Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PAC) is an aggressive malignancy that is frequently locally invasive or widely metastatic at the time of diagnosis. As such, morbidity and mortality remain extremely high. Despite growing advances in surgical technique and medical management, the incidence and mortality rate are expected to increase over the next two decades. If the global healthcare community hopes to curb this trend, a multimodal approach is necessary. Over the past several years, there has been significant insight into the risks associated with PAC, as well as recommended diagnostic modalities and treatment approach. This review aims to provide an update on current literature available to educate gastrointestinal and medical oncologic physicians.

Keywords

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, Pancreatic cancer, Modifiable risk factors, Diagnostic imaging, Pancreatic cancer treatment

Abbreviations

PAC: Pancreatic ductal Adenocarcinoma; OS: Overall Survival; DFS: Disease Free Survival; CT: Computed Tomography; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; PET: Positron Emission Tomography

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PAC) is an aggressive malignancy associated with significant morbidity and mortality. There is a paucity of effective screening modalities, and so PAC is often diagnosed when it is either locally advanced or widely metastatic. In the United States (US), PAC is the 4th leading cause of death from cancer in men and women, with an estimated 5-year survival of 9% [1,2]. In 2003, an estimated 31,000 people were diagnosed with, and ultimately succumbed to PAC [3]. The incidence continues to rise, and in 2020, an estimated 57,600 Americans (30,400 males, 27,200 females) will be diagnosed with PAC, with approximately 47,050 (81.7%) (24,640 males, 22,410 females) deaths [4]. In a 4 decade SEER database review of pancreatic cancer trends in the US from 1974 to 2014, the incidence rate of PAC increased by a rate of 1.03% per year, and the overall mortality rate increased at a rate of 2.22% per year [5]. In a more recent SEER review of PAC trends between 2000-2014 in the US, the age adjusted incidence rate rose from 9.96/100,000 to 14.70/100,000, and the incidence-based mortality rate rose from 9.96/100,000 to 12.96/100,000 people [6]. Incidence and mortality rates were higher in white patients, and amongst age groups 20-29 years and >80 years [6]. On a global scale, PAC is the 11th most common reported cancer, and has the 3rd highest reported mortality rate of any malignancy with global 5-year survival between 2-10% [4,5,7,8]. By the year 2040, Globocan estimates that the global incidence of PAC will rise to 815,276 newly diagnosed cases, with an estimated 777,423 deaths [7]. While there have been advances in identification of risk factors, diagnostic techniques, and treatment options, this shocking data indicates an unmet need for better preventative guidance with an emphasis on limiting modifiable risk factors, improved modalities for earlier diagnostic detection, and treatment strategies if the medical community hopes to curb current trends.

Risk Factors

There are established risk factors that correlate with an increased risk of PAC. These can be grouped into non-modifiable and modifiable. Non-modifiable risk factors can be further classified by host differences and genetic/inheritable alterations (Tables 1 and 2).

|

Risk Factors |

|

Modifiable |

|

Smoking |

|

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

|

Alcohol (>60 g/day) |

|

Obesity |

|

Dietary Risk Factors (meat, sweetened drinks) |

|

Infection (HBV, HCV, H. Pylori) |

|

Non-Modifiable |

|

Age (65-74 years) |

|

Gender (Male) |

|

Ethnicity (African American) |

|

ABO blood group (non O blood group) |

|

Risk Reduction |

|

Smoking Cessation for ≥15 years |

|

Metformin for the treatment of T2DM |

|

Statin therapy |

|

Citrus Fruits |

|

Folate supplementation |

|

Asthma/Respiratory Allergies |

|

Inherited Risks |

Mutation/Chromosomal Mutation |

|

Familial Pancreatic Cancer |

BRCA2 and PALB2/13q12-13 |

|

Hereditary Pancreatitis |

PRSS1/7q35 |

|

Hereditary Breast/Ovarian Cancer |

BRCA1 and BRCA2/13q12-13 |

|

Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome |

STK11, LKB1/19p13 |

|

Familial Atypical Multiple-Mole Melanoma Syndrome |

P16/9p21 |

|

Ataxia-Telangiectasia |

ATM/11q22-23 |

|

Lynch Syndrome |

MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, PMS1, PMS2 |

|

Li-Fraumeni Syndrome |

p53/17p13.1 |

|

Cystic Fibrosis |

CFTR/7q31 |

Non-modifiable risk factors/germline mutations

Non-modifiable host risk factors include age, gender, ethnicity, and non-O blood group. PAC is more frequently diagnosed in males and the elderly between the ages of 65-74 years, with a median age of diagnosis at 71 years and death at 72 years [9]. It is theorized that a gender specific variation in cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and occupational exposures contributes to this observed difference, although it is also possible that underlying genetic alterations play a role [10]. Race is a well-known risk factor. Based off of SEER review in the US, African-Americans are more likely to be diagnosed with PAC and are frequently diagnosed at a more advanced stage than Caucasians, Asians/Pacific Islanders, Hispanic, and American Indians [9], although a recently published SEER database review indicates that the current rise in incidence and mortality is predominately occurring in Caucasians [6]. While a host of variations in modifiable risk factors including obesity, smoking, and alcohol consumption exist between ethnic groups and may perpetuate this observed difference, population-based studies suggest that these findings do not fully explain this dissimilarity, so it is possible that additional underlying genetic and molecular predispositions exist [11]. In addition, blood types A, AB, and B have been found to be independent risk factors associated with PAC in epidemiologic studies, with odds ratios (OR) of 1.38 [95% confidence interval (95% CI), 1.18–1.62], 1.47 (95% CI, 1.07–2.02), and 1.53 (95% CI, 1.21–1.92), respectively [12,13], with another study showing type A blood conferring the highest risk of the three [14].

There are also various inherited germline mutations and familial cancer syndromes that have been identified as having a positive correlation of developing PAC (Table 2). BRCA2 mutations have the highest known association with inherited familial risk of pancreatic cancer, but many other germline mutations have been discovered that confer a risk of developing PAC, including BRCA1, PALB2, ATM, CDKN2A, APC, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, PRSS1 and STK11 [10, 15, 16) (Table 2).

Modifiable risk factors: Given the rising global incidence of PAC, it is essential to identify modifiable risk factors in at-risk patients. Established modifiable risk factors include smoking, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), alcohol consumption, diet, obesity, and infections (Table 1) [17].

Smoking: Smoking remains the most significantly associated modifiable risk factor in PAC and has been attributed to 20% of diagnosed PACs [10,18,19]. Smokers are estimated to be twice as likely to develop PAC than nonsmokers, and one meta-analysis found the relative risk of developing PAC in current and former smokers to be 1.74 (95% CI 1.61–1.87) and 1.2 (95% CI 1.11–1.29), respectively [18]. In a large European cohort study, those at highest risk of PAC included those with a ≥ 40 pack year smoking history, smoking for ≥ 50 years, and ≥ 30 cigarettes daily [20]. They also found that the odds of developing PAC decreased to that of a never smoker after smoking cessation for ≥ 15 years suggesting a delayed or late carcinogenic effect [20].

Diabetes Mellitus: Diabetes has been linked with developing PAC since the late 1950s [21,22]. It is possible that up to 1% of patients will be diagnosed with PAC following the diagnosis of T2DM [23]. In an Italian based epidemiologic study, the attributable risk of T2DM was 9.7% (95% CI, 5.3-14.1), a significant association in patients diagnosed with PAC [24]. Utilization of insulin may further increase the risk of developing PAC [25] with data showing a greater RR of developing PAC with insulin (OR 5.60, 95% CI 3.75–8.35) compared to a lower risk with oral hypoglycemic agents (OR 0.31, 95% CI 0.14–0.69). While the risk may decline with the duration of T2DM, a significant risk may persist for more than 2 decades after the diagnosis is made (OR 1.30, 95% CI 1.03-1.63) [27]. A recent risk model called the Enriching New-Onset Diabetes for Pancreatic Cancer (ENDPAC) model has been made using retrospective data and found that the change in weight overtime, average range of blood glucose levels, and age at diagnosis of T2DM are associated with a higher likelihood of PAC. The model subcategorizes patients into low risk (<0), intermediate risk (1-2), and high risk (≥ 3). Sensitivity and specificity for a high-risk patient was at least 80%. While this may be a useful risk model to predict the likelihood of developing T2DM, prospective studies are needed to validate this risk model [28].

Diet-resume: Dietary habits may impart a risk of developing PAC. In Northern Italy, lack of adherence to a Mediterranean diet had an attributable risk of 11.9% [24]. Regular intake of foot mutagens found in cooked and well-done red meats, including 2-amino-3,4,8-trimethylimidazo[4,5-f] quinoxaline (DiMeIQx) and benzo(a)pyrene (BaP), have been studied and considered an independent risk for PAC [29,30]. Consumption of ≥ 2-3 sugar-sweetened soft drinks or juices on a weekly basis [31-33] and high alcohol/liquor consumption has also been linked to a higher associated risk of developing PAC [34], with the latter further increased with concomitant smoking of tobacco products [35]. While several studies have found low-to-moderate alcohol intake by itself does not appreciably impart a risk of PAC, it may become a risk with concomitant smoking [34,35].

