Abstract

Rhabdomyosarcoma, a malignant tumor commonly found in children and adolescents, often carries a poor prognosis. We conducted studies on the effects of the liposoluble extract of Nicotiana glauca (N. glauca), a plant from the Solanaceae family that is widely distributed, on the C2C12 murine myoblast cell line. We additionally investigated the antiproliferative effects of the extract on the RD rhabdomyosarcoma tumor cell line. The RD cells were pre-incubated without fetal bovine serum, followed by treatment with the liposoluble extract and the n-hexane sub-extract at specific concentrations. The effects on cell morphology were assessed using staining techniques. Cell viability, growth, and division capacities were evaluated through a wound assay. We analyzed the expression levels and subcellular localization of several proteins, including β-catenin, Notch 1, Caspase 3, and 14-3-3, using Western blotting. The extract of N. glauca induces apoptosis in C2C12 cells, suggesting that it may possess antitumor properties and could potentially be used in the treatment of hyperproliferative disorders. Our findings revealed that the control cells exhibited intact and normal nuclei, while the treated cells displayed characteristic morphological changes associated with apoptosis. Also, the treatments significantly reduced cell division capacity, and potentially cell migration, compared to the control group. Moreover, the evaluation of β-catenin protein localization showed a cytoplasmic and membrane proximity in C2C12 cells, whereas RD cells exhibited nuclear localization. These findings suggest the potential therapeutic value of the extract in targeting the proliferation and spread of rhabdomyosarcoma cells.

Keywords

Apoptosis, Rhabdomyosarcoma cells, Extracts of N. glauca

Introduction

Cancer is a leading cause of childhood mortality, with rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) being the most prevalent type diagnosed in approximately two-thirds of pediatric cancer cases, particularly the embryonal subtype. RMS represents the most common soft tissue sarcoma in children and adolescents, accounting for around 2-3.5% of all pediatric malignancies [1]. The incidence of RMS is approximately four new cases per million children under the age of 20, and it is observed worldwide without a specific geographical predilection [2]. However, studies suggest a higher incidence among white individuals compared to black individuals [2]. RMS is characterized by its primitive mesenchymal origin and a propensity for differentiation into striated muscle tissue. While it can manifest in various anatomical sites, the extremities are the most common location in adults, followed by the trunk, genitourinary tract, head, and neck [3].

Histologically, RMS is classified into two subtypes: embryonal (eRMS) and alveolar (aRMS). eRMS is more prevalent in childhood and is commonly found in sites such as the orbit, head, neck, and genitourinary tract [2]. Recent studies have also reported a predilection for the upper and lower extremities [4]. On the other hand, aRMS constitute 20-25% of RMS diagnoses and is characterized by smaller, rounder cells resembling pulmonary alveoli. This subtype is more frequent in older children and displays a more aggressive behavior. Other less common variants of RMS include pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma (pRMS), which predominantly affects individuals older than 25 years and is associated with an unfavorable prognosis like aRMS; undifferentiated sarcomas, which comprise 11% of RMS cases and have a poor prognosis; and unclassifiable sarcomas, accounting for 5-10% of pediatric cases, which cannot be categorized due to the lack of defining characteristics and typically have a worse prognosis. In terms of immunochemical features, eRMS cells exhibit nuclear localization of β-catenin in addition to the typical cytosolic and proximal membrane localization. They also express high levels of N-cadherin and integrin α-9, both of which are positively regulated by Notch pathway. These molecular characteristics enhance cell mobility, invasiveness, aggressiveness, and the maintenance of an undifferentiated state within the tumor [5]. Cancer cells gradually acquire distinct biological capabilities, referred to as "hallmarks," enabling tumor establishment and progression [6,7]. These hallmarks include the activation and maintenance of proliferative signals, evasion of growth suppressive signals, resistance to cell death, replicative immortality, induction of angiogenesis, activation of invasion mechanisms and metastasis (such as aberrant Wnt-β-catenin signaling with low E-cadherin levels and nuclear localization of β-catenin), reprogramming of energy metabolism to support continuous cell proliferation, and evasion of immune system surveillance. Genomic instability and mutations in neoplastic cells are key facilitators of cancer hallmark acquisition, generating genetic variations responsible for these distinct capabilities. Inflammation, which contributes bioactive molecules to the tumor microenvironment, is another facilitating characteristic of tumor development [7].

Apoptosis, an active process in normal skeletal muscle during intense exercise or in pathologies such as muscular dystrophy, muscle denervation, myopathies, and sarcopenia, is of interest in RMS research. These conditions are often associated with the accumulation of defective mitochondria [8] or reduced oxidative capacity due to mitochondrial dysfunction [9]. Our previous studies demonstrated that C2C12 myoblasts share similarities with activated satellite cells surrounding mature myofibers, as they proliferate and differentiate, participating in tissue repair during cellular injury. We also identified hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as an inducer of apoptosis in C2C12 cell line, observing characteristic morphological changes. Additionally, we investigated the apoptotic pathway components activated during apoptosis, including proteins, transcription factors, and regulated genes. We observed a reduction of these effects upon treatment with 17β-estradiol (E2) or testosterone, suggesting their potential protective roles [10-16]. Furthermore, we found that the liposoluble extract of Nicotiana glauca (N. glauca) induces apoptosis in C2C12 cells, involving caspase activation and the regulation of pro- and anti-apoptotic protein gene expression. In contrast, the aqueous extract of N. glauca had no effect on the cells [17]. In this study, we aim to further investigate the effects of N. glauca extracts on RD cells, including viability, replication, migration, and the expression and subcellular localization of key proteins involved in invasion, metastasis, and apoptosis pathways.

