Abstract

Objectives: This controlled cross-sectional study investigated the prevalence of different types of parentification in women with fibromyalgia (FM) compared to women with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), healthy controls (HC) and women with depression or anxiety disorder (AD). The study also examined associations with maladaptive interpersonal styles (subjugation, approval seeking, self-sacrifice).

Method: Validated self-report questionnaires were completed by 202 female FM patients, 51 women with RA, 41 with AD and 119 HC.

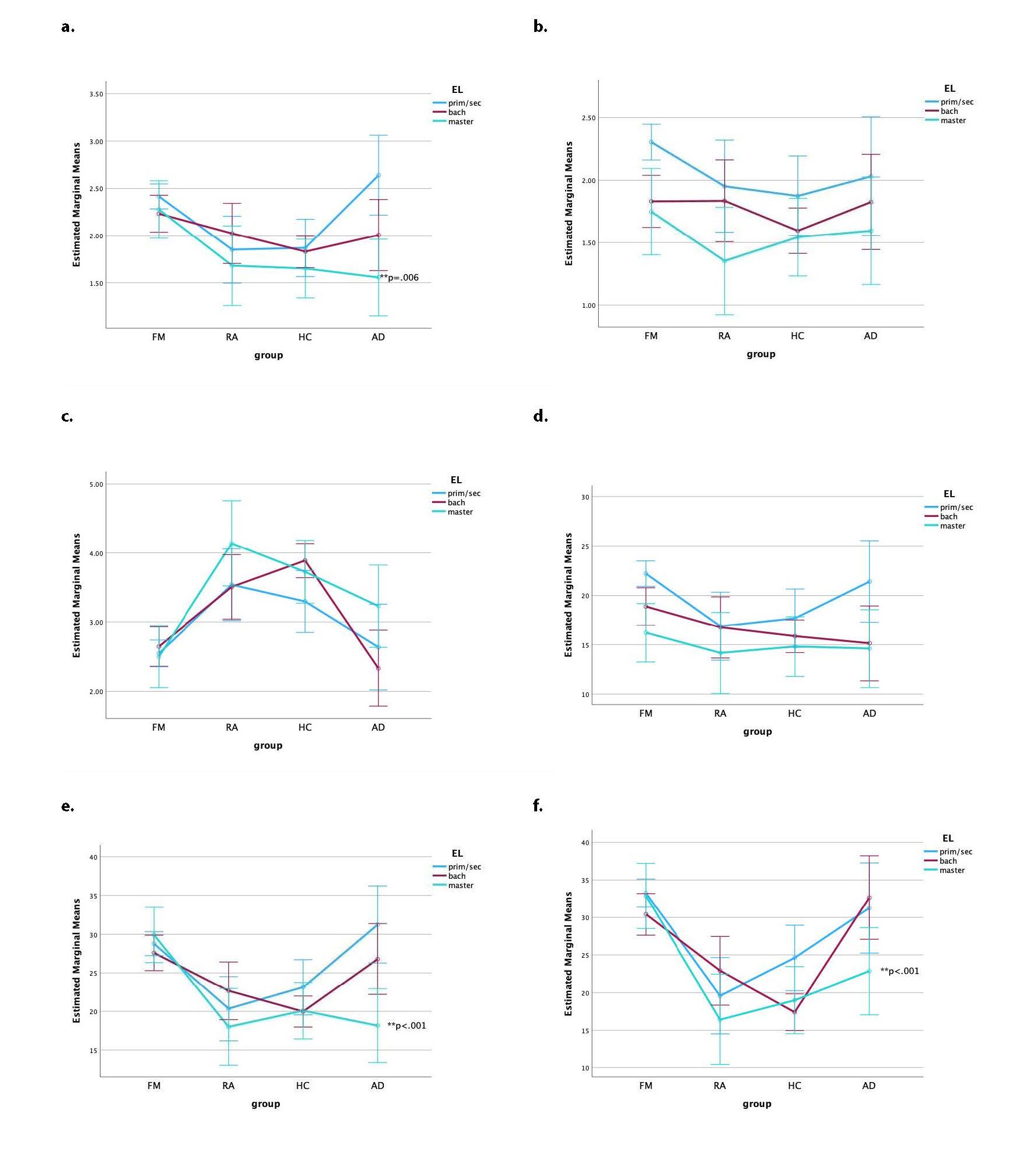

Results: Women with FM reported significantly higher levels of all parentification variables compared to the RA and HC groups but not compared to the AD group. An interaction effect with educational level was observed: among participants with Master's degree, some parentification scores (specifically unfairness, parent focused and emotional caregiving) were more pronounced in the FM group than in the AD group. Significant correlations were also found between parentification and maladaptive interpersonal styles.

Conclusions: These findings confirm a higher prevalence of fibromyalgia, depression, and anxiety disorder among women with parentification, as well as a link with maladaptive interpersonal styles. Educational level appears to play a moderating role, but these interactions should further be examined in larger groups. The results underscore the importance of a personalized biopsychosocial approach in fibromyalgia alongside standard therapy and highlight the value of early identification of risk factors.

Keywords

Fibromyalgia, Parentification, Subjugation, Approval seeking, Self-sacrifice

Introduction

Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a chronic pain syndrome that is often referred to as a ‘functional somatic syndrome’ in which psychological factors are believed to play an important role [1–3]. According to the most recent criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), the main symptom is unexplained widespread pain for at least 3 months; associated symptoms include fatigue, impaired concentration, non-restorative sleep, stimulus intolerance, post-exertional malaise, and various complaints related to neuro-vegetative dysfunction [4,5]. In clinical practice, there is an important symptomatic overlap with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), and frequent comorbidity with affective disorders and other functional somatic syndromes [6]. The prevalence of FM in Western Europe is estimated to be between 3 and 6 percent, with a male/female ratio of 1/4 to 1/7 [7,8].

Although the underlying pathophysiology of FM is still unclear, clinical experience as well as scientific research make it plausible that the stress system, and particularly the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis may play a key role in the syndrome [6]. More particularly, there are indications that too long and/or intense an activation of this axis may over time ‘turn over’ into a hypoactive state, resulting in a loss of resilience of the system. Hence, it is thought that, due to its central function in energy regulation and pain perception, a failure of the stress system may contribute to the onset and/or maintenance of the FM symptom complex [2,6].

Severe childhood stress may increase vulnerability for these pathophysiological changes and the correlation with childhood trauma is well established [9,10]. Although causal inferences are difficult to make, it is hypothesized that trauma and early-life stress can have a direct damaging impact on the development of the HPA-axis [11]. At the same time, early-life trauma has also been shown to foster defensive strategies that may develop into maladaptive personality traits [12]. The relative impact and interplay of these pathways remain to be clarified.

In a previous study we examined maladaptive interpersonal styles as defined in the “other- directedness” cluster of Young’s schemas and found that subjugation, approval-seeking, and self-sacrifice were significantly more prevalent in women with FM compared to those with rheumatoid arthritis [13]. Although the cross-sectional design does not allow for causal conclusions, these findings suggest that excessive “other directedness” may co-determine the course, therapeutic outcome and prognosis of FM. These maladaptive styles are often, though not exclusively, associated with childhood trauma and are more frequently observed in the context of a trauma subtype that remains understudied in fibromyalgia, namely “parentification” [14].

