Commentary

Nowadays, there are two heart valve prosthesis types available: mechanical or biological. Apart from the long-term durability of mechanical heart valves, there are considerable advantages of bioprothesis, specifically regarding biocompatibility and the abdication of oral anticoagulation by warfarin, with the respective drawbacks and risks. A practical proof of this is that is estimated in the United States, between 2007 and 2011, 63.6% of prosthetic valve devices were made of bovine pericardium (an increase of 100% compared to the period from 1998 to 2001) [1,2]. An important factor that justifies this data is the average age of patients with valvopathy: usually older, in which warfarin anticoagulation can imply considerable bleeding risk. Since 2002, when Cribier described the first transcatheter valve implantation in the aortic position in a human [3], there was widespread use of transcatheter valves not only for the treatment of aortic valve stenosis, but also for the treatment of degenerated conventional bioprothesis has started (known as "valve-in-valve"), which the first in human implantation was performed by Wenaweser in 2007 [4]. Moreover, it comes from 2016 the first report of sequential valve-in-valve implantation in a degenerated transcatheter valve previously implanted in a bioprothesis, by Leung et al. [5].

However, either conventional bioprothesis or transcatheter valves have limited durability (due to the heterologous tissue used in the construction of the prosthetic valves leaflets). Transcatheter therapy is an alternative for reoperation for degenerated conventional bioprothesis. Moreover, there are two determinants that arises the valve-in-valve and sequential valve-in-valve: the improvement in health care, that leads to a progressive aging of the population, with possible dysfunction of bioprothesis, and potentially higher operative risk [6]; and the trials, with emphasis on the Evolut Low Risk Trial and Partner 3 Trial [7,8], with current studies regarding intermediate-risk and low-risk patients for transcatheter aortic valve implantation, and consequently younger patients.

The in vitro research on valve-in-valve and sequential valve-in-valve with a Brazilian transcatheter valve and Brazilian bioprothesis [9] provide valuable insights for the clinical application of the valve-in-valve procedure, considering the different combinations of bioprothesis sizes and transcatheter valves and allows a great reflection about election of valve types.

As the durability of transcatheter valve resembles conventional bioprothesis, it is possible to figure out that a patient can have sequential valve-in-valve implants throughout life. Nevertheless, patient-prosthesis-mismatch (PPM) plays an important role, especially in valve-in-vale aortic position. PPM is defined as an insufficient effective orifice area of the inserted prosthetic valve in relation to the body surface area of the patient.

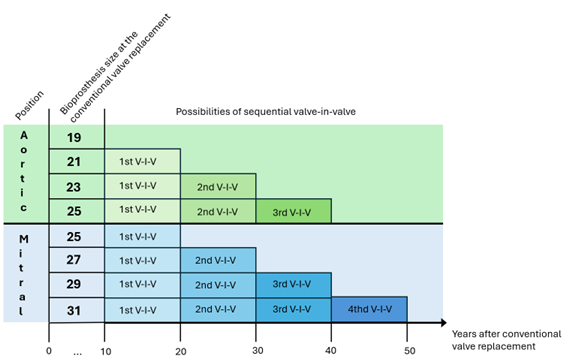

For instance: according to the study mentioned, a patient with a 23 mm size aortic Braile conventional bioprothesis can safely have a 22mm size Inovare transcatheter implanted, and a subsequent implant of a 20 mm size Inovare with borderline outcomes. Considering an hypothetical patient submitted at the age of 55 to a conventional aortic valve replacement with a 23 mm size Braile bioprothesis, is expected between 65 and 70 years of age the degeneration of that bioprothesis, when a valve-in-valve procedure with a 22 mm size Inovare can be performed; and in the future, by the age of 75-80 years of age, a sequential valve-in-valve can be performed, with a 20 mm size Inovare, that might last until 85-90 years of age (above average life expectancy throughout the world). For the mitral position, PPM usually has less impact, since in most cases the size of the implanted conventional bioprosthesis is considerably greater for the risk of mismatch; the aforementioned study even reveals that it is possible, in a sequential mitral valve-in-valve, to proceed with the implantation up to a 24 mm transcatheter valve. As an example, a 29 mm size conventional bioprothesis can receive three sequential transcatheter implantation up to 24 mm size; that might mean at least 40 years free of bioprothesis dysfunction.

With these examples, apart from patient’s desire and other contraindications, the choice between biological or mechanical valve cannot be based only on age but should as well in valve size by the time of the first conventional implant. For instance, in a conventional aortic valve replacement, the suitable prosthesis size is 25 mm: considering the sequential valve-in-valve (and considering three possible transcatheter therapy), there might be a tendency for electing a bioprothesis? On the other side, in another conventional aortic valve replacement, the suitable prosthesis size is 21 mm (that fits to the body surface area): considering just one possible future transcatheter therapy, would the choice be for mechanical valve?

After all these thoughts, the following graphic represents the possible free of bioprothesis dysfunction time considering the feasibility of sequential valve-in-valve and estimating the durability of ten years for bioprothesis. Obviously, this graphic reflects the result of the study mentioned, and there may be different results between bioprothesis and transcatheter valves from different manufacturing companies regarding the number of possible valve-in-valve procedures.

The consolidation of valve-in-valve and sequential valve-in-valve might adjust this guidelines’ paradigm when it comes to age and the choice of heart valve prosthesis.