Materials and Methods

Materials

MitoTracker (MitoTracker ® Red CMXRos) was from Sigma Aldrich, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). Anti-Lamin B (B-10): sc-374015, anti β-catenin (H-1): SC-133240, anti-caspase 3, and anti-Notch 1 (mN1A): sc-32745 antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). All other reagents used were of analytical grade.

Cell culture

C2C12 (ATCC number: CRL-1772™) mouse myoblast cell line and human rhabdomyosarcoma RD cell line (ATCC number: CCL-136TM) were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2 and passaged were performed every 48 to 72 hours using fresh medium.

Nicotiana glauca extracts

N. glauca plants specimens were collected from their natural habitats in Buenos Aires Province, Argentina and were grown under greenhouse conditions. An herbarium voucher specimen has been kept at the Herbarium of the Department of Agronomy Universidad Nacional del Sur from N. glauca leaves, the liposoluble (crude) and n-hexane sub - extracts were obtained. The liposoluble extract was isolated following the Bligh & Dyer method [20]. The starting plant material was initially homogenized in chloroform - methanol (1:2, v/v) using a refrigerated Sorvall centrifuge at 8°C at maximum speed for 2 minutes. The samples were further homogenized after the addition of chloroform (1.2 ml/g of tissue) for 30 seconds and then after the addition of distilled water (1.2 ml/g) for another 30 seconds. The final homogenate was centrifuged at 4300 x g for 20 minutes. The lower liposoluble phase was collected and evaporated by flushing nitrogen at 35°C. The final residue was solubilized in isopropanol. The concentrated liposoluble extract (not lyophilized) was partitioned into three sub-extracts: n-hexane, chloroform, and ethyl acetate. Among these three sub extracts, the n-hexane sub extract had the highest apoptotic effect in muscle cells, determined in cell cultures using the TUNEL assay and based on the changes induced in cell morphology, visualized by the staining with DAPI and MitoTracker red (MTT) [17]. The extracted solutions were evaporated under reduced pressure and then lyophilized.

Extract preparation

The extract, 0.1 mg dry powder, was resuspended in 500 μl of isopropanol (stock). Dilution preparation: 1 μl of the stock was resuspended in 1000 μl of serum-free DMEM (1:1000) and from this first dilution the final dilution was prepared: 1:1000 in serum-free DMEM medium [17,18]. At this concentration, it was proved that the n-hexane sub extract induces a 70% of apoptosis [19].

Cells treatments

The treatments were performed with 70-80% confluents cultures in medium without serum for 20 minutes. Then, treatments were carried out by adding the liposoluble and n-hexane extract of N. glauca or the vehicle, isopropanol (IPA) (the IPA percentage in the culture medium assay, of the cells treated with extracts or the vehicle alone, was less than 0.001%) during 1 or 2 hours at 37°C in a humid atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. Cells were cultured in 3 cm and 6 cm sterile plates (Greiner Bio-One, Frankenhauser, Germany).

MitoTracker red (MTT) and DAPI staining

After treatment, the cells attached to the coverslips were stained with MTT, which was prepared on dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and added to the cell culture medium at a final concentration of 1 µmol/L (1:10000, prepared in DMEM without FBS). After 30 minutes incubation at 37°C, the cells were washed with PBS 1X (pH 7.4, 8 g/L NaCl, 0.2 g/l KCl, 0.24 g/L KH2PO4, 1.44 g/L Na2HPO4) and they were fixed with methanol at -20°C for 30 minutes. Cells were washed 3 more times with PBS 1X to ensure that any methanol residue had been removed. The cells were later stained with DAPI (1:500 dilution from a stock solution of 5 mg/ml). This was incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature in darkness and gentle stirring. The cells were then washed 3 times with PBS after the incubation time, and the samples were prepared for viewing under the microscope. The cells were examined using a fluorescence microscope (NIKON Eclipse TiS) equipped with standard filter sets to capture fluorescent signals. Images were collected using a digital camera.

Wound scratch assay

Cells were seeded in dishes and cultured until reaching 80-90% confluence. The treatments with N. glauca extracts were performed, and after the specified time, a cross-shaped wound was made on the cell monolayer. The medium was changed to fresh medium, and the wound closure was monitored for 24 hours or until complete closure. Images were taken at regular intervals using a digital camera coupled to an optical microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti-S).

Immunocytochemistry

After treatments, semi-confluent (70-80%) monolayers were washed with serum-free phenol red-free DMEM and then fixed and permeabilized for 20 minutes at -20°C with methanol to allow intracellular antigen labeling. After fixation, cells were rinsed 3 times with PBS. Non-specific sites were blocked for 30 minutes in PBS that contained 5% bovine serum albumin. Cells were then incubated overnight at 4°C, in the presence or absence (negative control) of primary antibodies (1:50 dilution). The primary antibodies were recognized by fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies. Finally, the coverslips were analyzed by conventional fluorescence microscopy.