Body weight: Obesity (defined as a body mass index [BMI] of ≥ 30kg/m2) has a well-established link with various malignancies, most notably esophageal and endometrial carcinoma, though modest risk elevations are also reported with PAC [36,37]. In a 2011 pooled analysis of PAC, patients that were overweight (BMI ≥ 25mg/kg2) or obese in early adulthood had a 54% and 47% higher likelihood of developing PAC, respectively. Young adults that had a steady weight gain with BMI ≥ 10kg/m2 over time compared to a stable weight over time were 40% more likely to develop PAC. In addition, a higher waist to hip ratio had a pooled relative risk of 1.35 (95% CI 1.03-1.78) [38]. Many of these epidemiologic studies primarily consisted of Caucasian patients, so statistical interpretation and extrapolation to other races/ethnicities has not yet been definitively determined [38].

Infection: Infection, particularly gastric colonization with Helicobacter Pylori, has a population attributable risk of 4-25% [39]. This association has been postulated to be related to the augmentation of carcinogenic mutagens related to dietary intake or tobacco product use [10,40]. Alternatively, other studies have not found an associated risk, so additional long term follow up of these patients is warranted [41]. Infection with Hepatitis B virus and Hepatitis C virus have also been correlated with a positive risk, with meta-analysis suggesting a relative risk ranging from 1.2-3.8 and 1.2, respectively [42-44]. These analyses were limited by a small number of available observational studies in the literature, and a large proportion of patients were of Asian ethnicity, which may limit the capacity by which these results can be inferred to the global population.

PAC risk reduction

Clinicians should be mindful of identifying modifiable risk factors in their patients. Encouraging long term smoking cessation, reduction in dietary intake of red meats, sweetened drinks, and alcohol consumption, reduction of risk factors that may precipitate T2DM or steady weight gain, and high risk practices that may lead to Hepatitis B or C infections may be a possible strategy to reduce this trend over time. While still under investigation and not clearly understood, large epidemiologic studies have found other factors that may reduce the risk of developing PAC or otherwise prolong the survival in patients already diagnosed with PAC. There have been several studies reporting an inverse relationship between respiratory allergies such as hay fever and allergies to plants, animals, or pollen and the risk of developing PAC [45,46]. Asthma has been suggested to have a lower risk of PAC, particularly in patients with asthma for ≥ 17 years [47]. Statin (HMG-coreductase inhibitors) therapy may also play a protective role. One meta-analysis indicated that ever-use of statin reduced the risk of developing PAC by 34% (OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.47-0.92), although sex-stratified analysis indicated this finding was only significant in males [48]. Statins are known to have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects [49]. In addition, they may confer anti-neoplastic properties through the inhibition of key proteins directly involved in tumor proliferation and metastasis [50,51]. In a SEER review, use of a statin was associated with improved survival in stage I-II PAC (Hazard ratio (HR) = 0.79, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.67, 0.93) [50]. The oral diabetic medication metformin may also offer a benefit. In obese mouse models, metformin inhibited pancreatic tumor growth [52]. In patients with T2DM and PAC, treatment with metformin improved survival compared to diabetics on other oral hypoglycemic regimens [53]. Alterations in diet, including frequent consumption of citrus fruits and flavonoids [54,55], as well as folate supplementation have also been suggested to have a modest protective role [56]. Further studies are needed to determine whether these factors are preventative or provide a survival benefit in patients at-risk for, or diagnosed with PAC (Table 1).

Tumor Carcinogenesis and Metastatic Potential

PAC carcinogenesis follows a series of stepwise mutations resulting in the formation of pre-neoplastic lesions with eventual transformation into an invasive malignancy [57]. It can be grouped into three broad yet distinct phases: Acquisition of driver mutations, clonal expansion into a multicellular neoplasm, and introduction of the neoplastic cells into local and distant microenvironments [58,59]. On average, there are 63 genetic alterations per PAC, with Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) activation occurring in 90% of cases [60,61]. KRAS activation leads to uncontrolled cellular proliferation resulting in exponential clonal expansion. This often results in additional mutations in progeny cells, including the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor 2A, TP53, and Mothers Against Decapentaplegic Homolog 4 (SMAD4), the latter being a late carcinogenic event and associated with the development of metastatic disease [62].

In general, mutational analysis suggests metastasis is a late event in PAC [63]. Upon acquisition of the initial driver mutation, it may take up to 2 decades for the development of metastatic disease. One study found that it took 11.7 years from the time the initial driver mutation was acquired to the formation of the malignant parental cell. It required an additional 6.8 years thereafter for the index lesion to form [63]. While this is the typical pathogenesis by which stromal invasion and eventual disease metastasis occurs, cancer cells do not always follow a pre-conceived dogma [59,64]. In fact, mouse models have demonstrated that metastatic dissemination can occur early in carcinogenesis, and although most of these cells do not survive, very few cells are actually needed to establish a metastatic foothold [65,66]. Therefore, it is possible that these metastatic cells can become fully malignant prior to the primary tumor site invading into the pancreatic stroma. It is known that some malignancies have the capability to disseminate early in the disease course and may occur years before the primary malignancy is detected. This has been documented in malignant melanomas, as well as cancers involving the breast, prostate, lungs, colon, and kidneys [67]. This has also rarely been reported in PAC. The authors of the present review published a case in which an adenocarcinoma of unknown primary was diagnosed in the esophagus months before the primary pancreatic body lesion manifested radiographically, suggestive of a profound metastatic potential, and further adding to the diagnostic challenge associated with PAC [59]. While PAC frequently follows a predictable time course, the potential ability of PAC to metastasize early carries profound implications on the treatment selection, outcome, and mortality of these patients. Since PAC screening is only recommended for a very specific subset of patients (see section “PAC Screening”), clinicians should have a low index of suspicion when patients present with concerning symptoms to institute a diagnostic workup for PAC, including when the malignancy is of unknown origin.

Diagnosis

PAC accounts for 90% of all pancreatic cancers, with the majority arising in the pancreatic head, and one-third occurring in the pancreatic body or tail [68]. While presenting symptomatology depends on the anatomic location of the primary pancreatic lesion and distant metastatic sites, patients have a range of presenting features including abdominal discomfort, pain, bloating, dyspepsia, nausea, weight loss, and jaundice.

Diagnosis of PAC requires imaging and ultimately tissue sampling. A range of radiographic imaging techniques are available, including computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), Positron Emission Tomography (PET), and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) (Table 3).

|

Imaging Modality |

Advantage |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

Limitations |

|

CT [69-73] |

Cheap Widely available Validated High PPV for determining unresectability (89-100%) |

89% (Overall)

Ductal Dilation 50%

Hypoattenuation 75%

Ductal Interruption 45%

Distal Atrophy 45%

Contour Abnormalities 15%

CBD Dilation 5% |

90% (Overall)

Ductal Dilation 75%

Hypo-attenuation 84%

Ductal Interruption 82%

Distal Atrophy 96%

Contour Anomalies 92%

CBD Dilation 92% |

Contrast Induced Nephrotoxicity Radiation Exposure Iodine allergies possible Low PPV for determining resectability (45-79%) Poor sensitivity for identifying tumors <2cm |

|

MRI [70, 74, 75] |

No radiation exposure or iodinated contrast dye Better characterization of small (<1cm) hepatic lesions Better characterization of smaller lesions <2cm |

89% |

89% |

Expensive Less readily available Contraindicated for certain metal implants and devices |

|

PET [69,76-78] |

Detection of metastatic disease Monitoring for disease recurrence Monitoring response to chemoradiation

|

Pooled Sensitivities:

Diagnosis 91%

N Stage 64%

Liver Metastasis 67% |

Pooled Specificities: Diagnosis 81%

N Stage 81%

Liver Metastasis 96% |

Expensive Not always readily available Significant radiation exposure Iodinated contrast exposure |

|

EUS [69,79] |

Safe, well tolerated No contrast or radiation exposure Ideal for small masses or questionable lesions on other imaging modalities Ideal for local staging |

≥85% (overall)

T1-T2 staging 72%

T3-T4 staging 90%

Local vascular invasion 87%

|

96% (overall)

T1-T2 staging 90%

T3-T4 staging 72%

Local vascular invasion 92% |

Limited by operator comfort with performing EUS and FNA |

Computed tomography

CT is the most validated, widely available, and most inexpensive imaging modality [69]. PAC typically manifests on CT as an ill-defined mass that has poor enhancement compared to adjacent pancreatic parenchyma, and typically appears as a hypodense lesion, although isodense lesions may also be seen [69]. The combined sensitivity and specificity of PAC is 89% and 90% respectively [70], although these are subject to changed based on various CT findings. When a mass <2 cm is present, the sensitivity drops to 67-77%, and additional imaging techniques should be considered [71-73].

Magnetic resonance imaging

On MRI, PACs are commonly hypointense on pre-contrast T1-weighted images and hypointense or isointense on post-contrast T1-weighted images [74]. Sensitivity and specificity approach 89%, and while more expensive and not as widely available as CTs, there may be more benefit for characterization of smaller lesions <2 cm and better delineation of hepatic metastasis with undetermined malignant potential on CT [70,75].

Positron emission tomography

Eighteen-fluorodeoxyglucose ([18]FDG)-PET and PET/CT is not routinely recommended as an initial diagnostic modality. While the pooled sensitivity and specificity of PET/CT is higher than CT alone, PET/CT performs similarly to CT alone and adds no additional initial diagnostic benefit [69,76-78]. However, data suggests that using PET/CT when assessing tumor response to chemoradiation confers a benefit when monitoring for treatment response or progressive disease [77].