Conventional reoperation for degenerated bioprothesis is a very significant factor to be considered when choosing the type of valve prosthesis, since it can add up to 8% at operative risk [10]. In this context, valve-in-valve is an excellent alternative to reoperation; it can also be considered when choosing the type of cardiac valve prosthesis.

As the size at the first conventional implantation might be considered in the choice of the heart valve prosthesis, there comes an important observation, especially in aortic valve replacement: is it valid to systematically proceed the aortic root enlargement (even in the procedure the size of the bioprothesis is suitable), aiming a bigger bioprothesis and validate a future sequential valve-in-valve?

The current and classic techniques of aortic root enlargement applied in adult cardiac surgeries are the Nicks and Manouguian procedures [11,12]. The Nicks procedure generally enhances one valve size bigger; the Manouguian demands incising the mitral valve anterior leaflet and left atrium, with risk of mitral regurgitation. Both procedures result in longer cardiopulmonary time and aortic cross-clamp time, enhancing operative risks. At this point, it is not seen as an attractive routine procedure considering future demand. It is almost a consensus among cardiac surgeons that at the moment of surgical implantation of a conventional bioprothesis, the largest possible valve must be implanted, considering the surgical anatomy of the patient. Therefore, and with emphasis on the aortic position, a more invasive and higher risk surgery should be reserved for cases of strict necessity.

Graphic 1. The estimated time for bioprothesis dysfunction and the possibilities, according to the bioprothesis size, of valve-in-valve (considering an average of ten-year durability). V-I-V: valve-in-valve.

Another alternative for small aortic annulus relies in sutureless valves, and even in transcatheter valves, that have bigger effective orifice area in comparison to conventional bioprothesis.

At this point, considering the expansion of transcatheter therapy, in the near future the implantation of mechanical heart valve prosthesis can decrease even more. On the other hand, a recent cohort study concluded that mechanical mitral valves were associated with lower mortality than biologic valves among patients up to 70 years of age, whereas the benefit of a mechanical aortic valve disappeared by 55 years of age [13]. Albiet, this study did not take into consideration the transcatheter procedure for degenerated bioprothesis. This debate comes to an oblivious conclusion: there is no perfect cardiac valve prosthesis. Management of oral anticoagulation with warfarin is a key point for patients with mechanical heart valve prosthesis and demands regular medical follow-up. INR self-testing is a great tool to reduce either thrombotic or hemorrhagic complications; yet, in least developed and developing countries, self-testing has not been popularized. When it comes to biological heart valve prosthesis, the biggest drawback is durability; notwithstanding, the transcatheter therapy leads to a less invasive alternative to manage bioprothesis degeneration.

The most important message, regardless of the surgeon's preference for mechanical or biological heart valve prosthesis, there are tools to address the imperfections of each type of prosthesis. And due to the expansion of the use of bioprothesis, valve-in-valve is an excellent therapy, less invasive, with progressive studies validating its feasibility.

References

2. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, Milojevic M, Baldus S, Bauersachs J, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease: Developed by the Task Force for the management of valvular heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). European heart journal. 2022 Feb 14;43(7):561-632.

3. Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Bash A, Borenstein N, Tron C, Bauer F et al. Percutaneous transcatheter implantation of an aortic valve prosthesis for calcific aortic stenosis: first human case description. Circulation 2002; 106(24):3006-8.

4. Wenaweser P, Buellesfeld L, Gerckens U, Grube E. Percutaneous aortic valve replacement for severe aortic regurgitation in degenerated bioprosthesis: the first valve in valve procedure using the Corevalve Revalving system. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 2007 Nov 1;70(5):760-4.

5. Sang SL, Giri J, Vallabhajosyula P. Transfemoral transcatheter valve-in-valve-in-valve replacement. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2016 Aug 1;152(2):622-3.

6. Kostyunin AE, Yuzhalin AE, Rezvova MA, Ovcharenko EA, Glushkova TV, Kutikhin AG. Degeneration of bioprosthetic heart valves: update 2020. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2020 Oct 6;9(19):e018506.

7. Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, Mumtaz M, Gada H, O’Hair D, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding valve in low-risk patients. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019 May 2;380(18):1706-15.

8. Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, Makkar R, Kodali SK, Russo M, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a balloon-expandable valve in low-risk patients. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019 May 2;380(18):1695-705.

9. Cardoso CC, Gaia DF, Palma JH, Oliveira Jr JL. The End of Repeated Reoperations for Degenerated Bioprosthesis? Hydrodynamic In-Vitro Analysis for Sequential Valve-in-Valve Feasibility. J Clin Exp Cardiolog. 2024;15:912.

10. Huygens SA, Mokhles MM, Hanif M, Bekkers JA, Bogers AJ, Rutten-van Mölken MP, et al. Contemporary outcomes after surgical aortic valve replacement with bioprostheses and allografts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2016 Oct 1;50(4):605-16.

11. Nicks R, Cartmill T, Bernstein L. Hypoplasia of the aortic root: the problem of aortic valve replacement. Thorax. 1970 May 1;25(3):339-46.

12. Manouguian S, Seybold-Epting W. Patch enlargement of the aortic valve ring by extending the aortic incision into the anterior mitral leaflet: new operative technique. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1979 Sep 1;78(3):402-12.

13. Goldstone AB, Chiu P, Baiocchi M, Lingala B, Patrick WL, Fischbein MP, et al. Mechanical or biologic prostheses for aortic-valve and mitral-valve replacement. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017 Nov 9;377(19):1847-57.