Abstract

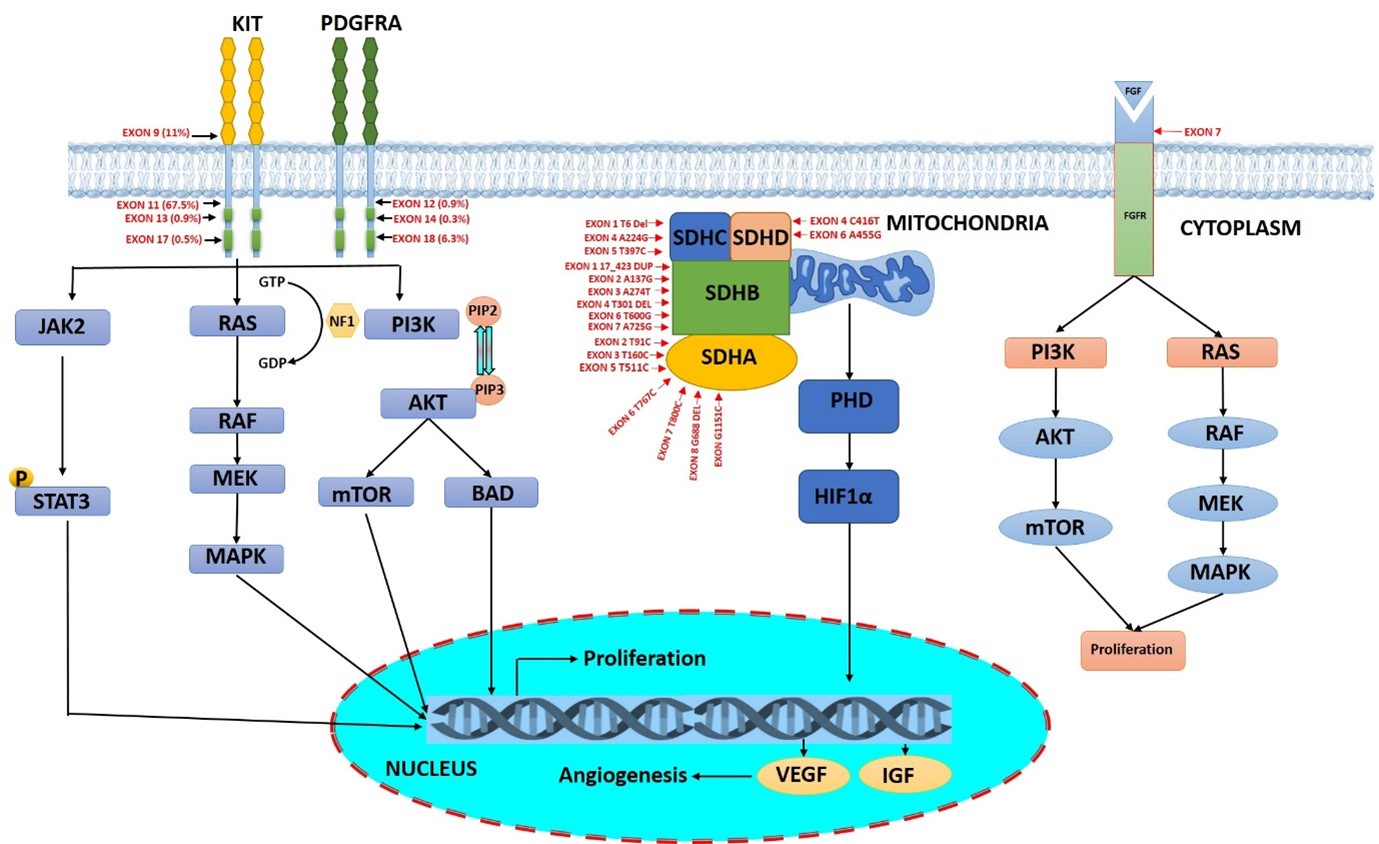

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors are mesenchymal tumors which predominantly originate from the interstitial cells of Cajal in the intestinal lining. Around ~85% of malignant GISTs possess activating mutations in the tyrosine kinase receptors KIT or PDGFRA. The driver mutations in genes other than KIT or PDGFRA account for around 15% GISTs and belong to highly heterogeneous groups called wild-type GISTs. Around 20–40% of WT-GISTS are deficient for the succinate dehydrogenase complex (SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD). Mutations in SDH cause the accumulation of oncometabolite succinate that increases the level of HIF1α which enhances the transcription of several genes including IGF1, IGF2, and VEGF inducing the proliferation of the cancer cells. The remaining WT-GISTS are associated with mutations in BRAF, loss-of-function of NF1, hyperactivation FGFR, inactivation of tumor suppressor genes (p53 and dystrophin), and mutations in DNA damage response genes such as RAD51 and BRCA2 which results in the activation of the PI3K/mTOR or RAS/RAF/MAPK signaling cascade. Therefore, understanding the mutational status and molecular characterization of GIST plays a very crucial role in the overall management of GIST.