Endoscopic ultrasonography

EUS involves an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy examination under conscious sedation with an echoendoscopy. In general, this is a well-tolerated procedure with the added benefit of having the ability to extract image guided tissue sampling via fine needle aspiration (FNA). This is limited by operator expertise, but studies indicate diagnostic accuracy markedly improves over time likely reflective of operator proficiency with repetition [69]. Sensitivity and specificity for identifying PAC via EUS are >85% and 96%, respectively [60,79]. When EUS combined with FNA, pooled specificity was 95.8% (95% CI, 94.6-96.7), with a positive likelihood ratio of 15.2 (95% CI, 8.5-27.3), and negative likelihood ratio of 0.17 (95% CI, 0.13-0.21) [79].

PAC Screening

At the time of diagnosis, approximately 80-90% of patients have either locally advanced lesions or metastatic disease that are not amenable to surgical resection [80,81]. In the 10% of patients that are candidates for operative resection, nearly 70% are found to have pathologic evidence of disease [17,82]. Metastasis to virtually every organ system has been reported, with the most common sites being the liver, lungs, abdominal lymph nodes, peritoneum, thoracic lymph nodes, and adrenal glands [83]. In rare cases, evidence of metastatic disease may be found prior to radiographic evidence of the primary lesion [59]. While there is ample evidence of the benefit of performing screening colonoscopy, mammography, and Papanicolaou smear in the general population, wide-spread screening for PAC is not realistic given the low population-based prevalence, irrespective of rising trends. However, it has been suggested that a screening system may be feasible for individuals identified as being at high risk (>5% life time risk of developing PAC). These situations include family history of PAC and/or inherited germline mutations associated with elevated risks of PAC [84,85]. In patients with hereditary pancreatitis, a consensus conference agreed that screening for PAC should be offered starting at age 40 years [86]. For patients with familial PAC, screening should be offered at age 50 years [85]. Given the younger median age of PAC diagnosis in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome [87], screening should be offered starting at 30 years of age [88].

Staging and Treatment Update

Staging

Non-metastatic PAC is subdivided into resectable, borderline resectable, and locally advanced. The crucial features that need to be radiographically assessed are the contact of the tumor with the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) or portal vein (PV) as venous structures, and the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), common hepatic artery (CHA), and celiac axis (CA) as major surrounding vasculature [89]. Several criteria have been proposed over the past 12 years to aid in defining resectability status, summarized in Table 4. Commonly used criteria include the NCCN guidelines (updated in 2019) [90], MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) guidelines [91,92], the Americas HepatoPancreato-Biliary Association/Society of Surgical Oncology/Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract 2009 consensus recommendations (AHPBA/SSAT/SSO) expert consensus guidelines [93], and the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) criteria [94] (Table 4). While these criteria share commonalities, there remains no uniform or standardized criteria. Furthermore, at a consensus meeting in 2016, biological and functional risk factors were added to resectability criteria. Biological factors include elevated Carbohydrate Antigen (CA) 19.9 levels above 500 units/mL, regional lymph node metastases, and suspicion of distant metastases without the possibility for pathological proof. Functional factors include PS (ECOG>3) and comorbidities [89,90]. These additional recommendations have resulted in fewer patients classified with resectable disease [89,90].

|

Vein/Artery |

Resectable |

Borderline Resectable |

Locally Advanced |

|

SMV/PV |

Abutmenta or no contact |

Abutment, encasement, or occlusiona-d |

Not reconstructablea-d |

|

SMA |

No contact |

Abutmenta-d |

Encasementa-d |

|

CHA |

No contact |

Contacta, abutmentd, encasementb,c,d |

Abutmentd, contacta, or encasementa-d |

|

Celiac Axis |

No contact |

Abutmenta,d or encasementb,c |

Encasementa-d, and not reconstructablec |

Surgery

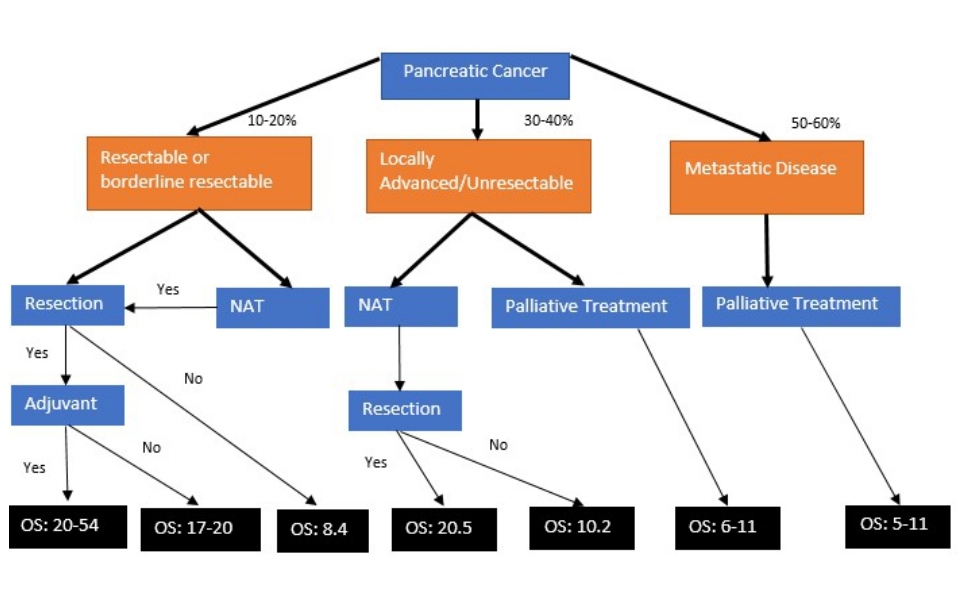

Surgical resection remains the only curative option for PAC. At the time of diagnosis, patients with TNM stages IA-IIB may be considered for resection [95]. Unfortunately, only 10-20% of patients meet this surgically acceptable category at diagnosis (Figure 1). Pancreatico-duodenectomy (Whipple’s procedure), distal pancreatectomy, or total pancreatectomy are the various surgical approaches for PAC. The pathologic goal of surgical resection is to have microscopic margins without evidence of cancer (R0), which improves disease free survival (DFS) and OS compared to tumor resection with microscopic evidence of retained tumor margins (R1) [96]. Prognostic factors used to predict a poor postoperative surgical outcome include tumor size [97,98], vascular invasion [97], number of units of packed red blood cells transfused during surgery [97,98], regional lymph node metastasis [97-99], tumor grade [98], aneuploid karyotype [100], anatomic location [101], the presence of KRAS/TP53 mutations [97,100], and inability to achieve R0 resection [96-99] (Table 5). Contraindications to a surgical intervention include distant metastatic disease, gross vascular tumor invasion into the mesenteric root or celiac axis (stage III-IV) (Table 4), and poor performance status (PS) [95,102].

Figure 1: Treatment outcomes in patients with PAC. OS (overall survival) is reported in months. NAT: Neoadjuvant Therapy.

|

Studies |

Factors |

Prognostic Significance |

Statistical Significance |

|

Cameron et al. [97] Pedrazzoli et al. [98] |

Tumor Size |

>2.0 cm |

<0.05 |

|

Cameron et al. [97] |

Vascular Invasion |

Present |

<0.05 |

|

Cameron et al. [97] Pedrazzoli et al. [98] |

PRBC Transfusion |

≥ 2 units ≥ 4 units |

<0.05 <0.05 |

|

Cameron et al. [97] Pedrazzoli et al. [98] Trede et al. [99] |

Regional LN metastasis |

Present |

<0.05 |

|

Pedrazzoli et al [98] |

Tumor Grade |

Poor |

<0.05 |

|

Allison et al. [100] |

Aneuploid Karyotype |

Present |

<0.005 |

|

Birk et al. [101] |

Anatomic Site |

Uncinate Process |

<0.05 |

|

Demir et al. [96] Cameron et al. [97] Pedrazzoli et al. [98] Trede et al. [99] |

Ro Resection |

Not accomplished |

<0.05 |

|

Cameron et al. [97] Allison et al. [100]

|

Molecular profile |

KRAS/TP53 present |

<0.05 |

Neoadjuvant therapy

The utilization of neoadjuvant therapy (NAT) is being studied in ongoing trials. For locally advanced or borderline resectable disease, NAT may provide a survival benefit. In patients who have surgical exploration and are initially deemed unresectable, initiation of NAT was associated with improved TNM staging, fewer positive lymph nodes, improved survival (24 vs.13 months, P=0.044), and improved resection margins on re-exploration [103]. However, utilization of NAT for resectable PAC remains an emerging notion still being studied. While it is a theoretically reasonable approach to reduce the size of the primary tumor, reduce the high likelihood of preoperative micrometastasis, and increase the likelihood of an R0 resection margins, up to 30% of patients may develop significant AE or disease progression leading to delay or inability to tolerate surgical resection [57,104-106]. Furthermore, it has been difficult to draw sound conclusions due to the inability to achieve target recruitment numbers in randomized trials [107]. In patients with resectable PAC at the time of diagnosis, data is conflicting. In a 2016 meta-analysis of resectable PAC with NAT prior to tumor resection, there was an improvement in median OS (26 months vs. 21 months, P<0.01; hazard ratio, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.68 to 0.78), T stage, lower number of involved regional lymph nodes, and lower positive resection margins. However, the study was limited by the inability to discern the number of patients that received NAT but did not proceed with surgery [108]. In a more recent meta-analysis, Verstaijne and colleagues reported a significant survival benefit when patients with resectable or borderline resectable disease were treated with NAT compared to upfront surgery in an analysis of intention to treat populations. The OS for the total intention to treat population was 18.8 in the NAT group vs 14.8 months in the upfront surgery group, but 17.8% of patients in the NAT group were not able to undergo surgery, primarily due to reported disease progression. For the NAT patients that underwent surgery, the OS compared to the upfront surgery group was 26.1 vs 14.8 months, respectively. The findings also reported a greater R0 resection rate and lower rate of lymph node metastasis [109]. Alternatively, in the first randomized clinical trial assessing chemoradiotherapy (gemcitabine and cisplatin) in the NAT setting, Golcher and colleagues failed to find a statistically significant survival benefit, and the trial was terminated early [110].