Parentification

Parentification is a form of role reversal in which a child takes on responsibilities typically associated with a parent, often to meet the emotional or practical needs of their caregiver. This can involve managing household tasks (instrumental parentification), caring for siblings, or providing emotional support to a parent (emotional parentification), usually in response to dysfunction, neglect, or trauma within the family system [15].

In 1967 Minuchin referred to “parental children” as assuming responsibilities beyond their developmental stage, often at the cost of their own emotional needs with potentially deleterious effects, the impact depending upon the temporary nature of the role reversal and the measure in which the child is being supported by the parents [16]. This phenomenon has also been studied in adult children of alcoholic parents [17].

John Bowlby (1973) and attachment theorists place emphasis on parentification as a way of organizing dyadic relations with an attachment figure in the service of establishing a sense of connection and security [18,19]. Parentification is often an adaptive strategy within an insecure attachment relationship: the child learns that it only receives love or attention by caring for the parent.

Boszormenyi-Nagy and colleagues observed that children often sacrifice their own developmental needs in order to meet the physical and/or emotional needs of the parents [20]. This can give rise to early competences such as resilience and adaptive coping, as well as responsibility, enhanced empathy and altruism, provided that parentification is transient or, if prolonged, the child is recognized and supported by its parents [21]. But often it reflects childhood deprivation resulting in the child being overburdened, not recognized or seen, and lacking space for their own development [22,23]. This contributes to the development of dysfunctional internal working models of both self -and other -representations often resulting in impaired relationships later in life. Individuals may lose the capacity to express their own needs or seek care, while retaining a deep unfulfilled longing for nurturance. Rather than fostering reciprocal relationships, these patterns tend to reinforce compulsive caregiving and the suppression of care-seeking behaviors [14]. Parentified children often become adept at anticipating the needs of others as their primary way of relating. These scripts are often continued in adulthood orienting them to helping professions [24,25].

They are also a risk factor for poor parenting and thus represent a transgenerational jeopardy [26,27].

Byng-Hall makes a distinction between adaptive and maladaptive parentification [23]. Maladaptive or destructive forms include excessive and developmentally inappropriate—instrumental and especially emotional—caregiver tasks that strongly determine identity.

Instrumental caregiving refers to children’s responsibilities for concrete functions supporting the family such as doing the chores or taking up school tasks with siblings. It is less consistently linked with negative outcomes and can harness favorable self-esteem [20]. On the other hand, emotional caregiving can encompass mediating family conflict as a peacekeeper, supporting a depressed parent, acting as a protector or confidante, saving an alcoholic parent from all kinds of dangers... [28,29]. Even low to moderate levels of emotional caregiving are considered detrimental [20,30]. These children internalize ongoing expectations to care, prioritize others’ needs and become alienated from their own needs; the energy that this requires limits the fulfilment of other developmental tasks [31].

Perceived benefits (as measured by the Hooper Parentification Inventory) seem to serve as a protective factor [32]. Parentification is especially harmful when it calls for tasks beyond the developmental abilities and adequate support is not forthcoming; especially perceived unfairness was found to be related to depressive symptoms in college students [33] and to negative self-esteem and lower parenting efficacy in parentified mothers [34].

According to Jurkovic destructive parentification should be classified as a separate form of emotional abuse [35]. Although childhood trauma has been repeatedly reported in fibromyalgia, it is mostly assessed using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, which does not explicitly measure parentification dimensions [10].

Common sources of role reversal include parental addiction, HIV, parental loss (divorce, migration, death, incarceration) or parental mental disability [36].

Previous research shows a higher incidence of depression, anxiety, social isolation, lower educational attainment, unemployment and poor physical health following emotional parentification [36–40]. These problems often obscure the caring role, reason why parentification is often missed. Parentification was associated prospectively with somatic symptoms and disturbance in interpersonal relations [41]. One retrospective study found an association between parentification and somatoform or somatization disorder with predominant pain symptoms [42]. However, to our knowledge, fibromyalgia as such has not yet been studied from a parentification perspective.

Qualitative studies also highlight suboptimal coping strategies such as self-sacrifice and reluctance to share the burden of stressors [36].

A range of factors can influence whether parentification leads to pathology or positive outcomes.

In general, girls seem to be at higher risk for parentification [37].

As to sibling order, first and second born children (especially daughters) are more likely to be expected to help with household tasks and sibling care [21], while only children are particularly vulnerable to taking on emotional caregiving roles for a parent [43].

Both the age at which parentification occurs and the duration of caregiving are associated with higher depressive symptom scores in adulthood [33].

Furthermore, cultural context plays a significant role. In western countries reportedly 2 to 8 percent of youth aged under 18 show some form of parentification [43]. Among children living in urban poverty moderate levels of instrumental and sibling focused, and to a lesser extent emotional parentification appear to be the norm [43]. Notably, one study involving African American youth failed to find any association between parentification and psychopathology [44].

Identifying parentification is important because it has therapeutic implications. The primary goal is to make sure that no parent needs to turn to a child for care by increasing the security of the family base and the availability of mutual support between adults and broader networks [23]. Finally, transgenerational effects have been evaluated by several authors [45,46]. Such transmission is theorized to be set in motion by parenting scripts that can either be replicative or corrective, the latter often equally dysfunctional since they were scripted from the past rather than adapted to the present context [23].

Hypotheses examined in this study

The primary objective of this study was to determine whether Belgian women with FM report higher levels of parentification compared to healthy controls (HC) and those with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). We hypothesized they would and more so on unfairness and on emotional than on instrumental caregiving. Additionally, we expected parentification scores of FM patients to be similar to those of women with a depressive or anxiety disorder (AD).

A secondary goal was to explore whether differences in parentification between FM and the control groups are moderated by educational level or sibling order (e.g., whether younger siblings report a lower caregiving burden than older siblings).

Finally, we hypothesized a correlation between parentification and maladaptive interpersonal patterns, specifically subjugation, self-sacrifice and approval seeking.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Patients with a diagnosis of FM according to ACR criteria (N=202) were recruited from the outpatient clinic of a general hospital (St. Maarten, Mechelen, Belgium) by a specialist in physical medicine and rehabilitation with 30 years of clinical experience with FM. The hospital also offers a multidisciplinary semi-residential therapy exclusively aimed at this patient group. To minimize selection bias, patients were included at their initial consultation with the diagnosing clinician rather than upon referral to the therapy unit, thereby reducing the likelihood of overrepresenting individuals with specific psychological characteristics.

Patients in the first control group (N=51) all had a diagnosis of RA. We chose this condition because of its similar symptoms of pain and fatigue. These patients were recruited by rheumatologists at the outpatient clinic of a university hospital, two general hospitals and four private practices in the provinces of Antwerp, East Flanders, and Limburg.

Participants in the second control group (N=119) had neither of these diagnoses and were recruited by several general practitioners and by the principal investigator from the pool of employees in the general hospital (HC).

For these 3 groups, psychiatric problems (as defined by DSM 5 criteria) that were prominent at the time of screening and required active treatment, were exclusion criteria.

Finally group 4 (N=41) consisted of patients being treated for anxiety disorder and/or depressive disorder (AD). They were recruited from a psychiatric hospital, a general hospital, a day care center, and a private psychiatric practice.

