Abstract

Autoimmune hepatitis and post-transplant alloimmune hepatitis are inflammatory conditions observed in the native and transplanted liver respectively. Regulatory T cells play a crucial role in the maintenance of immune tolerance and prevention of autoimmunity. Endoplasmic reticulum stress with unfolded protein response activation have been reported in circulating regulatory T cells suggesting a possible link between them. This review explores the role of regulatory T cells in autoimmunity focusing on their function and regulation in the liver. It also highlights the involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress and unfolded protein response activation in autoimmune diseases. Understanding the interplay between endoplasmic reticulum stress, unfolded protein response activation and regulatory T cells may provide insights into disease pathogenesis and identify novel therapeutic targets for treatment of autoimmune liver diseases.

Keywords

Activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), Regulatory T cell dysregulation, CCAAT/enhancerbinding protein homology protein (CHOP), Human endogenous retrovirus (HERV)

Abbreviation

ABCA12: ATP-Binding Cassette A12; ATF4: Activating Transcription Factor 4; ATF6: Activating Transcription Factor 6; ATP: Adenosine Triphosphate; BiP: Binding Immunoglobulin Protein; C/EBPβ: CCAAT/Enhancer-Binding Protein Beta; CHOP: CCAAT/Enhancer?Binding Protein Homology Protein; CXCR4: CXC Motif Chemokine Receptor 4; dnAIH: De novo Autoimmune Hepatitis; EIF2α-p: Phosphorylated Translation Initiation Factor; Env-HERV1: Envelope Protein of HERV1_I; ER: Endoplasmic Reticulum; ERAD: ER-Associated Protein Degradation; FOXP3: Forkhead Box Protein P3; Gal9: Galectin-9; IRE1: Inositol-Requiring Enzyme 1; KLF4: Krüppel-like Factor 4; LAG3: Lymphocyte Activation Gene 3; PD-1: Programmed Cell Death Protein 1; PERK: Protein Kinase RNA-like ER kinase; pSTAT-5: Phospho Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 5; RA: Rheumatoid Arthritis; RORC: RAR Related Orphan Receptor C; SLE: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus; STAT3: Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3; T1D: Type 1 Diabetes; TCR: T cell Receptor; Tim-3: T cell Immunoglobulin Domain and Mucin Domain-3; TLR2: Toll-like Receptors (TLR) 2; TLR4: Toll-like Receptors (TLR) 4; Tregs: Regulatory T cells; UPR: Unfolded Protein Response; XBP1: Spliced ??X-box Protein

Introduction

The incidence and prevalence of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) globally is 1.28 per 100,000 population-years (95% CI, 1.01-1.63) and 15.65 per 100,000 population (95% CI, 13.42-18.24), respectively [1]. The incidence and prevalence in children is 0.4 and 3.0 cases per 100,000 children [2], and in adults 17 per 100,000 [3,4]. Post-transplant alloimmune hepatitis also called de novo autoimmune hepatitis (dnAIH) is an uncommon but serious condition observed in the transplanted liver that can lead to chronic rejection, graft loss, and a need for liver re-transplantation [5]. Its frequency is higher in children [6] (5%-10%) than in adults (1%-3%) [7]. Regulatory T cell (Treg) dysfunction has been observed in children with post-transplant alloimmune hepatitis, specifically, circulating Tregs of children with post-transplant alloimmune hepatitis exhibit higher frequencies of pro-inflammatory IFN-γ and IL-17 cytokines despite having a fully demethylated Foxp3 locus. The driver behind Th1-like Tregs is thought to be IL-12 production by monocytes/macrophages. Inflammasome activation of CD14+ monocytes, mediated via Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), is responsible for IL-12 production. IL-12 drives Tregs to adopt a Th1-like phenotype with aberrant production of IFN-γ, contributing to Treg dysfunction [8,9]. Downregulation of TLR2 and TLR4 on CD14+ monocytes abrogate IL-12 production by monocytes and thus IFN-g production by Tregs, resulting in partial recovery of Treg suppressor function [9]. The above reports underscore the significance of monocytes in driving the development of a proinflammatory Treg phenotype in post-transplant alloimmune hepatitis. The exact cause of AIH is not fully understood, but it is believed to involve a combination of genetic, environmental, and immunological factors. In several studies, mainly involving pediatric patients, it has been shown that peripheral blood Tregs are reduced in frequency and their function impaired [10-12]. Other observations reported include effector CD4 T cells that are less susceptible to Treg restraints; specifically, defects caused by reduced T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 (Tim-3) levels on effector T cells and Galectin-9 (Gal9) on Tregs render effector cells resistant to Treg control, implicating the failure of immune control on both sides [13]. Liver injury is perpetuated and progresses due to an imbalance between effector and regulatory cells [14]. Additionally, effector T cells are activated and produce pro-inflammatory cytokines which induces inflammation in the liver [15-17]. Th17 cell activation is also linked to liver injury in AIH, primarily through inflammation and the initiation of pro-fibrotic processes [18,19]. Reduced Treg function in AIH is associated with impaired Treg ability to produce IL-10 and Treg inability to upregulate phospho signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (pSTAT-5) in response to IL-2 [20,21]. Tissue damage and inflammation leads to elevated levels of extracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP). CD39 is an enzyme that breaks down extracellular ATP/ADP into AMP that is converted to the immunosuppressive molecule adenosine 5′-ectoenzyme CD73 [22]. An imbalance of Tregs and Th17 cells has been observed and reported in AIH and is attributed to decreased CD39 levels. Decreased CD39+ Treg frequency reduce ATP/ADP hydrolysis activity and thus conversion of ATP to adenosine, resulting in failure of suppression of IL-17 production by effector CD4 T cells [23,24], which contributes to loss of immune tolerance and AIH [23,25,26].

Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Autoimmune and Alloimmune Liver Disease

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is crucial for protein synthesis, folding, and modification. When overwhelmed by oxidative stress or inflammation, misfolded proteins accumulate, leading to ER stress and triggering the unfolded protein response (UPR) [27]. The UPR is mediated by three main transmembrane proteins located in the ER membrane: inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1), protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK) and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6). These proteins are usually kept inactive by the ER chaperone protein BiP. Upon ER stress, BiP dissociates, activating these sensors and initiating the UPR signaling cascade [28,29]. Human Endogenous Retroviruses (HERVs) induce ER stress and activate the UPR [30,31]. Dysregulation of the UPR has been implicated in the development of several human diseases [32]. We observed up-regulation of the envelope protein of HERV1_I (env-HERV1) and UPR activation in peripheral blood Tregs and livers of children with post-transplant alloimmune hepatitis and AIH. Increased levels of ATF6A, spliced ??X-box protein (XBP1s), phosphorylated translation initiation factor (eIF2α-p) and CCAAT/enhancer?binding protein homology protein (CHOP) were observed. ER stress was HERV-mediated as the envelope protein of HERV1 interacted with ATF6 in peripheral blood Tregs [33]. ER stress has been implicated in the pathogenesis of other autoimmune diseases specifically, ER stress-induced β-cell dysfunction and development of type 1 diabetes (T1D) [34], ER stress in synoviocytes and chondrocytes and development of inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients [35]. Other examples include ER stress in B cells, macrophages, T cells, dendritic cells, and neutrophils contributing to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [36–39], and ER stress in keratinocytes thought to contribute to the development of psoriasis [40].

Consequences of ER Stress and UPR Activation in Autoimmune and Alloimmune Liver Disease

The UPR affects nearly every aspect of the secretory pathway, including protein synthesis, transport to the ER, folding, maturation, quality control, protein trafficking, and the elimination of misfolded proteins by autophagy and ER- associated protein degradation (ERAD) [27,41]. In higher eukaryotes, UPR activation results in transient cell-cycle arrest at G1/S, and transcription of UPR target genes. Cells can adapt to stress or undergo apoptosis if homeostasis is not restored [42]. In post-transplant alloimmune hepatitis and AIH, peripheral blood Tregs undergo early apoptosis with increased PD1 and LAG3 expression suggesting a relationship between ER stress/unremitting UPR activation and immune checkpoint expression [33]. The association between ER stress induced apoptosis and disease pathogenesis is not limited to autoimmune/alloimmune liver disease as chronic ER stress-induced apoptosis of pancreatic β-cells in Type-1-Diabetes contributes to disease pathogenesis by reducing insulin production and secretion, while diminished activity of the transcription factors ATF6 and XBP1s inhibits adaptive responses [43]. In Rheumatoid Arthritis, ER stress-induced apoptosis in synovial fibroblasts and chondrocytes contributes to joint destruction by activating GRP78, IRE1, XBP1s, ATF6, and eIF2a-P in macrophages and synovial tissues [35,44]. Additionally, ER-stress-induced apoptosis through transcriptional activation of CHOP leads to increased anti-apoptotic molecule Bcl-2 and caspase-6 signaling pathway in T cells in SLE [45]. Lastly, ER stress induced apoptosis of keratinocytes upregulates ABCA12 and KLF4 through XBP-1, and C/EBPβ through ATF4, which drives the abnormal skin cell proliferation and differentiation observed in psoriasis [46].

Dysregulation of Immune Responses following UPR Activation

UPR activation has been linked to regulation of innate and adaptive immune responses. IRE1 and PERK signaling pathways play critical roles in modulating the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and antigen presentation [47]. UPR activation regulates differentiation, plasticity, effector function, and apoptosis of CD4+ T cells and is important to CD4+ T cell activation [48-50]. UPR activation is linked to B cell and classic dendritic cell differentiation and is necessary for antibody secretion from plasma cells [51,52]. As Tregs maintain immune tolerance and prevent autoimmunity, dysregulation of the UPR can disrupt their normal function and contribute to autoimmunity. In AIH and post-transplant alloimmune hepatitis, following UPR activation, ATF6 binds to the transcription promoter regions of RORC and STAT3 and drives Treg differentiation to Th17-like Tregs. Downregulation of UPR activation results in down regulation of the Th17 transcription factors, RORC and STAT3, and IL-17A mRNA. This is accompanied by partial recovery of Treg suppressive function supporting a relationship between UPR activation and adaptive immune response in alloimmune liver disease [33]. While we observed Treg dysregulation and dysfunction in ER-stressed peripheral blood Tregs of children with alloimmune liver disease, Feng et al. report their observation of enhanced TCR-induced activation and functional activity of BALB/c mice Tregs following thapsigargin-induced ER stress [53].