Subcellular fractionation

RD monolayers were scrapped and homogenized in ice cold Tris - EDTA - sucrose (TES) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCL (pH 7,4), 1 nM EDTA, 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM DTT, 0,5 mM PMSF, 20 mg/ml leupeptin, 20 mg/ml aprotinin, 20 mg/ml trypsin inhibitor) using a Teflon - glass hand homogenizer. Total homogenate was centrifuged at 100 x g for 5 min at 4°C to eliminate the unbroken cells, partially disrupted cell, and other debris. Then, total homogenate free of debris was used to obtain the different fractions (nuclear, mitochondrial, and mitochondrial supernatant). The nuclear pellet was obtained by centrifugation at 300 x g during 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was further centrifuged at 10000 x g for 30 min at 4°C to yield the mitochondria pellet. The remaining solution was called mitochondrial supernatant. Pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCL, pH 7,4, 150 mM NaCl, 0,2 mM Na2VO4, 2 mM EDTA, 25 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, 20 mg/ml leupeptin, and 20 mg/ml aprotinin). Protein concentration of the fractions was estimated by the method of Bradford [21] and Western blot assays were performed. Cross contamination between fractions was assessed by immunoblots using antibodies against anti - Lamin B as nuclear markers.

Western blot analysis

Protein aliquots (25 μg) were combined with sample buffer (400 mM Tris-HCL (pH 6.8), 10% SDS, 50% glycerol, 500 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 2 mg/ml Bromophenol Blue, boiled for 5 min and resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE according to the method of Laemmli [22]. Fractionated proteins were then electrophoretically transferred onto Polyvinylidene Difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Immobilon-P; Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), using a semi-dry system. The nonspecific sites were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (PBS-T). Blots were incubated overnight with the appropriate dilution of the specific primary antibodies against the proteins studied. The membranes were repeatedly washed with PBS-T prior to incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. The enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) blot detection kit (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, England) was used as described by the manufacturer to visualize reactive products. Relative quantification of Western blot signals was performed using ImageJ Software (NIH, USA).

Statistical analysis

Results are shown as means ± S.E.M. Statistical differences among groups were determined by ANOVA followed by a multiple comparison post hoc test, the Di Rienzo, Guzma´n Casanove´s (DGC) test [23]. Data are expressed as significant at P<0.05.

Results

The liposoluble extract of N. glauca induced morphological changes typical of apoptosis in RD cells