For all groups, the inclusion criteria were voluntary participation, female gender, and age between 25 and 60 years. Individuals with a diagnosed psychoactive substance use disorder (according to DSM-5 criteria) or intellectual impairment were excluded. The use of pain medication or antidepressants was allowed.

All participants were assessed for inclusion in order of presentation. They were provided with an informed consent form, explaining the purpose and design of the study. All assessment measures were self-report questionnaires. Participants were also asked to complete a form with personal data: age, gender, type of education, marital status, profession, and order in the sibling of the parental family. For the FM and RA group the duration of the complaints was registered. Participants were asked to return the completed forms in a sealed envelope or bring them to their next appointment.

Prior to recruitment, the physicians received detailed information from the researcher regarding the inclusion criteria, study design, and procedures to be followed. The study was conducted according to ICH-GCP E6R2 guidelines and approved by two ethics committees of the participating hospitals (Emmaus and UZA). It was registered at https://be.edge-clinical.org with trial number EDGE 001796.

Assessment

Parentification was measured by two scales, the Parentification Inventory (PI) and the Filial Responsibility Scale-Adult (FRS-a).

The PI (Hooper, 2009) is a retrospective 22-item self-report questionnaire with responses on a 5-point scale and consisting of three subscales: parent-focused parentification (PF), sibling-focused parentification (SF) and perceived benefits (PB) [47]. We used the Dutch translation (translation/backtranslation by Doyle A and Maes F, 2020, unpublished). The original PI has been validated with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of .85 for PF, .82 for SF and .76 for PB [48].

The FRS-a (Jurkovic and Thirkield, 2001) is a self-report questionnaire assessing instrumental caregiving (IC), emotional caregiving (EC), and unfairness (UNF) from two temporal perspectives: retrospective and current [49]. Each scale contains 10 items, to be scored on a 5-point scale. For our purpose we used the Dutch translation (translation/ backtranslation by Van Parys H, Baitar R & Hooghe A, 2008 unpublished). Only the retrospective measures were further analyzed. The original scale has been validated with good internal consistency Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of .92 and of .74, .79, and .86 for the respective subscales [34,49].

The Young Schema Questionnaire (YSQ-L3) is a self-report questionnaire containing 16 early maladaptive schemes [50]. We used the 3 schemas in the domain of “other-directedness”, namely “subjugation” (SJ-10 items), “approval-seeking” (AS-14 items), and “self-sacrifice” (SS-17 items), scored on a 6-point scale. The psychometric properties of this questionnaire, as well as those of the Dutch translation, have been rated as good in several studies, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from .92 to .96 [50–53].

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was administered to the FM patients. This self-report questionnaire contains 2x7 items, scored on a 4-point scale (0–3) and divided in 2 subscales: anxiety and depression [54]. Scores between 8 and 11 indicate a possible, and scores between 11 and 21 a probable depression and/or anxiety disorder. The scale has been widely used and validated in physically ill populations including patients with FM [55]. Both the original and Dutch versions have demonstrated adequate validity [56,57].

Statistical procedure

Preliminary sample size calculation was performed with G*Power. We opted for a type I error alpha = .05. We wanted a statistical power of .90 for a one-way ANOVA comparing the 4 diagnostic groups, requiring 60 participants per group for a moderate effect size f of .25, corresponding to an R2 slightly below .06.

An occasional missing value (1 percent) was handled by imputation, in which case the subscale was calculated by the mean of the non-missing values.

All reported p-values are two-tailed.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Statistics Version 29.0.2.0.

The STROBE guidelines for reporting cross-sectional studies were followed.

Results

Characteristics of the patient groups

After excluding 3 RA, 2 FM, and 1 AD cases due to incomplete questionnaires, the final sample consisted of 202 women with FM, 51 with RA, 41 with AD, and 119 HC. Demographic data were missing for 1 RA patient. In the FM group 3 patients did not report their residential status. These patients were included in all analyses except those examining interactions with residential status.

The duration of symptoms in the FM group ranged from 6 to 300 months, with a mean of 91.6 and a median of 72 months. This was similar to the RA group where symptom duration ranged from 8 to 270 months, with a mean of 96.64 and a median of 70 months.

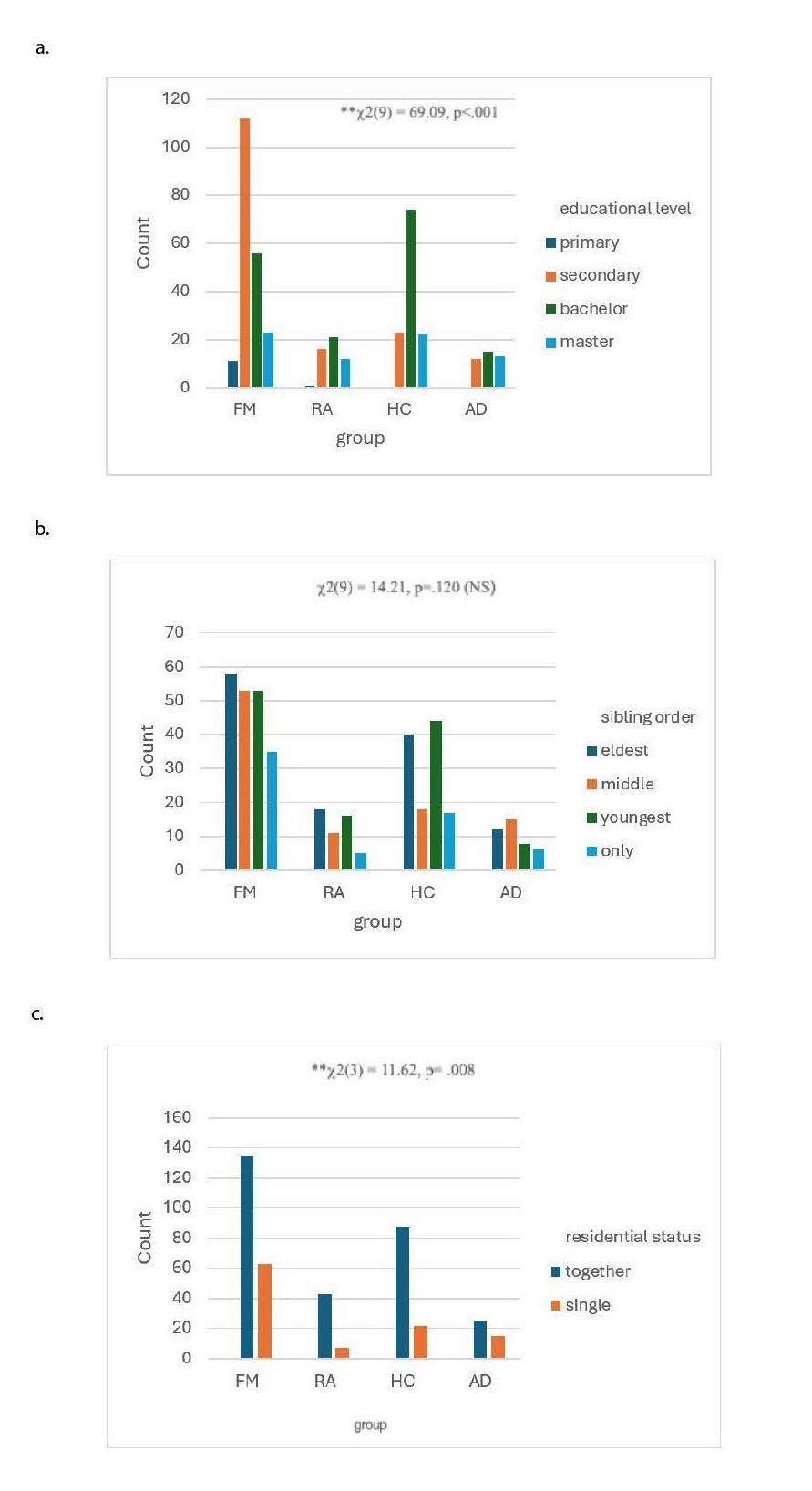

Sociodemographic characteristics are displayed in Table 1 and visualized in Figure1.

