Commentary

The human brain is a complex network of billions of neurons accompanied by astrocytes and microglia among others [1]. Neurons communicate via specialized sites of cell-cell contacts called synapses, where information is transmitted via the presynaptic release of neurotransmitter from synaptic vesicles (SVs) [2]. Through the integration of information transmitted via large networks of neurons, complex tasks, such as learning, memory and various behaviors, are regulated. Hence synapses are very important functional units, operating largely autonomously, with the capacity to not only mediate neurotransmission but also undergo stable changes in synaptic strength whilst maintaining their own integrity.

A fundamental open question in the field is how synapses implement and coordinate these various tasks. One emerging concept is that structural scaffold proteins of the pre- (Munc13, Rim, Piccolo Bassoon) [3] and post-synapse (PSD95, Shank3, Homer) [4] act locally to regulate these different cellular functions both in time and space.

In this commentary, we will focus on the emerging role of one large (560 kDa) scaffold protein named Piccolo, which is located at the presynaptic active zone [5]. Piccolo consists of 10 Piccolo/Bassoon homology domains (PBH), two N-terminal zinc finger (ZF) domains, three coiled-coil (CC) domains, a single PDZ domain and two C-terminal C2 domains (C2A/C2B) [6]. It is highly expressed in neuronal growth cones and is one of the first proteins recruited to nascent synapses [7,8]. Within the brain, Piccolo is present at all synaptic subtypes [5,6,9] and the neuromuscular junction [10,11]. Strong immunoreactivity can be observed in the cerebrum, cerebellum, hippocampus and olfactory bulb [5,12]. The majority of literature focuses on Piccolo’s role at synapses. There, functions range from its involvement in presynaptic actin dynamics and regulation of SV release/recycling to the maintenance of synapse integrity and regulation of degradation [3,13]. Intriguingly, recent studies show that Piccolo is also expressed in numerous cell types outside the brain including photoreceptor cells in the retina, hair cells in the cochlea, hormone releasing cells in the pituitary and insulin secreting islet cells of the pancreas [12]. Although less is known about its functions outside the brain, its broad distribution indicates that Piccolo might have wider, more pleiotropic, cellular roles than initially anticipated. This has become especially apparent through studies which link single point mutations (SNPs) within the PCLO gene with several symptomatic diseases such as major depressive disorder and Pontocerebellar Hypoplasia type 3 (PCH3) [14,15].

Of particular interest is PCH3, which is a rare but devastating disease wherein patients display severe developmental delay, progressive microcephaly with brachycephaly, seizures, hypertonia with hyperreflexia and short stature [16,17]. This particular link strongly suggests that Piccolo might have thus far unknown and underestimated functions in the brain, which might be independent of its previously documented synaptic functions. To explore these concepts further, we characterized the brains of a recently generated Piccolo knockout rat model (Pclogt/gt) [18,19] that carries many of the core phenotypes seen in patients with PCH3 [18].

Our initial anatomical studies revealed striking changes in brain morphology at 3 months of age including thinner cerebral cortex, reduced volume of the cerebellum and of the pons. Behavioral and functional studies revealed that Pclogt/gt rats had impaired motor control and the presence of seizures [18,19], in common with features of PCH3.

One hallmark of PCH3 is a smaller cerebellum [20], which we also observed in Pclogt/gt brains [18]. A detailed analysis of this brain region revealed a dramatic reduction in the number of cerebellar granule cells, which could account for its reduced size in patients with PCH3. Intriguingly, we also observed a dramatic alteration in the morphology of mossy fiber (MF) terminals, the primary afferent fiber from the pons and brainstem. These smaller and disorganized MF- rosettes are predicted to lead to reduced synaptic input into the cerebellum, which could account for motor deficits seen in Pclogt/gt rats and patients with PCH3 [18]. Of note, we also observed a hyperinnervation of climbing fibers onto dendrites of Purkinje cells and reduced expression of GABAergic receptors on cerebellar granule cells [18]. Consequently, these observed perturbations of the cerebellar microcircuit could explain how the loss of Piccolo leads to impaired motor control as well as related phenotypes [18].

