Introduction

Functional proteomics of seminal plasma has been reviewed by Samanta and co-workers, highlighting greater biologic relevancy and diverse functions of this seminal component to reproductive biology than previously thought [1]. Although not requested for successful fertilization, important biological functions are associated with seminal plasma and the authors suggested that selected proteins may serve as diagnostic biomarkers for various conditions. In most mammalian species, seminal plasma is involved in a variety of processes during sperm maturation, capacitation, acrosome reaction, and sperm-egg interactions [2-5]. Specific seminal plasma proteins have been associated with antioxidant protection of spermatozoa, heparin binding, and fibronectin binding [6-9]. More recent observations indicate that seminal plasma also play an important role in immune function of the female reproductive tract after breeding as well as the fetal development [10-19].

The total protein fraction of equine seminal plasma is approximately 10 mg/ml, and the majority of the proteins range in molecular weight from 12 kDa-30 kDa [3]. One of these proteins, cysteine-rich secretory protein 3 (CRISP3) is a major seminal plasma protein in horses that constitutes 0.3-1.3 mg/ml, and polymorphism within the CRISP3 gene has been positively correlated with fertility [20-22]. We have characterized the expression of CRISP3 in the equine ampulla of the vas deference and to a lesser degree in the seminal vesicles and implied this protein in the regulation of breeding-induced endometritis, where it interacts with polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN)-binding of spermatozoa [16,19]. Another seminal plasma protein that has been associated with breeding-induced endometritis is equine lactoferrin [23]. This 80kDa protein may be involved in sperm-oocyte binding and has also been shown to have iron binding properties suggesting a role for the protein in regulating free iron available for lipid peroxidation as well as in the innate uterine immune system of horses [24-26]. Multiple lactoferrin receptors have been identified in a variety of tissues and cells, suggesting widespread functions of this protein [27]. In addition to sequestering iron, lactoferrin may also interact with leukocyte function through its apparent control of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) [28].

Among other seminal plasma proteins, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) is secreted by both Leydig cells and Sertoli cells, and its receptors have been found on these cells as well as developing spermatozoa, suggesting a role in spermatogenesis [29-32]. Seminal IGF-1 was found in lower concentrations in infertile men with oligospermia, and seminal plasma derived IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 2 (IGFBP-2), and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-5 (IGFB-5) have also been associated with sperm function and fertility rates in mares [33]. A positive relationship was observed between levels of IGF-1 and sperm motility and morphology, and the authors concluded that stallions with high IGF-1 levels had improved overall pregnancy rates [33]. Others have examined enzymes and additional components in equine seminal plasma and found aspartate transferase (AST), glutamyl transferase (GGT), acid phosphatase (ACP), AIP, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), Fe and Zn were associated with semen volume and sperm concentrations, with LDH activity being most highly correlated with semen quality [34]. The authors suggested that a positive correlation between GGT and sperm motility indicated a protection against free radicals. In addition, seminal plasma DNase has been implemented as a sperm protective factor against NETs of spermatozoa [35].

Role of Seminal Plasma in Inflammation and the Innate Immune System in the Equine Female Reproductive Tract

We have focused our investigations on the role of seminal plasma proteins in the interaction between uterine inflammatory cells and spermatozoa in horses. In species with semen deposited into the uterus during ejaculation, such as the horse, most spermatozoa are eliminated from the uterus shortly after breeding, while a small portion of sperm is transported to the oviducts. Sperm transport is enabled by motility of the spermatozoa and uterine contractions. While sperm motility may not be necessary for sperm transport in the cow, pig, and rabbit [36], observations suggest that both sperm motility and myometrial contractility may be important for uterine and oviductal transport of sperm to the ampulla [37-40]. Excess sperm needs to be eliminated from the uterus in a timely fashion to provide a compatible endometrial environment when an embryo descends into the uterine lumen from the oviduct at approximately 6 days after fertilization [41]. This is accomplished through uterine contractions and sperm-induced inflammation, characterized by a balanced pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokine expression leading to a rapid influx of PMNs into the uterine lumen [42]. The mechanism involves increased expression of interleukin-8 (IL-8) as well as the activation of the complement cascade [43-46]. Complement factor C3b coats the spermatozoa and contributes to PMN-binding and phagocytosis [47]. The breeding-induced inflammation results in prostaglandin release [48], which causes additional myometrial contractions 2-6 hours after the initial wave of contractions [39]. The contractions physically clear the uterus from excess spermatozoa, contaminating bacteria, and residual inflammatory fluid/products within 24-36 hours after breeding, with recent unpublished observations suggesting that this process may be completed at a much earlier time point, already within 6 hours in some mares. Impaired uterine contractility following breeding has been associated with infertility due to persistent inflammation that is incompatible with the survival of an embryo [49].