|

|

|

Total (N= 413) |

FM (N=202) |

RA* (N=51) |

HC (N=119) |

AD (N=41) |

|

Age (average) |

|

43.06 |

42.18 |

43.92 |

44.65 |

41.73 |

|

Age (range) |

|

18–63 |

18–63 |

20–55 |

25–60 |

20–56 |

|

Residential status |

Living together |

291 (73.1%) |

135 (68.2%) |

43 (86.0%) |

88 (80.0%) |

25 (62.5%) |

|

Single |

107 (26.9%) |

63 (31.8%) |

7 (14.0%) |

22 (20.0%) |

15 (37.5%) |

|

|

Educational level |

Primary |

12 (2.9%) |

11 (5.4%) |

1 (2.0%) |

0 |

0 |

|

Secondary |

163 (39.7%) |

112 (55,4%) |

16 (32.0%) |

23 (19.3%) |

12 (30%) |

|

|

Bachelor |

166 (40.4%) |

56 (27.7%) |

21 (42.0%) |

74 (62.2%) |

15 (37.5%) |

|

|

Master |

70 (17.0%) |

23 (11.4%) |

12 (24%) |

22 (18.5%) |

13 (32.5%) |

|

|

Sibling order in family of origin |

Eldest |

128 (31.3%) |

58 (29.1%) |

18 (36.0%) |

40 (33.6%) |

12 (29.3%) |

|

Middle |

97 (23.7%) |

53 (26.6%) |

11 (22.0%) |

18 (15.1%) |

15 (36.6%) |

|

|

Youngest |

121 (29.6%) |

53 (26.6%) |

16 (32.0%) |

44 (37.0%) |

8 (19.5%) |

|

|

Only child |

63 (15.4%) |

35 (17.6%) |

5 (10.0%) |

17 (14.3%) |

6 (14.6%) |

|

|

*Missing demographic data; 1 (RA) |

||||||

Figure 1. Distribution of sociodemographics in the 4 diagnostic groups (Tables 1 and 2). Clustered Bar Counts. (a) By educational level (EL), (b) by sibling order (SO); (c) by residential status (RES).

There was a notable imbalance in educational attainment across the groups, with women with fibromyalgia being overrepresented in the lower education categories (primary and secondary education). The Pearson Chi Square test showed a highly significant difference ( c2 (9) = 69.09, p<.001. Cramer’s V = .237) indicating a moderate effect size (Table 2). For residential status c2 (3) = 11.62, p= .008 with Cramer’s V= .171 and for sibling order c2 (9) = 14.21, p=.120 with a low effect size Cramer’s V= .108.

|

|

Educational level |

Sibling order |

Residential status |

|

Pearson chi square |

69.09 |

14.21 |

11.62 |

|

Cramer’s V |

.237 |

.108 |

.171 |

|

p |

<.001 |

.120 |

.008 |

We checked for normality for all variables by inspection of histograms for shape (kurtosis and skewness) and outliers. For IC, PF, and SF nearly all distributions did not meet requirements for normality. Non-parametric bootstrapping was applied for all tests. When the assumption of equal variances was violated, robust tests of equality of means (Welch) were used.

Validation of translated questionnaires

We validated the Dutch translation of both parentification questionnaires in our sample. The PI subscales showed Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of .87 (PF), .80(SF), and .90 (PB). For the FRS-a scale, Cronbach's alpha was .95, with subscales scoring .86 (IC), .90 (EC), and .95 (UNF).

Main effects

We ran the ANOVA procedure for the main effects of the 4 diagnostic group (Table 3) and found highly significant differences between diagnostic groups for all parentification variables. We report the Welch F’s.

For PF F=16.20 (3, 123.10), p<.001 and w2=.146

For SF F=11.04 (3, 128.70, p<.001 and w2=.065

For PB F=38.52 (3, 120.45), p<.001 and w2=.200

For IC F=11.97 (3, 126.98), p<.001 and w2=.074

For EC F=26.12 (3, 122.22), p<.001 and w2=.147

For UNF F=47.45 (3, 118.96), p<.001 and w2=.244

|

Mean (SD) |

||||||||

|

Parentification variable |

|

global (N=413) |

FM (N=202)* |

RA (N=51) |

HC (N=119) |

AD (N=41) |

Welch test p |

Omega squared (95% CI) |

|

HPI |

PF |

2.10 (.79) |

2.35 (.85) |

1.87 (.09) |

1.80 (.05) |

2.05( .12) |

<.001 |

.094 (.041-.146) |

|

SF |

1.84 (.75) |

2.05 (.86) |

1.74 (.64) |

1.59 (.54) |

1.77 (.57) |

<.001 |

.065 (.020-.114) |

|

|

PB |

3.06 (1.22) |

2.57 (1.78) |

3.66 (1.11) |

3.75 (.90) |

2.72 (1.16) |

<.001 |

.200 (.131-.262) |

|

|

FRS-a |

IC |

18.39 (7.70) |

20.61 (8.65) |

16.16 (5.91) |

16.03 (5.82) |

17.05 (6.44) |

<.001 |

.074 (.026-.124) |

|

EC |

25.00 (9.60) |

28.58 (9.60) |

20.71 (7.37) |

20.61 (7.80) |

25.38 (9.61) |

<.001 |

.147(.084-.207) |

|

|

Unf |

26.76 (12.36) |

32.42 (11.24) |

20.35 (10.50) |

19.11 (9.60) |

28.93 (11.63) |

<.001 |

.244 (.171-.307) |

|

|

For SF; only children were omitted. N =346 (FM =164/ RA= 45/HC=102/AD=35) |

||||||||

In the Post Hoc procedure (Table 4), we applied the Games Howell test since for most variables the assumption of equal variances was violated. Of note, since we only compared the FM group to the 3 control groups and Games Howell considers 6 comparisons, ps were systematically overestimated. Pairwise comparisons were also tested by means of non-parametric bootstrapping (1000 samples) with the CI set at 98.4% as a correction for 3 comparisons. This adjustment of interval width is equivalent to a Dunn-Sidak correction for 3 tests, thus keeping the family-wise error rate at (a maximum of) 5%.