Although this initial study provides some hints to potential mechanisms underlying PCH3, it remains unclear how the loss of Piccolo contributes to each of the observed changes. Given the general role of Piccolo in the regulated release/secretion of hormones (such as FSH and insulin) and neurotransmitters [3,19,21], it is possible that some observed phenotypes relate to abnormalities associated with the release and detection of such factors; known to regulate cell number, cell migration and the maturation of synaptic contacts, among others. Of note, Wnt signaling is known to play an important role in the maturation of cerebellar MF synapses [22,23]. Intriguingly, Wnt-7a KO mice have smaller cerebellar MF rosettes - comparable to the phenotype we observe in Pclogt/gt rats [18,22]. Given the changes in the maturation of MF terminals and the link between Piccolo and the Wnt signaling pathway [13], it seems reasonable to speculate that altered MF-rosettes are associated with impaired Wnt signaling.

Consistently, RNAseq data from whole-brain tissue of Pclogt/gt rats revealed changes in Wnt signaling pathways [19]. Together these data lead to the hypothesis that the formation of smaller, more disorganized cerebellar MF synapses in animals lacking Piccolo is due to impaired Wnt signaling between cerebellar granule cells and axons/growth-cones from pontine or brainstem neurons.

As an initial test of this concept, we established primary cultures of pontine explants. This in vitro system has the advantage that one can easily manipulate growth conditions, for example, by the addition of growth factors [24]. Importantly, previous studies have shown that Wnt-7a, which is released from cerebellar granule cells, can act on axons and growth cones of pontine neurons and promote their size [22,23]. Given that Piccolo is concentrated in axonal growth cones [8], we speculated that loss of Piccolo could disrupt the reception of this signal. We thus grew pontine explants from Pclowt/wt and Pclogt/gt animals either with or without Wnt-7a added to the medium. The extent of axonal growth was evaluated after 3 days in vitro (DIV3) (Figure 1A). Cells were fixed and stained for tau as an axonal marker and GAP43 as a marker for growth cones [25]. Representative images reveal that axons and growth cones are readily formed by neurons from both genotypes (Figure 1A). A more detailed analysis of the growth cones at DIV1 revealed that, whilst there were no differences in the size of growth cones between Pclowt/wt and Pclogt/gt explants, Pclogt/gt growth cones failed to increase their area upon treatment with Wnt-7a (mean area normalized to Pclowt/wt: Pclowt/wt=1; Pclowt/wt+Wnt-7a=1.548; Pclogt/gt=0.932, Pclogt/gt+Wnt-7a=0.866) (Figures 1B, 1C). In terms of growth cone complexity, calculated by the perimeter2/area of growth cones, no significant differences were found between conditions (Pclowt/wt=1 a.u.±0.0689, n=48 growth cones; Pclowt/wt+Wnt-7a=1.52±0.0967, n=53 growth cones; Pclogt/gt=0.921±0.113, n=49 growth cones; Pclogt/gt+Wnt-7a=0.801±0.0942, n=51 growth cones) (Figures 1B, 1D). These data indicate that pontine axons lacking Piccolo are less responsive to Wnt-7a, a feature that may contribute to the defects in maturation of cerebella MF synapses. They also suggest a close relationship between Piccolo and Wnt signaling within axonal growth cones [8]. At present, it is unclear how loss of Piccolo impairs Wnt signaling. One possibility is that it affects the surface expression of the Wnt receptor Frizzled. Alternatively, its loss affects downstream signaling events linked to changes in growth cone size via actin. The latter is compatible with data showing that Piccolo is a key regulator of F-actin assembly via its direct association with Profilin and Daam1 [13], which are activated via the Wnt/Frizzled/Disheveled signaling complex [26]. Future studies are needed to resolve this mechanism further and to ascertain whether impaired Wnt signaling is the underlying mechanism causing smaller cerebellar MF synapses.

Figure 1: Growth cones lacking Piccolo are less receptive to Wnt-7a.

(A) Pontine explants were fixed at DIV 3 and stained for Tau as an axonal marker and for GAP-43 as a marker for developing growth cones. Scale bar=50 μm. Axons grow from both explants, Pclowt/wt as well as Pclogt/gt. No differences are detectable considering axon length and density.