Keywords

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor, Gene mutation, PDGFRA, KIT, SDH, Tumor suppressor gene

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most dreadful sarcomas of the soft tissues in the gastrointestinal tract [1,2]. Globally, it is estimated that the prevalence of GISTs is 13 people per 100,000 with a median age of around 60–65 years [3]. GISTs frequently develop in the stomach (51%) and then the small intestine (36%), colon (7%), and rectum (5%). GISTs originate from the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), which are the critical pacemaker cells of the gastrointestinal tract to coordinate the peristaltic movement [4]. GISTs commonly occur due to the gain of function oncogenic mutations in the platelet-derived growth factor alpha (PDGFRA) or v-kit Hardy–Zuckerman 4 feline sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KIT) genes that constitutively activate the tyrosine kinase receptor [4,5]. Activation of PDGFRA or KIT upregulates the downstream signaling pathways such as RAS/RAF/MAPK, thereby inducing uncontrolled cell proliferation, inhibition of apoptosis, angiogenesis, and differentiation. Furthermore, KIT-dependent activation of PI3K/mTOR signaling is crucial for early tumor development in GIST [6,7]. KIT protein, also referred to as stem-cell growth factor receptor [8], is mutated in 70–75% of GIST cases, whereas the structurally similar PDGFRA kinase is mutated in 5–7 % of cases [9,10]. About 10–15% of the cases which do not possess the KIT or PDGFRA driver mutations are called wild-type GISTs (WT) [11]. The loss of function succinate dehydrogenase mutant (SDH), accounts for the 20% to 40% of the WT GISTs [12]. The SDH-deficient GISTs exhibit global genomic hypermethylation due to the loss of the SDH complex [13]. Furthermore, WT GISTs also include MAPK pathway hyperactivation and mutations in the kinases N-RAS, B-RAF V600E, PIK3, H-RAS, and N-TRK (Figure 1) [11]. The KIT gene is commonly mutated in exons 11, 9, 13, and 17 whereas mutations of the PDGFRA gene include exons 12, 14, or 18 [14,15]. For inoperable GISTs, the commonly used chemotherapeutic drug is tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib. Even Though GISTs initially respond positively to imatinib, around 85% of GIST patients gradually gain resistance to the therapy due to the mutations in KIT and PDGFRA genes. The aim of this article is to report all the mutations in the genes involved in GISTs, for the future understanding of this highly heterogeneous tumor.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of critical gene mutation in KIT, PDGFRA, SDH, and FGF associated with GISTs.

Tumor-Related Gene Mutations in GISTs

GISTs develop majorly due to the gain of function mutation in the tumor driving genes namely, KIT or PDGFRA. Mutational analysis of KIT-associated GISTs using whole exome sequencing (WES) revealed various missense mutations in the genes related to DNA repair pathways. Deficiency in DNA repair due to mutations in the genes namely, MLH1, MSH6, POLE, BRCA1, and BRCA2 induces the progression of GISTs (Table 1). Missense mutations are frequently observed in the insulin metabolism-associated genes namely INSR, IRS1, and IRS2. In addition to its role in type II diabetes and insulin resistance, mutant IRS1 also triggers malignancy by upregulating the ErbB-PI3K-AKT signaling pathway [16]. Mutational activation of KIT/PDGFRA downstream genes namely; TSC1, mTOR, FLT4, BRCA1, TSC1, and TSC2 plays a crucial role in the resistance to imatinib and other KIT inhibitors [6]. Notably, several studies have reported the role of missense mutation L148P ARF1 in metastatic and relapsed GIST tumor, however, its molecular mechanism still remains unclear and deserves further investigation [17,18].

