Abstract

Activating innate immune signaling in tumor cells to enhance anti-tumor immunity and increase T cell-mediated killing is the core objective of tumor immunotherapy. PRMT1, one of the most crucial PRMTs, plays a critical role in tumor progression and innate immunity. Recent research revealed that PRMT1 can inhibit the enzymatic activity of cGAS in part through PRMT1-mediated Arg methylation, thereby suppressing the anti-tumor immune response of cells. As such, inhibiting or knocking down PRMT1 can synergistically enhance the efficacy of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy by activating the cGAS-STING signaling pathway. Here, we provide a comprehensive description of the two key signaling components, PRMT1 and cGAS, in the PRMT1-cGAS-STING signaling pathway for therapeutic intervention to augment anti-tumor immunity. By understanding the specific physiological functions and regulatory mechanisms of PRMT1, as well as the extensive post-translational modifications (PTMs) of cGAS, we have identified several compounds and drugs that can directly target PRMT1 or cGAS, and/or indirectly target PRMT1 upstream regulators or cGAS-post-translational modifying enzymes as potential means to activate the cGAS-STING signaling pathway. However, further investigation is needed on the efficacy of combining this pathway activation with anti-PD1 therapy. This review suggests that targeting the PRMT1-cGAS-STING pathway with immune checkpoint inhibitors is likely a promising approach in tumor immunotherapy.

Protein Arginine Methylation and PRMTs

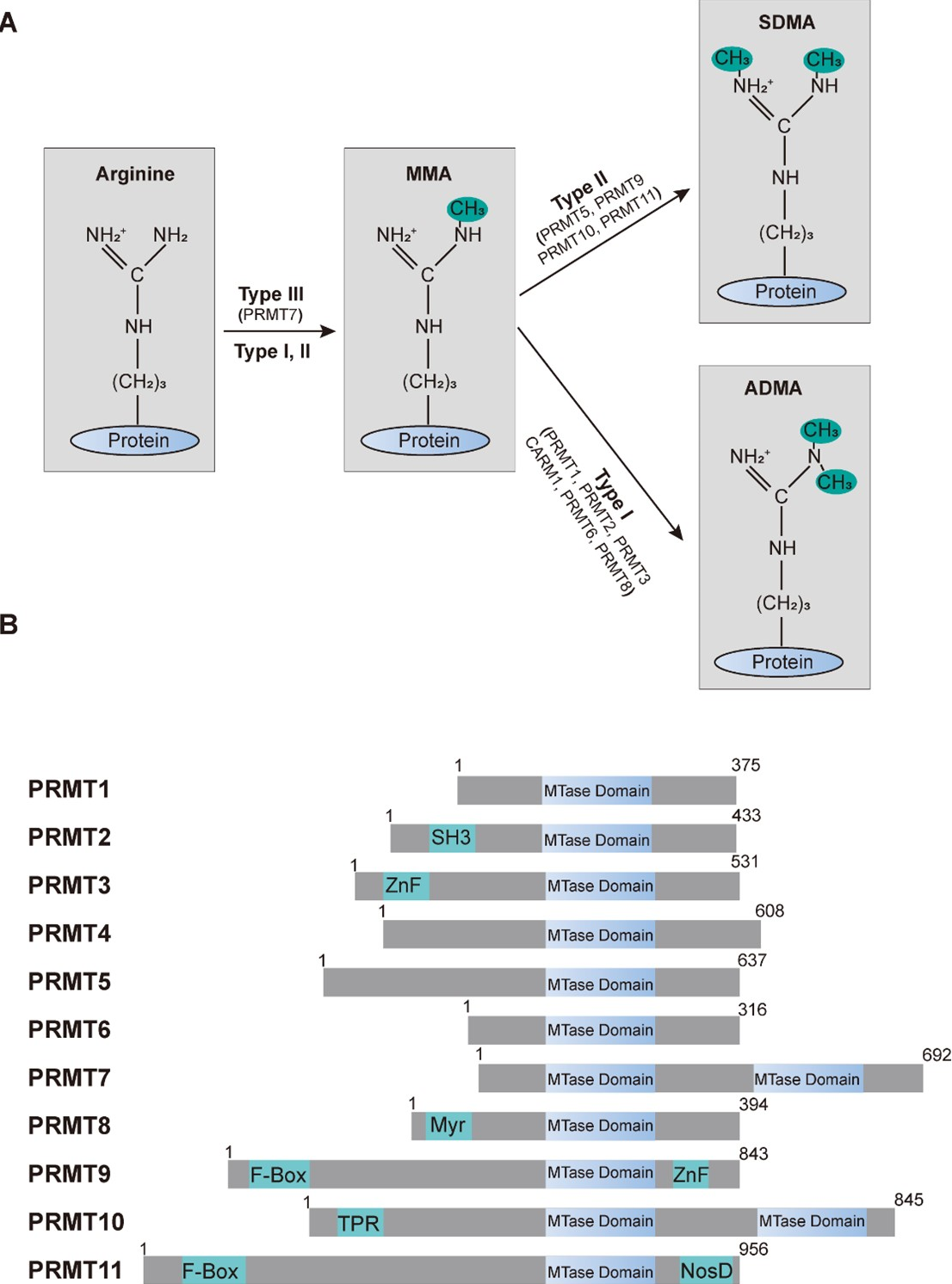

Post-translational modifications of proteins alter their biophysical properties, affecting stability, localization, and interactions, which are essential for proteome diversity and cellular homeostasis [1,2]. Protein arginine methylation is a post-translational modification where methyl groups are added to the arginine residues of substrate proteins [3,4], typically catalyzed by protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) [5]. This modification can occur as mono-methylation (MMA), asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), or symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) [6,7] (Figure 1). Arginine methylation affects protein function, interactions, and localization, which is crucial in regulating gene expression, signal transduction, RNA processing, and DNA repair [5]. This modification is essential for cellular homeostasis and various biological processes.

Figure 1. Protein arginine methylation and the family of PRMTs. (A) Arginine methyltransferases and their impact on protein arginine methylation patterns. The arginine residue possesses five potential hydrogen bond donors. In mammals, PRMTs utilize the methyl group from S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) to create mono-methylarginine (MMA). Subsequently, type I PRMTs add an additional methyl group to the same nitrogen atom, resulting in asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), whereas type II PRMTs produce symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA). (B) A schematic illustration of the human PRMT family members. Every contains at least one conserved MTase domain with signature motifs I, post-I, II, and III, along with a THW loop. Additional domains are highlighted: SH3, ZnF (zinc finger), Myr (myristoylation), F-box, TPR (tetratricopeptide), and NosD (nitrous oxidase accessory protein).

Protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) are the enzymes responsible for catalyzing the transfer of methyl groups to arginine residues on target proteins. In mammals, there are 11 known PRMTs [8,9], and they are classified into three types based on the methylation pattern they produce. Type I PRMTs: catalyze the formation of ADMA and MMA [8]. This group includes PRMT1, PRMT2, PRMT3, PRMT4 (also known as CARM1), PRMT6, and PRMT8 [8]. Type II PRMTs: catalyze the formation of SDMA and MMA [8]. This group includes PRMT5, PRMT9 (also known as FBXO11), PRMT10, and PRMT11 (also known as FBXO10). Type III PRMTs: catalyze only MMA. This group includes PRMT7 [8]. These enzymes share common features such as highly conserved methyltransferase domains (Figure 1B) and the use of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) as the methyl donor, and they play crucial roles in various cellular processes, including signal transduction, gene regulation, and RNA metabolism [5,10-12].

PRMT1 and Its Function

PRMT1 is the earliest discovered and most predominant protein arginine methyltransferase [13]. It regulates over 90% of arginine methylation in mammalian cells by catalyzing the methylation of arginine side chains, specifically forming MMA and ADMA [14]. Numerous studies have shown that PRMT1 primarily targets protein substrates with conserved glycine and arginine-rich GAR (RG/RGG/RXG) motifs, which are often located at the C-terminus of proteins [15-17].

PRMT1 is involved in various biological processes by modifying different types of downstream substrates, including, but not limited to, DNA damage repair, gene transcription regulation, and signal transduction abnormalities [18,19]. These activities influence various physiological and pathological processes such as cellular senescence [20], tumorigenesis [21], spermatogenesis [22], and muscle stem cell fate [23].

In the following sections, we will discuss PRMT1's biological role in physiological processes, cancer, and innate immunity.

PRMT1-mediated arginine methylation in physiological processes

PRMT1 is involved in many biological processes through the methylation of different substrates (Table 1). For instance, PRMT1 promotes H3R4 methylation to enhance β-globin transcription [24], regulates cellular senescence [20], and influences spermatogonial stem cell development [22]. It also facilitates DNA damage repair in part through promoting the methylation of 53BP1 [25,26] and MRE11 [25,27].

Furthermore, PRMT1 impacts gene transcription by methylating RUNX1 [28], STAT1 [29], MyoD [30], and TAF15 [31]. Moreover, PRMT1 controls ATXN2L localization by methylation [32]. Additionally, PRMT1 participates in various developmental and functional processes such as pancreatic endocrine development of hESCs [33], muscle stem cell fate determination [23], and the regulation of T cell and macrophage functions [34,35]. Our group found that PRMT1 methylates NPRL2, cooperating with SAMTOR to regulate mTORC1 sensing of methionine [36]. The ever-growing list of PRMT1 downstream substrates demonstrates the critical roles in various cellular processes, which is summarized in (Table 1).

|

Substrate |

Methylation Residues |

Biological outcomes |

Reference |

|

H4 |

R3 |

Facilitates β-globin transcription |

[24] |

|

H4 |

R3 |

Modulation of cellular senescence |

[20] |

|

H4 |

R3 |

Establishment or maintenance chromatin modifications |

[37] |

|

H4 |

R3 |

Spermatogonial development |

[22] |

|

53BP1 |

R1400, 1401, 1403 |

53BP1 DNA binding activity |

[26] |

|

53BP1 |

Unknown |

Facilitates efficient DNA repair |

[25] |

|

MRE11 |

Unknown |

Facilitates efficient DNA repair |

[25] |

|

MRE11 |

R570, 594 |

DNA damage checkpoint control |

[27] |

|

RUNX1 |

R206, 210 |

Abrogates SIN3A binding and potentiates its transcriptional activity |

[28] |

|

STAT1 |

R31 |

Modulates IFN α/β-Induced transcription |

[29] |

|

MyoD |

R121 |

Activates myogenin transcription |

[30] |

|

TAF15 |

R203, 525, 532, R567 |

Positive gene regulatory function |

[31] |

|

NGN3 |

R65 |

Pancreatic endocrine development of hESCs |

[33] |

|

METTL14 |

R255 |

Promotes m6A and mESC endoderm differentiation |

[38] |

|

Klf4 |

R396 |

Restrains the commitment of primitive endoderm |

[39] |

|

Eya1 |

Unknown |

Muscle stem cell fate |

[23] |

|

ASK1 |

R78, 90 |

Regulation of stress-induced signaling |

[40] |

|

BAD |

R94, 96 |

Inhibits Akt-dependent survival signaling |

[41] |

|

PGC-1α |

R665, 667, 669 |

Activation of PGC-1α |

[42] |

|

ERa |

R260 |

Regulation of Estrogen Rapid Signaling |

[43] |

|

EGFR |

R198, 200 |

Regulates signaling and cetuximab response |

[44] |

|

MICU1 |

R455 |

determines the UCP2/3 dependency of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake |

[45] |

|

FOXP3 |

R48, 51 |

Modulate regulatory T cell functions |

[34] |

|

ILF3 |

R609 |

Induces M2 polarization of macrophages |

[35] |

|

IDH2 |

R353 |

Increasing B cell proliferation and antibody production |

[46] |

|

PFKFB3 |

Unknown |

Promotes glycolysis and ensures stress hematopoiesis |

[47] |

|

FoxO1 |

Unknown |

Hepatic glucose production |

[48] |

|

ATXN2L |

Unknown |

Controls ATXN2L localization |

[32] |

|

NPRL2 |

R78 |

Govern mTORC1 methionine sensing |

[36] |

|

UBAP2L |

Unknown |

Stress granule assembly |

[49] |

|

SCYL1 |

R787, 805 |

Golgi morphogenesis |

[50] |

|

RBM15 |

R578 |

RNA splicing |

[51] |

The role of PRMT1-mediated arginine methylation in tumor progression

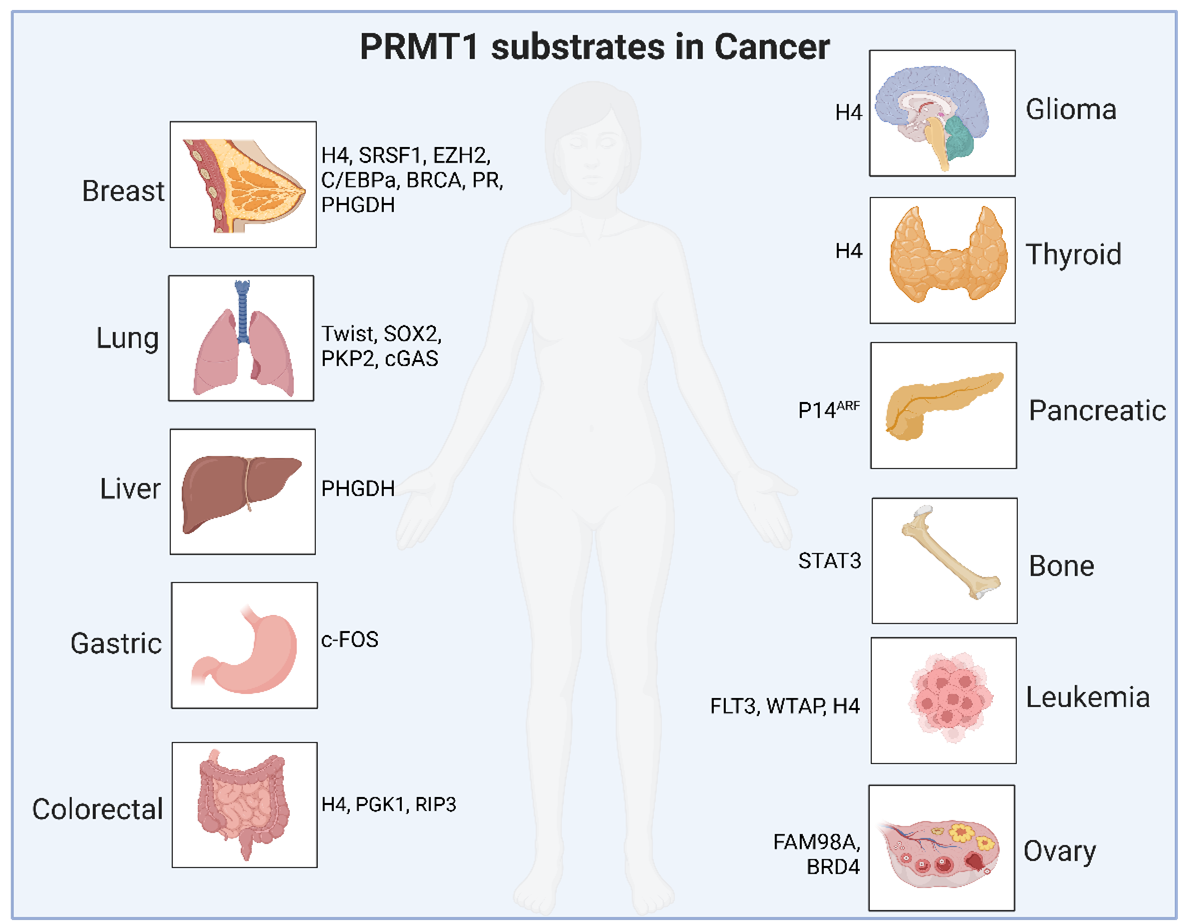

The functions and regulatory mechanisms of PRMT1 in cancer progression have been extensively studied to uncover potential PRMT1-dependent therapeutic strategies, and please refer to the review articles for details [19,21]. Here, we provide a comprehensive overview of the methylation substrates and functions of PRMT1 in various types of human tumors (Figure 2, Table 2) to explore its potential value in cancer therapy.

Figure 2. A schematic summary of PRMT1 downstream methylation substrates in various types of human cancers.

Notably, in breast cancer, PRMT1 promotes tumor cell proliferation, tumorigenesis, and metastasis by methylating substrates such as H4 [52], BRCA1 [53], C/EBPα [54], EZH2 [55-57], Progesterone Receptor (PR) [58], PHGDH [59], and SRSF1 [60]. In lung cancer, PRMT1 methylates and stabilizes cGAS protein levels, thereby promoting NSCLC proliferation [61]; it also methylates TWIST [62] to regulate EMT and methylates PKP2 [63] and SOX2 [64], leading to radioresistance and chemoresistance. In colorectal cancer, the methylation of H4 [65], PGK1 [66], and RIP3 [67] regulates tumor progression and immune evasion. Previously, we found that PRMT1 promotes tumorigenesis by regulating m6A modification levels in part through promoting the methylation of METTL14 at both R442 and R445 residues [68]. PRMT1 is also involved in the progression of the liver [69], osteosarcoma [70], glioma [71], thyroid, pancreatic [72], leukemia [73-76], ovarian [77,78], and gastric [79] cancers by methylating various substrate proteins as summarized in (Table 2). Due to space limits, we will not elaborate on these Arg methylation events and their biological functions here.

|

Cancer type |

Substrate |

Methylation Residues |

Biological outcomes |

Reference |

|

Breast |

H4 |

R3 |

Modulates epithelial mesenchymal transition and cellular senescence |

[52] |

|

SRSF1 |

R93, 97, 109 |

Promotes oncogenic exon inclusion events and breast tumorigenesis |

[60] |

|

|

PR |

R637 |

Promotes cells proliferation and metastasis |

[58] |

|

|

PGHDH |

R20, 54 |

Drives chemoresistance in triple-negative breast cancer |

[59] |

|

|

EZH2 |

R342 |

Promotes cells proliferation, tumorigenesis, and metastasis |

[55-57] |

|

|

C/EBPα |

R35, 156, 165 |

Promotes cancer cells proliferation |

[54] |

|

|

BRCA1 |

Defense cells against ionizing radiation |

[53] |

||

|

Lung |

TWIST1 |

R34 |

Regulates EMT |

[62] |

|

SOX2 |

R90, 98, 113, 115 |

Induces chemoresistance |

[64] |

|

|

Lung |

PKP2 |

R101 |

Participates in radiation resistance |

[63] |

|

cGAS |

R127 |

Stabilize cGAS and promotes NSCLC cell proliferation |

[61] |

|

|

Colorectal |

H4 |

R3 |

Enhances SLC7A11 promoter activity, promotes tumor progression |

[65] |

|

PGK1 |

R206 |

Promotes colorectal cancer glycolysis and tumorigenesis |

[66] |

|

|

RIP3 |

R486 |

Reverts the immune escape of necroptotic colon cancer |

[67] |

|

|

Osteosarcoma |

STAT3 |

R688 |

Promotes tumorigenesis and progression |

[70] |

|

Liver |

PHGDH |

R213 |

Promotes serine synthesis and represents a therapeutic vulnerability |

[69] |

|

Glioma |

H4 |

R3 |

Drives PTX3 and regulates ferritinophagy |

[71] |

|

Thyroid |

H4 |

R3 |

Upregulates ZEB1 and accelerates cell proliferation, migration, and tumor growth |

[80] |

|

Pancreatic |

P14ARF |

R96, 98 |

Promotes the tumor suppressor function of P14ARF |

[81] |

|

GLI1 |

R597 |

Increases oncogenic ability |

[72] |

|

|

Leukemia |

FLT3 |

R972, 973 |

Promotes AML maintenance, disrupts maintenance of MLL-rearranged acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

[73,74] |

|

WTAP |

R272 |

Promotes multiple myeloma tumorigenesis |

[75] |

|

|

H4 |

R3 |

Inhibits ACSL1 expression and ferroptosis |

[76] |

|

|

Ovarian |

FAM98A |

Unknown |

Promotes cancer progression |

[77] |

|

BRD4 |

R179, 181, 183 |

Regulates BRD4 phosphorylation and promotes ovarian cancer invasion |

[78] |

|

|

Gastric |

c-FOS |

R287 |

PRMT1-mediated c-FOS protein stabilization Promotes gastric tumorigenesis |

[79] |

|

INCENP |

R887 |

Promotes mitosis of cancer cells |

[82] |

|

|

METTL14 |

R442, 445 |

Regulates m6A and promotes tumorigenesis |

[68] |

The possible role of PRMT1 in innate immunity

In addition to its involvement in numerous physiological processes and tumor progression through the methylation of various substrates, PRMT1 also plays a crucial role in innate immunity. Studies using CRISPR screening have identified PRMT1 as a negative regulator of CD8+ T cells. Mechanistically, PRMT1 suppresses STAT1, thereby downregulating interferon-gamma (IFN-γ)-induced MHC-I expression [83]. Additionally, Class II transactivator (CIITA) mediates MHC-II expression through IFN-γ. PRMT1 has been found to methylate CIITA, promoting its degradation and thus inhibiting MHC-II transcription [84].

Notably, inhibition of PRMT1 can modulate the enhancer region of DNMT1, increasing levels of H4R3me2a and H3K27ac, which downregulates DNMT1 expression and activates endogenous retrovirus (ERV) transcription and interferon signaling [85]. Besides, our study revealed that PRMT1 methylates the Arg133 residue of the cGAS protein, subsequently preventing its dimerization to inhibit the cGAS-STING pathway [86].

These studies collectively demonstrate that PRMT1 is likely a negative regulator of tumor immunity. Hence, genetic or pharmacological inhibition of PRMT1 can activate type I and type II interferon expression, thereby enhancing the efficacy of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy.

Upstream regulation of PRMT1

Given the crucial role PRMT1 plays in both physiological and pathological conditions, a comprehensive understanding of its regulatory mechanisms is of significant importance. Current research on PRMT1 regulation mainly focuses on upstream pathways that can impact its expression levels and enzymatic activity (Table 3). In LO2 cells, fasting reduces PRMT1 expression via the mTOR-p-STAT signaling pathway, suggesting that mTOR acts as a positive regulator of PRMT1 expression [87]. Additionally, BTG1 serves as a methylation coactivator for PRMT1, enhancing its methylation of ATF4 [88]. Conversely, several mechanisms were found to negatively regulate PRMT1. To this end, PP2A [89], TR3 [90], and hCAF1 [91] inhibit PRMT1's enzymatic activity through direct interaction. Three E3 ubiquitin ligases—E4B [92], CHIP [92,93], and TRIM48 [94]—promote PRMT1 degradation via ubiquitination. Deferoxamine (DFO)/iron deficiency and miR-503 downregulate PRMT1 mRNA levels [95,96]. Despite these known regulators and mechanisms, further research is needed to explore other post-translational modifications of PRMT1, such as phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, and palmitoylation, and their effects on PRMT1's function.