(B) Example images of MF growth cones from pontine explants treated or untreated with Wnt-7a and stained with antibodies against GAP-43 to label growth cones and Beta-tubulin to label microtubules. Pclowt/wt growth cones become more complex and larger upon treatment with Wnt-7a. Pclogt/gt growth cones do not respond to Wnt-7a treatment.

(C) Quantification of growth cone area of Pclowt/wt and Pclogt/gt pontine explants untreated or treated with Wnt-7a. Pclowt/wt growth cones increase in size upon treated with Wnt-7a but Pclogt/gt do not show a change (Pclowt/wt = 1 ±0.0534, n = 48 growth cones; Pclowt/wt+Wnt-7a=1.548 ± 0.169, n=53 growth cones; Pclogt/gt = 0.932 ± 0.0711, n=49 growth cones; Pclogt/gt + Wnt-7a=0.866 ± 0.0511, n=51 growth cones; 3 independent experiments, 2-way ANOVA, Pclowt/wt treated vs. untreated, p*** =0.0004; Pclogt/gt treated vs. untreated , p=0.877).

(D) Quantification of normalized growth cone complexity of Pclowt/wt and Pclogt/gt pontine explants untreated or treated with Wnt-7a. No significant changes were observed across conditions (Pclowt/wt=1 a.u. ± 0.0689, n=48 growth cones; Pclowt/wt + Wnt-7a=1.52 ± 0.0967, n=53 growth cones; Pclogt/ gt=0.921 ± 0.113, n=49 growth cones; Pclogt/gt+Wnt-7a=0.801 ± 0.0942, n=51 growth cones; 3 independent experiments, 2-way ANOVA, Pclowt/wt treated vs. untreated, p=0.449; Pclogt/gt treated vs. untreated, p=0.615). Scale bar=20. Error bars represent SEM. Data points represent individual growth cones.

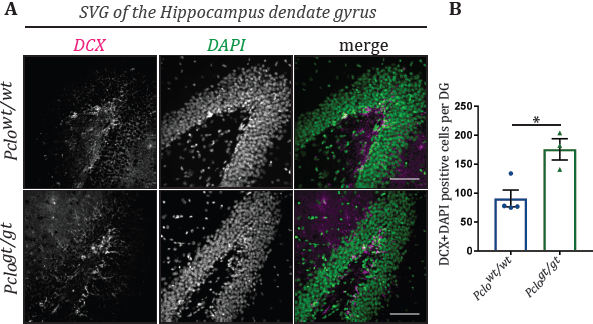

Although the most prominent phenotype of the Pclogt/gt rat is a smaller cerebellum and pons [18], Piccolo is not exclusively expressed in the cerebellum, it is expressed throughout the brain [5,12]. Considering its ubiquitous expression, one would assume that brains of Pclogt/gt rats manifest additional phenotypes alongside those reported in the cerebellum. Indeed, comparable to PCH3 patients, Pclogt/gt rats have a thinner cerebral cortex and an overall loss of brain volume [14,18]. Intriguingly, we found additional phenotypes which have not been observed in PCH3 patients. For example, we saw a dramatically increased number of adult neural stem cells in the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the hippocampal dentate gyrus (Figure 2A). This was detected by staining brain sections of 3-month-old Pclowt/wt and Pclogt/gt animals with an antibody for Doublecortin (DCX), a marker for adult neuronal stem cells [27], and DAPI as a general cell marker. DCX-DAPI double positive cells in the SGZ were manually counted. Here, significantly more neuronal stem cells were present in the SGZ of Pclogt/gt brains compared to Pclowt/wt brains (Pclowt/wt: 91+/-14.35, n=4 independent experiments; Pclogt/gt: 175,7+/-18,46, n=3 independent experiments, p<0.014,) (Figures 2A, 2B). These data indicate that adult stem cell proliferation is enhanced due to the lack of Piccolo. Interestingly a recent study could show that increased neuronal stem cell proliferation in the hippocampus can compensate for the age dependent decline in neurogenesis, having a positive impact on learning and memory [28]. Therefore, it would be interesting to analyze learning and memory in old Pclogt/gt compared to Pclowt/wt rats in future studies.