|

GENE |

CHROMOSOME |

MUTATION SITE |

MUTATION TYPE |

REFERENCE |

|

KIT |

chr 4q12 |

Exon 9 A502_Y503 |

Duplication- insertion |

[19] |

|

chr 4q12 |

Exon 11 Codon 557-559 |

Deletion or insertion |

||

|

chr 4q12 |

Exon 13 V654A |

Point mutation |

||

|

chr 4q12 |

Exon 14 T670I |

Substitution |

[20] |

|

|

chr 4q12 |

Exon 17 I808T/I808L |

Point mutation |

||

|

PDGFRA |

chr 4q12 |

Exon 18 D842_H845 |

Deletion |

[19] |

|

chr 4q12 |

Exon 12 Codon 561-571 |

Deletion /insertion |

||

|

chr 4q12 |

Exon 14 N659K |

Point mutation |

||

|

SDHA |

chr 5p15 |

Exon 2 T91C |

Point mutation |

[21] |

|

chr 5p15 |

Exon 3 T160C |

Point mutation |

[22] |

|

|

chr 5p15 |

Exon 5 T511C |

Point mutation |

[23] |

|

|

chr 5p15 |

Exon 6 T767C |

Point mutation |

[21] |

|

|

chr 5p15 |

Exon 7 T800C |

Point mutation |

[22] |

|

|

chr 5p15 |

Exon 8 G688 |

Deletion |

[24] |

|

|

chr 5p15 |

Exon 9 G1151C |

Point mutation |

[25] |

|

|

SDHB |

chr 1p36 |

Exon 1 Codon 17_42 |

Duplication |

[21] |

|

chr 1p36 |

Exon 2 A137G |

Point mutation |

||

|

chr 1p36 |

Exon 3 A274T |

Point mutation |

||

|

chr 1p36 |

Exon 4 T301 |

Deletion |

[23] |

|

|

chr 1p36 |

Exon 6 T600G |

Point mutation |

[21] |

|

|

chr 1p36 |

Exon 7 A725G |

Point mutation |

[26] |

|

|

SDHC |

chr 1q23 |

Exon 1 T6 |

Deletion |

[21] |

|

chr 1q23 |

Exon 4 A224G |

Point mutation |

||

|

chr 1q23 |

Exon 5 T397C |

Point mutation |

[26] |

|

|

SDHD |

chr 11q23 |

Exon 6 A455G |

Point mutation |

[23] |

|

chr 11q23 |

Exon 4 C416T |

Point mutation |

[27] |

|

|

FGFR1 |

chr 8p11.2 |

Exon 7 N546K |

Point mutation |

[28] |

|

AXIN2 |

chr17 |

G863C |

Missense |

[18] |

|

BRCA1 |

chr17 |

T2425C |

Missense |

|

|

CDK12 |

chr17 |

G253T |

Missense |

|

|

EGFL7 |

chr9 |

C745T |

Missense |

|

|

FOXA1 |

chr14 |

A77G |

Missense |

|

|

IGF1R |

chr15 |

G3506C |

Missense |

|

|

INSR |

chr19 |

A3028G |

Missense |

|

|

IRS1 |

chr2 |

C1360T |

Missense |

|

|

IRS2 |

chr13 |

C2668G |

Missense |

|

|

MLH1 |

chr3 |

C649T |

Missense |

|

|

PAX5 |

chr9 |

A50G |

Missense |

|

|

PTPRS |

chr19 |

T886A |

Missense |

|

|

POLE |

chr 12 |

V551I |

Missense |

|

|

RFWD2 |

chr1 |

G1098C |

Missense |

|

|

SOX17 |

chr8 |

C277G |

Missense |

|

|

ARID1B |

chr6 |

G617A |

Missense |

|

|

DNMT1 |

chr19 |

G4027A |

Missense |

|

|

EPHB1 |

chr3 |

C979T |

Missense |

|

|

FAT1 |

chr4 |

G4535A |

Missense |

|

|

HNF1A |

chr12 |

C832T |

Missense |

|

|

ARF1 |

chr 1 |

L148P |

Missense |

|

|

MSH6 |

chr 2 |

K724M |

Missense |

Mutations in KIT and PDGFRA associated GIST

GISTs commonly have a gain of function oncogenic mutations in KIT or PDGFRA receptor tyrosine kinase [29]. Stimulation of KIT by stem cell factor upregulates cellular functions including proliferation, apoptosis, and chemotaxis. KIT and PDGFRA are transmembrane glycoproteins that are a part of the type 3 receptor tyrosine kinase family [10] and map to chromosome 4q12 [30]. The distinctive molecular structure of this protein family consists of an extracellular domain with 5 immunoglobulin-like loops, which are critical for the binding of ligand and dimerization; and a cytoplasmic domain with tyrosine kinase domain [31]. Mutations of KIT and PDGFRA in GISTs are mutually exclusive. Various mutations in KIT and PDGFRA, including point mutations, deletions, duplications, and insertions have all been