|

Regulator |

Positive |

Negative |

Function |

Reference |

|

E4B |

- |

+ |

Promotes PRMT1 degradation |

[92] |

|

CHIP |

- |

+ |

Promotes PRMT1 degradation |

[92] |

|

PP2A |

- |

+ |

Inhibits PRMT1 enzymatic activity |

[89] |

|

TRIM48 |

- |

+ |

Promotes PRMT1 degradation |

[94] |

|

Deferoxamine (DFO) |

- |

+ |

Down-regulates PRMT1 levels |

[95] |

|

TR3 |

- |

+ |

Inhibits PRMT1 enzymatic activity |

[90] |

|

miR-503 |

- |

+ |

Reduced PRMT1 mRNA levels |

[96] |

|

hCAF1 |

- |

+ |

Inhibits PRMT1 enzymatic activity |

[91] |

|

BTG1 |

+ |

- |

Promotes enzymatic activity |

[88] |

|

mTOR |

+ |

- |

Promotes PRMT1 expression |

[87] |

An Overview of the cGAS-STING Pathway

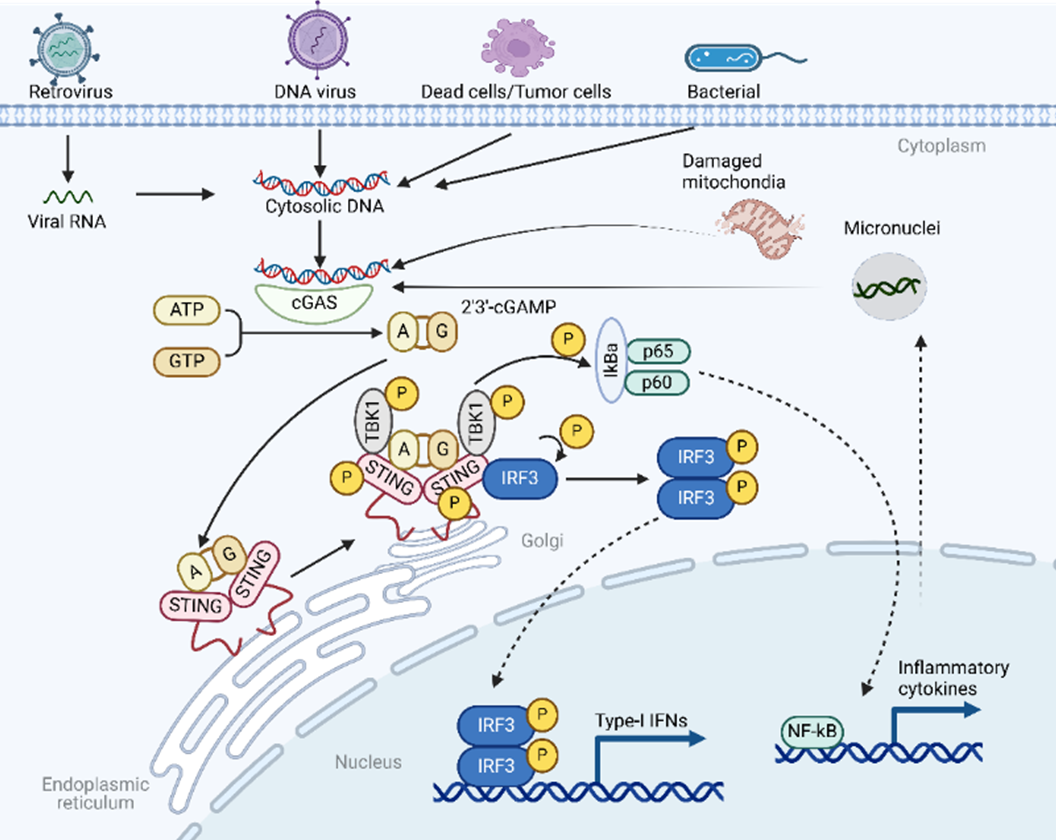

The cGAS-STING pathway is a crucial component of the innate immune system, responsible for detecting cytosolic double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), which indicates infections, cellular damage, or cancer [97]. The pathway initiates when cGAS (cyclic GMP-AMP synthase) binds to dsDNA in the cytoplasm [98]. This binding activates cGAS, allowing it to synthesize cyclic 2’3’-GMP-AMP (cGAMP) from ATP and GTP. The cGAMP acts as a second messenger, binding to the STING (Stimulator of Interferon Genes) protein on the endoplasmic reticulum membrane [98]. This binding induces a conformational change in STING, leading to its activation and translocation to the Golgi apparatus and perinuclear vesicles. Activated STING then recruits TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), which plays a crucial role in downstream signaling [99]. TBK1 phosphorylates interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), causing IRF3 to dimerize and translocate to the nucleus [100]. In the nucleus, IRF3, along with other transcription factors like NF-κB, induces the expression of type I interferons (e.g., IFN-β) and inflammatory cytokines [100]. These molecules are essential for mounting an effective antiviral response and modulating the immune system to address the presence of cytosolic DNA (Figure 3). Through this cascade, the cGAS-STING pathway effectively translates the detection of abnormal cytosolic DNA into a potent immune response, underscoring its importance in antiviral defense, cancer immunity, and its potential role in autoimmune conditions when dysregulated.

Figure 3. A schematic overview of the cGAS-STING-TBK1 signaling pathway.

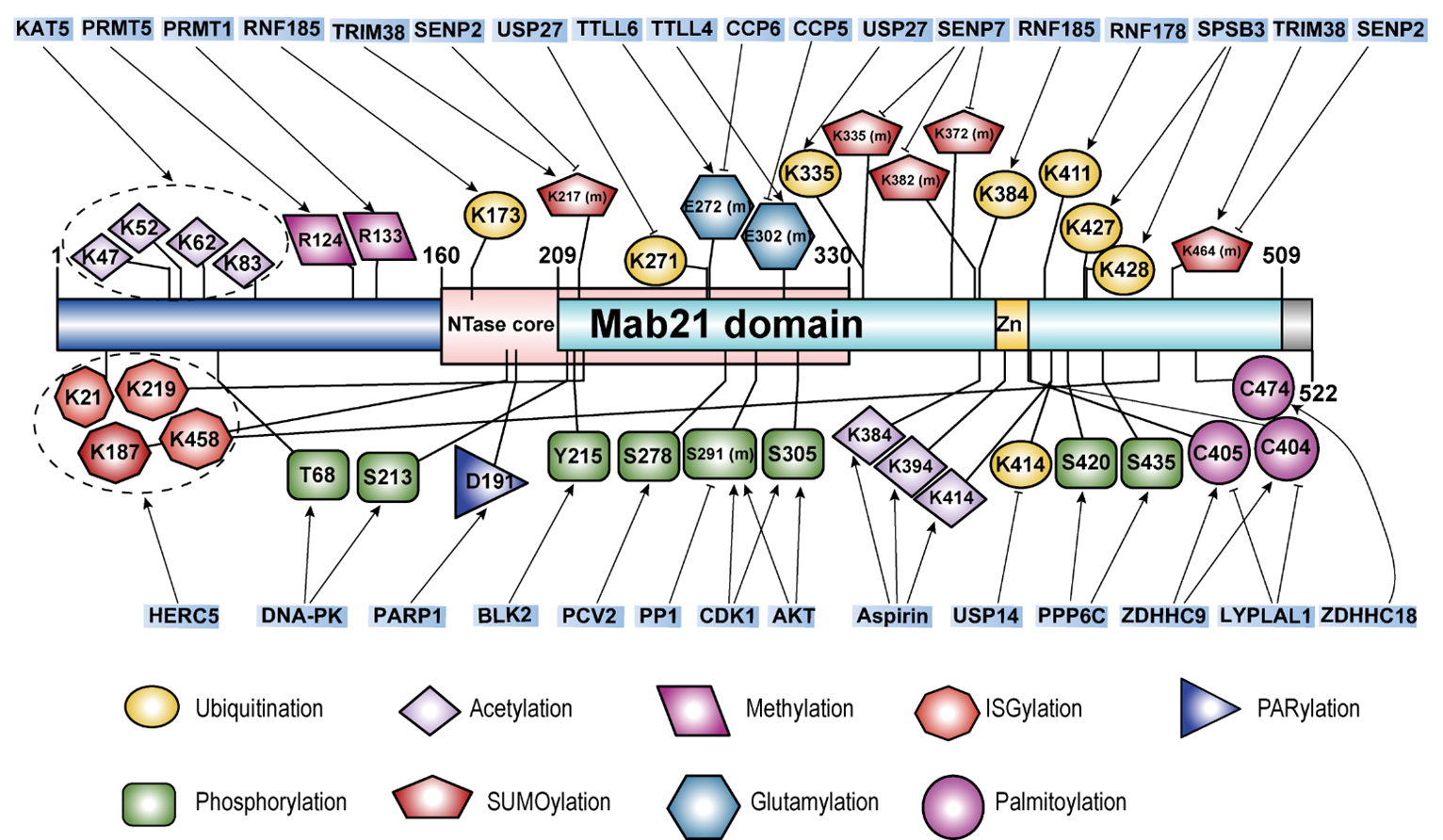

The Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs) of cGAS

Accurate recognition of immunostimulatory DNA by cGAS is crucial for the proper activation of the innate immune response. The post-translational modifications (PTMs) of the cGAS protein are essential for regulating its enzymatic activity and maintaining immune homeostasis under both physiological and pathological conditions. Below, we summarize the known PTMs of cGAS, including ubiquitination (both degradative and non-degradative), phosphorylation, acetylation, SUMOylation, methylation, glutamylation, ISGylation, palmitoylation, and PARylation (Figure 4, Table 4). These PTMs influence various aspects of cGAS cellular function by regulating its enzyme activity, DNA binding, protein stability, and subcellular localization.

Figure 4. A schematic summary of the known protein post-translational modifications (PTMs) of cGAS.

|

PTM type |

Sites |

Mediator |

Function |

Reference |

|

Ubiquitination |

K427, 428 |

SPSB3 |

Targets nuclear cGAS for degradation |

[103] |

|

Unknown |

HBx |

Promotes ubiquitination and autophagy degradation |

[102] |

|

|

Unknown |

TRAF6 |

Activates cGAS signaling |

[104] |

|

|

K173, 384 |

RNF185 |

Promotes cGAS activity |

[105] |

|

|

Unknown |

TRIM41 |

Promotes cGAS activity |

[106] |

|

|

K335 |

TRIM56 |

Increases DNA-binding activity |

[107] |

|

|

K411 |

RNF178 |

Inhibits the DNA binding ability |

[108] |

|

|

Deubiquitination |

K414 |

USP14 |

Stabilizes cGAS |

[111] |

|

Unknown |

USP27x |

Stabilizes cGAS |

[112] |

|

|

K271 |

USP29 |

Stabilizes cGAS |

[113] |

|

|

Phosphorylation |

S291 (m), S305 (h) |

AKT |

Inhibits cGAS activity |

[114] |

|

Y215 |

BLK2 |

Facilitates the cytosolic retention of cGAS |

[116] |

|

|

S291 (m), S305 (h) |

CDK1 |

Inhibits cGAS activity |

[115] |

|

|

T68, S213 |

DNA-PK |

Inhibits cGAS activity |

[117] |

|

|

S278 |

PCV2 |

Inhibits cGAS activity |

[118] |

|

|

Dephosphorylation |

S291 (m) |

PP1 |

Promotes cGAS activity |

[115] |

|

S420 (m), S435 (h) |

PPP6C |

Inhibits cGAS activity |

[119] |

|

|

Acetylation |

K47, 52, 62, 83 |

KAT5 |

Increases DNA-binding activity |

[121] |

|

K384, 394, 414 |

Aspirin |

Blocks cGAS Activity |

[122] |

|

|

SUMOylation |

K217 (m), K464 (m) |

TRIM38 |

Prevents cGAS degradation |

[124] |

|

DeSUMOylation |

K217 (m), K464 (m) |

SENP2 |

Promotes cGAS degradation |

[124] |

|

K335 (m), K372 (m), K382 (m) |

SENP7 |

Potentiates cGAS activation |

[125] |

|

|

Methylation |

R124 |

PRMT5 |

Blocks the DNA binding ability |

[137] |

|

R133 |

PRMT1 |

Prevents cGAS dimerization |

[86] |

|

|

Glutamylation |

E302 (m) |

TTLL4 |

Promotes cGAS activity |

[127] |

|

E272 (m) |

TTLL6 |

Promotes cGAS activity |

[127] |

|

|

Deglutamylation |

E302 (m) |

CCP5 |

Inhibits cGAS activity |

[127] |

|

E272 (m) |

CCP6 |

Inhibits cGAS activity |

[127] |

|

|

ISGylation |

K21, 187, 219, 458 |

HERC5 |

Facilitates cGAS oligomerization |

[131] |

|

Palmitoylation |

C474 |

ZDHHC18 |

Negatively regulateS cGAS activation |

[132] |

|

C404, 405 |

ZDHHC9 |

Facilitates cGAS dimerization and activation |

[133] |

|

|

Depalmitoylation |

C404, 405 |

LYPLAL1 |

Inhibits cGAS activity |

[133] |

|

PARylation |

D191 |

PARP1 |

Inhibits DNA binding ability |

[136] |

Ubiquitination

Ubiquitination is a critical post-translational modification that involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to a target protein. This process affects the protein's stability, interactions, and biological functions and plays a role in cell survival, differentiation, and the regulation of both innate and adaptive immunity [101]. Ubiquitination plays a significant role in regulating cGAS through degradation mechanisms. The Hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) suppresses IFN-I production by directly promoting the ubiquitination and autophagic degradation of cGAS [102]. Furthermore, the CRL5-SPSB3 ubiquitin ligase targets nuclear cGAS for degradation, highlighting the importance of ubiquitination in controlling cGAS levels and activity [103]. Ubiquitination of cGAS also involves non-degradative regulatory mechanisms. Various ubiquitin ligases activate cGAS by mediating different forms of ubiquitin chains, such as TRAF6 (undefined) [104], RNF185 (K27) [105], TRIM41 (mono) [106], and TRIM56 (mono) [107]. Conversely, RNF178 mediates K63-linked ubiquitination, which inhibits the DNA-binding ability of cGAS [108]. Deubiquitination, the process of removing ubiquitin from target proteins, often counteracts the effects of ubiquitination [109,110]. Deubiquitinases like USP14 [111], USP27x [112], and USP29 [113] interact with cGAS to remove K48-linked ubiquitin chains, thereby stabilizing the cGAS protein.