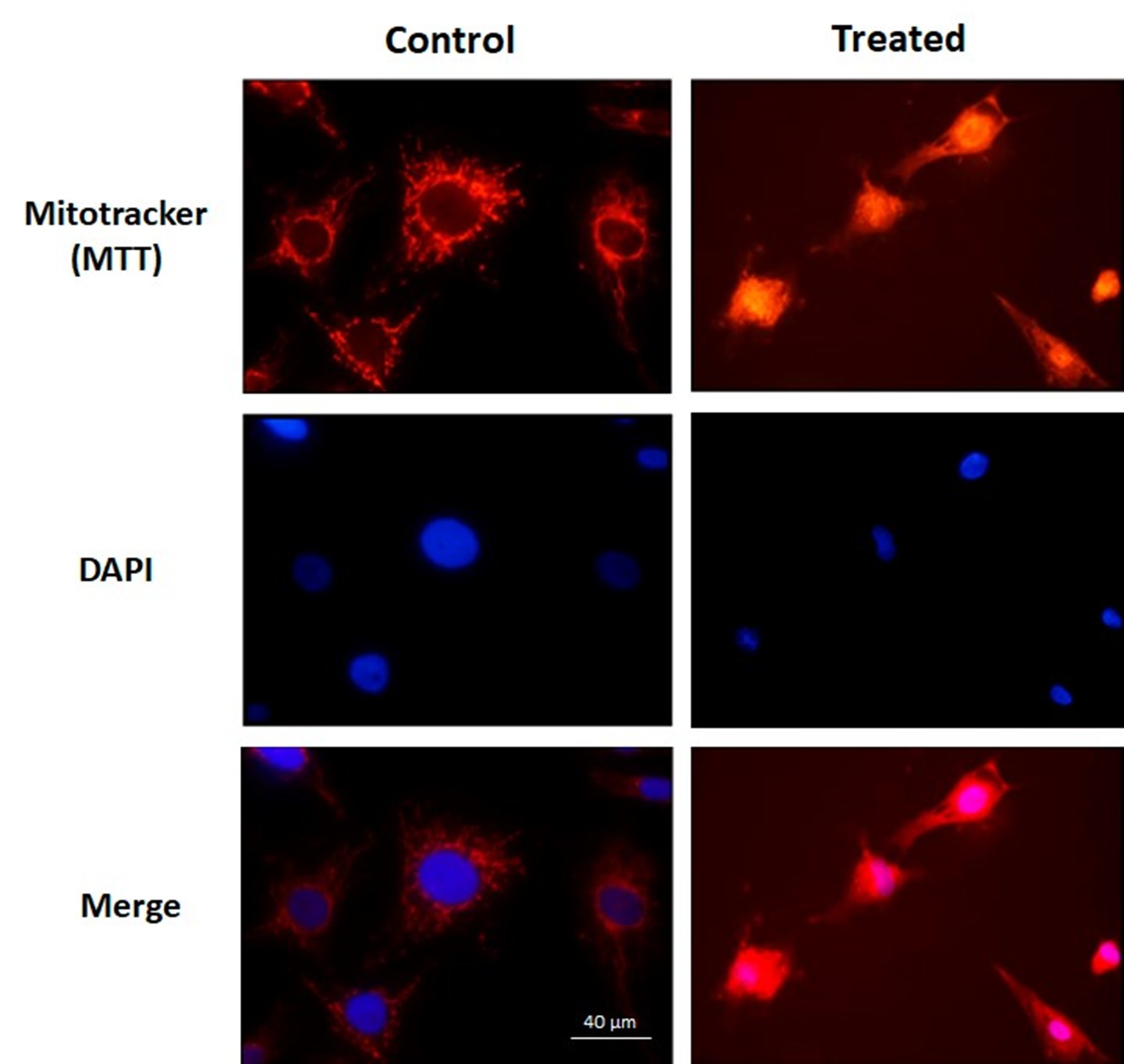

As a first approach to investigate the effects of the N. glauca extract on the apoptosis of RD cells, mitochondrial and nuclear morphology were studied by immunocytochemistry assays and immunofluorescence conventional microscopy using Mitotracker and DAPI dyes, which were performed after treatment. It was observed that the liposoluble extract of N. glauca induced apoptosis on RD cell line, as evidenced by changes in nuclear and mitochondrial morphology. Under control conditions, muscle cells exhibited intact/normal nuclei and a "spider web" distribution of mitochondria. However, treatment with the liposoluble extract replicated the characteristic morphological alterations observed in apoptotic cells, including nuclear condensation and loss of the typical mitochondrial distribution (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The liposoluble extract of N. glauca induces apoptosis in RD cells. Cell cultures were treated with the liposoluble extract of N. glauca for 2 h (Treated) or maintained in DMEM without serum for 2 h (Control). Cells were then stained with MTT Red (red) and subsequently fixed and stained with DAPI (blue), as described in the Methods section. Morphological analysis of fluorescence-stained nuclei and percentages of apoptotic cells at each condition are shown. At least ten fields per dish were examined. Each value represents the mean of three independent experiments. Averages ± S.E.M. are given; *P <0.05 with respect to the control. Magnification: 63X.

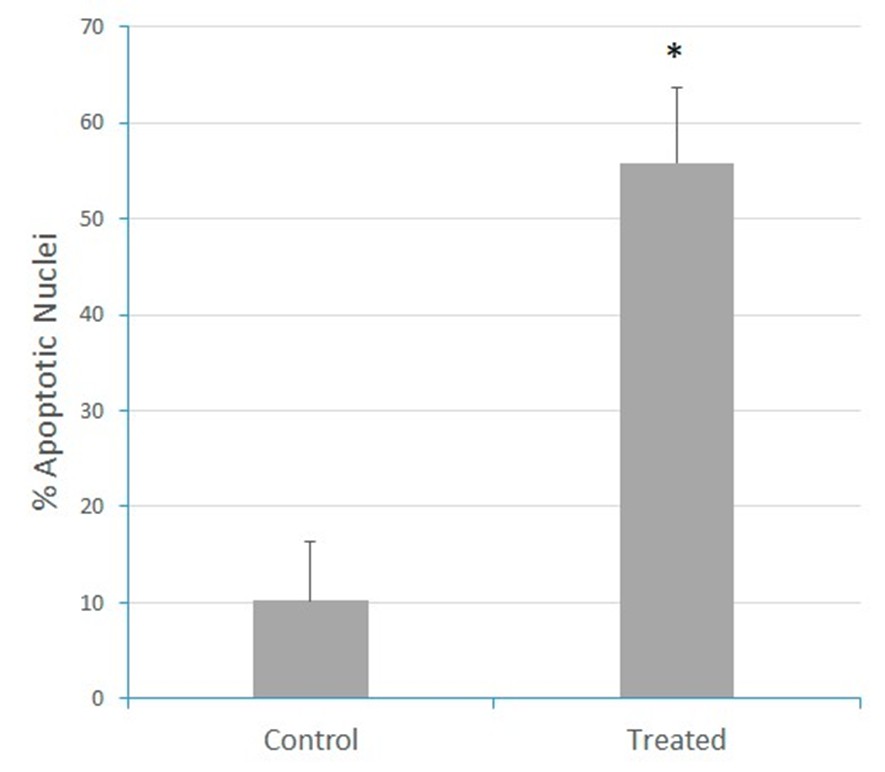

Extracts from N. glauca affected the cell cycle by reducing the rate of cell division and potentially also influencing cell migration

The effects of the extracts of N. glauca on the cell cycle and cell migration were then analyzed. After reaching 100% confluence, RD cells were treated for 1 hour with either n-hexane or the liposoluble extract. A cross-shaped wound was then created, and the closure of the central area of the wound was monitored every 20 minutes under a light microscope. Figure 2 shows the images captured at zero hours (after creating the wound and replacing the medium with serum-containing culture medium, 0% of wound occupancy) and at 24 hours (end of the assay). The treatment with the liposoluble extract and the n-hexane sub-extract significantly inhibited the division capacity and likely reduced cell migration (3% and 1% of wound occupancy, respectively) compared to the control, where complete wound closure was observed 24 hours after the start of the assay (95% of wound occupancy) (Figure 2). These findings indicate that N. glauca extracts also impact the cell cycle, resulting in a reduced rate of cell division and potentially affecting cell migration.