reported [10]. KIT is frequently mutated in exon 2, exon 8, exon 9, exon 11, exon 16, and exon 17, whereas PDGFRA mutations are located in exon 12, exon 14 and exon 18 [32]. More than 95% of PDGFRA mutations are found in the stomach, mesentery, or omentum region, while the site of origin for the KIT mutant GISTs is the small intestine [33]. D842V in exon 18 is the most common mutant that accounts for 62.6% of PDGFRA-associated GISTs [33]. The mutations in exon 11 of KIT induces conformational changes that distort the autoinhibitory domain of the protein and thereby activating its kinase function continuously [34]. Likewise, mutations in exon 9 located in the extracellular region induces repeated dimerization and constitutive activation of KIT thereby inducing tumorigenesis.

SDH Mutation in GIST

Among the GISTs, SDH mutation is unique with the defect in the energy metabolism [35]. It is different from other GISTs in terms of its morphological, clinical, and molecular characteristics. The SDH protein consists of 4 different subunits namely, SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD. In mitochondria, it plays a pivotal role in the Krebs cycle and electron transport chain. The enzymatic activity is controlled by SDHA (catalytic core) and SDHB (iron sulphur protein), whereas anchorage of this complex with the inner membrane of mitochondria is facilitated by SDHC and SDHD subunits [36]. Among all the SDH mutations in GISTs, 30% is contributed by the SDHA subunit [37]. The mutation SDH is mostly germline with allelic loss at chromosome 5p15 and translates to protein revoke in R31X [26]. SDH-mutated GISTs have the female predilection and lack mutations in the proto-oncogene KIT or PDGFR. The mutation of the SDH subunits causes the accumulation of oncometabolite succinate, which completely disrupts the oxygen-dependent signaling in the GIST microenvironment [38]. In hypoxic conditions of the tumor microenvironment, prolyl hydroxylase fails to target HIF1α for proteasome-mediated degradation. This causes the accumulation of HIF1α that translocates into the nucleus to increase the transcriptional level of several genes such as IGF1, IGF2, and VEGF thereby inducing tumorigenesis [39]. Till date, surgical management is the major line of therapy for SDH-mutated GISTs as they do not respond well to the tyrosine kinase inhibitors including imatinib and sunitinib.

Non SDH Mutations

The non-SDH-deficient GISTs arise due to mutation in BRAF, KRAS, PIK3CA, and NF1 genes. Mutations of these genes activate the signalling cascade through the upregulation of MEK and ERK which enhances cellular proliferation. The BRAF gene, which is mutated in most of the malignancies, is a serine/threonine protein kinase that regulates proliferation and differentiation through the Ras-Raf-MAPK kinase pathway. In kinase panel screening, it was found that the ATP-competitive inhibitor of BRAF kinase namely, dabrafenib is highly selective for mutant BRAF. Dabrafenib has demonstrated excellent anticancer effects for V600E BRAF-mutated GISTs. BRAF mutations are present in roughly 13% of KIT and PDGFRA wild-type GISTs. Higher oncogenic signaling through both the PI3K/mTOR and RAS/MAPK pathways is observed in non-SDSH mutant GISTs. PI3K and/or RAS pathway-activating mutations promote KIT independence and increase TKI resistance in GISTs. Co-inhibition approaches of RAS and PI3K pathways along with oncogenic KIT/PDGFRA signaling cascade would effectively target advanced GIST and require further research.