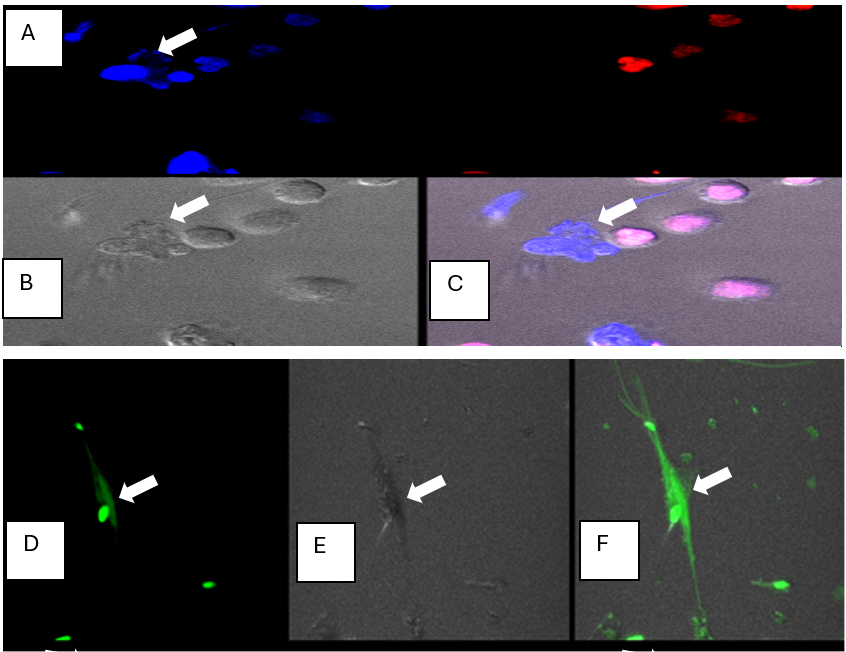

There is accumulating evidence that seminal plasma play an important role in breeding-induced endometritis, specifically in the protection of viable spermatozoa for safe transport in the presence of an inflammatory uterine environment, while allowing dead spermatozoa and bacteria to be eliminated through PMN phagocytosis [13,16,50]. In addition, Alghamdi and Foster demonstrated that PMNs extrude DNA and histone along with their cellular contents to form NETs, similar to what has been described for bacteria, and there also appears to be an additional receptor ligand binding mechanisms between PMNs and spermatozoa that has not been identified [35,51]. We have confirmed these findings (Figure 1), but while Alghamdi and Foster [35] suggested that NETs were triggered by live spermatozoa, we were unable to confirm this observation. Our findings corroborate the works of Fuchs and co-workers who suggested that when fragmentation of DNA is not activated during cell death, it allows the chromatin within the neutrophil to unfold and be extruded into the extracellular space [52]. This is an effective mechanism of extracellular destruction of bacteria and other particles such as fungi and parasites. These authors demonstrated that NET formation was triggered by reactive oxygen species (ROS), either from the PMNs, downstream of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, or in response to exposure to high concentrations of extracellular ROS. Since dead and damaged spermatozoa are releasing ROS, this mechanism appears to support our observation that dead spermatozoa triggered the formation of NETs. The formation of NETs is only partially responsible for sperm-PMN binding, since a greater suppression of PMN/sperm binding occurred when seminal plasma was added to the in vitro assays, compared to when DNase was added [35]. This is also supported by the finding that a seminal plasma derived protein complex of lactoferrin and superoxide dismutase (SOD-3) (LF/SOD3) specifically interacts with dead spermatozoa and promotes binding to PMNs [26].

Figure 1: A-F. Fluorescent confocal microscopy images (63X) of PMN- NET formation in the presence of dead spermatozoa. PMNs and dead spermatozoa were exposed to the dicycloorange DNA stain (red color) of intact DNA in live cells, and Sytox Blue stain (blue color) of dead cells, or dicycloviolet DNA stain (green color) of dead cells. The sytox blue and dicycloviolet also stained the extruded DNA from the PMNs, which entrapped dead spermatozoa (indicated by white arrow). A) dead cells: both sperm and PMNs took up sytox-blue DNA stain, (white arrow denotes NET formed by PMN in contact with dead sperm), and live PMNs which are labeled with dicycloorange DNA stain (red) indicating they are viable with intact DNA; B) image in DIC; C) merged image with both fluorescent channels and DIC; D) PMN-NET visualized by dicylcoviolet DNA stain, showing DNA extrusion from the ruptured PMN. E) Image in DIC F) Merged image in fluorescent channel and DIC. (Adopted from Doty AL: The role of seminal plasma proteins in the interaction between polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) and spermatozoa in the horse. PhD Dissertation, University of Florida, 2012).