The observed changes in hippocampal stem-cell number is surprising as it opens the question of how the loss of a presynaptic active zone protein could impact neuronal stem cell proliferation. Interestingly, the aforementioned RNAseq data also show a deregulation of the cholecystokinin (CCK) signaling pathway [19]. Furthermore, a recent study finds that the neuropeptide CCK supports proliferation of neural stem cells [29]. Altered CCK release in the dentate gyrus of Pclogt/gt hippocampi could in part explain the observed increased number of neuronal stem cells. Conceptually, as an active zone protein, Piccolo could play a role in the regulated release of neuropeptides from dense core vesicles in CCK-positive interneurons. Further studies are needed to test this hypothesis. Intriguingly, CCK-positive cell bodies are also present throughout the cerebellar granule cell layer and in brainstem areas which project both mossy and climbing fiber afferents [30]. This localization is concurrent with the core changes that we observe in Pclogt/gt cerebella, indicating an exciting avenue for future investigation into the role of neuropeptide secretion as a possible underlying mechanism.

Signaling pathways such as Wnt or CCK rely on two main mechanisms: effective secretion of signaling factors from vesicles such as dense core vesicles and localization and trafficking of receptors. Both principles require molecular processes such as membrane/vesicle or receptor trafficking. Indeed, we recently demonstrated that Piccolo contributes to efficient synaptic vesicle trafficking [31]. Specifically, we observed that loss of Piccolo disrupts the formation of early endosomes via the impaired recruitment of Pra1 to presynaptic active zones [31]. Moreover, Zhang and colleagues revealed that Piccolo is involved in membrane trafficking events in non-neuronal cells, where it interacts with the EGFR pathway [32]. Both studies indicate that Piccolo can indeed regulate membrane trafficking events. Thus, Piccolo may well play an in/direct role in a number of other signaling pathways; an activity that likely depends on its tissue and subcellular distribution. During development, Piccolo is highly expressed in lamellipodia and growth cones of migrating and differentiating neurons, where it is thought to regulate the actin cytoskeleton in response to Wnt signaling (Figure 1). Alternatively, in mature neurons, it may affect the secretion of hormone and/or neurotransmitter substances such as CCK influencing other cellular signaling programs such as adult neurogenesis (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Loss of Piccolo leads to increased neuronal stem cell proliferation.

(A) Immunohistological stainings were performed on 20 μm thick cryosections of 3-month-old Pclowt/wt and Pclogt/gt brains. Especially the region of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus was analyzed. Antibodies against doublecortin were used as marker for adult neuronal stem cells [27]. DAPI was used to tag all cells present in the dentate gyrus area. Interestingly Pclogt/gt hippocampi display an increased number of doubelcortin/DAPI positive cells compared to Pclowt/wt hippocampi.

(B) Quantification of DCX/DAPI positive cells in sections of the dentate gyrus. Pclogt/gt sections exhibit significantly more DCX/DAPI positive cells compared to Pclowt/wt (Pclowt/wt: 91+/-14.35, n=4 independent experiments; Pclogt/gt: 175,7+/-18,46, n=3 independent experiments, students-t-test,p<0.014).

Importantly, Piccolo expression is not restricted to the brain, but can be observed in other tissues of the body such as the gut, liver, pancreas and the male and female reproductive system [12]. Piccolo’s function outside of the brain has not been extensively studied; however, it has been described as having a role in the secretion of insulin from pancreatic β-cells [21]. Again, Piccolo is proposed to be involved in regulating membrane trafficking events and thus the exocytosis/secretion of insulin from insulin-containing granules [21]. Medrano et al. [19] found genes involved in hormonal secretion pathways and in particular the GnRH signaling pathway to be significantly altered in the Piccolo knockout model. Again, membrane trafficking and or vesicle secretion seems a possible underlying mechanism for the observed phenotypes.