Phosphorylation

Phosphorylation is a key mechanism for regulating protein activity and function, primarily involving the amino acids threonine, serine, and tyrosine. Increasing evidence indicates that phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of cGAS play critical roles in regulating the cGAS-STING signaling pathway. For instance, phosphorylation of cGAS at S291 in mice or S305 in humans, likely mediated by AKT [114] or CDK1 [115], significantly inhibits cGAMP synthesis, while dephosphorylation at these sites by PP1 restores activity. B-lymphoid tyrosine kinase 2 (BLK2) phosphorylates cGAS at Y215, promoting its cytosolic retention [116]. However, DNA damage induces dephosphorylation and nuclear translocation of cGAS. To this end, DNA-PK phosphorylates cGAS at T68 and S213, inhibiting its enzymatic activity [117], whereas PCV2 promotes phosphorylation at S278, leading to ubiquitin-mediated degradation of cGAS [118]. Not all dephosphorylation events activate cGAS; for example, PPP6C dephosphorylates cGAS at S420 in mice or S435 in humans, impairing substrate binding and innate immune response [119]. In summary, phosphorylation and dephosphorylation effectively regulate cGAS enzymatic activity and/or its protein abundance, impacting downstream interferon signaling and highlighting these processes as potential therapeutic targets for various diseases.

Acetylation

Protein acetylation is a post-translational modification where an acetyl group is covalently attached to a protein, typically at lysine residues [120]. This modification can influence protein function, stability, localization, and interactions. The lysine acetyltransferase 5 (KAT5) acetylates multiple lysines at the N-terminus of cGAS (K47, K52, K62, K83), enhancing its DNA binding ability [121]. Conversely, studies have shown that aspirin can directly acetylate cGAS at K384, K394, and K414, leading to its inactivation and the suppression of downstream immune responses mediated by cGAS [122]. HDAC3 can promote the transcription of cGAS by deacetylating P65 [123]. However, there are no reports on the deacetylation of cGAS itself. Overall, more studies are needed to elucidate the impact of dynamic acetylation and deacetylation on the cGAS-STING signaling pathway and innate immune function.

SUMOylation

SUMOylation is a post-translational modification where Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier (SUMO) proteins are attached to lysine residues on target proteins. This modification affects protein function, stability, localization, and interactions. SUMOylation is important for several processes such as nuclear transport, transcription regulation, DNA repair, and signal transduction, helping cells respond to stress and maintain balance. TRIM38 mediates SUMOylation of cGAS at K217 and K464, preventing its polyubiquitination and degradation [124]. Additionally, during viral infection, TRIM38 also SUMOylates STING, promoting its activation and protein stability [124]. Limited studies suggest that SUMOylation at different sites on cGAS has distinct functions. For example, SUMOylation of cGAS can be removed by SENP2, leading to cGAS degradation [124]. Conversely, SENP7 removes SUMOylation at cGAS K335 and K372, thereby activating cGAS [125].

Glutamylation

Glutamylation is an ATP-dependent protein modification that attaches glutamate chains to specific glutamate residues on target proteins. This process is facilitated by tubulin tyrosine ligase (TTL) and tubulin tyrosine ligase-like (TTLL) enzymes [126]. Cytosolic carboxypeptidases (CCPs) can remove these glutamate chains. TTLL4 mediates monoglutamylation of cGAS at E302, inhibiting its synthase activity, while TTLL6 catalyzes polyglutamylation at E272, hindering its ability to bind DNA. Conversely, CCP5 removes monoglutamylation, and CCP6 removes polyglutamylation [127]. During HSV infection, TTLL4 and TTLL6 protein levels are persistently decreased, suggesting that viral infection may trigger regulatory mechanisms affecting these enzymes. Further research is needed to explore these mechanisms.

ISGylation

ISGylation is a post-translational modification where ISG15, a ubiquitin-like protein, is covalently attached to target proteins. ISGylation can modulate protein stability, activity, localization, and interactions, playing a crucial role in antiviral responses and immune regulation [128-130]. A recent study has found that HERC5 catalyzes ISGylation of cytosolic cGAS at K21, K187, K219, and K458 in response to exogenous DNA stimulation [131]. This modification promotes cGAS oligomerization, ultimately enhancing the cGAS-STING antiviral immune response [131].

Palmitoylation

Palmitoylation is a reversible post-translational modification where a palmitoyl group (a 16-carbon fatty acid) is covalently attached to cysteine residues of target proteins via a thioester bond. This modification affects protein membrane localization, stability, trafficking, and function.

ZDHHC18 mediates the palmitoylation of cGAS at C474, which inhibits its dimerization and thereby suppresses its activity [132]. In addition, our collaborative research discovered that ZDHHC9 mediates the palmitoylation of cGAS at C403 and C404, promoting its dimerization and activation [133]. Additionally, lysophospholipase-like 1 (LYPLAL1) can depalmitoylate cGAS, inhibiting its activation [133]. As such, targeting LYPLAL1-mediated cGAS depalmitoylation may enhance cGAS activation, offering a potential strategy to boost anti-tumor immunotherapy efficacy. Studies suggest that palmitoylation is crucial for cGAS dimerization and activation, with different enzymes mediating distinct functions at various sites. This indicates the potential for combining cGAS palmitoylation targeting with immunotherapy to explore new therapeutic possibilities.

PARylation

PARylation is a post-translational modification where ADP-ribose polymers are attached to target proteins. PARylation plays a critical role in various cellular processes, including DNA repair, chromatin remodeling, transcription, and cell death [134, 135]. PARP1 mediates PARylation of human cGAS at D191 or mouse cGAS at E176, which blocks its ability to bind DNA and inhibits the antiviral immune response [136].

Methylation

Protein arginine methylation affects protein function, interactions, and localization, playing a significant role in regulating gene expression, signal transduction, RNA processing, and DNA repair. PRMT5 methylates cGAS at the R124 site, blocking its ability to bind DNA and thereby weakening its antiviral capacity [137]. Oral administration of a PRMT5 inhibitor significantly protected mice from HSV-1 infection and extended their survival [137]. Activating the cGAS/STING innate immune pathway is crucial and effective for anti-tumor immunotherapy. Our research found that PRMT1 methylates the conserved R133 residue of cGAS, preventing its dimerization and further inhibiting cGAS/STING signaling in cancer cells [86]. Notably, genetic inactivation or pharmacological inhibition of PRMT1 led to the activation of cGAS/STING-dependent DNA sensing signals, significantly enhancing the transcription of type I and II interferon response genes [86]. Additionally, PRMT1 inhibition increased the number of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and promoted tumor PD-L1 expression in a cGAS-dependent manner [86]. Consequently, combining PRMT1 inhibitors with anti-PD-1 antibodies in vivo enhanced anti-tumor therapeutic efficacy.

cGAS in Cancer

The role of cGAS in tumors has been extensively studied, revealing its dual function in both promoting and inhibiting tumor progression.

Tumor suppressive functions of cGAS

Immune response enhancement: cGAS primarily functions in the immune response by activating the downstream STING-TBK1 signaling cascade, leading to upregulation of the type I interferons. Deficiencies in the cGAS-STING pathway reduce tumor immunogenicity, lowering the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. For instance, a study on the B16F10 melanoma model showed no tumor growth difference in untreated mice with different genotypes. However, following anti-PD-L1 antibody treatment, the tumor volume in WT mice was significantly reduced, while cGAS-deficient mice showed no significant change [138]. Additionally, reduced cGAS expression correlates with lower survival rates in patients with invasive ductal carcinoma [139].

Inducing cellular senescence and clearance: cGAS inhibits tumorigenesis and progression by promoting tumor cell senescence and clearance. For example, cGAS knockout MEFs exhibits reduced senescence phenotypes compared to WT MEFs [140]. Similarly, cGAS knockout in B16F10 cells resulted in fewer senescent phenotypes [141].

Autophagy and apoptosis: cGAS also suppresses tumors by inducing autophagy and apoptosis in tumor cells [142-145].

Furthermore, some tumors may exploit mechanisms to inhibit the cGAS-STING pathway, thereby evading immune detection and promoting tumor progression. It has been reported that the cGAS-STING pathway is often suppressed in lung adenocarcinoma, colorectal cancer, melanoma, liver cancer, gastric cancer, and telomerase-deficient cancer cells [141,146-150].

Tumor promotive functions of cGAS

cGAS can also promote tumor progression through both STING-dependent and STING-independent mechanisms.

STING-dependent pathways: In MC38 colon tumors and human squamous cell carcinoma, recruitment of regulatory T cells and mobilization of myeloid-derived suppressor cells by the cGAS-STING pathway leads to reduced tumor immunogenicity [151]. In Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC), cGAS-STING promotes immune tolerance in part via activation of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), supporting LLC cell proliferation [152]. Cancer cells can transfer cGAMP to astrocytes via protocadherin seven, activating the STING pathway and forming gap junctions in the brain, promoting tumor growth and metastasis [153].

STING-independent pathways: cGAS acts as an inhibitor of homologous recombination DNA repair by affecting the DNA repair functions of PARP1 and RAD51, thereby compromising genomic stability [116,154,155].

Given these complexities, targeting the cGAS-STING pathway in cancer therapy involves carefully modulating its activity to enhance anti-tumor immunity while minimizing potential pro-tumorigenic effects. Research into PTMs of cGAS, such as methylation, ubiquitination, and phosphorylation, provides further insight into how the activity of cGAS can be fine-tuned to achieve optimal therapeutic outcomes [156,157].

