is also an essential component of hemochromatosis management. If organ damage has occurred due to iron overload, specific interventions may be necessary to address those complications. For example, if the liver is affected, treatment may focus on managing liver disease, such as through medications, lifestyle changes, or other interventions aimed at preserving liver function [1].

It is important for individuals with hemochromatosis to work closely with their healthcare providers to develop a personalized treatment plan that considers their specific needs and circumstances. Regular monitoring of iron levels, organ function, and overall health is crucial to ensure effective management and prevention of complications associated with hemochromatosis.

Conclusion

In the course of thalassemia major, hemochromatosis frequently develops and necessitates long-term transfusion therapy, which causes transfusional hemosiderosis. It is vital to constantly monitor patients even if clinically asymptomatic in order to prevent potential problems from chronic iron overload. These patients may even show up on imaging tests before their condition has advanced. Therefore, radiologists should get more involved in the identification of hemochromatosis patients. The gold standard method for assessing organ-specific hemosiderosis is MRI, a non-invasive technology used for analyzing, distribution, recognition, grading, and tracking response to therapy in high iron levels.

References

2. Tziomalos K, Perifanis V. Liver iron content determination by magnetic resonance imaging. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Apr 7;16(13):1587–97.

3. Labranche R, Gilbert G, Cerny M, Vu KN, Soulières D, Olivié D, et al. Liver Iron Quantification with MR Imaging: A Primer for Radiologists. Radiographics. 2018 Mar-Apr;38(2):392–412.

4. Rose C, Vandevenne P, Bourgeois E, Cambier N, Ernst O. Liver iron content assessment by routine and simple magnetic resonance imaging procedure in highly transfused patients. Eur J Haematol. 2006 Aug;77(2):145–9.

5. Bassett ML, Halliday JW, Powell LW. Genetic hemochromatosis. Semin Liver Dis. 1984 Aug;4(3):217–27.

6. Gattermann N. The treatment of secondary hemochromatosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009 Jul;106(30):499–504.

7. Castiella A, Zapata E, Alústiza JM. Non-invasive methods for liver fibrosis prediction in hemochromatosis: One step beyond. World J Hepatol. 2010 Jul 27;2(7):251–5.

8. Meloni A, Positano V, Ricchi P, Pepe A, Cau R. What is the importance of monitoring iron levels in different organs over time with magnetic resonance imaging in transfusion-dependent thalassemia patients? Expert Rev Hematol. 2025 Apr;18(4):291–9.

9. Soltanpour MS, Davari K. The Correlation of Cardiac and Hepatic Hemosiderosis as Measured by T2*MRI Technique with Ferritin Levels and Hemochromatosis Gene Mutations in Iranian Patients with Beta Thalassemia Major. Oman Med J. 2018 Jan;33(1):48–54.