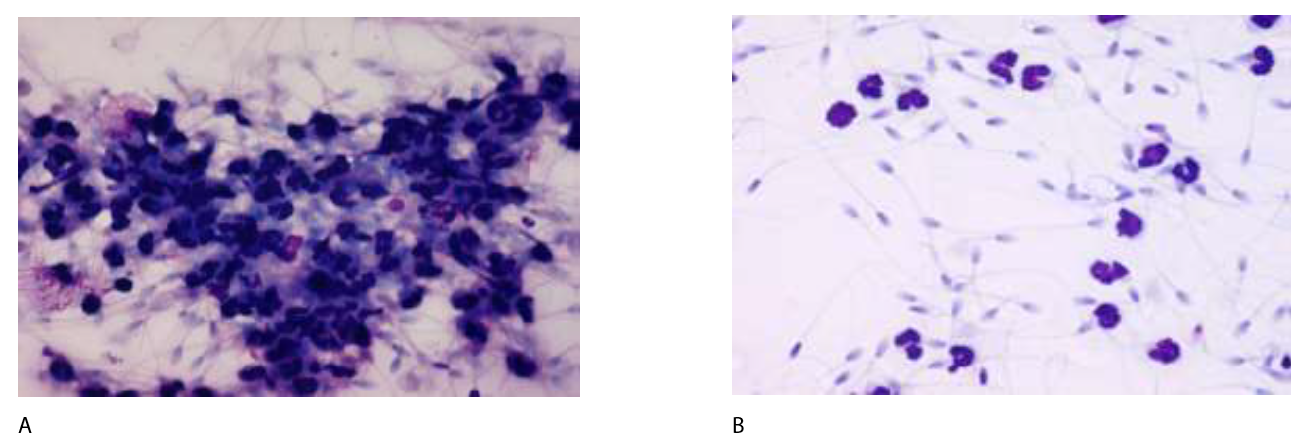

A greater portion of morphologically normal spermatozoa are found in the oviduct, compared to the ejaculate as a whole [53]. While this may be explained by the necessity of motility and membrane integrity during sperm transport through the uterus, it suggests that the utero-tubal junction may serve as a barrier for dead and damaged sperm. In addition, spermatozoa need to be able to survive a hostile inflammatory environment, caused by a rapid influx of PMNs in response to breeding-induced inflammation [54]. The importance of this is illustrated in Figure 2A, showing that spermatozoa form large immobile clusters in the presence of PMNs in vitro. This cluster formation does not occur when the spermatozoa is extended in seminal plasma (Figure 2B). In subsequent experiments, breeding-induced uterine inflammation was induced by insemination with dead sperm, followed by insemination with live spermatozoa 12 hours later, with one group of mares inseminated in the absence of seminal plasma and the other group in the presence of seminal plasma in the insemination dose [12]. Only 5% of the mares became pregnant when inseminated into an inflamed environment in the absence of seminal plasma, while a normal pregnancy rate of 77% was achieved in the presence of seminal plasma. These results were somewhat contradicted by a study showing equal fertility from two individual stallions when their commercially prepared cryopreserved semen was inseminated in the same mare 6-10 hours apart respectively [55]. The difference between the reports is likely explained by the reduction, rather than absence of seminal plasma proteins in cryopreserved semen used in the study by Metcalf, further supporting a selective seminal plasma protection of viable spermatozoa. Seminal plasma derived CRISP-3 was later identified as a protein responsible for protecting spermatozoa from PMN-binding and phagocytosis, and this protective effect was subsequently shown to be selective for live spermatozoa and has no effect on dead sperm or bacteria [16,50]. This suggests a more important biological role of seminal plasma than previously recognized (Table 1).

Figure 2: Photomicrographs of equine spermatozoa mixed with PMNs in the absence (A) and presence (B) of seminal plasma. Spermatozoa formed clusters with reduced motility when seminal plasma was removed from semen (A), while very little binding between PMNs and spermatozoa was observed in the presence of seminal plasma (B), allowing the spermatozoa to maintain motility.