FGF/FGFR family in GIST

FGFR is a tyrosine kinase transmembrane receptor that belongs to the immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily. In humans, there are four members in the FGFR family namely, FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, and FGFR4. The members of the FGFR family have a highly conserved amino acid sequence with variations in the extent of ligand binding and tissue distribution [40]. The FGFR family is also composed of FGFR5 or FGFRL1 which lacks tyrosine kinase activity [41]. The negative regulation of the FGFR signaling pathway by FGFRL1 leads to the inhibition in differentiation and cellular proliferation [41]. The structure of FGFR comprises an extracellular ligand binding domain, two domains of tyrosine kinase in the intracellular region, and a transmembrane helix [40]. In the extracellular portion, there are three Ig domains associated with the linker region with a highly conserved region of aspartate, serine, and glutamate-rich sequence located in between the first and second loop of Ig, commonly known as acid box [40,42]. The first Ig loop and acid box facilitate autoinhibition of the receptor, while the second and third loops of Ig facilitate the binding of FGF and determine the specificity of ligand binding [40,42]. The native ligand of FGFs receptor belongs to 22 families based on their evolutionary relation and homology sequence. The secreted FGFs belong to the subfamily such as FGF1, FGF4, FGF7, FGF8, and FGF9 and exhibit typical functions like cellular proliferation, survival and differentiation, through signaling of FGFRs [43]. The dimerization process during the binding of FGF ligands results in the conformational shift which induces the autophosphorylation of FGFR in the intracellular kinase domain leading to the downstream signaling pathways [44]. FGFR substrate 2, an adaptor protein has a large contribution to FGFR in phosphorylation which recruits some other adaptor proteins (SOS, GRB2) that result in activating RAS and regulating the downstream RAF/MAPK pathway involved in cellular proliferation [43,45]. GRB2 can also bind GAB1 and promotes cellular survival by promoting the PI3K/AKT pathway. The phosphorylation by the activated FGFR tyrosine kinase induces phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ) and the signal transducers and activator of the transcription (STAT) pathway. The enhancement of FGF signals due to activated missense FGFR1 mutation (p.K656E) and two gene fusions namely, FGFR1–HOOK3 (in-frame fusion of HOOK3 intron-4 and FGFR1 intron 17) and FGFR1–TACC1 (in-frame fusion of TACC1 intron-6 and FGFR1 intron 17) triggers the qWT GISTs [46].

Under Expression of Tumor Suppressor Genes

Neurofibromatosis type 1 is an autosomal dominant disease that arises due to the biallelic loss or mutation in the tumor suppressor NF1 gene. An increasing body of research has suggested a link between NF1 and GIST. Previously, NF1-associated GIST with different molecular etiology has been reported [47]. The GAP-related domain associated with the NF causes the transformation of inactive Ras-GDP from active Ras-GDP resulting in the downregulation of the RAS signaling pathway. NF1 mutation results in a high risk of GISTs in the individuals which was characterized by small size, multiplicity factor and location [48]. Majorly, NFI associated GISTs are characterized as CD117 which is a selective marker for the GISTs. It exhibits the hyperplastic foci of CD117 which is the precursor for the GISTs and also the precursor for the NF-1 associated GISTs. All the mutant gene leads to the alteration in the KIT/PDGFRA signaling pathway, whereas the NF1 mutation causes the activation of the MAPK signaling pathway [49].

Dystrophin is an important protein involved in the strengthening of muscles and is also associated with GISTs. Active dystrophin demonstrates tumor suppressor role in the ICCs by inhibiting cell invasion, independent anchorage, and diffusion by forming invadopodia. The intragenic deletion of dystrophin was reported to induce GISTs [50]. Tumor P53 or TP53 is a tumor suppressor protein by regulating cell division, mediate DNA repair, cell cycle arrest, and cell death. Normally, P53 has a very short half-life and is present at a low level. The mutated TP53 is differentiated from the normal P53 as it leads to the degradation of proteasomal and ubiquitination [51]. The negative regulation of P53 is done by the Murine double-minute 2, E3 ubiquitin ligase results in the degradation and ubiquitination. In the wild type of TP53, the effect of P53 inhibited by MDM2 is low suggesting that the alteration in the P53 is used as the therapeutic approach for GISTs [52]. In addition to the mutation, epigenetic mechanisms play an important role in the formation of tumors. The epigenetic mechanisms include deacetylation of histone, genomic heterochromatinization, and genomic imprinting loss [53]. Promoter hypermethylation causes the silencing of tumor suppressor genes at the CGIs region is common in GISTs. The hypermethylation causes loss of transcription in many tumor suppressor genes such as E-cadherin, p16/ INK4a, hMLH1, p15/INK4b, and VHL [54].

Aberrations in DNA Damage Repair Pathways

DNA damaging agents such as ionizing radiation, chemotherapeutic agents, and UV light result in DNA abrasion, including breaks in the single or double strands, modification in sugar bases, and cross-linking of the strands. Maintenance of DNA integrity is very critical for normal cellular function and its damage is a key hallmark in the malignant transformation if not repaired [55]. To prevent the accumulation of DNA damage DNA, cells enable a series of processes known as DNA damage response (DDR) [56]. The heterozygous deletion (HelDels) of DNA damage-sensing genes such as CHEK2, BRCA2, and RB1 results in the aberrations of DDR. Furthermore, using next-generation sequencing HelDels in RB1, along with genes involved in HRR (RAD51) and Fanconi anemia (BRCA2) pathways are reported in GISTs [57]. BRCA is a key player in DNA repair by homologous recombinant. The cells with mutant BRCA result in Homologous recombination deficiency (HRD). The functions of BRCA genes are recognition of DNA damage, repairing double-strand breaks, control of checkpoint in the cell cycle, regulation of transcription, and remodeling of chromatin. These functions show the importance of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation in the formation of malignancies [58]. However, the relation between the deficiencies in the BRCA and the formation of tumors in GITs is unclear.