Targeting PRMT1-cGAS-STING Pathway for Anti-Tumor Immunity

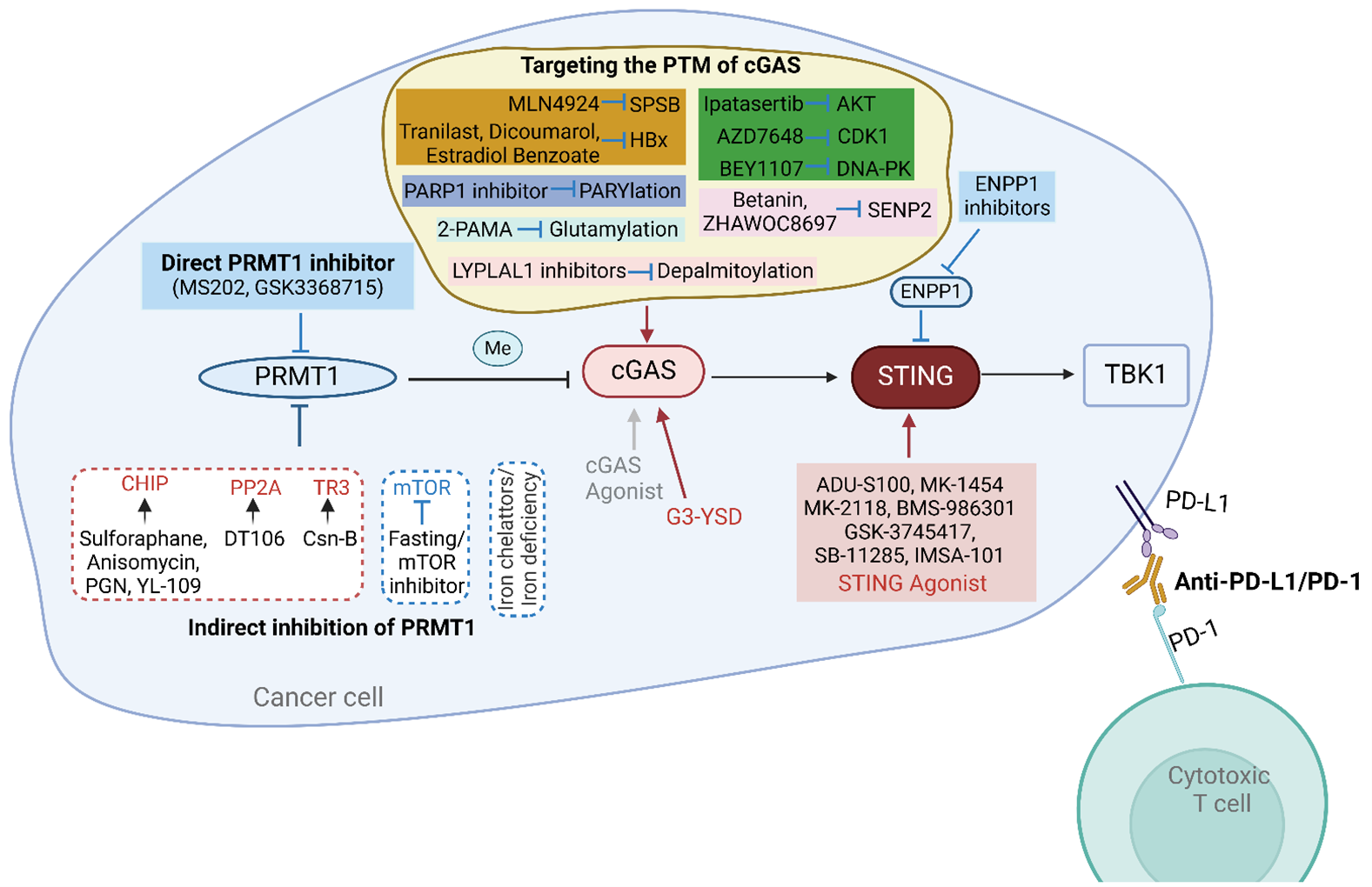

The PRMT1-cGAS-STING pathway is a critical signaling axis in the innate immune response and has significant potential in enhancing anti-tumor immunity. The following strategies can be employed to target this pathway (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Strategies for targeting the PRMT1-cGAS-STING pathway for augmenting anti-tumor immunity.

PRMT1 inhibition

PRMT1 inhibitors: Due to the significant role of PRMT1 in various tumors, it is a viable and worthy drug target for research. Our studies have demonstrated that using existing PRMT1 inhibitors, MS203 and GSK3368715, can activate the expression of type I and II interferon response genes and promote cGAS-dependent immune cell infiltration [86]. Previous research indicates that inhibiting both PRMT1 and PRMT5 can prevent the methylation of cGAS, thereby activating the cGAS-STING pathway and enhancing its downstream immune response [86,137]. Both PRMT1 and PRMT5 are Type I PRMTs, and inhibitors like MS203 and GSK3368715 can restore cGAS activity by simultaneously inhibiting PRMT1 and PRMT5 [86]. Therefore, pharmacological inhibition of PRMT1 is an effective strategy to activate cGAS and enhance anti-tumor immunity. The development of potent and specific PRMT1 inhibitors remains a promising area for research.

Search and development of autoimmune antibodies to PRMT1: Additionally, exploring whether there are autoantibodies against PRMT1 in vivo or developing monoclonal antibodies against PRMT1 could be potential strategies to activate cGAS-mediated immune responses.

Indirect inhibition of PRMT1: Based on the previously summarized regulatory mechanisms of PRMT1, we can aim to inhibit PRMT1 by upregulating or activating its negative regulators and downregulating or inhibiting its positive regulators. Among the numerous negative regulators of PRMT1, CHIP, PP2A, and TR3 have known agonists that enhance their inhibitory effects on PRMT1 activity or protein levels.

Specifically, four known CHIP agonists—Sulforaphane, Anisomycin, Peptidoglycan (PGN), and 2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-benzothiazole (YL-109)—induce CHIP protein overexpression and can serve as potential small-molecule inhibitors of PRMT1 [158]. The PP2A activator DT-061 inhibits tumor progression through various mechanisms, suggesting its potential to inhibit PRMT1 as part of its tumor-suppressing actions [159,160]. Thus, PP2A-activating ligands could be explored as indirect inhibitors of PRMT1 [161]. Cytochrome B (Csn-B), an agonist of TR3 [90], may suppress PRMT1 levels. Furthermore, iron chelators and iron deficiency can effectively reduce PRMT1 levels. Conversely, inhibitors of mTOR and other suppressive measures could also serve as methods to inhibit PRMT1.

Activation of the cGAS-STING-TBK1 pathway

Many types of cancer can induce spontaneous adaptive T-cell responses and promote an immunosuppressive microenvironment that favors tumor progression. Therefore, targeting the cGAS-STING-TBK1 pathway with agonists to “heat up” the tumor microenvironment by secreting interferons and other cytokines can enhance anti-tumor immune responses.

Direct activation of cGAS-STING-TBK1 components: To enhance antitumor immune effects by activating the cGAS-STING-TBK1 signaling pathway, we can use agonists to directly activate each component. Although developing activators for cGAS and TBK1 is reasonable and potentially useful, the focus has mainly been on STING agonists.

In recent years, there has been rapid progress in developing CDN analogs or non-nucleotide small molecules as STING agonists to mimic the function of endogenous 2′,3′-cGAMP [162]. Several compounds (e.g., ADU-S100, MK-1454, MK-2118, BMS-986301, GSK-3745417, SB-11285, IMSA-101) that activate STING are already in clinical studies [162]. However, agonists specifically targeting cGAS and TBK1 are rare. One study showed that G-ended Y-form DNA (G3-YSD) can interact with cGAS to activate the cGAS-STING signaling pathway rather than the RIG-I-MVAS signaling pathway.

Indirect activation of cGAS-STING-TBK1 components: We previously found that cGAS activity and expression levels are regulated by various PTMs. Therefore, targeting these PTMs can indirectly activate cGAS. Inhibitors of different E3 ubiquitin ligases for cGAS can serve as crucial means to activate cGAS by preventing ubiquitination-mediated degradation and activity inhibition. For example, the neddylation inhibitor MLN4924 [163] can indirectly activate cGAS by inhibiting CUL5-SPSB3, thereby increasing nuclear cGAS levels. However, due to its broad impact on substrates, MLN4924 might also affect cellular homeostasis significantly. Several known HBx inhibitors and negative regulators, such as tranilast [164], Dicoumarol [165], and Estradiol Benzoate [166], can serve as means to indirectly activate cGAS. Given the impact of cGAS phosphorylation on its function, inhibitors of AKT1 (ipatasertib) [167], CDK1 (BEY1107) [168], or DNA-PK (AZD7648) [169] can also be used to reactivate cGAS. Using SENP2 inhibitors (Betanin [170], ZHAWOC8697 [171]) may activate cGAS by increasing SUMOylation at K217. The inhibitor 2-phosphonomethylpentanedioic acid (2-PMPA) [172] might activate cGAS by increasing glutamylation. Additionally, PARP1 inhibitors may enhance cGAS DNA-binding ability by inhibiting PARylation at D191. Inhibitors of LYPLAL1 [173] can activate cGAS by preventing depalmitoylation. PRMT1 and PRMT5 inhibitors can restore cGAS activity by inhibiting methylation at different sites, thus boosting antitumor immune responses [86, 137].

Although cGAS undergoes acetylation, SUMOylation, and ISGylation, there are currently no suitable compounds or drugs known to activate cGAS by regulating these modifications.

In addition to directly activating STING, inhibiting the phosphodiesterase ENPP1, a key negative regulator of the STING pathway [174], is another attractive method to enhance STING signaling controllably in certain tumor models. Currently, several small molecules claimed to be orally active ENPP1 inhibitors are entering clinical trials [175-177]. Similarly, targeting the PTMs of STING and TBK1 to indirectly activate this pathway is also an effective strategy; however, this will not be discussed here.

Combination therapy

Since PRMT1 inhibits the cGAS-STING signaling pathway in tumors, methods to directly or indirectly restore cGAS activity and levels can enhance the anti-tumor immune response of cancer cells. Targeting different immune checkpoint pathways (PD-1/PD-L1, CTLA-4) can more effectively block the inhibitory signals used by cancer cells to evade the immune system, thereby enhancing T cell-mediated killing of tumor cells. Our research has found that both inhibitors and or knockdown of PRMT1 can increase PD-L1 expression and significantly improve the anti-PD1 therapy in various mouse tumor models [86]. However, the effects of combining PRMT1 inhibitors with other immune checkpoint inhibitors such as CTLA-4, LAG-3, TIM-3, and TIGIT remain to be determined. Additionally, STING agonist therapy combined with PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade has been shown to enhance the response of high-grade serous ovarian cancer patients to carboplatin chemotherapy [178] and is being evaluated in preclinical models for lymphoma [179]. Moreover, indirect inhibition of PRMT1, as well as targeting the PTM of cGAS, can be combined with each other or with immune checkpoint blockade for effective strategy to enhance the anti-tumor immunity of cancer cells.

Conclusion

The central objective of tumor immunotherapy is to enhance the anti-tumor immunity of cancer cells and facilitate T cell-mediated killing. Activation of innate immune pathways within tumor cells, such as the cGAS-STING and RIG-I-MAVS signaling pathways, is essential to achieve this goal and improve overall anti-tumor immunity. In this review, we focused on the PRMT1-cGAS-STING signaling pathway, detailing the roles of PRMT1 and cGAS, and their PTMs, along with new strategies to activate this pathway, directly or indirectly. Recent studies indicate that targeting this pathway can effectively activate IFN signaling in tumor cells, enhance immune responses, and synergize with PD-1 to improve anti-tumor effects. However, it is necessary to investigate the efficacy of other compounds or drugs that directly activate this pathway or target upstream PTM regulators in combination with PD-1 antibodies to determine their impact on the anti-tumor immune response of tumor cells. This suggests that targeting the PRMT1-cGAS-STING signaling pathway, in conjunction with immune checkpoint inhibitors, is a potentially effective strategy in tumor immunotherapy.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the NIH grants (R35CA253027 to W.W.). We apologize that due to space limitations, not all related studies are included in this review.

Conflict of Interest

W.W. is a co-founder and consultant for the ReKindle Therapeutics. Other authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

2. Nicholson TB, Chen T, Richard S. The physiological and pathophysiological role of PRMT1-mediated protein arginine methylation. Pharmacological Research. 2009;60:466-74.

3. Baldwin GS, Carnegie PR. Specific enzymic methylation of an arginine in the experimental allergic encephalomyelitis protein from human myelin. Science (New York, NY). 1971;171:579-81.

4. Brostoff S, Eylar EH. Localization of methylated arginine in the A1 protein from myelin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1971;68:765-9.

5. Bedford MT, Clarke SG. Protein arginine methylation in mammals: who, what, and why. Molecular Cell. 2009;33:1-13.

6. Bedford MT, Richard S. Arginine methylation an emerging regulator of protein function. Molecular Cell. 2005;18:263-72.

7. Wesche J, Kühn S, Kessler BM, Salton M, Wolf A. Protein arginine methylation: a prominent modification and its demethylation. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences : CMLS. 2017;74:3305-15.

8. Cha B, Jho EH. Protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) as therapeutic targets. Expert opinion on therapeutic targets. 2012;16:651-64.

9. Wu Q, Schapira M, Arrowsmith CH, Barsyte-Lovejoy D. Protein arginine methylation: from enigmatic functions to therapeutic targeting. Nature reviews Drug Discovery. 2021;20:509-30.

10. Guccione E, Richard S. The regulation, functions and clinical relevance of arginine methylation. Nature reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2019; 20: 642-57.

11. Wei H, Mundade R, Lange KC, Lu T. Protein arginine methylation of non-histone proteins and its role in diseases. Cell Cycle (Georgetown, Tex). 2014;13:32-41.