|

Parentification variable |

Comparison group |

Mean difference |

p |

Bootstrap 95% CI * |

||

|

HPI |

PF |

RA |

.48 |

<.001 |

.19 |

.73 |

|

HC |

.55 |

<.001 |

.35 |

.74 |

||

|

AD |

.30 |

.099 |

-.05 |

.62 |

||

|

SF |

RA |

.36 |

.006 |

.05 |

.64 |

|

|

HC |

.48 |

<.001 |

.26 |

.69 |

||

|

AD |

.30 |

.033 |

.01 |

.59 |

||

|

PB |

RA |

-1.09 |

<.001 |

-1.51 |

-.64 |

|

|

HC |

-1.17 |

<.001 |

-1.47 |

-.90 |

||

|

AD |

-.15 |

1.00 |

-.64 |

.38 |

||

|

FRS-a |

IC |

RA |

4.45 |

<.001 |

1.79 |

6.72 |

|

HC |

4.58 |

<.001 |

2.52 |

6.58 |

||

|

AD |

3.56 |

.009 |

.49 |

6.31 |

||

|

EC |

RA |

7.88 |

<.001 |

4.71 |

10.76 |

|

|

HC |

7.97 |

<.001 |

5.52 |

10.23 |

||

|

AD |

3.20 |

.153 |

-.68 |

7.14 |

||

|

Unf |

RA |

12.06 |

<001 |

8.02 |

16.21 |

|

|

HC |

13.31 |

<.001 |

10.07 |

16.10 |

||

|

AD |

3.49 |

.234 |

-1.61 |

8.74 |

||

|

*Adjusted for multiplicity For SF; only children were omitted. N =346 (FM =164/ RA= 45/HC=102/AD=35) |

||||||

All 6 parentification variables showed consistently higher means in the FM group compared to the RA and HC group.

In comparison to the RA and HC groups, all differences in means were highly significant with p<.001 except SF in the comparison between FM and RA which was significant with p=.006.

In comparison to the AD group FM patients did not show a significant difference for PB, PF, EC and UNF. In comparison to the AD group, the FM group showed a higher score on IC (p= .009) and on SF (p=.033). These conclusions were consistent with inferences based on the bootstrap.

We controlled for residential status (Supplementary Table 1) and sibling order (Supplementary Table 2); for all parentification variables mean differences between the diagnostic groups remained significant (p<.001).

To explore the main effects of educational level, we ran an ANOVA procedure, lumping the groups of primary and secondary into “Prim/Sec” so that 3 levels were retained in the comparison: Prim/Sec, Bach and Master. The study identifies a highly significant imbalance in educational attainment (p<.001), with the FM group having a disproportionately high number of participants in the lower education categories, and educational level showing significant main effects on all parentification variables (Supplementary Table 3).

Although the effect of the diagnostic group remains significant after controlling for education (Supplementary Table 4), the primary comparison is structurally weak due to this baseline confounding.

In the Post Hoc procedure, we applied the Games Howell test since for most variables the assumption of equal variances was violated (Supplementary Table 5).

No significant differences were found between the Bach and Master groups.

For all parentification variables scores were higher in the Prim/Sec group, and (in keeping with this finding) lower for PB, with highly significant p values (ranging from .004 to <.001).

Interactions.

Performing factorial ANOVA, we found no significant interaction effects between diagnostic group and residential status for any of the parentification variables, nor between diagnostic group and sibling order.

However, we found significant interaction effects for the variables EC and UNF between diagnostic group and educational level with small effect sizes. For EC F (6,397) =2.71, p=.014, w2=.020. For UNF F (6,397) =2.31, p=.033, w2=.014.

These interactions are displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Interaction effects between diagnostic group and educational level. Estimated marginal Means of parentification subscales with 95% CI. (a) PF, (b) SF, (c) PB, (d) IC, (e) EC, (f) UNF.

To explore the data further we bootstrapped parameter estimates for the interaction effects between diagnostic group and educational level. All p-values and 95% CIs have been adjusted for multiplicity (Supplementary Table 6). To facilitate interpretation of the interaction effects and conditional differences between diagnostic groups, one should take into account that the diagnostic group dummy variables estimate the mean difference with the reference category FM for RA, HC, and AD. Since Master’s degree is the reference category for education level, these main effects are the estimated differences for participants with a Master’s degree while the interaction effects with primary/secondary education and Bachelor’s degree estimate to what extent the difference between the diagnostic group of interest and FM differs for these education levels in comparison to masters. Supplementary Table 6 displays all conditional differences for all education levels, which can be reconstructed from the main and interaction effects in this section.

For EC, the AD group scored significantly lower than FM among participants with a Master’s degree (b=- 11.76, 95% CI [- 18.75; - 5.22]. The significant interactions between education level and the AD dummy indicate that this difference is significantly weaker - to the extent of being virtually non-existent - for participants with only primary or secondary education (b=14.23, 95% CI [4.95; 23.97] and Bachelor’s degrees (b=11.00, 95% CI [0.06; 22.09]. Summing the main effect of AD with the respective education level, interaction effects yields the conditional differences between FM and AD for primary/secondary education and Bachelor’s degrees (Supplementary Table 6), both of which are non-significant (adjusted ps=1)

For UNF, no single interaction was significant but there was a marginally significant interaction between AD and Bachelor’s degree (b=12.26, p=.060, 95% CI [-.28; 25.26], suggesting that the difference between AD and FM for bachelors might be weaker in comparison to the difference found for masters (b=-10.02, 95% CI [- 17.92; -1.74].

Although the interaction effects for PF were unsignificant on the whole, we again found a difference between FM and AD for Masters (mean difference for Masters =.72, 95% CI [.17- 1.32]) with an significant interaction between AD and primary/secondary education indicating the difference between AD and FM to be weaker for this educational subgroup (b=.95, 95% CI [.14; 1.82]).

Looking at differences between the diagnostic groups (Supplementary Table 6) we consistently found significant differences in the bootstrap between FM and RA/HC regardless of educational level. The difference between FM and AD was significant only for Masters for PF (p=.006), UNF (p=<.001), and EC (p<.001).

HADS correlations.

We found no significant correlations between parentification variables and scores on the HADS (Table 5), exception made for a very modest correlation between SF and the depression score showing a Pearson r=.176, p=.026.

|

|

PF |

SF |

PB |

IC |

EC |

UNF |

|

|

HADS_a |

Pearson r |

-.067 |

.129 |

.057 |

.004 |

-.111 |

-.084 |

|

p-value (2-tailed) |

.353 |

.105 |

.425 |

.961 |

.122 |

.240 |

|

|

N |

197 |

159 |

197 |

196 |

197 |

197 |

|

|

HADS_d |

Pearson r |

-.008 |

.176* |

-.017 |

.119 |

-.063 |

-.051 |

|

p-value (2-tailed) |

.907 |

.026 |

.816 |

.098 |

.383 |

.478 |

|

|

N |

197 |

159 |

197 |

196 |

197 |

197 |

|

|

* Correlation significant with p<0.05 (2-sided). HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; a: Anxiety; d: Depression |

|||||||

YSQ-L3 correlations

YSQ scores were obtained from the FM, RA, and AD groups and checked for heteroscedasticity and normality for all variables by inspection of histograms, normal probability plots, outliers. Since the distributions were all normal, and the assumption of equal variances was not violated, we calculated Pearson r for correlation with the parentification variables (Table 6A). We found medium- size correlations between SS/SJ on the one hand and PB, EC, and especially UNF on the other hand, as well as between AS and UNF, all with p<.001. All other correlations were rather small-sized. IC showed the smallest r sizes, significant with SJ and SS, but insignificant with AS.