Conclusion

The management of GISTs has advanced expeditiously during the past two decades due to the ever-widening understanding of the tumor molecular diversity. The majority of GIST are associated with the activating mutation in the KIT/PDGFRA kinases. Approval of imatinib, sunitinib, and regorafenib as first, second, and third-line of therapy respectively for the inhibition of KIT/PDGFRA kinases has significantly improved the treatment of GISTs. However, a major drawback of these 3 approved drugs is that they target the inactive conformation of the and hence their efficacy is suppressed due to the secondary mutations that develop in the activation loop of KIT/PDGFRA. Moreover, there are significant unmet needs for the subset of patients with KIT/PDGFRA-wild type GISTs such as SDH-deficient GIST, NF1-mutant RAS-mutant, BRAF mutant, FGFR mutant GISTs, and others. These categories of patients shall be considered distinctly, and their therapy shall be focused on the mutational status and potential molecular vulnerabilities. In the future, the clinical trial development shall be predominantly molecularly focused, which would specifically target each subset of the GISTs.

Abbreviations

GISTs: Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors; PDGFRA: Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Alpha; MAPK: Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase; RAF: Rapidly Accelerated Fibrosarcoma; WT: Wild Type; KIT: Receptor tyrosine kinase; SDH: Succinate Dehydrogenase; NTRK: Neurotrophic Tyrosine Receptor Kinase; FGF: Fibroblast Growth Factor; HIF: Hypoxia-Inducible Factors; IGF: Insulin-like Growth Factor; VEGF: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor; MEK: Mitogen-activated protein kinase Kinase; ERK: Extracellular signal-Regulated Kinase; SOS: Son of Sevenless; GRB2: Growth factor Receptor-Bound protein 2; GAB1: GRB2-Associated-Binding protein 1; PLCγ: Phospholipase C, gamma; FGFR: Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor; HOOK3: Hook Microtubule Tethering Protein 3; TACC1: Transforming Acidic Coiled-Coil Containing Protein 1; VHL: Von Hippel–Lindau syndrome; HRR: Homologous Recombination Repair; HRD: Homologous Recombination Deficiency.

Acknowledgment

We cordially thank the Indian Institute of Information Technology, Design and Manufacturing – kancheepuram for providing the necessary infrastructure to carry out this work successfully.

References

2. Sbaraglia M, Businello G, Bellan E, Fassan M, Dei Tos AP. Mesenchymal tumours of the gastrointestinal tract. Pathologica. 2021;113:230-251.

3. Jumniensuk C, Charoenpitakchai M. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor:clinicopathological characteristics and pathologic prognostic analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16:231.

4. Wang Q, Huang Z-P, Zhu Y, Fu F, Tian L. Contribution of Interstitial Cells of Cajal to Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor Risk. Med Sci Monit. 2021;27:e929575.

5. Bauer S, George S, von Mehren M, Heinrich MC. Early and Next-Generation KIT/PDGFRA Kinase Inhibitors and the Future of Treatment for Advanced Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor. Front Oncol. 2021;11:672500.

6. Bauer S, Duensing A, Demetri GD, Fletcher JA. KIT oncogenic signaling mechanisms in imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumor:PI3-kinase/AKT is a crucial survival pathway. Oncogene. 2007;26:7560-7568.

7. Bosbach B, Rossi F, Yozgat Y, Loo J, Zhang JQ, Berrozpe G, et al. Direct engagement of the PI3K pathway by mutant KIT dominates oncogenic signaling in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E8448-E8457.

8. Liang J, Wu Y-L, Chen B-J, Zhang W, Tanaka Y, Sugiyama H. The C-kit receptor-mediated signal transduction and tumor-related diseases. Int J Biol Sci. 2013;9:435-443.

9. Indio V, Ravegnini G, Astolfi A, Urbini M, Saponara M, De Leo A, et al. Gene Expression Profiling of PDGFRA Mutant GIST Reveals Immune Signatures as a Specific Fingerprint of D842V Exon 18 Mutation. Front Immunol. 2020;11:851.