|

Seminal Plasma Protein |

Biological Function |

Reference |

|

CRISP3 |

Selectively prevents binding and phagocytosis of live spermatozoa to PMNs |

[16,50] |

|

LF/SOD-3 |

Selectively promotes binding and phagocytosis of dead spermatozoa to PMNs |

[26] |

|

DNase |

Modulation of NETs |

[35] |

Role of Seminal Plasma in Maternal Immune Tolerance

The deposition of semen into the uterus activates numerous aspects of maternal immunity, including both the innate and adaptive immune system. The compilation of seminal plasma includes various cytokines (transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), IL-8), hormones (PG), in addition to paternal antigens. The exposure of seminal plasma to the maternal immune system is believed to activate the adaptive immune response to develop tolerance to the semi-allogeneic fetoplacental unit [15,56-57]. The impact of seminal plasma on the immune response to breeding includes activation of cytokines and chemokines from the epithelial cells, a recruitment of immune cells into the uterine lumen, and eventual activation of dendritic cells by paternal antigens [42,54,60,61]. Seminal plasma has also been found to increase the expression of various embryokines (leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), interleukin 6 (IL6), colony-stimulating factor 2 (CSF2), tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)) as well as transcripts relating to embryo health and metabolism (IGF-b) [58,59]. In the mouse, seminal plasma induces chemotactic factors for immune cells such as neutrophils, macrophages and dendritic cell, and mating of seminal vesicle-excised males to normal females decreased placental volume, litter size, and had a negative impact on the health of resulting offspring [17]. Others have suggested that seminal vesicle-derived CD38 is imperative in inducing the tolerogenic dendritic cells and CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs. This population of T-cells is believed to be essential for pregnancy maintenance, and depletion of these cells leads to implantation failure, impaired uterine vascular development, and fetal loss in late term gestation [62]. While this has not been extensively investigated in horses, we recently observed that seminal plasma regulated endometrial gene transcription that may have an impact on the environment for the embryo [63]. This can potentially alter embryo development through epigenetic effects and subsequently impacting the phenotype of the offspring. Recent work suggests that equine intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI)-produced embryos were associated with postpartum placentas that had increased chorionic villi hyperplasia, edema, allantoic cysts, and necrosis [64]. Umbilical length of these ICSI-produced fetuses was also shorter in comparison to in vivo produced embryos. Additional work on in vitro produced embryos revealed that equine male offspring produced from embryo transfer and ICSI had higher weight gain during the first two years of age, compared to offspring produced from conventional AI at the same farm [65]. While advanced growth may be considered an advantage for early development in young athletes, it carries an enhanced risk of developmental diseases, such as osteochondrosis dissecans. These findings were preliminary and additional factors associated with Assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) were not evaluated. Nevertheless, data from other species suggest that a potential impact of seminal plasma on fetal development needs to be studied further.

In other species, seminal plasma has been shown to enhance the endometrial and oviductal production of various embryotrophic factors, including CSF1, CSF2, CSF3, IL-6, LIF, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and TRAIL in both mice and pigs [58,66]. When females are mated with seminal vesicle-excised males, a reduced rate of zygote cleavage was noted [17], while infusion of seminal plasma at the time of insemination in these animals reinstated the appropriate inflammatory response, enhanced embryo development, and increased the number of offspring [67]. Furthermore, seminal plasma exposure of the female reproductive tract prior to in vitro fertilization (IVF) and ICSI, improved the success of embryo transfer in women [68,69]. However, IVF in humans does not routinely include seminal plasma and the procedure has been shown to alter placental development [70], neonatal outcomes [71], and offspring health [72]. Seminal vesicle ablation in mice altered growth trajectories in resulting offspring, with elevated adipose tissue, hypertension, and reduced glucose tolerance observed, and this was primarily found in males [17]. The alteration in offspring phenotype is hypothesized to be linked to the reduced embryokine production in the female reproductive tract following insemination with seminal plasma-voided ejaculates. Further investigations are warranted to better understand the role of seminal plasma in fertility, fetal development and the health of offspring when different forms of ART are used in horses and other species. Once these functions are characterized, specific proteins that are associated with immune tolerance and development of the fetus should be identified and possibly added to media when ART is implemented.