Figure 2: Extracts from N. glauca affect the cell cycle reducing the rate of cell division and possibly also cell migration. Cells were incubated in sterile 6 cm dishes until 100% confluence. After the treatments, a cross-shaped wound was made, and the medium was replaced by fresh culture medium containing serum (0 hours). Wound closure was monitored for 24 hours. 0 hours: start of monitoring. 24 hours: completion of the trial. Magnification: 4X.

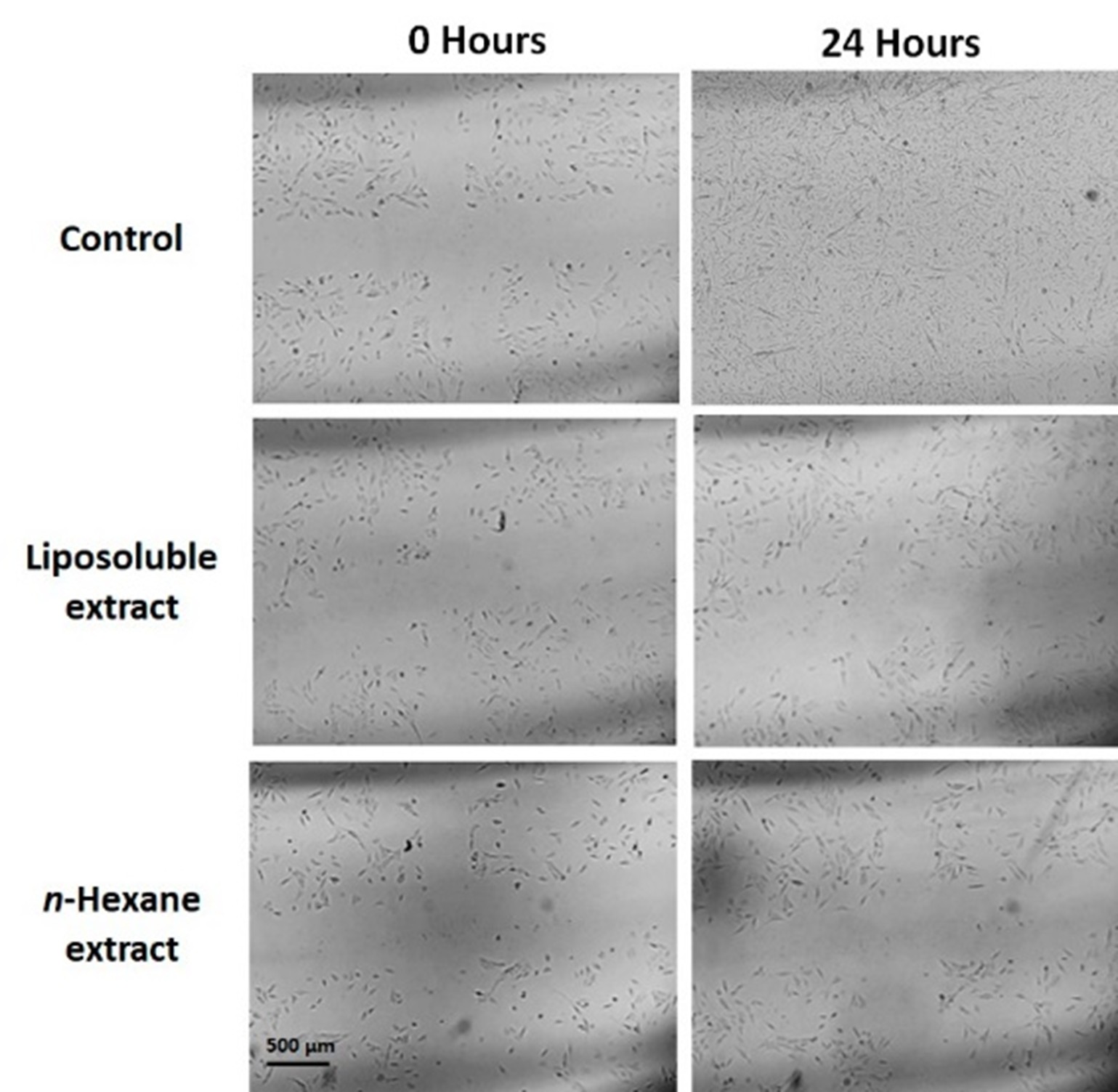

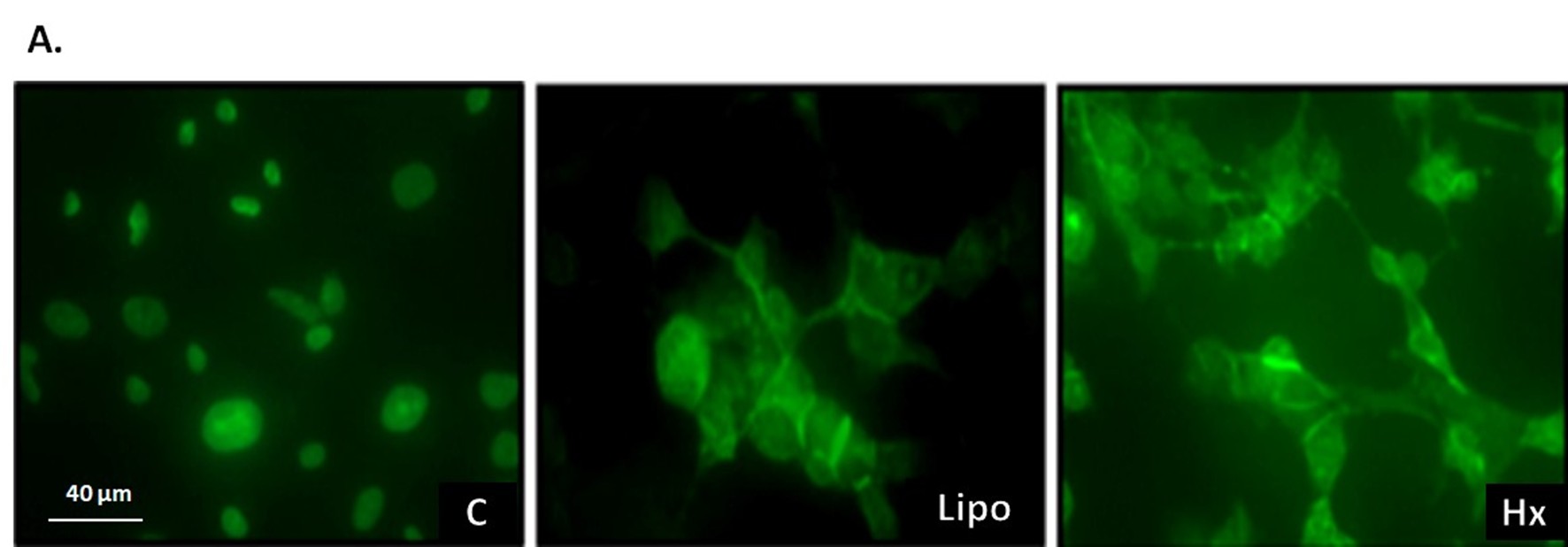

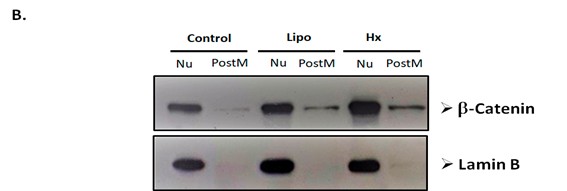

N. glauca extracts induced the nuclear localization of β-catenin protein in RD cell line

As a first approach to investigate the effect of N. glauca extracts on the subcellular localization of β-catenin, we initially studied its localization under basal conditions in the RD cell line, comparing results with the non-tumor C2C12 cell line. Thus, immunocytochemical assays were performed using a specific antibody against β-catenin to evaluate its localization in both RD and C2C12 cells. We observed that non-tumor cells exhibited a cytoplasmic localization of β-catenin near the cell membrane, whereas RD cells showed nuclear localization (Figure 3). Immunocytochemistry after treatments, revealed a change in the subcellular localization of β-catenin in the RD cell line after exposure to the liposoluble extract and n-hexane sub-extract. Untreated RD cells showed nuclear β-catenin localization, whereas treated cells exhibited increased cytosolic localization (Figure 4A). Western blot analysis further confirmed these effects, showing that, although no changes were observed in the nuclear fraction, an increase in β-catenin localization was detected in the post-mitochondrial fraction following treatment with both the liposoluble extract and the n-hexane sub-extract (Figure 4B). Lamin B detection was used as a control to verify the absence of nuclear contamination in the post-mitochondrial fraction.