Liver Infiltrating Tregs in Autoimmune and Alloimmune Liver Disease

Liver-infiltrating Tregs are a distinct population of Tregs that migrate from the peripheral blood to the liver in response to local signals. They are enriched in the liver and exhibit unique phenotypic and functional characteristics compared to circulating Tregs [54]. They are thought to play a crucial role in modulating immune responses within the liver microenvironment particularly in the context of AIH and post-transplant alloimmune hepatitis. Ye et al. report that up to 18% of T cells in inflamed areas of the human liver with AIH are FoxP3 expressing Tregs [55]. The published literature on human liver infiltrating Tregs in AIH is varied with increased number of intrahepatic Tregs whose presence is linked to heightened activity and inflammation in the liver reported by some groups [56,57], while others report a disproportionate enrichment of intrahepatic Tregs in untreated pediatric AIH accompanied by a decrease in Treg frequency during treatment attributed to the decrease in IL-2 levels [20,58]. Taubert et al. have observed that their cohort of untreated patients with AIH have a constant Treg/T-effector ratio with no changes in Tregs in the circulation despite the presence of T-effectors in the liver. They speculate that following discontinuation of immunosuppression, high rates of relapse may be caused by a disproportional decrease of intrahepatic Tregs [58].

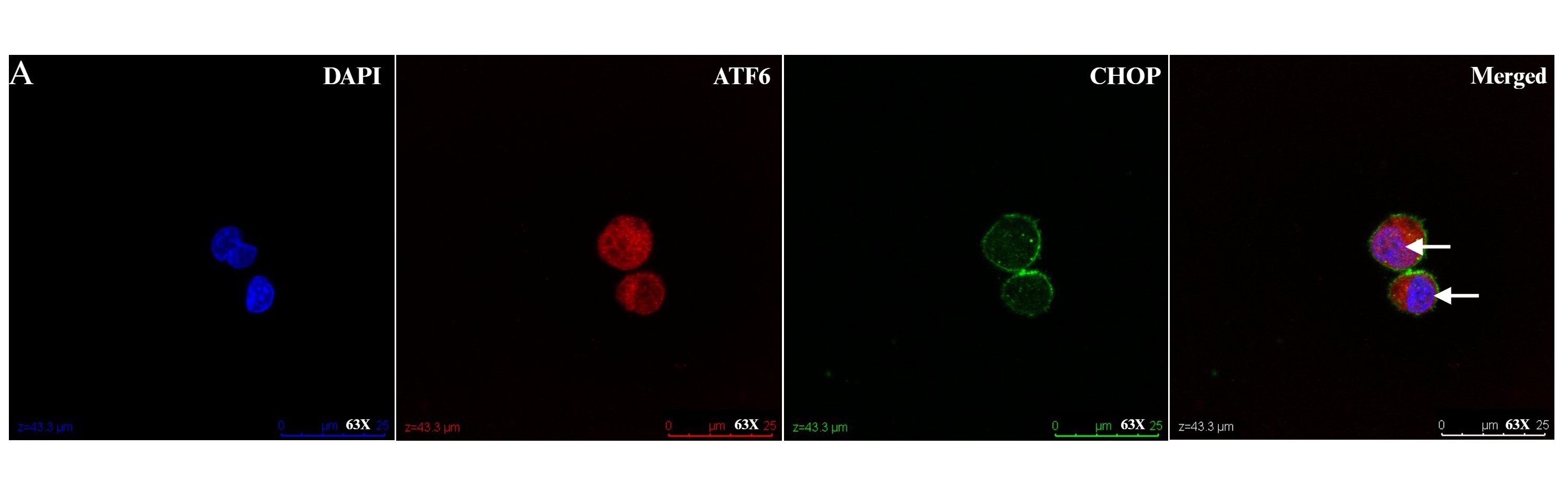

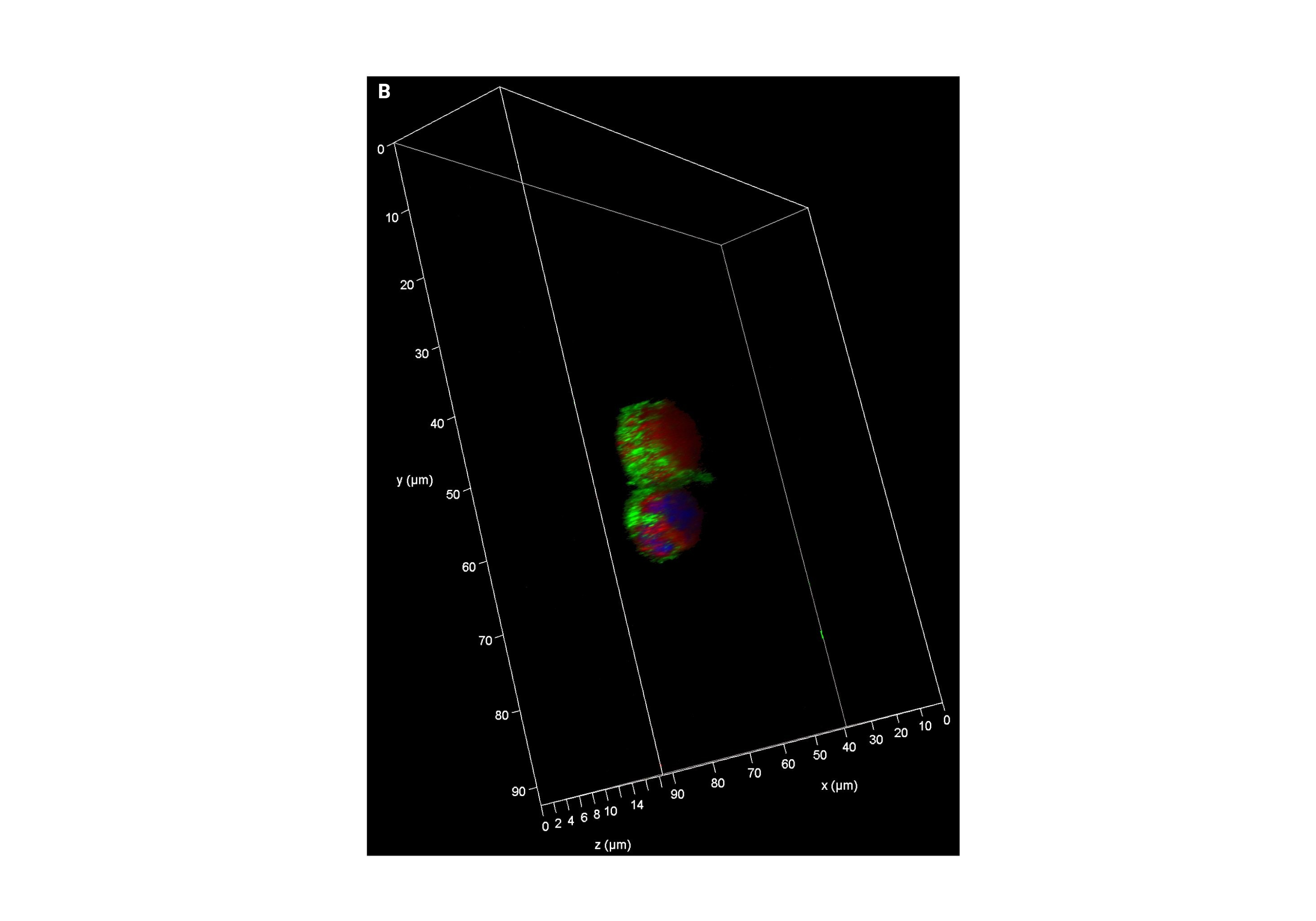

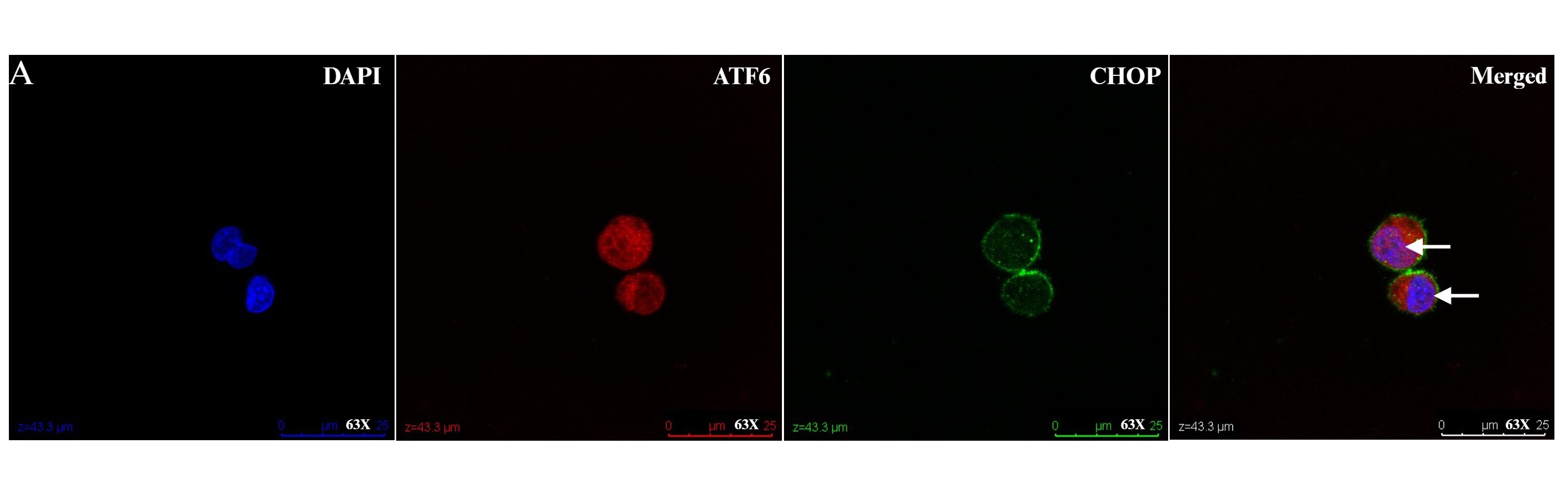

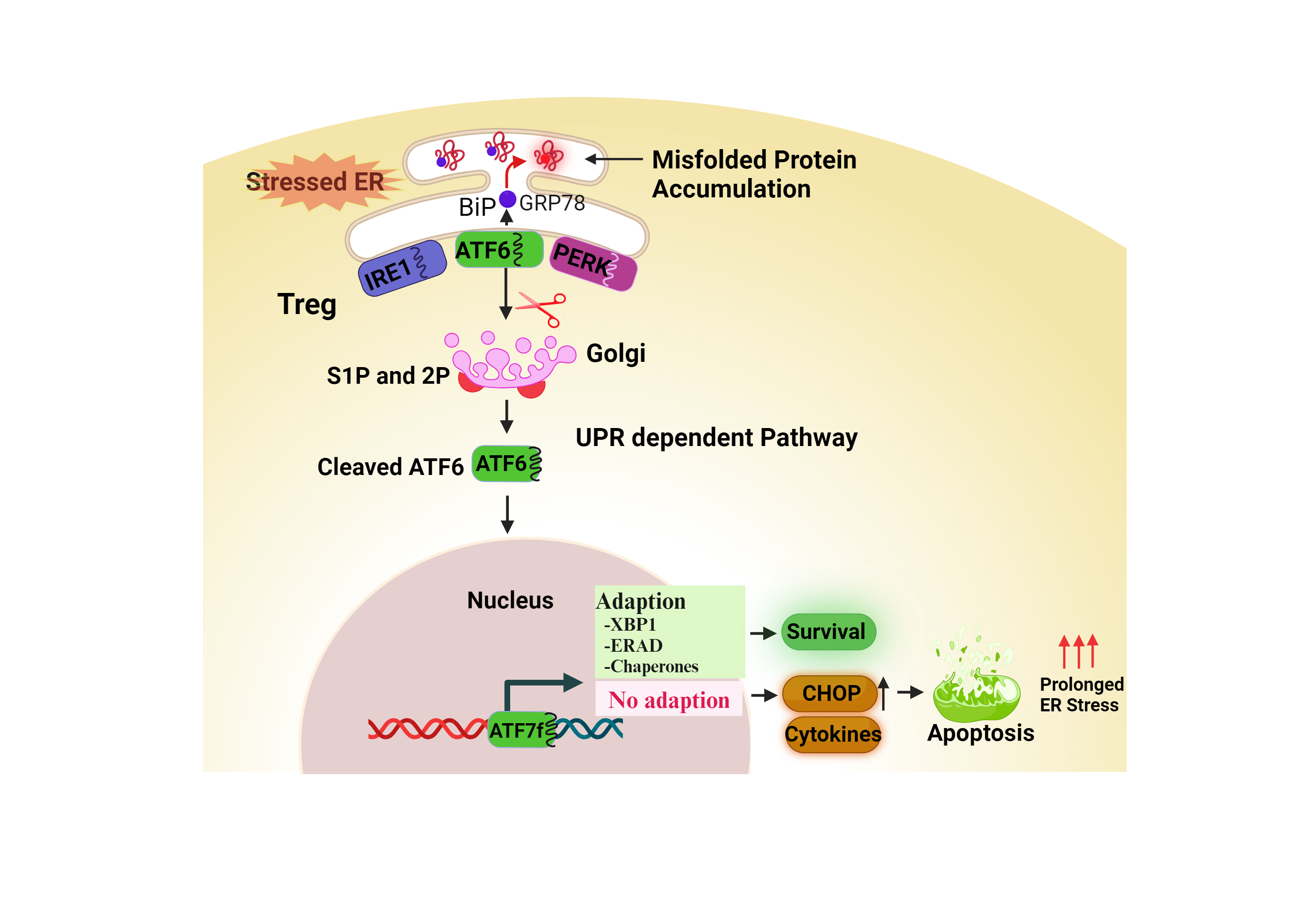

In addition to the expression of foxp3, liver infiltrating Tregs express higher levels of the chemokine receptors CXCR3 and CCR4 compared to peripheral blood Tregs [55]. This is significant in the context of a liver microenvironment that is characterized by an abundance of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-12, TNF, IFN-γ, and professional antigen-presenting dendritic cells. This microenvironment might hinder the function of intrahepatic Tregs either by impairing Treg suppression of effector cells or by increasing effector cell resistance to Treg suppression [59]. The liver microenvironment also plays a crucial role in the survival, differentiation, and apoptosis of both effector and regulatory lymphocytes [59]. Given our observation of regulation of the adaptive immune response in circulating Tregs following UPR activation, our laboratory has studied liver infiltrating Tregs in AIH and observes a suggestion of UPR activation as evidenced by ATF6a and CHOP activation (Figure 1). We propose more research that investigates crosstalk between ER stress, UPR activation and Treg function in autoimmune liver disease (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Liver infiltrating regulatory T cells (Tregs) in health and disease. Intrahepatic lymphocytes extracted from fresh liver tissue of nontrans planted control and autoimmune hepatitis patient were enriched for CD4, then stained with CD45, CD25, and CD127, before undergoing fluorescence activated cell sorting on an Aria sorter for liver infiltrating Tregs (defined as CD4+CD25hiCD127-). 1X105 liver infiltrating Tregs were cultured in TCM media with rIL-2 for 48-hours, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10-minutes, and then stained with ATF6α and CHOP. Representative confocal micrographs showing: (A) nuclear localization of ATF6 (red) in Tregs from a non-transplanted control liver (white arrow). Nuclei are labeled with DAPI (blue). There is absence of nuclear localization of CHOP (green). Scale bars 50 μm. (B) Representative Z stack confocal image acquired with 3D Leica SP8 of Tregs from a non-transplanted control liver with absence of nuclear localization of CHOP (green). Magnification 63X. (C)Representative Z stack confocal image acquired with 3D Leica SP8 of Tregs from an autoimmune hepatitis liver showing co-localization of ATF6 (red)with DAPI (blue) and CHOP (green). Magnification 63X.