Since we found correlations between HADS scores and SS/SJ/AS (ranging from .188 to .320) in a previous study [13], we computed the same correlations for the FM group and controlled for HADS scores (anxiety and depression). We found a very similar pattern with slightly smaller r values (Table 6B). Highest correlations (p<.001) were always seen with the UNF scores and the r values with EC always exceeded those with IC.

|

6A. Cumulative group RA+AD+FM |

|||||||

|

|

|

PF |

SF |

PB |

IC |

EC |

UN |

|

Y-SJ |

Pearson r |

.262** |

.258** |

-.382** |

.190** |

.350** |

.445** |

|

95% CI |

.150–.366 |

.145–.365 |

-.477–-.279 |

.075–.299 |

.224–.448 |

.347–.533 |

|

|

P (2- tailed) |

<.001 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

.001 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

|

|

N |

287 |

278 |

287 |

286 |

287 |

287 |

|

|

Y-SS |

Pearson r |

.270** |

.282** |

-.325** |

.246** |

.326** |

.394** |

|

95% CI |

.159–.374 |

.170–.386 |

-.425–-.217 |

.134–.352 |

.218–.425 |

.292–.488 |

|

|

P (2- tailed) |

<.001 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

|

|

N |

287 |

278 |

287 |

286 |

287 |

287 |

|

|

Y-AS |

Pearson r |

.189** |

.150* |

-.280** |

.108 |

.268** |

.351** |

|

|

95% CI |

.074–.298 |

.033–264 |

-.384–-.169 |

-.008–.222 |

.156–.372 |

.245–.449 |

|

|

P (2- tailed) |

.001 |

.012 |

<.001 |

.069 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

|

|

N |

285 |

276 |

285 |

284 |

285 |

285 |

|

B. FM group, controlled for HADS-a and HADS-d |

|||||||

|

|

|

PF |

SF |

PB |

IC |

EC |

UN |

|

Y-SJ |

Pearson r |

.233** |

.255** |

-.356** |

.148* |

.329** |

.403** |

|

|

95% CI |

.087–.358 |

.139–.366 |

-.479–-.219 |

.021–.272 |

.192–.458 |

.284–.520 |

|

|

P (2-tailed) |

.001 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

.041 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

|

|

N |

195 |

186 |

195 |

194 |

194 |

194 |

|

Y-SS |

Pearson r |

.182* |

.280** |

-.295** |

.185* |

.233** |

.309** |

|

|

95% CI |

.049–.316 |

.151–.395 |

-.415–-.177 |

.059–.307 |

.111–.358 |

.180–.432 |

|

|

P (2-tailed) |

.011 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

.010 |

.001 |

<.001 |

|

|

N |

195 |

186 |

195 |

194 |

194 |

194 |

|

Y-AS |

Pearson r |

.178* |

.160* |

-.239** |

.107 |

.256** |

.311** |

|

|

95% CI |

.029–.317 |

.008–.292 |

-.459–-.198 |

-.034–.242 |

.125–.391 |

.178–.448 |

|

|

P (2-tailed) |

.013 |

.030 |

<.001 |

.140 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

|

|

N |

195 |

186 |

195 |

194 |

194 |

194 |

|

Y: YSQ-L3; SJ: Subjugation; SS: Self-Sacrifice; AS: Approval Seeking ** Correlation significant with p<0.01 (2-sided). * Correlation significant with p<0.05 (2-sided). |

|||||||

Discussion

Our study confirms a significantly higher rate of all parentification dimensions, as measured by the HPI and FRS-a, with the largest effect sizes for unfairness (mirrored by perceived benefits) and emotional caregiving, in the FM and AD groups in comparison to the HC and RA groups. The strength of the connection between reported parentification and diagnostic group is put in evidence by the fact that all differences remained significant after controlling for residential status, sibling order, and educational level.

Between the FM and AD groups we only found a significantly higher score on IC and SF, with smaller effect sizes. Interestingly, some factorial ANOVA models allowing the group differences to be moderated by educational level showed a significant interaction effect between these variables; FM patients with a Masters degree reported significantly higher scores on three parentification variables (PF, UNF, and EC) than their AD counterparts, while this was not the case for lower levels of education. This heterogeneity in FM-AD differences across educational levels was reflected in the significant AD- educational level interactions for EC, AD-Bachelor interaction for UNF and marginally significant AD-prim/sec education interaction for PF. Given the unequal group sizes and the relatively small AD group size, this finding should be interpretated with caution and requires further exploration in larger samples.

Although not the primary focus of this study, we observed significant correlations between all parentification variables and educational level, particularly among participants with only primary or secondary education compared to those who obtained a Bachelor’s or Master’s degree. This is in keeping with qualitative studies indicating that parentification is associated with compromised educational attainment, as represented by school dropout [36]. On the other hand, it should be kept in mind that parentification is more common in families experiencing poverty, where educational opportunities are also limited [42]. Additionally, most quantitative studies focus on college students, leaving early school leavers underrepresented [36].

A secondary finding was also that sibling order appeared to have an influence on some parentification scores. Not unexpectedly both oldest and middle siblings reported significantly higher scores on SF compared to youngest siblings. Youngest siblings reported lower perceived unfairness (reflected in lower UNF and higher PB scores) while middle siblings showed the opposite pattern. For IC middle siblings had the highest scores, significantly different from youngest or only children, but not from oldest siblings. These results are consistent with previous research and highlight the importance of examining parentification against the backdrop of other family characteristics [21].

No associations were found between residential status and parentification scores, except for PB and UNF, reflecting the fact that single participants reported more perceived past unfairness than those living together.

Depression and anxiety scores were only available for the largest diagnostic (FM) group. The lack of strong correlations between parentification scores and HADS scores suggests current mood did not strongly influence the retrospective self-report of parentification.

The hypothesis that parentification is associated with maladaptive interpersonal styles was confirmed, particularly for subjugation and self-sacrifice and to a lesser extent for approval seeking. The magnitude of the correlations observed in our study supports the multifactorial nature of these maladaptive interpersonal styles. The strongest correlations were found for UNF and EC, both with moderate effect sizes. For IC these effect sizes were small and even became unsignificant for approval seeking. These findings are in line with previous research indicating that IC may have less impact on future development [20]. This result further suggests that caregiving in an unsupportive, non-validating family environment (reflected by high UNF scores and low PB scores) may be more critical for the development of these interpersonal styles than the extent of caregiving itself. Similar associations have been reported between perceived unfairness and adult depressive symptoms [32,33].

Limitations of the study

First, the wide range in symptom duration may reflect not only differences in symptom severity and level of functioning but also variations in (inter)personal dynamics.

Second, as only female patients were included, it remains to be investigated whether male patients might report similar parentification histories.

Third, ethnicity was not controlled for. Several studies emphasize that effects of parentification can be moderated by cultural context and that parentification is more likely to result in negative consequences when caregiving is not considered the norm in a specific culture [38].

Fourth, the FM group contained a disproportionally high number of patients with lower educational level. This may reflect a genuine vulnerability to FM or a recruitment bias.

Furthermore, previous studies suggest that shorter periods of parentification may foster competence, whereas prolonged parentification can negatively impact psychosocial development [23,40]. Earlier age of onset and longer duration have been associated with depressive symptoms and greater problems of emotion regulation [40]. Our study gives us no insights into these aspects.

Also, there are limitations inherent in self-reporting. Participants’ recollections may be influenced by a desire for recognition of their suffering and negative outcomes such as anxiety disorder, depression or fibromyalgia could increase perceptions of unfairness or the recall of disproportionate caregiving.