Figure 3: β-catenin is localized in the nucleus of RD tumor cells. Immunocytochemistry assays using a primary antibody specific against β-catenin and then a secondary conjugated to a fluorophore (Alexa 488). A. C2C12 cells: β-catenin with cytoplasmic and membrane-proximal localization. B. RD cells: β-catenin with nuclear localization. Magnification: 63X.

Figure 4: Extracts from N. glauca induce changes in the subcellular localization of β-catenin protein in RD cells. A. Cells cultured on coverslips were treated for 1 hour with the vehicle of the extracts (C), with the liposoluble extract (Lipo) or with the n-hexane sub extract (Hx). Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with a primary antibody specific for β-catenin and a fluorophore-labeled secondary antibody. Nuclear localization was observed in the control (C). In the cells treated with the extracts (Lipo and Hx), β-catenin was detected in the nucleus and cytosol, mainly located near the plasmatic membrane. Magnification: 63X. B. The subcellular fractions obtained after the different treatments were isolated and quantified. 20 µg of protein from each fraction were analyzed by Western blot assays. The membranes were incubated using a specific antibody against β-catenin and subsequently with the peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, as detailed in Methods. The nuclear fraction (Nu) and the post-mitochondrial fraction (PostM) were evaluated under control conditions (C), liposoluble extract (Lipo) and n hexane sub extract (Hx).