12. Yang Y, Bedford MT. Protein arginine methyltransferases and cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2013;13:37-50.

13. Lin WJ, Gary JD, Yang MC, Clarke S, Herschman HR. The mammalian immediate-early TIS21 protein and the leukemia-associated BTG1 protein interact with a protein-arginine N-methyltransferase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:15034-44.

14. Tang J, Frankel A, Cook RJ, Kim S, Paik WK, Williams KR, et al. PRMT1 is the predominant type I protein arginine methyltransferase in mammalian cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:7723-30.

15. Tang J, Gary JD, Clarke S, Herschman HR. PRMT 3, a type I protein arginine N-methyltransferase that differs from PRMT1 in its oligomerization, subcellular localization, substrate specificity, and regulation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:16935-45.

16. Wooderchak WL, Zang T, Zhou ZS, Acuña M, Tahara SM, Hevel JM. Substrate profiling of PRMT1 reveals amino acid sequences that extend beyond the "RGG" paradigm. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9456-66.

17. Thandapani P, O'Connor TR, Bailey TL, Richard S. Defining the RGG/RG motif. Molecular Cell. 2013;50:613-23.

18. Sudhakar SRN, Khan SN, Clark A, Hendrickson-Rebizant T, Patel S, Lakowski TM, et al. Protein arginine methyltransferase 1, a major regulator of biological processes. Biochemistry and cell biology = Biochimie et Biologie Cellulaire. 2024;102:106-26.

19. Thiebaut C, Eve L, Poulard C, Le Romancer M. Structure, Activity, and Function of PRMT1. Life (Basel, Switzerland). 2021;11.

20. Lin C, Li H, Liu J, Hu Q, Zhang S, Zhang N, et al. Arginine hypomethylation-mediated proteasomal degradation of histone H4-an early biomarker of cellular senescence. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2020;27:2697-709.

21. Shen S, Zhou H, Xiao Z, Zhan S, Tuo Y, Chen D, et al. PRMT1 in human neoplasm: cancer biology and potential therapeutic target. Cell Communication and Signaling :CCS. 2024;22:102.

22. Azhar M, Xu C, Jiang X, Li W, Cao Y, Zhu X, et al. The arginine methyltransferase Prmt1 coordinates the germline arginine methylome essential for spermatogonial homeostasis and male fertility. Nucleic Acids Research. 2023;51:10428-50.

23. Blanc RS, Vogel G, Li X, Yu Z, Li S, Richard S. Arginine Methylation by PRMT1 Regulates Muscle Stem Cell Fate. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2017;37.

24. Li X, Hu X, Patel B, Zhou Z, Liang S, Ybarra R, et al. H4R3 methylation facilitates beta-globin transcription by regulating histone acetyltransferase binding and H3 acetylation. Blood. 2010;115:2028-37.

25. Vadnais C, Chen R, Fraszczak J, Yu Z, Boulais J, Pinder J, et al. GFI1 facilitates efficient DNA repair by regulating PRMT1 dependent methylation of MRE11 and 53BP1. Nature Communications. 2018;9:1418.

26. Boisvert FM, Rhie A, Richard S, Doherty AJ. The GAR motif of 53BP1 is arginine methylated by PRMT1 and is necessary for 53BP1 DNA binding activity. Cell Cycle (Georgetown, Tex). 2005;4:1834-41.

27. Boisvert FM, Déry U, Masson JY, Richard S. Arginine methylation of MRE11 by PRMT1 is required for DNA damage checkpoint control. Genes & Development. 2005;19:671-6.

28. Zhao X, Jankovic V, Gural A, Huang G, Pardanani A, Menendez S, et al. Methylation of RUNX1 by PRMT1 abrogates SIN3A binding and potentiates its transcriptional activity. Genes & Development. 2008;22:640-53.

29. Mowen KA, Tang J, Zhu W, Schurter BT, Shuai K, Herschman HR, et al. Arginine methylation of STAT1 modulates IFNalpha/beta-induced transcription. Cell. 2001;104:731-41.

30. Liu Q, Zhang XL, Cheng MB, Zhang Y. PRMT1 activates myogenin transcription via MyoD arginine methylation at R121. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta Gene Regulatory Mechanisms. 2019;1862:194442.

31. Jobert L, Argentini M, Tora L. PRMT1 mediated methylation of TAF15 is required for its positive gene regulatory function. Experimental Cell Research. 2009;315:1273-86.

32. Kaehler C, Guenther A, Uhlich A, Krobitsch S. PRMT1-mediated arginine methylation controls ATXN2L localization. Experimental Cell Research. 2015;334:114-25.

33. Cho G, Hyun K, Choi J, Shin E, Kim B, Kim H, et al. Arginine 65 methylation of Neurogenin 3 by PRMT1 is required for pancreatic endocrine development of hESCs. Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 2023;55:1506-19.

34. Kagoya Y, Saijo H, Matsunaga Y, Guo T, Saso K, Anczurowski M, et al. Arginine methylation of FOXP3 is crucial for the suppressive function of regulatory T cells. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2019;97:10-21.

35. Zhang Y, Wang K, Yang D, Liu F, Xu X, Feng Y, et al. Hsa_circ_0094606 promotes malignant progression of prostate cancer by inducing M2 polarization of macrophages through PRMT1-mediated arginine methylation of ILF3. Carcinogenesis. 2023;44:15-28.

36. Jiang C, Liu J, He S, Xu W, Huang R, Pan W, et al. PRMT1 orchestrates with SAMTOR to govern mTORC1 methionine sensing via Arg-methylation of NPRL2. Cell Metabolism. 2023;35:2183-99.e7.

37. Huang S, Litt M, Felsenfeld G. Methylation of histone H4 by arginine methyltransferase PRMT1 is essential in vivo for many subsequent histone modifications. Genes & Development. 2005;19:1885-93.

38. Liu X, Wang H, Zhao X, Luo Q, Wang Q, Tan K, et al. Arginine methylation of METTL14 promotes RNA N(6)-methyladenosine modification and endoderm differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature Communications. 2021;12:3780.

39. Zuo ZY, Yang GH, Wang HY, Liu SY, Zhang YJ, Cai Y, et al. Klf4 methylated by Prmt1 restrains the commitment of primitive endoderm. Nucleic Acids Research. 2022;50:2005-18.

40. Cho JH, Lee MK, Yoon KW, Lee J, Cho SG, Choi EJ. Arginine methylation-dependent regulation of ASK1 signaling by PRMT1. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2012;19:859-70.

41. Sakamaki J, Daitoku H, Ueno K, Hagiwara A, Yamagata K, Fukamizu A. Arginine methylation of BCL-2 antagonist of cell death (BAD) counteracts its phosphorylation and inactivation by Akt. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:6085-90.

42. Teyssier C, Ma H, Emter R, Kralli A, Stallcup MR. Activation of nuclear receptor coactivator PGC-1alpha by arginine methylation. Genes & Development. 2005;19:1466-73.

43. Le Romancer M, Treilleux I, Leconte N, Robin-Lespinasse Y, Sentis S, Bouchekioua-Bouzaghou K, et al. Regulation of estrogen rapid signaling through arginine methylation by PRMT1. Molecular Cell. 2008;31:212-21.

44. Liao HW, Hsu JM, Xia W, Wang HL, Wang YN, Chang WC, et al. PRMT1-mediated methylation of the EGF receptor regulates signaling and cetuximab response. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2015;125:4529-43.

45. Madreiter-Sokolowski CT, Klec C, Parichatikanond W, Stryeck S, Gottschalk B, Pulido S, et al. PRMT1-mediated methylation of MICU1 determines the UCP2/3 dependency of mitochondrial Ca(2+) uptake in immortalized cells. Nature Communications. 2016;7:12897.

46. Zhao X, Sun Y, Xu Z, Cai L, Hu Y, Wang H. Targeting PRMT1 prevents acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2023;31:3259-76.

47. Watanuki S, Kobayashi H, Sugiura Y, Yamamoto M, Karigane D, Shiroshita K, et al. Context-dependent modification of PFKFB3 in hematopoietic stem cells promotes anaerobic glycolysis and ensures stress hematopoiesis. ELife. 2024;12.

48. Choi D, Oh KJ, Han HS, Yoon YS, Jung CY, Kim ST, et al. Protein arginine methyltransferase 1 regulates hepatic glucose production in a FoxO1-dependent manner. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md). 2012;56:1546-56.

49. Huang C, Chen Y, Dai H, Zhang H, Xie M, Zhang H, et al. UBAP2L arginine methylation by PRMT1 modulates stress granule assembly. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2020;27:227-41.

50. Amano G, Matsuzaki S, Mori Y, Miyoshi K, Han S, Shikada S, et al. SCYL1 arginine methylation by PRMT1 is essential for neurite outgrowth via Golgi morphogenesis. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2020;31:1963-73.

51. Zhang L, Tran NT, Su H, Wang R, Lu Y, Tang H, et al. Cross-talk between PRMT1-mediated methylation and ubiquitylation on RBM15 controls RNA splicing. ELife. 2015;4.

52. Gao Y, Zhao Y, Zhang J, Lu Y, Liu X, Geng P, et al. The dual function of PRMT1 in modulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cellular senescence in breast cancer cells through regulation of ZEB1. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:19874.

53. Montenegro MF, González-Guerrero R, Sánchez-Del-Campo L, Piñero-Madrona A, Cabezas-Herrera J, Rodríguez-López JN. PRMT1-dependent methylation of BRCA1 contributes to the epigenetic defense of breast cancer cells against ionizing radiation. Scientific Reports. 2020;10:13275.

54. Liu LM, Sun WZ, Fan XZ, Xu YL, Cheng MB, Zhang Y. Methylation of C/EBPα by PRMT1 Inhibits Its Tumor-Suppressive Function in Breast Cancer. Cancer Research. 2019;79:2865-77.

55. Li Z, Wang D, Chen X, Wang W, Wang P, Hou P, et al. PRMT1-mediated EZH2 methylation promotes breast cancer cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Cell Death & Disease. 2021;12:1080.

56. Li Z, Wang D, Lu J, Huang B, Wang Y, Dong M, et al. Methylation of EZH2 by PRMT1 regulates its stability and promotes breast cancer metastasis. Cell death and differentiation. 2020;27:3226-42.

57. Li Z, Wang D, Wang W, Chen X, Tang A, Hou P, et al. Macrophages-stimulated PRMT1-mediated EZH2 methylation promotes breast cancer metastasis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2020;533:679-84.

58. Malbeteau L, Poulard C, Languilaire C, Mikaelian I, Flamant F, Le Romancer M, et al. PRMT1 Is Critical for the Transcriptional Activity and the Stability of the Progesterone Receptor. iScience. 2020;23:101236.

59. Yamamoto T, Hayashida T, Masugi Y, Oshikawa K, Hayakawa N, Itoh M, et al. PRMT1 Sustains De Novo Fatty Acid Synthesis by Methylating PHGDH to Drive Chemoresistance in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Research. 2024;84:1065-83.

60. Li WJ, Huang Y, Lin YA, Zhang BD, Li MY, Zou YQ, et al. Targeting PRMT1-mediated SRSF1 methylation to suppress oncogenic exon inclusion events and breast tumorigenesis. Cell Reports. 2023;42:113385.

61. Liu X, Zheng W, Zhang L, Cao Z, Cong X, Hu Q, et al. Arginine methylation-dependent cGAS stability promotes non-small cell lung cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Letters. 2024;586:216707.

62. Avasarala S, Van Scoyk M, Karuppusamy Rathinam MK, Zerayesus S, Zhao X, Zhang W, et al. PRMT1 Is a Novel Regulator of Epithelial-Mesenchymal-Transition in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2015;290:13479-89.

63. Cheng C, Pei X, Li SW, Yang J, Li C, Tang J, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 library screening uncovered methylated PKP2 as a critical driver of lung cancer radioresistance by stabilizing β-catenin. Oncogene. 2021;40:2842-57.

64. Liang S, Wang Q, Wen Y, Wang Y, Li M, Wang Q, et al. Ligand-independent EphA2 contributes to chemoresistance in small-cell lung cancer by enhancing PRMT1-mediated SOX2 methylation. Cancer Science. 2023;114:921-36.