Other meta-analyses have reported similar findings. In one analysis assessing per protocol and intention to treat populations, the risk for overall mortality in patients with resectable PAC was lower with NAT compared to upfront surgery in resectable PAC (HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.70–0.92, P < 0.01), with improved R0 resection rates (83.7% in neoadjuvant vs 76.8% in upfront surgery), and less frequently occurring lymph node metastasis (45.0% in neoadjuvant therapy vs. 69.3% in US) [111]. However, in the intention to treat population, these results were not statistically significant and attributed to higher presurgical attrition rate in the neoadjuvant group (36.3% versus 17.3%) [111]. In another recent study, NAT for resectable PAC indicated an increased R0 resection rate (OR=1.89; 95% CI=1.26–2.83) and a reduced positive lymph node rate (OR=0.34; 95% CI=0.31–0.37), but no significant difference in overall survival (OS) time (HR=0.91; 95% CI=0.79–1.05) [111]. Zhan and colleagues assessed NAT vs upfront surgery in resectable, borderline resectable, and locally advanced disease. In patients with resectable disease, 73.0% went on to have surgery, whereas 40.2% of patients with previously borderline resectable or advanced surgery were able to have resection. While survival did not significantly differ for resectable disease, patients with borderline resectable or locally advanced disease may have a survival benefit when NAT is given prior to surgery [104].

In the recently reported results of the randomized, phase III PREOPANC trial, 246 eligible patients with either resectable or borderline resectable disease were randomized into NAT with 3 courses of gemcitabine, the second combined with 15 × 2.4 gray radiotherapy, followed by surgery and 4 courses of adjuvant gemcitabine or to immediate surgery and 6 courses of adjuvant gemcitabine (Table 6). Results from this trial showed that patients randomized into the NAT group had improved R0 resection rates, lower proportion of involvement regional lymph nodes and vascular invasion, better disease free survival, and improved survival if patients that received NAT also had adjuvant chemotherapy (35.2 vs 19.8 months; P=0.029). However, the intention to treat population did not have a significant OS benefit [113]. Further clinical trials including the NEOPA trial [114] assessing the impact of neoadjuvant chemoradiation in PAC of the pancreatic head, NEONAX trial [115] assessing intensified perioperative treatment with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine in resectable PAC), the randomized phase II/III NEPAFOX trial [116] assessing NAT with FOLFIRINOX, phase III NorPACT- 1 randomized trial [117] assessing neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX are ongoing, and phase 2/3 randomized Prep-02/JSAP05 [118] assessing gemcitabine/S1 for resectable/borderline resectable PAC are ongoing.

At this time, the 2019 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines [90] recommend upfront surgery followed by adjuvant therapy for resectable PAC, but recommend the consideration of NAT in patients with imaging findings suspicious of advanced or metastatic disease, significantly elevated CA 19-9, large primary tumors or evidence of regional lymph node involvement, excessive weight loss, and significant pain [90,119]. NAT with either FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel is recommended for patients with borderline resectable disease, with or without subsequent chemoradiotherapy [90,119]. The 2019 American Society of Oncology (ASCO) Clinical Practice Guidelines recommends upfront surgical resection for PAC without radiographic evidence of metastasis, with no tumor invasion of surrounding vasculature, CA 19.9 level suggestive of curable disease, and a PS that supports surgical intervention [120]. NAT is reserved for patients who do not meet these criteria, but no specific treatment recommendations are offered [119,120].

Adjuvant chemotherapy

Even with patients that are candidates for curative surgical resection, OS and DFS remain poor, indicating a significant need to find additional strategies to improve outcomes. There is ample data supporting superior outcomes in OS and DFS associated with adjuvant chemotherapy following surgical resection. In the landmark Charité Onkologie 001 (CONKO 001) phase III randomized controlled trial, adjuvant gemcitabine alone for 6 months after macroscopic resection versus no adjuvant therapy doubled 5-year OS (20.7 vs 10.4 months) and DFS (13.4 vs 6.7 months) (Table 6) [121]. In the final analysis presented at American Society of Oncology in 2016, survival at 3 years and 5 years for adjuvant gemcitabine vs surgery alone was 36.5% and 21.0% vs. 19.5% and 9.0%, respectively [122]. Despite these results, median OS while statistically significant was 22.8 months with gemcitabine vs. 20 months with operative resection alone [122]. Adding to these findings, the phase III randomized multicenter ESPAC 4 trial found further OS and DFS benefit by adding capecitabine to gemcitabine. Results from this study found that median OS for capecitabine + gemcitabine vs. gemcitabine alone was statistically improved at 28.0 vs 25.5 months, respectively, with the caveat that a larger proportion of patients on the combined regimen reported grade 3-4 adverse events (Table 6) [123]. In 2018, the phase III randomized PRODIGE 24/CCTG PA.6 trial compared gemcitabine with modified oxaliplatin, leucovorin (LV), irinotecan, and 5-Flourouracil (5FU) (mFOLFIRINOX) in R0/R1 PAC resection patients with a PS ≤1 for 6 months. Patients that received mFOLFIRINOX were found to have a significantly longer DFS and OS of 21.6 and 54.4 months, respectively, compared to gemcitabine alone with a DFS and OS of 12.8 and 34.8 months, respectively. A larger proportion of grade 3 and 4 AE occurred with mFOLFIRINOX, but it remains the adjuvant therapy standard of care in patients with good PS following surgical resection [124,125]. In the 2019 phase 3 APACT trial, the use of adjuvant nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine was compared to gemcitabine alone for 6 months following surgical resection. OS and DFS in the nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine group compared to gemcitabine alone was 40.5 vs 36.2 months (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.680-0.996; P=0.045), and 16.6 vs. 13.7 months ((HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.694 - 0.965; nominal P=0.0168), respectively [126] (Table 6).

|

Trial |

Type of Treatment |

Regimen |

Sample Size (n) |

OS (months) |

DFS (months) |

|

PREOPANC-1 |

NAT |

Gemcitabine/radiation vs surgery |

246 |

16 vs 14.3 |

11.2 vs 7.9 |

|

PREP-02/JSAP-05 |

NAT |

Gemcitabine/S1 vs Surgery |

364 |

36.7 vs 26.6 |

|

|

CONKO-001 |

Adjuvant |

Gemcitabine vs no therapy |

368 |

20.7 vs 10.4 |

13.4 vs 6.7 |

|

Prodige |

Adjuvant |

mFOLFIRINOX vs Gemcitabine |

487 |

54.4 vs 35 |

21.6 vs 12.8 |

|

ESPAC-4 |

Adjuvant |

Capectiabine/Gemcitabine vs. Gemcitabine |

730 |

28.0 vs 25.5 |

13.9 vs 13.1 |

|

APACT |

Adjuvant |

Nab-Paclitaxel/Gemcitabine vs Gemcitabine |

866 |

40.5 vs 36.2 |

16.6 vs 13.7 |

|

PRODIGE4/ ACCORD11 |

Palliative |

FOLFIRINOX vs gemcitabine |

342 |

11.1 vs 6.8 |

6.4 vs 3.3 |

|

MPACT |

Palliative |

Nab-Paclitaxel/Gemcitabine vs gemcitabineq |

861 |

8.5 vs 6.7 |

5.5 vs 3.7 |

|

NAPOLI-1 |

Palliative |

Liposomal Irinotecan/5FU vs 5FU |

417 |

6.1 vs 4.2 |

3.1 vs 1.5 |

|

CONKO-003 |

Palliative |

Oxaliplatin/5FU vs 5FU |

160 |

5.9 vs 3.3 |

2.9 vs 2 |

|

POLO |

Palliative (BRCA mutation) |

Olaparib maintenance |

154 |

18.9 vs 18.1 |

7.4 vs 3.8 |

Metastatic disease

Treatment for metastatic disease involves chemotherapy with palliative intent and is based strongly off the patient’s PS and symptom control given the high risk for systemic toxicity. With current standard of care systemic chemotherapy, median PFS is approximately 6 months and less than 10% are alive at 5 years (Figure 1) [10,127]. In general, FOLFIRINOX is the preferred first line regimen. In the 2011 PRODIGE4/ ACCORD11 trial comparing between FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine, patients treated with FOLFIRINOX had a significantly longer survival (11.1 months) than Gemcitabine (6.8 months) (HR: 0.57; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.45 to 0.73; P<0.001), improved progression free survival (PFS) of 6.4 vs. 3.3 months, respectively (HR: 0.47; 95% CI, 0.37 to 0.59; P<0.001), and a better objective response rate (ORR) of 31.6% compared to 9.4%, respectively (Table 6). While more patients in the FOLFIRINOX group had significant toxicities reported, fewer reported a degradation in the quality of life (HR: 0.47; 95% CI, 0.30 to 0.70; P<0.001) [127]. In a recent phase 2 trial, the safety and efficacy of mFOLFIRINOX (no 5FU bolus) was assessed. In this group of 69 patients in Japan, median OS was 11.2 months (95%CI 9.0-), with a median PFS of 5.5 months (95% CI 4.1-6.7). The ORR was 37.7% (95% CI 26.3-50.2). There were 47.8% of patients with a grade 3 or higher AE, with 1 treatment related death. The authors concluded mFOLFIRINOX had an improved safety profile with similar median survival [128].