Conclusion

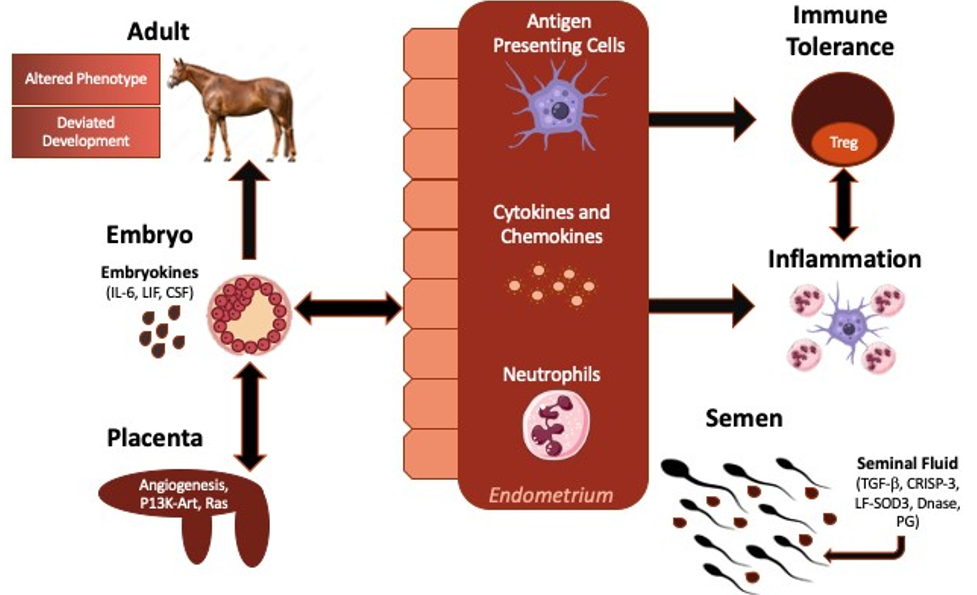

There is accumulating evidence that seminal plasma proteins have distinct biological functions associated with breeding in horses and other species (Figure 3). While the proteins may not be necessary for the establishment of pregnancy, they appear to facilitate the selection of viable sperm in the uterus, as well as ensuring a suitable uterine environment for optimal development of the fetus. The importance of the uterine environment extends beyond gestation and can potentially affect the health of offspring later in life. The role of seminal plasma exposure at the time of breeding should be investigated further regarding its effect on quality aspects of pregnancy and offspring.

Figure 3: Schematic representation of the proposed impact of seminal plasma on the maternal immune response to breeding and pregnancy. Seminal plasma is believed to impact the maternal immune response to breeding, embryo growth and development, in addition to immunotolerance of the developing fetus, all of which are believed to improve pregnancy outcomes and optimize the growth and development of offspring. Proteins, cytokines, and paternal antigen within seminal plasma modulates the immune response to breeding, leading to the production of various cytokines which assist with the innate immune response to breeding, in addition to the cell-mediate immune response to pregnancy. Stimulated antigen presenting cells travel through the draining lymphatics of the uterus to increase the proliferation of immunotolerant lymphocyte populations, specifically Tregs. Seminal plasma is also believed to increase the production of various cytokines, deemed embryokines (IL-6, LIF, CSF), which enhance embryo growth and development. Modified from Bromfield 2016 [73].

References

2. Manjunath P, Thérien I. Role of seminal plasma phospholipid-binding proteins in sperm membrane lipid modification that occurs during capacitation. J Reprod Immunol. 2002 Jan;53(1-2):109-19.

3. Töpfer-Petersen E, Ekhlasi-Hundrieser M, Kirchhoff C, Leeb T, Sieme H. The role of stallion seminal proteins in fertilisation. Anim Reprod Sci. 2005 Oct;89(1-4):159-70.

4. Primakoff P, Myles DG. Penetration, adhesion, and fusion in mammalian sperm-egg interaction. Science. 2002 Jun 21;296(5576):2183-5.

5. Sullivan R. Epididymosomes: a heterogeneous population of microvesicles with multiple functions in sperm maturation and storage. Asian J Androl. 2015 Sep-Oct;17(5):726-9.

6. Calvete JJ, Reinert M, Sanz L, Töpfer-Petersen E. Effect of glycosylation on the heparin-binding capability of boar and stallion seminal plasma proteins. J Chromatogr A. 1995 Sep 8;711(1):167-73.

7. Greube A, Müller K, Töpfer-Petersen E, Herrmann A, Müller P. Interaction of fibronectin type II proteins with membranes: the stallion seminal plasma protein SP-1/2. Biochemistry. 2004 Jan 20;43(2):464-72.

8. Ekhlasi-Hundrieser M, Schäfer B, Kirchhoff C, Hess O, Bellair S, Müller P, et al. Structural and molecular characterization of equine sperm-binding fibronectin-II module proteins. Mol Reprod Dev. 2005 Jan;70(1):45-57.

9. O WS, Chen H, Chow PH. Male genital tract antioxidant enzymes--their ability to preserve sperm DNA integrity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006 May 16;250(1-2):80-3.

10. Tremellen KP, Seamark RF, Robertson SA. Seminal transforming growth factor beta1 stimulates granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor production and inflammatory cell recruitment in the murine uterus. Biol Reprod. 1998 May;58(5):1217-25.

11. Johansson M, Bromfield JJ, Jasper MJ, Robertson SA. Semen activates the female immune response during early pregnancy in mice. Immunology. 2004 Jun;112(2):290-300.

12. Alghamdi AS, Foster DN, Troedsson MH. Equine seminal plasma reduces sperm binding to polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) and improves the fertility of fresh semen inseminated into inflamed uteri. Reproduction. 2004 May;127(5):593-600.

