Commentary

The term “tandem spinal stenosis (TSS)” has been used to describe combined cervical and lumbar canal stenosis. We identified in our large series of cases that approximately 58% of cases with cervical canal stenosis were considered to be TSS, and 15% needed surgery for concurrent lumbar spinal canal stenosis (LCS) [1]. The simultaneous presence of thoracic canal stenosis and LCS is also frequently observed at a clinical site. As was discussed in the previous article, “Surgical outcomes of the thoracic ossification of ligamentum flavum: a retrospective analysis of 61 cases”, primary thoracic spinal stenosis is rare, and the thoracic ossification of ligamentum flavum (T-OLF) coincides with spinal spondylosis deformans, leading to a high incidence of tandem T-OLF and other stenosis lesions in the cervical (38%) or lumbar area (75%), sometimes with the ossification of ligaments [2]. The author outlined the clinical and radiological features of T-OLF, especially focusing on this high incidence of combined spinal stenosis, and comparing the clinical outcomes among surgical methods in the present article. Statistical analysis was performed using the Student’s unpaired t test, the Mann-Whitney U test, and 1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey-Kramer’s post hoc test. All data are expressed as the means ± standard deviation (SD). A p value less than 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

When an OLF patient has severe myelopathy, concurrent LCS is often obscured by symptoms caused by a thoracic lesion, leading to difficulty in identifying the origin of these neurological findings, despite improved diagnostic tools such as whole spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Computed tomography (CT) after myelography offers great advantages for visualizing bony lesions, such as OLF, ossification of the longitudinal ligament (OPLL) and diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH). Therefore, we have used CT myelography (CTM) not only to gain an insight for the prevalence, distribution, and morphology of T-OLF, but also to evaluate the cervical and/or lumbar lesions. Cases with the ossification of ligaments have a tendency to develop into TSS at a relatively younger age when compared with spondyltic cases [1]. Interestingly, although up to 75% of thoracic myelopathy patients who underwent T-OLF surgeries had LCS, whole spine CTM revealed that spondylotic process was mainly observed in the lower lumbar spine of these T-OLF patients, and the incidence of lumbar ossified lesions was quite low (8%) [2]. It is important to keep in mind that there are differences in the distribution of stenotic lesions between OPLL/OLF and spondylotic cases [3, 4].

Despite such a high incidence of combined spinal stenosis, there is no consensus on the optimal surgical approach for this T-OLF condition. We conducted a survey of 61 myelopathic patients with T-OLF according to univariate analyses of surgical outcomes. An advanced age, a short stature, and the presence of concurrent lumbar stenosis were associated with poor outcomes (recovery rate for the T-JOA [the Japanese Orthopaedic Association for thoracic myelopathy] score < 40%) after surgery. The duration of disease, preoperative manual muscle test (MMT) grade, complication rate, size, configuration, severity of the involved T-OLF, and even the presence of intramedullary high-intensity area were not statistically associated with poor outcomes. Of note, the good outcome group included a larger number of patients with cervical stenosis including OPLL (8/31 cases vs 15/30 cases, p=0.0524). Moreover, this group tended to have more wide-ranging OLFs, and included a large number of cases treated with upper thoracic decompression surgery than did the poor outcome group. Apart from spinal cord compression, there were 21 patients with single level OLF and 40 patients with multi-segmental OLFs (an average of 3.1 intervertebral levels, range 2-12 levels) in thoracolumbar spine. On the other hand, compressive OLFs involved with myeloradiculopathy were located at single-level in 42 patients, two-levels in 11 patients, and more than three-levels in 8 patients (an average of 1.5 intervertebral levels, range 1-4 levels). Based on their predilection in the lower thoracic spine (Th9-Th12), the dynamic biomechanical factor could be strongly attributed to the poor outcome in T-OLF cases, rather than their sizes, configurations, or number of affected lesions. Goel et al. identified that vertical spinal instability manifested by facetal overriding or telescoping is the nodal point of pathogenesis of TSS [5]. Standing human position, aging muscles, and sedentary life style may have a contributory effect on the pathogenesis of entire spectrum of spondylosis or degeneration of the spine, including T-OLF. Although global spinal alignment was not statistically associated with poor outcomes in T-OLF, the tandem T-OLF and LCS group significantly included a greater number of elderly patients with Modic change in thoracic spine and a greater sagittal vertical axis, resulting in the lower neurological recovery in the study [2]. Biomechanical evaluations in the thoracic lesion, which have a limited range of segmental motion, and the elastic lumbar spine need to be collected in the future to study the clinical outcomes of T-OLF.