Finally, besides limitations in terms of (causal) inference and design, it should also be taken into account that parentification, fibromyalgia and depression are multifactorial and complex, and conclusions should be drawn carefully. As is the case for most psychometric and diagnostic constructs, some ambiguity in measurement and cut-offs is inevitable and conclusions may differ between different scalar approximations or diagnostic criteria.

Conclusion

This controlled cross-sectional study demonstrates that, as a group, women with FM report significantly higher levels of parentification compared to women with RA and healthy controls.

When comparing the Omega squared point estimates, the effect sizes are most pronounced for UNF/PB, followed by EC and smallest for IC.

On the other hand, the parentification levels of the FM group were nearly identical to those in women with recent depressive or anxiety disorder. The most novel finding is the significant interaction between Diagnostic Group and Educational Level for EC and UNF, where FM patients with a Master’s degree report higher scores on these scales than their AD counterparts. This observation warrants further investigation in larger samples.

A clear association was found between parentification and maladaptive interpersonal patterns, particularly self-sacrifice and subjugation, especially in relation to EC and UNF.

The moderate correlations observed in this study further highlight the multifactorial nature of these patterns.

Given the persistent and severe symptom burden of FM, its substantial impact on professional and family functioning, its significant economic cost, and the lack of effective treatments, greater emphasis should be placed on preventive measures.

A high prevalence of early childhood trauma is consistently reported in FM but most of these studies use the CTQ, which does not adequately assess parentification. We recommend that parentification should systematically be screened for in cases of recurrent depression, anxiety disorder and fibromyalgia. Early identification, especially in children of a parent with chronic illness or a history of parentification, may contribute to preventive measures and counter transgenerational transmission.

Future research should focus on larger samples to get a better view on co-determining factors such as socio-economic status, ethnocultural environment, educational level and sibling order.

To account for region-specific differences in parentification a design with mixed models might be appropriate. Due to the markedly lower prevalence of fibromyalgia among men, sex differences could not be analyzed in this study; future research including male participants is recommended.

Since the present study is cross-sectional, it cannot make any statements about causation. Longitudinal research as well as the inclusion of control variables and causal inference tools such as propensity scores are needed to better understand the influence of different forms of parentification on type and course of illness in later life.

Future research could also elucidate along which pathways emotional parentification exerts its effect and which factors moderate between parentification and maladaptive interpersonal styles (attachment style, emotion regulation, HPA- axis- reactivity...).

Finally, we have to bear in mind that parentification is a multidimensional concept and that it should not only be defined by measurements of a child’s caregiving. There is still little literature contextualizing parentification into the broader frame of parenting competences and individual features of the child. Endeavors to take these co-determinants into account can shed further light on the pathways fostering resilience or leading to pathology and can also help avoid over-pathologization [38,58].

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Els Goossens for recruiting FM patients, Dr. Stijn Michiels, Prof. Dr. Jan Lenaerts, Dr. Anneleen Moeyersoons, Dr. Marc Walschot, Dr. Evelien De Boeck, and Dr. Jan Remans for recruiting RA patients; Dr. Carmen De Grave, Dr Esther Maris, and Dr Carla De Smedt for recruiting depressed and anxious patients; Dr jo Mertens, Dr Benny Maes, and the staff and participants of AZ St. Maarten for recruiting the healthy controls; Amber Maes and Ulysse Maes for the logistical support; Dr. Aileen Doyle and Prof. Hanna Van Parys for the translational work.

Study Approval

The authors declare that the study was conducted according to ICH-GCP E6R2 guidelines. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by “Ethisch comité UZA/UA”and “Commissie Ethiek-vzw Emmaüs” and registered at https://be.edge-clinical.org with trial number EDGE 001796.

Consent to Participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants in this study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Sources

No financial support was received for this study nor for this manuscript.

Author Contributions Statement

All authors contributed to this manuscript. F Maes, and G Vanaerschot conceived and designed the study. F Maes and colleagues collected the data. F Maes and J Berwouts performed the statistical analysis. F Maes, J Berwouts, and G Vanaerschot wrote and reviewed the paper.

Liability and Copyright

All authors hereby declare that they agree with the imposed rules regarding liability and copyright.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings in this study are available by simple request to the corresponding author at frankmaespsy@gmail.com.

References

2. Van Houdenhove B, Egle UT. Fibromyalgia: a stress disorder? Piecing the biopsychosocial puzzle together. Psychother Psychosom. 2004 Sep-Oct;73(5):267–75.

3. Malin K, Littlejohn GO. Psychological factors mediate key symptoms of fibromyalgia through their influence on stress. Clin Rheumatol. 2016 Sep;35(9):2353–7.

4. Galvez-Sánchez CM, Reyes Del Paso GA. Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia: Critical Review and Future Perspectives. J Clin Med. 2020 Apr 23;9(4):1219.

5. Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Häuser W, Katz RL, et al. 2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016 Dec;46(3):319–29.

6. Van Houdenhove B, Luyten P. Stress, depression and fibromyalgia. Acta Neurol Belg. 2006 Dec;106(4):149–56.

7. Wolfe F, Brähler E, Hinz A, Häuser W. Fibromyalgia prevalence, somatic symptom reporting, and the dimensionality of polysymptomatic distress: results from a survey of the general population. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013 May;65(5):777–85.

8. Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, Russell IJ, Hebert L. The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 1995 Jan;38(1):19–28.

9. Gardoki-Souto I, Redolar-Ripoll D, Fontana M, Hogg B, Castro MJ, Blanch JM, et al. Prevalence and Characterization of Psychological Trauma in Patients with Fibromyalgia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pain Res Manag. 2022 Nov 30; 2022: 2114451.

10. De Venter M, Van Den Eede F. Jeugdtrauma als voorbeschikkende factor voor fibromyalgie en het chronischevermoeidheidssyndroom: een literatuuroverzicht. Tijdschrift voor geneeskunde/Nederlandstalige medische fakulteiten in België-Leuven, 1966-2020. 2013;69(19):912–21.

11. Womersley JS, Nothling J, Toikumo S, Malan-Müller S, van den Heuvel LL, McGregor NW, et al. Childhood trauma, the stress response and metabolic syndrome: A focus on DNA methylation. Eur J Neurosci. 2022 May;55(9-10):2253–96.

12. Bacon AM, White L. The association between adverse childhood experiences, self-silencing behaviours and symptoms in women with fibromyalgia. Psychol Health Med. 2023 Jul-Dec;28(8):2073–83.

13. Maes F, Vanaerschot G, Goossens E, Van Houdenhove B. Fibromyalgia, perfectionism, and interpersonal style. Further evidence for a person-centered approach. Journal of Pain Research and Management. 2025 Jan 1;1(1):11–8.

14. West ML, Keller AE. Parentification of the child: a case study of Bowlby's compulsive care-giving attachment pattern. Am J Psychother. 1991 Jul;45(3):425–31.

15. Rana R, Das A. Parentification: A review paper. The International Journal of Indian Psychology. 2021;9(1):44–50.

16. Minuchin S. Families of the slums: An exploration of their structure and treatment. New York: Basic Books; 1967.

17. Kelley ML, French A, Bountress K, Keefe HA, Schroeder V, Steer K, et al. Parentification and family responsibility in the family of origin of adult children of alcoholics. Addict Behav. 2007 Apr;32(4):675–85.