In patients that previously received first-line treatment with FOLFIRINOX and have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group PS of 0-1 with disease progression, the 2019 ASCO clinical practice guidelines recommend second line therapy with gemcitabine plus nanoparticle albumin-bound (nab)-paclitaxel [120]. In the phase 3 MPACT trial assessing the combination regimen, the median OS for nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine vs gemcitabine alone was 8.6 months and 6.7 months, respectively (0.72; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.62 to 0.83; P<0.001) (Table 6). The median PFS was 5.5 months for nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine and 3.3 months for gemcitabine alone (HR: 0.69; 95% CI, 0.58 to 0.82; P<0.001) [129]. In the updated survival analysis, 1, 2, and 3 year survival was superior in the gemcitabine and Nab-paclitaxel (35%, 10%, 4%, respectively) treatment arm compared to gemcitabine alone (22%, 5.0%, and 0%, respectively) [130]. Whether FOLFIRINOX or Nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine should be used as first line therapy remains uncertain. In a recent retrospective cohort study, patients that received FOLFIRINOX first line were younger and had a better PS. However, the median OS (10.7 vs 12.1 mo; P = 0.157), PFS (8.0 vs 8.4 mo; P = 0.134), and ORR (33.7% vs 46.9%; P=0.067) were not significantly different [131]. In a recent propensity score matched analysis comparing FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine/Nab-Paclitaxel, median OS was significantly better in the FOLFIRNOX group (14 vs 9 months respectively, p=0.008), with the authors concluding that gemcitabine/Nab-Paclitaxel following FOLFIRINOX treatment failure is a reasonable approach [132]. In another retrospective study of 83 patients treated with either first line FOLFIRINOX followed by Gemcitabine/Nab-Paclitaxel or vice-versa, there was no significant difference in OS (13.7 vs. 13.8 months, p=0.9), leading to the authors to conclude either sequence leads to a similar outcome in OS [133]. In patients that received mFOLFIRINOX compared to Gemcitabine/Nab-Paclitaxel, patients in the Gemcitabine/Nab-Paclitaxel groups had significantly longer 1 year median OS compared to the mFOLFIRINOX (67% vs 44%, p=0.0006) and better ORR (39% vs 27%, p=0.02), suggesting Gemcitabine/Nab-Paclitaxel had favorable efficacy and survival compared to mFOLFIRINOX [134]. While FOLFIRINOX is the generally accepted first line therapy, to truly compare the efficacy and survival benefit between FOLFIRINOX and Nab-Paclitaxel/Gemcitabine, additional prospective studies are needed.

In patients previously treated with a gemcitabine based chemotherapy who have progressive disease and a PS of 0-1, it is recommended patients be offered nanoliposomal irinotecan (nal-IRI) with either 5FU or oxaliplatin [135]. These recommendations are based on significantly improved median overall survival compared with 5-FU/LV alone (6.1 vs 4.2 months; HR: 0.67, 95% CI 0·49–0·92; p=0.012) in the global phase 3 NAPOLI-1 trial (Table 6). In the final OS survival analysis, estimated one-year overall survival rates were 26% with nal-IRI+5-FU/LV and 16% with 5-FU/LV [136]. As is frequently seen in the real-world clinical setting, utilization of this regimen may be more used in a sicker population with poorer PS and comorbidity profile. In the initial results of a multicenter, retrospective real-world chart review, 26 patients given liposomal irinotecan were older (median age, 68 years), sicker (81% had an ECOG PS ≥ 1), and 65% had 2 or more lines of previous chemotherapy, but had a similar median OS of 4.9 months [137]. In areas that lack availability of 5FU and nan-IRI, fluorouracil plus irinotecan or fluorouracil plus oxaliplatin may be offered [135], recommendations that stem from improved OS (5.9 months, HR: 0.66; 95% CI, 0.48 to 0.91; log-rank P = .010) found in the CONKO-003 trial [138]. In patients with an ECOG PS of 2 or with significant comorbidities, gemcitabine or fluorouracil monotherapy can be considered [135].

At the time of diagnosis, the NCCN recommends that patients with PAC should undergo germline testing using a comprehensive gene panel to assess for hereditary cancers [90]. The 4.6% of patients that are found to have a loss of function mutation in BRCA1/2 may benefit from the oral poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor Olaparib, which has been shown to have activity as a monotherapy [90,139-141]. In a 2015 multicenter phase 2 study of Olaparib in various malignancies with BRCA1/2 mutation, the tumor response rate for the 23 patients included with PAC at ≥ 8 weeks was 35% (95% CI, 16.4 to 57.3) [140]. In the recent phase 3 POLO (Pancreas Cancer Olaparib Ongoing) trial assessing efficacy of Olaparib in patients who previously received a first line platinum base chemotherapy regimen without disease progression, patients in the treatment arm had significantly improved PFS compared to placebo (7.4 months vs. 3.8 months; HR 0.53; 95% CI 0.35-0.82; P=0.004) (Table 6). At 2 years, 22.1% of patients in the Olaparib group did not have progression or death compared to 9.6% in the placebo arm [141]. As a result, the NCCN recommends Olaparib as maintenance therapy in patients with metastatic PAC, a germline BRCA1/2 mutation, no evidence of disease progression in the first 16 weeks of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, and a good PS [90].

Immune check point inhibitor therapy

Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) is an emerging therapeutic option for a broad range of malignancies. This is particularly true for patients with deficiencies in mismatch repair (dMMR) or confirmed microsatellite instability (MSI). In 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved pembrolizumab for dMMR that can lead to high levels of MSI, regardless of disease site [142]. As such, routine testing for dMMR or MSI is recommended [135]. One study found that in PAC, only 0.8% (7/833) of patients had dMMR and high MSI [142]. Of these, 4 were treated with checkpoint inhibitor therapy, and all 4 benefitted from treatment (1 complete response, 2 partial responses, 1 stable disease) [143]. In general, the currently available studies that utilize ICIs in PAC comprise relatively small sample sizes, which make it difficult to draw definitive conclusions on recommended use. A recent review article by Henriksen and colleagues provides a comprehensive report on the available ICI used in PAC [144].

There have been several trials looking at both ICI monotherapy and combination therapy in the adjuvant setting and in patients with either locally advanced or metastatic disease. In a phase II study using monotherapy with the CTLA-4 inhibitor ipilimumab in 27 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, no response was noted, with the exception of a delayed response in one patient with regression of the primary tumor and the metastatic sites. Median OS in this small cohort was 4.5 months [145]. In a randomized phase II trial, 65 patients with metastatic PAC pre-treated with chemotherapy that were given durvalumab monotherapy with or without tremelimumab had a modest improvement in OS of 3.1 vs 3.3 months respectively, and the same PFS of 1.5 months [146].

There are several treatment combination regimens that have been studied in the neoadjuvant and palliative settings. In a phase Ib/II study comparing neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy alone vs in combination with pembrolizumab, the initial results of the first 22 patients have been reported. Of the 14 enrolled in the pembrolizumab treatment arm, 10 (71.4%) underwent surgical resection, and the combination was safely tolerated [147]. In a prospective pilot study assessing durvalumab or durvalumab plus tremelimumab in combination with stereotactic body radiation therapy in chemorefractory, metastatic PAC, 24 patients were enrolled. While 21 (87.5%) had stable disease, none of the patients had an objective response [148]. In the Canadian Cancer Trials PA.7 phase II trial, 11 patients with previously untreated metastatic PAC were treated with Gemcitabine, nab-Paclitaxel, durvalumab, and tremelimumab. In the safety analysis group, 8 (72.7%) patients had a partial response, with a median response duration of 7.4 months, and 6 month survival rate of 80% (95% C.I 40.9%-94.6%). The randomized phase II trial is ongoing and international phase III study is planned [149]. While there have been other reported trials and ongoing studies assessing ICI in various combination setting, low sample size may preclude definitive conclusions.

Conclusion

PAC remains an aggressive malignancy with diagnosis often late in the disease course and poor outcomes, even when curative surgical resection is plausible. Improved understanding in modifiable risk factors over the past decade and educating the medical community of these risks so that appropriate recommendations may be given to patients may provide an outlet by which the long term rising incidence of PAC is curbed. In patients diagnosed with PAC, OS continues to slowly rise with strides in surgical resection, adjuvant chemotherapy, and palliative chemotherapy. Additional research is ongoing for neoadjuvant therapy and additional lines of therapy including checkpoint inhibitors for metastatic disease.