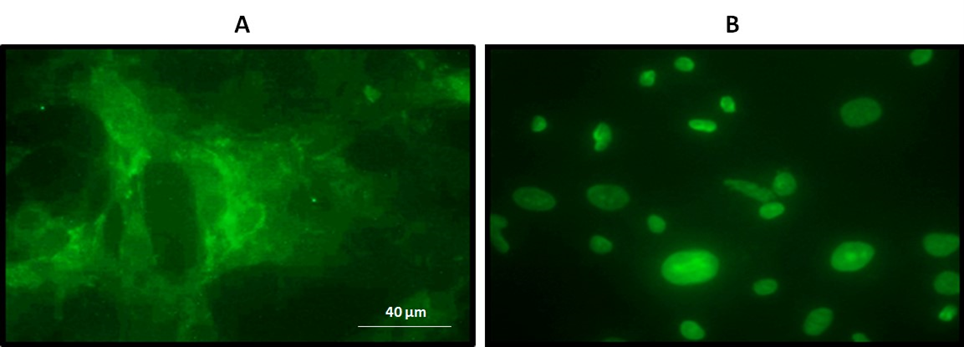

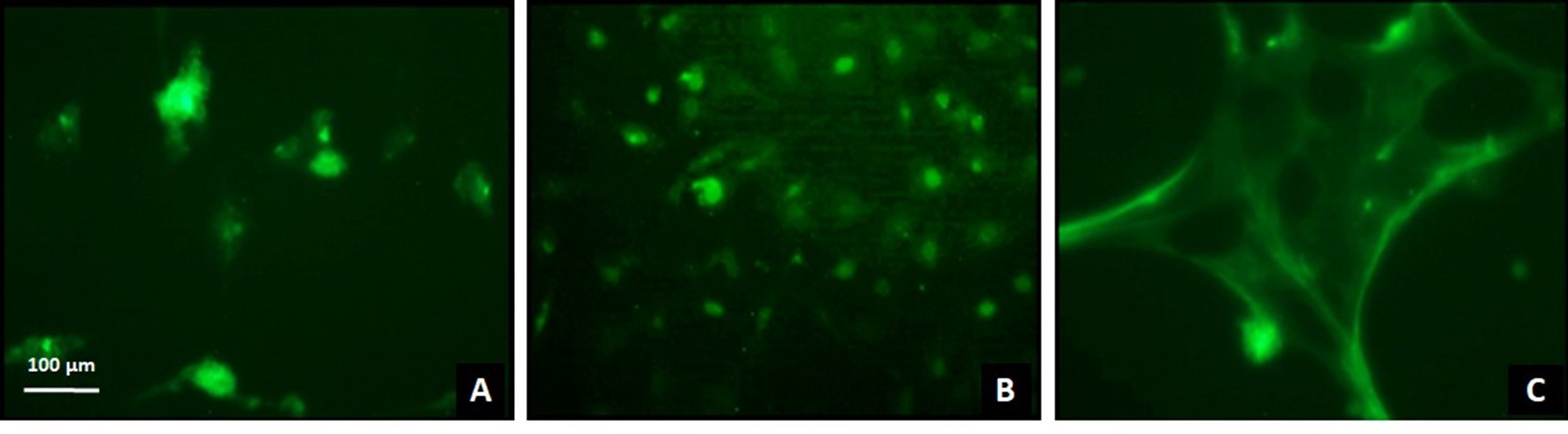

N. glauca extracts reduced cleavage and nuclear localization of the intracellular fragment of Notch 1 in RD cells

Immunocytochemical assays using a specific antibody against the intracellular fragment of Notch 1 were performed to assess its localization under both basal conditions and after treatment. Under basal conditions, the intracellular fragment of Notch 1 was predominantly localized in the nucleus (Figure 5A). Treatment with the liposoluble extract decreased the nuclear localization of the fragment (Figure 5B), while treatment with the n-hexane sub-extract resulted in its localization near the plasma membrane (Figure 5C). These findings indicate that N. glauca extracts reduce the cleavage and nuclear translocation of the intracellular region of the Notch 1 protein in the RD cell line.

Figure 5: Treatment with N. glauca extracts reduces cleavage and nuclear localization of the intracellular fragment of Notch 1 in RD cells. Cells were seeded on coverslips, treated with the liposoluble extract (B), the n-hexane sub-extract (C) or untreated (A) and subsequently fixed and permeabilized with methanol. A primary antibody directed specifically against the intracellular region of Notch 1 and a secondary antibody conjugated to the Alexa 488 fluorophore were used, as described in Methods. Magnification: 20X.

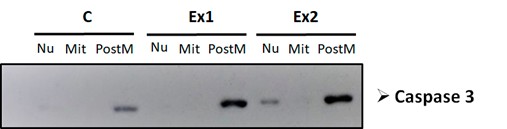

The liposoluble extract of N. glauca increases the cleaved form of Caspase 3 and its nuclear localization

Western blot assays using a specific antibody against the cleaved (active) form of the proapoptotic protein Caspase 3 demonstrated an increased detection of the cleaved fragment in the post-mitochondrial fraction, followed by its translocation to the nucleus in a time-dependent manner (Figure 6), being its nuclear localization observed after 2 hours of treatment with the liposoluble extract. These findings indicate that N. glauca extracts increase the activation and nuclear localization of Caspase 3 in RD cell line.