Figure 2: Proposed schematic model shows the interaction between regulatory T cells (Tregs) and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress / unfolded protein response (UPR) activation indicating potential crosstalk with impact on Treg function.

Conclusion

More research is needed to clarify the complex relationship between Treg function, ER stress, and UPR activation in human autoimmune liver disease as new insights into these interactions may pave the way for development of targeted therapeutic interventions aimed at restoring immune homeostasis and mitigating liver injury.

References

2. Deneau M, Jensen MK, Holmen J, Williams MS, Book LS, Guthery SL. Primary sclerosing cholangitis, autoimmune hepatitis, and overlap in Utah children: epidemiology and natural history. Hepatology. 2013 Oct;58(4):1392-400.

3. Delgado JS, Vodonos A, Malnick S, Kriger O, Wilkof-Segev R, Delgado B, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis in southern Israel: a 15-year multicenter study. J Dig Dis. 2013 Nov;14(11):611-8.

4. Boberg KM, Aadland E, Jahnsen J, Raknerud N, Stiris M, Bell H. Incidence and prevalence of primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and autoimmune hepatitis in a Norwegian population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998 Jan;33(1):99-103.

5. Ekong UD, McKiernan P, Martinez M, Lobritto S, Kelly D, Ng VL, et al. Long-term outcomes of de novo autoimmune hepatitis in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Pediatr Transplant. 2017 Sep;21(6):10.1111/petr.12945.

6. Kerkar N, Hadzić N, Davies ET, Portmann B, Donaldson PT, Rela M, et al. De-novo autoimmune hepatitis after liver transplantation. Lancet. 1998 Feb 7;351(9100):409-13.

7. Ma L, Li M, Zhang T, Xu JQ, Cao XB, Wu SS, et al. Incidence of de novo autoimmune hepatitis in children and adolescents with increased autoantibodies after liver transplantation: a meta-analysis. Transpl Int. 2021 Mar;34(3):412-22.

8. Arterbery AS, Osafo-Addo A, Avitzur Y, Ciarleglio M, Deng Y, Lobritto SJ, et al. Production of Proinflammatory Cytokines by Monocytes in Liver-Transplanted Recipients with De Novo Autoimmune Hepatitis Is Enhanced and Induces TH1-like Regulatory T Cells. J Immunol. 2016 May 15;196(10):4040-51.

9. Arterbery AS, Yao J, Ling A, Avitzur Y, Martinez M, Lobritto S, et al. Inflammasome Priming Mediated via Toll-Like Receptors 2 and 4, Induces Th1-Like Regulatory T Cells in De Novo Autoimmune Hepatitis. Front Immunol. 2018 Jul 19;9:1612.

10. Longhi MS, Ma Y, Bogdanos DP, Cheeseman P, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Impairment of CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T-cells in autoimmune liver disease. J Hepatol. 2004 Jul;41(1):31-7.

11. Longhi MS, Hussain MJ, Mitry RR, Arora SK, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, et al. Functional study of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in health and autoimmune hepatitis. J Immunol. 2006 Apr 1;176(7):4484-91.

12. Preti M, Schlott L, Lübbering D, Krzikalla D, Müller AL, Schuran FA, et al. Failure of thymic deletion and instability of autoreactive Tregs drive autoimmunity in immune-privileged liver. JCI Insight. 2021 Mar 22;6(6):e141462.

13. Liberal R, Grant CR, Holder BS, Ma Y, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, et al. The impaired immune regulation of autoimmune hepatitis is linked to a defective galectin-9/tim-3 pathway. Hepatology. 2012 Aug;56(2):677-86.

14. Vuerich M, Wang N, Kalbasi A, Graham JJ, Longhi MS. Dysfunctional Immune Regulation in Autoimmune Hepatitis: From Pathogenesis to Novel Therapies. Front Immunol. 2021 Sep 28;12:746436.

15. Wu B, Wan Y. Molecular control of pathogenic Th17 cells in autoimmune diseases. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020 Mar;80:106187.

16. Drescher HK, Bartsch LM, Weiskirchen S, Weiskirchen R. Intrahepatic TH17/TReg Cells in Homeostasis and Disease-It's All About the Balance. Front Pharmacol. 2020 Oct 2;11:588436.