13. Troedsson MH, Desvousges A, Alghamdi AS, Dahms B, Dow CA, Hayna J, et al. Components in seminal plasma regulating sperm transport and elimination. Anim Reprod Sci. 2005 Oct;89(1-4):171-86.

14. Jasper MJ, Tremellen KP, Robertson SA. Primary unexplained infertility is associated with reduced expression of the T-regulatory cell transcription factor Foxp3 in endometrial tissue. Mol Hum Reprod. 2006 May;12(5):301-8.

15. Robertson SA, Guerin LR, Bromfield JJ, Branson KM, Ahlström AC, Care AS. Seminal fluid drives expansion of the CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cell pool and induces tolerance to paternal alloantigens in mice. Biol Reprod. 2009 May;80(5):1036-45.

16. Doty A, Buhi WC, Benson S, Scoggin KE, Pozor M, Macpherson M, et al. Equine CRISP3 modulates interaction between spermatozoa and polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Biol Reprod. 2011 Jul;85(1):157-64.

17. Bromfield JJ, Schjenken JE, Chin PY, Care AS, Jasper MJ, Robertson SA. Maternal tract factors contribute to paternal seminal fluid impact on metabolic phenotype in offspring. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 Feb 11;111(6):2200-5.

18. Zenclussen AC, Hämmerling GJ. Cellular Regulation of the Uterine Microenvironment That Enables Embryo Implantation. Front Immunol. 2015 Jun 17;6:321.

19. Fedorka CE, Scoggin KE, Squires EL, Ball BA, Troedsson MHT. Expression and localization of cysteine-rich secretory protein-3 (CRISP-3) in the prepubertal and postpubertal male horse. Theriogenology. 2017 Jan 1;87:187-192.

20. Schambony A, Gentzel M, Wolfes H, Raida M, Neumann U, Töpfer-Petersen E. Equine CRISP-3: primary structure and expression in the male genital tract. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998 Sep 8;1387(1-2):206-16.

21. Magdaleno L, Gasset M, Varea J, Schambony AM, Urbanke C, Raida M, et al. Biochemical and conformational characterisation of HSP-3, a stallion seminal plasma protein of the cysteine-rich secretory protein (CRISP) family. FEBS Lett. 1997 Dec 29;420(2-3):179-85.

22. Hamann H, Jude R, Sieme H, Mertens U, Töpfer-Petersen E, Distl O, et al. A polymorphism within the equine CRISP3 gene is associated with stallion fertility in Hanoverian warmblood horses. Anim Genet. 2007 Jun;38(3):259-64

23. Fedorka CE, Woodward EM, Scoggin KE, Esteller-Vico A, Squires EL, Ball BA, Troedsson MHT. The effect of cysteine-rich secretory protein-3 (CRISP-3) and lactoferrin on endometrial cytokine expression after breeding in the horse. J Eq Vet Sci. 2017;48:136-142.

24. Inagaki M, Kikuchi M, Orino K, Ohnami Y, Watanabe K. Purification and quantification of lactoferrin in equine seminal plasma. J Vet Med Sci. 2002 Jan;64(1):75-7.

25. Morte MI, Rodrigues AM, Soares D, Rodrigues AS, Gamboa S, Ramalho-Santos J. The quantification of lipid and protein oxidation in stallion spermatozoa and seminal plasma: seasonal distinctions and correlations with DNA strand breaks, classical seminal parameters and stallion fertility. Anim Reprod Sci. 2008 Jun;106(1-2):36-47.

26. Alghamdi AS, Fedorka CE, Scoggin KE, Esteller-Vico A, Beatty K, Davolli G, et al. Binding of Equine Seminal Lactoferrin/Superoxide Dismutase (SOD-3) Complex Is Biased towards Dead Spermatozoa. Animals (Basel). 2022 Dec 23;13(1):52.

27. Suzuki YA, Lopez V, Lönnerdal B. Mammalian lactoferrin receptors: structure and function. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005 Nov;62(22):2560-75.

28. Okubo K, Kamiya M, Urano Y, Nishi H, Herter JM, Mayadas T, et al. Lactoferrin Suppresses Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Release in Inflammation. EBioMedicine. 2016 Aug;10:204-15.

29. Handelsman DJ, Spaliviero JA, Scott CD, Baxter RC. Identification of insulin-like growth factor-I and its receptors in the rat testis. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1985 Aug;109(4):543-9.

30. Vannelli BG, Barni T, Orlando C, Natali A, Serio M, Balboni GC. Insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) and IGF-I receptor in human testis: an immunohistochemical study. Fertil Steril. 1988 Apr;49(4):666-9.