To summarize, Piccolo is a large multi-domain scaffold protein that can exist as alternatively spliced isoforms, some of which are highly concentrated at sites of neurotransmitter release and peptide secretion as well as structures that depend on the dynamic assembly of the actin cytoskeleton and the recycling of receptors, integral membrane proteins and the extracellular matrix. It is thus not surprising that its inactivation could cause a wide range of phenotypes, as seen both in Pclogt/gt rats and individuals with PCH3. As yet, there is still a depth of knowledge to be gleaned in this field, particularly with regard to Piccolo’s function outside of the presynaptic active zone. There are interesting open questions to answer: Firstly, is there a common cellular mechanism underlying the different phenotypes such as fewer granule cells, altered mossy fiber synapses, and increased neuronal stem cell numbers that we observe? Secondly, how is Piccolo involved in other diseases such as major depressive disorder or cancer?

Further elucidation of these questions could lead to effective treatments for a number of psychiatric and peripheral diseases.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Anny Kretschmer for technical assistance. The work was funded by Deutsches Zentrum für Neurodegenerative Erkrankungen (DZNE), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) SFB958 and Germany´s Excellence Strategy–EXC-2049-390688087.

References

2. Südhof TC. The synaptic vesicle cycle neurotransmitter release and the synaptic vesicle cycle. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004.

3. Gundelfinger ED, Reissner C, Garner CC. Role of bassoon and piccolo in assembly and molecular organization of the active zone. Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience. 2016 Jan 12; 7:19.

4. Kim E, Sheng M. PDZ domain proteins of synapses. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2004 Oct;5(10):771-81.

5. Cases-Langhoff C, Voss B, Garner AM, Appeltauer U, Takei K, Kindler S, et al. Piccolo, a novel 420 kDa protein associated with the presynaptic cytomatrix. European Journal of Cell Biology. 1996 Mar 1;69(3):214-23.

6. Fenster SD, Chung WJ, Zhai R, Cases-Langhoff C, Voss B, Garner AM, et al. Piccolo, a presynaptic zinc finger protein structurally related to bassoon. Neuron. 2000 Jan 1;25(1):203-14.

7. Shapira M, Zhai RG, Dresbach T, Bresler T, Torres VI, Gundelfinger ED, et al. Unitary assembly of presynaptic active zones from Piccolo-Bassoon transport vesicles. Neuron. 2003 Apr 24;38(2):237-52.

8. Zhai R, Olias G, Chung WJ, Lester RA, Dieck S, Langnaese K, et al. Temporal appearance of the presynaptic cytomatrix protein bassoon during synaptogenesis. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2000 May 1;15(5):417-28.

9. Fenster SD, Garner CC. Gene structure and genetic localization of the PCLO gene encoding the presynaptic active zone protein Piccolo. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2002 Jun 1;20(3-5):161-71.

10. Nishimune H, Badawi Y, Mori S, Shigemoto K. Dual-color STED microscopy reveals a sandwich structure of Bassoon and Piccolo in active zones of adult and aged mice. Scientific Reports. 2016 Jun 20;6(1):1-2.

11. Tokoro T, Higa S, Deguchi-Tawarada M, Inoue E, Kitajima I, Ohtsuka T. Localization of the active zone proteins CAST, ELKS, and Piccolo at neuromuscular junctions. Neuroreport. 2007 Mar 5;18(4):313-6.

12. Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, et al. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015 Jan 23;347(6220).

13. Wagh D, Terry-Lorenzo R, Waites CL, Leal-Ortiz SA, Maas C, Reimer RJ, et al. Piccolo directs activity dependent F-actin assembly from presynaptic active zones via Daam1. PLoS One. 2015 Apr 21;10(4):e0120093.

14. Ahmed MY, Chioza BA, Rajab A, Schmitz-Abe K, Al-Khayat A, Al-Turki S, et al. Loss of PCLO function underlies pontocerebellar hypoplasia type III. Neurology. 2015 Apr 28;84(17):1745-50.

15. Sullivan PF, de Geus EJ, Willemsen G, James MR, Smit JH, Zandbelt T, et al. Genome-wide association for major depressive disorder: a possible role for the presynaptic protein piccolo. Molecular Psychiatry. 2009 Apr;14(4):359-75.