17. Longhi MS, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Regulatory T cells in autoimmune hepatitis: an updated overview. J Autoimmun. 2021 May;119:102619.

18. Beringer A, Miossec P. IL-17 and IL-17-producing cells and liver diseases, with focus on autoimmune liver diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2018 Dec;17(12):1176-85.

19. Zhao L, Tang Y, You Z, Wang Q, Liang S, Han X, et al. Interleukin-17 contributes to the pathogenesis of autoimmune hepatitis through inducing hepatic interleukin-6 expression. PLoS One. 2011 Apr 19;6(4):e18909.

20. Diestelhorst J, Junge N, Schlue J, Falk CS, Manns MP, Baumann U, et al. Pediatric autoimmune hepatitis shows a disproportionate decline of regulatory T cells in the liver and of IL-2 in the blood of patients undergoing therapy. PLoS One. 2017 Jul 11;12(7):e0181107.

21. Liberal R, Grant CR, Holder BS, Cardone J, Martinez-Llordella M, Ma Y, et al. In autoimmune hepatitis type 1 or the autoimmune hepatitis-sclerosing cholangitis variant defective regulatory T-cell responsiveness to IL-2 results in low IL-10 production and impaired suppression. Hepatology. 2015 Sep;62(3):863-75.

22. Longhi MS, Vuerich M, Kalbasi A, Kenison JE, Yeste A, Csizmadia E, et al. Bilirubin suppresses Th17 immunity in colitis by upregulating CD39. JCI Insight. 2017 May 4;2(9):e92791.

23. Longhi MS, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Regulatory T cells in autoimmune hepatitis: an updated overview. J Autoimmun. 2021 May;119:102619.

24. Maj T, Wang W, Crespo J, Zhang H, Wang W, Wei S, et al. Oxidative stress controls regulatory T cell apoptosis and suppressor activity and PD-L1-blockade resistance in tumor. Nat Immunol. 2017 Dec;18(12):1332-41.

25. Huang C, Shen Y, Shen M, Fan X, Men R, Ye T, et al. Glucose Metabolism Reprogramming of Regulatory T Cells in Concanavalin A-Induced Hepatitis. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Aug 31;12:726128.

26. Grant CR, Liberal R, Holder BS, Cardone J, Ma Y, Robson SC, et al. Dysfunctional CD39(POS) regulatory T cells and aberrant control of T-helper type 17 cells in autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2014 Mar;59(3):1007-15.

27. Na M, Yang X, Deng Y, Yin Z, Li M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease. PeerJ. 2023 Nov 14;11:e16398.

28. Corazzari M, Gagliardi M, Fimia GM, Piacentini M. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, Unfolded Protein Response, and Cancer Cell Fate. Front Oncol. 2017 Apr 26;7:78.

29. Cao SS, Kaufman RJ. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress in cell fate decision and human disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014 Jul 20;21(3):396-413.

30. Xue X, Wu X, Liu L, Liu L, Zhu F. ERVW-1 Activates ATF6-Mediated Unfolded Protein Response by Decreasing GANAB in Recent-Onset Schizophrenia. Viruses. 2023 May 31;15(6):1298.

31. Tugnet N, Rylance P, Roden D, Trela M, Nelson P. Human Endogenous Retroviruses (HERVs) and Autoimmune Rheumatic Disease: Is There a Link? Open Rheumatol J. 2013 Mar 22;7:13-21.

32. Shreya S, Grosset CF, Jain BP. Unfolded Protein Response Signaling in Liver Disorders: A 2023 Updated Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Sep 14;24(18):14066.

33. Subramanian K, Paul S, Libby A, Patterson J, Arterbery A, Knight J, et al. HERV1-env Induces Unfolded Protein Response Activation in Autoimmune Liver Disease: A Potential Mechanism for Regulatory T Cell Dysfunction. J Immunol. 2023 Mar 15;210(6):732-744.

34. Oyadomari S, Takeda K, Takiguchi M, Gotoh T, Matsumoto M, Wada I, et al. Nitric oxide-induced apoptosis in pancreatic beta cells is mediated by the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 Sep 11;98(19):10845-50.

35. Kabala PA, Angiolilli C, Yeremenko N, Grabiec AM, Giovannone B, Pots D, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress cooperates with Toll-like receptor ligation in driving activation of rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017 Sep 18;19(1):207.

36. Li HY, Huang LF, Huang XR, Wu D, Chen XC, Tang JX, et al. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Lupus Nephritis: Potential Therapeutic Target. J Immunol Res. 2023 Aug 31;2023:7625817.

37. Zhuang H, Hudson E, Han S, Arja RD, Hui W, Lu L, et al. Microvascular lung injury and endoplasmic reticulum stress in systemic lupus erythematosus-associated alveolar hemorrhage and pulmonary vasculitis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2022 Dec 1;323(6):L715-L729.

38. Sule G, Abuaita BH, Steffes PA, Fernandes AT, Estes SK, Dobry C, Pandian D, Gudjonsson JE, Kahlenberg JM, O'Riordan MX, Knight JS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress sensor IRE1α propels neutrophil hyperactivity in lupus. J Clin Invest. 2021 Apr 1;131(7):e137866.