References

2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2019 Jan;69(1):7-34.

3. Jemal A, Tiwari RC, Murray T, Ghafoor A, Samuels A, Ward E, Feuer EJ, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2004. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2004 Jan;54(1):8-29.

4. Key Statistics for Pancreatic Cancer, American Cancer Society. Last revised: January 8, 2020. Available from: URL: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/pancreatic-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Last Accessed: 6/22/2020

5. Saad AM, Turk T, Al-Husseini MJ, Abdel-Rahman O. Trends in pancreatic adenocarcinoma incidence and mortality in the United States in the last four decades; a SEER-based study. BMC Cancer. 2018 Dec;18(1):688.

6. Wu W, He X, Yang L, Wang Q, Bian X, Ye J, et al. Rising trends in pancreatic cancer incidence and mortality in 2000–2014. Clinical Epidemiology. 2018;10:789.

7. International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. Global Cancer Observatory 2018; Available from: URL: http://gco.iarc.fr. Last accessed: 6/22/2020.

8. Ilic M, Ilic I. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2016 Nov 28;22(44):9694.

9. Cancer Stat Facts: Pancreatic Cancer. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, National Cancer Institute. Available From: URL: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/pancreas.html. Last Accessed: 6/22/2020.

10. Rawla P, Sunkara T, Gaduputi V. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer: global trends, etiology and risk factors. World Journal of Oncology. 2019 Feb;10(1):10.

11. Arnold LD, Patel AV, Yan Y, Jacobs EJ, Thun MJ, Calle EE, et al. Are racial disparities in pancreatic cancer explained by smoking and overweight/obesity?. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers. 2009 Sep 1;18(9):2397-405.

12. Wolpin BM, Chan AT, Hartge P, Chanock SJ, Kraft P, Hunter DJ, et al. ABO blood group and the risk of pancreatic cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2009 Mar 18;101(6):424-31.

13. Wolpin BM, Kraft P, Gross M, Helzlsouer K, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Steplowski E, et al. Pancreatic cancer risk and ABO blood group alleles: results from the pancreatic cancer cohort consortium. Cancer Research. 2010 Feb 1;70(3):1015-23.

14. Li X, Xu H, Gao P. ABO blood group and diabetes mellitus influence the risk for pancreatic cancer in a population from China. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research. 2018;24:9392.

15. Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Pancreatic cancer. The Lancet. 2011 Aug 13;378(9791):607-20.

16. Solomon S, Das S, Brand R, Whitcomb DC. Inherited pancreatic cancer syndromes. Cancer Journal (Sudbury, Mass.). 2012 Nov;18(6):485.

17. Midha S, Chawla S, Garg PK. Modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for pancreatic cancer: A review. Cancer Letters. 2016 Oct 10;381(1):269-77.

18. Iodice S, Gandini S, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB. Tobacco and the risk of pancreatic cancer: a review and meta-analysis. Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 2008 Jul 1;393(4):535-45.

19. Alsamarrai A, Das SL, Windsor JA, Petrov MS. Factors that affect risk for pancreatic disease in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2014 Oct 1;12(10):1635-44.

20. Lynch SM, Vrieling A, Lubin JH, Kraft P, Mendelsohn JB, Hartge P, et al. Cigarette smoking and pancreatic cancer: a pooled analysis from the pancreatic cancer cohort consortium. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009 Aug 15;170(4):403-13.

21. Bell ET. Carcinoma of the pancreas: I. A clinical and pathologic study of 609 necropsied cases. II. The relation of carcinoma of the pancreas to diabetes mellitus. The American Journal of Pathology. 1957 Jun;33(3):499.

22. Green RC, Baggenstoss AH, and Sprague RG. Diabetes Mellitus is associated with primary carcinoma of the pancreas. Diabetes. 1958; 7:308-311.

23. Chari ST, Leibson CL, Rabe KG, Ransom J, De Andrade M, Petersen GM. Probability of pancreatic cancer following diabetes: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2005 Aug 1;129(2):504-11.

24. Rosato V, Polesel J, Bosetti C, Serraino D, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Population attributable risk for pancreatic cancer in Northern Italy. Pancreas. 2015 Mar 1;44(2):216-20.

25. Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Ghadirian P, Baghurst PA, Zatonski WA, et al. Past medical history and pancreatic cancer risk: results from a multicenter case-control study. Annals of Epidemiology. 2010 Feb 1;20(2):92-8.

26. Cui Y, Andersen DK. Diabetes and pancreatic cancer. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2012 Oct 1;19(5):F9-26.

27. Bosetti C, Rosato V, Li D, Silverman D, Petersen GM, Bracci PM, et al. Diabetes, antidiabetic medications, and pancreatic cancer risk: an analysis from the International Pancreatic Cancer Case-Control Consortium. Annals of Oncology. 2014 Oct 1;25(10):2065-72.

28. Sharma A, Kandlakunta H, Nagpal SJ, Feng Z, Hoos W, Petersen GM, et al. Model to determine risk of pancreatic cancer in patients with new-onset diabetes. Gastroenterology. 2018 Sep 1;155(3):730-9.

29. Zheng W, Lee SA. Well-done meat intake, heterocyclic amine exposure, and cancer risk. Nutrition and Cancer. 2009 Jul 17;61(4):437-46.

30. Li D, Day RS, Bondy ML, Sinha R, Nguyen NT, Evans DB, et al. Dietary mutagen exposure and risk of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers. 2007 Apr 1;16(4):655-61.

31. Schernhammer ES, Hu FB, Giovannucci E, Michaud DS, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, et al. Sugar-sweetened soft drink consumption and risk of pancreatic cancer in two prospective cohorts. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers. 2005 Sep 1;14(9):2098-105.

32. Larsson SC, Bergkvist L, Wolk A. Consumption of sugar and sugar-sweetened foods and the risk of pancreatic cancer in a prospective study. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006 Nov 1;84(5):1171-6.

33. Mueller NT, Odegaard A, Anderson K, Yuan JM, Gross M, Koh WP, et al. Soft drink and juice consumption and risk of pancreatic cancer: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers. 2010 Feb 1;19(2):447-55.

34. Wang YT, Gou YW, Jin WW, Xiao M, Fang HY. Association between alcohol intake and the risk of pancreatic cancer: a dose–response meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Cancer. 2016 Dec 1;16(1):212.

35. Rahman F, Cotterchio M, Cleary SP, Gallinger S. Association between alcohol consumption and pancreatic cancer risk: A case-control study. PLoS One. 2015 Apr 9;10(4):e0124489.

36. Avgerinos KI, Spyrou N, Mantzoros CS, Dalamaga M. Obesity and cancer risk: Emerging biological mechanisms and perspectives. Metabolism. 2019 Mar 1;92:121-35.

37. Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Bianchini F, Straif K. Body fatness and cancer—viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016 Aug 25;375(8):794-8.

38. Genkinger JM, Spiegelman D, Anderson KE, Bernstein L, Van Den Brandt PA, Calle EE, et al. A pooled analysis of 14 cohort studies of anthropometric factors and pancreatic cancer risk. International Journal of Cancer. 2011 Oct 1;129(7):1708-17.

39. Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB. Risk factors for pancreatic cancer: a summary review of meta-analytical studies. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2015 Feb 1;44(1):186-98.

40. Risch HA. Etiology of pancreatic cancer, with a hypothesis concerning the role of N-nitroso compounds and excess gastric acidity. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2003 Jul 2;95(13):948-60.

41. Chen XZ, Schöttker B, Castro FA, Chen H, Zhang Y, Holleczek B, et al. Association of helicobacter pylori infection and chronic atrophic gastritis with risk of colonic, pancreatic and gastric cancer: A ten-year follow-up of the ESTHER cohort study. Oncotarget. 2016 Mar 29;7(13):17182.

42. Wang Y, Yang S, Song F, Cao S, Yin X, Xie J, et al. Hepatitis B virus status and the risk of pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2013 Jul 1;22(4):328-34.

43. Luo G, Hao NB, Hu CJ, Yong X, Lü MH, Cheng BJ, et al. HBV infection increases the risk of pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer Causes & Control. 2013 Mar 1;24(3):529-37.

44. Fiorino S, Chili E, Bacchi-Reggiani L, Masetti M, Deleonardi G, Grondona AG, et al. Association between hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus infection and risk of pancreatic adenocarcinoma development: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pancreatology. 2013 Mar 1;13(2):147-60.

45. Anderson LN, Cotterchio M, Gallinger S. Lifestyle, dietary, and medical history factors associated with pancreatic cancer risk in Ontario, Canada. Cancer Causes & Control. 2009 Aug 1;20(6):825-34.

46. Eppel A, Cotterchio M, Gallinger S. Allergies are associated with reduced pancreas cancer risk: A population‐based case–control study in Ontario, Canada. International Journal of Cancer. 2007 Nov 15;121(10):2241-5.

47. Gomez-Rubio P, Zock JP, Rava M, Marquez M, Sharp L, Hidalgo M, et al. Reduced risk of pancreatic cancer associated with asthma and nasal allergies. Gut. 2017 Feb 1;66(2):314-22.

48. Walker EJ, Ko AH, Holly EA, Bracci PM. Statin use and risk of pancreatic cancer: results from a large, clinic-based case-control study. Cancer. 2015 Apr 15;121(8):1287-94.