31. Henricks DM, Kouba AJ, Lackey BR, Boone WR, Gray SL. Identification of insulin-like growth factor I in bovine seminal plasma and its receptor on spermatozoa: influence on sperm motility. Biol Reprod. 1998 Aug;59(2):330-7.

32. Naz RK, Padman P. Identification of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 receptor in human sperm cell. Arch Androl. 1999 Sep-Oct;43(2):153-9.

33. Macpherson ML, Simmen RC, Simmen FA, Hernandez J, Sheerin BR, Varner DD, et al. Blanchard TL. Insulin-like growth factor-I and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2 and -5 in equine seminal plasma: association with sperm characteristics and fertility. Biol Reprod. 2002 Aug;67(2):648-54.

34. Pesch S, Bergmann M, Bostedt H. Determination of some enzymes and macro and micro elements in stallion seminal plasma and their correlations to semen quality. Theriogenology 2006;66(2):307-313.

35. Alghamdi AS, Foster DN. Seminal DNase frees spermatozoa entangled in neutrophil extracellular traps. Biol Reprod. 2005 Dec;73(6):1174-81.

36. Overstreet JW, Tom RA. Experimental studies of rapid sperm transport in rabbits. J Reprod Fertil. 1982 Nov;66(2):601-6.

37. Parker WG, Sullivan JJ, First NL. Sperm transport and distribution in the mare. J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 1975 Oct;(23):63-6.

38. Bader H. An investigation of sperm migration into the oviducts of the mare. J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 1982;32:59-64.

39. Troedsson MH, Liu IK, Crabo BG. Sperm transport and survival in the mare. Theriogenology. 1998 Apr 1;49(5):905-15.

40. Katila T, Sankari S, Mäkelä O. Transport of spermatozoa in the reproductive tracts of mares. J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 2000;(56):571-8.

41. Betteridge KJ, Eaglesome MD, Mitchell D, Flood PF, Beriault R. Development of horse embryos up to twenty two days after ovulation: observations on fresh specimens. J Anat. 1982 Aug;135(Pt 1):191-209.

42. Woodward EM, Christoffersen M, Campos J, Betancourt A, Horohov D, Scoggin KE, et al. Endometrial inflammatory markers of the early immune response in mares susceptible or resistant to persistent breeding-induced endometritis. Reproduction. 2013 Mar 1;145(3):289-96.

43. Watson ED, Stokes CR, Bourne FJ. Cellular and humoral defence mechanisms in mares susceptible and resistant to persistent endometritis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1987 Sep;16(1-2):107-21.

44. Troedsson MH, Liu IK, Thurmond M. Immunoglobulin (IgG and IgA) and complement (C3) concentrations in uterine secretion following an intrauterine challenge of Streptococcus zooepidemicus in mares susceptible to versus resistant to chronic uterine infection. Biol Reprod. 1993 Sep;49(3):502-6.

45. Kotilainen T, Huhtinen M, Katila T. Sperm-induced leukocytosis in the equine uterus. Theriogenology. 1994 Feb 2;41(3):629-36.

46. Troedsson MH, Crabo BG, Ibrahim N, Scott M. Mating-induced endometritis: mechanisms, clinical importance, and consequences. In Proceedings of the... annual convention. 1995;(41):11-12.

47. Dahms BJ, Troedsson MHT. The effect of seminal plasma components on opsonisation and PMN-phagocytosis of equine spermatozoa. Theriogenology 2002;58:457-461.

48. Watson ED, Stokes CR, David JS, Bourne FJ, Ricketts SW. Concentrations of uterine luminal prostaglandins in mares with acute and persistent endometritis. Equine Vet J. 1987 Jan;19(1):31-7.

49. Troedsson MH, Liu IK, Ing M, Pascoe J, Thurmond M. Multiple site electromyography recordings of uterine activity following an intrauterine bacterial challenge in mares susceptible and resistant to chronic uterine infection. J Reprod Fertil. 1993 Nov;99(2):307-13.

50. Doty AL, Miller LMJ, Fedorka CE, Troedsson MHT. The role of equine seminal plasma derived cysteine rich secretory protein 3 (CRISP3) in the interaction between polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) and populations of viable or dead spermatozoa, and bacteria. Theriogenology. 2024 Apr 15;219:22-31.

51. Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004 Mar 5;303(5663):1532-5.

52. Fuchs TA, Abed U, Goosmann C, Hurwitz R, Schulze I, Wahn V, et al. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol. 2007 Jan 15;176(2):231-241.

53. Thomas PG, Ball BA, Miller PG, Brinsko SP, Southwood L. A subpopulation of morphologically normal, motile spermatozoa attach to equine oviductal epithelial cell monolayers. Biol Reprod. 1994 Aug;51(2):303-9.