39. Wang J, Cheng Q, Wang X, Zu B, Xu J, Xu Y, Zuo X, Shen Y, Wang J, Shen Y. Deficiency of IRE1 and PERK signal pathways in systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Med Sci. 2014 Dec;348(6):465-73.

40. Zhao M, Luo J, Xiao B, Tang H, Song F, Ding X, Yang G. Endoplasmic reticulum stress links psoriasis vulgaris with keratinocyte inflammation. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2020 Feb;37(1):34-40.

41. Hetz C, Zhang K, Kaufman RJ. Mechanisms, regulation and functions of the unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020 Aug;21(8):421-38.

42. Hagenlocher C, Siebert R, Taschke B, Wieske S, Hausser A, Rehm M. ER stress-induced cell death proceeds independently of the TRAIL-R2 signaling axis in pancreatic β cells. Cell Death Discov. 2022 Jan 24;8(1):34.

43. Engin F, Yermalovich A, Nguyen T, Hummasti S, Fu W, Eizirik DL, et al. Restoration of the unfolded protein response in pancreatic β cells protects mice against type 1 diabetes. Sci Transl Med. 2013 Nov 13;5(211):211ra156.

44. Barrera MJ, Aguilera S, Castro I, González S, Carvajal P, Molina C, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in autoimmune diseases: Can altered protein quality control and/or unfolded protein response contribute to autoimmunity? A critical review on Sjögren's syndrome. Autoimmun Rev. 2018 Aug;17(8):796-808.

45. Lee WS, Sung MS, Lee EG, Yoo HG, Cheon YH, Chae HJ, et al. A pathogenic role for ER stress-induced autophagy and ER chaperone GRP78/BiP in T lymphocyte systemic lupus erythematosus. J Leukoc Biol. 2015 Feb;97(2):425-33.

46. Sugiura K. Unfolded protein response in keratinocytes: impact on normal and abnormal keratinization. J Dermatol Sci. 2013 Mar;69(3):181-6.

47. Li A, Song NJ, Riesenberg BP, Li Z. The Emerging Roles of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Balancing Immunity and Tolerance in Health and Diseases: Mechanisms and Opportunities. Front Immunol. 2020 Feb 11;10:3154.

48. Brucklacher-Waldert V, Ferreira C, Stebegg M, Fesneau O, Innocentin S, Marie JC, et al. Cellular Stress in the Context of an Inflammatory Environment Supports TGF-β-Independent T Helper-17 Differentiation. Cell Rep. 2017 Jun 13;19(11):2357-70.

49. Lee YK, Mukasa R, Hatton RD, Weaver CT. Developmental plasticity of Th17 and Treg cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009 Jun;21(3):274-80.

50. Scheu S, Stetson DB, Reinhardt RL, Leber JH, Mohrs M, Locksley RM. Activation of the integrated stress response during T helper cell differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2006 Jun;7(6):644-51.

51. Tellier J, Shi W, Minnich M, Liao Y, Crawford S, Smyth GK, et al. Blimp-1 controls plasma cell function through the regulation of immunoglobulin secretion and the unfolded protein response. Nat Immunol. 2016 Mar;17(3):323-30.

52. Ravindran R, Loebbermann J, Nakaya HI, Khan N, Ma H, Gama L, et al. The amino acid sensor GCN2 controls gut inflammation by inhibiting inflammasome activation. Nature. 2016 Mar 24;531(7595):523-27.

53. Feng ZZ, Luo N, Liu Y, Hu JN, Ma T, Yao YM. ER stress and its PERK branch enhance TCR-induced activation in regulatory T cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021 Jul 23;563:8-14.

54. Klugewitz K, Blumenthal-Barby F, Eulenburg K, Emoto M, Hamann A. The spectrum of lymphoid subsets preferentially recruited into the liver reflects that of resident populations. Immunol Lett. 2004 May 15;93(2-3):159-62.

55. Oo YH, Weston CJ, Lalor PF, Curbishley SM, Withers DR, Reynolds GM, et al. Distinct roles for CCR4 and CXCR3 in the recruitment and positioning of regulatory T cells in the inflamed human liver. J Immunol. 2010 Mar 15;184(6):2886-98.

56. Behairy BE, El-Araby HA, Abd El Kader HH, Ehsan NA, Salem ME, Zakaria HM, et al. Assessment of intrahepatic regulatory T cells in children with autoimmune hepatitis. Ann Hepatol. 2016 Sep-Oct;15(5):682-90.

57. Peiseler M, Sebode M, Franke B, Wortmann F, Schwinge D, Quaas A, et al. FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in autoimmune hepatitis are fully functional and not reduced in frequency. J Hepatol. 2012 Jul;57(1):125-32.

58. Taubert R, Hardtke-Wolenski M, Noyan F, Wilms A, Baumann AK, Schlue J, et al. Intrahepatic regulatory T cells in autoimmune hepatitis are associated with treatment response and depleted with current therapies. J Hepatol. 2014 Nov;61(5):1106-14.

59. Oo YH, Adams DH. Regulatory T cells and autoimmune hepatitis: what happens in the liver stays in the liver. J Hepatol. 2014 Nov;61(5):973-5.