49. Blanco-Colio LM, Tuñón J, Martín-Ventura JL, Egido J. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of statins. Kidney International. 2003 Jan 1;63(1):12-23.

50. Jeon CY, Pandol SJ, Wu B, Cook-Wiens G, Gottlieb RA, Merz NB, et al. The association of statin use after cancer diagnosis with survival in pancreatic cancer patients: a SEER-medicare analysis. PloS One. 2015 Apr 1;10(4):e0121783.

51. Gronich N, Rennert G. Beyond aspirin—cancer prevention with statins, metformin and bisphosphonates. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2013 Nov;10(11):625.

52. Cifarelli V, Lashinger LM, Devlin KL, Dunlap SM, Huang J, Kaaks R, et al. Metformin and rapamycin reduce pancreatic cancer growth in obese prediabetic mice by distinct microRNA-regulated mechanisms. Diabetes. 2015 May 1;64(5):1632-42.

53. Zhou PT, Li B, Liu FR, Zhang MC, Wang Q, Li YY, et al. Metformin is associated with survival benefit in pancreatic cancer patients with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017 Apr 11;8(15):25242.

54. Bae JM, Lee EJ, Guyatt G. Citrus fruit intake and pancreatic cancer risk: a quantitative systematic review. Pancreas. 2009 Mar 1;38(2):168-74.

55. Nöthlings UT, Murphy SP, Wilkens LR, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN. Flavonols and pancreatic cancer risk: the multiethnic cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007 Oct 15;166(8):924-31.

56. Gong Z, Holly EA, Bracci PM. Intake of folate, vitamins B 6, B 12 and methionine and risk of pancreatic cancer in a large population-based case–control study. Cancer Causes & Control. 2009 Oct 1;20(8):1317-25.

57. McGuigan A, Kelly P, Turkington RC, Jones C, Coleman HG, McCain RS. Pancreatic cancer: A review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2018 Nov 21;24(43):4846.

58. Makohon-Moore A, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. Pancreatic cancer biology and genetics from an evolutionary perspective. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2016 Sep;16(9):553.

59. Burns EA, Kasparian S, Khan U, Abdelrahim M. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma with early esophageal metastasis: A case report and review of literature. World Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020 Feb 24;11(2):83.

60. Jones S, Zhang X, Parsons DW, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science. 2008 Sep 26;321(5897):1801-6.

61. Mohammed S, George Van Buren II, Fisher WE. Pancreatic cancer: advances in treatment. World Journal of Gastroenterology: WJG. 2014 Jul 28;20(28):9354.

62. Ahmed S, Schwartz C, Dewan MZ, Xu R. The Promising Role of TGF-β/SMAD4 in Pancreatic Cancer: The future targeted therapy. Journal of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis. 2019 May 29;3(2):1-7.

63. Yachida S, Jones S, Bozic I, Antal T, Leary R, Fu B, et al. Distant metastasis occurs late during the genetic evolution of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2010 Oct;467(7319):1114-7.

64. Malkoski SP, Wang XJ. Two sides of the story? Smad4 loss in pancreatic cancer versus head-and-neck cancer. FEBS Letters. 2012 Jul 4;586(14):1984-92.

65. Rhim AD, Mirek ET, Aiello NM, Maitra A, Bailey JM, McAllister F, et al. EMT and dissemination precede pancreatic tumor formation. Cell. 2012 Jan 20;148(1-2):349-61.

66. Fidler IJ. Metastasis: quantitative analysis of distribution and fate of tumor emboli labeled with 125I-5-iodo-2'-deoxyuridine. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1970 Oct 1;45(4):773-82.

67. Friberg S, Nystrom A. Cancer metastases: early dissemination and late recurrences. Cancer Growth and Metastasis. 2015 Jan;8:CGM-S31244.

68. Barreto SG, Shukla PJ, Shrikhande SV. Tumors of the pancreatic body and tail. World Journal of Oncology. 2010 Apr;1(2):52.

69. Zhang L, Sanagapalli S, Stoita A. Challenges in diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2018 May 21;24(19):2047.

70. Treadwell JR, Zafar HM, Mitchell MD, Tipton K, Teitelbaum U, Jue J. Imaging tests for the diagnosis and staging of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a meta-analysis. Pancreas. 2016 Jul 1;45(6):789-95.

71. Bronstein YL, Loyer EM, Kaur H, Choi H, David C, DuBrow RA, et al. Detection of small pancreatic tumors with multiphasic helical CT. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2004 Mar;182(3):619-23.

72. Legmann P, Vignaux O, Dousset B, Baraza AJ, Palazzo L, Dumontier I, et al. Pancreatic tumors: comparison of dual-phase helical CT and endoscopic sonography. AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1998 May;170(5):1315-22.

73. Ichikawa T, Haradome H, Hachiya J, Nitatori T, Ohtomo K, Kinoshita T, et al. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: preoperative assessment with helical CT versus dynamic MR imaging. Radiology. 1997 Mar;202(3):655-62.

74. Wong JC, Lu DS. Staging of pancreatic adenocarcinoma by imaging studies. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2008 Dec 1;6(12):1301-8.

75. Fattahi R, Balci NC, Perman WH, Hsueh EC, Alkaade S, Havlioglu N, et al. Pancreatic diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI): comparison between mass-forming focal pancreatitis (FP), pancreatic cancer (PC), and normal pancreas. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2009 Feb;29(2):350-6.

76. Rijkers AP, Valkema R, Duivenvoorden HJ, Van Eijck CH. Usefulness of F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography to confirm suspected pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. European Journal of Surgical Oncology (EJSO). 2014 Jul 1;40(7):794-804.

77. Choi M, Heilbrun LK, Venkatramanamoorthy R, Lawhorn-Crews JM, Zalupski MM, Shields AF. Using 18F Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) to monitor clinical outcomes in patients treated with neoadjuvant chemo-radiotherapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. American Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010 Jun;33(3).

78. Wang Z, Chen JQ, Liu JL, Qin XG, Huang Y. FDG-PET in diagnosis, staging and prognosis of pancreatic carcinoma: a meta-analysis. World Journal of Gastroenterology: WJG. 2013 Aug 7;19(29):4808.

79. Puli SR, Bechtold ML, Buxbaum JL, Eloubeidi MA. How good is endoscopic ultrasound–guided fine-needle aspiration in diagnosing the correct etiology for a solid pancreatic mass?: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Pancreas. 2013 Jan 1;42(1):20-6.

80. Lambe M, Eloranta S, Wigertz A, Blomqvist P. Pancreatic cancer; reporting and long-term survival in Sweden. Acta Oncologica. 2011 Nov 1;50(8):1220-7.

81. Ries LA, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, Hankey BF, Miller BA, Clegg L, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2000. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. 2003;2.

82. Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Koniaris L, Kaushal S, Abrams RA, et al. Resected adenocarcinoma of the pancreas—616 patients: results, outcomes, and prognostic indicators. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2000 Nov 1;4(6):567-79.

83. Embuscado EE, Laheru D, Ricci F, Yun KJ, de Boom Witzel S, Seigel A, et al. Immortalizing the complexity of cancer metastasis: genetic features of lethal metastatic pancreatic cancer obtained from rapid autopsy. Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2005 May 1;4(5):548-54.

84. Unger K, Mehta KY, Kaur P, Wang Y, Menon SS, Jain SK, et al. Metabolomics based predictive classifier for early detection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2018 May 1;9(33):23078.

85. Canto MI, Harinck F, Hruban RH, Offerhaus GJ, Poley JW, Kamel I, et al. International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening (CAPS) Consortium summit on the management of patients with increased risk for familial pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2013 Mar 1;62(3):339-47.

86. Ulrich CD. Consensus committees of the European Registry of Hereditary Pancreatic Diseases, Midwest Multi-Center Pancreatic Study Group, International Association of Pancreatology. Pancreatic cancer in hereditary pancreatitis: consensus guidelines for prevention, screening and treatment. Pancreatology. 2001;1:416-22.

87. Korsse SE, Harinck F, van Lier MG, Biermann K, Offerhaus GJ, Krak N, et al. Pancreatic cancer risk in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome patients: a large cohort study and implications for surveillance. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2013 Jan 1;50(1):59-64.

88. Ngamruengphong S, and Canto MI. Screening for Pancreatic Cancer. Surg. Clin. North Am. 2016;96(6):1223-1233.

89. Janssen QP, O'reilly EM, Van Eijck CH, Koerkamp BG. Neoadjuvant treatment in patients with resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Frontiers in Oncology. 2020;10:41.

90. Tempero MA. NCCN guidelines updates: pancreatic cancer. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2019 May 1;17(5.5):603-5.

91. Varadhachary GR, Tamm EP, Abbruzzese JL, Xiong HQ, Crane CH, Wang H, et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: definitions, management, and role of preoperative therapy. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2006 Aug 1;13(8):1035-46.

92. Katz MH, Pisters PW, Evans DB, Sun CC, Lee JE, Fleming JB, et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: the importance of this emerging stage of disease. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2008 May 1;206(5):833-46.

93. Callery MP, Chang KJ, Fishman EK, Talamonti MS, Traverso LW, Linehan DC. Pretreatment assessment of resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: expert consensus statement. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2009 Jul 1;16(7):1727-33.

94. Bockhorn M, Uzunoglu FG, Adham M, Imrie C, Milicevic M, Sandberg AA, et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: a consensus statement by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2014 Jun 1;155(6):977-88.