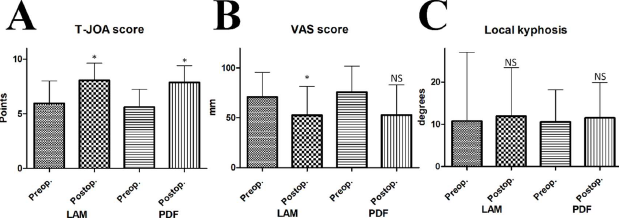

As for the surgical procedure, laminectomy with or without instrumentation was limited to these compressed spina cord levels. Thereupon, we retrospectively compared surgical outcomes between the laminectomy group (LAM, n=44) and the posterior decompression with fusion group (PDF, n=17). There were no significant differences in terms of middle-term clinical outcomes including perioperative complication rate, and postoperative local kyphotic change in alignment (recovery rate for the T-JOA score; 38.0 ± 29.0% vs 42.3 ± 30.5%, p=0.6341, ΔVAS score [visual analogue scale score for pain or numbness severity from chest to the toes]; 22.9 ± 32.3 mm vs 26.7 ± 37.7 mm, p=0.7260, complication rate; 15.9% vs 5.9%, p=0.3062, and Δlocal kyphosis; 2.4 ± 3.4 degrees vs 0.9 ± 1.8 degrees, p=0.00902, respectively) (Figure 1). The PDF group showed a lower preoperative lumbar lordosis than the LAM group (40.3 ± 14.4 degrees vs 31.6 ± 15.8 degrees, p=0.0435), probably due to the selection bias. As expected, PDF was proved more invasive than LAM alone (operation time; 129.7 ± 77.0 min vs 226.8 ± 112.1 min, p=0.0003, blood loss; 205.1 ± 356.1 mL vs 491.2 ± 988.5 mL, p=0.0990). PDF may be appropriate for patients with severe T-OLF and preoperative myelopathy [6].

Figure 1: Comparison between the OLF cases treated by the thoracic laminectomy (LAM) and the cases treated by the posterior decompression with fusion (PDF). There were no significant differences between the LAM group and the PDF group in terms of (A) T-JOA score, (B) VAS score, and (C) local kyphostic change. *p<0.05 when compared to the preoperative status. NS: not significant.

Our surveys have demonstrated that the prognosis for combined stenosis patients with myelopathy was worse than for patients with isolated cervical/thoracic lesions [1,2]. In the operative sequence for combined spinal stenosis, the most clinically symptomatic area should be decompressed first. If neurological symptoms originate equally from both the cervical/thoracic lesions and LCS with severe radiological findings, both lesions require surgical decompression. Both the severity of lumbar lesions and age can have a critical impact on neurological improvement after cervical/thoracic surgery [1,2,7], and an additional surgery for another lumbar lesion could significantly improve the neurological outcomes. In cases without severe systemic problems, simultaneous cervical/thoracic and lumbar decompression is sometimes performed. Surgical algorithm for combined spinal stenosis should be tailored to the patient’s age and general condition, whether the procedures are performed simultaneously or in stages. As mentioned above, mechanical stress could influence the development of T-OLF, which is usually located in the lower thoracic spine. With or without fusion, any surgical procedure for T-OLF is acceptable as long as the mechanical compression and selective damage to the spinal cord are resolved. In the treatment of T-OLF, we should check the existence of combined stenosis, and examine a correlation between the clinical outcomes and the affected levels, taking notice of the elasticity of not only thoracic spine but also cervical/lumbar spine, to disclose OLF epidemiology and pathology.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

2. Yamada T, Shindo S, Yoshii T, Ushio S, Kusano K, Miyake N, et al. Surgical outcomes of the thoracic ossification of ligamentum flavum: a retrospective analysis of 61 cases. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2021 Jan 4;22(1):7.

3. Hirai T, Yoshii T, Iwanami A, Takeuchi K, Mori K, Yamada T, et al. Prevalence and Distribution of Ossified Lesions in the Whole Spine of Patients with Cervical Ossification of the Posterior Longitudinal Ligament A Multicenter Study (JOSL CT study). PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0160117.

4. Yamada T, Yoshii T, Yamamoto N, Hirai T, Inose H, Okawa A. Surgical outcomes for lumbar spinal canal stenosis with coexisting cervical stenosis (tandem spinal stenosis): a retrospective analysis of 565 cases. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 2018 Mar 20;13(1):60.

5. Goel A, Vutha R, Shah A, Rai S, Patil A. Is cervical instability the cause of lumbar canal stenosis? J Craniovertebr Junction Spine. 2019 Jan-Mar;10(1):19-23.

6. Ando K, Imagama S, Ito Z, Hirano K, Muramoto A, Kato F, et al. Predictive factors for a poor surgical outcome with thoracic ossification of the ligamentum flavum by multivariate analysis: a multicenter study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013 May 20;38(12):E748-54.

7. Eskander MS, Aubin ME, Drew JM, Eskander JP, Balsis SM, Eck J, et al. Is there a difference between simultaneous or staged decompressions for combined cervical and lumbar stenosis? Journal of Spinal Disorders & Techniques. 2011 Aug;24(6):409-413.