16. Namavar Y, Barth PG, Kasher PR, Van Ruissen F, Brockmann K, Bernert G, et al. Clinical, neuroradiological and genetic findings in pontocerebellar hypoplasia. Brain. 2011 Jan 1;134(1):143-56.

17. Rajab A, Mochida GH, Hill A, Ganesh V, Bodell A, Riaz A, et al. A novel form of pontocerebellar hypoplasia maps to chromosome 7q11-21. Neurology. 2003 May 27;60(10):1664-7.

18. Falck J, Bruns C, Hoffmann-Conaway S, Straub I, Plautz EJ, Orlando M, et al. Loss of Piccolo function in rats induces cerebellar network dysfunction and Pontocerebellar Hypoplasia type 3-like phenotypes. Journal of Neuroscience. 2020 Apr 1;40(14):2943-59.

19. Medrano GA, Singh M, Plautz EJ, Good LB, Chapman KM, Chaudhary J, et al. Mutant screen for reproduction unveils depression-associated Piccolo’s control over reproductive behavior. BioRxiv. 2020 Jan 1:405985.

20. Rudnik‐Schöneborn S, Barth PG, Zerres K. Pontocerebellar hypoplasia. In: American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics 2014 Jun (Vol. 166, No. 2, pp. 173-183).

21. Fujimoto K, Shibasaki T, Yokoi N, Kashima Y, Matsumoto M, Sasaki T, et al. Piccolo, a Ca2+ sensor in pancreatic β-cells: involvement of cAMP-GEFII· Rim2· Piccolo complex in cAMP-dependent exocytosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002 Dec 27;277(52):50497-502.

22. Ahmad-Annuar A, Ciani L, Simeonidis I, Herreros J, Fredj NB, Rosso SB, et al. Signaling across the synapse: a role for Wnt and Dishevelled in presynaptic assembly and neurotransmitter release. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2006 Jul 3;174(1):127-39.

23. Hall AC, Lucas FR, Salinas PC. Axonal remodeling and synaptic differentiation in the cerebellum is regulated by WNT-7a signaling. Cell. 2000 Mar 3;100(5):525-35.

24. Kalinovsky A, Boukhtouche F, Blazeski R, Bornmann C, Suzuki N, Mason CA, et al. Development of axon-target specificity of ponto-cerebellar afferents. PLoS Biol. 2011 Feb 8;9(2):e1001013.

25. Aigner L, Caroni P. Absence of persistent spreading, branching, and adhesion in GAP-43-depleted growth cones. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1995 Feb 15;128(4):647-60.

26. Keller R. Shaping the vertebrate body plan by polarized embryonic cell movements. Science. 2002 Dec 6;298(5600):1950-4.

27. Brown JP, Couillard‐Després S, Cooper‐Kuhn CM, Winkler J, Aigner L, Kuhn HG. Transient expression of doublecortin during adult neurogenesis. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2003 Dec 1;467(1):1-0.

28. Berdugo-Vega G, Arias-Gil G, López-Fernández A, Artegiani B, Wasielewska JM, Lee CC, et al. Increasing neurogenesis refines hippocampal activity rejuvenating navigational learning strategies and contextual memory throughout life. Nature Communications. 2020 Jan 9;11(1):1-2.

29. Asrican B, Wooten J, Li YD, Quintanilla L, Zhang F, Wander C, et al. Neuropeptides Modulate Local Astrocytes to Regulate Adult Hippocampal Neural Stem Cells. Neuron. 2020 Oct 28;108(2):349-66.

30. King JS, Bishop GA. Distribution and brainstem origin of cholecystokinin‐like immunoreactivity in the opossum cerebellum. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1990 Aug 15;298(3):373-84.

31. Ackermann F, Schink KO, Bruns C, Izsvák Z, Hamra FK, Rosenmund C, et al. Critical role for Piccolo in synaptic vesicle retrieval. Elife. 2019 May 10;8:e46629.

32. Zhang W, Hong R, Xue L, Ou Y, Liu X, Zhao Z, et al. Piccolo mediates EGFR signaling and acts as a prognostic biomarker in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2017 Jul;36(27):3890-902.