95. Chakraborty S, Singh S. Surgical resection improves survival in pancreatic cancer patients without vascular invasion-a population based study. Annals of Gastroenterology: Quarterly Publication of the Hellenic Society of Gastroenterology. 2013;26(4):346.

96. Demir IE, Jäger C, Schlitter AM, Konukiewitz B, Stecher L, Schorn S, et al. R0 versus R1 resection matters after pancreaticoduodenectomy, and less after distal or total pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer. Annals of Surgery. 2018 Dec 1;268(6):1058-68.

97. Cameron JL, Crist DW, Sitzmann JV, Hruban RH, Boitnott JK, Seidler AJ, et al. Factors influencing survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer. The American Journal of Surgery. 1991 Jan 1;161(1):120-5.

98. Pedrazzoli S, DiCarlo V, Dionigi R, Mosca F, Pederzoli P, Pasquali C, et al. Standard versus extended lymphadenectomy associated with pancreatoduodenectomy in the surgical treatment of adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas: a multicenter, prospective, randomized study. Lymphadenectomy Study Group. Annals of surgery. 1998 Oct;228(4):508.

99. Trede MI, Schwall G, Saeger HD. Survival after pancreatoduodenectomy. 118 consecutive resections without an operative mortality. Annals of Surgery. 1990 Apr;211(4):447.

100. Allison DC, Bose KK, Hruban RH, Piantadosi S, Dooley WC, Boitnott JK, et al. Pancreatic cancer cell DNA content correlates with long-term survival after pancreatoduodenectomy. Annals of Surgery. 1991 Dec;214(6):648.

101. Birk D, Schoenberg MH, Gansauge F, Formentini A, Fortnagel G, Beger HG. Carcinoma of the head of the pancreas arising from the uncinate process. British Journal of Surgery. 1998 Apr 1;85(4):498-501.

102. Birk D and Beger HG. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented. Pancreatic cancer. Munich: Zuckschwerdt; 2001. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK6880/

103. Lu F, Soares KC, He J, Javed AA, Cameron JL, Rezaee N, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy prior to surgical resection for previously explored pancreatic cancer patients is associated with improved survival. Hepatobiliary Surgery and Nutrition. 2017 Jun;6(3):144.

104. Zhan HX, Xu JW, Wu D, Wu ZY, Wang L, Hu SY, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy in pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Cancer Medicine. 2017 Jun;6(6):1201-19.

105. Wolff RA. Adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy in the treatment in pancreatic malignancies: where are we?. Surgical Clinics. 2018 Feb 1;98(1):95-111.

106. Heinrich S. Neoadjuvant therapy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma—real effects or patient selection?. Hepatobiliary Surgery and Nutrition. 2018 Aug;7(4):289.

107. Klaiber U, Leonhardt CS, Strobel O, Tjaden C, Hackert T, Neoptolemos JP. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 2018 Dec 15;403(8):917-32.

108. Mokdad AA, Minter RM, Zhu H, Augustine MM, Porembka MR, Wang SC, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy followed by resection versus upfront resection for resectable pancreatic cancer: a propensity score matched analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017 Feb 10;35(5):515-22.

109. Zhan HX, Xu JW, Wu D, Wu ZY, Wang L, Hu SY, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy in pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Cancer Medicine. 2017 Jun;6(6):1201-19.

110. Golcher H, Brunner TB, Witzigmann H, Marti L, Bechstein WO, Bruns C, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy with gemcitabine/cisplatin and surgery versus immediate surgery in resectable pancreatic cancer. Strahlentherapie und Onkologie. 2015 Jan 1;191(1):7-16.

111. Lee YS, Lee JC, Yang SY, Kim J, Hwang JH. Neoadjuvant therapy versus upfront surgery in resectable pancreatic cancer according to intention-to-treat and per-protocol analysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports. 2019 Oct 30;9(1):1-8.

112. Ren X, Wei X, Ding Y, Qi F, Zhang Y, Hu X, et al. Comparison of neoadjuvant therapy and upfront surgery in resectable pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review. OncoTargets and Therapy. 2019;12:733.

113. Versteijne E, Suker M, Groothuis K, Akkermans-Vogelaar JM, Besselink MG, Bonsing BA, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy versus immediate surgery for resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: Results of the dutch randomized phase III PREOPANC trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020 Jun 1;38(16):1763-73.

114. Tachezy, M., Gebauer, F., Petersen, C., Arnold, D., Trepel, M., Wegscheider, K., et al., 2014. Sequential neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) followed by curative surgery vs. primary surgery alone for resectable, non-metastasized pancreatic adenocarcinoma: NEOPA-a randomized multicenter phase III study (NCT01900327, DRKS00003893, ISRCTN82191749). BMC Cancer, 14(1), p.411.

115. Ettrich TJ, Berger AW, Perkhofer L, Daum S, König A, Dickhut A, et al. Neoadjuvant plus adjuvant or only adjuvant nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for resectable pancreatic cancer-the NEONAX trial (AIO-PAK-0313), a prospective, randomized, controlled, phase II study of the AIO pancreatic cancer group. BMC Cancer. 2018 Dec;18(1):1.

116. Hozaeel W, Pauligk C, Homann N, Luley K, Kraus TW, Trojan J, et al. Randomized multicenter phase II/III study with adjuvant gemcitabine versus neoadjuvant/adjuvant FOLFIRINOX in resectable pancreatic cancer: The NEPAFOX trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015 May 20; 33 (15).

117. Labori KJ, Lassen K, Hoem D, Grønbech JE, Søreide JA, Mortensen K, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus surgery first for resectable pancreatic cancer (Norwegian Pancreatic Cancer Trial-1 (NorPACT-1))–study protocol for a national multicentre randomized controlled trial. BMC Surgery. 2017 Dec;17(1):1-7.

118. Motoi F, Kosuge T, Ueno H, Yamaue H, Satoi S, Sho M, et al. Randomized phase II/III trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and S-1 versus upfront surgery for resectable pancreatic cancer (Prep-02/JSAP05). Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2019 Feb;49(2):190-4.

119. Bonds M, Rocha FG. Contemporary review of borderline resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019 Aug;8(8):1205.

120. Khorana AA, McKernin SE, Berlin J, Hong TS, Maitra A, Moravek C, et al. Potentially curable pancreatic adenocarcinoma: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2019 Aug 10;37(23):2082-8.

121. Oettle H, Neuhaus P, Hochhaus A, Hartmann JT, Gellert K, Ridwelski K, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and long-term outcomes among patients with resected pancreatic cancer: the CONKO-001 randomized trial. Jama. 2013 Oct 9;310(14):1473-81.

122. Neuhaus P, Riess H, Post S, Gellert K, Ridwelski K, Schramm H, et al. CONKO-001: Final results of the randomized, prospective, multicenter phase III trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine versus observation in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (PC). Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008 May 20;26(15_suppl):LBA4504.

123. Neoptolemos JP, Palmer DH, Ghaneh P, Psarelli EE, Valle JW, Halloran CM, et al. Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2017 Mar 11;389(10073):1011-24.

124. Conroy T, Hammel P, Hebbar M, Ben Abdelghani M, Wei AC, Raoul JL, et al. Unicancer GI PRODIGE 24/CCTG PA. 6 trial: A multicenter international randomized phase III trial of adjuvant mFOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine (gem) in patients with resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018 Jun 07;36(18).

125. Conroy T, Hammel P, Hebbar M, Ben Abdelghani M, Wei AC, Raoul JL, et al. FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018 Dec 20;379(25):2395-406.

126. Tempero MA, Reni M, Riess H, Pelzer U, O'Reilly EM, Winter JM, et al. APACT: phase III, multicenter, international, open-label, randomized trial of adjuvant nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine (nab-P/G) vs gemcitabine (G) for surgically resected Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2019 May 26;37(15).

127. Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011 May 12;364(19):1817-25.

128. Ozaka M, Ishii H, Sato T, Ueno M, Ikeda M, Uesugi K, et al. A phase II study of modified FOLFIRINOX for chemotherapy-naive patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2018 Jun 1;81(6):1017-23.

129. Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante J, Moore M, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013 Oct 31;369(18):1691-703.

130. Goldstein D, El Maraghi RH, Hammel P, Heinemann V, Kunzmann V, Sastre Jet al. Updated survival from a randomized phase III trial (MPACT) of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine alone for patients (pts) with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014 Jan 20;32(3).

131. Cho IR, Kang H, Jo JH, Lee HS, Chung MJ, Park JY, et al. FOLFIRINOX vs gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel for treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer: Single-center cohort study. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology. 2020 Feb 15;12(2):182.

132. Williet N, Saint A, Pointet AL, Tougeron D, Pernot S, Pozet A, et al. Folfirinox versus gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel as first-line therapy in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: a comparative propensity score study. Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology. 2019 Sep;12:1756284819878660.

133. Vogl UM, Andalibi H, Klaus A, Vormittag L, Schima W, Heinrich B, et al. Nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine or FOLFIRINOX as first-line treatment in patients with unresectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: does sequence matter?. BMC Cancer. 2019 Dec;19(1):1-8.

134. Watanabe K, Hashimoto Y, Umemoto K, Takahashi H, Sasaki M, Imaoka H, et al. Clinical outcome of modified FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel as first line Chemotherapy in Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017 Mar 21;35(4).