10. Rubin BP, Heinrich MC. Genotyping and immunohistochemistry of gastrointestinal stromal tumors:An update. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2015;32:392-399.

11. Nannini M, Biasco G, Astolfi A, Pantaleo MA. An overview on molecular biology of KIT/PDGFRA wild type (WT) gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST). J Med Genet. 2013;50:653-661.

12. Miettinen M, Wang Z-F, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Osuch C, Rutkowski P, Lasota J. Succinate dehydrogenase-deficient GISTs:a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 66 gastric GISTs with predilection to young age. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1712-1721.

13. Killian JK, Kim SY, Miettinen M, Smith C, Merino M, Tsokos M, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase mutation underlies global epigenomic divergence in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:648-657.

14. Xu Z, Huo X, Tang C, Ye H, Nandakumar V, Lou F, et al. Frequent KIT mutations in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5907.

15. Oppelt PJ, Hirbe AC, Van Tine BA. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs):point mutations matter in management, a review. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;8:466-473.

16. Choi H-J, Jin S, Cho H, Won H-Y, An HW, Jeong G-Y, et al. CDK12 drives breast tumor initiation and trastuzumab resistance via WNT and IRS1-ErbB-PI3K signaling. EMBO Rep. 2019;20:e48058.

17. Haines E, Saucier C, Claing A. The adaptor proteins p66Shc and Grb2 regulate the activation of the GTPases ARF1 and ARF6 in invasive breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:5687-5703.

18. Feng Y, Yao S, Pu Z, Cheng H, Fei B, Zou J, et al. Identification of New Tumor-Related Gene Mutations in Chinese Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;0. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.764275

19. Tornillo L, Terracciano LM. An update on molecular genetics of gastrointestinal stromal tumours. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:557-563.

20. Wang S, Zhang Q, Wu H, Yang Z, Guo X, Wang F, et al. Mutations of the and gene in gastrointestinal stromal tumors among hakka population of Southern China. Niger J Clin Pract. 2021;24:814-820.

21. Miettinen M, Killian JK, Wang Z-F, Lasota J, Lau C, Jones L, et al. Immunohistochemical loss of succinate dehydrogenase subunit A (SDHA) in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) signals SDHA germline mutation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:234-240.

22. Dwight T, Benn DE, Clarkson A, Vilain R, Lipton L, Robinson BG, et al. Loss of SDHA expression identifies SDHA mutations in succinate dehydrogenase-deficient gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:226-233.

23. Pantaleo MA, Astolfi A, Urbini M, Nannini M, Paterini P, Indio V, et al. Analysis of all subunits, SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD, of the succinate dehydrogenase complex in KIT/PDGFRA wild-type GIST. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:32-39.

24. Wagner AJ, Remillard SP, Zhang Y-X, Doyle LA, George S, Hornick JL. Loss of expression of SDHA predicts SDHA mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:289-294.

25. Pantaleo MA, Astolfi A, Indio V, Moore R, Thiessen N, Heinrich MC, et al. SDHA loss-of-function mutations in KIT-PDGFRA wild-type gastrointestinal stromal tumors identified by massively parallel sequencing. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:983-987.

26. Janeway KA, Kim SY, Lodish M, Nosé V, Rustin P, Gaal J, et al. Defects in succinate dehydrogenase in gastrointestinal stromal tumors lacking KIT and PDGFRA mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:314-318.

27. Oudijk L, Gaal J, Korpershoek E, van Nederveen FH, Kelly L, Schiavon G, et al. SDHA mutations in adult and pediatric wild-type gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:456-463.

28. Astolfi A, Pantaleo MA, Indio V, Urbini M, Nannini M. The Emerging Role of the FGF/FGFR Pathway in Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21. doi:10.3390/ijms21093313

29. Fletcher JA. KIT Oncogenic Mutations:Biologic Insights, Therapeutic Advances, and Future Directions. Cancer Res. 2016;76:6140-6142.

30. Lasota J, Miettinen M. KIT and PDGFRA mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). Semin Diagn Pathol. 2006;23:91-102.

31. Mayr P, Märkl B, Agaimy A, Kriening B, Dintner S, Schenkirsch G, et al. Malignancies associated with GIST:a retrospective study with molecular analysis of KIT and PDGFRA. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2019;404:605-613.

32. Lasota J, Miettinen M. Clinical significance of oncogenic KIT and PDGFRA mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Histopathology. 2008;53:245-266.