54. Troedsson MH. Uterine clearance and resistance to persistent endometritis in the mare. Theriogenology. 1999 Aug;52(3):461-71.

55. Metcalf ES. The effect of postinsemination endometritis on fertility of frozen stallion semen. In Proceedings 2000 Nov 26: 330-1.

56. Robertson SA, Guerin LR, Moldenhauer LM, Hayball JD. Activating T regulatory cells for tolerance in early pregnancy - the contribution of seminal fluid. J Reprod Immunol. 2009 Dec;83(1-2):109-16.

57. Guerin LR, Moldenhauer LM, Prins JR, Bromfield JJ, Hayball JD, Robertson SA. Seminal fluid regulates accumulation of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in the preimplantation mouse uterus through expanding the FOXP3+ cell pool and CCL19-mediated recruitment. Biol Reprod. 2011 Aug;85(2):397-408.

58. Schjenken JE, Glynn DJ, Sharkey DJ, Robertson SA. TLR4 Signaling Is a Major Mediator of the Female Tract Response to Seminal Fluid in Mice. Biol Reprod. 2015 Sep;93(3):68.

59. Shimada M, Yanai Y, Okazaki T, Noma N, Kawashima I, Mori T, et al. Hyaluronan fragments generated by sperm-secreted hyaluronidase stimulate cytokine/chemokine production via the TLR2 and TLR4 pathway in cumulus cells of ovulated COCs, which may enhance fertilization. Development. 2008 Jun;135(11):2001-11.

60. Troedsson MH, Loset K, Alghamdi AM, Dahms B, Crabo BG. Interaction between equine semen and the endometrium: the inflammatory response to semen. Anim Reprod Sci. 2001 Dec 3;68(3-4):273-8.

61. Woodward EM, Troedsson MH. Inflammatory mechanisms of endometritis. Equine Vet J. 2015 Jul;47(4):384-9.

62. Care AS, Bourque SL, Morton JS, Hjartarson EP, Robertson SA, Davidge ST. Reduction in Regulatory T Cells in Early Pregnancy Causes Uterine Artery Dysfunction in Mice. Hypertension. 2018 Jul;72(1):177-187

63. Troedsson MHT, El-Sheikh-Ali H, Scoggin KE, Humphrey EA, Troutt L, Fedorka CE. The impact of seminal plasma on the equine endometrial transcriptome J Eq Vet Sci. 2023;125:181.

64. Lanci A, Perina F, Armani S, Merlo B, Iacono E, Castagnetti C, et al. Could assisted reproductive techniques affect equine fetal membranes and neonatal outcome? Theriogenology. 2024 Feb;215:125-131.

65. Crook RA, Burleson, M, Troedsson, MHT, Fedorka CE. Association between reduced seminal plasma at the time of breeding and offspring growth and development. Proc Rocky Mountain Reprod Sci Symp. 2024:25.

66. O'Leary S, Jasper MJ, Robertson SA, Armstrong DT. Seminal plasma regulates ovarian progesterone production, leukocyte recruitment and follicular cell responses in the pig. Reproduction. 2006 Jul;132(1):147-58.

67. O'Leary S, Jasper MJ, Warnes GM, Armstrong DT, Robertson SA. Seminal plasma regulates endometrial cytokine expression, leukocyte recruitment and embryo development in the pig. Reproduction. 2004 Aug;128(2):237-47.

68. Friedler S, Ben-Ami I, Gidoni Y, Strassburger D, Kasterstein E, Maslansky B, et al. Effect of seminal plasma application to the vaginal vault in in vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection treatment cycles-a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013 Jul;30(7):907-11.

69. Chicea R, Ispasoiu F, Focsa M. Seminal plasma insemination during ovum-pickup--a method to increase pregnancy rate in IVF/ICSI procedure. A pilot randomized trial. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013 Apr;30(4):569-74.

70. Kong F, Fu Y, Shi H, Li R, Zhao Y, Wang Y, et al. Placental Abnormalities and Placenta-Related Complications Following In-Vitro Fertilization: Based on National Hospitalized Data in China. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 Jun 30;13:924070

71. Peng N, Ma S, Li C, Liu H, Zhao H, Li LJ, et al. Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection May Not Improve Clinical Outcomes Despite Its Positive Effect on Embryo Results: A Retrospective Analysis of 1130 Half-ICSI Treatments. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 Jun 15;13:877471.

72. Hart R, Norman RJ. The longer-term health outcomes for children born as a result of IVF treatment. Part II--Mental health and development outcomes. Hum Reprod Update. 2013 May-Jun;19(3):244-50.

73. Bromfield JJ. A role for seminal plasma in modulating pregnancy outcomes in domestic species. Reproduction. 2016 Dec;152(6):R223-R232.