18. Bowlby J. Separation, volume II: Anxiety and anger. New York, NY: Perseus. 1973.

19. Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. 3. Loss: Sadness and depression. Hogarth Press; 1980.

20. Boszormenyi-Nagy I, Spark GM. Invisible loyalties: Reciprocity in intergenerational familiy therapy. Hagerstown, MD: Harper and Row; 1973.

21. Połomski P, Peplińska A, Lewandowska-Walter A, Borchet J. Exploring Resiliency and Parentification in Polish Adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Oct 30;18(21):11454.

22. Barnett B, Parker G. The parentified child: Early competence or childhood deprivation?. Child Psychology and Psychiatry Review. 1998 Nov;3(4):146–55.

23. Byng-Hall J. Relieving parentified children's burdens in families with insecure attachment patterns. Fam Process. 2002 Fall;41(3):375–88.

24. Sedgwick D. The wounded healer: Countertransference from a Jungian perspective. Routledge; 2016.

25. DiCaccavo A. Working with parentification: implications for clients and counselling psychologists. Psychol Psychother. 2006 Sep;79(Pt 3):469–78.

26. Nuttall AK, Valentino K, Borkowski JG. Maternal history of parentification, maternal warm responsiveness, and children's externalizing behavior. J Fam Psychol. 2012 Oct;26(5):767–75.

27. Nuttall AK, Zhang Q, Valentino K, Borkowski JG. Intergenerational Risk of Parentification and Infantilization to Externalizing Moderated by Child Temperament. J Marriage Fam. 2019 Jun;81(3):648–61.

28. Boszormenyi-Nagy IK. Between give and take: A clinical guide to contextual therapy. Philadelphia: Routledge; 1986.

29. Godsall RE, Jurkovic GJ, Emshoff J, Anderson L, Stanwyck D. Why some kids do well in bad situations: relation of parental alcohol misuse and parentification to children's self-concept. Subst Use Misuse. 2004 Apr;39(5):789–809.

30. Nuttall AK, Zhang Q, Valentino K, Borkowski JG. Intergenerational Risk of Parentification and Infantilization to Externalizing Moderated by Child Temperament. J Marriage Fam. 2019 Jun;81(3):648–61.

31. Davies PT. Conceptual links between Byng-Hall's theory of parentification and the emotional security hypothesis. Fam Process. 2002 Fall;41(3):551–5.

32. Levante A, Martis C, Del Prete CM, Martino P, Pascali F, Primiceri P, et al. Parentification, distress, and relationship with parents as factors shaping the relationship between adult siblings and their brother/sister with disabilities. Front Psychiatry. 2023 Jan 18;13:1079608.

33. Cho A, Lee S. Exploring effects of childhood parentification on adult-depressive symptoms in Korean college students. J Clin Psychol. 2019 Apr;75(4):801–13.

34. Nuttall AK, Ballinger AL, Levendosky AA, Borkowski JG. Maternal parentification history impacts evaluative cognitions about self, parenting, and child. Infant Ment Health J. 2021 May;42(3):315–30.

35. Jurkovic GJ. Lost childhoods: The plight of the parentified child. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1997.

36. Dariotis JK, Chen FR, Park YR, Nowak MK, French KM, Codamon AM. Parentification Vulnerability, Reactivity, Resilience, and Thriving: A Mixed Methods Systematic Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Jun 21;20(13):6197.

37. Peris TS, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM, Emery RE. Marital conflict and support seeking by parents in adolescence: empirical support for the parentification construct. J Fam Psychol. 2008 Aug;22(4):633–42.

38. Hendricks BA, B Vo J, Dionne-Odom JN, Bakitas MA. Parentification Among Young Carers: A Concept Analysis. Child Adolesc Social Work J. 2021 Oct;38(5):519–31.

39. Hooper L. Expanding the discussion regarding parentification and its varied outcomes: Implications for mental health research and practice. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 2007 Oct 1;29(4):322–37.

40. Hooper LM, Marotta SA, Lanthier RP. Predictors of growth and distress following childhood parentification: A retrospective exploratory study. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2008 Oct;17(5):693–705.

41. Johnston JR. Role diffusion and role reversal: Structural variations in divorced families and children's functioning. Family Relations. 1990 Oct 1:405–13.

42. Schier K, Egle U, Nickel R, Kappis B, Herke M, Hardt J. Emotional childhood parentification and mental disorders in adulthood. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, medizinische Psychologie. 2011 May 30;61(8):364–71.

43. McMahon TJ, Luthar SS. Defining characteristics and potential consequences of caretaking burden among children living in urban poverty. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2007 Apr;77(2):267–81.

44. Khafi TY, Yates TM, Luthar SS. Ethnic differences in the developmental significance of parentification. Fam Process. 2014 Jun;53(2):267–87.

45. Serbin L, Karp J. Intergenerational studies of parenting and the transfer of risk from parent to child. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003 Aug;12(4):138–42.

46. Belsky J, Conger R, Capaldi DM. The intergenerational transmission of parenting: introduction to the special section. Dev Psychol. 2009 Sep;45(5):1201–4.

47. Hooper LM. Parentification inventory. Available from LM Hooper, Department of Educational Studies in Psychology, Research Methodology, and Counseling, The University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL. 2009;35487.

48. Hooper LM, Doehler K. Assessing family caregiving: a comparison of three retrospective parentification measures. J Marital Fam Ther. 2012 Oct;38(4):653–66.

49. Jurkovic GJ, Thirkield A, Morrell R. Parentification of adult children of divorce: A multidimensional analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2001 Apr;30(2):245–57.

50. Young JE, Brown G. Young schema questionnaire. Cognitive therapy for personality disorders: A Schema-Focused Approach. 1994;2(1):63–76.

51. Oei TP, Baranoff J. Young Schema Questionnaire: Review of psychometric and measurement issues. Australian Journal of Psychology. 2007 Sep;59(2):78–86.

52. Rijkeboer MM, van den Bergh H, van den Bout J. Stability and discriminative power of the Young Schema-Questionnaire in a Dutch clinical versus non-clinical population. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;36(2):129–44.

53. Pauwels E, Dierckx E, Smits D, Janssen R, Claes L. Validation of the Young Schema Questionnaire-Short Form in a Flemish Community Sample. Psychol Belg. 2018 Apr 23;58(1):34–50.

54. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983 Jun;67(6):361–70.

55. Vallejo MA, Rivera J, Esteve-Vives J, Rodríguez-Muñoz MF; Grupo ICAF. Uso del cuestionario Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) para evaluar la ansiedad y la depresión en pacientes con fibromialgia [Use of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) to evaluate anxiety and depression in fibromyalgia patients]. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2012 Apr-Jun;5(2):107–14. Spanish.

56. el-Rufaie OE, Absood G. Validity study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale among a group of Saudi patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1987 Nov;151:687–8.

57. Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers PP, Kempen GI, Speckens AE, Van Hemert AM. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med. 1997 Mar;27(2):363–70.

58. Nuttall AK, Valentino K, Mark Cummings E, Davies PT. Contextualizing Children's Caregiving Responses to Interparental Conflict: Advancing Assessment of Parentification. J Fam Psychol. 2021 Apr;35(3):276–87.