33. Martín-Broto J, Rubio L, Alemany R, López-Guerrero JA. Clinical implications of KIT and PDGFRA genotyping in GIST. Clin Transl Oncol. 2010;12:670-676.

34. Corless CL, Schroeder A, Griffith D, Town A, McGreevey L, Harrell P, et al. PDGFRA mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors:frequency, spectrum and in vitro sensitivity to imatinib. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5357-5364.

35. Gajiwala KS, Wu JC, Christensen J, Deshmukh GD, Diehl W, DiNitto JP, et al. KIT kinase mutants show unique mechanisms of drug resistance to imatinib and sunitinib in gastrointestinal stromal tumor patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1542-1547.

36. Kosmider O, Gelsi-Boyer V, Slama L, Dreyfus F, Beyne-Rauzy O, Quesnel B, et al. Mutations of IDH1 and IDH2 genes in early and accelerated phases of myelodysplastic syndromes and MDS/myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2010;24:1094-1096.

37. Wang Y-M, Gu M-L, Ji F. Succinate dehydrogenase-deficient gastrointestinal stromal tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:2303-2314.

38. Boikos SA, Pappo AS, Killian JK, LaQuaglia MP, Weldon CB, George S, et al. Molecular Subtypes of KIT/PDGFRA Wild-Type Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors:A Report From the National Institutes of Health Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor Clinic. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:922-928.

39. Iommarini L, Porcelli AM, Gasparre G, Kurelac I. Non-Canonical Mechanisms Regulating Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 Alpha in Cancer. Front Oncol. 2017;7:286.

40. Ruas JL, Poellinger L. Hypoxia-dependent activation of HIF into a transcriptional regulator. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:514-522.

41. Itoh N, Ornitz DM. Evolution of the Fgf and Fgfr gene families. Trends Genet. 2004;20:563-569.

42. Trueb B. Biology of FGFRL1, the fifth fibroblast growth factor receptor. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:951-964.

43. Kalinina J, Dutta K, Ilghari D, Beenken A, Goetz R, Eliseenkova AV, et al. The alternatively spliced acid box region plays a key role in FGF receptor autoinhibition. Structure. 2012;20:77-88.

44. Turner N, Grose R. Fibroblast growth factor signalling:from development to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:116-129.

45. Ornitz DM, Itoh N. The Fibroblast Growth Factor signaling pathway. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2015;4:215-266.

46. Brewer JR, Mazot P, Soriano P. Genetic insights into the mechanisms of Fgf signaling. Genes Dev. 2016;30:751-771.

47. Shi E, Chmielecki J, Tang C-M, Wang K, Heinrich MC, Kang G, et al. FGFR1 and NTRK3 actionable alterations in “Wild-Type” gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Transl Med. 2016;14:339.

48. Bharath BG, Rastogi S, Ahmed S, Barwad A. Challenges in the management of metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1:a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2022. doi:10.1186/s13256-022-03382-y

49. Miettinen M, Fetsch JF, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis 1:a clinicopathologic and molecular genetic study of 45 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:90-96.

50. Maertens O, Prenen H, Debiec-Rychter M, Wozniak A, Sciot R, Pauwels P, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors in NF1 patients. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1015-1023.

51. Wang Y, Marino-Enriquez A, Bennett RR, Zhu M, Shen Y, Eilers G, et al. Dystrophin is a tumor suppressor in human cancers with myogenic programs. Nat Genet. 2014;46:601-606.

52. Bang S, Kaur S, Kurokawa M. Regulation of the p53 Family Proteins by the Ubiquitin Proteasomal Pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;21. doi:10.3390/ijms21010261

53. Henze J, Mühlenberg T, Simon S, Grabellus F, Rubin B, Taeger G, et al. p53 modulation as a therapeutic strategy in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37776.

54. House MG, Guo M, Efron DT, Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Syphard JE, et al. Tumor suppressor gene hypermethylation as a predictor of gastric stromal tumor behavior. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:1004-14; discussion 1014.

55. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer:the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646-674.

56. Giglia-Mari G, Zotter A, Vermeulen W. DNA damage response. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a000745.

57. Liu T-T, Li C-F, Tan K-T, Jan Y-H, Lee P-H, Huang C-H, et al. Characterization of Aberrations in DNA Damage Repair Pathways in Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors:The Clinicopathologic Relevance of γH2AX and 53BP1 in Correlation with Heterozygous Deletions. Cancers . 2022;14.

58. Waisbren J, Uthe R, Siziopikou K, Kaklamani V. BRCA 1/2 gene mutation and gastrointestinal stromal tumours:a potential association. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015.