65. Cao N, Zhang F, Yin J, Zhang J, Bian X, Zheng G, et al. LPCAT2 inhibits colorectal cancer progression via the PRMT1/SLC7A11 axis. Oncogene. 2024;43:1714-25.

66. Liu H, Chen X, Wang P, Chen M, Deng C, Qian X, et al. PRMT1-mediated PGK1 arginine methylation promotes colorectal cancer glycolysis and tumorigenesis. Cell Death & Disease. 2024;15:170.

67. Zhang L, He Y, Jiang Y, Wu Q, Liu Y, Xie Q, et al. PRMT1 reverts the immune escape of necroptotic colon cancer through RIP3 methylation. Cell Death & Disease. 2023;14:233.

68. Wang J, Wang Z, Inuzuka H, Wei W, Liu J. PRMT1 methylates METTL14 to modulate its oncogenic function. Neoplasia (New York, NY). 2023;42:100912.

69. Wang K, Luo L, Fu S, Wang M, Wang Z, Dong L, et al. PHGDH arginine methylation by PRMT1 promotes serine synthesis and represents a therapeutic vulnerability in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature Communications. 2023;14:1011.

70. Yang M, Zhang Y, Liu G, Zhao Z, Li J, Yang L, et al. TIPE1 inhibits osteosarcoma tumorigenesis and progression by regulating PRMT1 mediated STAT3 arginine methylation. Cell Death & Disease. 2022;13:815.

71. Lathoria K, Gowda P, Umdor SB, Patrick S, Suri V, Sen E. PRMT1 driven PTX3 regulates ferritinophagy in glioma. Autophagy. 2023;19:1997-2014.

72. Wang Y, Hsu JM, Kang Y, Wei Y, Lee PC, Chang SJ, et al. Oncogenic Functions of Gli1 in Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Are Supported by Its PRMT1-Mediated Methylation. Cancer Research. 2016;76:7049-58.

73. He X, Zhu Y, Lin YC, Li M, Du J, Dong H, et al. PRMT1-mediated FLT3 arginine methylation promotes maintenance of FLT3-ITD(+) acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2019;134:548-60.

74. Zhu Y, He X, Lin YC, Dong H, Zhang L, Chen X, et al. Targeting PRMT1-mediated FLT3 methylation disrupts maintenance of MLL-rearranged acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2019;134:1257-68.

75. Jia Y, Yu X, Liu R, Shi L, Jin H, Yang D, et al. PRMT1 methylation of WTAP promotes multiple myeloma tumorigenesis by activating oxidative phosphorylation via m6A modification of NDUFS6. Cell Death & Disease. 2023;14:512.

76. Zhou L, Jia X, Shang Y, Sun Y, Liu Z, Liu J, et al. PRMT1 inhibition promotes ferroptosis sensitivity via ACSL1 upregulation in acute myeloid leukemia. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 2023;62:1119-35.

77. Akter KA, Mansour MA, Hyodo T, Ito S, Hamaguchi M, Senga T. FAM98A is a novel substrate of PRMT1 required for tumor cell migration, invasion, and colony formation. Tumour biology : the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2016;37:4531-9.

78. Liu Y, Liu H, Ye M, Jiang M, Chen X, Song G, et al. Methylation of BRD4 by PRMT1 regulates BRD4 phosphorylation and promotes ovarian cancer invasion. Cell Death & Disease. 2023;14:624.

79. Kim E, Rahmawati L, Aziz N, Kim HG, Kim JH, Kim KH, et al. Protection of c-Fos from autophagic degradation by PRMT1-mediated methylation fosters gastric tumorigenesis. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2023;19:3640-60.

80. Feng G, Chen C, Luo Y. PRMT1 accelerates cell proliferation, migration, and tumor growth by upregulating ZEB1/H4R3me2as in thyroid carcinoma. Oncology Reports. 2023;50.

81. Repenning A, Happel D, Bouchard C, Meixner M, Verel-Yilmaz Y, Raifer H, et al. PRMT1 promotes the tumor suppressor function of p14(ARF) and is indicative for pancreatic cancer prognosis. The EMBO Journal. 2021;40:e106777.

82. Deng X, Von Keudell G, Suzuki T, Dohmae N, Nakakido M, Piao L, et al. PRMT1 promotes mitosis of cancer cells through arginine methylation of INCENP. Oncotarget. 2015;6:35173-82.

83. Djajawi TM, Pijpers L, Srivaths A, Chisanga D, Chan KF, Hogg SJ, et al. PRMT1 acts as a suppressor of MHC-I and anti-tumor immunity. Cell Reports. 2024;43:113831.

84. Fan Z, Li J, Li P, Ye Q, Xu H, Wu X, et al. Protein arginine methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1) represses MHC II transcription in macrophages by methylating CIITA. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:40531.

85. Tao H, Jin C, Zhou L, Deng Z, Li X, Dang W, et al. PRMT1 Inhibition Activates the Interferon Pathway to Potentiate Antitumor Immunity and Enhance Checkpoint Blockade Efficacy in Melanoma. Cancer Research. 2024;84:419-33.

86. Liu J, Bu X, Chu C, Dai X, Asara JM, Sicinski P, et al. PRMT1 mediated methylation of cGAS suppresses anti-tumor immunity. Nature Communications. 2023;14:2806.

87. Zhang X, Li L, Li Y, Li Z, Zhai W, Sun Q, et al. mTOR regulates PRMT1 expression and mitochondrial mass through STAT1 phosphorylation in hepatic cell. Biochimica et biophysica acta Molecular Cell Research. 2021;1868:119017.

88. Yuniati L, van der Meer LT, Tijchon E, van Ingen Schenau D, van Emst L, Levers M, et al. Tumor suppressor BTG1 promotes PRMT1-mediated ATF4 function in response to cellular stress. Oncotarget. 2016;7:3128-43.

89. Duong FH, Christen V, Berke JM, Penna SH, Moradpour D, Heim MH. Upregulation of protein phosphatase 2Ac by hepatitis C virus modulates NS3 helicase activity through inhibition of protein arginine methyltransferase 1. Journal of Virology. 2005;79:15342-50.

90. Lei NZ, Zhang XY, Chen HZ, Wang Y, Zhan YY, Zheng ZH, et al. A feedback regulatory loop between methyltransferase PRMT1 and orphan receptor TR3. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37:832-48.

91. Robin-Lespinasse Y, Sentis S, Kolytcheff C, Rostan MC, Corbo L, Le Romancer M. hCAF1, a new regulator of PRMT1-dependent arginine methylation. Journal of cell science. 2007;120:638-47.

92. Bhuripanyo K, Wang Y, Liu X, Zhou L, Liu R, Duong D, et al. Identifying the substrate proteins of U-box E3s E4B and CHIP by orthogonal ubiquitin transfer. Science Advances. 2018;4:e1701393.

93. Jiang L, Liao J, Liu J, Wei Q, Wang Y. Geranylgeranylacetone promotes human osteosarcoma cell apoptosis by inducing the degradation of PRMT1 through the E3 ubiquitin ligase CHIP. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2021;25:7961-72.

94. Hirata Y, Katagiri K, Nagaoka K, Morishita T, Kudoh Y, Hatta T, et al. TRIM48 Promotes ASK1 Activation and Cell Death through Ubiquitination-Dependent Degradation of the ASK1-Negative Regulator PRMT1. Cell Reports. 2017;21:2447-57.

95. Inoue H, Hanawa N, Katsumata SI, Aizawa Y, Katsumata-Tsuboi R, Tanaka M, et al. Iron deficiency negatively regulates protein methylation via the downregulation of protein arginine methyltransferase. Heliyon. 2020;6:e05059.

96. Li B, Liu L, Li X, Wu L. miR-503 suppresses metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma cell by targeting PRMT1. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2015;464:982-7.

97. Decout A, Katz JD, Venkatraman S, Ablasser A. The cGAS-STING pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Nature reviews Immunology. 2021;21:548-69.

98. Ablasser A, Goldeck M, Cavlar T, Deimling T, Witte G, Röhl I, et al. cGAS produces a 2'-5'-linked cyclic dinucleotide second messenger that activates STING. Nature. 2013;498:380-4.

99. Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X, Chen ZJ. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science (New York, NY). 2013;339:786-91.

100. Kato K, Omura H, Ishitani R, Nureki O. Cyclic GMP-AMP as an Endogenous Second Messenger in Innate Immune Signaling by Cytosolic DNA. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2017;86:541-66.

101. Ben-Neriah Y. Regulatory functions of ubiquitination in the immune system. Nature Immunology. 2002;3:20-6.

102. Chen H, Jiang L, Chen S, Hu Q, Huang Y, Wu Y, et al. HBx inhibits DNA sensing signaling pathway via ubiquitination and autophagy of cGAS. Virology Journal. 2022;19:55.

103. Xu P, Liu Y, Liu C, Guey B, Li L, Melenec P, et al. The CRL5-SPSB3 ubiquitin ligase targets nuclear cGAS for degradation. Nature. 2024;627:873-9.

104. Chen X, Chen Y. Ubiquitination of cGAS by TRAF6 regulates anti-DNA viral innate immune responses. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2019;514:659-64.

105. Wang Q, Huang L, Hong Z, Lv Z, Mao Z, Tang Y, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF185 facilitates the cGAS-mediated innate immune response. PLoS Pathogens. 2017;13:e1006264.

106. Liu ZS, Zhang ZY, Cai H, Zhao M, Mao J, Dai J, et al. RINCK-mediated monoubiquitination of cGAS promotes antiviral innate immune responses. Cell & Bioscience. 2018;8:35.

107. Seo GJ, Kim C, Shin WJ, Sklan EH, Eoh H, Jung JU. TRIM56-mediated monoubiquitination of cGAS for cytosolic DNA sensing. Nature Communications. 2018;9:613.

108. Yang X, Shi C, Li H, Shen S, Su C, Yin H. MARCH8 attenuates cGAS-mediated innate immune responses through ubiquitylation. Science Signaling. 2022;15:eabk3067.

109. Hsu SK, Chou CK, Lin IL, Chang WT, Kuo IY, Chiu CC. Deubiquitinating enzymes: potential regulators of the tumor microenvironment and implications for immune evasion. Cell Communication and Signaling :CCS. 2024;22:259.

110. Cheng J, Guo J, North BJ, Wang B, Cui CP, Li H, et al. Functional analysis of deubiquitylating enzymes in tumorigenesis and development. Biochimica et biophysica acta Reviews on Cancer. 2019;1872:188312.

111. Chen M, Meng Q, Qin Y, Liang P, Tan P, He L, et al. TRIM14 Inhibits cGAS Degradation Mediated by Selective Autophagy Receptor p62 to Promote Innate Immune Responses. Molecular Cell. 2016;64:105-19.

112. Guo Y, Jiang F, Kong L, Li B, Yang Y, Zhang L, et al. Cutting Edge: USP27X Deubiquitinates and Stabilizes the DNA Sensor cGAS to Regulate Cytosolic DNA-Mediated Signaling. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2019;203:2049-54.

113. Zhang Q, Tang Z, An R, Ye L, Zhong B. USP29 maintains the stability of cGAS and promotes cellular antiviral responses and autoimmunity. Cell Research. 2020;30:914-27.

114. Seo GJ, Yang A, Tan B, Kim S, Liang Q, Choi Y, et al. Akt Kinase-Mediated Checkpoint of cGAS DNA Sensing Pathway. Cell Reports. 2015;13:440-9.

115. Zhong L, Hu MM, Bian LJ, Liu Y, Chen Q, Shu HB. Phosphorylation of cGAS by CDK1 impairs self-DNA sensing in mitosis. Cell Discovery. 2020;6:26.

116. Liu H, Zhang H, Wu X, Ma D, Wu J, Wang L, et al. Nuclear cGAS suppresses DNA repair and promotes tumorigenesis. Nature. 2018;563:131-6.

117. Sun X, Liu T, Zhao J, Xia H, Xie J, Guo Y, et al. DNA-PK deficiency potentiates cGAS-mediated antiviral innate immunity. Nature Communications. 2020;11:6182.

118. Wang Z, Chen J, Wu X, Ma D, Zhang X, Li R, et al. PCV2 targets cGAS to inhibit type I interferon induction to promote other DNA virus infection. PLoS Pathogens. 2021;17:e1009940.