Figure 6: The liposoluble extract of N. glauca increases the cleaved (active) form of Caspase 3 and its nuclear localization. The subcellular fractions obtained after the different treatments were isolated and quantified. 20 µg of protein from each fraction were analyzed by Western blot assays. The membranes were incubated using a specific antibody against the active form of Caspase 3. The nuclear (Nu), mitochondrial (Mit) and the post-mitochondrial fraction (PostM) obtained from cells treated with the liposoluble extract for 1 hour (Ex 1), 2 hours (Ex 2), and cells maintained in DMEM (C) were analyzed.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the study focused on the cellular changes associated with apoptosis, particularly in RD cells treated with extract of N. glauca. First, nuclear condensation, a prominent characteristic of apoptosis, was observed through DNA staining with DAPI. This staining revealed significant morphological changes in cell nuclei, deviating from their usual rounded and well-defined shape, indicative of apoptosis. Second, mitochondrial morphology and distribution were assessed using MTT red fluorescence dye. Treatment with the extract disrupted the typical mitochondrial organization, causing mitochondria to gather around the nucleus, a hallmark of apoptosis. Additionally, a wound assay demonstrated that the extract inhibited the proliferation and migration of RD cells, suggesting potential therapeutic implications. The study also explored the expression and subcellular localization of key proteins, notably β-catenin, Notch1, and Caspase 3. The treatments induced significant changes in the subcellular location of these proteins, impacting their functions in signaling pathways related to cell migration, invasion, and apoptosis. Notch1 and β-catenin play critical roles in regulating genes associated with cell migration and invasion, and their altered localization during apoptosis disrupted these pathways, affecting the oncogenic properties of RD cells. The Caspase 3 activation was also observed, further confirming the induction of apoptosis by the extract. The study’s future goal is to identify and characterize the specific molecules within the extracts responsible for these effects, with the aim of developing novel therapeutic strategies, particularly those that trigger cell differentiation to counteract uncontrolled growth and malignant of these cells.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from Universidad Nacional del Sur (UNS) and Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

2. De Jesus FC, Rocio CC, Roberto RL, Araceli CT. Rhabdomyosarcoma, 7 years experience at the National Institute of Pediatrics. Gaceta Mexicana De Oncologia. 2010;9(5):198-207.

3. Chen J, Liu X, Lan J, Li T, She C, Zhang Q, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma in adults: case series and literature review. International Journal of Women's Health. 2022 Mar 28:405-14.

4. Skapek SX, Ferrari A, Gupta AA, Lupo PJ, Butler E, Shipley J, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers [Internet]. 2019 Dec 7;5(1):1.

5. Fontana AM. El papel de la vía Notch en Rabdomiosarcoma. 2013

6. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000 Jan 7;100(1):57-70.

7. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011 Mar 4;144(5):646-74.

8. Wanagat J, Cao Z, Pathare P, Aiken JM. Mitochondrial DNA deletion mutations colocalize with segmental electron transport system abnormalities, muscle fiber atrophy, fiber splitting, and oxidative damage in sarcopenia. The FASEB Journal. 2001 Feb;15(2):322-32.

9. Jubrias SA, Esselman PC, Price LB, Cress ME, Conley KE. Large energetic adaptations of elderly muscle to resistance and endurance training. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2001 May 1;90(5):1663-70.

10. La Colla A, Vasconsuelo A, Milanesi L, Pronsato L. 17β‐Estradiol protects skeletal myoblasts from apoptosis through p53, Bcl‐2, and FoxO families. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2017 Jan;118(1):104-15.

11. La Colla AB. 17ß-estradiol promueve la sobrevida del músculo esquelético: mitocondria como blanco estrogénico, acción antipoptótica y vías de señalización intracelular. 2015.

12. La Colla A, Pronsato L, Milanesi L, Vasconsuelo A. 17β-Estradiol and testosterone in sarcopenia: Role of satellite cells. Ageing Research Reviews. 2015 Nov 1;24:166-77.

13. Pronsato L, Milanesi L, Vasconsuelo A, La Colla A. Testosterone modulates FoxO3a and p53-related genes to protect C2C12 skeletal muscle cells against apoptosis. Steroids. 2017 Aug 1;124:35-45.

14. Pronsato L, La Colla A, Ronda AC, Milanesi L, Boland R, Vasconsuelo A. High passage numbers induce resistance to apoptosis in C2C12 muscle cells. Biocell. 2013 Apr;37(1):1-9.

15. la Colla AB, Pronsato L, Ronda AC, Milanesi LM, Vasconsuelo AA, Boland RL. 17B-Estradiol and Testosterone Protect Mitochondria Against Oxidative Stress in Skeletal Muscle Cells. Actualizaciones en Osteología. 2014;10(2):122–35.

16. Yoshida N, Yoshida S, Koishi K, Masuda K, Nabeshima YI. Cell heterogeneity upon myogenic differentiation: down-regulation of MyoD and Myf-5 generates ‘reserve cells’. Journal of Cell Science. 1998 Mar 15;111(6):769-79.

17. Musso F, Lincor D, Vasconsuelo A, Pronsato L, Faraoni B, Milanesi L. Adverse effects in skeletal muscle following the medicinal use of Nicotiana glauca. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2019 May 1;42(5):671-9.

18. Milanesi L, Monje P, Boland R. Presence of estrogens and estrogen receptor-like proteins in Solanum glaucophyllum. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2001 Dec 21;289(5):1175-9.

19. Musso F, Pronsato L, Milanesi L, Vasconsuelo A, Faraoni MB. Non-polar extracts of Nicotiana glauca (Solanaceae) induce apoptosis in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Rodriguésia. 2020 Jul 13;71:01012019.

20. Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Canadian Journal of Biochemistry and Physiology. 1959 Aug 1;37(8):911-7.

21. Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analytical Biochemistry. 1976 May 7;72(1-2):248-54.

22. Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680-5.

23. Di Rienzo JA, Guzmán AW, Casanoves F. A multiple-comparisons method based on the distribution of the root node distance of a binary tree. Journal of Agricultural, Biological, and Environmental Statistics. 2002 Jun;7:129-42.

24. Garcia M, Vecino E. Intracellular pathways leading to apoptosis of retinal cells. Archivos de la Sociedad Espanola de Oftalmologia. 2003 Jul 1;78(7):351-64.