119. Li M, Shu HB. Dephosphorylation of cGAS by PPP6C impairs its substrate binding activity and innate antiviral response. Protein & Cell. 2020;11:584-99.

120. Dang F, Wei W. Targeting the acetylation signaling pathway in cancer therapy. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2022;85:209-18.

121. Song ZM, Lin H, Yi XM, Guo W, Hu MM, Shu HB. KAT5 acetylates cGAS to promote innate immune response to DNA virus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2020;117:21568-75.

122. Dai J, Huang YJ, He X, Zhao M, Wang X, Liu ZS, et al. Acetylation Blocks cGAS Activity and Inhibits Self-DNA-Induced Autoimmunity. Cell. 2019;176:1447-60.e14.

123. Liao Y, Cheng J, Kong X, Li S, Li X, Zhang M, et al. HDAC3 inhibition ameliorates ischemia/reperfusion-induced brain injury by regulating the microglial cGAS-STING pathway. Theranostics. 2020;10:9644-62.

124. Hu MM, Yang Q, Xie XQ, Liao CY, Lin H, Liu TT, et al. Sumoylation Promotes the Stability of the DNA Sensor cGAS and the Adaptor STING to Regulate the Kinetics of Response to DNA Virus. Immunity. 2016;45:555-69.

125. Cui Y, Yu H, Zheng X, Peng R, Wang Q, Zhou Y, et al. SENP7 Potentiates cGAS Activation by Relieving SUMO-Mediated Inhibition of Cytosolic DNA Sensing. PLoS pathogens. 2017;13:e1006156.

126. Garnham CP, Vemu A, Wilson-Kubalek EM, Yu I, Szyk A, Lander GC, et al. Multivalent Microtubule Recognition by Tubulin Tyrosine Ligase-like Family Glutamylases. Cell. 2015;161:1112-23.

127. Xia P, Ye B, Wang S, Zhu X, Du Y, Xiong Z, et al. Glutamylation of the DNA sensor cGAS regulates its binding and synthase activity in antiviral immunity. Nature Immunology. 2016;17:369-78.

128. Mathieu NA, Paparisto E, Barr SD, Spratt DE. HERC5 and the ISGylation Pathway: Critical Modulators of the Antiviral Immune Response. Viruses. 2021;13.

129. Albert M, Bécares M, Falqui M, Fernández-Lozano C, Guerra S. ISG15, a Small Molecule with Huge Implications: Regulation of Mitochondrial Homeostasis. Viruses. 2018;10.

130. Zhang M, Li J, Yan H, Huang J, Wang F, Liu T, et al. ISGylation in Innate Antiviral Immunity and Pathogen Defense Responses: A Review. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2021;9:788410.

131. Chu L, Qian L, Chen Y, Duan S, Ding M, Sun W, et al. HERC5-catalyzed ISGylation potentiates cGAS-mediated innate immunity. Cell Reports. 2024;43:113870.

132. Shi C, Yang X, Liu Y, Li H, Chu H, Li G, et al. ZDHHC18 negatively regulates cGAS-mediated innate immunity through palmitoylation. The EMBO Journal. 2022;41:e109272.

133. Fan Y, Gao Y, Nie L, Hou T, Dan W, Wang Z, et al. Targeting LYPLAL1-mediated cGAS depalmitoylation enhances the response to anti-tumor immunotherapy. Molecular Cell. 2023;83:3520-32.e7.

134. Ray Chaudhuri A, Nussenzweig A. The multifaceted roles of PARP1 in DNA repair and chromatin remodelling. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2017;18:610-21.

135. Kang M, Park S, Park SH, Lee HG, Park JH. A Double-Edged Sword: The Two Faces of PARylation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23.

136. Wang F, Zhao M, Chang B, Zhou Y, Wu X, Ma M, et al. Cytoplasmic PARP1 links the genome instability to the inhibition of antiviral immunity through PARylating cGAS. Molecular Cell. 2022;82:2032-49.e7.

137. Ma D, Yang M, Wang Q, Sun C, Shi H, Jing W, et al. Arginine methyltransferase PRMT5 negatively regulates cGAS-mediated antiviral immune response. Science Advances. 2021;7.

138. Wang H, Hu S, Chen X, Shi H, Chen C, Sun L, et al. cGAS is essential for the antitumor effect of immune checkpoint blockade. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2017;114:1637-42.

139. Wu MZ, Cheng WC, Chen SF, Nieh S, O'Connor C, Liu CL, et al. miR-25/93 mediates hypoxia-induced immunosuppression by repressing cGAS. Nature Cell Biology. 2017;19:1286-96.

140. Glück S, Guey B, Gulen MF, Wolter K, Kang TW, Schmacke NA, et al. Innate immune sensing of cytosolic chromatin fragments through cGAS promotes senescence. Nature Cell Biology. 2017;19:1061-70.

141. Yang H, Wang H, Ren J, Chen Q, Chen ZJ. cGAS is essential for cellular senescence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2017;114:E4612-e20.

142. Zierhut C, Yamaguchi N, Paredes M, Luo JD, Carroll T, Funabiki H. The Cytoplasmic DNA Sensor cGAS Promotes Mitotic Cell Death. Cell. 2019;178:302-15.e23.

143. Li C, Liu W, Wang F, Hayashi T, Mizuno K, Hattori S, et al. DNA damage-triggered activation of cGAS-STING pathway induces apoptosis in human keratinocyte HaCaT cells. Molecular Immunology. 2021;131:180-90.

144. Thomsen MK, Skouboe MK, Boularan C, Vernejoul F, Lioux T, Leknes SL, et al. The cGAS-STING pathway is a therapeutic target in a preclinical model of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2020;39:1652-64.

145. Liang Q, Seo GJ, Choi YJ, Kwak MJ, Ge J, Rodgers MA, et al. Crosstalk between the cGAS DNA sensor and Beclin-1 autophagy protein shapes innate antimicrobial immune responses. Cell Host & Microbe. 2014;15:228-38.

146. Xia T, Konno H, Barber GN. Recurrent Loss of STING Signaling in Melanoma Correlates with Susceptibility to Viral Oncolysis. Cancer Research. 2016;76:6747-59.

147. Xia T, Konno H, Ahn J, Barber GN. Deregulation of STING Signaling in Colorectal Carcinoma Constrains DNA Damage Responses and Correlates With Tumorigenesis. Cell Reports. 2016;14:282-97.

148. Bu Y, Liu F, Jia QA, Yu SN. Decreased Expression of TMEM173 Predicts Poor Prognosis in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PloS One. 2016;11:e0165681.

149. Song S, Peng P, Tang Z, Zhao J, Wu W, Li H, et al. Decreased expression of STING predicts poor prognosis in patients with gastric cancer. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:39858.

150. Raaby Gammelgaard K, Sandfeld-Paulsen B, Godsk SH, Demuth C, Meldgaard P, Sorensen BS, et al. cGAS-STING pathway expression as a prognostic tool in NSCLC. Translational Lung Cancer Research. 2021;10:340-54.

151. Liang H, Deng L, Hou Y, Meng X, Huang X, Rao E, et al. Host STING-dependent MDSC mobilization drives extrinsic radiation resistance. Nature Communications. 2017;8:1736.

152. Lemos H, Mohamed E, Huang L, Ou R, Pacholczyk G, Arbab AS, et al. STING Promotes the Growth of Tumors Characterized by Low Antigenicity via IDO Activation. Cancer Research. 2016;76:2076-81.

153. Chen Q, Boire A, Jin X, Valiente M, Er EE, Lopez-Soto A, et al. Carcinoma-astrocyte gap junctions promote brain metastasis by cGAMP transfer. Nature. 2016;533:493-8.

154. Jiang H, Xue X, Panda S, Kawale A, Hooy RM, Liang F, et al. Chromatin-bound cGAS is an inhibitor of DNA repair and hence accelerates genome destabilization and cell death. The EMBO Journal. 2019;38:e102718.

155. Ceccaldi R, Rondinelli B, D'Andrea AD. Repair Pathway Choices and Consequences at the Double-Strand Break. Trends in Cell Biology. 2016;26:52-64.

156. Zhu Q, Man SM, Gurung P, Liu Z, Vogel P, Lamkanfi M, et al. Cutting edge: STING mediates protection against colorectal tumorigenesis by governing the magnitude of intestinal inflammation. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2014;193:4779-82.

157. Hopfner KP, Hornung V. Molecular mechanisms and cellular functions of cGAS-STING signalling. Nature reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2020;21:501-21.

158. Zhang S, Hu ZW, Mao CY, Shi CH, Xu YM. CHIP as a therapeutic target for neurological diseases. Cell Death & Disease. 2020;11:727.

159. Jayappa KD, Tran B, Gordon VL, Morris C, Saha S, Farrington CC, et al. PP2A modulation overcomes multidrug resistance in chronic lymphocytic leukemia via mPTP-dependent apoptosis. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2023;133.

160. Rasool RU, O'Connor CM, Das CK, Alhusayan M, Verma BK, Islam S, et al. Loss of LCMT1 and biased protein phosphatase 2A heterotrimerization drive prostate cancer progression and therapy resistance. Nature Communications. 2023;14:5253.

161. Lorrio S, Romero A, González-Lafuente L, Lajarín-Cuesta R, Martínez-Sanz FJ, Estrada M, et al. PP2A ligand ITH12246 protects against memory impairment and focal cerebral ischemia in mice. ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 2013;4:1267-77.

162. Ding C, Song Z, Shen A, Chen T, Zhang A. Small molecules targeting the innate immune cGAS‒STING‒TBK1 signaling pathway. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2020;10:2272-98.

163. Soucy TA, Smith PG, Milhollen MA, Berger AJ, Gavin JM, Adhikari S, et al. An inhibitor of NEDD8-activating enzyme as a new approach to treat cancer. Nature. 2009;458:732-6.

164. Ma Y, Nakamoto S, Ao J, Qiang N, Kogure T, Ogawa K, et al. Antiviral Compounds Screening Targeting HBx Protein of the Hepatitis B Virus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23.

165. Cheng ST, Hu JL, Ren JH, Yu HB, Zhong S, Wai Wong VK, et al. Dicoumarol, an NQO1 inhibitor, blocks cccDNA transcription by promoting degradation of HBx. Journal of Hepatology. 2021;74:522-34.

166. He J, Wu J, Chen J, Zhang S, Guo Y, Zhang X, et al. Identification of Estradiol Benzoate as an Inhibitor of HBx Using Inducible Stably Transfected HepG2 Cells Expressing HiBiT Tagged HBx. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 2022;27.

167. Mullard A. FDA approves first-in-class AKT inhibitor. Nature Reviews Drug discovery. 2024;23:9.

168. Wang Q, Bode AM, Zhang T. Targeting CDK1 in cancer: mechanisms and implications. NPJ Precision Oncology. 2023;7:58.

169. Fok JHL, Ramos-Montoya A, Vazquez-Chantada M, Wijnhoven PWG, Follia V, James N, et al. AZD7648 is a potent and selective DNA-PK inhibitor that enhances radiation, chemotherapy and olaparib activity. Nature Communications. 2019;10:5065.

170. Taghvaei S, Sabouni F, Minuchehr Z. Identification of Natural Products as SENP2 Inhibitors for Targeted Therapy in Heart Failure. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2022;13:817990.

171. Brand M, Bommeli EB, Rütimann M, Lindenmann U, Riedl R. Discovery of a Dual SENP1 and SENP2 Inhibitor. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23.

172. Wang R, Lin L, Zheng Y, Cao P, Yuchi Z, Wu HY. Identification of 2-PMPA as a novel inhibitor of cytosolic carboxypeptidases. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2020;533:1393-9.

173. Ahn K, Boehm M, Brown MF, Calloway J, Che Y, Chen J, et al. Discovery of a Selective Covalent Inhibitor of Lysophospholipase-like 1 (LYPLAL1) as a Tool to Evaluate the Role of this Serine Hydrolase in Metabolism. ACS Chemical Biology. 2016;11:2529-40.

174. Lanng KRB, Lauridsen EL, Jakobsen MR. The balance of STING signaling orchestrates immunity in cancer. Nature Immunology. 2024;25:1144-57.